the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center,

the Arhoolie Foundation,

and the UCLA Digital Library

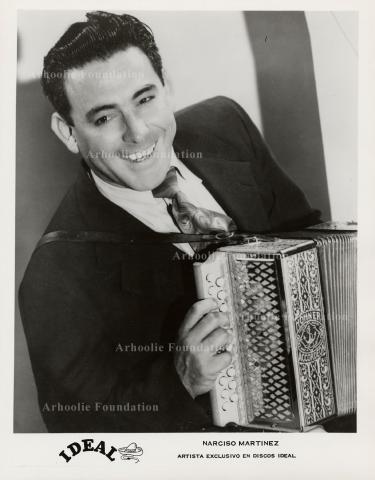

Narciso Martínez, nicknamed “El Huracán del Valle” (the Hurricane of the Valley) for his fast and powerful accordion playing, is acknowledged as the father of conjunto music. He was the genre’s first successful recording artist and the most popular accordion player of his day. No single accordionist was more influential or had a more lasting and widespread impact than Martínez, with hundreds of recording credits over his 60-year career. He was known for a distinctive style that emphasized the melody side of the instrument and left the bass parts to the bajo sexto player. It was a technique that created a snappy, staccato sound that was copied or imitated by virtually every conjunto accordionist who followed him. To this day, his sound is synonymous with Tex-Mex conjunto music.

Martínez was born October 29, 1911, in the border town of Reynosa, Tamaulipas, Mexico. He was brought to the United States that same year and lived most of his life in La Paloma, Texas, near Brownsville, in the region known as the Lower Rio Grande Valley. The son of migrant farmworkers, he received little formal education. In 1928, while still in his teens, he made two decisions that would have life-long impact: He got married and he took up the accordion. He and his wife, Edwina, eventually had four daughters. With the pressures of a growing family, he quickly got good enough on his instrument to perform at dances, picking up techniques from the Czech and German immigrants of the region. In 1930, he bought his first new accordion, a one-row button model made by Hohner, and five years later switched to the more versatile two-row version.

Around this time, in the mid-1930s, he also began his productive association with the remarkable talent of Santiago Almeida, who played the bajo sexto, a 12-string bass guitar. It was that fruitful teaming that established the basic instrumentation of the cojunto and allowed for the duo’s trademark innovation – right-side melody on the accordion, left-side bass notes on the bajo sexto. In 1936, a year after Almeida and Martínez started working together, a local merchant by the name of Enrique Valentin heard them and persuaded them to go to San Antonio to meet Eli Oberstein, the recording director for the Bluebird label, an RCA Victor subsidiary. Their first record – “La Chicharronera” (The Crackling) – was released later that year and became a big hit. Soon, they had the most popular and well-known dance band in South Texas.

Martínez was prolific in the studio, recording up to 20 tracks in one session. His popularity soon extended beyond the Mexican American community. He recorded under the pseudonym “Louisiana Pete” for the Bluebird label’s Cajun series; and for the Polish market, the label marketed his group as the Polski Kwartet. He continued to record for his core audience, doing primarily instrumental polkas, which were his bread and butter, as well as huapangos and Bohemian redovas. His popularity spread nationally and internationally thanks to RCA’s global promotional capabilities. Many of his records were also pressed and distributed in Mexico, a market that generally looked down upon working-class music from north of the border.

After World War II, with the rise of independent, local ethnic labels, Martínez made a move to Ideal Records, based in San Benito, Texas, which was to become a force in the Tex-Mex market. In 1946, the new label’s recording director, Armando Marroquín, hired Martínez for its very first release, now available on the Arhoolie Records compilation Tejano Roots (CD/C 341). As Ideal’s house accordionist, Martínez accompanied some of its most popular artists, notably the duet Carmen y Laura, Las Hermanas Mendoza, María and Juanita, as well as their celebrity sister, Lydia Mendoza, one of the genre’s most popular and respected vocalists. The sound of the duet singers, accompanied by guitars, was long a favorite in the region. Now, with the addition of Martínez’s superb accordion accompaniment, the modern sound of norteño music was born, changing from mainly instrumental dance music to an ensemble featuring singers as the star attractions.

“Narciso Martínez once told me that he felt his lack of singing ability held him back,” wrote Chris Strachwitz in the liner notes to the compilation album Narciso Martínez: Father of the Texas-Mexican Conjunto (Ideal/Arhoolie CD-361). “Perhaps this perceived handicap was actually a blessing since it no doubt contributed to Narciso developing his remarkable talent of mastering a huge repertoire of virtually all regionally popular dance tunes and styles, including polkas, redovas, schottisches, waltzes, mazurkas, boleros, danzones, and huapangos. Narciso learned many of the tunes by having a friend whistle the melody and arrangement which they had recently heard played by a local orchestra or brass band. While his friend – who had a good ear to pick up tunes – whistled, Narciso would pick out the notes on the accordion, thereby transposing the tune to the accordion.”

Almeida, his longtime partner and “left-hand man,” so to speak, stayed with Martínez until 1950 as demand for the touring conjunto was falling off. With increased competition from both sides of the border, older musicians were soon pushed aside. By the late 1950s Martínez had been replaced on the song charts by Conjunto Bernal, Los Alegres de Terán, Los Donneños, Los Relampagos, and other artists who became popular for both their singing and musicianship.

Martínez, like many other conjunto pioneers, never earned much money as a musician. He continued to play on weekends, sometimes at so-called “bailes de negocio” (business dances), where men paid to dance with women. On occasion, he’d be hired by old friends or nostalgic fans to play at special occasions such as anniversaries, quinceañeras, birthday parties, or receptions for baptisms and weddings. But increasingly he felt forced to turn to jobs outside of music to earn a living. In the 1960s and ’70s, he worked as a truck driver, a field hand and a caretaker at the Gladys Porter Zoo in Brownsville.

In 1976, Martínez was featured in Chulas Fronteras, the Strachwitz-produced documentary film by Les Blank about Texas-Mexican music. In the 1980s, Martínez continued to receive accolades and recognition for his music and cultural contributions, from both within and outside his own community. He was inducted into the Conjunto Music Hall of Fame in 1982 and was honored the following year with a National Heritage Award from the National Endowment for the Arts for his contributions to the nation's cultural heritage. In 1991, the Narciso Martínez Cultural Arts Center was named in his honor in San Benito, Texas, near his life-long home of La Paloma. In January of the following year, his last album was released, 16 Éxitos de Narciso Martínez (16 Hits of Narciso Martínez), on the R y R label of Monterrey, Nuevo León.

In May of 1992, Martínez was scheduled to appear at the annual Tejano Conjunto Festival in San Antonio. Instead, he was admitted to the hospital and diagnosed with leukemia. Narciso Martínez, El Huracán del Valle, died in San Benito on June 5, 1992.

Posthumous honors continued after his death. Martínez was an inaugural inductee into the Tejano R.O.O.T.S. Hall of Fame in 2000. Two years later he was inducted into the Texas Conjunto Music Hall of Fame. He is also an inductee in the Houston Institute for Culture Texas Music Hall of Fame. And each year since 1992, a hurricane blows through San Benito once again at the annual Narciso Martínez Conjunto Festival, which showcases old and new forms of the genre and celebrates its pioneer.

– Agustín Gurza

Add Your Note