the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center,

the Arhoolie Foundation,

and the UCLA Digital Library

Mid-century Mexico was the hub of the Latin American entertainment industry, a leader in music and film production for the continent. But breaking into that establishment was not easy, especially for an outsider.

Mid-century Mexico was the hub of the Latin American entertainment industry, a leader in music and film production for the continent. But breaking into that establishment was not easy, especially for an outsider.

“Listen, México at that time was an extreme bunker of nationalism,” said Odeon Chile’s artistic director Rubén Nouzeilles, in an interview on a Chilean music website. “Nobody could go there to sing boleros because that was the patrimony of the Mexicans, just as nobody would think of donning a charro hat and go compete with (a mariachi star). Lucho Gatica, apart from being a great artist, was also a conquistador.”

And the conquest was swift. The singer quickly became part of bolero royalty in Mexico. He was soon turning out hit after hit, hosting his own TV show, and making a series of films with Mexico’s biggest stars.

Gatica had his pick of songs by the country’s top composers: “Solamente Una Vez” and “María Bonita” by Agustín Lara; “Un Poco Mas” by Alvaro Carrillo; “La Puerta” by Luis Demetrio; “Nunca” by Guty Cardenas; and the crossover classic “Perfidia” by Alberto Domínguez. But it was with “No Me Platiques Más” by Mexican composer Vicente Garrido that he scored an early hit that would become his signature song. In 1956, he performed the number in the film of the same name, almost whispering the tune into the ear of his lovely co-star, a former Miss Mexico.

Gatica had his pick of songs by the country’s top composers: “Solamente Una Vez” and “María Bonita” by Agustín Lara; “Un Poco Mas” by Alvaro Carrillo; “La Puerta” by Luis Demetrio; “Nunca” by Guty Cardenas; and the crossover classic “Perfidia” by Alberto Domínguez. But it was with “No Me Platiques Más” by Mexican composer Vicente Garrido that he scored an early hit that would become his signature song. In 1956, he performed the number in the film of the same name, almost whispering the tune into the ear of his lovely co-star, a former Miss Mexico.

Gatica had an ear for hits.

He proved this when he first heard a song that would become one of the most beloved boleros of all time, especially among Mexican-Americans. The singer was in Barcelona when, as he recalled in recent interview, he got a call from an associate in Mexico pitching a new song. The caller sang a snippet over the phone, and that was enough for Gatica. He dropped everything on the spot and flew back to Mexico to record Alvaro Carrillo’s unforgettable “Sabor a Mí.”

He could also spot talented new songwriters.

In 1959, Gatica collaborated with an up-and-coming composer from Veracruz named Armando Manzanero. He recorded “Voy a Apagar la Luz” by the 24-year-old, who would become one of Mexico’s most celebrated pop songwriters during the 1960s and ’70s. The two artists also launched a tour of the United States, with Manzanero accompanying Gatica on piano.

Near the end of the decade, Gatica recorded two immortal tunes by Mexico’s Roberto Cantoral, “El Reloj” and “La Barca.” Both songs have since been recorded hundreds of times by such varied artists as Plácido Domingo, Joan Báez, and Linda Ronstadt. Forty years later, however, it was Gatica’s version of those two classics that was inducted into the inaugural Latin Grammy Hall of Fame (2001), along with Santana's "Oye Como Va" (1970) and Antonio Carlos Jobim’s "The Girl From Ipanema" (1963).

Through these peak years, Gatica sustained a touring itinerary that was both hectic and glamorous.

In 1957, he returned to Cuba in an emotional show before 30,000 people at Havana’s Gran Estadio. He wept when he was surprised on stage by his mother, whom he hadn’t seen in years and who had been secretly flown in from Santiago for the occasion. Gatica also played a more intimate venue at the Hotel Nacional’s Cabaret Parisién, accompanied on piano by famed fílin composer Frank Domínguez, who wrote the immortal bolero “Tú Me Acostumbraste.”

