The Legacy of a Music Lover: Six Decades of Collecting Records and Preserving Culture

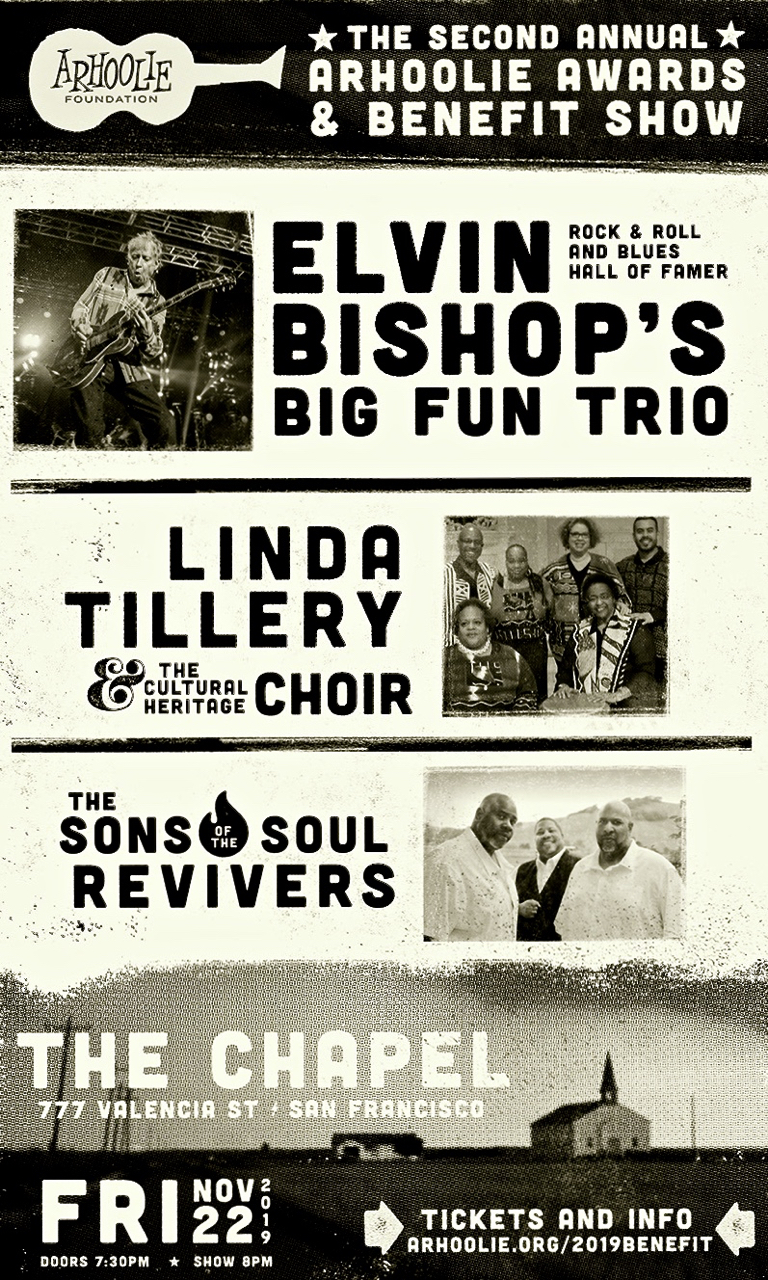

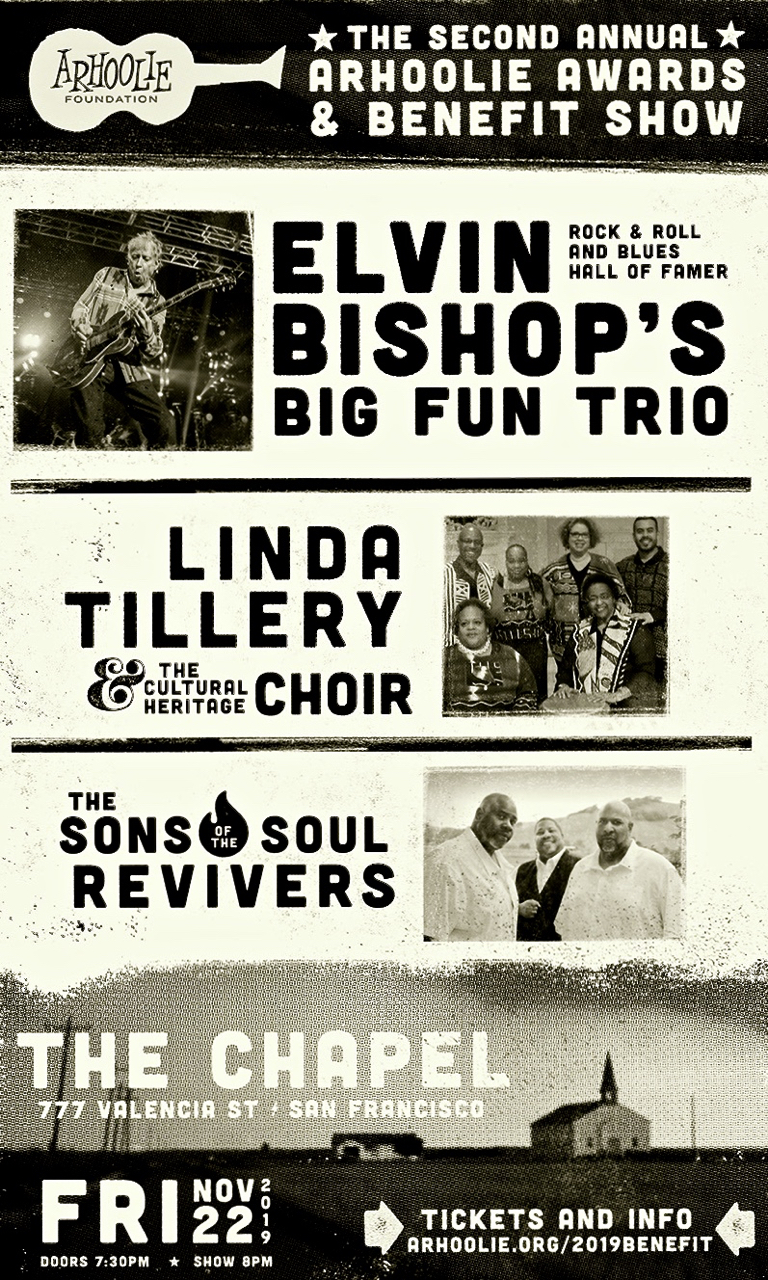

There was a warm, cheerful spirit this past November in a San Francisco club called The Chapel during the Second Annual Arhoolie Awards and Benefit Concert, a spirit that was instantly enveloping. I had never attended one of the celebrated events sponsored by the roots-music organization, but I felt immediately at home.

There was a warm, cheerful spirit this past November in a San Francisco club called The Chapel during the Second Annual Arhoolie Awards and Benefit Concert, a spirit that was instantly enveloping. I had never attended one of the celebrated events sponsored by the roots-music organization, but I felt immediately at home.

People didn’t put on a pretense of being cool. They didn’t have that forbidding vibe of being the in-crowd. They were simply enjoying themselves and digging the rollicking blues and gospel performers on stage. The crowd’s shared cultural affinity made it feel like a communal happening.

