the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center,

the Arhoolie Foundation,

and the UCLA Digital Library

Part 2: Border Bandits or Folk Heroes

As we saw in Part 1, the corrido developed as an oral tradition in the last half of the 19th century. The narrative ballad was cultivated along the border, fueled by the cultural conflict left in the wake of the U.S. War with Mexico. These early border ballads, which reached their peak between 1860 and 1910, depicted the exploits of protagonists caught up in these culture wars, often through no desire of their own.

As we saw in Part 1, the corrido developed as an oral tradition in the last half of the 19th century. The narrative ballad was cultivated along the border, fueled by the cultural conflict left in the wake of the U.S. War with Mexico. These early border ballads, which reached their peak between 1860 and 1910, depicted the exploits of protagonists caught up in these culture wars, often through no desire of their own.

Cultural differences also defined the ways the protagonists were depicted, as heroes or villains, depending on the point of view. To Anglos, they were bandits and outlaws who deserved to be tracked down and imprisoned or killed. To corrido fans, however, they were folk heroes locked in a heroic struggle against the prejudice and brutality of Anglo society. For many Mexicans, the corrido became the expression of cultural resistance against the advancing dominant Anglo culture driven by Manifest Destiny.

Up until the time of the Mexican Revolution, the early corridos were populated by these modern-day Robin Hoods. One such corrido spread the news of daring actions by Juan Nepomuceno Cortina, a Mexican politician and military leader who led guerilla raids along the Texas border to avenge the mistreatment of his countrymen. Corrido scholar Américo Paredes called Cortina “the first corrido hero” to emerge from the Lower Rio Grande Valley.

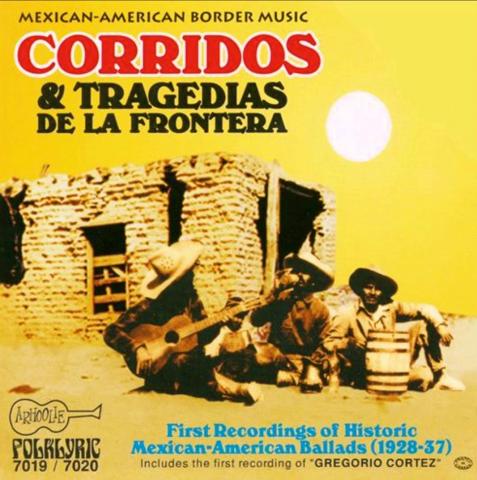

The Frontera Collection has multiple recordings of corridos inspired by these border rebels who became legends throughout the Southwest. Among the most notorious of these heroic outlaws is Gregorio Cortez, a Mexican-American tenant corn farmer who shot and killed a Texas Ranger in what he considered self-defense.

The incident took place in 1901 in Gonzales, Texas, when Texas Rangers, who were investigating a horse theft, came to question Cortez and his brother, Romaldo, at the ranch where they worked. The investigation took a violent turn as a result of a linguistic misunderstanding between Cortez and a translator for the Rangers, referred to as “rinches” in the phonetic vernacular of border language. In the confusion, a Ranger shot the brother, and Cortez returned fire, killing the Ranger before escaping. This deadly failure to communicate underscored the tension between the increasingly marginalized Mexican-American population and the overtly racist Anglo power structure along the border's cultural hot zone.

The incident took place in 1901 in Gonzales, Texas, when Texas Rangers, who were investigating a horse theft, came to question Cortez and his brother, Romaldo, at the ranch where they worked. The investigation took a violent turn as a result of a linguistic misunderstanding between Cortez and a translator for the Rangers, referred to as “rinches” in the phonetic vernacular of border language. In the confusion, a Ranger shot the brother, and Cortez returned fire, killing the Ranger before escaping. This deadly failure to communicate underscored the tension between the increasingly marginalized Mexican-American population and the overtly racist Anglo power structure along the border's cultural hot zone.

Though hated by Anglos in South Texas, corridos depict Cortez as an innocent farmer goaded into fighting “outsiders” and defending the honor of his countrymen. He is lionized for his ability to repeatedly elude capture, covering more than 500 miles as a fugitive, on foot and on horseback. At one point, he was pursued by a posse of 300 men, one of the largest manhunts in U.S. history.

Yo no soy Americano pero comprendo el inglés.

Yo lo aprendí con mi hermano al derecho y al revés.

A cualquier Americano hago temblar a mis pies.

Por cantinas me metí castigando americanos.

"Tú serás el capitán que mataste a mi hermano.

Lo agarraste indefenso, orgulloso americano."

I am not an American but I understand English.

I learned it with my brother, backwards and forwards.

And any American I make tremble at my feet.

Through cantinas I went punishing Americans.

"You must be the captain who killed my brother.

You took him defenseless, you boastful American."