As the decade came to a close, Gatica made his first trip to Spain, where he was received like a head of state. Thousands of fans lined the streets of Madrid, carrying flags and homemade welcome signs as the star waved back from his passing convertible. His performances in the Spanish capital during 1959 were, as Omar Martinez wrote in a 2007 essay, “social events which attracted royalty, politicians, movie stars and jet setters from all over Europe.”

Luchomania had gone global. Gatica shared the stage in Paris with Edith Piaff. He performed in Monte Carlo at the invitation of Princess Grace. And he appeared before a massive crowd in the Philippines at the same arena where, years later, boxers Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier would hold the "Thrilla in Manila."

Back in the U.S., Gatica was also making waves in the entertainment industry.

The handsome Chilean hobnobbed with Hollywood celebrities, attending gatherings hosted by the film studio Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. He famously met Elvis Presley at MGM, during a break in the filming of Jailhouse Rock. A photograph from that encounter rocketed around the world, and was frequently mentioned in Gatica’s obituaries six decades later. As the Mexican newspaper Vanguardia recalled: “Here was the King of Rock and the King of the Bolero, one on one, absolute monarchs in their respective genres.”

The handsome Chilean hobnobbed with Hollywood celebrities, attending gatherings hosted by the film studio Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. He famously met Elvis Presley at MGM, during a break in the filming of Jailhouse Rock. A photograph from that encounter rocketed around the world, and was frequently mentioned in Gatica’s obituaries six decades later. As the Mexican newspaper Vanguardia recalled: “Here was the King of Rock and the King of the Bolero, one on one, absolute monarchs in their respective genres.”

Gatica also became a sought-after celebrity guest on American television during the 1950s, appearing on the variety shows of Dinah Shore, Perry Como, Patti Page, and the era’s ultimate entertainment showcase, “The Ed Sullivan Show.” He also recorded for the first time in English with the orchestra of Nelson Riddle, the music director for Frank Sinatra, who had a lifelong friendship with his Chilean counterpart. Though they weren’t hits, recordings from those sessions on Capitol Records, including “Blue Moon” and “Mexicali Rose,” are now prized by record collectors.

