Coronavirus Corridos: Tales of the Pandemic

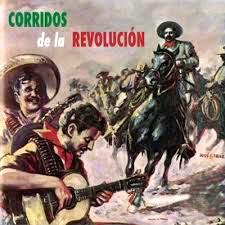

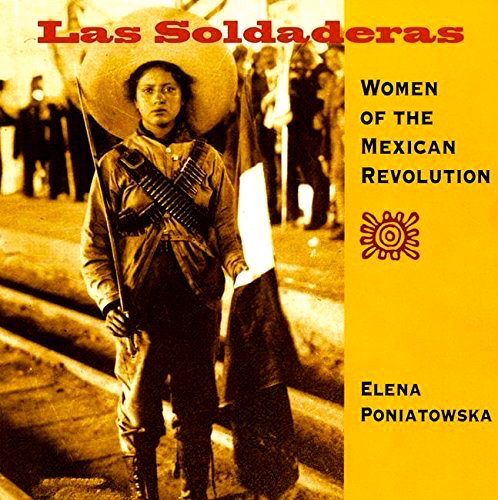

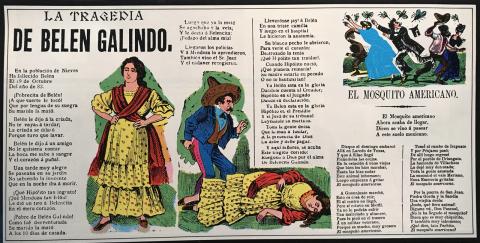

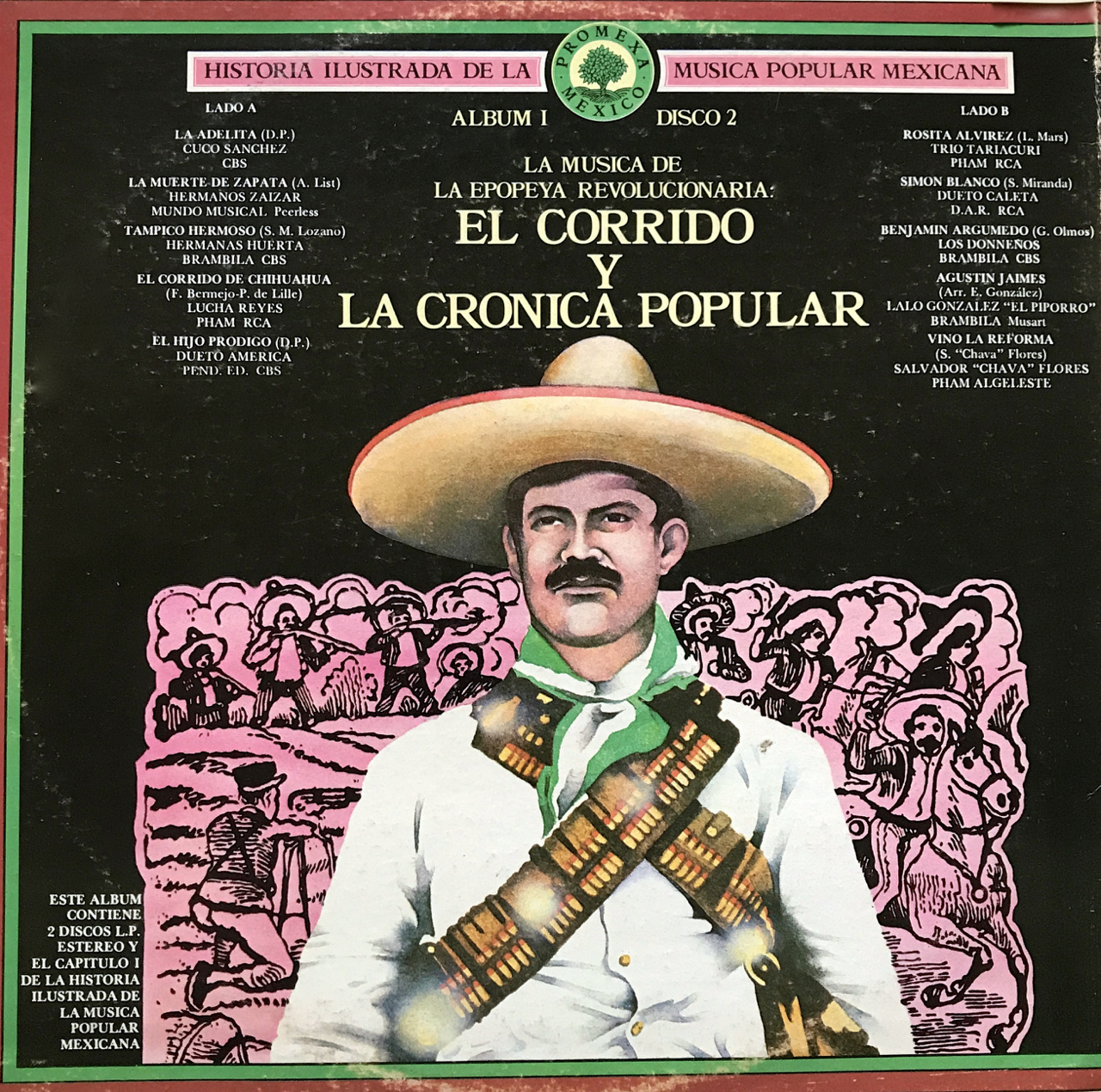

The coronavirus pandemic has all the makings of a corrido, the historic narrative ballad of Mexico. The public health crisis has brought fear, death, tragedy, and social conflict – all of which have been subjects of this song form since before the Mexican Revolution.

The coronavirus pandemic has all the makings of a corrido, the historic narrative ballad of Mexico. The public health crisis has brought fear, death, tragedy, and social conflict – all of which have been subjects of this song form since before the Mexican Revolution.

Not surprisingly, songs about the global contagion have quickly sprouted and spread among corrido fans like, indeed, a virus. But the viral topic has also jumped genres, cropping up in various styles, including reggaeton, salsa, mariachi, ballads, and folk.

This musical trend, like the pandemic, has gone global, with videos (predominantly on YouTube) coming from Vietnam, the Dominican Republic, and China. Equally diverse is the stature of artists recording virus-oriented songs, from superstars to rising stars to total unknowns.

In the U.S., a parody of The Knack’s “My Sharona” became “My Corona,” by Zubin Damania, a Stanford-trained physician and musician, a.k.a. ZDoggMD. And rock star Jon Bon Jovi has created a crowd-sourced composition, “Do What You Can,” with verses submitted by fans as co-writers. Meanwhile in Panama, famed singer-songwriter Ruben Blades posted a new song with a stirring call for social solidarity, featuring video clips of dozens of average people repeating the rhythmic refrain, “Pa-na-má.”

