the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center,

the Arhoolie Foundation,

and the UCLA Digital Library

Americans remember Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna as the Mexican general who defeated Texas insurgents at the Alamo. Mexicans remember him as the self-aggrandizing leader who lost half the nation’s territory in the war with the United States. Few people, however, remember him as a patron of the arts. It’s a little-known fact that Santa Anna was the assiduous sponsor of a literary competition that produced the modern Mexican National Anthem, with lyrics by a reluctant poet and music by a classically trained Catalan composer.

Americans remember Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna as the Mexican general who defeated Texas insurgents at the Alamo. Mexicans remember him as the self-aggrandizing leader who lost half the nation’s territory in the war with the United States. Few people, however, remember him as a patron of the arts. It’s a little-known fact that Santa Anna was the assiduous sponsor of a literary competition that produced the modern Mexican National Anthem, with lyrics by a reluctant poet and music by a classically trained Catalan composer.

The anthem is considered one of the few uplifting legacies of the general’s long and ignominious reign. There may be no statues or memorials in Mexico to the disgraced president, but Santa Anna left an indelible emblem on the country with a rousing anthem considered outstanding among the hymns of modern nations.

“It is regarded as one of the most beautiful national anthems, along with the French ‘La Marseillaise’ and the former Soviet Union’s ‘The Internationale,’ ” wrote David Crow, contributor to the World Association of International Studies, an online journal founded at Stanford University.

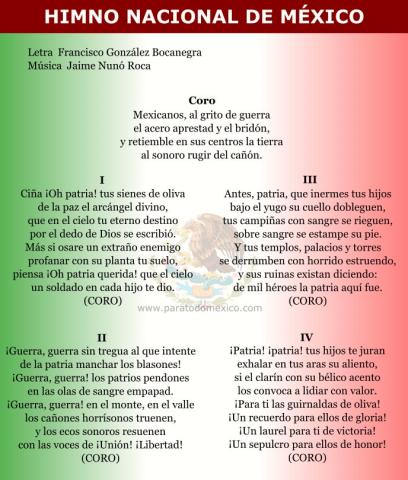

After the Mexican War of Independence in 1810, it took three decades and several attempts to produce an anthem that would suit warring factions in the nascent nation. Hymns were adopted then discarded, reflecting the era’s frequent political ups and downs. The final version was created in 1854, but it would take almost another century before it was adopted, in an edited version, as the official national song.

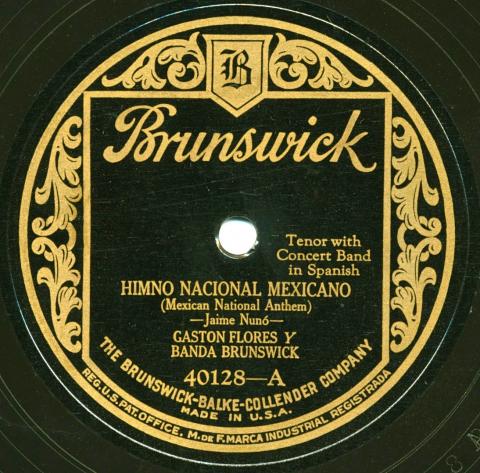

The Frontera Collection has a dozen recordings of the anthem, all but one on 78-rpm discs. Most, however, are instrumentals, performed by a variety of police, military, and bullfighter bands.

The two composers who wrote the song’s words and music, Francisco González and Jaime Nunó, collaborated only for that one patriotic purpose. Unlike Santa Anna, who lives in infamy, these artists had been almost forgotten by history, though their memory has gradually been restored. More people are now familiar with their personal stories, which feature fascinating tales of hardship, ambition, romance, adventure, and luck.

An Anthem Is Born

González and Nunó lived through an era of almost constant turmoil and upheaval in Mexico. During their youth in the first half of the 19th century, the country faced a series of existential crises, first the instability of independence then the war with the United States (1846-1848), which cost half its territory and much of its national pride.

The moment was ripe for efforts to restore the nation’s battered sense of identity, and build a new sense of national unity. What the young country needed was a patriotic national anthem people could rally around. In the four years between 1849 and 1853, four calls were made to select a qualifying song to lift Mexico’s spirit.

Just one problem: Most of the submissions were from foreigners. The winners of the first competition, for example, were an Austrian musician and a U.S. poet, which was particularly galling to the citizenry. Subsequent short-lived anthems were penned by various Italian, French, Cuban, and Czech composers, but they all fell flat.

