the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center,

the Arhoolie Foundation,

and the UCLA Digital Library

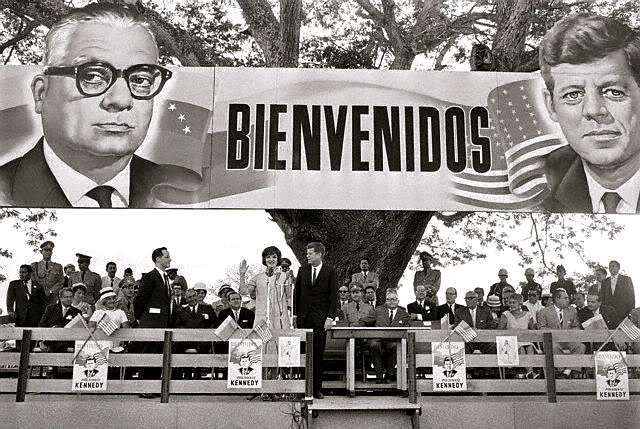

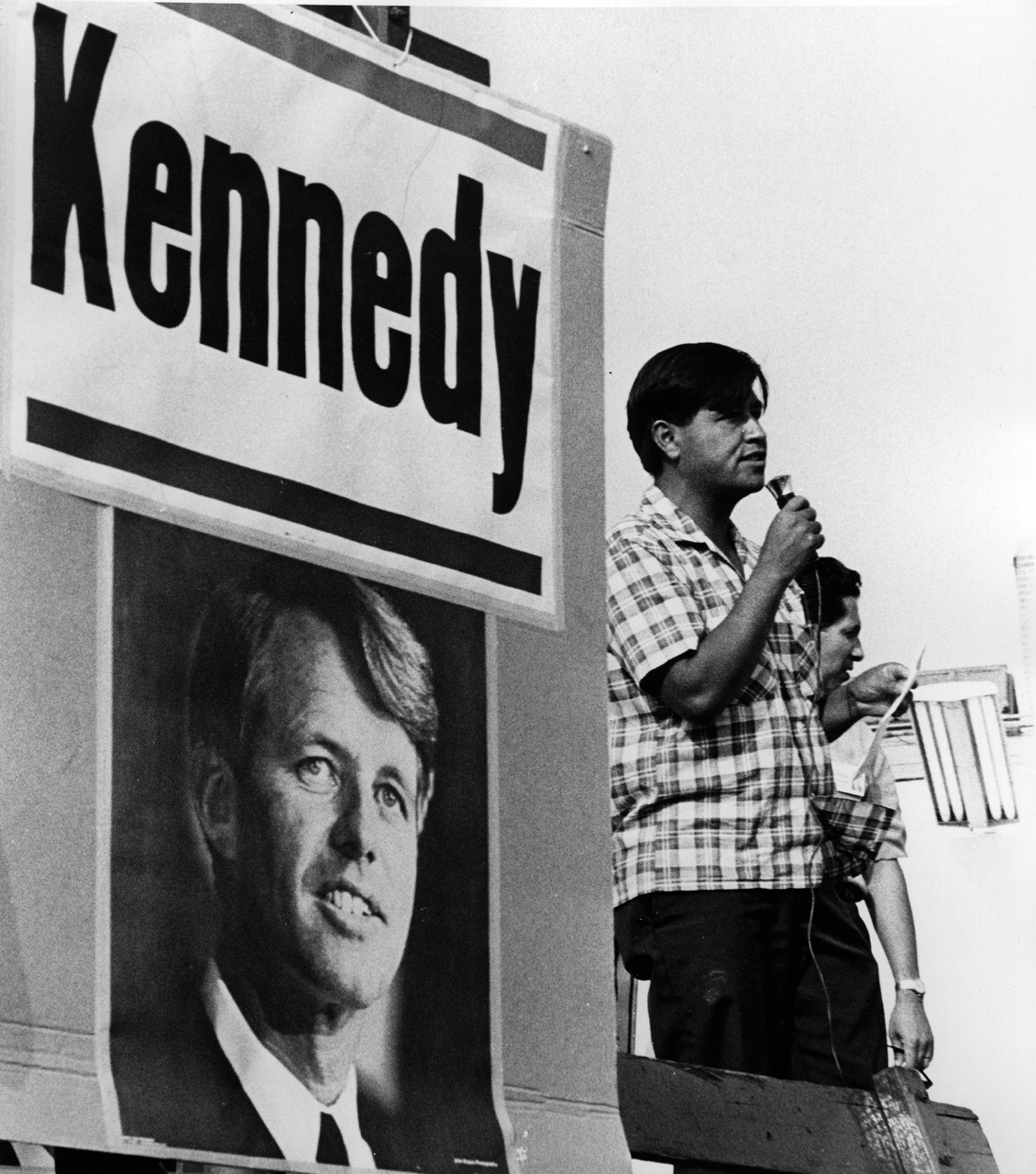

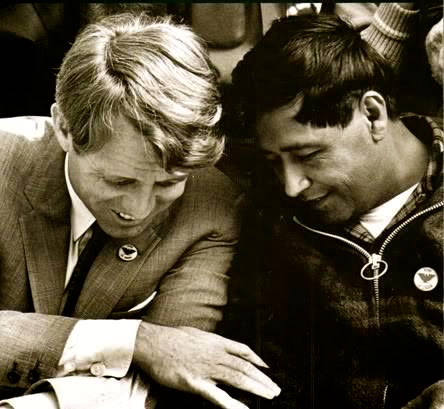

This month marks the 50th anniversary of the assassination of Senator Robert F. Kennedy. The slain presidential candidate was especially admired by the Mexican-American community, as was his martyred brother before him, President John F. Kennedy. That admiration was expressed poetically and emotionally in many songs written as tributes to the fallen leaders.

Most of those songs were written spontaneously immediately following the assassinations, which took place five years apart; first the president in Dallas, followed by the killing in Los Angeles of the senator, his younger brother and former U.S. Attorney General. Many of the compositions were crafted in the traditional style of Mexican corridos, or narrative ballads that recount historical events in a quasi-journalistic fashion, specifying time, place and other historical facts. But these songs – which have become known collectively as “the Kennedy Corridos” – also express in passionate terms the powerful cultural affinity that Mexican-Americans felt for the Kennedys, and the deep sense of loss the community experienced when they were taken so young and at the peak of their political careers.

Most of those songs were written spontaneously immediately following the assassinations, which took place five years apart; first the president in Dallas, followed by the killing in Los Angeles of the senator, his younger brother and former U.S. Attorney General. Many of the compositions were crafted in the traditional style of Mexican corridos, or narrative ballads that recount historical events in a quasi-journalistic fashion, specifying time, place and other historical facts. But these songs – which have become known collectively as “the Kennedy Corridos” – also express in passionate terms the powerful cultural affinity that Mexican-Americans felt for the Kennedys, and the deep sense of loss the community experienced when they were taken so young and at the peak of their political careers.