The phenomenon has been widely documented by media outlets in both languages, including Billboard, the BBC, the Bay Area’s KQED, and Mexican national news outlet Milenio.

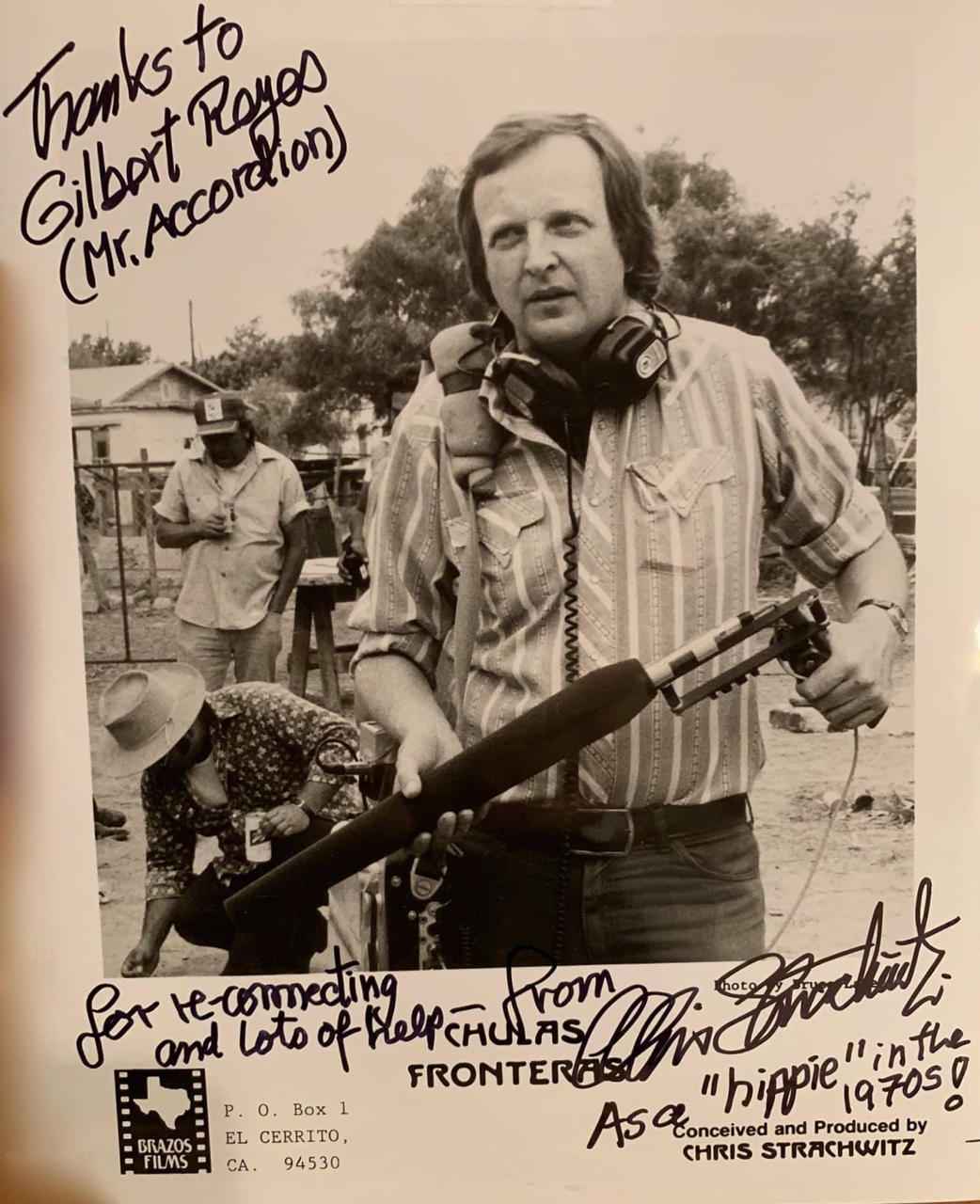

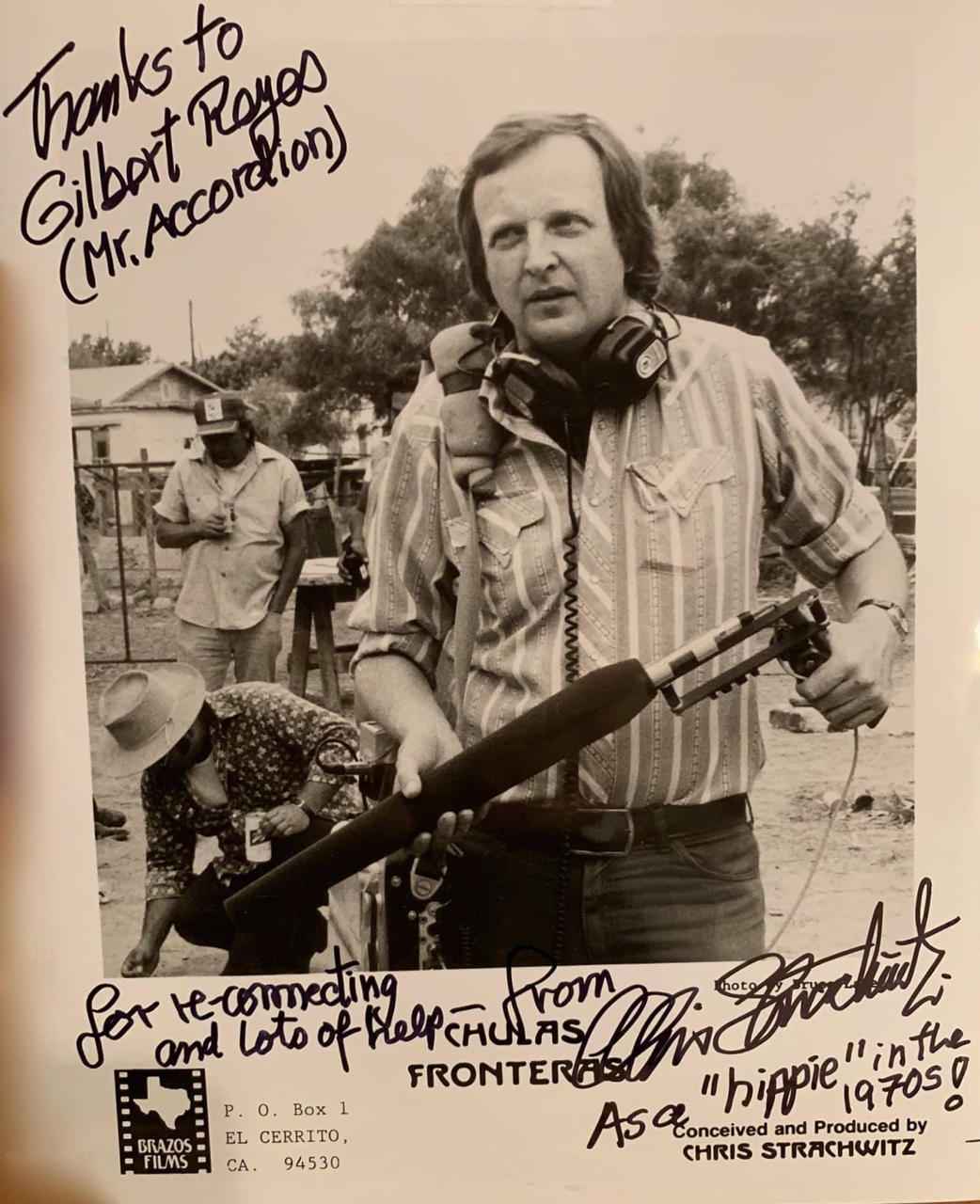

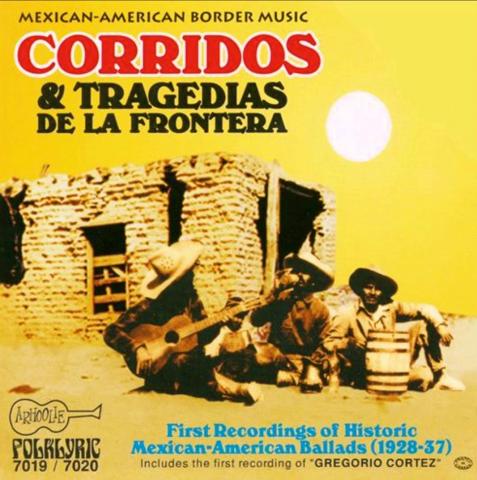

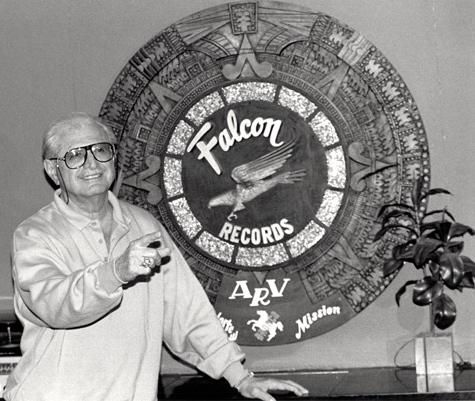

I first learned about the trend from a Facebook post by producer Chris Strachwitz, founder of the Frontera Collection and longtime collector of recorded corridos. Strachwitz had discovered a YouTube video titled “Un Corrido Al Coronavirus,” written and performed by Los Potrillos de Turicato, a group who named themselves after their hometown in Michoacán, southwest of Morelia, the state capital. The town, in turn, gets its name from a parasite, a soft-bodied tick, that plagues primarily hogs and cattle but can cause relapsing fever in people. Perhaps the home turf of Los Potrillos (The Colts) gave them a grassroots feel for the zoonotic diseases that jump from animals to humans.

The group posted its video on the YouTube page for Turi Records, which features folk culture of the region, known as Tierra Caliente. The promoters aim “to help new musical talent and help maintain music styles featuring string instruments - violín, tololoche, vihuela, and bajo quinto,” among others.

There are scores of videos featured on the site, including a jaw-dropping number of songs dealing with the novel coronavirus, warning about its devastating consequences and urging listeners to practice social distancing and frequent hand-washing.

The Strachwitz post prompted a brief, side discussion about whether the song by Los Potrillos truly qualified as a corrido, a genre that, in its purest form, must contain certain elements. As I described in the first installment of my series on the genre, “The Mexican Corrido: Ballads of Adversity and Rebellion,” those elements include: A formal opening, or call to the public, by the corridista; a specific sense of time and place; a tragic conflict involving a protagonist who often faces death; and a formal farewell by the corridista.