After those failed attempts, who should re-enter the national stage but General Santa Anna, who was in and out of office 11 times over more than two decades (1833 – 1855). In April of 1853, he returned from exile in Venezuela just in time to call for another anthem competition. It was launched in November of that year, eliciting patriotic poems by more than two dozen aspiring scribes.

These competitions were not dry bureaucratic affairs. They were handled by a lively activist group called the Academia de Letrán, a roundtable of poets, writers, and statesmen led by Andres Quintana Roo, a lawyer and publisher who spearheaded the independence movement. Housed in the historic center of the Mexican capital – on the old Avenida San Juan de Letrán, now Eje Central Lázaro Cárdenas – these men of letters would gather to read and critique one another’s work, suggesting editorial changes by democratic vote. The meetings could get boisterous.

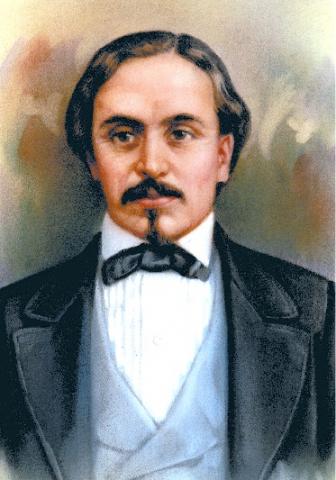

The winner of the latest contest was a relatively unknown poet from San Luis Potosí, Francisco González Bocanegra, then just 29 years old. At first, his florid and bellicose verses were set to music by composer and double-bass player Giovanni Bottesini, but the Italian’s score was considered inadequate; that is, “not aesthetically pleasing.”

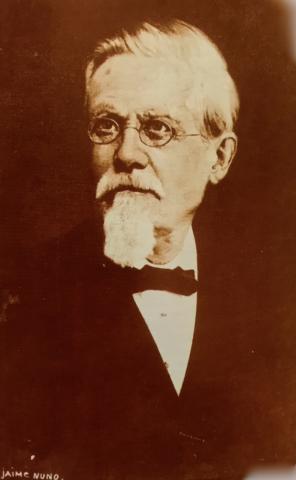

So a new competition was launched to select a different composer, drawing 15 new entries. The winner was a Catalan musician named Jaime Nunó Roca, also 29, recently arrived in Mexico via Cuba as Santa Anna’s hand-picked director of the nation’s military bands.

Gonzalez and Nunó could hardly be considered a writing team, since they didn’t work together. Yet, their efforts yielded a triumphant anthem that would survive the tumultuous fluctuations of Mexican politics. Over ensuing decades, it was banned then reinstated depending on the ruling ideology. It was first performed in 1854, at the historic theater named for its political sponsor, during his final reign as president. Santa Anna attended a performance just in time, before being booted into exile for good the following year.

The composers also went their separate ways—one remaining in Mexico where he died young, the other moving to New York where he lived a long life. They were reunited again only in death, when their remains were brought together in a Mexico City cemetery.

During their lives, Gonzalez and Nunó experienced their share of hardship, migration, and exile, sometimes self-imposed. Like Mexico itself, their lives were in a state of constant flux.

The Reluctant Lyricist

González Bocanegra was the son of a Spanish military officer whose family was forced to flee Mexico after the 1810 War of Independence against Spain. From San Luis Potosí they moved to the Spanish port city of Cádiz in 1829, following orders expelling all Spanish males from the country. They returned in 1836 when Spain finally recognized Mexico’s new sovereign status. Ten years later, the young bard moved to Mexico City, where he mingled with other poets, writers, and journalists of the day, joining the Academia Letrán, considered “the heart and soul of the intellectual stirrings” of a new generation.

González Bocanegra was the son of a Spanish military officer whose family was forced to flee Mexico after the 1810 War of Independence against Spain. From San Luis Potosí they moved to the Spanish port city of Cádiz in 1829, following orders expelling all Spanish males from the country. They returned in 1836 when Spain finally recognized Mexico’s new sovereign status. Ten years later, the young bard moved to Mexico City, where he mingled with other poets, writers, and journalists of the day, joining the Academia Letrán, considered “the heart and soul of the intellectual stirrings” of a new generation.

Gonzalez made a living as a merchant, as had his parents who helped support his literary endeavors. But he soon switched to public service, working as a roadway administrator, a theater censor, and editor of the federal government’s official organ, the Diario Oficial del Supremo Gobierno. In Mexico City, he also started publishing his first poems, but with little notice.

The story of how Gonzalez rose to fame as the anthem’s author proves the old maxim “Behind every great man there’s a great woman.” In this case, that would be his fiancé, Guadalupe González del Pino y Villalpando.