The Frontera Collection contains an ample sample of corridos written for both John and Robert Kennedy, although it’s by no means definitive. The archive has a much more comprehensive collection of older corridos on 78s, representing the golden era of the recorded genre during the first half of the 20th century. Previously, I gave a detailed analysis of the corrido and its history in a four-part post, starting with the definition of the genre and its traditional elements, such as the role of a narrator, the establishment of time and place, and the farewell verse.

The Kennedy Corridos come much later in time, obviously, during the 1960s and early 1970s. They are all on modern recording formats, mostly 45-rpm singles, as well as 33-rpm albums. And they do not strictly follow established corrido conventions; in fact, a few are not corridos at all, but rather tribute songs in other styles.

The Kennedy Corridos emerged at a time when the genre itself had begun to wane. The commercially recorded corridos of the mid-1900s often lacked the integrity and purpose of their predecessors. In the words of respected corrido expert Américo Paredes, “the corrido in the hands of professional imitators had become self-conscious and fake.”

The Kennedy Corridos emerged at a time when the genre itself had begun to wane. The commercially recorded corridos of the mid-1900s often lacked the integrity and purpose of their predecessors. In the words of respected corrido expert Américo Paredes, “the corrido in the hands of professional imitators had become self-conscious and fake.”

Songwriters no longer championed the epic heroes of the original border corridos, those larger-than-life folk figures locked in life-and-death cultural conflicts, whose stories were kept alive via this oral tradition with ancient roots. They also lacked the urgency of early recorded corridos that served as audio newspapers, recounting events for poor people who had no other access to media.

So, by the 1960s, the corrido was in a slump. Nobody needed ballads any longer to get the news. And the stories the songs used to tell – about the oppressed border hero fighting the dominant Anglo culture – had become like old tales about the Wild West. By the 1960s, most of the Mexican-American population had moved from rural to urban settings, fighting for social equality and going off to Vietnam to fight alongside their fellow American soldiers.

The Kennedy Corridos began to change all that.

