Artist Biography: Margarita La Chaparrita - Mother, Singer, Survivor

Ed. Note: This the first in a series of biographies of artists based on information provided by family members, friends, or colleagues who contacted us by email (agurza@ucla.edu) or through our blog’s Comments sections. Most of the artists who will be featured in this series did not achieve wide success in the record business. However, their stories show how true folk music reflects the lives and culture of the common folk who make it. Without the input provided by listeners who reached out to us, their stories would most likely never be formally documented. Please continue to share your knowledge and family histories with us!

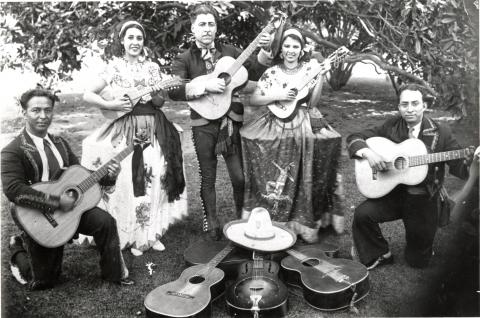

The recording career of Margarita La Chaparrita was modest and short-lived but remarkable, nevertheless. After struggling through a series of traumatic relationships and raising seven children with meager resources, the late-blooming performer decided to start her own band in the midst of middle age, when most other mothers are winding down to retirement.

The recording career of Margarita La Chaparrita was modest and short-lived but remarkable, nevertheless. After struggling through a series of traumatic relationships and raising seven children with meager resources, the late-blooming performer decided to start her own band in the midst of middle age, when most other mothers are winding down to retirement.

“I remember always hearing her singing in her kitchen while she was making dinner and I knew that music was a secret passion of hers,” said her daughter, Diana Benavides-Arredondo. “Once she finished raising all her children, she went for it. When she was in her late 40s and found herself an empty-nester, she started a small Mexican band and Margarita La Chaparrita y Su Conjunto was born.”

Her musical career, both as amateur and professional, spanned some 20 years, starting in the mid-1970s through the mid-‘90s. But commercial success in the record industry eluded her; the singer’s total discography includes at most half a dozen singles recorded in the 1980s, her daughter says. Still, she was active and well-known within San Antonio’s tight-knit musical community. She made the rounds of local lounges, nightclubs, and restaurants, selling her records wherever she played. She was frequently featured as a local celebrity at popular festivals, such as the “Diez y Seis Parade” for Mexican Independence Day and the city’s historic Battle of Flowers Parade.

“She was a very strong, determined woman,” says Benavides-Arredondo, a retired school district employee who still lives in San Antonio. “Although she only had minor success, I knew this made her very happy. I always admired her nerve to get up on stage and sing in front of an audience.”