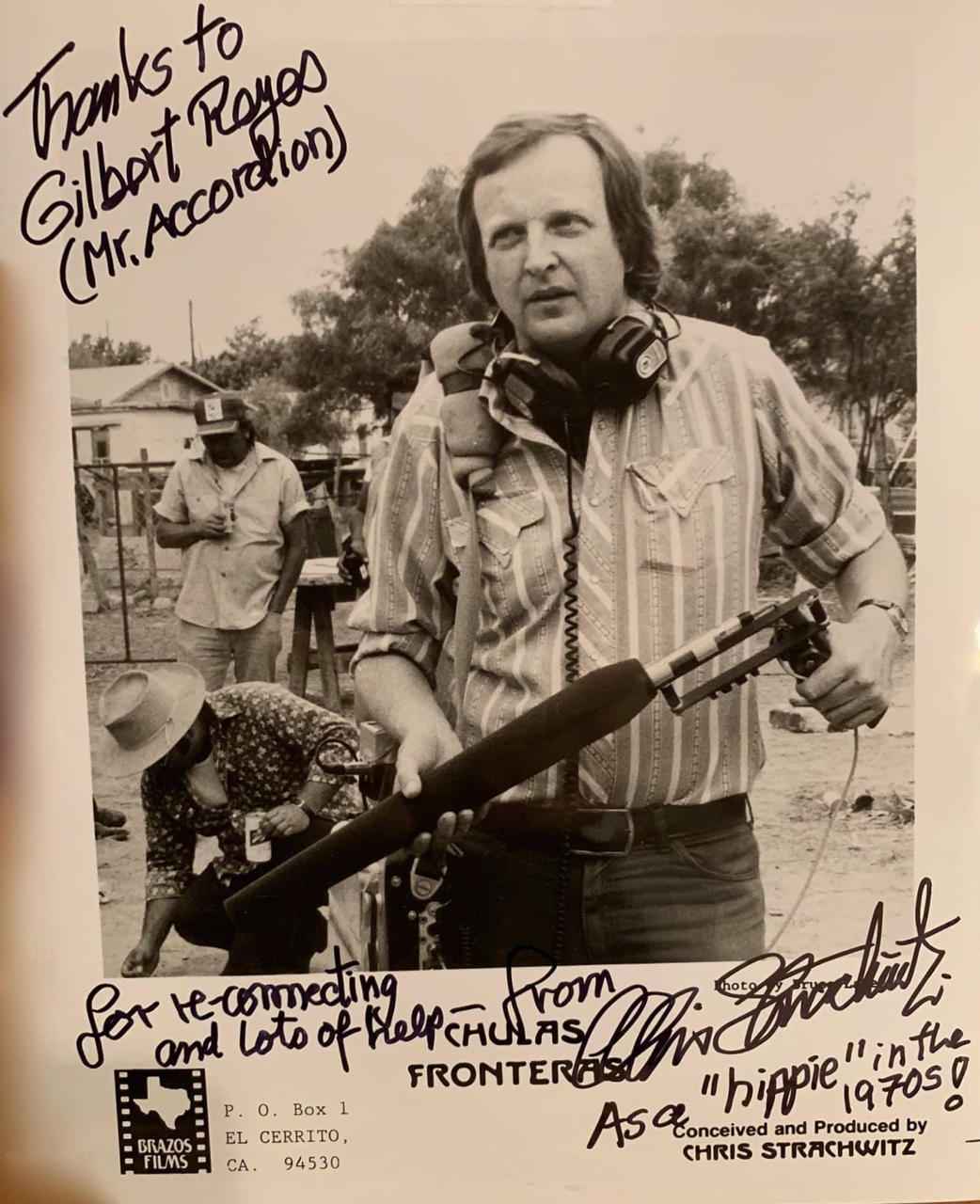

For those unfamiliar with the history of Arhoolie, the revered musical brand created by record collector and producer Chris Strachwitz, the title of last month’s event might be a bit misleading. Yes, it was only the second annual benefit concert for the non-profit Arhoolie Foundation, a leading sponsor of the Frontera Collection hosted online at UCLA. But the enterprise has been around a lot longer than that.

Next year, in fact, will mark the 60th anniversary of Arhoolie Records, the label Strachwitz started on a shoestring and built into an essential archive of American grass-roots musical styles, including blues, jazz, folk, zydeco, bluegrass, and Mexican genres popular along the U.S.-Mexico border, especially norteño, conjunto, and Tejano.

The benefit featured awards for Bay Area musicians, including Elvin Bishop, the veteran blues guitarist who received the Chris Strachwitz Legacy Award. But when Strachwitz came out on stage to present the honors, with his unassuming but confident demeanor, the cheers of adoring fans left no doubt who they considered the main act.