“Not until the Kennedy assassination did Texas-Mexican corridos have a subject that would reinvigorate the genre,” writes ethnomusicologist Dan W. Dickey in a section about the corrido in the The Handbook of Texas Music. “During the months following John Kennedy's death, dozens of Kennedy corridos were composed, recorded, and broadcast on Spanish language radio stations in Texas and across the Southwest.”

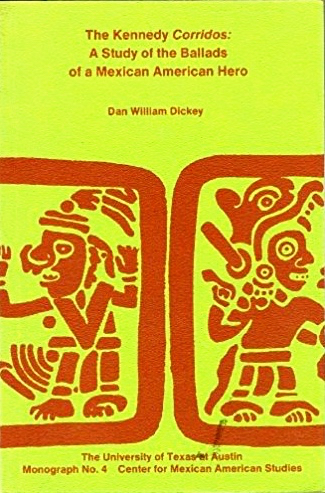

The intrinsic tragedy of the Kennedy stories – charismatic young leaders, champions of civil rights, defenders of the underdog, victims of violence in their prime - was the very stuff of corrido legends. They were an inspiration for young corridistas, who suddenly found new heroes to herald, as Dickey explains in his 1978 book, The Kennedy Corridos: A Study of the Ballads of a Mexican American Hero.

“The corridos and songs about John Kennedy, written and recorded in and around 1963, were an exception to the entertaining, commercially recorded corridos of the time,” writes Dickey. “Instead of being trite or vulgar ballads about local barroom shootings, the corridos about Kennedy in many cases show, in their character, a return to the older corrido of an epic-heroic cast. They are the heartfelt expression or sentiment of Mexican-Americans who saw their own struggles in Kennedy’s, and who were uplifted and inspired by his ideals.”

“The corridos and songs about John Kennedy, written and recorded in and around 1963, were an exception to the entertaining, commercially recorded corridos of the time,” writes Dickey. “Instead of being trite or vulgar ballads about local barroom shootings, the corridos about Kennedy in many cases show, in their character, a return to the older corrido of an epic-heroic cast. They are the heartfelt expression or sentiment of Mexican-Americans who saw their own struggles in Kennedy’s, and who were uplifted and inspired by his ideals.”

Dickey’s book was originally written as his master’s thesis at the University of Texas at Austin, where he studied folklore and ethnomusicology. The expanded work was partly funded by the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library in Boston, according to a review by famed ethnomusicologist Philip Sonnichsen, published in Western Folklore in July of 1981. Sonnichsen praised Dickey’s book, calling it “one of which Américo Paredes can be proud.”

The book covers only those corridos written about President Kennedy, in the immediate aftermath of his assassination on November 22, 1963. But his analysis applies equally to the corridos written five years later after the death of Sen. Robert F. Kennedy, who was shot June 5, 1968 in Los Angeles, after winning the California presidential primary.

Dickey identifies three themes common to the JFK corridos he studied:

First, the elder Kennedy is hailed as a “champion of equal rights,” compared to even the likes of Abraham Lincoln and Jesus Christ.

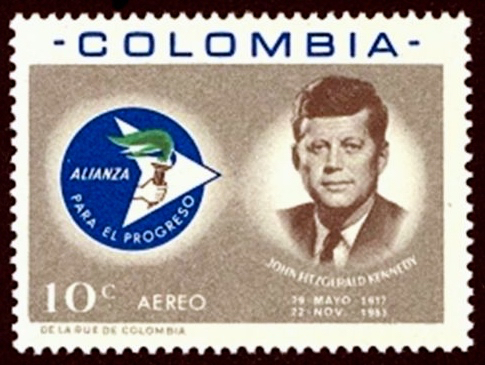

Second, he is hailed as a friend of Mexico and Latin America, a man who made speeches in Spanish, launched the Alliance for Progress to aid the continent, and returned to Mexico a parcel of disputed land on the Texas border called El Chamizal.

Third, he is lionized as a hero and martyr who gave his life for his country, and who struggled for acceptance as a member of an ethnic and religious minority.

“As evidenced by these corridos, Kennedy was in many ways a symbol of the Mexican-Americans’ aspirations for full rights and citizenship in the United States which they had been long denied due to racial and cultural prejudice and economic exploitation,” writes Dickey. “Mexican Americans in many ways could identify with Kennedy’s own struggle as a member of an ethnic minority – Irish Catholic – and his strivings for acceptance. And that identification, the bond of religion, and Kennedy’s tragic death itself seemed to crystallize Mexican American sentiment towards him which was visibly expressed by the writing, recording, and circulation of the corridos.”

