the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center,

the Arhoolie Foundation,

and the UCLA Digital Library

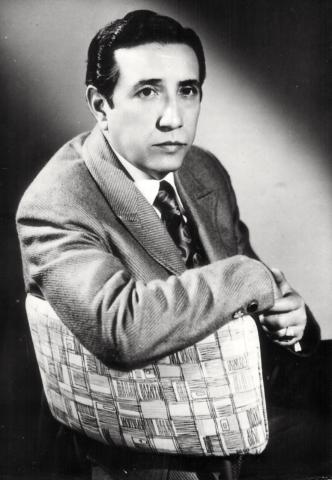

Memo Salamanca was an important composer, arranger, and bandleader who played a prominent role in the popularity of Afro-Cuban dance music that swept Mexico in the 1950s. Salamanca was associated with the leading Cuban artists of the day who had moved to the Mexican capital to ride the mambo craze, including bandleader Perez Prado and venerated Cuban singer Beny Moré.

After the dance fad faded, Salamanca moved back to his native Veracruz, where he explored and promoted other musical genres with strong Afro-Caribbean roots, including the son jarocho and the danzón. In his later years, he was appointed by the state governor as director of the Casa Museo Agustín Lara, named for the famed composer who had been his close friend and collaborator. Salamanca was active as a bandleader and performer right up to the time of his death on August 2, 2008, just 10 days before his 84th birthday.

Although he did not aspire to a career in music as a young man, today he is remembered as an influential musician who helped put a unique stamp on what Mexicans call música afroantillana.

“Memo Salamanca represents, like few others do, one of the most important eras of the Cuban son in Mexico,” writes his biographer, Rafael Figueroa Hernández, on the website Danzon.com. “It was an era in which the son, in many ways, earned a naturalization card in our country, thanks to the work of many Mexican musicians who took it upon themselves to learn and recreate the musical structures created in Cuba. Memo Salamanca, in his role as arranger and bandleader, contributed in many ways to that achievement.”

“Memo Salamanca represents, like few others do, one of the most important eras of the Cuban son in Mexico,” writes his biographer, Rafael Figueroa Hernández, on the website Danzon.com. “It was an era in which the son, in many ways, earned a naturalization card in our country, thanks to the work of many Mexican musicians who took it upon themselves to learn and recreate the musical structures created in Cuba. Memo Salamanca, in his role as arranger and bandleader, contributed in many ways to that achievement.”

Guillermo Salamanca Herrera was born on August 12, 1924 in the city of Tlacotalpan, Veracruz, a historic center for the lively Afro-Mexican style of music and dance known as son jarocho. He was raised in a musical household where both his parents, Guillermo Salamanca Ramos and Carmela Herrera Rodríguez, sang and played various instruments.

Salamanca was a reluctant student of music at first, expressing instead a desire to be an accountant or a stenographer. However, encouraged by his father, he continued his musical studies and eventually made his professional debut at 14, playing piano in a group led by his uncle, Manuel Herrera Rodríguez. When Salamanca was 18, he moved to Veracruz, the state capital, in hopes of finding work as a stenographer, but finding his big break in music instead.

At the time, with World War II raging overseas, job opportunities were limited because maritime commerce, the lifeblood of the port city, had collapsed. Desperate for money, Salamanca accepted an offer to play piano for local radio station XEHV, where he earned one peso per 15-minute show. That exposure landed him a better gig at another station, XEU, with more pay and a higher profile, but also much more pressure. Called upon to accompany well-known vocalists of the day, Salamanca’s piano skills fell short, and the singers complained. The station owner, however, had faith in his pianist’s abilities, so instead of firing Salamanca, he paid for him to get advanced lessons from Sofía de la Hoz, a distinguished piano teacher.

Soon, he had joined the best tropical music band in Veracruz, called Copacabana. In 1945, he moved to Mexico City, where he would begin his long and fruitful association with Cuban artists who were thriving in the capital’s post-war renaissance. He joined a band called Conjunto Habana de Heriberto Pino, with whom he played until the end of the decade.

During that time, Salamanca performed in two films alongside singer-songwriter Agustín Lara, who by then was already a music icon. The films, both released in 1947, were La Diosa Arrodillada (The Kneeling Goddess), starring María Felix, and Pecadora (Sinner), starring Ramón Armengod.

Two years later, at the urging of the great Beny Moré and others, Salamanca joined the orchestra of Arturo Nuñez, marking the start of the peak period of his career in the 1950s. Appropriately, the first song he wrote for the orchestra was “Danzón 1950,” to herald the new year. During the decade to come, Salamanca blossomed as an arranger and composer, writing musical scores for top orchestras, including Luis Alcaraz and Pablo Beltrán Ruiz. He also served as arranger and musical director on recordings by singing stars such as Blanca Rosa Gil and Orlando Guerra “Cascarita” of Cuba, as well as Mexico’s Toña la Negra and Venezuela’s Felipe Pirela, among many others.