Strachwitz asked his Facebook followers for an English translation of the lyrics, which I provided. Once he read them, he decided the song did not strictly qualify as a corrido, although he still liked it. The truth is, contemporary corrido composers don’t feel obliged to stick religiously to the classic structure. Yet, one element remains at the core of corridos of all epochs: the heroic and often tragic conflict against adversity.

That’s true for the song by Los Potrillos, as evidenced by the opening verse:

Natural disasters are natural topics for corridos, highlighting the struggle of humans against uncontrollable, lethal forces. Scores of corridos have been written over the years about earthquakes, hurricanes, floods, and volcanic eruptions, as I explained in my two-part series about “Disaster Songs,” published in 2016 as Part 1 and Part 2. I was surprised to find, however, that songs about fatal epidemics are rare, based on a search of our database for this article, using multiple terms, such as disease, illness, contagion, epidemic, virus, and “gripe,” Spanish for flu.

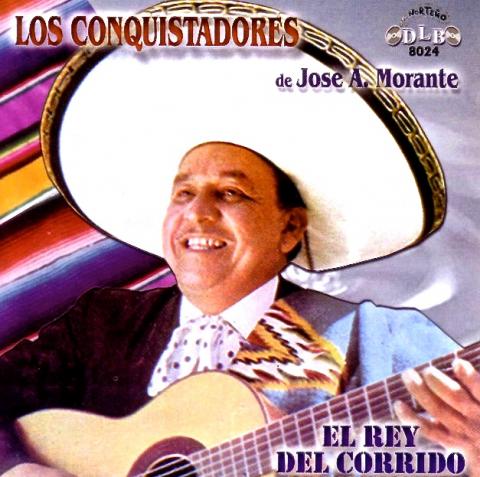

I did come across one song, “Tragedia de los Caballos” by Mariachi Conquistadores, about a viral epidemic that swept through horse herds in the early 1970s. Written by prolific composer José A. Morante, the song essentially laments the loss of so many caballos, a beloved animal that figures prominently in Mexican folk music. Released as a single on the San Antonio-based Norteño label, it features the world-renowned Flaco Jimenez on accordion.

The label includes a cryptic sub-title: “Epidemia VEE.” The initials stand for the formal name of the disease, Venezuelan Equine Encephalitis, which has a death rate as high as 90 percent. The 1971 outbreak, which spread from Mexico to the U.S., was so serious that 11 states were under quarantine and a congressional hearing was held to explore efforts to contain it.

