the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center,

the Arhoolie Foundation,

and the UCLA Digital Library

Lalo Guerrero, the son of immigrants from a poor barrio in Tucson, Arizona, was a pioneering musician whose bilingual songs and bicultural persona earned him the honorary title "The Father of Chicano Music."

In a career that spanned seven decades, the versatile composer and performer wrote hundreds of songs in an astonishing array of styles, from romantic boleros to folkloric corridos, from comical parodies to rousing protest songs, from mambos to swing, rock, and cha cha chas. He had several international hit songs, appeared in movies alongside major Hollywood stars, operated a landmark nightclub in East L.A., and eventually earned the highest cultural honors awarded to entertainers.

But he is perhaps best known for his swing-era dance numbers that were prominently featured in the 1977 play Zoot Suit, reviving his career in mid-life and earning him new fans among a young, activist generation of Chicano artists. The ground-breaking musical by writer and director Luis Valdez dramatized the persecution and fighting spirit of the so-called “pachucos” of the 1940s.

"The play would not have been possible without his music," Valdez told me for the Los Angeles Times obituary I wrote when Guerrero died in 2005 at age 88. "So many focus on the negative side, but what Lalo captured was the joy of the pachuco experience, the playful vacilón, which no one else had done. That was something that was always unfailing with his work -- his great sense of humor and love for life."

The Early Years in the Barrio Viejo

Eduardo Guerrero Murietta was born on “a bitterly cold Christmas Eve in 1916,” to quote an opening line from his 2002 autobiography, Lalo: My Life and Music. He was delivered at home in Tucson’s Barrio Libre (now known as Barrio Viejo), with only his aunts in attendance.

The boy was named after his father, Eduardo Guerrero Ramirez, a boilermaker who had worked on steamships in the port city of Guaymas, Sonora. The elder Guerrero met and married Concepción Murietta in the historic mountain town of Cananea, site of violent labor strikes by copper miners in 1906. The couple was wed that same year, as street fights raged in town on the day of the nuptials.

“Mama told me that right in the middle of the ceremony, bullets came flying through the church windows and they had to dive under the pews,” Guerrero writes. “When the shooting stopped, they went back up to the altar and they got married and settled down to raise a family.”

With the official outbreak of the Mexican Revolution in 1910, the Guerreros crossed the border into Douglas, Arizona, part of a massive wave of Mexican immigrants fleeing the civil war. Guerrero’s father used his experience on Mexican steamships to land a job with the Southern Pacific Railroad and soon became the head boilermaker.

The couple already had four children when they arrived. Lalo was the first born in the United States, establishing from the start the cultural duality that defined his Chicano identity. He would be the fifth of 18 siblings, including triplets and double sets of twins, although only 11 survived infancy. Some sources report as many as 27 siblings, but Guerrero dismisses that unlikely figure as a tall tale told by his father. In any case, there were so many infant deaths in the family that, Guerrero recalls, “it seemed like every year there was another little white coffin in the living room.”

Guerrero draws contrasting portraits of his parents. His father was a stern disciplinarian who would beat him, sometimes naked, with a “special whip” of braided leather if he failed to do his chores. He wondered for decades why his father had been so harsh: “Maybe I just wasn’t macho enough for him,” he writes.

On the other hand, he was his mama’s pet, a shy “crybaby” who looked to her for comfort and musical inspiration. His mother was always cheerful, he recalls. She would sing and dance to music on a Victrola as she did her house chores, clicking her Spanish castanets and kicking her heels up high, her long braids flying and her hair unfurling as she twirled around the kitchen floor. To the neighbors, she was the beloved Doña Conchita. To her son, she was an everlasting positive influence, the one who taught him to play the guitar “and to love it and to wrap my heart around it.” He calls that “her biggest gift” to him.

"She taught me to embrace the spirit of being a Chicano," he says. "She would always say she was 'pura Chicanita.’ ”

The family’s Tucson barrio was so segregated, he writes, that the majority of Mexican-American residents never felt like a minority. Their ethnic community was on the wrong side of the tracks, but Lalo loved everything about it. He remembers the aroma of his mother’s freshly made, Sonoran style tortillas, the nature-boy thrill of swimming in the irrigation ditch, the singers serenading girls outside their windows, the mobile menudo vendors and the panaderías, the friendly waves of neighbors sitting on their front porches.

Years later, his nostalgia for the place would inspire one of his best known songs, “Barrio Viejo,” or Old Neighborhood, written “in memory of the world I knew as a child.” In the song, which he first performed in 1990, Guerrero laments the disappearance of the old barrio in the name of progress. Urban renewal plans in the 1960s called for the razing of many buildings, and a former Tucson mayor disparaged the area as a ghetto of "dirt, disease and delinquency."

But protests helped spare much of the neighborhood, including Drachman School, which Guerrero attended as a child. The old school building is now a residence for seniors named in his honor, Barrio Viejo Elderly Housing. (Guerrero performed the song with Mariachi Cobre in 2004, a year before he died, in what is considered his final public appearance.)

When he was five years old, Guerrero came down with a life-threatening case of smallpox, after his parents had refused the vaccination. The illness left him scarred for life, both physically and psychologically. He was “pockmarked and ugly,” he recalls, mocked by classmates with nicknames like Cacarizo, which means pitted or pockmarked, and Cara de Metate.

The boy felt rejected and lonely. Yet, he still dreamed of becoming a romantic crooner some day, like his heroes Rudy Vallée and Al Jolson. Guerrero loved the movies, especially musicals with Gene Kelly, Ginger Rogers, and Fred Astaire. He’d watch a film five or six times until he memorized the songs he liked. He taught himself the piano when he was ten; the first song he remembers playing was W. C. Handy’s “Saint Louis Blues,” which was featured in a film starring Charlie Chaplin and another starring Bessie Smith.

Guerrero credits his grammar school music teacher, Miss Davis, with encouraging him to perform and overcome his stage fright. Privately, the fifth-grader showed her how he had learned to tap dance by watching movies. Realizing her shy student’s desire to be onstage, she cast him in his first solo act, doing an Al Jolson impersonation for a school assembly. He felt transformed in his black hat, white gloves and black-face makeup, amazed that his scars were no longer visible.

“I was a smash!” he recalls. “When I heard the applause, I was hooked. Miss Davis had to drag me offstage that day, and I have been addicted ever since.”

The following year, as a sixth-grader, he entered a citywide classical music contest, along with two other Latino classmates. When they won, nobody was more surprised than Guerrero.

“We couldn’t believe it,” he recalls. “Three little Chicanitos from the wrong side of the tracks beat out all the kids from all over Tucson! We were so proud. I was only 12 but that contest had a great impact on me… That was when I really began to think that music was the road that I should take in my life.”

The first song Guerrero ever wrote was for his brother Raul, “my first buddy,” a little rascal who was a year younger. (In his book, the composer doesn’t name the song or say when he wrote it.) Raul died at age four, a painful loss coming shortly after the death of Guerrero’s beloved grandfather, a positive male figure in his life. Later, as a young man, Guerrero also lost his older brother Alberto, a boxer he called “my first hero.”

Despite the childhood traumas, Guerrero continued to explore his love of music, in all styles, Spanish and English. In equal parts, he loved Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys as well as Pedro J. Gonzalez and Los Madrugadores (the Early Risers). For hours, he’d stand at the window outside of The Beehive, a local bar patronized by blacks, absorbing the blues and swing styles that would play so prominently in his career.

“When it came to music, I was a funnel,” he writes.

At 14, Guerrero asked his mother to teach him to play the guitar and show him her favorite Mexican songs, like “La Adelita,” the revolutionary song about women warriors. Soon, the teenager had formed a trio with two high school friends, Manny Matas and Rudy Arenas, who called themselves Eddie, Manny and Rudy. They played backyard parties, got their own weekly show on the radio, and became “big shots in the neighborhood.”

Later, Guerrero started a duo which he considered his first professional experience because he actually got paid. He was a tenor and his younger partner, a neighborhood kid named Joe “Yuca” Salaz, was a baritone. They played guitars and harmonized beautifully, earning 25 cents an hour at first, raised to 50 cents when they got popular.

Eventually, the duo doubled, adding Yuca’s older brother Chole Salaz, and Greg “Goyo” Escalante. Now a popular quartet – four singers with four guitars – they started playing weddings, anniversaries and quinceañeras. They also performed regularly on local Tucson radio station KVOA, the Voice of Arizona.

One of their customers was a friend of Guerrero from high school, Gilbert Ronstadt, whose family owned a hardware store in town. Ronstadt had a young daughter who was thrilled to hear the music whenever the group came by his house to visit. Even at late hours of the night, the girl would rush downstairs to hear them play, sitting cross-legged on the floor, still in diapers. Her favorite song was “La Burrita,” about a little female donkey.

Many years later, Guerrero says he was surprised to hear her on the radio singing English pop music. The little girl with the big eyes had become a big star, Linda Ronstadt. In 1996, they sang “La Burrita” together at the Tucson International Mariachi Conference, with Ronstadt still doing the clip-clop sounds with her mouth, just as she had as a girl.

Expanding Horizons

At 17, Guerrero wrote one of his most famous songs, “Canción Mexicana,” incorporating traditional melodies in an ode to the country and its culture. He calls it “the most enduring song” in his repertoire.