Veteran Bay Area writer and deejay Jesse “Chuy” Varela, who emceed the event, underscored Strachwitz’s stature with a glowing introduction in booming announcer tones. Later in an interview, Varela shed some light on the appeal of a man he calls “my uncle Chris.”

“Chris created a community, bro, of people his age who… hey man, they followed him,” said Varela, a longtime Arhoolie collaborator and frequent customer at Down Home Music, the record shop Strachwitz opened in 1976 in El Cerrito, north of Berkeley “Just hanging around the store you're amazed at all the famous musicians that come rolling through because of the reputation that it has, musicians who are digging for inspiration or looking for music they want to research.”

Varela ticks off the names of local artists from the 1960s who were denizens of Down Home before they were famous: “Tom Fogerty and all the Creedence guys hung around; Country Joe McDonald went through there. And then you had the guys who moved out here and kind of made it their second home, like Taj Mahal and Charlie Musselwhite. And later, Billie Joe Armstrong from Green Day, man, those kids went through there.”

That mingling of music-lovers and music-makers formed bonds that lasted.

“Dude, it’s a lot of love, man,” says Varela. “All it takes is going to an Arhoolie party or hanging out at Down Home like on a Saturday afternoon, just to see it.”

That captures what I experienced at the concert, held in the Mission District, the gentrified neighborhood that was once a hotbed of Latino grassroots activism in politics and the arts. I looked around the venue and saw a lot of contemporaries, gray-haired Baby Boomers including some who are now key benefactors of the Arhoolie Foundation. As soon as I walked in, I ran into Jonathan Clark, the mariachi musician and historian who contributed a chapter to my book on the Frontera Collection. We soon became a trio when joined by Tom Diamant, a board member of the Arhoolie Foundation and Strachwitz’s longtime partner.

That captures what I experienced at the concert, held in the Mission District, the gentrified neighborhood that was once a hotbed of Latino grassroots activism in politics and the arts. I looked around the venue and saw a lot of contemporaries, gray-haired Baby Boomers including some who are now key benefactors of the Arhoolie Foundation. As soon as I walked in, I ran into Jonathan Clark, the mariachi musician and historian who contributed a chapter to my book on the Frontera Collection. We soon became a trio when joined by Tom Diamant, a board member of the Arhoolie Foundation and Strachwitz’s longtime partner.

It all brought back the spirit of the ’60s, when I was a student at Berkeley and Chris was building his music business. It was a pre-digital time when pop songs provided the social glue that brought people together and expressed common community values – for peace, love, and justice; against war, poverty and racism.

In light of the current generational antagonism that blames Boomers for causing all manner of social ills, from crushing student debt to global warming, it was reassuring to experience a positive manifestation of that generation’s lofty ideals.

The joyful evening provided a moment to reflect on the tremendous accomplishments of Strachwitz and Arhoolie, built disc by disc over six decades. He started by gathering and preserving the recorded ethnic music of the working classes, which others considered worthless. In discarded stockpiles of unwanted records, Strachwitz saw musical treasures, like a miner panning for gold in muddy waters.

Culturally speaking, his major contribution came in giving that music its proper place and respect. That approach was especially important in the case of Mexican folk and country music, which was scorned even by many Mexicans. Strachwitz made no distinction between genres on either side of the cultural gap. So he collected and produced Mexican music on a par with American roots styles, unencumbered by the prejudices of puzzled people who would scratch their heads and wonder, “What do you want that stuff for?”

In the early years, Arhoolie’s mission synced seamlessly with the era’s desire for authenticity and rejection of commercial artifice. Strachwitz came up at a time when young people were searching out roots music for themselves, sparking revivals in folk, blues, and ethnic music of all types.

This tall, lanky immigrant found himself in the right place at the right time.

Strachwitz came to this country as a teenager from an upper-crust German family, seeking a safe haven in the aftermath of WWII. He arrived with a thirst for music other than the folk music of his European homeland, which he found contrived and unfeeling. His listening capacity was wide open.