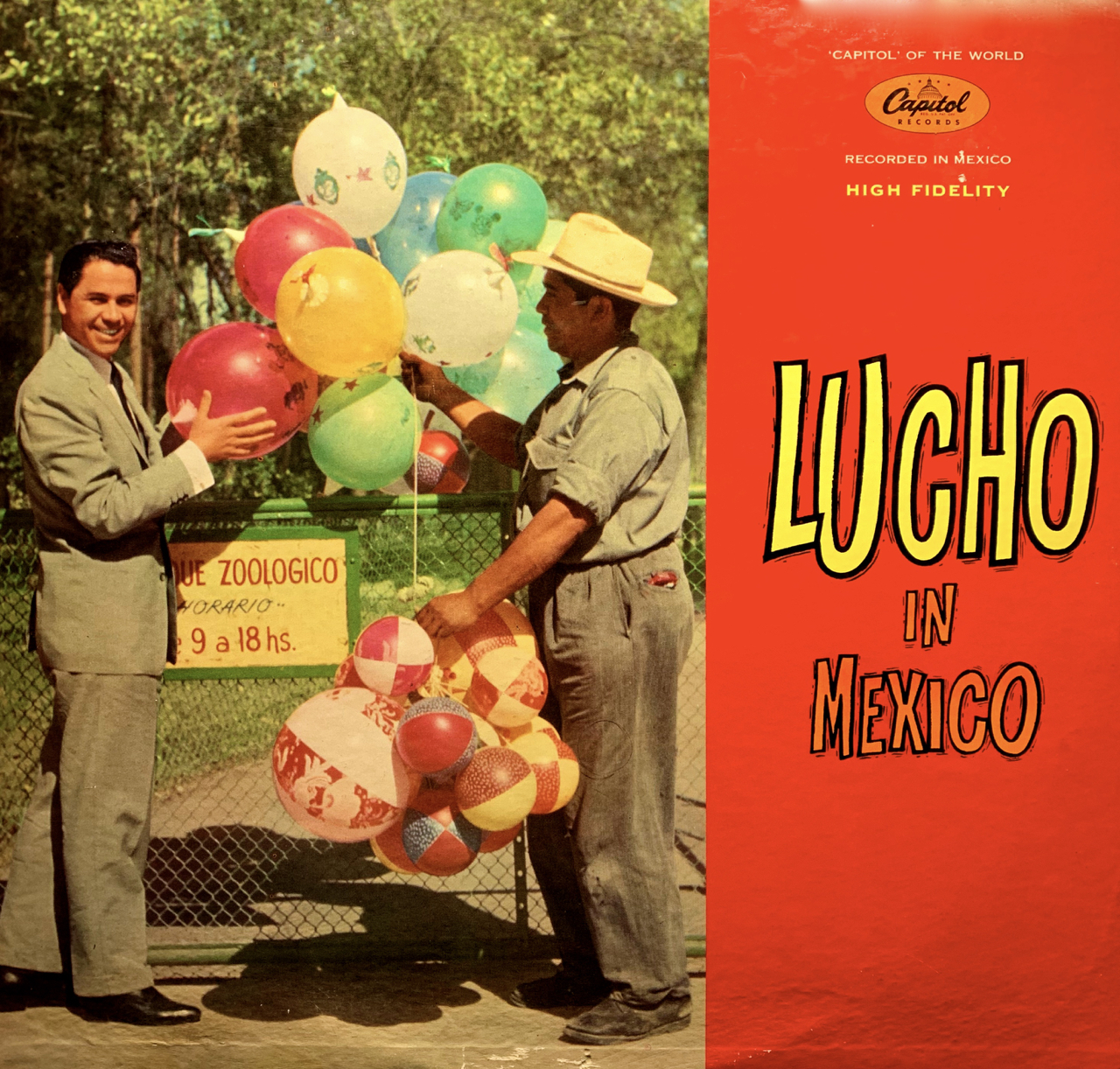

Capitol did much better with reissues of Gatica’s Latin American repertoire, introducing Americans to a golden archive of romantic boleros. Under the label’s “Capitol of the World” series, the company released several Gatica albums in rapid succession, starting in 1956 with South American Songs, a folk collection recorded in Chile. In 1960, Capitol issued Lara by Lucho, with songs by Agustín Lara, recorded in Mexico with the orchestra of frequent collaborator José Sabre Marroquín.

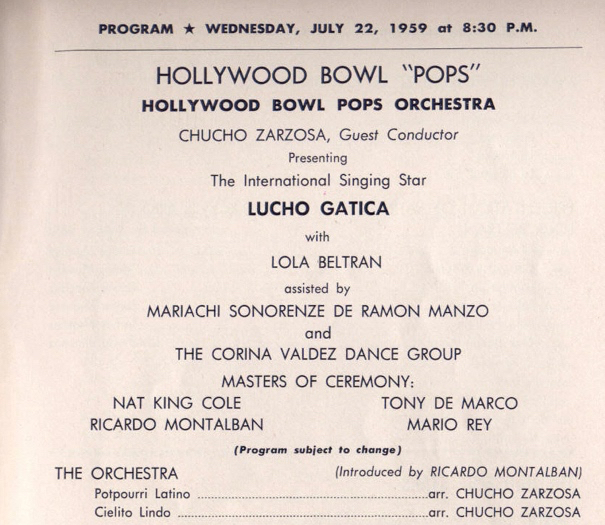

During this same period, Capitol was also hitting it big with a series of Spanish-language albums by popular crooner Nat “King” Cole, who had a friendship with Gatica. The two singers had met earlier in Havana, where Gatica introduced Cole at the fabled Tropicana nightclub. Cole would get the chance to return the gesture on his L.A. home turf, introducing Gatica at the Hollywood Bowl on the night of Wednesday, July 22, 1959.