“It was a kind of gift to the people of my old barrio to remind them that, even if we were poor, we had something to be proud of,” Guerrero says. “I have written hundreds of songs since then, but of all of them, ‘Canción Mexicana’ is number one in my heart.”

Despite his patriotic fervor, Guerrero had not yet been to Mexico. When his family briefly moved there, it was both a shock, and a cultural eye-opener.

In 1934, when he was a senior in high school, the Guerrero family moved to Mexico City, joining the Depression-era repatriation of hundreds of thousands of immigrants. Although their stay was brief, it was a tough adjustment for the teenager. He had to drop out of school before graduation, leave behind his first girlfriend, and adjust to life in a huge metropolis, “the other side of the Earth from Tucson.”

But the visit also opened new musical vistas for the aspiring artist.

“Almost as soon as I got off the train, a whole new world of music opened up for me with tremendous orchestras, beautiful melodies and rhythms like huapangos, sones, bambucos – music that I didn’t know existed,” he recalls. “The Mexican music that we knew up north was simpler, and maybe it was happier, but it was not half as beautiful as this music from the heart of Mexico.”

Guerrero also found a new musical idol, the revered composer Agustín Lara. He bought a notebook and wrote down song lyrics so he wouldn’t forget. “My music would never be the same,” he writes.

After three months, the family was back in Tucson. Concepción Guerrero was pregnant and not feeling well. (Guerrero claims his mother became the first woman in Arizona to give birth to a baby, his sister Mona, by caesarean delivery.)

For Guerrero, it was another abrupt dislocation requiring more adjustments. By then, his class had graduated and he refused to return to finish with younger students. So, he didn’t earn his diploma. Twenty years later, when he was well-known as an artist, he performed for an assembly at Tucson High School, and the principal surprised him with an honorary degree.

“I remember it like it was yesterday,” Guerrero says. “The students gave me a standing ovation, and I was so choked up that I couldn’t even say thank you.”

After returning from Mexico, Guerrero started playing again with his quartet, now under a new name, Los Carlistas. They got the name from a local youth club which itself was strangely named for an obscure, 19th century pretender to the Spanish throne, Prince Carlos. Guerrero never liked the name, nor having to explain it, but it was chosen by majority vote.

The band was so popular they started getting invitations to play “some fancy places” after being “discovered by the other side of town – the white folks.“ Seeking a wider audience, they were soon encouraged to move to Los Angeles by Frank Robles, a rabble-rousing state legislator from Barrio Viejo, who would become their manager. Robles got the group gigs on a popular morning radio show in L.A. and at local venues. They performed live at the historic California Theatre, now demolished, where they rubbed elbows with recording stars they admired, such as Las Hermanas Padilla and the duo Chicho y Chenco of Los Madrugadores.

When the group was booked to play Omar's Dome, an exclusive Hollywood nightclub, they were too broke to buy costumes. So they improvised a peasant look, buying yards of white muslin to sew shirts and pants with draw strings at the waist, making ponchos out of curtains and huaraches from old tires. They topped it off with straw hats from F. W. Woolworth.

Los Carlistas wore those very same costumes when they appeared in the 1937 film Boots and Saddles, starring Gene Autry. Although their part is uncredited, when the film played in Tucson, the band got marquee billing above the famous singing cowboy: Starring Los Carlistas with Gene Autry.

At the time, a wide variety of Latin music styles – from samba to tango, mambo to mariachi, conga to flamenco – was gaining widespread popularity among mainstream audiences. At the popular Club La Bamba, near Olvera Street in the heart of the city, Guerrero and the quartet serenaded the mostly white customers, strolling around their tables between floor shows. The place would become a hotspot for emerging Hollywood stars.

Guerrero watched one of these stars emerge on the La Bamba dance floor. She was part of a father-daughter show team known as the Dancing Cansinos, Eduardo and Margarita. Guerrero claims a bartender there invented the famed tequila cocktail and named it after the lovely Margarita, although others also take credit. Be that as it may, the young performer went on to become a huge Hollywood star under her stage name, Rita Hayworth.

Despite the gigs and the glamor of L.A., the Depression was still on and money was tight. Guerrero took a day job trimming the lining out of old rubber tires, a job that left cuts on his arms and hands. But his luck was about to change. A chance encounter on a downtown street would take his career to the next level.

First Recordings

Guerrero was walking down Main Street when a stranger, attracted by his fancy cowboy boots and white hat, stopped and asked where he was from. That man turned out to be the famed composer and producer Manuel S. Acuña, who like Guerrero had roots in Sonora. Their serendipitous meeting was the start of a long and fruitful recording collaboration.

Acuña worked as the A&R (artist and repertoire) man for Vocalion Records, located nearby. At Acuña’s request, Guerrero later delivered three songs to Acuña’s partner, Felipe Valdes Leal, another legendary producer of Mexican music. To his amazement, Guerrero later learned two of his songs would be recorded by the hugely popular Hermanas Padilla.

Those would be Guerrero’s first recorded compositions. The Frontera Collection contains the two songs on a Vocalion 78, recorded August 25, 1938, featuring the Padilla sisters with accompaniment by Los Costeños. The disc includes “El Norteño” (The Northener) backed by “Estamos Iguales” (We’re Even). However, only one side is credited to Guerrero. The label credits Acuña and Leal as songwriters on “El Norteño,” despite Guerrero’s claim that Acuña had given him a contract for both songs.

In his book, Guerrero doesn’t directly address the issue of credits on this recording, but he would complain on other occasions about being cheated out of royalties. Acuña also hired Guerrero to record four more songs with Los Carlistas. “The group got paid $50 per side,” he recalls, “and nobody mentioned royalties in those days.”

In his book, Guerrero doesn’t directly address the issue of credits on this recording, but he would complain on other occasions about being cheated out of royalties. Acuña also hired Guerrero to record four more songs with Los Carlistas. “The group got paid $50 per side,” he recalls, “and nobody mentioned royalties in those days.”

Frontera has all four of those early songs by the group on Vocalion 78s, all credited to Guerrero. One is “El Aguador,” a huapango, backed by “Cuestión De Una Mujer,” identified as a Canción Fox. The other disc features “¿De Que Murio El Quemado?” (What Did the Burned Man Die Of?) backed by “Así Son Ellas” (That’s the Way Women Are), the latter co-written with Chole Salaz. Los Carlistas went on to record a dozen more records in the next few months.

In those early works, Guerrero establishes the stylistic range that would mark his life’s work: humorous and romantic, folkloric and cosmopolitan, upbeat and slow tempo. His trademark became his versatility. Soon, he’d be adding English and Spanglish to his lyrics.

Wedding Bells and the Worlds Fair

The following year, Guerrero married his first wife, Margaret Marmion, the daughter of a hotel maid whose father had passed away. They had met at a friend’s wedding four years earlier, when he was 19, and she was 16. He serenaded her at the reception and asked her to be his girlfriend.

“I think that part of her attraction is that she didn’t look Mexican,” writes Guerrero. “She looked a lot like her Scottish-Irish father. Having suffered so much from discrimination, I wanted to spare my children. I thought their lives would be easier if they were lighter–complected than me.”

The wedding date – October 15, 1939 – had been announced at church in Tucson, but Guerrero worried he wouldn’t be able to pay for it. He had promised his bride-to-be that he would work in Los Angeles to raise the money, but it wasn’t easy. His quartet had disbanded so he teamed up with another musician, Lupe Fernandez, and the duo started playing at Café Caliente on Olvera Street.

By that time, he had forgotten all about the recordings made by Los Carlistas for Vocalion the year before. Then one day, Acuña, their producer, dropped by the club to tell Guerrero he had a royalty check waiting. He was shocked to learn the amount: $500. It was enough for a wedding dress and a fiesta, so he headed back to Tucson to get married.

Many years later, Guerrero found the lyrics of a song he had written for his wife. The words were on a piece of paper with a sketch of a charro he had drawn, but he couldn’t remember the melody. He didn’t know how to write music and he had no tape recorder, so the song was lost.

At this point, Guerrero had already written many other songs. So he decided to make a trip to Mexico City to get them recorded. The Mexican publishers liked the songs, but not the singer. They considered the U.S.-born Guerrero a “pocho,” a derogatory term for a Mexican who’s been Americanized, tantamount to a cultural traitor. It was a frustrating effort for the artist who considered himself “as good a tenor as anybody," as he once told a reporter.

“Talk about injustice,” Guerrero writes. “In the United States I was discriminated against for being a Mexican, and in Mexico I was discriminated against for being an American.”

He finally sold four songs to PHAM, Promotora Hispano Americana de Música, a publisher associated with Southern Music in the U.S.

He came home, waited, wrote letters. No response. After many months of inactivity, his high hopes that a star would record one of his songs were dashed, at least for the time being.

That busy year did bring a career high point, when Los Carlistas were chosen to represent Arizona at the 1939 New York Worlds Fair, which opened in April. They swapped their peasant outfits for black charro suits with silver trim, proudly promoting the state, and its warm climate, along with other iconic cultural symbols – desert cactus, Hopi pottery, and Navajo blankets.