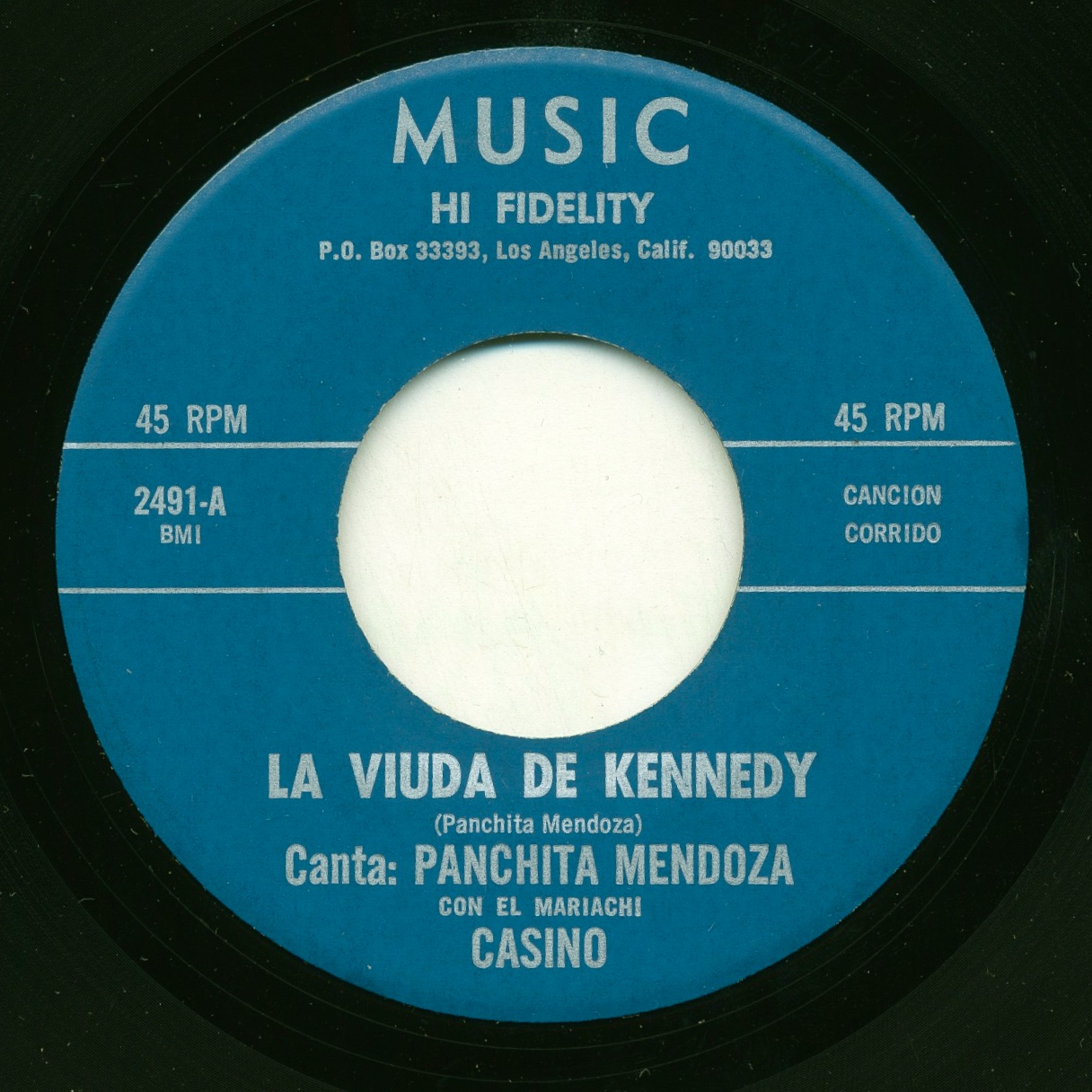

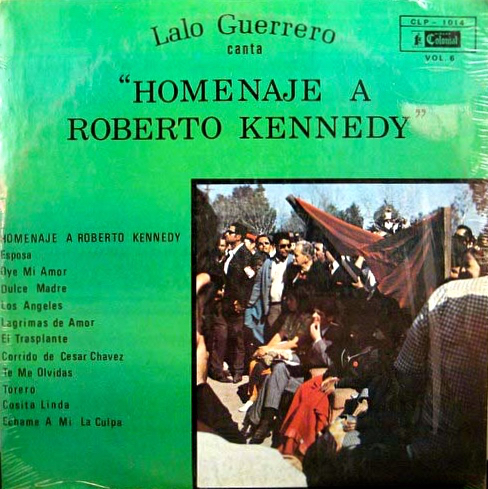

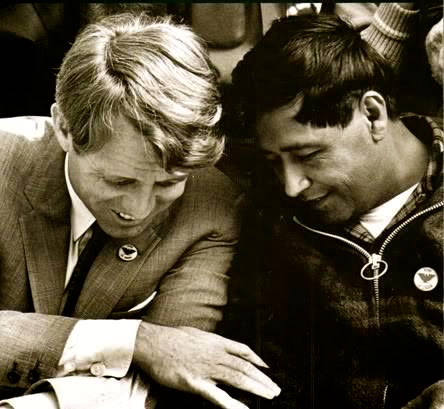

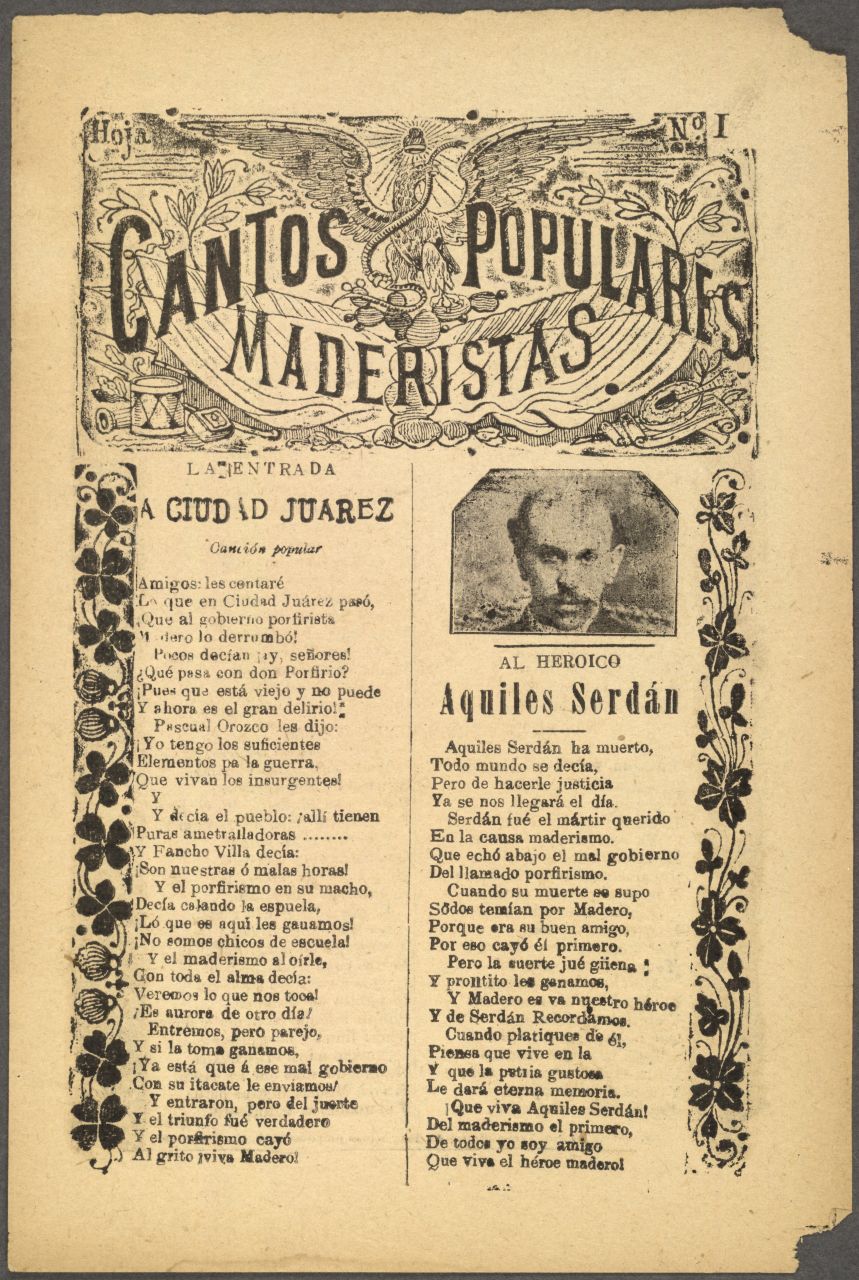

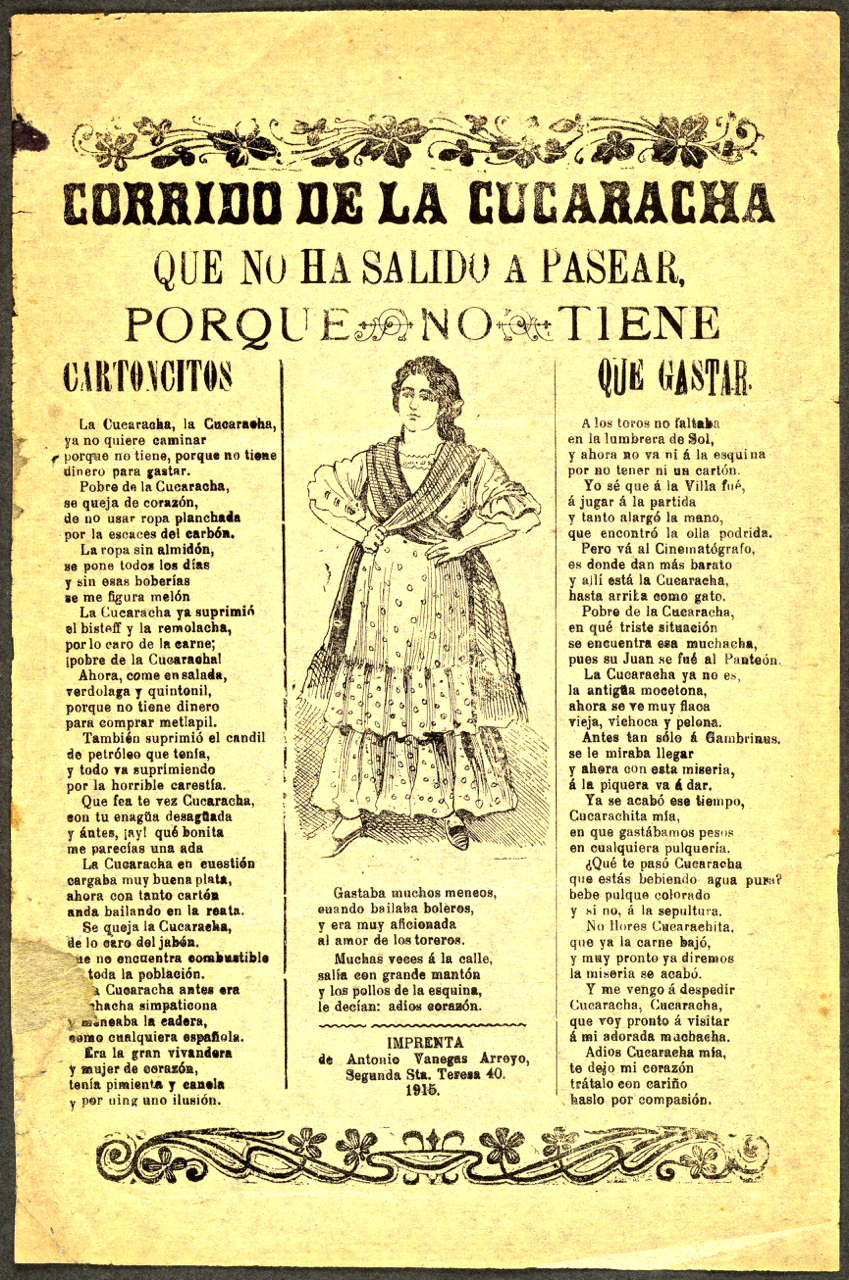

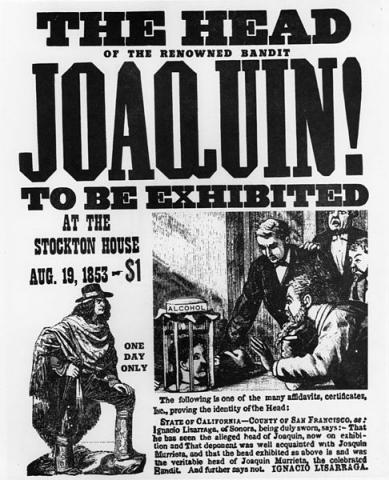

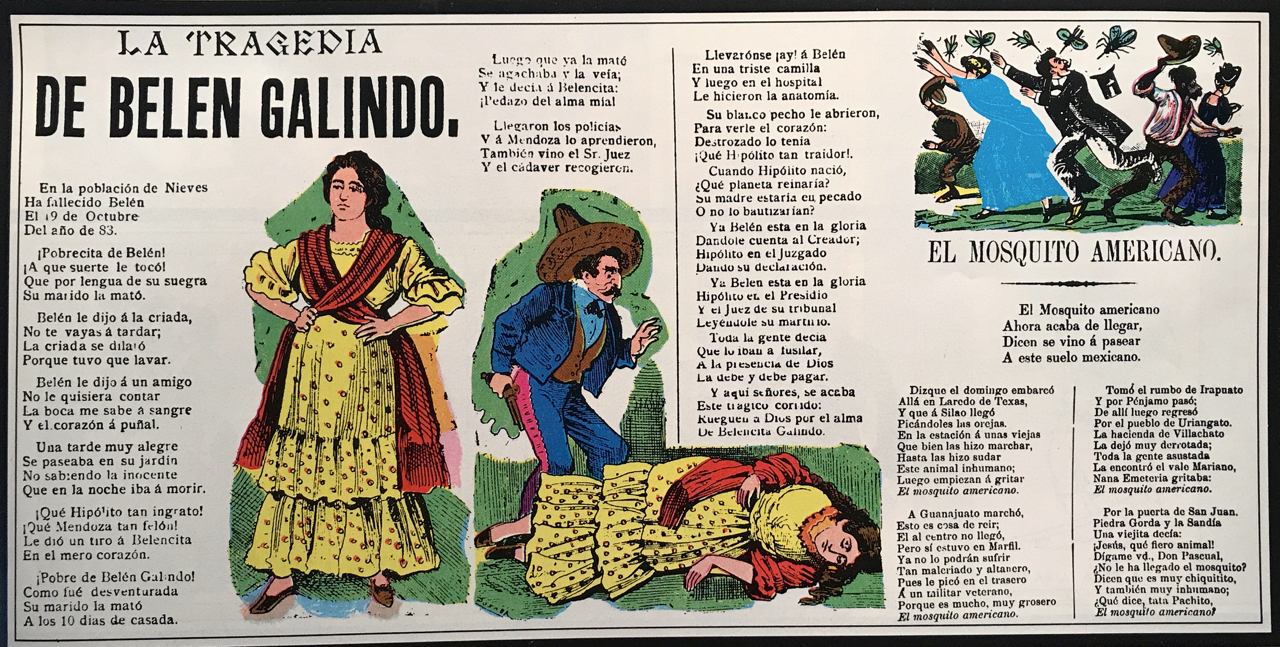

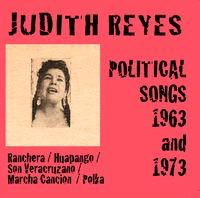

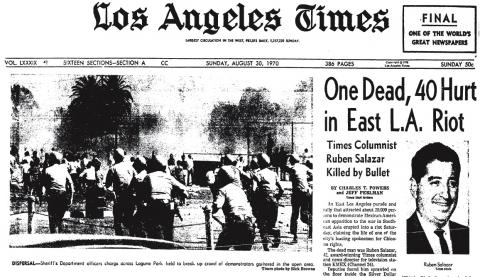

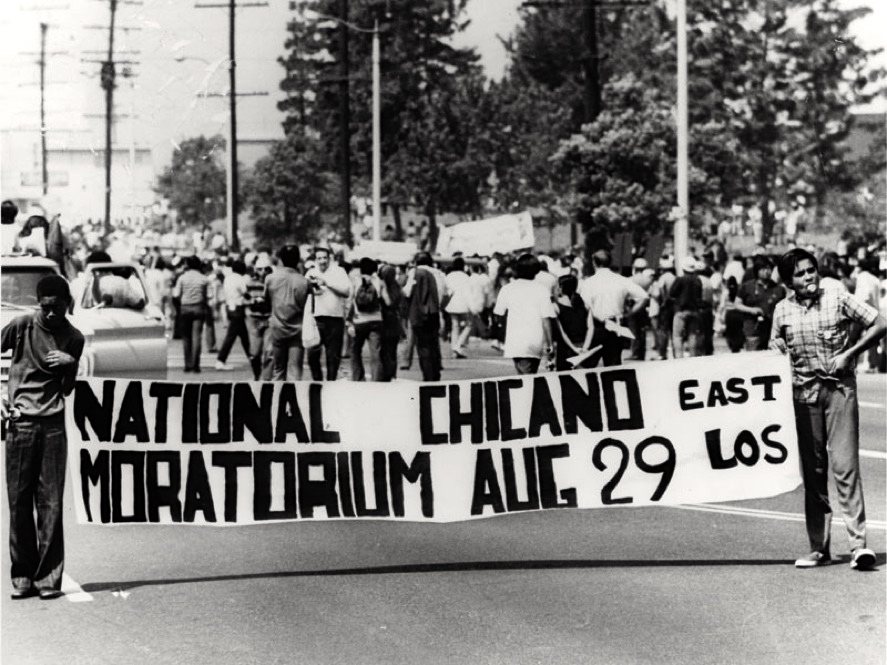

All of which I didn’t know until now. My belated awareness underscores another powerful purpose of these story-telling songs: to inform the listener of events, from major political assassinations to small-town killings. Corridos, in particular, were considered oral newspapers for poor people without access to traditional media.

The mission to inform still plays an important role for songs about the COVID-19 pandemic, be they corridos or other styles. Some have even been commissioned as public service announcements. Following are a few examples of songs in various styles, from Mexico to Panama. These artists are speaking directly to listeners, urging them to follow restrictions, inspiring them to protect their communities, and offering hope for a better day to come.

Canción del Coronavirus by Los Tres Tristes Tigres

The Three Sad Tigers are a trio from Monterey, Mexico, that specializes in satirical songs and parodies, delivered with both slapstick and deadpan humor.

Their song about the pandemic had almost 3.5 million views by early April.

But they have made two other, equally entertaining videos about the stress of having to stay home. “La Cuarentena” (The Quarantine) is a parody of the novelty hit “La Macarena,” with a new chorus, “Heeeeeey, cuarentena.” And their latest light-hearted lament, posted on YouTube April 1, is a take on “La Puerta Negra” by Los Tigres del Norte, in which they compassionately extend their mother-in-law’s quarantine for another year, just to play it safe.