“He's a music lover, and he came here at a time when there was really rich music happening,” says Varela, who worked during the ’80s and ’90s at KPFA-FM, the Berkeley-based Pacifica station where Strachwitz also hosted a long-running program. “He was always very much into learning from people, and hearing things.”

Strachwitz listened and learned, even when he didn’t understand the language musicians were speaking. He didn’t speak Spanish, but responded viscerally to the Mexican regional music of poor, working-class people along the border, with its exquisite vocal harmonies, lively accordions, and peppy polka rhythms.

Strachwitz listened and learned, even when he didn’t understand the language musicians were speaking. He didn’t speak Spanish, but responded viscerally to the Mexican regional music of poor, working-class people along the border, with its exquisite vocal harmonies, lively accordions, and peppy polka rhythms.

“I was always that weird gringo, listening to corridos and banda because I loved what they had to say,” said Strachwitz in an interview last year with El Tecolote, a bilingual newspaper launched in 1970 at San Francisco State as part of a La Raza Studies class. “Mexicans had a very profound way of disclosing their life experiences.”

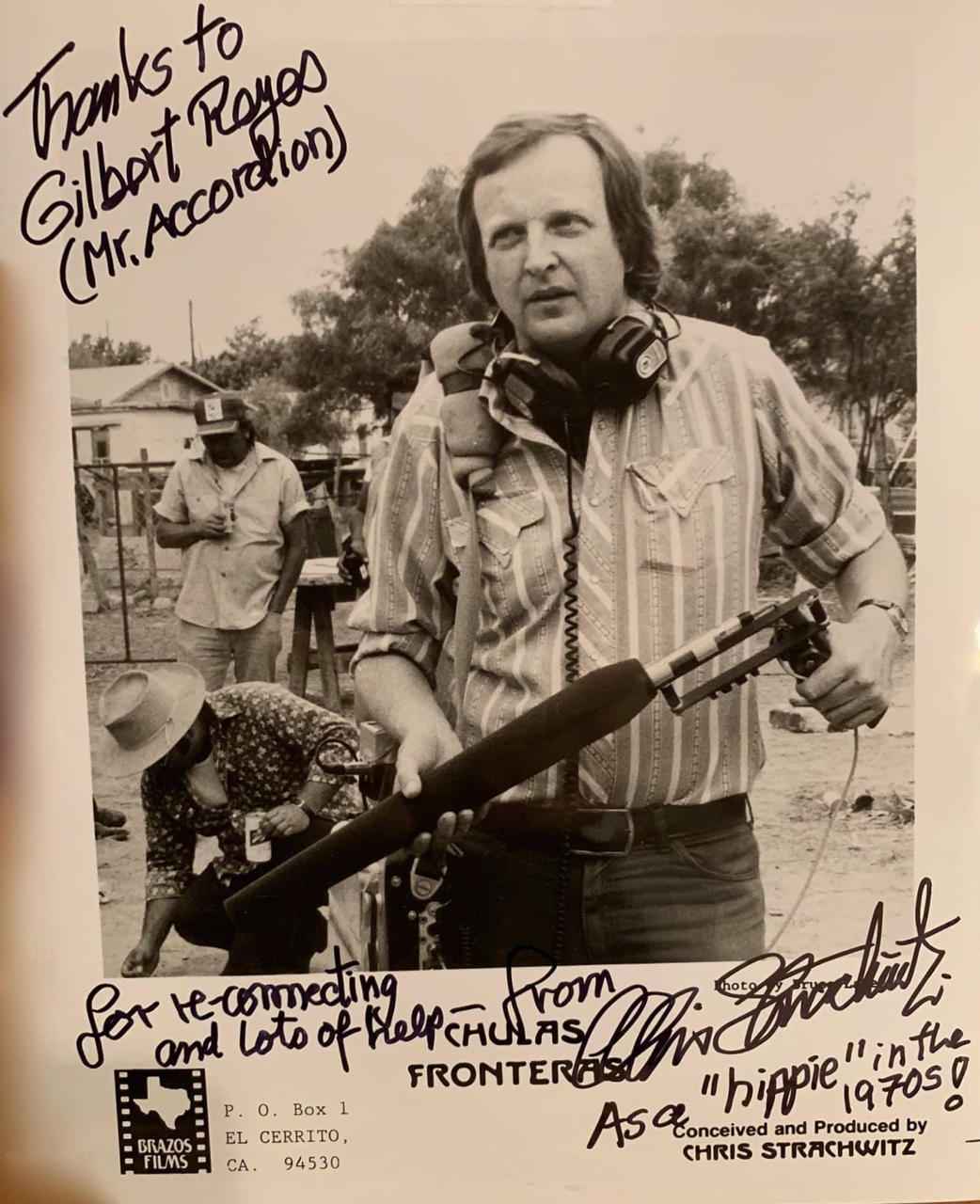