The fair’s theme was “The World of Tomorrow.” At 19, Guerrero saw television for the first time, with tiny sets on display at the RCA, General Electric, and Westinghouse pavilions. And he marveled at a mockup of a future freeway, a decade before the first one was built in Los Angeles.

The climax of the trip was the group’s appearance at Radio City Music Hall, on the nationally broadcast show, The Major Bowes Amateur Hour. They sang “Guadalajara,” and got paid $10 plus an all-you-can-eat pass to a cafeteria across the street from the studio.

For Guerrero, the big thrill was “following in the footsteps of a boy who would be both a hero and a friend 50 years later.” He’s referring to Frank Sinatra, who had gotten his start in show business on the same show in 1935.

Guerrero always believed that his race – what he called “my dark, ethnic looks" – kept him from breaking into the American pop mainstream as a singer. But he was destined for a different breakthrough – as the country’s first Chicano star.

Guerrero always believed that his race – what he called “my dark, ethnic looks" – kept him from breaking into the American pop mainstream as a singer. But he was destined for a different breakthrough – as the country’s first Chicano star.

Guerrero developed his bilingual/bicultural identity in the crucible of racial conflict at home during World War II, when U.S. servicemen attacked Mexican-American youth on the streets of Los Angeles. Guerrero, who was among the persecuted victims in the so-called Zoot Suit Riots, emerged as the voice of his generation. His snappy, swing dance tunes, peppered with pachuco street slang, would finally put him on the pop culture map.

In 1939, as the Depression was winding down and a new world war was heating up, Lalo Guerrero was still a struggling musician seeking to make his mark. He was newly married and dirt poor, with a son on the way and work hard to come by, keeping the young family on the move from gig to gig.

In 1939, as the Depression was winding down and a new world war was heating up, Lalo Guerrero was still a struggling musician seeking to make his mark. He was newly married and dirt poor, with a son on the way and work hard to come by, keeping the young family on the move from gig to gig.

In his autobiography, Lalo: My Life and Music, Guerrero called this period “our gypsy years.” Yet, the swing-music decade of the 1940s would also bring stardom and some stability to the young performer.

Guerrero and his new bride, Margaret, were married in their hometown of Tucson on October 15, 1939. That same evening, the couple drove back to Los Angeles where they were living and where Guerrero was performing with his duo at Café Caliente on Olvera Street. But he lost the job the very next night when Lupe Fernandez, his hot-headed partner, got in a dispute with the owner. Fernandez punched the boss, who chased him out of the place with a butcher knife. Guerrero was invited to continue on his own, but he didn’t yet feel confident as a solo act.

The couple returned temporarily to Tucson, where their first son, Edward Daniel, was born at a birthing center called the Stork’s Nest. The constant hunt for work, however, would soon take them back to Los Angeles, where they lived in an apartment so tiny there was no room for a crib. Their baby boy, a future stage actor and TV producer, slept in a dresser drawer.

Guerrero soon reconciled with his former partner. Fernandez had formed his own duo with a musician from Tijuana, Mike Ceseña, “a wonderfully talented young man, a good guitar player with a great voice.” The three formed a trio and started playing at a Phoenix restaurant called El Chico.. Guerrero had gone to Arizona without his family but before long, his wife insisted on joining him, even though they had to live temporarily in an adobe shack with dirt floors.

“I don’t care if we have to sleep under a bridge as long as we’re together and we have milk for the baby,” Guerrero recalls his wife saying. “Maybe another woman would have insisted that I go out and get a real job, but through all those hard years, Margaret understood that my music was my life.”

Tragedy soon struck the new trio when Ceseña drowned while swimming in an irrigation ditch. Guerrero blamed Fernandez for the accident, because he had taunted his bandmate to jump in. Once again the partners parted ways, bitterly this time.

“As soon as we had buried Mike,” writes Guerrero, “I said to Lupe, ‘I quit, man. I’m not going to work with you anymore.’ Then I told Margaret, ‘Get the baby. We’re going home.’ ”

Back in Tucson, Guerrero began performing solo at a restaurant called El Charro Café, playing nine hours a night, six nights a week, for five dollars a week, and living on tips. He also got a bit part in the 1940 film Arizona, an Oscar-winning western starring William Holden. Guerrero was barley recognizable in his brief appearance, sitting on a horse, wearing a black wig, made up “to look even more like an Indian than I actually did.”

The start of World War II forced Guerrero to take that day job he had been avoiding, since he hoped to avoid the draft with war-related employment. After the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, he moved his family to San Diego, where he went to work for Consolidated Aircraft (later Convair), making B-24 Liberator Bombers. On weekends, billed as Eddie Guerrero, he’d play at the Mexicali Club where, according to a newspaper review at the time, “the tenor troubadour was held on stage by wild applause from the audience, which just wouldn’t let him stop.” He also started touring with the USO, performing with an 18-piece orchestra at military hospitals and naval bases.

One evening in San Diego, Guerrero got a thrilling surprise when he heard his song “Canción Mexicana” played on the radio by Lucha Reyes, a top Mexican vocalist at the time. He recalls shouting for his wife to listen, and they jumped up and down together with excitement. He thought his big dream had come true: a big star had finally recorded one of his songs.

His heart sank, however, as soon as he crossed the border and bought the record in Tijuana. The album credits listed Lucha Reyes – not Lalo Guerrero – as the songwriter. Intent on confronting the publisher, Guerrero immediately hopped a train to Mexico City, fuming all the way. During the four-day trip, the sound of the train wheels seemed to torment him with the rhythmic repetition of a taunting phrase: “They’re trying to steal your song. They’re trying to steal your song.”

It turned out to be a convoluted misunderstanding. As Guerrero explains, Reyes had heard the song in Los Angeles, while performing at the historic Mason Theatre located on Broadway across from the Los Angeles Times building. Reyes shared the bill with a trio that included one of Guerrero’s former partners, Luis Moreno. When the headliner inquired about the song, Moreno jokingly claimed he had written it, and offered it to her as a gift, never thinking she’d actually record it.

Guerrero never talked to Reyes directly about the copyright confusion, and he never knew if she was even aware of the mix-up. He was angry at first, but later realized his song may have never been recorded otherwise. It was one of those numbers he had sold to PHAM in 1939, and the publisher didn’t even know that Reyes had recorded it for RCA until Guerrero showed up in person to complain. In fact, if not for his partner’s prank, Guerrero muses, “Canción Mexicana” may have gathered dust in a filing cabinet along with his other ignored numbers.

The composer’s intervention, however, eventually corrected the credits, although he doesn’t mention the remedy in his book. The Frontera Collection has two versions of the song by Reyes on 78-rpm discs, both with the Mariachi Tapatío. In one (Victor 70-7099), Reyes is indeed credited as the songwriter. But on the other, presumably later release (RCA Victor 23-6398), Guerrero is properly credited as composer. He also gets credit on a third version from the archive, a 45-rpm single also on RCA Victor, released at least a decade later.

Lesson learned: It pays to aggressively defend your copyrights.

Pachucos Take Center Stage

After the war, Guerrero moved back to Los Angeles and started working again at Club La Bamba, this time as a solo act. In those heady postwar days, the place was patronized by Hollywood celebrities, including actress and pioneering female director Ida Lupino, as well as up-and-coming stars Ricardo Montalbán and Anthony Quinn, both fellow immigrants from Mexico.

In 1946, Guerrero was contacted at the club once again by Manuel Acuña, the record producer who had discovered him a decade earlier on an L.A. sidewalk. Acuña was now working with Imperial Records, founded that same year by Lew Chudd, who would soon turn the label into a pioneering force in rock and R&B, with acts like Fats Domino and Ricky Nelson. But at the time, Acuña said Imperial was looking for a Mexican trio to record, and Guerrero was recruited to put one together.

Thus was born El Trio Imperial, formed by Guerrero and two friends, Mario Sanchez and Joe Coria. According to his autobiography, Guerrero recorded some 60 songs for the label in the ensuing months, either with the trio or with a mariachi, at $50 per side. The Frontera Collection contains 67 recordings by Trio Imperial in a variety of styles, many composed by Guerrero himself.

A few of those songs – “La Boda de Los Pachucos,” “El Pachuco,” “El Pachuco y El Tarzan” – spotlight Guerrero’s trademarks as a composer: his street-savvy satires, character dialogs, and his command of caló, the Spanglish slang of the so-called pachucos, the flashy Mexican-American rebels of the 1940s. Guerrero didn’t know it yet, but those pachuco sensibilities would eventually be the key to his biggest success, as part of the future musical Zoot Suit.

At the time, Guerrero and his producer were itching to push beyond the boundaries of the trio’s romantic/ranchera format. So they decided to form a modern dance band, with tropical and jazz influences. Guerrero recruited the best players he had met in LA’s hopping Latin nightclub scene, and he formed a five-piece combo called Lalo y Sus Cinco Lobos. They were Pete Alcaraz, David Lopez, Frank Quijada, Carlos Guerrero and Alphonso Rojo.

Guerrero says he was looking for good musicians who could also get along together. Apparently, he made the right choices; his quintet of wolves would stay together for 20 years.

At first, the band was created to record, but it also became popular as a performing act. Their first engagement was at Club El Acapulco on Los Angeles Street. It was Guerrero’s first gig as a bandleader, and it lasted for almost a year. They went on to play at many other venues.