During this same period, Capitol was also hitting it big with a series of Spanish-language albums by popular crooner Nat “King” Cole, who had a friendship with Gatica. The two singers had met earlier in Havana, where Gatica introduced Cole at the fabled Tropicana nightclub. Cole would get the chance to return the gesture on his L.A. home turf, introducing Gatica at the Hollywood Bowl on the night of Wednesday, July 22, 1959.

The Bowl concert would be followed four years later by another milestone, Gatica’s appearance at Carnegie Hall on April 5, 1963. In what The New York Times called “a bravura performance,” Gatica was backed by a symphony orchestra conducted by Argentina’s Lalo Schifrin. Gatica’s opening night show was broadcast live by radio to his native country.

No matter where he travelled or lived, Gatica always gave credit to Mexico as the launching pad of his career, and the fulfillment of a childhood dream.

“I came to the country that was the temple of the bolero,” he told reporter Marisol García in a 2007 interview for La Nación Domingo. “All the singers who I admired were all in Mexico, during their glory days. The competition was tremendous! Who could ever imagine that, having heard their music in Chile through long-wave radio on “La Voz de América Latina” (broadcast by Mexico’s XEW), I would wind up working with all of these artists.”

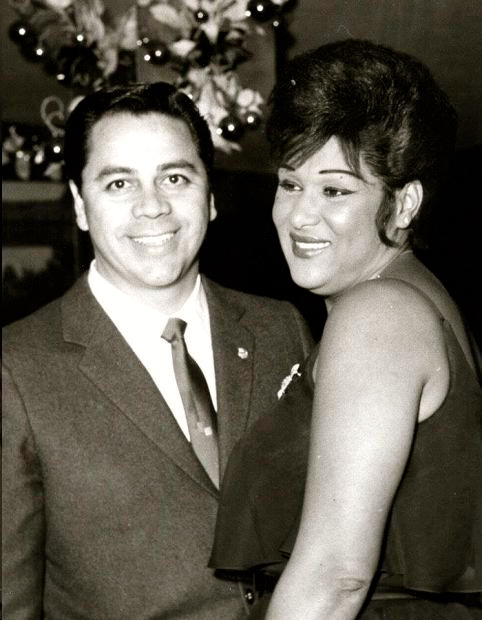

Gatica found more than career success in Mexico. He also found love.

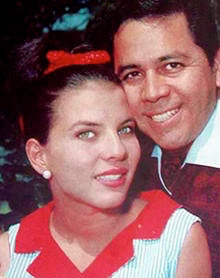

In 1960, he married his first wife, María del Pilar Mercado Cordero, a former Miss Puerto Rico (1957) and popular film actress known as Mapita Cortés. The couple had five children, including first-born Luis, who became a successful actor, and the youngest, Alfredo, a music producer.

After 18 years of marriage, the glamorous celebrity couple divorced.

It was 1978 and Gatica was turning 50. The bolero craze had cooled. The splendor of his seductive tenor had faded. And his recording prospects had dwindled.

It was time to make another change.

The middle-aged singer moved to Los Angeles. Luchomania was a thing of the past, but the aging star would not be forgotten. The last half of his life would bring belated tributes, as well as recognition from a new generation of romantic singers.

The Comeback

By the mid-1980s, an entirely new set of superstars dominated the lucrative Latin field of romantic pop music: Spain’s Julio Iglesias, Venezuela’s Jose Luis Rodriguez, Mexico’s José José, and the United States’s Vikki Carr and Gloria Estefan.

These and a host of other top artists gathered at A&M Studios in Los Angeles in the spring of 1985 to record the Latin version of “We Are the World,” the famous charity song for famine relief written by Michael Jackson and Lionel Richie. The Spanish version, "Cantaré, Cantarás," also became a pop music phenomenon, covered prominently in the Los Angeles Times. Gatica was also part of the all-star ensemble, but during the recording, he was positioned in the top row, at the rear, just another member of the chorus.