The story of Gregorio Cortez, documented on the front pages of newspapers in both languages, is recounted in detail by Paredes in his 1958 book, With His Pistol in His Hand: A Border Ballad and its Hero “Gregorio Cortez.” It was also turned into a television movie in 1982, The Ballad of Gregorio Cortez, starring Edward James Olmos.

The corrido ends with the hero’s capture, but there’s much more to the story after that. Cortez was almost lynched while in jail, and his case provoked mob attacks on the Mexican population of the Rio Grande Valley. The racial tensions were inflamed by a sensationalist Anglo press that called Cortez an “arch fiend” and lamented the fact that he had been spared from being lynched. Decades later, the animosity was still so intense that a Texas Ranger threatened to shoot author Paredes after the publication of his book on the outlaw.

The corrido ends with the hero’s capture, but there’s much more to the story after that. Cortez was almost lynched while in jail, and his case provoked mob attacks on the Mexican population of the Rio Grande Valley. The racial tensions were inflamed by a sensationalist Anglo press that called Cortez an “arch fiend” and lamented the fact that he had been spared from being lynched. Decades later, the animosity was still so intense that a Texas Ranger threatened to shoot author Paredes after the publication of his book on the outlaw.

Cortez was convicted, exonerated on appeal, tried again and eventually sentenced to life. Amazingly, he was pardoned by the Texas governor after an appeal for clemency from a most unlikely source, Abraham Lincoln’s daughter. He was released and then remarried for the fourth and final time shortly before dying in 1916. The official cause of death was pneumonia, though his family always believed Cortez was poisoned.

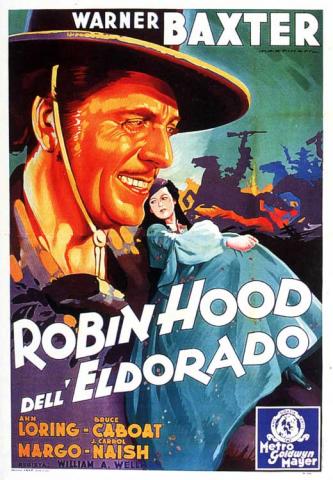

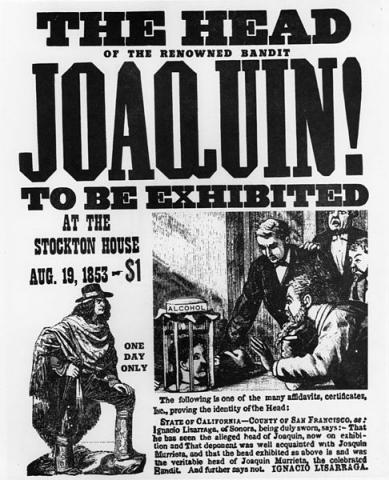

Another famous corrido from this era tells the story of Joaquín Murrieta, a 19th century Mexican immigrant whose severed head was put on public display in mining towns throughout the state. The daring outlaw, often pictured with long dark hair blowing in the wind, was also the subject of alarmist newspaper articles, dime-store novels and a book that became a Hollywood movie, “The Robin Hood of El Dorado,” released in 1936.

Historically, not much is known about Murrieta, who came from Sonora as a young man to join the California Gold Rush. The corrido chronicles his transformation from an immigrant seeking his fortune to an outlaw seeking revenge on “vain Anglos” for killing his wife and his defenseless brother in cold blood. For author Manuel Peña,[1] this corrido perfectly exemplifies the genre as vehicle for expressing the Mexican side of the inter-ethnic clash. And it shows that heroic corridos of the era were not limited to the border region.

“It depicts a larger-than-life hero who either defeats the Anglos or goes down before overwhelming odds,” wrote Peña in the October 1992 issue of Aztlán: A Journal of Chicano Studies. “This corrido, if its origin can ever be pinpointed, may yield proof that the Californios—themselves experiencing pressure from the Anglos—were in the vanguard in realizing this important folk music genre.”

“It depicts a larger-than-life hero who either defeats the Anglos or goes down before overwhelming odds,” wrote Peña in the October 1992 issue of Aztlán: A Journal of Chicano Studies. “This corrido, if its origin can ever be pinpointed, may yield proof that the Californios—themselves experiencing pressure from the Anglos—were in the vanguard in realizing this important folk music genre.”

In these heroic corridos, the inter-cultural conflict is often dramatically played out in the dialogue between the protagonist and his enemies, especially the hated “Rinches.” In the Murrieta ballad, the protagonist admits killing thousands in revenge, but he explicitly decries the “unjust” laws that label him a bandido. Instead, he sees himself as the prototypical Robin Hood, robbing from the “avaricious rich” and “fiercely defending the poor and simple Indian.”

A los ricos avarientos, yo les quité su dinero.

Con los humildes y pobres, yo me quité mi sombrero.

Ay, que leyes tan injustas por llamarme bandolero.

From the avaricious rich, I took their money.

With the humble and the poor, I take off my hat.

Oh, what unjust laws for labeling me bandolero.