The L.A. nightclub scene at the time “was very diverse and very exciting,” Guerrero recalls. Places were packed with music lovers and dancers every night of the week. Venues featured top acts from Mexico, such as the legendary Mariachi Vargas de Tecalitlán or the urbane orchestra of Luis Arcaraz. They also got an infusion of the best Caribbean dance music from the East Coast, with acts such as Tito Puente and Perez Prado thrilling fans at dance clubs El Trocadero, Ciro’s, and Coconut Grove.

One of the clubs, El Hoyo (The Hole) on Main Street, was patronized primarily by pachucos, dressed in jazzy zoot suits and dancing jitterbug. During the war years, pachucos were targeted as unpatriotic by U.S. servicemen, who attacked and disrobed them on the streets in what became known as the Zoot Suit Riots. Guerrero, who was still living in San Diego at the time, recalls the impact of the social unrest: “We could feel the vibrations of the violence, like being on the edge of an earthquake.”

For Guerrero, pachucos represented “the epitome of ‘cool’ before the word cool was ever used.” And as a performer, he was popular with them because he played the boogie-woogie and swing music they liked, and he could speak their language, using their Spanglish slang both in lyrics and in conversation.

In one early parody, however, Guerrero decries their degradation of proper Castilian Spanish. Titled “Nuestro Idioma” and featuring El Trio Imperial, the song calls Spanish the world’s most beautiful language, used for “making love to a lovely lady, speaking to your mother, and praying to God.” In a dialog segment, pachucos are heard speaking in caló, which mystifies the songwriter who asks listeners to help translate. And in a genteel voice in perfect Spanish, the singer begs forgiveness from “our ancestors” for “having destroyed such a lovely language.” Considering Guerrero’s prominent use of the street slang, his song can be seen as a spoof of Castilian purists.

In one early parody, however, Guerrero decries their degradation of proper Castilian Spanish. Titled “Nuestro Idioma” and featuring El Trio Imperial, the song calls Spanish the world’s most beautiful language, used for “making love to a lovely lady, speaking to your mother, and praying to God.” In a dialog segment, pachucos are heard speaking in caló, which mystifies the songwriter who asks listeners to help translate. And in a genteel voice in perfect Spanish, the singer begs forgiveness from “our ancestors” for “having destroyed such a lovely language.” Considering Guerrero’s prominent use of the street slang, his song can be seen as a spoof of Castilian purists.

Guerrero wrote more than a dozen “pachuco songs” with the trio, many in corrido or ballad style. But the ones that became classics and established his legacy were those recorded as dance numbers with his Cinco Lobos. Three decades later, four of those tunes would make it to Broadway and the silver screen, as featured in the 1978 musical Zoot Suit by Luis Valdez. The songs had come to Valdez’s attention via ethnomusicologist Philip Sonnichsen, who had taped and archived the music, and later shared it with the playwright, according to Guerrero.

The Frontera Collection contains all four songs from the play. “Vamos a Bailar” backed with “Chicas Patas Boogie” are on a 78-rpm disc (Imperial 458), performed by Guerrero and his orchestra. “Los Chucos Suaves” (Cool Cats) and “Marijuana Boogie” are featured on the film’s soundtrack album, with lead vocals by actors Edward James Olmos and Daniel Valdez, the playwright’s younger brother.

By the late 1940s, the pachuco scene faded and Guerrero moved on. In 1949, he and Margaret had their second son, Mark, now a musician and writer based in Palm Springs. The 1950s would bring more hits in other styles for Guerrero, but he would never leave the pachucos behind.

“In reality,” he writes, “the pachuco mystique never really went away; the shadow of the zoot suitors hung over us. The music faded, the styles changed, but they never disappeared completely.”

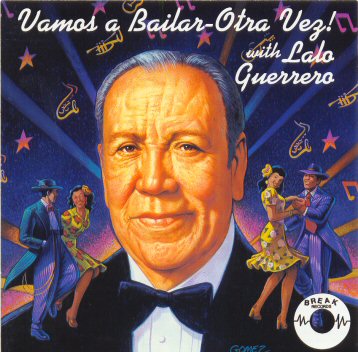

Two decades after the success of Zoot Suit, Guerrero, at age 83, re-recorded tunes from the play, among other songs, for a 1999 CD on Break Records, entitled Vamos a Bailar – Otra Vez! It was produced by Ben Esparza, and featured a 12-piece band of top L.A. studio musicians, including Justo Almario, who was co-producer, on flute and sax.

On the Road and On the Hit Parade

In 1947, just after he turned 30, Guerrero managed to achieve one of his long-time dreams: he finally made a record in English, under the stage name Don Edwards. In his smoothest croon, he recorded two bilingual tunes for Imperial Records,“To-Day and Always” and “Florecita,” backed by Mark Wilson and His Orchestra. But the record didn’t sell, dashing his hopes of crossing over to the mainstream, English-language market.

“I had a beautiful, clear voice, and, if I may say so, I did a good job on that record, but I was years ahead of my time,” he wrote. “In the forties, nobody could even conceive of a Mexican-American with the face of a cactus singing “Tiptoe Through the Tulips,” or whatever. The sales were only so-so, and I went back to Spanish.”

In 1948, Guerrero got lucky with a song called “Pecadora” (Sinner), by Mexico’s most esteemed composer of the era, Agustín Lara. But Lalo’s big break was another man’s misfortunate. When a star vocalist from Mexico started drinking and missing recording sessions for Imperial Records, producer Acuña asked Guerrero to fill in as a soloist on the song, which became his first solo hit. (Curiously, the 78-rpm recording on Colony Records does not include a composer credit for Lara on the label.)

Back home in Tucson, people gave Guerrero “a hero’s welcome,” with a dance at Wetmore’s Ballroom.

“In those days, it was very difficult to get on record as a soloist and there had never been a local boy – black, white, or brown – who had done it,” he recalls, “My mom was there, my brothers and sisters, and my friends. I sang for them, and it was a wonderful, wonderful experience to come home a success.”

Guerrero’s relationship with Acuña as producer would last 30 years, working together on recordings for different labels. Acuña, who was also a composer and arranger, would select songs he believed were suited for Guerrero, and his instincts were most often right.

The success of “Pecadora” boosted Guerrero’s record sales throughout the Southwest. To capitalize on his newfound popularity, he soon hit the road. At a show in Mexicali, he met a comedian and former circus clown named Francisco “Paco” Sanchez, who proposed a partnership for a travelling road show. Sanchez had toured with Barnum & Bailey, and knew where to find places with Mexican-American audiences starving for entertainment.

Soon, the two men were touring towns throughout the Southwest, presenting their vaudeville-style act. It featured the comedian, a mariachi, and the lead singer, all packed into Paco’s Packard and Lalo’s Pontiac.

Guerrero returned home with earnings of $80,000, part of which he used to buy a home in East Los Angeles. Sanchez went on to successfully run for state office in Colorado.

Itching to repeat his touring success, Guerrero soon joined forces with Teddy Fregoso, a Mexican composer and publicist who had once trained to be a bullfighter. Fregoso – who would go on to become a popular L.A. deejay with his own radio station above the El Capitan Theatre in Hollywood – set up the tour and made himself the emcee. Guerrero and his band packed the Mexican ballrooms wherever they appeared.

Guerrero soon learned how to time his tours to draw peak audiences. He played wherever farmworkers migrated, to harvest onions in June or cotton in September. “The field workers followed the crops, and so did I,” he writes.

Luck also followed Lalo on the road.

One night in Denver, his band was booked at the Rainbow Ballroom as the opening act for Trio Los Panchos, the celebrated romantic crooners from Mexico City. Afterward, they approached Guerrero and asked him about a song they liked but had never heard before, “Nunca Jamas” (Never Again), written by Guerrero to denounce spousal abuse. The famed trio wanted to record it, so Guerrero wrote out the lyrics, never thinking they would actually do it. Months later, back in Los Angeles, he was thrilled to hear his song coming from a jukebox late one night, performed by none other than Trio Los Panchos.

“Of all the songs I’ve written, the two that were first recorded almost by accident, “Canción Mexicana” and Nunca Jamás,” are the ones that have been the biggest hits over the years,” he says.

In the Frontera Collection, the version of “Nunca Jamás” by Trio Los Panchos was originally recorded by Columbia in Mexico, but released on New York’s Seeco label, for the U.S. The archive also contains a couple of versions by Guerrero himself: a 45-rpm single with Mariachi Los Camperos on the Colonial label, owned by producer Acuña, and an older 78 with an unidentified mariachi on RCA Victor, with the title translated as “Never, Never.”

As a bandleader, Guerrero felt protective of his musicians. He especially sympathized with his drummer, Frank Quijada, who was blind in one eye. Guerrero recalls that some bands wouldn’t hire him because his bad eye was also crossed “and he didn’t look good on stage.” But Lalo didn’t care about looks; he had hired Quijada because “he was a very fine drummer.”