As legend has it, the poet was unwilling to participate in the competition at first, arguing that he was skilled in romantic verse, not patriotic songs. He demurred, despite the persistent urging from Pili, as his fiancé was nicknamed, and her friends. So the bride-to-be escalated the pressure, locking her lover in a room in her parent’s home, equipped with quill and writing paper and furnished with historical books and paintings for inspiration. She threatened not to set him free until he had penned a worthy entry.

Four hours later, the imprisoned poet slipped the pages of his anthem under the door, delighting his betrothed who instantly liberated him from his literary confines. The oft-told story sounds more like Disney than history. But the fact is the couple soon married and attended the inaugural anthem performance as man and wife (who also happened to be his cousin).

González’ fervent anthem – also known as “¡Mexicanos, al Grito de Guerra!” – won by unanimous vote, as officially announced on February 3, 1854.

The only thing missing was the music.

The Queen’s Conductor

Composer Jaime Nunó Roca was born in 1824, the youngest of eight children in a poor family from Sant Joan de les Abadesses, a small rural town north of Barcelona. When he was five, his father died of a poisonous bite from a snake, or scorpion. Three years later, he and his mother moved to Barcelona, fleeing a regional cholera outbreak. But it was too late; his mother died of the disease shortly thereafter, and the boy was left orphaned at age 10.

These early hardships did not prevent him from blossoming as a musician. Jaume, as his name appears in Catalan, started his musical studies in Barcelona under the tutelage of an uncle, who took him in. He became a soloist in the local cathedral choir and by the time he was 17, he had earned a scholarship to study classical music in Rome. He started composing music for church masses and small orchestras, as well as directing military bands. That led to his appointment in 1851 as director of La Banda del Regimiento de Infantería de la Reina, with which he soon sailed to Cuba.

It was in Havana that he crossed paths, literally, with Gen. Santa Anna, who was on his way back to Mexico from exile in South America, to serve what would be his final term. The two struck up an unlikely friendship, and the irrepressible general quickly invited the composer to join him in Mexico as director of his country’s military bands.

It was in Havana that he crossed paths, literally, with Gen. Santa Anna, who was on his way back to Mexico from exile in South America, to serve what would be his final term. The two struck up an unlikely friendship, and the irrepressible general quickly invited the composer to join him in Mexico as director of his country’s military bands.

Nunó accepted Santa Anna’s generous offer, earning a higher salary than top officers, which did not sit well with the brass. The musician arrived in 1853, just in time to participate in the anthem competition, sponsored by his new commander and patron.

Nunó entered the contest anonymously, knowing his name could cause controversy and suspicions of favoritism. To make the judging more objective, he asked a friend, Narciso Bassols, to transcribe his score, so as to disguise his penmanship. Since his winning entry, entitled “Dios y Libertad” (God and Liberty), had only his initials, officials published an announcement asking “J.N.” to identify himself. In August of 1984, Nunó was publicly unveiled as the winning composer, leaving his much-loved music to drown out any lingering disquiet.

A critic at the time described Nunó’s work as the perfect combination of “Italian floridity, German vigor, and American grandiosity.”

The Mexican National Anthem was first performed on Friday, September 15, 1854, at the Gran Teatro de Santa Anna, an architectural jewel of its time. Notably, the orchestra was under the direction of the maestro Bottesini, whose own score had been rejected and who was apparently a good sport. Missing from the audience was the president who had commissioned the work. So it was performed again the following day, Mexican Independence Day, with His Most Serene Highness in attendance. This time, Nunó himself was the conductor.

The following year, after Santa Anna sold off more Mexican land in the Gadsden Purchase, he was again sent into exile, for the final time. His name was expunged from the theater where the anthem had been gloriously performed, and adoring references to him were unceremoniously stripped from the verses. It would take 90 years for the country to settle on a shortened version of the anthem that deleted reminders of embarrassing chapters in its history.

Just as the anthem fell out of favor in ensuing decades, Nunó himself felt his fortunes fall after Santa Anna left the scene.

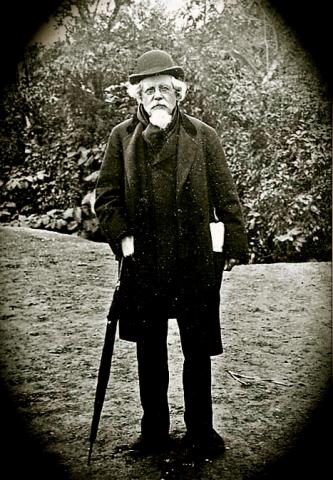

Nunó returned to Cuba then sailed on to the United States in 1856. For the next decade, he worked as an opera and orchestra director, touring the United States and based for a period in Havana. In 1869, he finally settled in Buffalo, New York, where he gave singing classes.