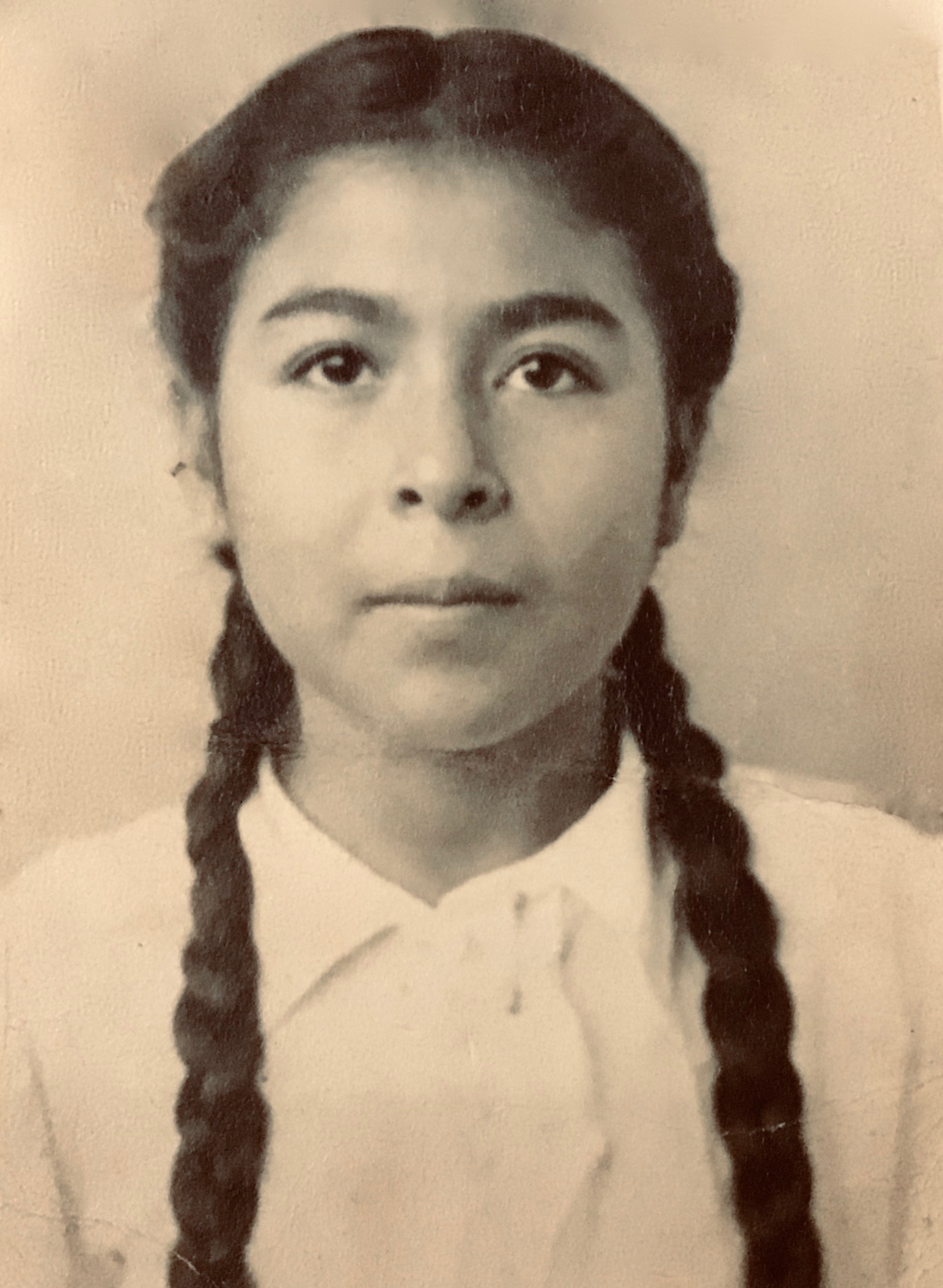

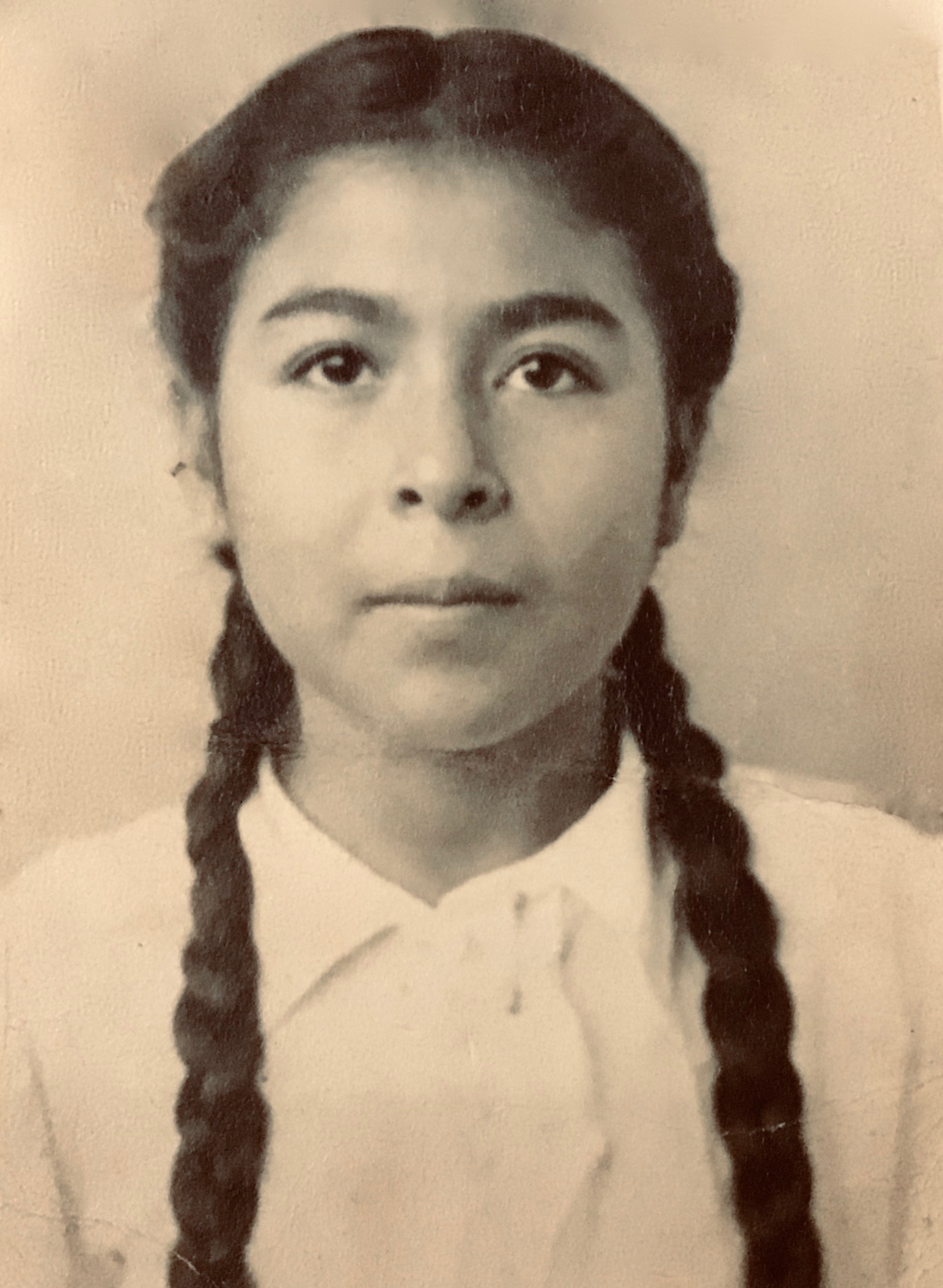

La Chaparrita was born Margarita Montoya on February 24, 1936 in Crystal City, Texas, a town of less than 10,000 people located about an hour’s drive from the Mexican border. She was raised in the city, also known as the Spinach Capitol of the World and the birthplace of La Raza Unida Party in the early 1970s. She started singing by the time she was eight years old. She never finished grade school.

Montoya’s early life was troubled and tragic. Her mother died when she was still a toddler, and her father was shot and killed a few years later, according to her daughter. Margarita and her sister, Santa, were then raised by their paternal grandparents, who were “not so very nice,” Benavides-Arredondo states.

Montoya was 18 when she became a bride. It would be the first of three marriages, all to men who were abusive alcoholics, according to her daughter. She had a total of seven children, six with her first husband, though one son died at a young age. She gave birth to her daughter, Diana, during an affair with a married man while separated from her first husband. She ultimately returned to her husband and Diana blended in comfortably with her half-siblings.

Daily life was difficult, however. Montoya collected welfare and food stamps when her kids were little, and she supplemented her income by working as a waitress in a Crystal City bar. Yet, the household was always rich with the aroma of her homemade flour tortillas and the joyful sounds of music.