Guerrero also admired the percussionist’s devotion. For one song about a shoeshine boy, “El Bolerito de La Main,” Quijada recreated the sound of a snapping shoeshine rag by taking off his pants and slapping his bare legs. In the studio, after multiple takes, the drummer’s skin was red from repeating the sound effect, as many times as it took. You can hear Quijada’s slapping effects throughout this recording titled simply “El Bolerito,” a boogie-woogie on Imperial featuring Lalo Guerrero y Su Sexteto.

Guerrero and Quijada were roommates on the road, and he tried to watch out for his one-eyed drummer, worried that he might trip and fall off the stage. Quijada also supported his boss, and was thrilled when they played to full houses.

When Quijada contracted cancer in his 30s, there was nothing Guerrero could do to help. The band had to go on the road without him. At a stop in Santa Fe, they got word that their drummer had died. His widow called and related the musician’s last words: “Lalo, look! The place is packed, Lalo. Isn’t it wonderful!”

The drummer had passed away feeling the glow of the band’s success.

The Fabulous Fifties

The 1950s was a big decade for Guerrero.

He continued to land small roles in major Hollywood films. The musician didn’t consider himself much of an actor, but directors would call to cast him now and then because, he surmised, they liked his looks: “tall and slender with sleek black hair, not quite Indian, not quite Spanish – an Anthony Quinn type.”

He appeared in the film His Kind of Woman (1951), set in a Mexican luxury resort and starring Robert Mitchum and Jane Russell. Guerrero appears in one scene strumming his guitar to the vocals of the voluptuous Russell, who is said to have had an affair with millionaire Howard Hughes, the film’s executive producer. In his autobiography, Guerrero recalls a humorous anecdote on the set. As Mitchum makes his entrance, the director interrupts the shoot because the actor was ignoring his sexy co-star. Mitchum should naturally be ogling Russell as he approached, the director instructed. To which Mitchum replied: “Oh, I don’t know about that. Did you notice the ass on the guitar player?”

The crew cracked up, and Guerrero says he didn’t mind being made the butt of the joke. But Russell was miffed, and huffed off the set.

Guerrero still dreamed of making it in Mexico, something no other Mexican-American performer had done. So in the mid-1950s, he took his wife and sons to Mexico City, moving into a room at the Hotel Regis, in the heart of the city’s historic downtown. Soon, it was clear he had hit another dead end. The record deal didn’t pan out, the press was uniformly critical of his perceived “pocho” arrogance, and his wife was losing patience with his endless nights of carousing with fellow musicians.

Margaret issued an ultimatum: he could stay in Mexico City, but she was going home with the boys. Guerrero relented. The day after they left, an earthquake destroyed the building where they had been living. News reports of the quake, which hit the capital shortly after 7 a.m. on Sept. 19, 1985, mention the complete collapse of the Hotel Regis, which also caught fire from a gas leak. Guerrero credits his wife with possibly saving their lives.

Pancho Lopez and the Appeal of Parodies

Back in the states, it was another serendipitous event that led to one of Guerrero’s biggest hits, in both English and Spanish.

Guerrero was on his way to work one day when he overheard some Mexican boys in his neighborhood improvising Spanish lyrics to one of the most popular songs of the day, “The Ballad of Davy Crockett," which had premiered in 1954 on the television series, “Walt Disney's Wonderful World of Color.” In the chorus, the kids had replaced the American folk hero with a Mexican one, singing, “Pancho, Pancho Villa….”

That inspired Guerrero to come up with his own Spanish lyrics for the ubiquitous tune, which became a chart-topping hit for Disney in 1955. The original song, which tells the tale of Crockett and his coon-skin hat, was featured in both TV and film productions about the “injun” fighter, played by actor Fess Parker, who died at the Alamo.

Guerrero turned the narrative ballad into a playful spin-off titled “Pancho Lopez.” It was about a kid who was born in Chihuahua in 1906, got married when he was seven, went off to fight the revolution at eight, and was dead by nine. The moral: Slow down, you’re living too fast.

His parody became a smash throughout the Southwest and Latin America. In Mexico, there was even a movie made based on Guerrero’s satirical character, “Pancho López” (1957), starring singer Luis Aguilar. Once again, Guerrero complains he was never paid for the use of his song in the film. The IMDB, the authoritative movie database, does not credit Guerrero in its listing; Manuel Esperón, the prominent and prolific Mexican songwriter, is credited as the movie’s musical director.

“I never got a penny for that,” he writes of the film. “It still burns me up to think that, even when it played in San Diego, the producers never got in touch with me. They didn’t even offer me a free ticket!”

At one point, Guerrero took a demo of the song to Hollywood record distributor named Al Sherman (not to be confused with satirical songwriter Allan Sherman). The distributor, who didn’t speak Spanish, guaranteed Guerrero a million-seller, if he came up with English lyrics for the song.

As Sherman predicted, the English version also became a hit in 1955, selling 750,000 copies. It earned Guerrero a write-up in Time Magazine and guest appearances on popular TV shows, including Tonight with Steve Allen and a show hosted by Art Linkletter.

The song’s mainstream success caught the unwanted attention of none other than Walt Disney, whose Wonderland Music Publishing owned the rights to the original Davy Crockett melody. Guerrero recalls being summoned to a meeting with the celebrated producer, who had launched his new Disneyland theme park that same year. Disney, he knew, would be claiming his legal copyright.

“Pancho Lopez” had been released on Discos Real, a label founded, also in 1955, by Guerrero and two business partners, recording engineer Jimmy Jones and investor/businessman Paul Landwehr. The company, however, had failed to get the needed permission to use the Disney-owned tune.

In his book, Guerrero recalls he and his partners being summoned to a meeting at Disney’s Burbank studios. The nervous trio of label execs feared they’d be sued and ruined for their infringement. But “what really shook us up,” he recalls, was being immediately escorted into Disney’s private office, coming face to face with the animation mogul, flanked by two lawyers and his head of song publishing.

Disney was cordial and congratulated Guerrero on his “clever” lyric (“what a compliment!”). But he quickly confronted them with their failure to get the proper clearance.

“Yes sir, we realize that,” said Guerrero, who had been selected as Disco Real spokesman, “but we really didn’t expect to sell more than a few thousand copies. And we thought that nobody would ever know about it, including you.”

Guerrero thought he detected a flicker of a smile on Disney’s lips. Then, the renowned creator of Mickey Mouse laid down the options: they could either go to court, or they could split the proceeds 50-50.

“I couldn’t believe my ears,” Guerrero recalls. “Real fast, I said, ‘We’ll take it.’ ”

Interestingly, there are different credits on two recordings of the song, both 78s, in the Frontera Collection. In one, Discos Real 218-A, Guerrero shares songwriting credits with George Bruns and Thomas W. Blackburn, the original composers of the Disney song. But on another version, Discos Real 1301-A, only Bruns is listed as co-writer with Guerrero. Presumably, Blackburn – who wrote the original lyrics that today would be considered racist – was dropped because it was Guerrero’s English lyrics, not his, that were used.

The archive also contains another Disney number with a Latin twist, “Mickey Mouse Mambo,” based on the theme song from the Mickey Mouse Club television show, with lyrics by lead Mouseketeer Jimmie Dodd. The Real Record recording, (both on 45-rpm and 78-rpm singles) identifies the artist with an official nickname: Lalo (“Pancho Lopez”) Guerrero. L.A. salsa fans will be interested to note the singer’s backup orchestra is led by Chico Sesma, a pioneering salsa deejay and concert promoter in Southern California. In this case, the label was careful to credit the publisher, Walt Disney Music.

The contract between Disney and Discos Real turned out to be quite lucrative for the “Pancho Lopez” partners, who split their profits three ways. With his share, Guerrero was able to open up an East Los Angeles nightclub that would set the stage for the next phase of his career, as host of the popular venue for more than a decade.

Meanwhile, “Pancho Lopez” spawned other popular cross-cultural parodies in the years that followed: There was “Elvis Perez” (“when he plays the guitarra, he don’t sing Guadalajara”); "There’s No Tortillas," to the tune of Presley’s "It's Now or Never" ("O Sole Mio"); "Tacos for Two," a send-up of the pop standard "Cocktails for Two;" and "Mexican Mamas, Don't Let Your Babies Grow Up to Be Busboys," a riff on a famous country song about mothers and cowboys.

The Frontera Collection contains a 1981 compilation of his humorous spin-offs, Parodies of Lalo Guerrero, featuring new recordings with his son, Mark, and members of Los Lobos, the famed East L.A. rock band. The album includes Guerrero’s most beloved parody, "Pancho Claus," which imagined a Mexican cousin of Santa Claus in a cultural twist on “The Night Before Christmas.” It also includes his automotive twist on Tony Bennett’s classic, “I Left My Car in San Francisco.”

“I can Mexicanize anything,” writes Guerrero, who later would perform as Santa Claus in East L.A. every Christmas. “These songs were all written just for fun, but later I sometimes used humor to make a statement when I saw something that wasn’t right in our society.”

One of his parodies attracted national attention. Guerrero transformed Tennessee Ernie Ford’s “16 Tons,” about the crushing work of coal miners, into a “housewife’s lament” called “Sixteen Pounds,” referring to a wife’s daily load “of dirty old clothes.” On his popular television show, Ford performed Guerrero’s version, with the refrain: “Your husband comes home and whaddya get? How come my dinner ain’t ready yet?” A version of the song was recorded on Discos Real by singer Gloria Becker, who later, as an agent, would play a pivotal role in the final chapter of Guerrero’s career.

