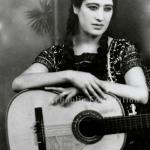

Artist Biography: Lucha Reyes (1906 –1944)

Me llaman La Tequilera como si fuera de pila,

Porque a mí me bautizaron con un trago de tequila.

Lucha Reyes, an aspiring opera singer who became an accidental star in the blossoming mariachi music scene of 1930s Mexico, is considered a pioneer of the brash and defiant singing style that would set a standard for ranchera singers for decades to come. Reyes not only broke barriers for women in the traditionally male genre, she revolutionized the entire mariachi world by making the lead vocalist the center of attention in the folkloric ensemble.

Born just four years before the outbreak of the Mexican Revolution, Reyes rode the subsequent wave of nationalism that sparked a renaissance of indigenous art in painting, literature, film, and music. The commanding and iconoclastic singer came into her own as a solo artist just as this movement in the arts gained national momentum, giving her the opportunity to rub shoulders with other creative luminaries of the day, such as Diego Rivera and, while in Los Angeles, muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros.

Reyes demolished social mores by flaunting female independence. She allegedly engaged in bisexual relationships and commandeered the once exclusively male privilege of drinking in

public, mixing tequila and passion as part of her act. In legend, she became identified with the star-crossed, broken-hearted, hard-drinking heroine of one of her last hit songs,

“La Tequilera.” Reyes’ singing style, known as “estilo bravío,” combines forceful vocals with a defiant stance and a brash attitude on stage. “No singer could be the same after watching a performance by Lucha Reyes,” declared the respected Mexican magazine

Proceso in a

1993 article assessing her legacy.

Sergio de la Mora, associate professor of Chicana/o studies at UC Davis, calls Reyes “a modern and brilliant woman who was ahead of her time.”

Despite Reyes’s stature as a pioneering and influential artist, many of the details of her biography are clouded in contradictions and shrouded in celebrity gossip. Her reputation for sexual adventures, alcoholic binges, and personal conflicts, especially with her mother, has become the stuff of myth and legend. In all the sources reviewed for this biography, only one provides a defense of the singer’s character–

a statement on a now inactive blog by her close friend and collaborator Nancy Torres, “La Potranquita,” that dismisses reports of Reyes’s dissolute lifestyle.

One thing is sure: Reyes was a deeply troubled artist. In her short 38 years of life, she twice lost her voice due to illness, once lost a baby and became infertile, and never found happiness in her three marriages. She committed suicide in 1944, during a low point in her career in what some describe as a deep depression.

Reyes, who would have turned 100 this year, has been the subject of occasional attempts, by journalists and researchers, to restore her artistic reputation and vindicate her legacy. In Los Angeles in recent years, admirers successfully pushed to have a

statue of the singer erected in 2009 at Mariachi Plaza in Boyle Heights, where

a street was later named for her as well. Meanwhile, academics in California have worked to establish her place in Mexican history as a feminist icon.

“Before the bravío style of Reyes, traditionalists thought that women should only sing in private, at get-togethers with family or friends, at church or while they did their daily chores,” states Antonia Garcia-Orozco, associate professor of Chicano and Latino studies at Cal State, Long Beach, adding that only men or prostitutes sang rancheras or corridos. “After Reyes, it was more acceptable for women to sing corridos or ranchera songs in private or in public, without automatic or permanent social stigma.”

Lucha Reyes was born on May 23, 1906, in Guadalajara, Jalisco, the Mexican state considered the cradle of mariachi music. Her real name was María de Luz Flores Aceves, the daughter of Victoria Acev

es who, according to her own account, later served as a soldadera in the Mexican Revolution of 1910. The singer’s paternal parentage is less certain. Several sources, including L.A.-based biographer

Nazib Fauntel, identify Reyes’ father as Miguel Angel Flores, a revolutionary general who was to become governor of Sinaloa. Others, however, claim Reyes’s father was actually

a local cantina owner, or alternatively,

a wealthy landholder who sold charro hats in Guadalajara. Whatever the case, her real father was out of her life at an early age, and the girl adopted the surname of her stepfather, who raised her through her teen years.

Reyes’s mother was a presence throughout her life, but her background is also shaded by rumors. Some say Reyes’s mother was a madam, and

Proceso even claimed – ironically, in that same article about salvaging the Reyes legacy – that the singer was “born in a brothel,” but offered no attribution. In her own exhaustively researched article about the singer’s life and career, “

Lucha Reyes la Reina del estilo Bravío,” Garcia-Orozco dismisses the reports as “malevolent mythology.”