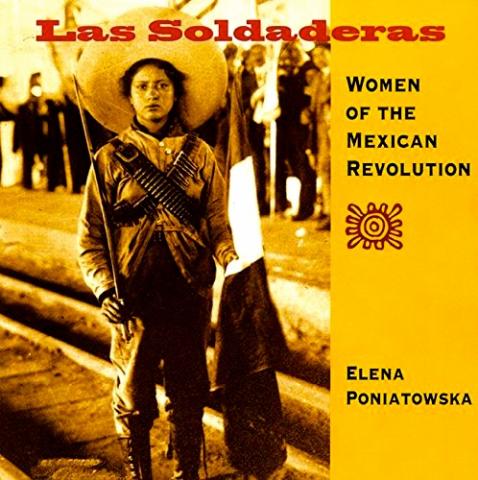

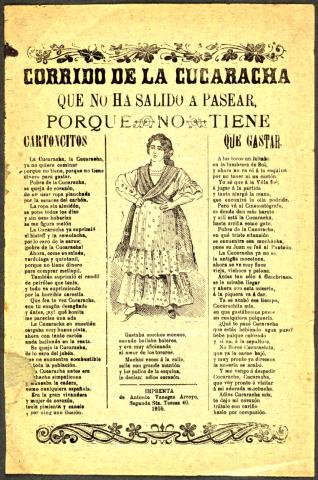

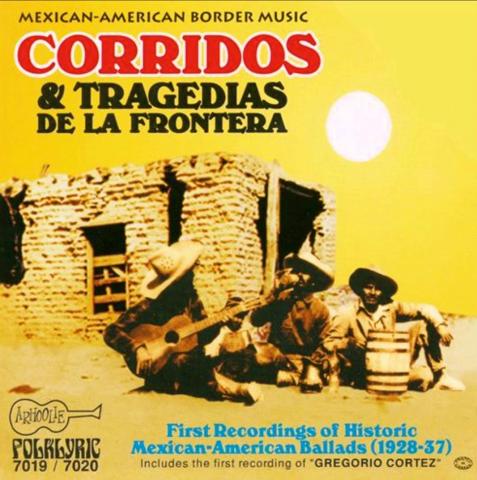

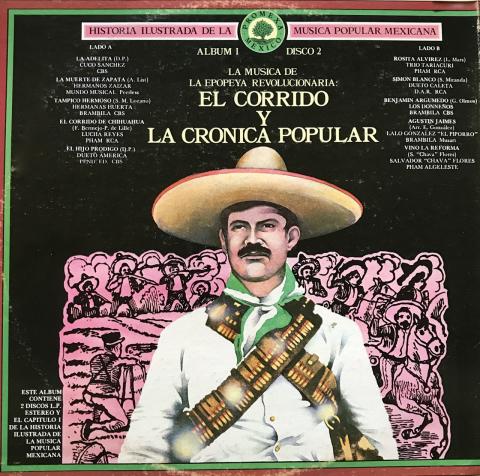

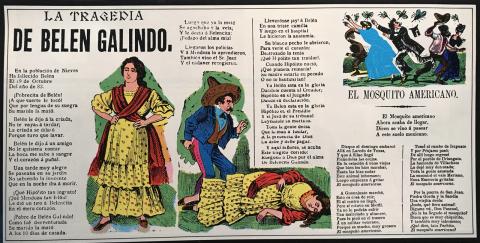

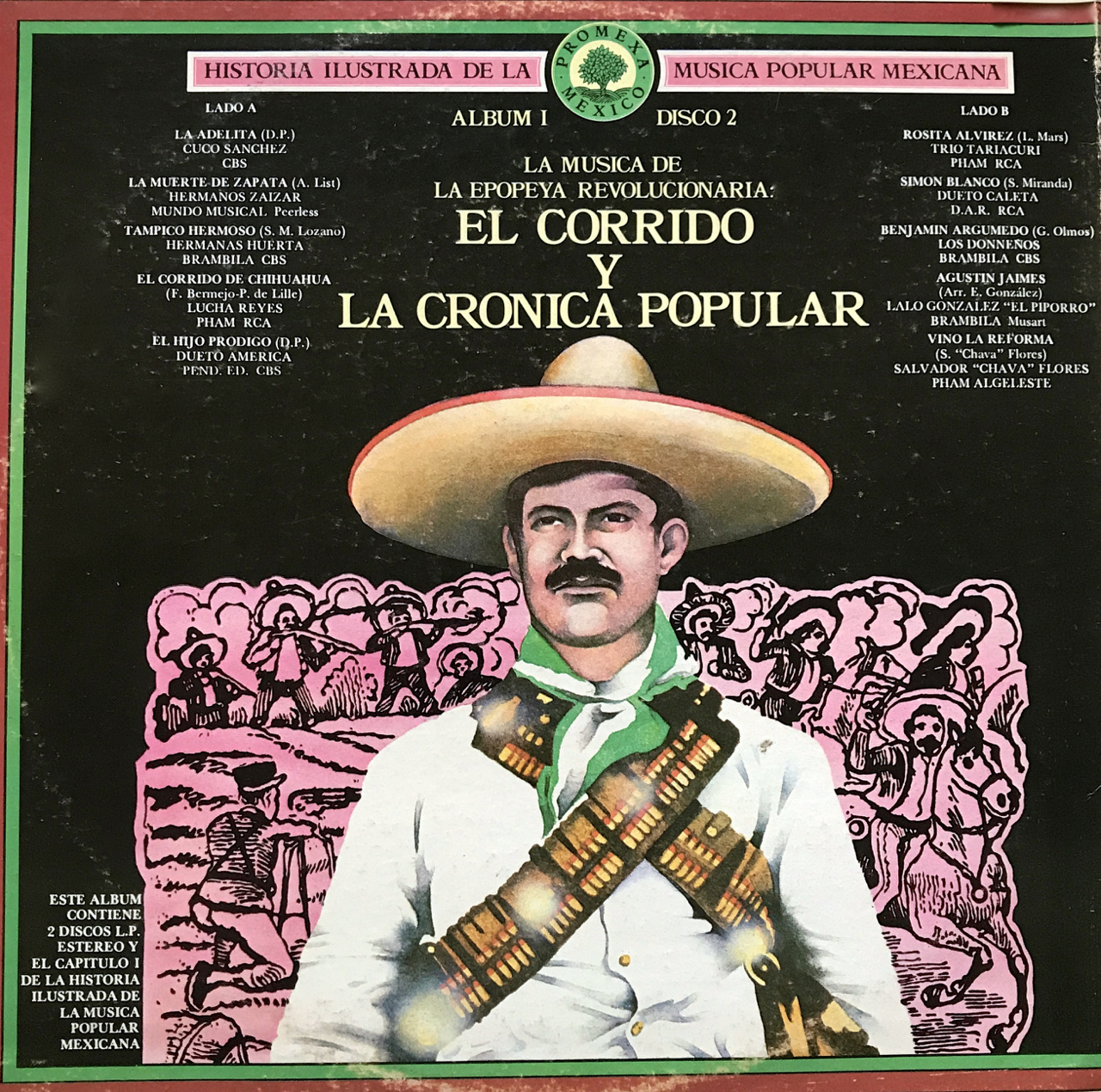

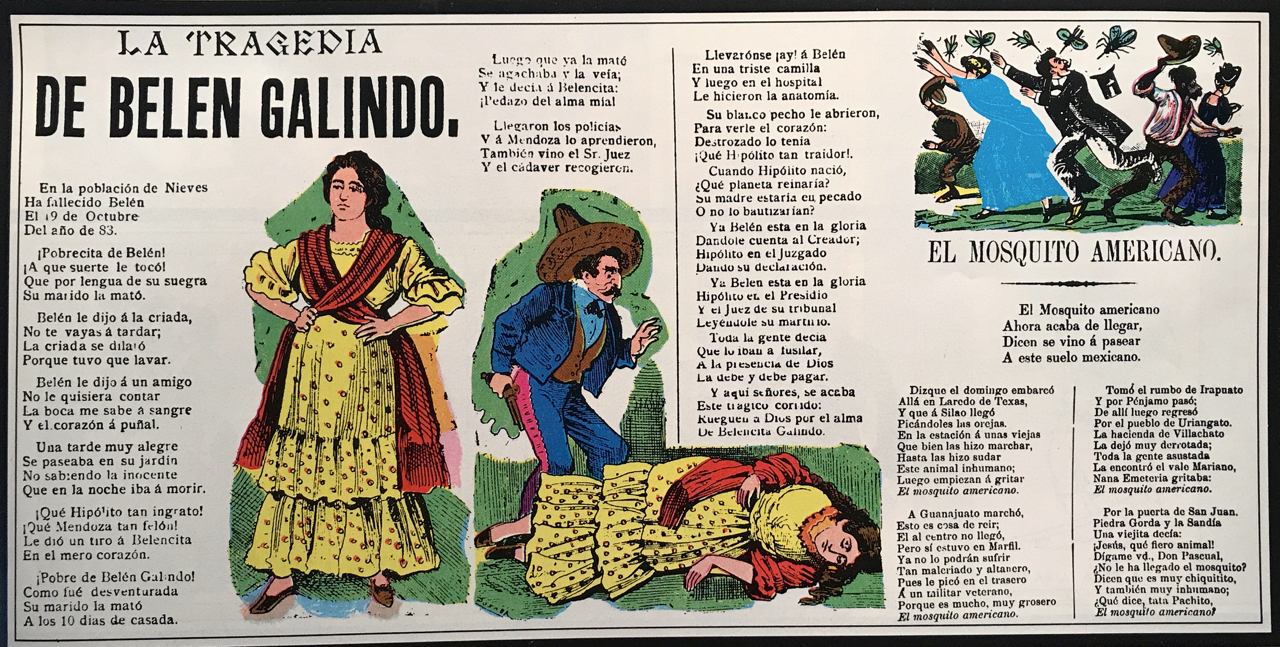

“There was always music in the house!” says Benavides-Arredondo. “The radio was usually on when we got home from school, while she made dinner, always on her favorite Tejano stations (KCOR or KUKA). She liked corridos, polkas, rancheras, and cumbias. She liked music that told a story.”

Montoya finally divorced and left Crystal City, her brood in tow. The family moved to San Antonio to start a new life, recalls Benavides-Arredondo, who was approximately six years old at the time. As a single mother, Montoya struggled to get established, moving her family for a time into government-subsidized housing.

Montoya’s second marriage also ended in divorce after 13 years. She then met and married her third and final husband, Julio Perez, an Army sergeant whom she considered “the love of her life." After just three years, he committed suicide while stationed in Germany.

Montoya’s second marriage also ended in divorce after 13 years. She then met and married her third and final husband, Julio Perez, an Army sergeant whom she considered “the love of her life." After just three years, he committed suicide while stationed in Germany.

In the early 1980s, soon after her husband’s death, Montoya poured her energies into her career, forming her band and making her first recordings. Keeping her late husband’s surname, she appeared in her promotional materials as Margarita Perez.

Despite all the instability, Montoya managed to maintain her sense of humor, and her determination.

“Considering she only had a third-grade education, she did pretty well for herself,” recalls her daughter. “[She was] not rich by any means, but she managed to own a house and occasionally a new car. Somewhere along the line, she taught herself to read and write English, and she learned to pay her bills and tried her best to balance her checkbook.”