Chris was an explorer, but not an exploiter. He was interested in preservation, not profit. He dove into the nomadic culture of migrant workers and, like them, he was always on the move. He searched out norteño and conjunto artists, befriended them, recorded them, wrote liner notes for their albums, and featured them in his documentary films.

Through that anthropological effort, he taught young Mexican Americans not to discriminate against their own music.

“We were low-riders,” recalls Varela, 65, who attended high school in Martinez, a historic oil town in the East Bay. “We were cholos, and we looked down on Mexican music. But as time went along, we began to realize you can’t cut off that root.”

That’s when the art of record collecting synergized with Chicano activism.

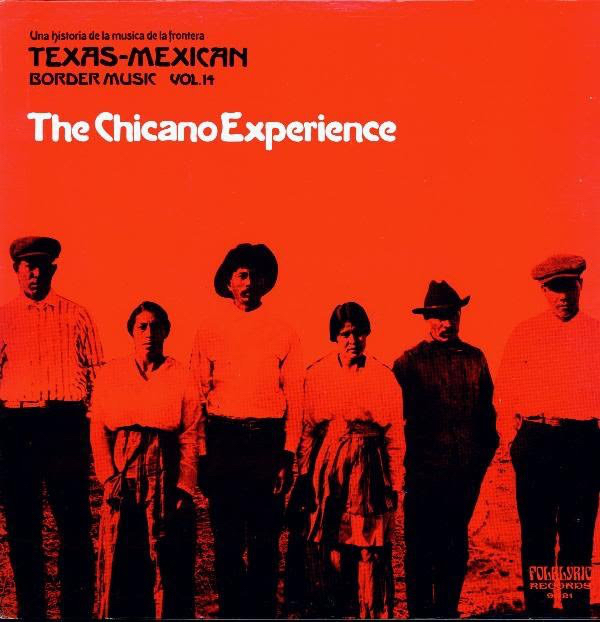

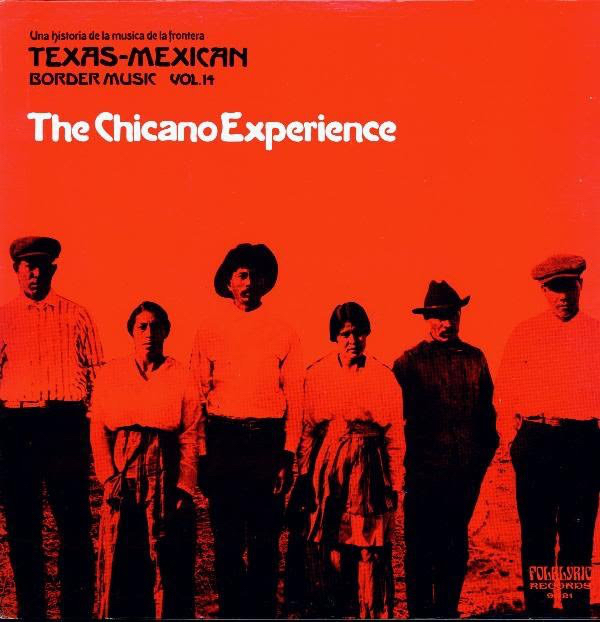

“I was a young Chicano in MEChA (Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán),” continued Varela, who studied music and mass communications at Cal State Hayward, south of Berkeley. “We were kids getting involved with César Chávez and all this stuff, and we discovered the album The Chicano Experience (Texas-Mexican Border Music Vol. 14, Arhoolie Records, 1978). That album became kind of like our manifesto.”

