Singer Eva Garza launched her singing career as a teenager in San Antonio, Texas, and emerged as one of the few Mexican-American artists to gain international acclaim throughout the Americas. An accomplished and seductive interpreter of the romantic bolero, she collaborated during the 1940s and ’50s with top figures in the field, including Mexico’s Agustin Lara and Cuba’s Isolina Carrillo.

In a tribute published upon Garza’s death in 1966, the Mexico City newspaper Excelsior dubbed her “one of the 10 best singers in México.” The paper’s posthumous homage noted that Garza “had distinguished herself from a very young age for the warm timber of her voice, her emotional expressiveness and her great versatility, since she was equally capable of singing romantic boleros, spirited corridos and ranchers, as well tropical music and contemporary tunes.”

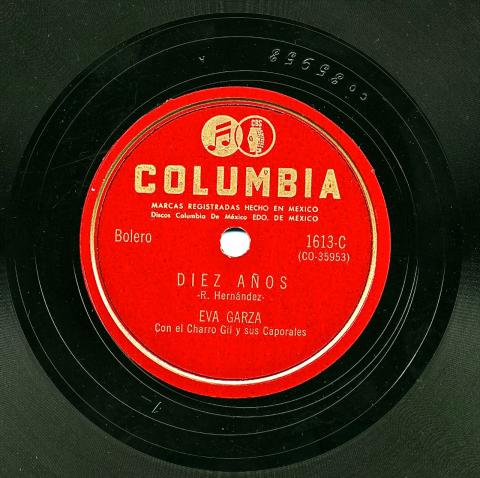

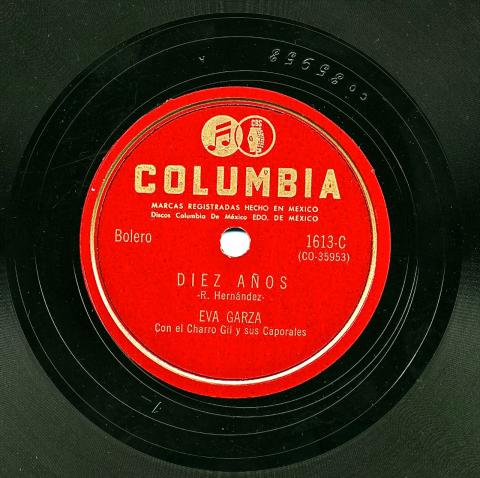

Garza recorded for several major labels, including

Columbia Records, which issued her earliest recordings in New York where she had relocated to pursue her career. Though she died less than a year before reaching her 50th birthday, she left a deep and rich recorded catalog. Garza ranks No. 32 on the list of the top 50 most-recorded performers in the Frontera Collection, with

154 recordings in the archive. Singer Chelo Silva, a fellow Texan also known for boleros, ranks higher in the archive at No. 6, possibly because Silva hailed from the border town of Brownsville and kept a more regional profile on Tex-Mex labels, a Frontera specialty.

For all her success and fame, relatively little has been published about Garza’s life and successful career, at least until recently. “I was continually amazed that her story has not circulated more,” wrote Deborah R. Vargas, who researched Garza’s work for

her book,

Dissonant Divas in Chicana Music: The Limits of la Onda, published in 2012. The author traced Garza’s career path to Havana, an important capitol of the bolero, where Garza had become “one of the biggest artists on Cuban radio” during the mid-to-late 1940s. And yet, the writer notes, the singer did not get the same recognition on her own home turf back in Texas.

“For much too long, Chicana musical contributions such as Garza’s have been too highly overlooked, misplaced, and under-analyzed,” wrote Vargas in a short

essay about the singer, titled “Eva Garza: From El Barrio To Boleros.” From a feminist perspective, the writer adds, this biographical neglect relegates Garza, and other Chicana artists like her, to remain “in the shadows” of dominant historical narratives.

Eva Garza was born on May 11, 1917, in the working-class, Westside barrio of San Antonio. She was the third of seven children raised in the humble household of Cenobia B. Ramírez and Procopio V. Garza, who ran a barbershop on Commerce Street. Described as a friendly and precocious girl, Garza sang at church functions and at private parties, and never missed a chance to sing around the house, especially American standards she heard on the radio. “She sang all the time. She had a style of her own,” her sister, Tina Moore, told the San Antonio Express-News in 2013 on the occasion of an

Eva Garza retrospective organized at San Antonio’s Esperanza Peace and Justice Center.