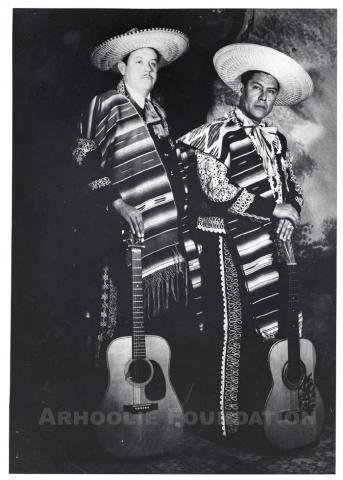

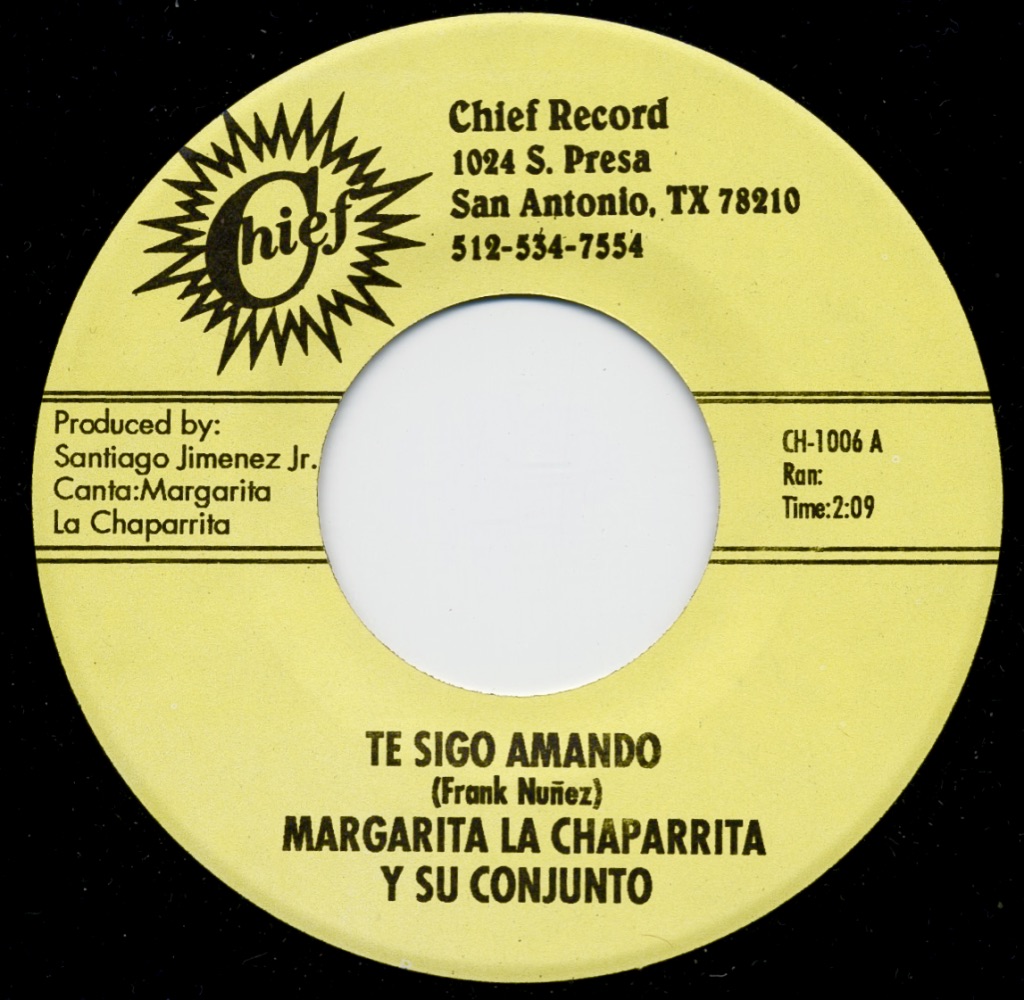

Montoya was in her mid-40s when she started her band, Margarita La Chaparrita y Su Conjunto. She also performed with other groups and mingled with prominent Mexican-American artists in the active San Antonio music scene. The producer on her Chief Records single is Santiago Jimenez, Jr. of the Tex-Mex dynasty that includes Santiago Jimenez Sr. and the world-renowned accordionist Flaco Jimenez.

“We were not aware of the recording contract,” her daughter recalled. “She just showed up one day with a ‘complimentary’ 45-rpm of her recording and gave it to me as a souvenir. I was truly surprised and impressed she had actually recorded a record. I don't think she even had a manager.”