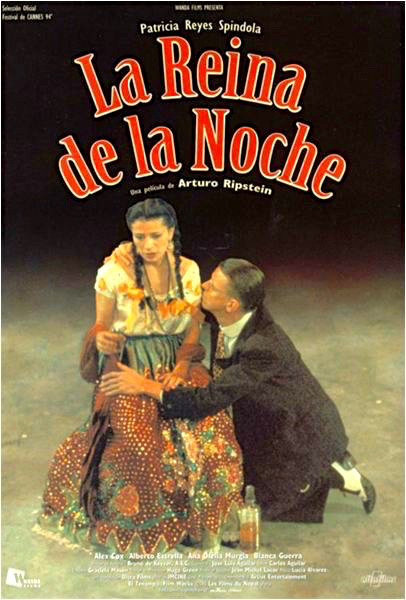

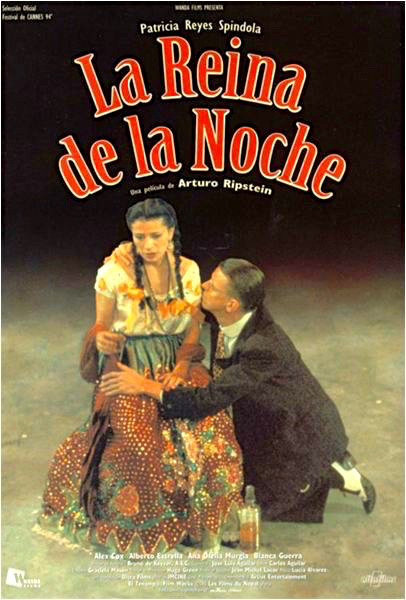

The negative portrayals, the writer adds, were perpetuated in part by scenes in the controversial 1994 film

La Reina de la Noche (The Queen of the Night), a novelized biopic by director Arturo Ripstein, that was nominated for the Palme D’Or at the Cannes Film Festival. De la Mora also

takes issue with the way Reyes is depicted in the film as a “fragile, suicidal alcoholic” and a “tragic and self-destructive victim.” Later, feminist writers such as Alma Velasco, in her novelized biography

Me Llaman La Tequilera, would demystify that pathetic version of Reyes, whom de la Mora calls an “enigmatic, ambiguous, contradictory and complex figure.”

What is not disputed is that Reyes’ vocal talents were recognized at an early age. The girl would sing at home in a beautiful voice that showed operatic potential. However, at around five years of age, she suffered an illness, some say typhus, which caused her to lose her voice for a year, presaging a future, fateful illness as an adult that also left her mute. When the girl finally recovered her voice, she began a singing career, but had to drop out of school to help support her family.

By the time she turned 10, Reyes had moved to Mexico City with her family, setting up residence in Tepito, an infamous neighborhood near the city’s historic center known for its violent crime and street hustlers. Reyes joined the church choir at Iglesia del Carmen and soon was taking lessons to sing zarzuelas. Reyes was barely a teenager when she started performing at a carpa, or traveling tent show, located at the nearby Plaza San Sebastián. It was here, in this vaudeville environment, that she met Torres, a well-known Spanish singer and actress nicknamed La Potranquita, who would become her patron, friend, and collaborator.

Details about this early stage in her career, not found elsewhere, are reported in a dormant blog, “Lucha Reyes: Pionera de la Musica Ranchera,” that is now archived

here. In a section

titled

Primeras Luchas, the blog notes that Reyes was 15 when she entered a contest at the carpa, one of the first in Mexico City to present opera. She sang “Un viejo amor,” backed by a Jewish-German pianist named Isaac Goldenberg, who later became her teacher. Her operatic vocal style got an ovation and “she was hired right then and there.” Performing as Elvira Reyes, the young soprano had the opportunity to sing lead roles in such classical works as

Carmen,

Madama Butterfly, and

Pagliacci.

In 1920 or 1921, depending on sources, Reyes made her first trip to Los Angeles, to study voice and develop her skills as a soprano. Still in her early teens, the singer was accompanied on the trip by Torres, not by her mother. According to unnamed sources cited by

de la Mora, Reyes had moved to Los Angeles “to flee her mother with whom she did not get along.” Also citing anonymous sources, Garcia-Orozco says there were rumors that Reyes and Torres were romantically involved. .