From his remote perch, Gatica watched as younger balladeers took the spotlight. The Chilean singer, who once caused near-riots by his very presence, was hardly noticed at the event that day. The pecking order in the studio was a symbol of how far his star had fallen. And it begged the question: Would he have even been invited if the record had not been co-produced by his nephew, Humberto Gatica, who by then was a top engineer with clients of the caliber of Michael Jackson, Tina Turner, and Barbra Streisand?

Not everybody relegated Gatica to the back burner in his later years. In May 1990, he made a triumphant return to Madrid, after a 10-year absence. His legacy had received a boost from celebrated Spanish filmmaker Pedro Almodóvar, who had used Gatica’s song “Encadenados” in the soundtrack to his 1983 film Entre Tinieblas.

The Chilean singer, at age 62, returned to Florida Park, the venue where he had debuted three decades earlier. The place was buzzing with the capital’s glitterati, who came to see him, and to be seen.

“From the moment Lucho began to sing, everybody became lovers,” wrote critic Maruja Torres in El País. “They applauded the man who proved that with time, wisdom flawlessly replaces power. He doesn’t sing like he did before, nor does he try. Instead, it was like he revisited each song from the perspective that irony and maturity provide.”

It was a fitting start for a decade that would see the resurgence of the old boleros Gatica had popularized. The genre’s ’90s revival was propelled by a series of fabulously successful albums by young Mexican singing idol Luis Miguel, introducing a new generation of fans to the classic pop music of their parents and grandparents.

The trend also brought new audiences to Gatica. In 1995, at the apex of his bolero phase, Luis Miguel invited Gatica on stage at the former Universal Amphitheatre in Los Angeles, greeting his aging predecessor with a hug and a kiss on the cheek. The following year, Luis Miguel joined a constellation of top stars in a televised tribute to Gatica, produced by HBO, at Miami’s James L. Knight Center. The two-hour special featured Gatica in duets with Juan Gabriel, José José, Julio Iglesias, and his old friend from Cuba, Olga Guillot.

By the end of the century, the King of the Bolero had been enthroned anew, this time as “elder statesman” of the romantic musical tradition of Latin America.

The Swan Song

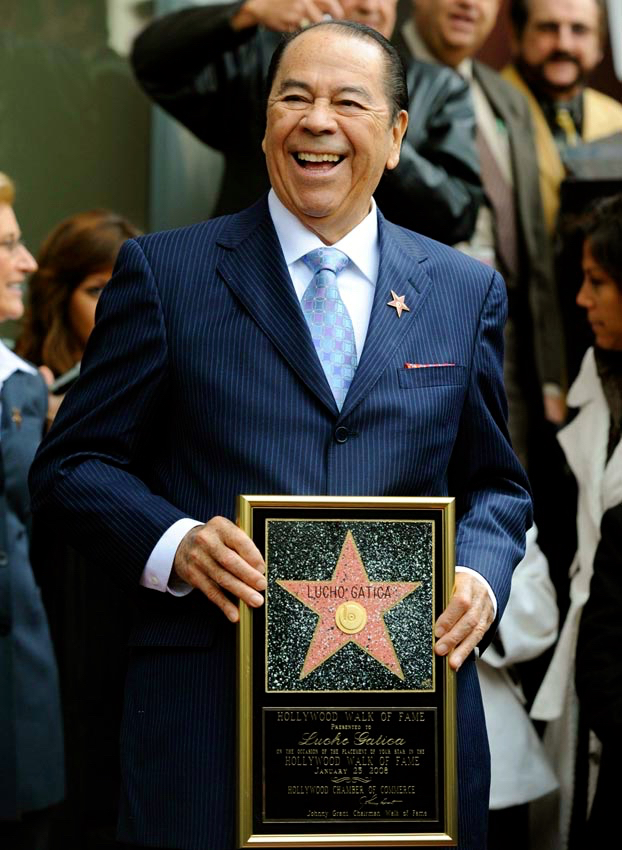

Gatica went on to receive more major honors in the new millennium. In 2008, the year he turned 70, he became one of only two Chileans (the other being TV host Don Francisco) to receive a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Later that year, the Latin Recording Academy honored him with a trophy for lifetime achievement.

