the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center,

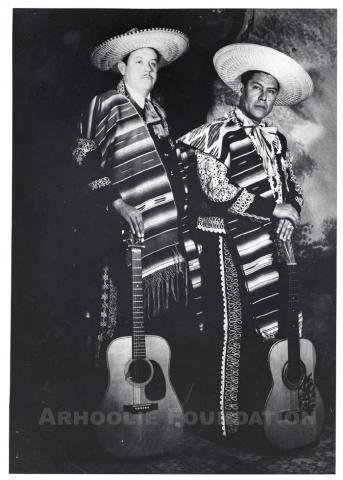

the Arhoolie Foundation,

and the UCLA Digital Library

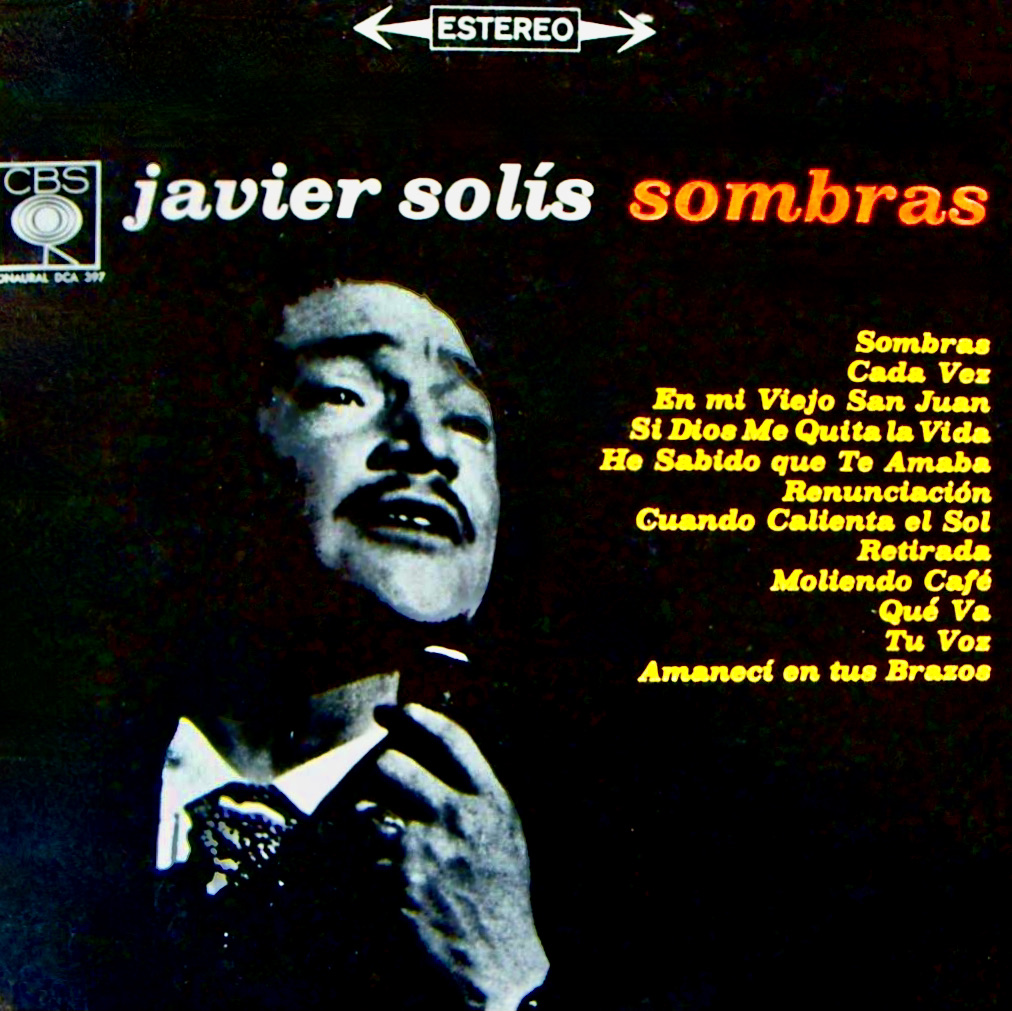

In the first installment of my three-part series on the bolero, I offered an overview of the romantic genre and highlighted songs I had learned from my parents as a ch