Many Mexican Americans enshrined their love for Kennedy through the prominent display of his image on framed portraits and wall tapestries, ubiquitous in barrio living rooms throughout the Southwest. In one corrido, “Recuerdo Eterno” by Conjunto Florida, composer Willie Lopez ties the presidential portrait in his own home to Kennedy’s national fight for equal rights, rhyming the Spanish word for “picture” (retrato) with the term for “better treatment” (mejor trato).

Many Mexican Americans enshrined their love for Kennedy through the prominent display of his image on framed portraits and wall tapestries, ubiquitous in barrio living rooms throughout the Southwest. In one corrido, “Recuerdo Eterno” by Conjunto Florida, composer Willie Lopez ties the presidential portrait in his own home to Kennedy’s national fight for equal rights, rhyming the Spanish word for “picture” (retrato) with the term for “better treatment” (mejor trato).

Siempre guardo en la sala de mi casa,

A la vista tengo puesto tu retrato.

Tu pediste que al humano de otra raza,

Lo quisieran y le dieran mejor trato.

Interestingly, Lopez wrote this song to mark the first anniversary of Kennedy’s death in November 1964, the same month when Lyndon Baines Johnson was elected president. The song casts the election as an affirmation of the Kennedy legacy. Speaking for Mexican Americans, Lopez writes, “we all went joyfully to vote, remembering your greatness and your deeds.”

Sigue el mundo su marcha sin parar,

Gana Johnson también las elecciones,

Todos fuimos gustosos a votar,

Recordando tu grandeza y tus acciones.

The song closes with a pledge reflected in its title, “Eternal Memory.”

Un año que va pasando,

Y cien se pueden pasar,

Y los buenos mexicanos

No te vamos a olvidar.

The Frontera Collection has a total of 54 recordings about the Kennedys, almost twice as many for JFK (33) as for RFK (18), with another three dedicated to both brothers. Searching the Kennedy surname yields a total of 76 tracks, though the result is misleading. For example, the search includes songs on a label located in Kenedy, Texas, a city spelled with only one “n” but which is misspelled in the database with the double “n” of the family surname. Another tiny label is located on Kennedy Avenue in McAllen, Texas. And there are a couple of Tex-Mex numbers by popular country singer Johnny Rodriguez, produced by someone named Jerry Kennedy.

There are several Kennedy Corridos in the collection that might be overlooked because the famous name is not in the title. One song salutes the slain president as a soldier of peace (“Soldado de Paz”); one simply invokes the president’s memory (“Recordando al Presidente”); and another expresses sadness for the city made infamous by the assassination (“Triste Dallas”).

Not all of these compositions pretend to be corridos. The genres are not always listed on the labels, but those that identify a style include “Memoria Al Senator Kennedy,” listed as a vals (waltz), which is the only instrumental in the lot, featuring the mournful accordion of Pedro Ayala, with a traditional Tex-Mex conjunto. The Trio Internacional performs a celebratory huapango in homage to a living president, “A Kennedy En Vida,” in the lively folk style from the huasteca region along Mexico's Gulf Coast. On the other hand, Salvador S. Najera wrote and recorded a tribute to Robert F. Kennedy that is identified simply as a “canción,” or song, backed with a guitar trio, but which includes many factual details about the assassination, including a reference to his midnight victory speech just before he was killed. His song, “En Memoria a Kennedy,” was released on a small label based locally in Gardena, California.

One song, listed as a “lamento,” simply bids farewell to “our great president” (“Adios a Nuestro Gran Presidente”). It is one of the only Kennedy songs in the collection that is not performed by a Mexican or Mexican-American artist; it features legendary Puerto Rican cuatro player Yomo Toro and singer Luis Garcia from Ponce, Puerto Rico.

One song, listed as a “lamento,” simply bids farewell to “our great president” (“Adios a Nuestro Gran Presidente”). It is one of the only Kennedy songs in the collection that is not performed by a Mexican or Mexican-American artist; it features legendary Puerto Rican cuatro player Yomo Toro and singer Luis Garcia from Ponce, Puerto Rico.

A few other songs stand out, for their unique perspective or poetry.