Gatica went on to receive more major honors in the new millennium. In 2008, the year he turned 70, he became one of only two Chileans (the other being TV host Don Francisco) to receive a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Later that year, the Latin Recording Academy honored him with a trophy for lifetime achievement.

For Gatica, however, one important thing was still missing: the full appreciation of his fellow countrymen. Many Chileans felt ambivalent about his international success, which had required him to live most of his life away from home. “Gatica will be remembered in the country as the lost son, who died a faraway hero,” declared Chile Today in its English-language obituary.

Nevertheless, Gatica received multiple national honors from the Chilean government and arts community: Gaviota de Oro at Chile’s famed the song festival at Viña del Mar (1992); Medalla de Oro from Chile’s author’s rights society, Sociedad Chilena de Derechos de Autor, bestowed personally by Chilean President Michelle Bachelet (2007); Orden al Mérito Artístico y Cultural Pablo Neruda, named for the famed Nobel laureate (2012).

Gatica received his country’ highest cultural award in 2002, on the 50th anniversary of his professional career. He was awarded the Orden al Mérito Gabriela Mistral, joining previous recipients that included Paul McCartney.

In acknowledging the honor, Gatica paid tribute to his brother, who had died in 1996. “I would have wanted my brother Arturo to be here too,” he said, “because he was to blame for me being an artist who has given a measure of renown to my country.”

The following year, at age 75, Gatica collaborated with Chilean hip-hop stars Ana Tijoux and Víctor Flores on “Me Importas Tú,” a contemporary reimagining of his old bolero, “Piel Canela,” on which Gatica sticks to reciting rather than singing the original lyric.

Gatica made his final recording in 2013, at age 85. Titled “Historia de Un Amor,” the work was once again co-produced by his nephew, Humberto Gatica. It featured duets with a host of contemporary singers, including Luis Fonsi, Laura Pausini, Michael Bublé, Nelly Furtado, and Beto Cuevas of the Chilean rock band La Ley.

The singer’s attempt to find renewed relevance fell flat. Even so, he was content in his later years, as he would tell reporters, because he had led a full life.

Ever the romantic, Gatica married twice after his initial divorce, and had two more daughters, one by each wife. In 1986, the year he turned 58, he wed his third and final wife, Leslie Deeb, who gave birth to his seventh and final child. Both of his youngest daughters, Luchana (goddaughter of Julio Iglesias) and Lily Teresa, are in show business in the Unites States.

The singer celebrated his 90th birthday this year in Mexico City, three months before he died. One news report described a sad picture of the artist in his final days, suffering from diabetes and diminishing mental capabilities, playing records and spending hours singing at home by himself.

Yet, photos from his birthday celebration show him smiling broadly, surrounded by his eleven grandchildren. The youngsters had prepared a surprise gift: a recording of his famous boleros, in their own voices.

That same day, civic leaders in his hometown unveiled a 6-foot bronze statue depicting the Gatica brothers as they had started, Lucho singing into a mic and Arturo playing guitar. Gatica himself was well aware of his artistic legacy, which he once succinctly summarized for a magazine reporter.

That same day, civic leaders in his hometown unveiled a 6-foot bronze statue depicting the Gatica brothers as they had started, Lucho singing into a mic and Arturo playing guitar. Gatica himself was well aware of his artistic legacy, which he once succinctly summarized for a magazine reporter.

"As long as people fall in love,” he said, “my songs will be popular."

– Agustín Gurza

Read Artist Biography: Lucho Gatica, Rey del Bolero, Part 1.

0 Comments

Stay informed on our latest news!

Add your comment