In the first installment of my three-part series on the bolero, I offered an overview of the romantic genre and highlighted songs I had learned from my parents as a ch

Many countries have iconic images and unofficial anthems that capture the essence of the national spirit. In the United States, there’s the high-stepping tune “Yankee Doodle Dandy.” Sometimes, just a few words are enough to evoke a familiar cause and its historic significance. Rosie the Riveter. The suffragettes. The colonial minutemen. We can easily picture them in our mind’s eye, with any attendant nostalgia or national pride.

Many countries have iconic images and unofficial anthems that capture the essence of the national spirit. In the United States, there’s the high-stepping tune “Yankee Doodle Dandy.” Sometimes, just a few words are enough to evoke a familiar cause and its historic significance. Rosie the Riveter. The suffragettes. The colonial minutemen. We can easily picture them in our mind’s eye, with any attendant nostalgia or national pride.

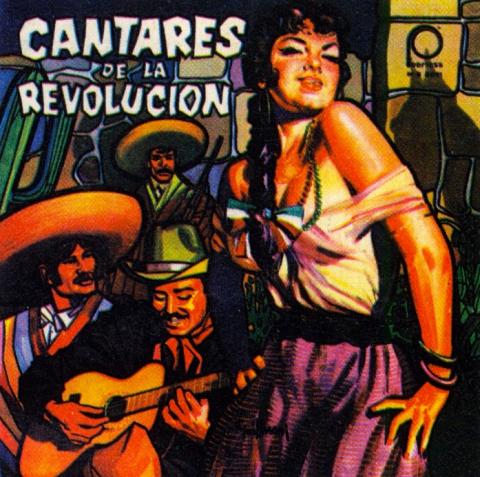

In Mexico, one iconic female figure embodies that cultural and historic significance. La Adelita, a mythical composite persona, represents the thousands of unknown women who joined the Revolution of 1910, playing various key roles in the popular uprising that overthrew the Euro-centric dictatorship of Porfirio Diaz.

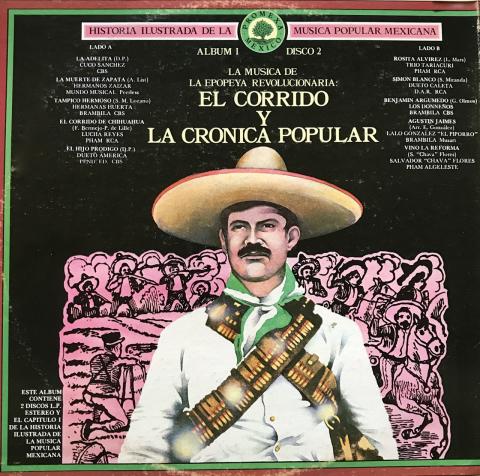

The Mexican Revolution of 1910, with its epic heroes facing life-and death struggles, ushered in a golden age of the corrido. In the introduction to his 1954 anthology, “El Corrido Mexicano,” corrido historian Vicente T. Mendoza asserts that the narrative ballad achieved its “definitive character” during Mexico’s decade of Civil War, acquiring “its true independence, fullness and epic character in the heat of combat.”

The Mexican Revolution of 1910, with its epic heroes facing life-and death struggles, ushered in a golden age of the corrido. In the introduction to his 1954 anthology, “El Corrido Mexicano,” corrido historian Vicente T. Mendoza asserts that the narrative ballad achieved its “definitive character” during Mexico’s decade of Civil War, acquiring “its true independence, fullness and epic character in the heat of combat.”