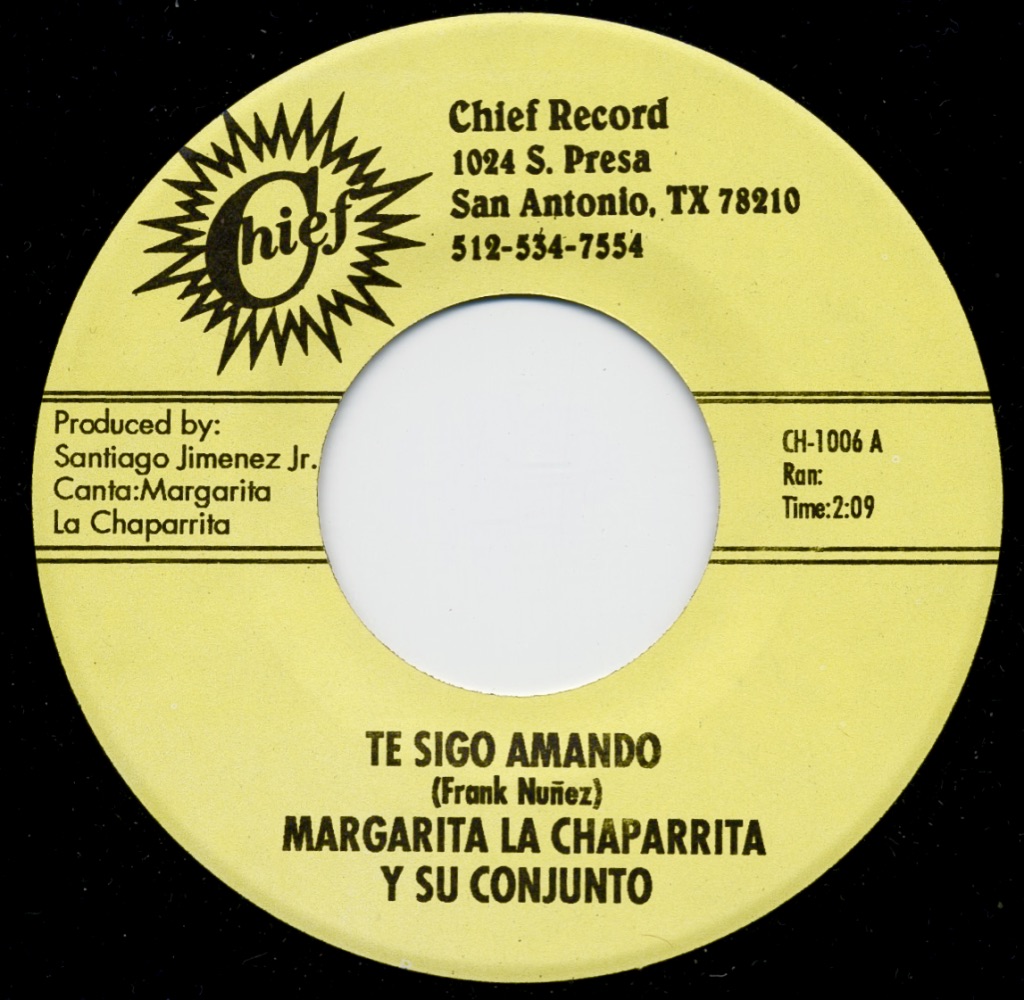

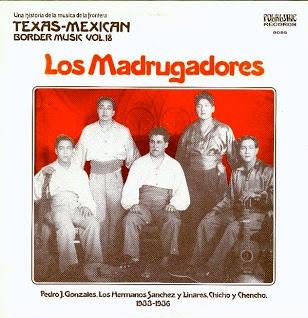

The Frontera Collection holds only two singles by the singer, whose stage name, La Chaparrita, roughly translates as “little shorty.” Both releases are on relatively obscure labels that were based in San Antonio, Texas. On Chief Records, she is accompanied by her own band on two numbers written by Frank Nuñez: “Te Sigo Amando” backed by “Eres Todo Para Mi.” And on TVT (an imprint of Custom Recordings), she performs with El Conjunto de Eddy Torres on two traditional rancheras: “Delante de Mi” by Dolores Ayala (credited as Dolores Mata) and “Laguna de Pesares” by José Alfredo Jiménez.

The Frontera Collection holds only two singles by the singer, whose stage name, La Chaparrita, roughly translates as “little shorty.” Both releases are on relatively obscure labels that were based in San Antonio, Texas. On Chief Records, she is accompanied by her own band on two numbers written by Frank Nuñez: “Te Sigo Amando” backed by “Eres Todo Para Mi.” And on TVT (an imprint of Custom Recordings), she performs with El Conjunto de Eddy Torres on two traditional rancheras: “Delante de Mi” by Dolores Ayala (credited as Dolores Mata) and “Laguna de Pesares” by José Alfredo Jiménez.

For a period of time in 1982, Montoya performed every Sunday on a live, hour-long broadcast on KFHM-AM (“La M Grande”), which had switched to a Tejano/Latino format four years earlier, reflecting the growing popularity of regional music at the time.

For a period of time in 1982, Montoya performed every Sunday on a live, hour-long broadcast on KFHM-AM (“La M Grande”), which had switched to a Tejano/Latino format four years earlier, reflecting the growing popularity of regional music at the time.

Margarita La Chaparrita received many awards and trophies for her performances over the years, and some made the local newspaper. In October 1978, for example, the San Antonio Express-News reported she had won first place for her Diez y Seis Parade performance. It marked the eighth time in five years that she had been recognized by the Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center with a trophy, ribbon, or certificate for her vocal performances during the annual festivities.

Nothing gave her greater satisfaction, however, than performing for seniors at charitable events sponsored by the Royal Palace Ballroom in San Antonio’s southside barrio. In a 1991 Express-News story, La Chaparrita and her band were mentioned as one of the venue’s “most popular conjuntos.” At the time, the paper reported, she had 12 grandchildren and five great-grandchildren.

By the end of the decade, Margarita La Chaparrita had retired from music. She passed away of ovarian cancer on April 23, 2016, and is buried at Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery, along with her military husband. She left behind a notebook of hand-written lyrics to songs she had written.

As with many other barrio artists who labored in relative anonymity, Montoya’s recordings will be preserved for posterity in The Frontera Collection. Recently, Benavides-Arredondo contacted us through this website to express gratitude on her mother’s behalf.

As with many other barrio artists who labored in relative anonymity, Montoya’s recordings will be preserved for posterity in The Frontera Collection. Recently, Benavides-Arredondo contacted us through this website to express gratitude on her mother’s behalf.

“My mother was a little vain and she would have loved to know she was included in this important archive,” Benavides-Arrendondo said. “She would have been showing it off to all her friends and family!”