Billed in L.A. as “the world’s youngest singer,” Reyes had been contracted for a U.S. tour by theater empresario

Romualdo Tirado Pozo, a stage and film actor who had come to Los Angeles from Spain a year or two earlier, accompanied by his family and a troupe of actors. Romualdo, who appeared in many Hollywood talkies, rented local movie theaters where he produced shows that featured everything from opera to zarzuelas and vaudeville for Latino audiences. At times, Reyes performed as a duo with La Potranquita.

It was during this period in Los Angeles that Reyes met and married her first husband, journalist and playwright Gabriel Navarro, who later worked for La Opinion, L.A.’s long-lived Spanish-language daily. The dissolution of that relationship, according to some sources, set Reyes on her course of psychic agony and alcoholism. Garcia-Orozco reports that Reyes was the victim of domestic violence, sparked when her husband learned of her lesbian affair with Torres. Reyes was pregnant and lost her baby after one such beating, and she became sterile. “The failure of this relationship had a drastic influence on Reyes,” Garcia-Orozco writes.

In 1924, Reyes separated from Navarro and returned to Mexico City, writes the author, “after having seen her reputation damaged in Los Angeles for having publicly aired her personal life.”

Torres herself adamantly refutes the accounts. “Reyes never behaved like a public drunk who stumbled on stage and made a scene, but rather she was ‘a lady’ of the fiesta,” Torres insists. “She had her problems, but never in public. I don’t think anyone could say that she caused this-or-that commotion (zafarrancho) at such-and-such a cabaret. She was very reserved in many ways. She could not be a mother, but that didn’t bother her at all. And she had absolutely no trace of lesbian.”

Back in Mexico, Reyes successfully resumed her career with appearances at major venues of the day, such as Teatro Lirico and Teatro Esperanza Iris, the latter named for the popular singer and actress who had it built in 1918. (Today, it has been restored to its original neo-classic grandeur and renamed

Teatro de La Ciudad Esperanza Iris.) Reyes was soon performing zarzuelas alongside Esperanza Iris herself, known as “the queen of the operettas.” In 1925, before Reyes turned 20, she joined a French burlesque show called “El Bataclán de París,” which had come to Mexico to perform. Reyes was reportedly billed under the pseudonym Lucianee Duvacell.

These were hard times for Reyes, writes Garcia-Orozco who refers to the Paris act as “a parody of the controversial French burlesque dance, the Can Can.” She also started singing rancheras intermittently, occasionally using the stage name that would stick, Lucha Reyes. Spotted and recruited by

José “Pepe” Campillo, a theater impresario at Teatro Lirico, Reyes became lead singer for the Trío Reyes-Ascencio, joined by sisters Blanca y Ofelia Ascencio. Garcia-Orozco suggests that Reyes was forced out of the trio after the sisters complained that she drank too much and was often late, not to mention the fact that “one of the sisters competed with her for the (romantic) attention of the impresario.” Reyes left the trio in 1927, replaced by Julia Garnica in the new

Trío Garnica-Ascencio.

That same year, Reyes joined a tour headed to Europe, with bright hopes of emerging as a professional opera star who would return to Mexico and perform at Bellas Artes, the imposing art deco theater that was a mecca of Mexican culture. Although the tour proved to be disastrous, both financially and personally, Reyes would turn her misfortune into a new career chapter. Rather than being sunk by failure, she emerged a star.

Reyes had joined the tour as part of the Cuarteto Anahuac, led by Juan Nepomuceno Torreblanca of the Orquesta Típica Mexicana. For unknown reasons, the tour collapsed after arriving in Berlin, and the director is said to have abandoned his troupe and returned to Mexico. The stranded musicians worked at taverns and beer halls to earn enough money for the long voyage home. Eventually, they made it back on a cargo ship as “third-class

And yet, the European tour resulted in an important music milestone for Reyes. In Germany, she was able to make her first recordings, with Torreblanca and his orchestra. Her clear soprano can be heard on this rendition of “

Alma de Mujer,” one of eight recordings made by Polydor in Berlin, according to this archived blog page titled “

Sus Primeras Grabaciones.” The Frontera Collection has several of these early recordings on

a compilation album entitled

Lucha Reyes...Sus Primeras Grabaciones, Alemania 1927, Mexico 1936, reissued on the Documental label.