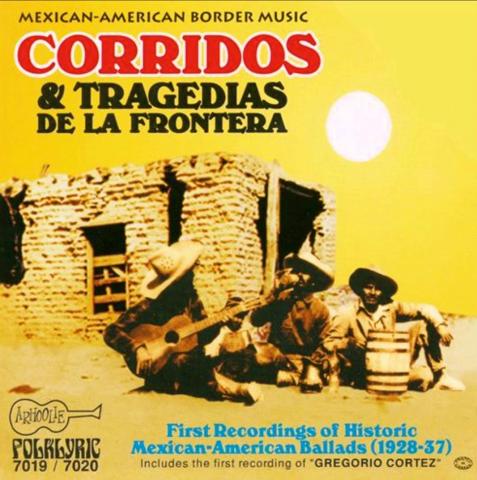

During the first half of the 20th century, the corrido went from an oral tradition to a recorded, commercial art form. But in making that transition, corrido artists had to adapt their long narrative ballads to the recording technology of the day, primarily the old 78-rpm shellac discs.

During the first half of the 20th century, the corrido went from an oral tradition to a recorded, commercial art form. But in making that transition, corrido artists had to adapt their long narrative ballads to the recording technology of the day, primarily the old 78-rpm shellac discs.

As we saw in Part 1, the corrido developed as an oral tradition in the last half of the 19th century. The narrative ballad was cultivated along the border, fueled by the cultural conflict left in the wake of the U.S. War with Mexico. These early border ballads, which reached their peak between 1860 and 1910, depicted the exploits of protagonists caught up in these culture wars, often through no desire of their own.

As we saw in Part 1, the corrido developed as an oral tradition in the last half of the 19th century. The narrative ballad was cultivated along the border, fueled by the cultural conflict left in the wake of the U.S. War with Mexico. These early border ballads, which reached their peak between 1860 and 1910, depicted the exploits of protagonists caught up in these culture wars, often through no desire of their own.

The corrido is often described as a narrative ballad, which is an accurate though insufficient definition. Narrative ballads exist in many countries, including the United States. But the form that developed in Mexico in the late 1800s is deeply rooted in that country’s specific cultural history, and especially the inequitable relationship with its conquering neighbor to the North.

The corrido is often described as a narrative ballad, which is an accurate though insufficient definition. Narrative ballads exist in many countries, including the United States. But the form that developed in Mexico in the late 1800s is deeply rooted in that country’s specific cultural history, and especially the inequitable relationship with its conquering neighbor to the North.

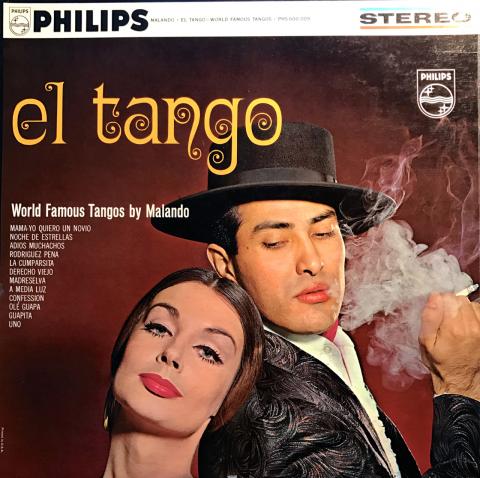

The Argentine tango is one of a handful of song-and-dance styles – along with Spanish flamenco and the Cuban mambo – that emerged from cultural fusions in the Spanish-speaking world and gained global popularity in the 20th century. The tango craze that swept Europe and the U.S. during the first half of the last century may have faded. But the tango as an art form still thrives, in both traditional and contemporary forms.

The Argentine tango is one of a handful of song-and-dance styles – along with Spanish flamenco and the Cuban mambo – that emerged from cultural fusions in the Spanish-speaking world and gained global popularity in the 20th century. The tango craze that swept Europe and the U.S. during the first half of the last century may have faded. But the tango as an art form still thrives, in both traditional and contemporary forms.

It is one of the most recognizable beats in the history of popular dance music: One, two, cha-cha-cha.

It is one of the most recognizable beats in the history of popular dance music: One, two, cha-cha-cha.