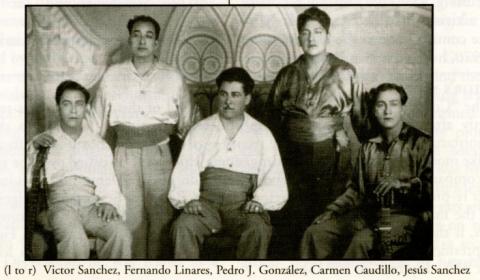

The Frontera Collection has three versions of the corrido of Joaquín Murrieta recorded in two parts on 78-rpm records, all by some incarnation of Los Madrugadores, or The Early Risers. The 1934 recording on the Vocalion label was also released on Columbia with somewhat better fidelity. A slightly different version (same lyrics, different arrangement) was released on Decca by Los Hermanos Sánchez y Linares, composed of the two original members of Los Madrugadores, the brothers Jesús and Víctor Sánchez, along with Fernando Linares. The group has its own compilation CD on Arhoolie, Pedro J. González and Los Madrugadores, 1931–1937 (Arhoolie 7035), which features the two-part Murrieta corrido.

As if to extend the Murrieta narrative, a second drama unfolded related to Pedro Gonzalez, the leader of Los Madrugadores. The group had a popular predawn radio show in Southern California, which served as an alarm clock for Mexican field workers during the Great Depression. The show also featured commentary by González, who spoke out against the mass deportations of Mexicans at that time. In a case of life imitating art, the corrido’s message of injustice was reinforced when González was himself sent to San Quentin prison on trumped-up rape charges. That was in 1934, the very year Los Madrugadores recorded the song.

As if to extend the Murrieta narrative, a second drama unfolded related to Pedro Gonzalez, the leader of Los Madrugadores. The group had a popular predawn radio show in Southern California, which served as an alarm clock for Mexican field workers during the Great Depression. The show also featured commentary by González, who spoke out against the mass deportations of Mexicans at that time. In a case of life imitating art, the corrido’s message of injustice was reinforced when González was himself sent to San Quentin prison on trumped-up rape charges. That was in 1934, the very year Los Madrugadores recorded the song.

The musician/activist was released in the early 1940s after appeals by two Mexican presidents and huge public protests organized principally by his wife, Maria. He was deported to Mexico and settled in Tijuana, where he immediately reassembled a band and took again to the airwaves. Undaunted, González continued to use his radio show to speak out against injustice, blasting broadcasts across the border for the next 30 years.

Eventually, González was permitted to return to the United States. In 1985, when he was 90, PBS aired a documentary on his life and career, ''Ballad of an Unsung Hero,'' which was later turned into a TV movie, "Break of Dawn" (1988), starring Mexican folk singer Oscar Chavez. Ten years later, González passed away at a convalescent home in Lodi, California. The headline of his obituary, which ran in the New York Times on March 24, 1995, called him, appropriately, a “folk hero.” He was 99.

It’s not hard to see how such harrowing stories would become the stuff of legend and how ballads about them would be passed down through generations. Peña notes that Joaquín Murrieta “actually came to the attention of modern scholarship in the 1970s” after Strachwitz included a version of the song in a corrido compilation (Arhoolie LP-9004, 1974).

It’s not hard to see how such harrowing stories would become the stuff of legend and how ballads about them would be passed down through generations. Peña notes that Joaquín Murrieta “actually came to the attention of modern scholarship in the 1970s” after Strachwitz included a version of the song in a corrido compilation (Arhoolie LP-9004, 1974).

The revival of interest in the defiant Murrieta was also fueled by the surging political and cultural awakening of the Chicano Movement, which embraced him as a symbol of resistance and rebellion against the Anglo establishment. At UC Berkeley in the early 1970s, for example, a Chicano student organization, Frente de Liberación del Pueblo, established a unique Chicano student dorm named Casa Joaquín Murrieta. The rebel’s famous image was emblazoned on the building, which also served as the activist group’s base of operation. (Disclosure: I was a member of Frente and edited the group’s newspaper at the time.)

“Corridos have an amazing life,” says Strachwitz. “They are written about events that took place decades ago, but they still resonate with people as if they were hearing them for the first time.”

In the next installment: Historic two-part corridos.

--Agustín Gurza

Additional reading:

The Mexican Corrido: Ballads of Adversity and Rebellion, Part 1: Defining the Genre

The Mexican Corrido: Ballads of Adversity and Rebellion, Part 3: Two-Part Corridos

The Mexican Corrido: Ballads of Adversity and Rebellion, Part 4: Corridos of the Mexican Revolution

[1] “Música fronteriza / Border Music” by Manuel Peña. Reprinted with permission of The Regents of the University of California from Aztlán: A Journal of Chicano Studies, vol. 21, nos. 1-2, pp. 191-225, UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center.

0 Comments

Stay informed on our latest news!

Add your comment