They deliver their comical ode to COVID-19 in their usual format, wearing tuxedoes with bowties, facing the camera, speaking directly to their 2.16 million subscribers. The lyrics are full of witty and occasionally risqué wordplays and double entendres, with useful advice sprinkled throughout. During the verse about the importance of washing hands, the video shows the burly, bearded accordion player giving a perfect demonstration of hand-washing techniques as recommended by infectious disease experts.

The last line takes a swipe at all those hoarders of toilet paper, cutting to a clip of frantic shoppers over-loading their shopping carts. People should be informed and stay calm, the singer says, wondering why people make such a stink about bathroom tissue. (“Un rollo” can be a roll of toilet paper or a big brouhaha.) Perhaps they buy so much of it, he surmises, because nowadays whenever one person coughs, everybody gets so panicked they poop.

The group’s song got a boost when it was used in an Instagram video posted by Puerto Rican superstar Bad Bunny. The brief clip shows how the rapper and singer spends time in quarantine with his girlfriend. Among mundane activities, he is seen dancing to the cumbia, although in a clownish way that smacks of mockery.

Nota Bene: This group – whose members met as engineering students at the Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León – is not to be confused with the 1960s Venezuelan trio of the same name, or the esteemed novel by Guillermo Cabrera Infante, the Cuban author and screenwriter (Vanishing Point, 1971, and The Lost City, 2005).

Corrido de Nayarit by Martin y Malena with the Mariachi Tapatío

A state official, quoted by a Mexican cable TV network, said the PSA was aimed at people who still don’t take the virus seriously. The creators of the corrido-turned-jingle hope to convince people that “this is real, it’s not fiction, it’s not a lie, it’s a reality that can affect us all.”

El Corrido del Coronavirus by Alan y Roberto

This duo of brothers, Alan and Roberto Lara Meza, hails from Los Mochis, Sinaloa, and is now based in Phoenix, Arizona. They are admirers of Los Tigres del Norte and describe their music as “old school… with a modern touch.”

You can hear the old school in the high-pitched harmonies that are typical of norteño duet vocals. The tune’s structure and phrasing, however, smacks of the new narco-corridos coming from L.A., although these siblings clearly convey a Christian vibe. Their song delivers a positive message, “a call for calm, community, faith, and brotherhood.”

But what most drew my attention was the skilled musicianship of the backup trio. The guy in the Ferrari tee-shirt looks cool while killing it on the upright bass. Now watch the bearded player on the left with the white, 12-string guitar. He is plucking the soul out of it, making it sound like the traditional bajo sexto though the instrument is made by Takamine, based in Japan. Unlike the bajo sexto, this guitar is amplified, with its own built-in pre-amp. A modern touch indeed.

The duo’s coronavirus corrido was featured in two Latino-oriented websites, L.A. Taco in Southern California and Latino Rebels, based in New York and owned by Futuro Media, a nonprofit founded by Mexican-American journalist Maria Hinojosa.