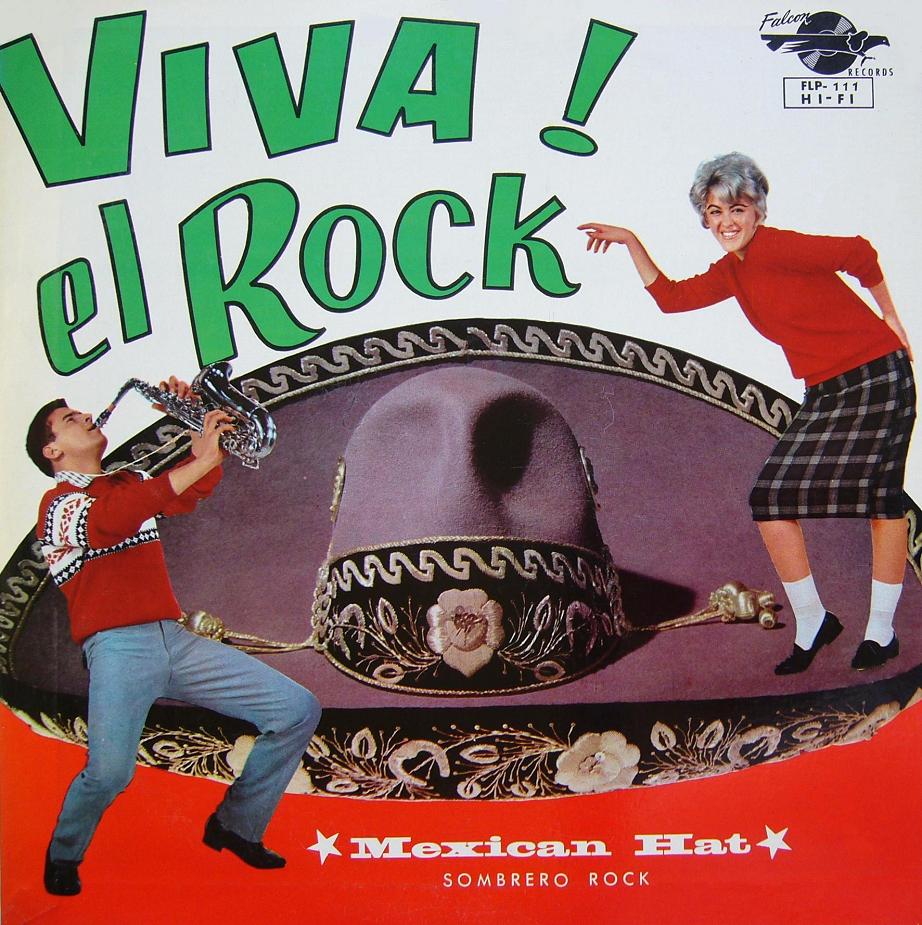

For a time in the 1950s, this Afro-Cuban rhythm also became a dance craze that swept the western world, from Paris to Caracas, from New York to Mexico City. The cha-cha-cha became one of the staples of ballroom dancing, along with the mambo and the rumba. Simultaneously, the light and cheerful beat of this new dance rhythm also seeped into the DNA of early rock ‘n’ roll.