– Agustín Gurza

Blog Category

Tags

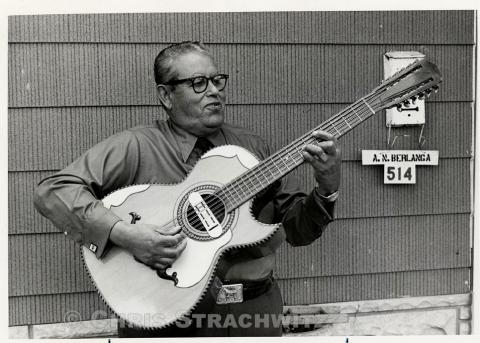

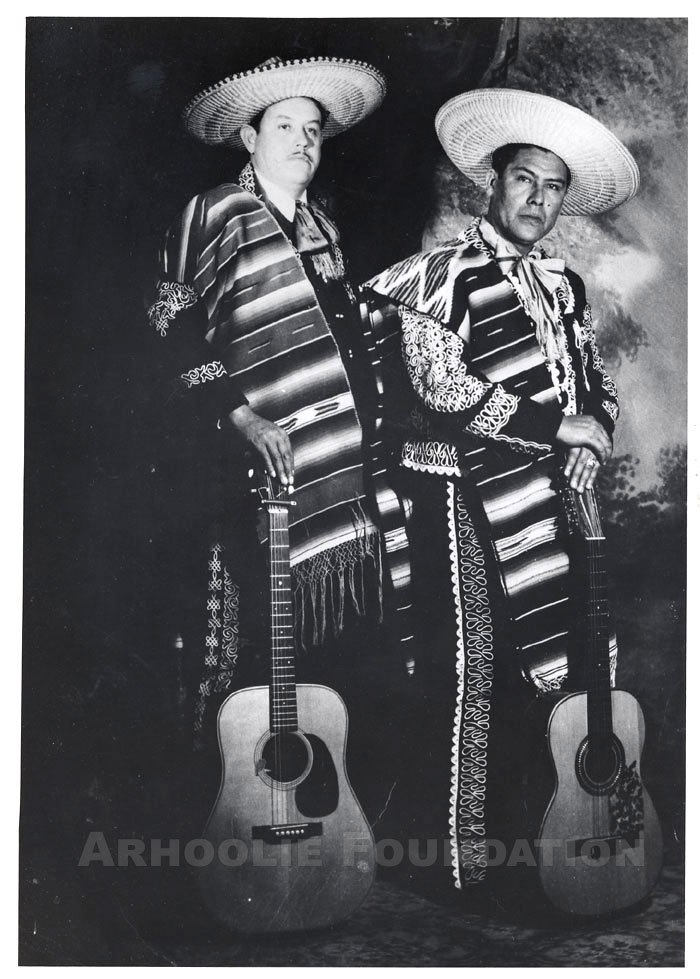

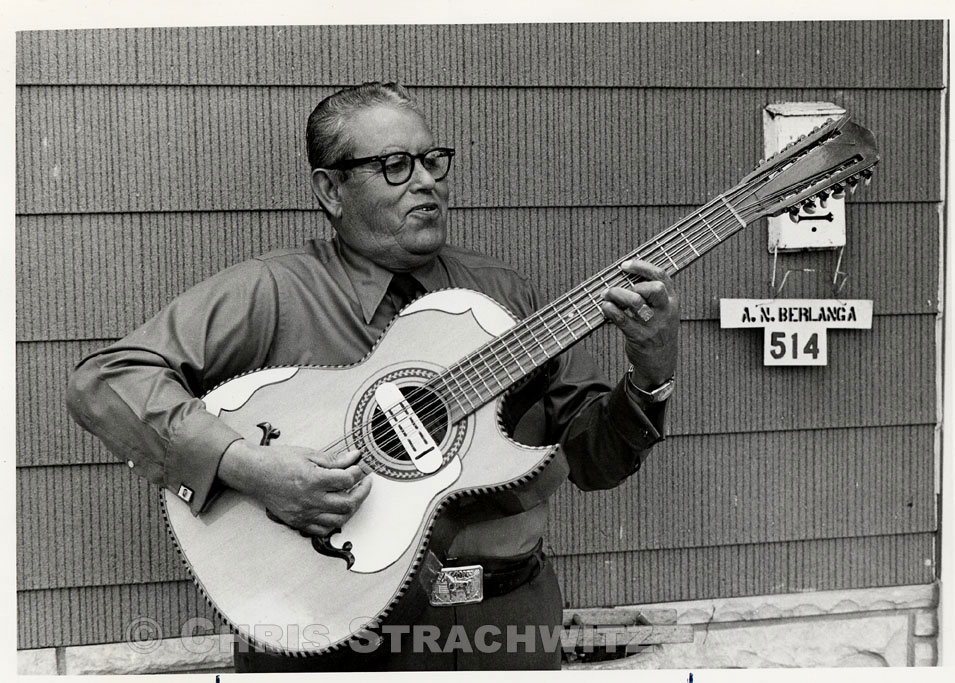

Images