Often, success has a down side. Discos Real was disbanded in acrimony, barely two years after it was founded. Prompted by his wife’s suspicions, Guerrero had discovered that one of his partners was draining company funds on personal expenses.

Later, some 20 years after the success of “Pancho Lopez,” activists in the emerging Chicano Movement started taking shots at the Crockett parody as racist and stereotypical. They cited lyrics they found offensive, describing the character as a fat and lazy boy who came to the US as a “wetback” and opened up a taco stand on Olvera Street. Editorials slammed the song as “degrading to Mexican Americans,” Guerrero recalls. (In 1966, Trini Lopez, the popular Mexican-American singer famous for his crossover hits, recorded the song for his Reprise Records release, “The Second Latin Album.”)

Although Guerrero didn’t completely agree with his critics, he said he stopped singing the song in public after that. He allowed that “maybe it does come out racist” in English.

“Over the years, some of my songs have offended different groups: Chicanos, gays, women,” he writes. “I have never intended any malice or meanness, but I’ve never worried much about being politically correct. I just find humor in everything.”

A Spanish-Speaking Martian and Three Singing Squirrels

In 1959, at the close of an already prosperous decade, Guerrero came up with another novelty concept that would amplify his success, both domestically and internationally. As before, he had no idea how big his new creation would become.

The idea came to him, Guerrero writes, at the dawn of the space race. It was big news in 1957 when the Russians launched Sputnik, the first unmanned satellite, into space. The Americans followed suit, and the competition for space dominated the news at least for the next decade.

Guerrero says that made him wonder what would happen if a Martian came to Earth first. In the back of his head, he kept musing about the funny scenarios that would ensue from interaction with a space visitor.

At around the same time, Guerrero was in Jimmy Jones’ studio for a recording session when his vocal was played back on fast forward. Guerrero asked the engineer to come up with a way to deliberately record “this little high-pitched voice,” that sounded to him like a Martian.

Guerrero says he quickly dashed off the lyrics to a song about a Martian who comes to Earth with green skin, a single eye in the middle of his forehead, and speaking Spanish. The Martian with the squeaky voice lectures Earthlings to stop sending their stuff into space – or else.

The song, Un Marciano en La Tierra, became a hit throughout Latin America. It was even a smash in Havana, just before Fidel Castro took over. Guerrero decided to capitalize on the novelty and came up with a whole new act for children, Las Tres Ardillitas, the Three Little Squirrels. He named them Pánfilo, Anacleto and Demetrio, and gave each of them a personality with a unique squeaky voice, played by him and a rotating cast of voice actors, including his son Mark, who also wrote the music for 11 of the children’s tunes.

In the early 1960s, Guerrero started recording albums by Las Ardillitas on his Colonial label. Then in 1966, Acuña, his longtime producer, sent samples of the records to EMI Capitol de Mexico, which signed the act right away.

“After all those years of banging on doors,” Guerrero writes, “I finally got to record in Mexico City… as a squirrel.”

Guerrero milked the franchise for 20 years, recording in Mexico one or two albums per year, including Christmas LPs. This time, there would be no controversy about his lyrics. The squirrels were cute and wholesome. They sang to children about good manners, respect for parents, and proper behavior at school, teaching them “right from wrong… with humor and a happy melody.”

Like the Disney song, however, Las Ardillitas presented a legal challenge. Guerrero states that he received a letter regarding a similar act that was also very popular, called Alvin & The Chipmunks, created by Ross Bagdasarian Sr., who performed as the chipmunk’s adoptive father under the stage name, Dave Seville. The Chipmunks debuted as a novelty record in 1958, with Bagdasarian performing as the squeaky chipmunk trio by speeding up his own taped voice on playback.

The letter claimed that Las Ardillitas, which debuted the following year, was a chipmunk knock-off and ordered Guerrero to cease and desist. But Guerrero’s lawyer replied that creating “little voices for animals” was common, so nobody could claim an exclusive on the concept. Some sources say that the case was settled out of court, but Guerrero writes in his book that the matter was simply dropped because he never heard from Alvin and the Chipmunks again, suggesting there never was a legal court filing.

Technically, the idea of creating high-pitched vocals by speeding up tape playback was not original. Guerrero’s Martian was preceded by another extraterrestrial novelty song, “The Purple People Eater," by Sheb Wooley, released by MGM. The song, which also features a squeaky-voiced creature from outer space, hit No. 1 on the Billboard pop charts in the summer of 1958. Earlier that year, Bagdasarian himself had a hit with yet another sped-up, squeaky vocal, “The Witch Doctor.”

In his defense, Guerrero says his squirrels and Bagdasarian’s chipmunks became popular around the same time, and “I really don’t know who was first.”

Throughout the 1960s and ’70s, some two dozen albums of Las Ardillitas were released, and Capitol Records later reissued the act on CD. They became popular with the grandchildren of the original fans, many of whom had never heard of Lalo Guerrero, but could readily name by heart Pánfilo, Anacleto and Demetrio.

Lalo’s Nightclub

In 1957, Guerrero was between novelty hits, post-Pancho Lopez and pre-Las Ardillitas. He had money, and was ripe for an investment. At that time, Guerrero was performing at a nightclub on North Broadway, run by the owner and his wife, who remain unnamed in his book. One day, the club owner proposed a business deal: create a 50/50 partnership to launch a new nightclub together. Though he had always considered himself “a lousy businessman,” Guerrero says he trusted the couple, “who treated me like their son.” He took the deal, so they scouted a location in East LA, and launched the first nightclub, called Lalo Guerrero’s.

In 1957, Guerrero was between novelty hits, post-Pancho Lopez and pre-Las Ardillitas. He had money, and was ripe for an investment. At that time, Guerrero was performing at a nightclub on North Broadway, run by the owner and his wife, who remain unnamed in his book. One day, the club owner proposed a business deal: create a 50/50 partnership to launch a new nightclub together. Though he had always considered himself “a lousy businessman,” Guerrero says he trusted the couple, “who treated me like their son.” He took the deal, so they scouted a location in East LA, and launched the first nightclub, called Lalo Guerrero’s.

The grand opening was announced with Hollywood-style searchlights illuminating the night sky. The club was an immediate hit, packed with people and flush with cash from the first night.

The business honeymoon did not last long, however. Guerrero claims his partners turned from nice to nasty; they “got greedy” and tried to force him out. On one occasion in the office, he claims his partner pulled a gun on him. He was “frothing at the mouth like a made dog,” Guerrero recalls, accusing him of trying to take over the club and threatening, “I’ll kill you first.”

The partner wasn’t totally crazy. Before a shot was fired, he offered to buy out his stunned partner’s share. “Sometimes I have trouble making decisions, but this was not one of those times,” recalls Guerrero, adding that he agreed to accept roughly the amount he had invested. “I just wanted out of there with my skin intact.”

Guerrero moved with his band “down the street” to the Paramount Ballroom, where he had frequently played before. And his fans followed. Without its star attraction, his ex-partner’s club steadily lost business, and was eventually sold.

“I knew what the people wanted, who the people wanted,” Guerrero writes, “and I was it.”

Guerrero soon got a second chance to run his old nightclub, which had come under new management but was still struggling. The new owners asked him to come back and work for them, but Guerrero made a counter-offer. He bought them out, took the club over, and renamed it simply Lalo’s. Searchlights once again announced the club’s rebirth at the same location, the corner of Marianna and Brooklyn (now Cesar Chavez Avenue) in East LA. The grand re-opening came on October 27, 1960. This time, Guerrero and his wife Margaret would run the lucrative business.

For more than a decade, Lalo’s became a mecca for Latin music, and Chicano culture, in East Los Angeles. One wall of the venue featured a mural of Guerrero’s characters – Pancho Lopez, Las Ardillitas, the little “Marciano” – painted by the late Carlos Almaraz, the pioneering Chicano artist who was a lifelong friend of Guerrero’s son, Dan. The cartoon collage is considered Almaraz’s first commission, although there are no existing images of the work. (The autobiographical, one-man play by Dan Guerrero, “Gaytino!” focuses on both his father and the painter as key figures in his life.)

On stage at the club, Guerrero brought in big-name acts from Mexico, including Jose Jose, Mariachi Vargas de Tecalitlán, El Piporro and Luis Arcaraz. In the audience, celebrities such as singer Tito Guizar and members of Los Panchos would drop by when they were in town.

Guerrero recalls it as a simple but classy place, with men wearing suits and ties and women in their finest evening attire. At times, it felt like a house party, with fans making requests and dedicating songs to their sweethearts. Guerrero’s tight band, including some of the original Cinco Lobos, would delight the dancers with whatever rhythm moved them at the moment – mambo, bolero, cha cha cha, polka, swing, or rock. And they could play the latest hits, hot off the radio.

Lalo’s also had a family feel. Many patrons knew one another (or “at least they did by the end of the evening.”). The club was like a community unto itself, where people met and married and later returned to share their stories with Lalo, the ever-gracious host. His own parents celebrated their 60th wedding anniversary there.