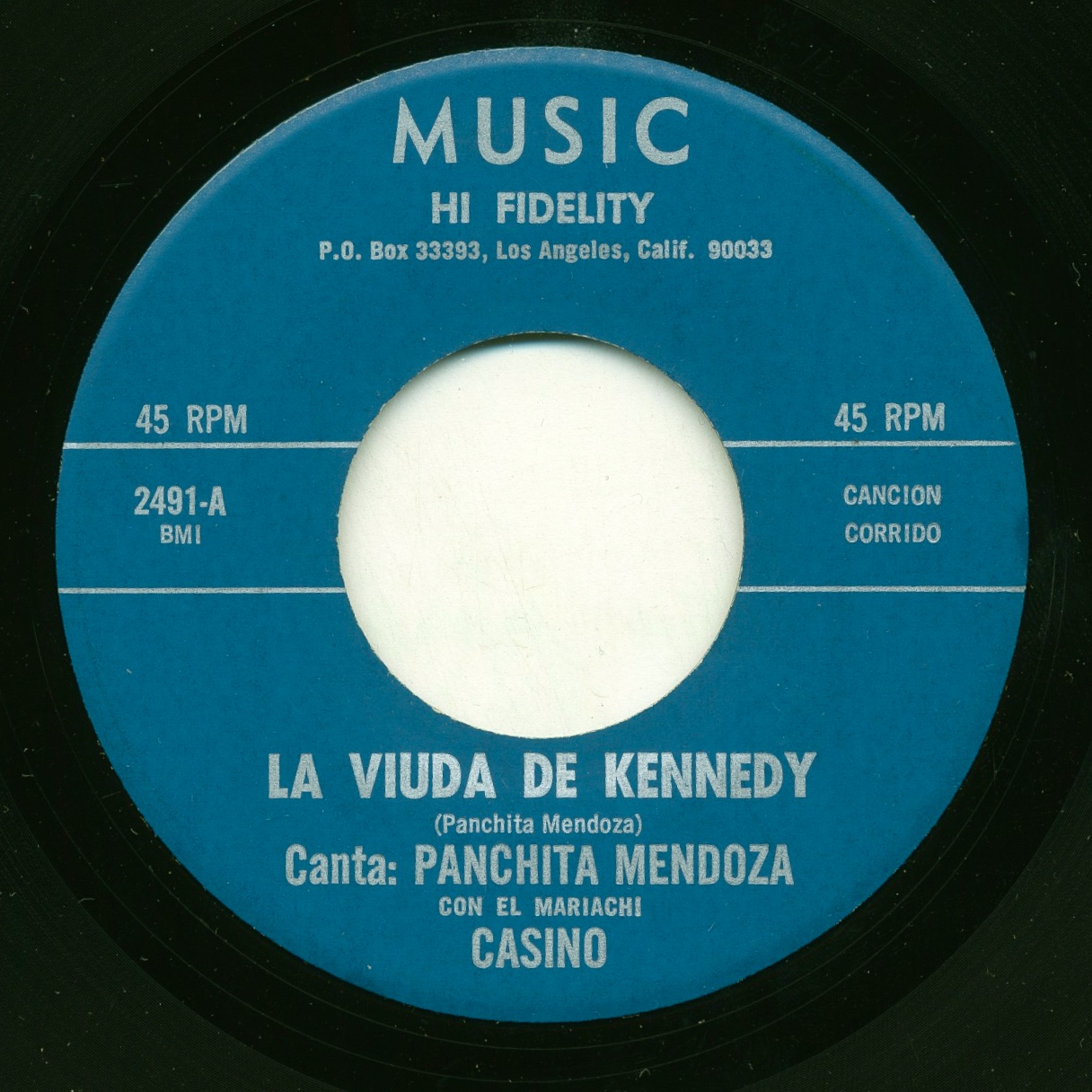

One song, for example, looks at the Kennedy tragedy from the vantage point of his widow, the late Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy. It’s appropriately titled “La Viuda De Kennedy,” by Panchita Mendoza, who also sings it with the backing of the Mariachi Casino. It is one of the rare, if not the only, composition about Kennedy written by a woman, and Mendoza makes the audacious decision of writing the lyric in Jackie’s own voice. “I am the widow of Kennedy,” the song starts. She goes on to describe herself as the dutiful and loving wife of a great leader (“cumplí sus deseos porque yo lo amaba”), who died in her arms. The mix on the recording – released by the Los Angeles-based Music Records – makes the lyric hard to distinguish because the singer’s high-pitched voice is masked by the over-powering mariachi.