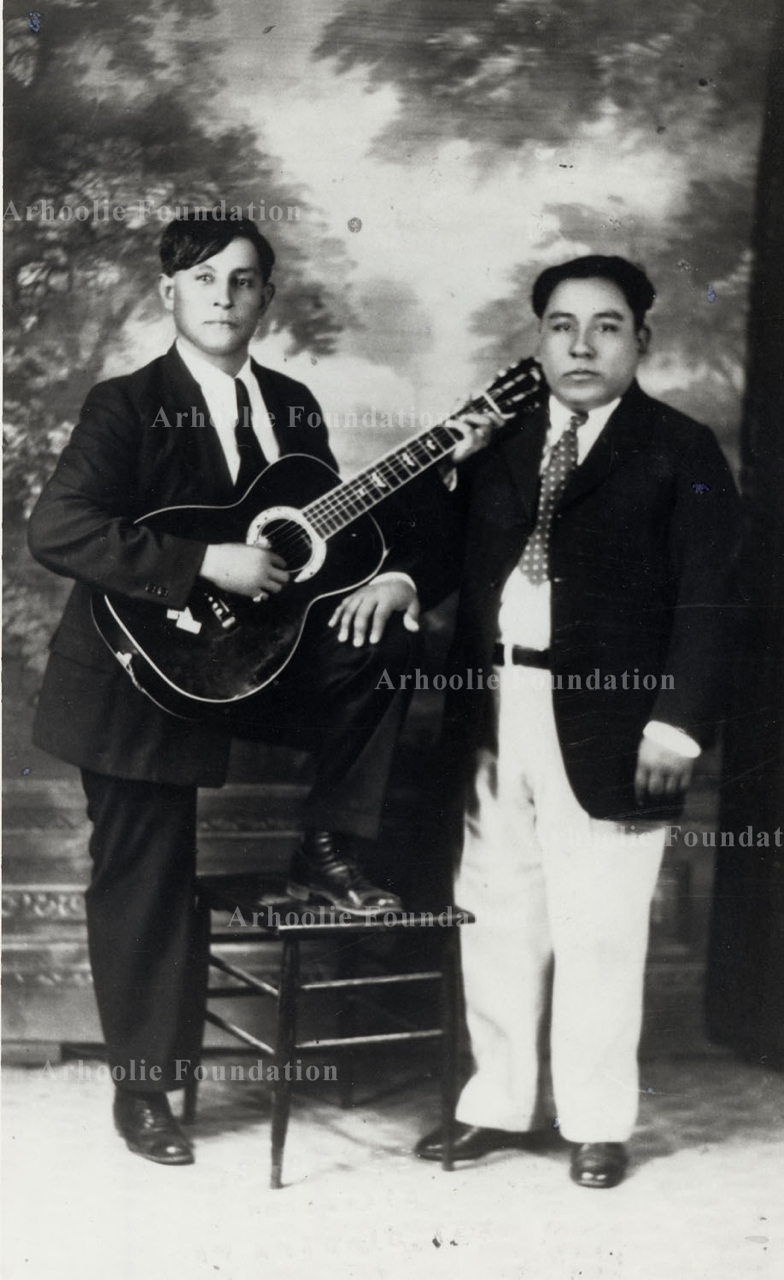

One of the most important contributions of the Frontera Collection is the documentation of Mexican-American music, a cultural legacy that may have otherwise been lost or overlooked. Both as a writer and a record collector, I am often dismayed at how little information is available on artists and their recordings, not just Mexican Americans but Latino musicians in general.

One of the most important contributions of the Frontera Collection is the documentation of Mexican-American music, a cultural legacy that may have otherwise been lost or overlooked. Both as a writer and a record collector, I am often dismayed at how little information is available on artists and their recordings, not just Mexican Americans but Latino musicians in general.

Mexican Americans have produced memorable musical fusions over the past half-century. Best known perhaps are two California strains: the salsa-rock of Carlos Santana from San Francisco and the blues-meets-jarocho sound of Los Lobos in Los Angeles. A lesser known but equally enduring style comes from the Lone Star State: Tejano rock. It’s a blend of melodic Tex-Mex accordion, edgy electric guitar, and a touch of raucous rockabilly.

Mexican Americans have produced memorable musical fusions over the past half-century. Best known perhaps are two California strains: the salsa-rock of Carlos Santana from San Francisco and the blues-meets-jarocho sound of Los Lobos in Los Angeles. A lesser known but equally enduring style comes from the Lone Star State: Tejano rock. It’s a blend of melodic Tex-Mex accordion, edgy electric guitar, and a touch of raucous rockabilly.

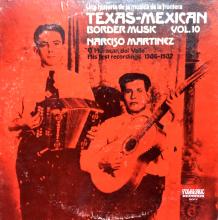

Conjunto music, the accordion style so popular with Mexican Americans throughout the Southwest, comprises a cornerstone of the Frontera Collection. Yet conjunto as such does not appear on the list of Top 20 genres compiled for my book about the Frontera archive and published in 2012 by the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Press. That fact points to a confusion about the term that sometimes stumps even fans familiar with the genre.

Conjunto music, the accordion style so popular with Mexican Americans throughout the Southwest, comprises a cornerstone of the Frontera Collection. Yet conjunto as such does not appear on the list of Top 20 genres compiled for my book about the Frontera archive and published in 2012 by the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Press. That fact points to a confusion about the term that sometimes stumps even fans familiar with the genre.

Stay informed on our latest news!