On Sundays it was an all-day fiesta, starting with a traditional tardeada at 3 p.m., broadcast for the first hour on radio, then ending with Lalo’s traditional sign-off theme at midnight, “Nuestro Amor’ (Our Love). The band was beat by then, but the dancers always wanted more.

“It was a party that went on and on for twelve years, “ Guerrero recalls.

But the constant partying took a personal toll. A reckless infidelity cost Guerrero his marriage.

Guerrero confesses that he had an affair with a woman (“this attractive girl”) in Fresno, while on tour. He claims the female fan later followed him to Los Angeles, and pursued him to the point of what he called stalking. When he’d try to get rid of her, he says she’d get emotional and create a scene.

Finally, the stalking stopped. After months of silence, Guerrero writes, he got a court summons in the mail. The woman had filed a paternity suit, and he could no longer hide the affair from his wife. Guerrero says he challenged the suit in court, “fought as hard as I could and spent as much as (required) for the lawyers and the fees.” But he lost, both the case and his marriage.

“All during the trial and the divorce proceedings, I continued to perform at my club, night after night,” he recalls. “Every night I had a whole club full of happy people but, sooner or later, I had to go back to my empty apartment. I had never lived alone before. I was so lonely.”

Politics and Protests

During the 1960s, while running the nightclub, Guerrero continued to tour with his band, still following the farmworker trail through California, especially the central San Joaquin Valley. At venues around Bakersfield and Visalia, he noticed a young man who showed up for every dance. He’d come up to the bandstand and chat during breaks, offering tips on where to tour based on “the action in the fields and orchards.” To Guerrero he was “just one of the guys,” smart and friendly, but somewhat anonymous. The musician never imagined that fan would become famous one day.

“A few years later,” he writes, “everybody in California knew Cesar Chavez.”

Because of his touring along farmworker routes, Guerrero soon found himself in the middle of one of the major labor movements of the 20th century, the fight to unionize agricultural workers led by Chavez and his UFW. In 1968, the movement spread from farm towns to major cities when student activists and others joined to support the UFW’s grape boycott.

During that time, Guerrero lent his support as a performer. He participated in union fundraisers and wrote “El Corrido de Delano,” a ballad about the birth and mission of the union. The Frontera Collection’s version was released on Discos Colonial, with the backing of El Conjunto Arellano, a norteño band with mariachi-style horn accents.

In those days, Guerrero also crossed paths in the fields with a fellow performer who would become key to cementing his legacy forever. Luis Valdez was also a young Chavez supporter who founded a grassroots theater group, El Teatro Campesino, that spotlighted labor issues through short, satirical skits performed on the back of flatbed trucks in the fields. Valdez, of course, would go on to use Guerrero’s music in his famous play “Zoot Suit,” almost two decades later.

Guerrero also used the corrido format to document a massive anti-war rally held in Los Angeles in the summer of 1970. In his “La Tragedia del 29 de Agosto,” Guerrero gives a powerful, passionate account of the Chicano Moratorium March in East L.A., which led to widespread rioting and the death of pioneering Mexican-American journalist Ruben Salazar. During the riots, Salazar was struck and killed by a tear-gas canister fired by an L.A. County Sheriff’s Deputy, in an incident that remains controversial to this day.

Guerrero opens the song by setting the scene, like most corridos. But he lets the listener know this one is personal because the tragedy hit close to home, “en el barrio junto a mi casa” (in the barrio near my house). Guerrero goes on to cite the protestor’s grievances, noting that Mexican-American soldiers made up a disproportionate number of war casualties (“mas del 23 por ciento, una proporción severa”).

When he gives voice to the demonstrators’ rage, Guerrero sings in a deep, guttural growl, full of outrage.

Cuando vino la policía

La violencia se desató.

El coraje de mi raza, luego se desenlazó.

Por los años de injusticia,

El odio se derramó.

Y como huracán furioso,

Su barrio lo destrozó.

The East L.A. protest was a defining moment for the emerging, socially conscious generation of Chicanos. Caught in the riot that day was a young musician named Louie Pérez, who would go on to form the legendary East L.A. band Los Lobos, along with his Garfield High School classmate David Hidalgo and two other friends from the neighborhood, Conrad Lozano and Cesar Rosas.

“They knew me and they admired me from the time they were real young kids,” Guerrero writes.

When they were starting off, the future Lobos would use Lalo’s nightclub as a rehearsal hall during the day. There was also a personal connection to the young band: Rosas, a singer, songwriter and guitarist, was the nephew of David Lopez, one of Guerrero’s original Cinco Lobos.

Those barrio relationships would pay off big time a quarter century later. As we shall see, Lalo and Los Lobos would one day re-unite and win a Grammy nomination together.

Guerrero sold his club in 1972, after 12 years. He suffered other personal losses shortly thereafter. His father died that same year, at age 87. His beloved mother passed away two years later at 85.

Yet, in the midst of middle age, Guerrero was about to open new chapters in his personal life and professional career.

Just before closing his club, Guerrero met and married Lidia de la Garza, a Los Angeles factory worker who was an occasional patron at Lalo’s. He describes her as “tall, slender, young and pretty.” Lidia also had two children, Jose and Patricia, whom Guerrero adopted and raised as his own.

After selling his club, Guerrero planned to return to Tucson to open his own restaurant. He found a location to rent, and ordered a large neon sign for the new business. But it never opened because he discovered, too late, that the owner, who was Mormon, would not allow a liquor license. (“What kind of Mexican restaurant doesn’t have beer?”) So he lost his initial investment, and decided to return to Los Angeles, with “my tail between my legs.”

At 57, he felt like a flop.

But on his way back, luck again crossed his path. Passing through Palm Springs, he learned that an old friend, singer Gloria Becker from Discos Real, was trying to reach him. Becker was now a booking agent and had a job offer. A new restaurant was opening in nearby Rancho Mirage and the agent thought Guerrero would be ideal as their entertainer.

That standing engagement at Las Casuelas Nuevas would last 24 years.

Guerrero and his new family settled in Palm Springs, and he became a fixture at the restaurant, sitting on a stool near the bar, playing his guitar under a solo spotlight. Guerrero became friendly with the regular customers, including Hollywood celebrities Frank Sinatra, Dinah Shore, Jack Benny, Red Skelton, Bette Midler, and Don Rickles. In his biography, Guerrero details the special relationship he developed with Sinatra at the restaurant over the years, including the time he sang “Las Mañanitas” for the Chairman of the Board’s 81st birthday in 1996.

Guerrero and his new family settled in Palm Springs, and he became a fixture at the restaurant, sitting on a stool near the bar, playing his guitar under a solo spotlight. Guerrero became friendly with the regular customers, including Hollywood celebrities Frank Sinatra, Dinah Shore, Jack Benny, Red Skelton, Bette Midler, and Don Rickles. In his biography, Guerrero details the special relationship he developed with Sinatra at the restaurant over the years, including the time he sang “Las Mañanitas” for the Chairman of the Board’s 81st birthday in 1996.

Guerrero also kept busy outside the restaurant.

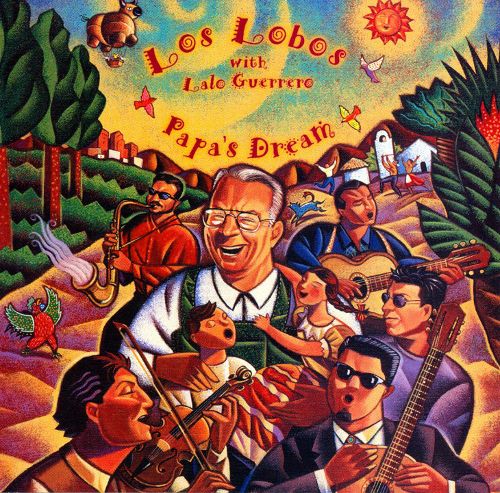

In 1994, he was reunited with Los Lobos for a bilingual children’s album titled “Papa’s Dream,” about a man who imagines taking his children and grandchildren on a trip to Mexico to celebrate his 80th birthday, flying on the Wooly Bully blimp. Producer Lieb Ostrow asked Los Lobos to recommend someone who could play the grandfather, and they didn’t hesitate: “We know just the man: Lalo Guerrero.”

The children are played by members of Los Lobos and the grandchildren by the Children’s Coro of Los Cenzontles, a Mexican folkloric group from the San Francisco Bay Area led by Eugene Rodriguez, who conducted and contributed lyrics, along with Guerrero. The album, released on the Music for Little People label and distributed by Warner Bros. Records, earned Guerrero his first Grammy nomination in 1995, for Best Musical Album for Children.

By then, Guerrero had long overcome the criticism generated by the alleged stereotyping in his “Pancho Lopez” parody. His rousing activist songs, combined with the endorsement of respected Chicano figures such as Luis Valdez and Los Lobos, helped burnish his reputation as a Chicano icon. Culture Clash, the satirical Chicano theater trio, also featured Guerrero in 1993 on their TV show, nationally syndicated by Fox. Introduced as “a mentor and one of our elders,” Guerrero performed his parody “No Chicanos on TV” to the delight of the live audience.