Nunó returned to Cuba then sailed on to the United States in 1856. For the next decade, he worked as an opera and orchestra director, touring the United States and based for a period in Havana. In 1869, he finally settled in Buffalo, New York, where he gave singing classes.

Four years later, he married one of his best students, Kate Cecilia Remington, who was 30 years his junior and the daughter of historian Cyrus Remington. The couple had three children, a son and two daughters.

Back in Mexico, people had lost track of the composer and presumed him dead. By chance, Nunó was re-discovered in 1901 by a reporter attending the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, where President McKinley was assassinated. That led to a triumphant return to Mexico, where he was received like a celebrity and lavished with medals and honors.

In 1904, on the 50th anniversary of the national anthem, Nunó was invited back to Mexico, this time at the invitation of President Porfirio Diaz, the military dictator who had re-established the militaristic hymn as part of official ceremonies.

Following his death in New York in 1908, Nunó once again fell into obscurity. His memory was revived recently, however, by two of his Catalan countrymen who researched and wrote his definitive biography, Nunó: Un Santjoanino en América.

The authors, Cristian Canton Ferrer and Raquel Tovar Abad, tracked down the composer’s great-grandson, Edwin B. Cragin, who had kept a treasure trove of the composer’s history in his attic, material hidden for a century. It included letters from two presidents, Santa Anna and Porfirio Diaz, as well as unpublished scores and even the baton he used in the anthem’s inaugural performance.

Though the anthem overshadowed other works, Nunó composed more than 600 pieces for orchestra, piano, and chorales. Unfortunately, less than two dozen survive, largely in museums and private collections, according to his biographers.

The life of Nunó’s co-writer, Gonzalez Bocanegra, came to a much less fortunate denouement. He continued to work in public service jobs, and also continued to write poetry, theater reviews, and even a historical play, Vasco Núñez de Balboa, which debuted at the Teatro Iturbide on September 14, 1856. Six years earlier, he had co-founded El Liceo Hidalgo, a literary club to succeed the by-then defunct Letrán academy.

In 1861, after conservatives were defeated and the liberal Benito Juarez became president, Gonzalez found himself caught in the political crossfires. Persecuted by enemies, he sought refuge at a friend’s house. In April of that year, he died of typhus, still in hiding, separated from his wife, his ardent supporter, and their four daughters. He was just 37.

From Obscurity to the Pantheon

The anthem was not officially adopted by the government until 1943, by order of President Manuel Ávila Camacho. The law also codified the allowable verses, keeping just four of the original ten stanzas, plus the chorus. No mention was left of Santa Anna nor Agustín de Iturbide, the Mexican emperor who was exiled and then executed. In an attempt to bring ceremonial stability to the politically battered hymn, the law imposed a jail sentence of from one to six months for altering its structure or violating the rules governing its performance, though the term was later reduced to 36 hours. (An abridged version was approved for sporting events, like the Olympic Games or World Cup.)

More recently, the government allowed the anthem to be translated into indigenous languages, including Náhuatl, the ancient language of the Aztecs.

More recently, the government allowed the anthem to be translated into indigenous languages, including Náhuatl, the ancient language of the Aztecs.

González Bocanegra never lived to see his anthem’s respectability restored. In 1931, seven decades after his death, the poet’s remains were moved by presidential decree to the Rotonda de los Hombres Ilustres (Rotunda of Illustrious Men), in the capital’s Panteón Civil de Dolores, where he joined Mexican luminaries such as composer Carlos Chavez and muralists David Alfaro Siqueiros and Diego Rivera.

In 1942, again by order of the Mexican government, the remains of his co-author, Nunó, were exhumed from the Forest Lawn Cemetery in Buffalo, where he had been buried, and returned to Mexico. (Nunó's original gravestone remains in place next to his wife’s in the Remington family lot, with an explanation of the move.)

The two composers finally found their common resting place, interred together in the same area of Dolores Cemetery reserved for Mexico’s illustrious figures. Nunó is said to be the only non-Mexican to have received the burial honor.

“The fact that (The Mexican National Anthem) was written by a Mexican poet and composed by a Spanish musician makes it the more nostalgic,” wrote Crow on the academic message board, “for it symbolizes the cultural blend that created this country.”

– Agustín Gurza

0 Comments

Stay informed on our latest news!

Add your comment