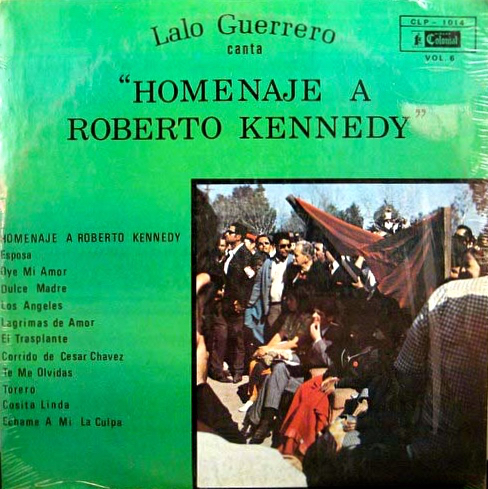

In his tribute to the slain senator, “Homenaje A Roberto Kennedy,” famed Mexican-American composer Lalo Guerrero makes a startling reference to the widow Ethel Kennedy, who was expecting the couple’s 11th child at the time of her husband’s death.

In his tribute to the slain senator, “Homenaje A Roberto Kennedy,” famed Mexican-American composer Lalo Guerrero makes a startling reference to the widow Ethel Kennedy, who was expecting the couple’s 11th child at the time of her husband’s death.

Bobby Kennedy, tus hjos te lloran.

Tu noble señora, ay! como te siente.

Con tu hijo en su vientre, no encuentra consuelo,

Y le pide al cielo, paciencia y valor.

A more traditional tribute to Jackie Kennedy was penned by the prolific composer José A. Morante, "Antorcha Eterna” (A la Viuda del Martir), performed by Rosita Fernández with the Mariachi Chapultepec.

Morante wrote another corrido, “Homenaje a J. F. Kennedy,” with a lyric that traces the arc of Kennedy’s career, from his military service, to his famous speech in Berlin and his outreach to Mexico. One verse makes specific reference to that disputed border territory.

México le abrió sus brazos, como a ninguno jamás.

Kennedy hizo justicia, regresando el Chamizal

The song, recorded on the San Antonio-based Norteño label by Los Conquistadores with backing by Los Arcos, is included in an Arhoolie compilation which encompasses relatively modern corridos, Ballads & Corridos 1949-1975.

Several tracks are dedicated to other historic figures of the period, both famous and infamous, including Martin Luther King, kidnapped heiress Patricia Hearst, and even convicted kidnapper and rapist Caryl Chessman, whose execution in 1960 at San Quentin became a cause célèbre for opponents of the death penalty.

The Kennedy Corridos are also the subject of a radio program in a series entitled The Mexican American Experience, archived by the University of Texas at Austin. Author Dickey contributed to the report, which includes quotes from interviews with some of the corrido composers. One of them is Dr. Jesús San Roman, a chiropractor from San Antonio, Texas, whose 45-rpm single on his own label offers a two-sided tribute to President Kennedy: a corrido with trio on Side A and a dramatic historical narration on the flip side, recited with a background of military marching music. Both are simply titled “El Asesinato del Presidente John F. Kennedy.”

In his interview, San Roman vividly relates his emotional reaction to the assassination, a feeling of shock and loss that infuses the works of many of his fellow corridistas.

“I went into the kitchen, I sat down on a chair, I put my head on my arm, and tears just started running down my face,” the composer says. “It was really a shock, and I don’t know why I felt it so much. I presume many, many people in the United States and around the world felt the way I did. But it really, really hurt me.”

– Agustín Gurza

3 Comments

Stay informed on our latest news!

Kennedy Corridos

by Geronima Garza (not verified), 03/04/2019 - 17:41Excellent article. Thank you

Kennedy Corridos

by Agustin Gurza, 07/02/2018 - 12:08Hi Chris: I really appreciate your praise for the articles we've been posting. Your words mean a lot to me. Your collection is such a fertile ground for material to write about, and I thank you for that too.

I made the corrections you noted. I’m not sure how I confused a huapango for a son jarocho, but I blame it on insomnia. I listened again and the song is unmistakably in the style from the huasteca region, as you correctly indicate. Thanks for catching that.

Agustin

Kennedy Corridos

by Chris Strachwitz (not verified), 06/29/2018 - 22:01Hi Agustin: what an amazing job you did on the subject at hand! Very impressive - and I just happen to come across it via FaceBook I think! I will call you to make a few corrections - main one: the spelling of composer's name is Jose Morante - in San Antonio! Many thanks - you are doing a superb job and hope you will get some more feed-back. One more: Huapangos are I believe native to the Huastecan region - not Veracruz Jarocho - they even try that falsetto singing! Cheers - Chris