The tour also created a long-term problem for Reyes that marked a professional turning point. The singer had fallen ill while in Europe and, in an echo of her childhood illness, lost her

voice once again. Reyes returned to Mexico and was unable to sing, or

afónica, for about a year.

As legend has it, when Reyes recovered her voice it had changed from a pure soprano to a hoarse, breaking vocal no longer suited to classical styles. To continue her career as a singer, Reyes had no choice but to turn to the folkloric style of mariachi music that complemented her “new, husky voice.” From that point forward, Reyes embraced ranchera music in a full-throated, rousing style at a time when the revolution had breathed new life into all things Mexican.

“Upon recovering her voice, she was able to undertake, in a contralto voice with rough and gravely tones, the nascent urban ranchera song,” writes Yolanda Moreno Rivas in her book,

Historia de la Música Popular Mexicana. “Her personality and her neurosis would do the rest. She gave of her voice lavishly, to the point of ripping it. She wailed, cried, laughed and cursed. Overcoming critics who could not accept her lack of refinement, Lucha Reyes quickly came to symbolize and personify the bold and temperamental woman, Mexican style.”

Her career as a ranchera singer was relatively short, about 16 years from 1928 to her death in 1944. But her rise to stardom was dazzling. Reyes was soon the toast of the town and the darling of the Mexican literati, rubbing shoulders with creative peers from the revolutionary era, from Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo, to film actor and director Emilio “El Indio” Fernández, who was her compadre. In Los Angeles during the 1930s, Reyes performed

at popular Olvera Street restaurants La Golondrina Café and Café Caliente (now Paseo Inn), which featured after-hour nightclubs where regulars included Hollywood stars such as Humphrey Bogart, Rita Hayworth, and Orson Wells. During that time,

she befriended famed Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros who was working on his controversial Olvera Street mural,

America Tropical.

In the late 1920s, following her aborted European tour, Reyes teamed up with singers Jose “Pepe” Gutierrez and Felipe Enríquez, launching a new trio together called Mexico Lindo. Later, when Enriquez left the group, Reyes remained as a duo with Gutierrez, who was also a guitarist. They called themselves Los Trovadores Tapatíos (a reference to their Jalisco roots), and recorded for the Victor label in Mexico. The Frontera Collection includes one of their original 78s (

Victor 75194), with the songs “El Petate,” and “El Corrido Villista,” from the 1935 film

El Tesoro de Pancho Villa. On the label, she is identified as Luz – not yet Lucha – Reyes.

“Working as a duet gave Reyes stability: she was punctual, she stopped drinking, she took care of her voice and developed a style with which she would be immortalized as a soloist,” writes Garcia-Orozco.

In 1930, Reyes was invited to perform as a soloist at the inauguration of Mexico City radio station XEW, which would become a powerful force for promoting Mexican music throughout the 1930s and ’40s, a golden era for pop culture in the country. Soon she was hired to make regular appearances on the station, which called itself “La Voz de América desde México.” For her live radio performances, the station hired the top ensembles of the day, including Mariachi Tapatío de José Marmolejo and the Mariachi Vargas de Tecalitlán.

The popular radio broadcasts made Lucha Reyes a household name, earning her the title “La Reina de los Mariachis.” Also in 1930, according to Proceso, Reyes was contracted by promoter Frank Founce for a series of concerts at the Million Dollar Theatre in downtown Los Angeles. The shows were enthusiastically received, marking her successful ascent as an international star.

Four years later back in Mexico City, Reyes sang at the inaugural ceremonies for popular leftist President Lázaro Cárdenas, who consolidated the goals of the Mexican Revolution in national policy. Reyes performed the new president’s favorite song,

“Juan Colorado,” backed by the Mariachi Vargas. President Cardenas’s “affinity” for the singer and her bravío style, Garcia-Orozco notes, “gave cultural legitimacy to Reyes, to the mariachi and to the canción ranchera.”

Reyes caused a sensation wherever she performed, winning over fans with a natural and authentic stage manner. “The gestures with which she accompanied her performances were not

artificial,”

states Joseph Raúl Hellmer, an ethnomusicologist and specialist in Mexican folklore. “They were part of her identity and they emanated from her feelings. That’s why she was able to easily break though the barrier that often stands between the artist and the audience.”