With the Cuban dance craze in full swing, Salamanca mastered the various styles coming from the island, becoming one of the first Mexican bandleaders to record a cha cha cha. He also earned the nickname “Prince of the Mambo,” making him runner up to Perez Prado who reigned as mambo king. His compositions rivaled Prado’s in popularity, including “Mambo en Trompeta“ “Mambo a la Núñez“ and “Isabel.” The flamboyant Cuban bandleader even recorded some of Salamanca’s compositions, most notably “Mambo Eté,” with Beny Moré on vocals. Some biographies erroneously give Salamanca credit for writing the big Perez Prado hit “Mambo No. 5,” but the Mexican composer’s mambos were numbered 6 and 7.

Salamanca’s services were in demand by Mexico’s major labels. He helped launch Musart’s tropical series by producing an album by Cuban singer Aurelio Estrada, nicknamed “Yeyo.” And at RCA Victor, famed artistic director Mariano Rivera Conde put Salamanca on the label’s prestigious roster, making him the youngest bandleader, at age 26, to release a record with his own orchestra, featuring vocalist Kiko Mendive.

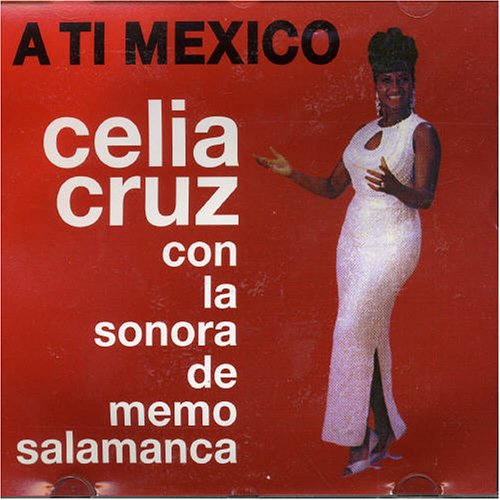

Even U.S.-based Latin labels were recruiting Salamanca as a producer. In 1967, as the new salsa boom took root in New York, the well-known Nuyorican producer-arranger Pancho Cristal tapped Salamanca to work with salsa queen Celia Cruz. That led to an exceptionally fruitful collaboration, yielding five Celia Cruz albums for Tico Records, then the leading Latin music label in Manhattan. The title track of one of those albums, “Serenata Guajira” (Tico LP-1180) is one of Salamanca’s most famous compositions.

The Frontera Collection contains a total of 18 recordings by Salamanca as bandleader, 12 of which he wrote. Half of those tracks are on the RCA Victor label, with two on Musart and four on Peerless.

Salamanca went on to work with his fellow Mexican musicians, composing, recording and touring with Luis Demetrio, Armando Manzanero, and Sergio Esquivel, all singer-songwriters from Yucatan and all stars in their own right.

Eventually, Salamanca’s career hit another lull, and he returned to Veracruz in 1975, and started over. He became the pianist on a popular local television show called El Rincón Bohemio, which for five years served as a cultural showcase for the city’s Caribbean music scene.

Eventually, Salamanca’s career hit another lull, and he returned to Veracruz in 1975, and started over. He became the pianist on a popular local television show called El Rincón Bohemio, which for five years served as a cultural showcase for the city’s Caribbean music scene.

“The final years of his life were ones of mature creativity and constant activity,” according to En Caribe, billed as an online encyclopedia of Caribbean history and culture. “As director of the Casa Museo Agustín Lara, he set about the task of enriching the local musical life with a series of presentations in which he accompanied, with his unique style, practically every singer of the rich port scene.”

Amazingly at this stage, Salamanca was still starting new bands, namely La Charanga del Puerto, Combo de Memo, and La Orquesta de Música Popular. The last made its debut under Salamanca’s direction in April of 2004, the year he turned 80.

Salamanca’s final recording was perhaps his most ambitious. In “Soneros de la Cuenca,” he creates a blend of the two genres that had dominated his career, the son cubano and the son jarocho. He called the fusion “son con son,” demonstrating that the piano was perfectly compatible with the folk music of his home state, usually played with harp and guitars.

Salamanca died on August 2, 2008, and his ashes were spread on the waters of the Río Papaluapan, the mythical river of the butterflies that runs through his hometown of Tlacotalpan. Just eight months earlier, Salamanca was awarded the city’s top artistic award, the Medalla al Mérito Artístico, during an event in which he performed his “son con son.” The newspaper La Jornada, in its obituary for him, described the performance as “an unforgettable experience,” and noted that the honoree, with only months to live, “appeared jovial, surrounded by friends and family.”

Although it had been decades since his heyday as a recording artist with major labels, Salamanca was a composer to the end. He wrote, he said, for his health.

“I still continue to write, even though I’m no longer recording,” he told La Jornada shortly before his death. “If there’s no motivation, you have to look for it. Everything can be a motive for inspiration: a flower, a woman’s look, the words of a friend, the smile of a child.”

-Agustín Gurza

Add Your Note