As a student at Lanier High School, Garza also excelled at sports. Her accomplishments as an all-star athlete in basketball and baseball were documented in the local press during the 1930s. The dynamic newspaper photos of Garza in her athletic uniforms – spotlighting a star athlete who was also female and Mexican-American – inspired her peers in an era when segregation and sexism were rampant.

Garza’s music career got a start on local radio, an important vehicle for exposing new talent at the time. After hearing her sing an opera, Garza’s high school music teacher was so impressed that she ushered her star student to a radio audition, doing a duet with a boy on “Indian Love Call” and “Sweet Mystery of Life,” according to a brief bio by Clayton T. Shorkey on

The Handbook of Texas Online.

Soon, Garza started winning vocal competitions. However, her strict parents didn’t entirely approve of her music-career ambitions, since most performance venues were considered inappropriate for “respectable” young women. Still, at a time when other girls her age were getting their quinceañeras, Garza insisted on finding an audience for her vocal skills. She entered an amateur contest sponsored by the Monte Carlo Brewery at San Antonio’s Texas Theatre, taking home $500 for 2nd place with her rendition of “I’m in the Mood for Love.” In another contest, at the local Zaragoza Theatre, she went home with a piano as a prize.

The radio exposure eventually led to more steady gigs, and her first recording contract.

From 1932-34, she was heard regularly on radio KABC, then housed at the Texas Theatre, and she was regularly heard on one of San Antonio’s most popular programs, “La Hora Anahuac.” She also began performing at the Nacional Theatre, along with vaudeville acts that were popular with Mexican audiences at the time, especially

Netty y Jesús and Don Suave.

When she was 19, Garza made her first recordings for Bluebird Records, one of the national labels that would set up mobile studios at local hotels and offer local artists a chance to record. During her first sessions at San Antonio’s Texas Hotel on October 23, 1936, Garza did numbers in a mix of styles, rumba, son, and bolero. The sides included

“La Jaibera” (The Crab-Seller),

“Qué Me Importa” (What Do I Care?),

“Calientito” (Kinda Hot),

“Cosquillas” (Tickles), and

“Cachita,” the popular, playful guaracha by Puerto Rican composer Rafael Hernandez.

Garza’s “big break came in 1937 when she auditioned for Sally Rand,” writes Shorkey. Rand, a former silent film actress, had caused a sensation with her “fan dance,” a burlesque act considered risqué at the time. Eva was hired for her “strong voice,” Shorkey notes, and she toured with Rand throughout North America for six months. When the tour ended, the singer returned home and soon went out on her own, launching Eva Garza and Her Troupe.

Garza then hit the road, with a touring schedule that would take her throughout Mexico, Central and South America, as well as Cuba and the Caribbean. It was during one of those tour stops in Juarez, Mexico, that Garza met the man who would become her first husband. On December 30, 1939, she married

Felipe “El Charro” Gil, whose Trio Los Caporales was a precursor of the wildly popular Trio Los Panchos that featured his brother, Alfredo Gil. After a hometown Texas wedding, the couple settled in New York City. Garza performed as a soloist with different ensembles, but she also performed with her husband, as on this recording of

“Diez Años,” an aching bolero by Rafael Hernandez, backed by “Eso Si…Eso No…,” a spirited tune written by Gil and backed by his Caporales.

From the beginning, there were strains in the relationship that would ultimately dissolve the marriage. “Much to Gil’s dissatisfaction, Garza would keep her last name,” writes Vargas in her book. “Neither Gil nor many of the promoters Garza came across thought it was appropriate that she travel solo as a married woman and so eventually Gil would reduce his time as musician and devote most of his efforts to managing her career.”

And her career took off. In New York, Garza made her first recordings for Columbia Records and had her first hits,

“Sabor de Engaño” and

“Celosa.” (She radically slows the rhythm on this later

45-rpm version of “Sabor de Engaño,’ also on Columbia, backed by Pepe Jaramillo on piano.) During the mid-1940s, Garza “gained a vast new audience” through her appearances on Viva America, broadcast by the CBS radio network. The government-sponsored program was part of the so-called “good neighbor” policy, an effort by the United States to foster positive cultural relations throughout the Americas, while stemming Nazi influence in the hemisphere. The show was also broadcast over armed forces radio during World War II, earning Garza the nickname among the troops of “Sweetheart of the Americas.”