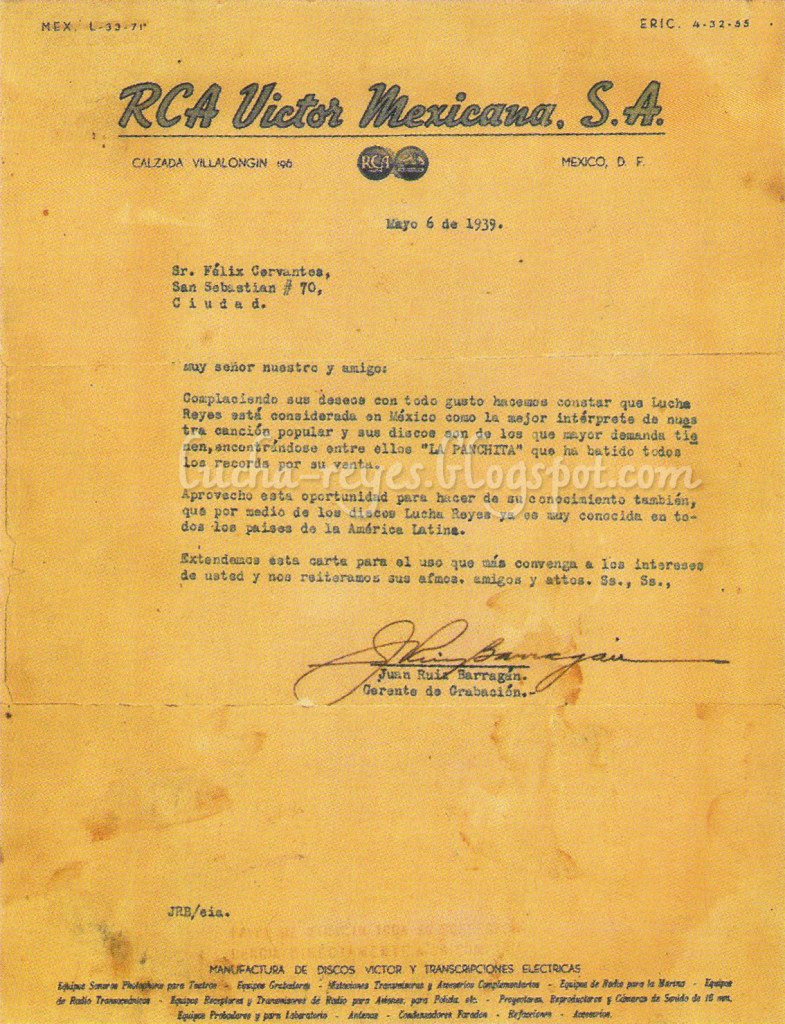

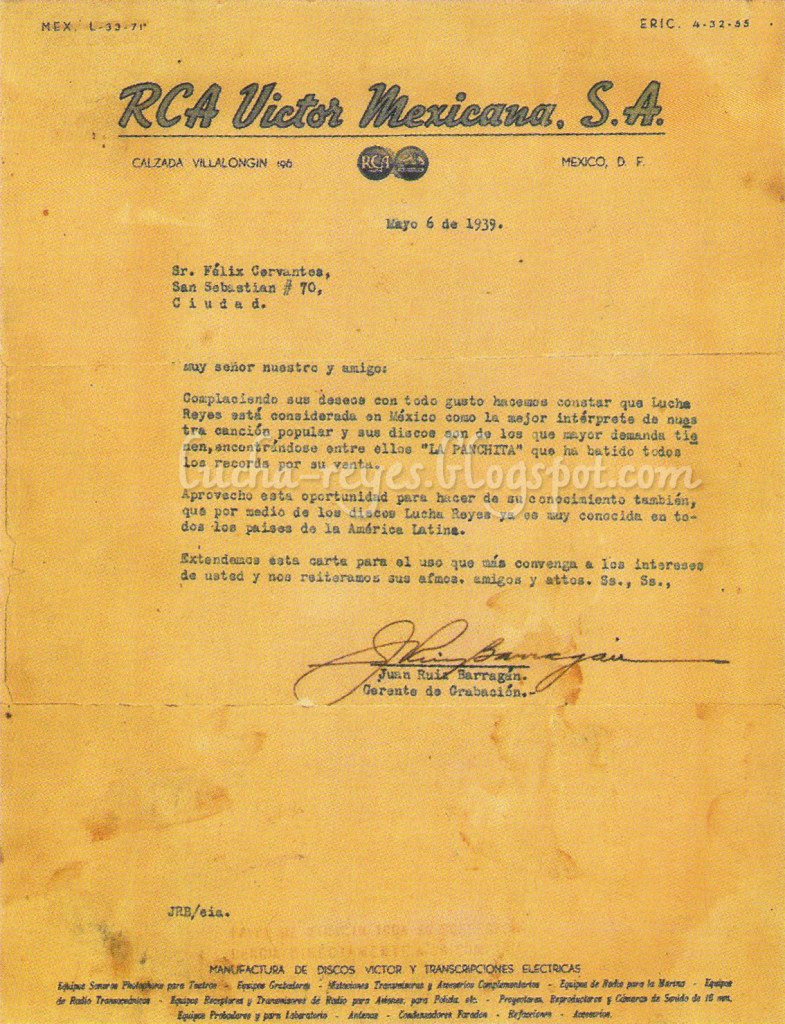

During her career, Reyes debuted and/or popularized many songs by major composers that would become classics of Mexican folk music: “La Feria de las Flores” by Chucho Monge, “Guadalajara” by Pepe Guizar, and

“La Panchita” by Joaquín Pardavé. Her recordings on the Victor label with Mariachi Vargas and Mariachi Tapatío “constitute the archetypal early ranchera recordings by a female singer,” according to mariachi musician and historian Jonathan Clark, who notes that many of her hard-to-find discs are included in The

Frontera Collection.

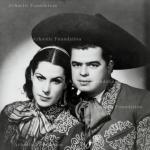

Reyes also performed many hits as a singing star in a series of Mexican movies made between 1935 and 1943, including

“El Herradero” from

Flor Silvestere (1943),

“Con los Dorados de Villa” from the 1939 film of the same name, and of course, in the 1941 classic

¡Ay, Jalisco, No Te Rajes! starringJorge Negrete, in which

she performs the title ranchera song with all the passion and panache that made her so popular.

Although not known as a songwriter, Reyes may have been deprived of songwriting credits. Some fans, for example, believe that Reyes composed her trademark song, “La Tequilera,” one of the few written in a female voice, though it is credited to Alfredo D’Orsay. Curiously, of all the recordings by Reyes in the Frontera Collection, she receives credit as composer on only one,

“Canción Mexicana” (Victor 70-7099-A). However, the song is usually credited to Chicano singer-songwriter Lalo Guerrero, as is the case on this recording by

Lola Beltran, and even on a

separate 33-rpm disc by Reyes herself, released on RCA Victor in the United States.