A year earlier, Guerrero was the subject of a tribute held in Palm Desert, one of many honors he received in his later years. The show, “Lalo & Amigos Tribute Concert,” was held Oct. 11, 1992, at the McCallum Theatre in Palm Desert; it featured a constellation of Chicano stars, including Cheech Marin, Paul Rodriguez, Little Joe, Gilberto Valenzuela, Mercedes Castro, Don Tosti, Daniel Valdez, and Culture Clash.

Speaking at the event was that one fan who, as a young man, used to show up at all the dances in the San Joaquin Valley. “Lalo has chronicled the events of the Hispanic in this country a lot better than anyone," said the speaker, César Chávez.

The Pinnacle in Paris

Perhaps the pinnacle of Guerrero’s career came in 1998, when, at age 81, he was invited to participate in a three-day American music festival in Paris, at La Cité de la Musique. The trip was documented in the Los Angeles Times by writer Michael Quintanilla, who described Guerrero as “the toast of Paris,” celebrated by fans wherever he went in the City of Lights. Guerrero was accompanied on the trip by his sons Mark, who served as the show’s musical director, and Dan. The band featured Mark on guitar and vocals, Lorenzo Martinez on guitarron, as well drummers Max Baca (Texmaniacs, Super Seven) and David Jimenez, members of another featured band led by Tex-Mex accordion legend Flaco Jimenez. (David is Flaco’s son.)

Perhaps the pinnacle of Guerrero’s career came in 1998, when, at age 81, he was invited to participate in a three-day American music festival in Paris, at La Cité de la Musique. The trip was documented in the Los Angeles Times by writer Michael Quintanilla, who described Guerrero as “the toast of Paris,” celebrated by fans wherever he went in the City of Lights. Guerrero was accompanied on the trip by his sons Mark, who served as the show’s musical director, and Dan. The band featured Mark on guitar and vocals, Lorenzo Martinez on guitarron, as well drummers Max Baca (Texmaniacs, Super Seven) and David Jimenez, members of another featured band led by Tex-Mex accordion legend Flaco Jimenez. (David is Flaco’s son.)

Flaco joined Lalo on stage for a rousing climax to the festival that received a long, standing ovation. According to the Times report, the appreciative Paris fans jumped to their feet shouting “Bravo!” Lalo, taking bows and blowing kisses, responded with shouts of “Viva Mexico! Viva America! Viva Paris! I'm 81 years old, and I love Paris! Viva yo! Viva vous!"

“With that, he exits, overjoyed,” reports Quintanilla. “His sons can't wait to hug him, and when they do, Lalo unleashes a flood of emotion.”

At that point, Guerrero still had another seven years to live. Sadly, he developed prostate cancer and dementia and spent his final months in an assisted living home in Rancho Mirage, where he passed away in 2005. The Father of Chicano Music kept working, and receiving prestigious honors, almost to the end.

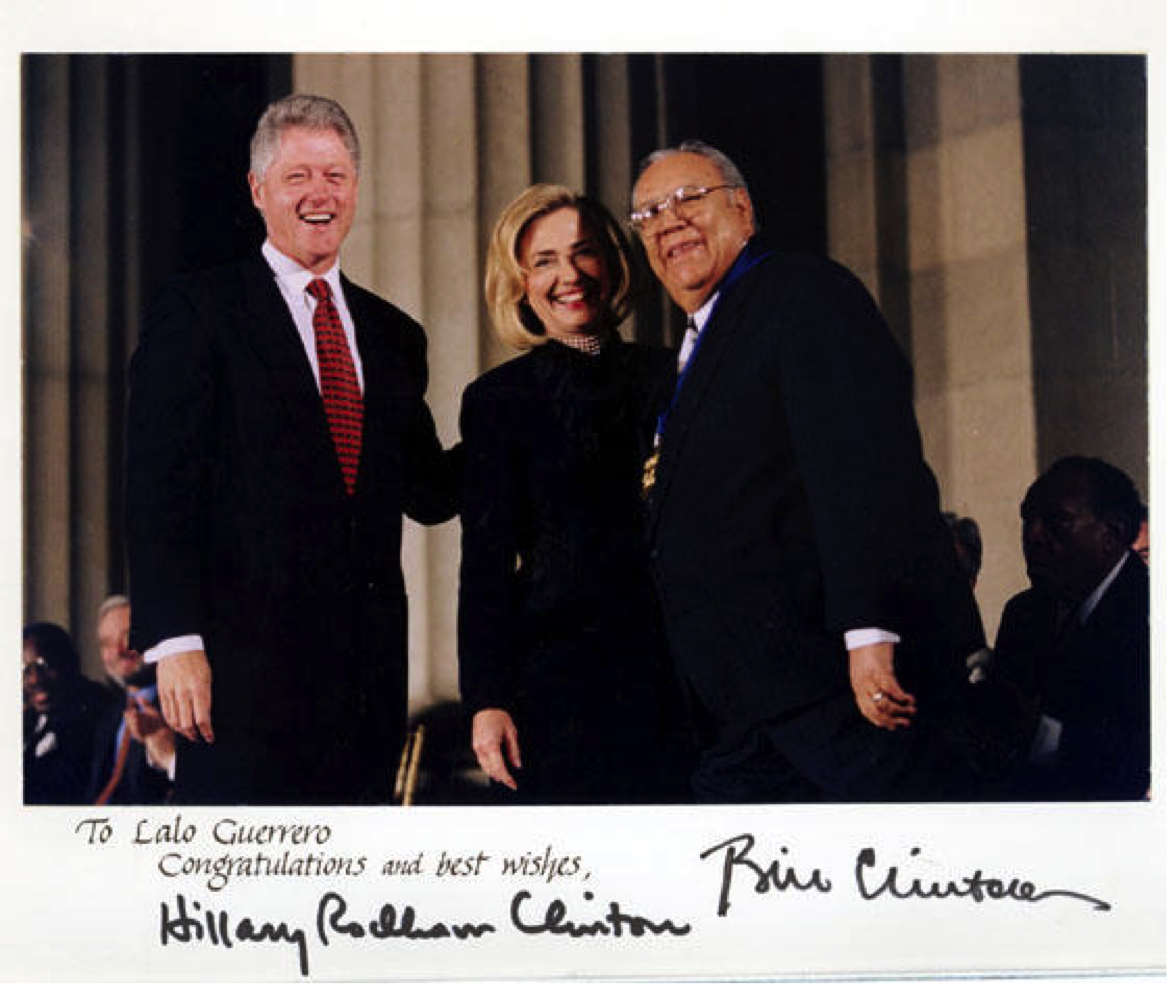

In 1997, he became the first Chicano to receive the National Medal of Arts, the nations most prestigious honor for artistic achievement, presented by Bill and Hillary Clinton at the White House. In 1991, Guerrero received the NEA’s National Heritage Fellowship, presented by President George H. W. Bush. On that occasion, Guerrero performed his corrido about the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy; he also participated in a panel (moderated by journalist Charles Kuralt) along with other honorees, including blues legend B.B. King, which the life-long blues fan considered “an incredible thrill.”

Among his many other honors, Guerrero was named a National Folk Treasure by the Smithsonian Institution (1980), was inducted into the Tejano Music Hall of Fame (1992), received an Alma Award (1998), and a Golden Palm Star on the Palm Springs Walk of Stars (1994).

Among his many other honors, Guerrero was named a National Folk Treasure by the Smithsonian Institution (1980), was inducted into the Tejano Music Hall of Fame (1992), received an Alma Award (1998), and a Golden Palm Star on the Palm Springs Walk of Stars (1994).

All those honors are hard to top. But few other Chicano artists can say they also have had a street and a music school named after them, and a statue erected in their honor.

The Lalo Guerrero School of Music was founded as an after-school program in 1999, part of the “Art in the Park” organization sponsored by the City of Los Angeles and located at Arroyo Seco Park, where Guerrero would often teach guitar to young students.

In Cathedral City, where Guerrero lived out his final years, the street that runs along the civic center in the heart of downtown was renamed Avenida Lalo Guerrero, placing his name on all the city’s official documents and correspondence. And two years ago, the city commissioned the Lalo Guerrero Sculpture, a six-foot bronze statue of the troubadour playing his guitar, located in Town Square Park across from City Hall. The sculpture was unveiled on Dec. 15, 2016, on the eve of what would have been the musician’s 100th birthday.

Many of Guerrero’s awards have been archived in a special collection at the University of California, Santa Barbara, along with dozens of documents, photographs, interviews, press clips and original recordings. The Lalo Guerrero Collection is part of the California Ethnic and Multicultural Archives of the UCSB Library. Copies of many of these items are available at the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center library as part of its Dan Guerrero Research Collection, 1930-2003.

Guerrero’s final studio recordings were made in collaboration with famed guitarist and producer Ry Cooder for the album Chavez Ravine. The work, released by Nonesuch, is a musical narrative about the displacement of Mexican-American residents from a poor neighborhood where Dodger Stadium now stands. Guerrero contributed three songs to the album, including his nostalgic “Barrio Viejo,” about his beloved Tucson community.

Cooder, along with Linda Ronstadt, Edward James Olmos, Cheech Marin and other celebrities, was featured in a television documentary about the late singer, Lalo Guerrero: The Original Chicano, which aired nationally on PBS stations in 2006. It was co-produced by his son, Dan, and filmmaker Nancy De Los Santos.