That voice that came over the airwaves hit an emotional chord with listeners. “Garza’s singing voice was heartfelt and cavernous,” writes Vargas. “When she sang she transferred emotions and tales from her core, grasping for deep exhalations of sentiment. Especially in rancheros and boleros, one could note her tendency to weep impassioned feelings into a song. Her voice tapped into an inner core filled with experiences, memories, departures, and returns.”

Garza first visited Havana in 1946, quickly becoming one of the biggest artists on Cuban radio. She also performed at legendary nightclubs, such as the Tropicana, and appeared on one of the most popular music shows of the day, “Duelo de Pianos,” along with Agustín Lara and Consuelo Velasquez.

The singer’s growing popularity in Cuba and Latin America also got a boost from

her recordings on Seeco Records, a leading, New York-based independent label for Latin music at the time. Garza’s early 78-rpm recordings are especially valuable as representations of her early work, notes Vargas, “because much archived material of taped television and radio programs has been lost or destroyed since the post-revolutionary period in Cuba.”

Garza moved to Mexico City in 1949, establishing herself there as one of the biggest singing stars during the early 1950s. She became a regular on the capital’s influential radio station XEW, sharing star-studded lineups with the biggest names of the day, such as Pedro Infante, Pedro Vargas, Javier Solis, and Jorge Negrete. And in the studio, she recorded songs by the top composer’s of a golden era in Mexican pop music, songwriters such as Agustín Lara, Gonzalo Curiel, and Joaquín Pardavé. Overall, Garza recorded more than 200 tracks for major labels, including Decca, RCA, Columbia and Musart. Among her other big hits from this period are

“Sin Motivo,” “Frio en el Alma,” and

“La Última Noche.”

During this period in Mexico, Garza also made more than 20 motion pictures, co-starring with marquee names, such as Toña La Negra (Amor Vendido, 1951), Sara Montiel (Cárcel de Mujeres, 1951), and Luis Arcaráz (Acapulco, 1952).

In 1958, she starred in one of her last films, appropriately titled Bolero Inmortal (Eternal Bolero). “Garza plays Lucha Medina, a washed-up bolero singer whose sexual appeal has passed and who is replaced by a younger singer,” writes Vargas. “Divorced and alone, Lucha sees no dignified way to end her career, so, in dramatic bolero style, she decides to take her own life.”

Garza’s real life ended sadly and prematurely, but not nearly as tragically. In 1953, she divorced “El Charro” Gil, with whom she had had three children, including a son, Felipe Gil, a successful singer and songwriter in his own right, also known by the stage name

Fabricio. (Felipe Gil, the younger, made

news in 2014 when, at age 73, he announced he was transgender and taking the name Felicia Garza, adopting his mother’s surname.) In 1965, Eva Garza remarried, this time to Argentine artist Abel Reynosa, with whom she moved to Buenos Aires.

Garza continued to record and tour through another year, unaware it would be her last. Columbia Records invited her to return to Mexico to record a comeback album,

Vuelve Eva Garza – Mexican Encore, for which she re-recorded some of her biggest hits, including the tango “Arrepentido.” Later, she went on tour again throughout the southwest, including an appearance in Los Angeles. During a stop in Tucson, Arizona, she was diagnosed with double pneumonia and died there on November 1, 1966. The singer, who had put so much heart into her songs, died of a bad heart, weakened from the rheumatic fever she had suffered as a child. She was 49.

According to her wishes, Garza’s remains were returned to Mexico City for burial. Although the bolero had made her famous throughout the world, notes Vargas, that fame also came to displace her from her Mexican-American roots. “Rather than returning her body to be buried in the birthplace of San Antonio,” Vargas writes, “she had given her son Felipe specific instructions that her final ‘home’ was to be in Mexico City among the star-studded cast of the Panteón Jardín, the Mexican cemetery of musical and cinema stars.”

Eva Garza is certainly not forgotten in San Antonio. She is one of three hometown Tejana artists (along with Lydia Mendoza and Rosita Fernández) prominently featured in a major mural commissioned in 2008 to honor San Antonio musicians. In 2013, she was inducted into the Tejano R.O.O.T.S. (Remembering Our Own Tejano Stars) Hall of Fame, joining other Tejano music pioneers such as Narciso Martinez.

-Agustín Gurza

Add Your Note