“If Reyes composed songs without reserving her rights as an author, it would be nothing out of the ordinary,” writes Garcia-Orozco. “Before 1937, women were not allowed to register their copyrights as composers.”

In 1934, Reyes was married a second time, to Felix Martin Cervantes, a talent agent and theater promoter who was “the great love of her life,” according to the Mexico City

newspaper Excelsior. The couple adopted a daughter and named her Maria de Luz Cervantes Flores. But this marriage ended in divorce seven years later, due to her husband’s infidelities, according to

Fauntel’s biography. Greatly disillusioned, Reyes began to drink heavily, a period the biographer calls “the beginning of the end,” the title of one of his final chapters.

On June 25, 1944, Lucha Reyes died in her home in Mexico City from an overdose of barbiturates. She was survived by her third husband, pilot Antonio Vega Medina, as well as her mother and step-daughter. The beloved singer was buried at the Panteón Civil de Dolores, mourned by thousands of fans and top celebrities alike, including Negrete and Mario Moreno a.k.a “Cantinflas,” the comedian and movie star. She was laid to rest while the sounds of her most popular songs were heard, “La Tequilera,” “Guadalajara,” and “La Panchita.”

“She remains in the memory of the Mexican people, who continue to listen to her records and enjoy her way of interpreting the music,” said French filmmaker

Jean-Michel Lacor, who produced the Ripstein film. “Her greatness is comparable to that of mythic characters in the annals of song such as Judy Garland or Edith Piaf, with roles that are melodramatic, fascinating and universal.”

– Agustín Gurza

Add Your Note