During the phone interview, Varela suddenly breaks out into song with a muted shout: “Soy Chicano, ‘cuz I’m brown and I’m proud.” It’s a line he remembers from another Arhoolie release, Corridos of the Chicano Movement, by the late Rumel Fuentes, a Chicano activist and songwriter from Eagle Pass, Texas.

“We used to sing that like it was our anthem,” Varela continued, the excited memory still animating his voice. “We knew this had a lot of corazón, but it also had a lot of political fire to it as well.”

For Strachwitz – and others like Ry Cooder who collaborated with Flaco Jimenez, the renowned accordionist from San Antonio – being outsiders looking in on Latino culture proved to be an advantage.

“The irony is that it took guys who were not Mexicans who fell in love with this music, and really knew the wealth and depth of it,” says Varela. “As a result, it kind of brought it all back full circle, back to the people who said, ‘Oh yeah, maybe we need to go back and re-examine this.’ ”

Other white figures delving into ethnic music have been accused of cultural appropriation, including Paul Simon with his South African foray. I don’t think Strachwitz can be faulted for that because he always tries to keep the spotlight on the music itself, in its purest, most natural form. I have previously argued, at the risk of portraying Strachwitz as a white savior, that his obsessive record-hunting helped rescue a large chunk of our musical culture from oblivion. Without the Frontera Collection, much of its music would be long forgotten.

But Varela doesn’t quite see it that way.

“No, what I think he did is that he opened it up to the outside world,” says Varela. “One of things about Mexican folks, bro, they never get rid of their records. You can go to any Mexican home and there’s gonna be a little stack of records, and they pass them on. It's like that; it's insular. What Chris helped to do is to open it up, so that outside societies could have a look into what we do. And I think that's something he deserves a lot of credit for.”

Which brings me to my final thought as I surveyed the aging audience at the Arhoolie concert. What will become of this cultural movement once this generation passes on? Who will carry the torch of historic preservation into the future?

The 1960s are history. Tastes changed, and people moved on. Technology blew to bits the very concept of collecting records, with songs now instantly accessible as discreet files, untethered to the release of an album.

As Strachwitz puts it simply: “Records are no longer really an item.”

You can think of Strachwitz as a musical curator, who selects the records he likes and presents them for others to appreciate. Today, however, the role of cultural gatekeeper has gone the way of the LP, Top 40 radio, and the record label A&R guy. Now, people are awash in an avalanche of available music, with nobody to help them sort through it.

“It’s like a total tower of babel out there,” says Strachwitz. “In the old days you had good deejays, good reviewers in newspapers and magazines. There’s so much stuff out there, and young people really do need guidance.”

“It’s like a total tower of babel out there,” says Strachwitz. “In the old days you had good deejays, good reviewers in newspapers and magazines. There’s so much stuff out there, and young people really do need guidance.”

Despite the changes and the challenges, Strachwitz casually deflects a question about his legacy with a soft-spoken response: “I’m really not all that concerned.”

Perhaps his mind rests easy because he’s been carefully planning for the future over the past 20 years. In 2016, Arhoolie Records, with its catalog of some 650 albums, was sold to Smithsonian Folkways Recordings, the nonprofit label of the Smithsonian Institution, the national museum of the United States. Meanwhile, Arhoolie has undertaken the Herculean task of digitizing some 160,000 tracks from the Strachwitz collection of Mexican, Mexican-American, Spanish, Caribbean, and Latin American music, creating the digital archive that comprises the Frontera Collection at UCLA.

Through Frontera and Folkways, this record trove will be available as a resource worldwide for generations to come, delighting music lovers and informing ethnomusicologists.

That is legacy enough for one man.

– Agustín Gurza

Tags

Images