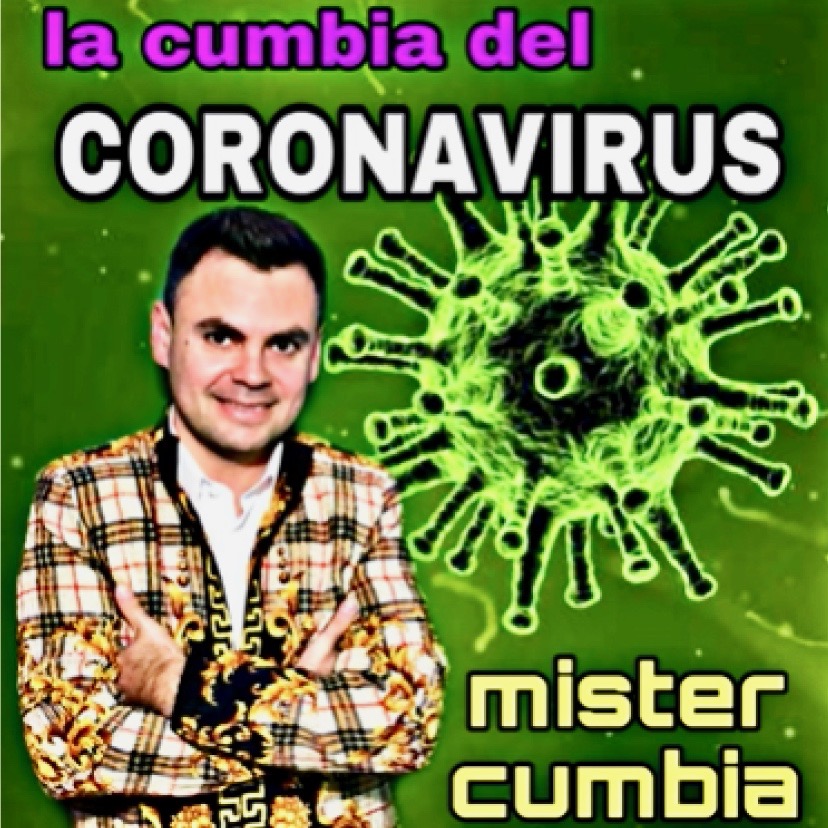

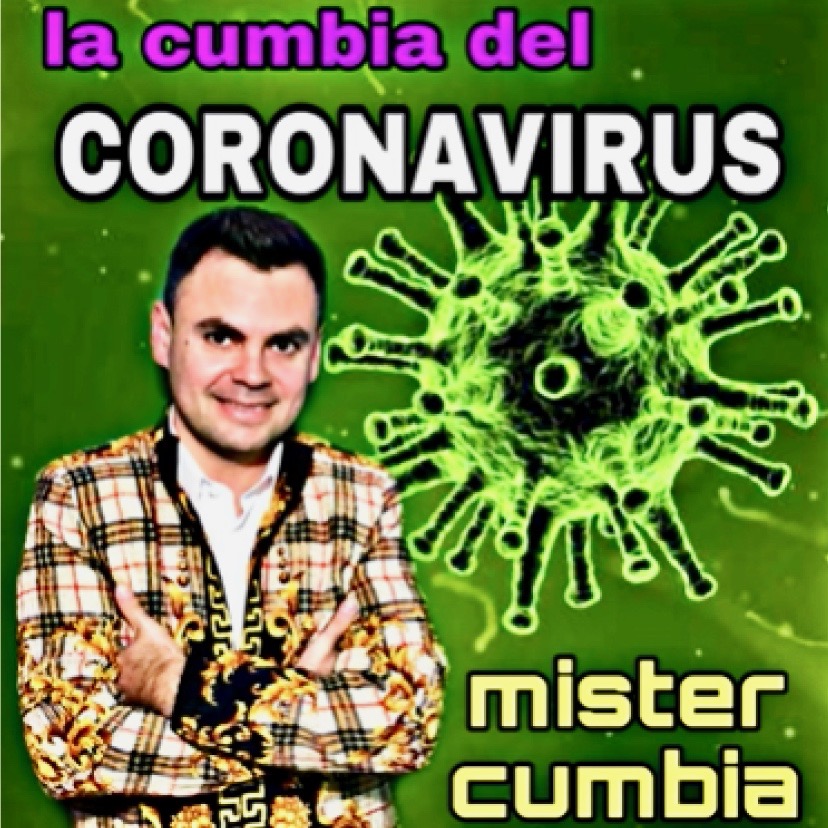

La Cumbia del Coronavirus by Mister Cumbia

Mister Cumbia has emerged as a master of musical memes in Latin America. His real name is Iván Montemayor, born in Reynosa, México in 1981, living in Virginia since 2012. He’s a composer, arranger and deejay who has a keen antenna for topics with potential to go viral. Three years ago, he had a hit, “Los XV de Rubí,” which capitalized on a social media craze surrounding a shy teen’s quinceañera that drew 30,000 unexpected guests. He’s also had viral success with songs about the daughter of the late José José, the surprising rise to fame of Oscar-nominated actress Yalitza Aparicio, and the current controversy surrounding the raffle of Mexico’s presidential plane.

All his themes ride the waves of public interest, earning him the title of el Rey de las Cumbias Virales. But when he penned his cumbia about the pandemic, Mr. Cumbia hit the jackpot. Released in January, the simple, catchy tune catapulted to the top of Spotify’s Viral 50 in Spain as well as a dozen countries across Latin America, from Mexico to Argentina, according to a March 18 article in Rolling Stone. The momentum launched the song into the music streaming service’s Global Viral 50, which has more than 1.6 million followers.

The song’s popularity was propelled by its frequent use in public service announcements. In one video, a group of doctors and nurses from a hospital in Ecuador, dressed in white and aligned in a safely spaced formation, dance to the coronavirus cumbia while using hand gestures to demonstrate proper hand-washing technique.

The deejay’s songs are created instantly, sometimes in less than two hours. And they show it. Not surprisingly, many of them sound the same. But Mr. Cumbia knows when he’s on a roll (so to speak) and has produced several songs about the coronavirus. They include: “Se Acabó el Papel” (There’s No More Toilet Paper), in which he pretends to play the sax with a roll of toilet paper around the instrument’s neck; and “Lávate Las Manos” (Wash Your Hands), a fast-talking tune in a rap/reggaeton style.

Finally, there’s “Quédate en Casa” (Stay at Home), in which Mr. Cumbia cautions people not to complain about their comfortable quarantine, in light of other people’s suffering. He reminds listeners of extreme hardships endured by people trapped involuntarily with absolutely no comforts – the miners in Chile, the children lost while exploring caves in Thailand, and the Uruguayan soccer team stranded in the Alps for weeks after a plane crash.

Good point, Mister Cumbia.

Dishonorable Mentions

Not all musical messages are positive. Some are conspiratorial and dangerous. Some don’t take the issue seriously and some take the joke too far.

La Cumbia Del Corona Virus by Jose Torres

This song stands out for its paranoid, conspiracy theories in the final verses. The coronavirus is a trick by government leaders to control the world, sings Torres, a fashionista who reads the lyrics from a device affixed to the top of his accordion. He claims presidents created this and other epidemics, like Ebola. His proof: They all suspiciously have the same symptoms, which is patently false. He ends with a conspiratorial warning: Don’t be fooled.

El Coronavirus by Marco Flores y La Jerez

These guys are having way too much fun, with their brassy banda and flashy red suits, to be bothered with social distancing. Their approach to the pandemic: Don’t worry, be happy. Some people say drunks can’t get the virus, the lyrics assert, so grab a drink and some babes and have fun to relieve the stress. The lead singer belts out the cumbia’s chorus: A mi me vale el coronavirus, porque las manos ya me lavé (I don’t care about the coronavirus because I already washed my hands.) Then he proceeds to take his sexy dancers for a spin, hand-in-hand. You could say the song is catchy, in more ways than one.

Canción del Coronavirus Ranchero by Los Chisquiados Del Monte

This silly music video has some scatological references to what happens to Americans when they run out of toilet paper. The singers, José Luis Ramos and Lety Carrillo, throw toilet paper around with abandon, then boast about a hygiene alternative used by migrants in the fields. Out in the country, they say, people use smooth river rocks instead of paper. That’s true, and they also use dried cobs of corn, minus the kernels, as another song notes. In a funny sight gag, the backup musicians in this video play while wearing ridiculous, improvised protective gear. The bass player uses a plastic water bottle like a helmet, and the guitarist dons a beekeeper’s gear to veil his face. It closes with a notice spoofing the norms of filmmaking: “CLARIFICATION: For this video, only half a roll of hygienic paper was used, and most of it was able to be re-utilized.”

Accentuate the Positive

Discordant notes are the exception in this new crop of virus videos. Most of the artists promote a spirit of togetherness in time of crisis. In this last example, “Quédate en Casa” (Stay Home), a Cuban artist based in Spain, one of the hardest hit countries in the pandemic, performs an infectious tune with rap verses and a reggaeton chorus. His name is Ariel de Cuba, and he wrote, recorded, and made a video of the song at his home studio near Madrid, with the help of his son and daughter, “all without leaving the house.” He thanks the health workers for risking their lives, and urges all people to come together as one family.

Discordant notes are the exception in this new crop of virus videos. Most of the artists promote a spirit of togetherness in time of crisis. In this last example, “Quédate en Casa” (Stay Home), a Cuban artist based in Spain, one of the hardest hit countries in the pandemic, performs an infectious tune with rap verses and a reggaeton chorus. His name is Ariel de Cuba, and he wrote, recorded, and made a video of the song at his home studio near Madrid, with the help of his son and daughter, “all without leaving the house.” He thanks the health workers for risking their lives, and urges all people to come together as one family.

The song was quickly picked up by Lessier Herrera, a Zumba instructor based in Bologna, Italy, another country ravaged by COVID-19. The exercise video shows the instructor and two women in gym clothes, appearing to dance together to the song, perhaps violating the distancing rules they’re promoting. But you quickly see it’s a split screen, and each dancer is in a different location, following the same moves.

Separate, but together.

--Agustín Gurza

Blog Category

Tags

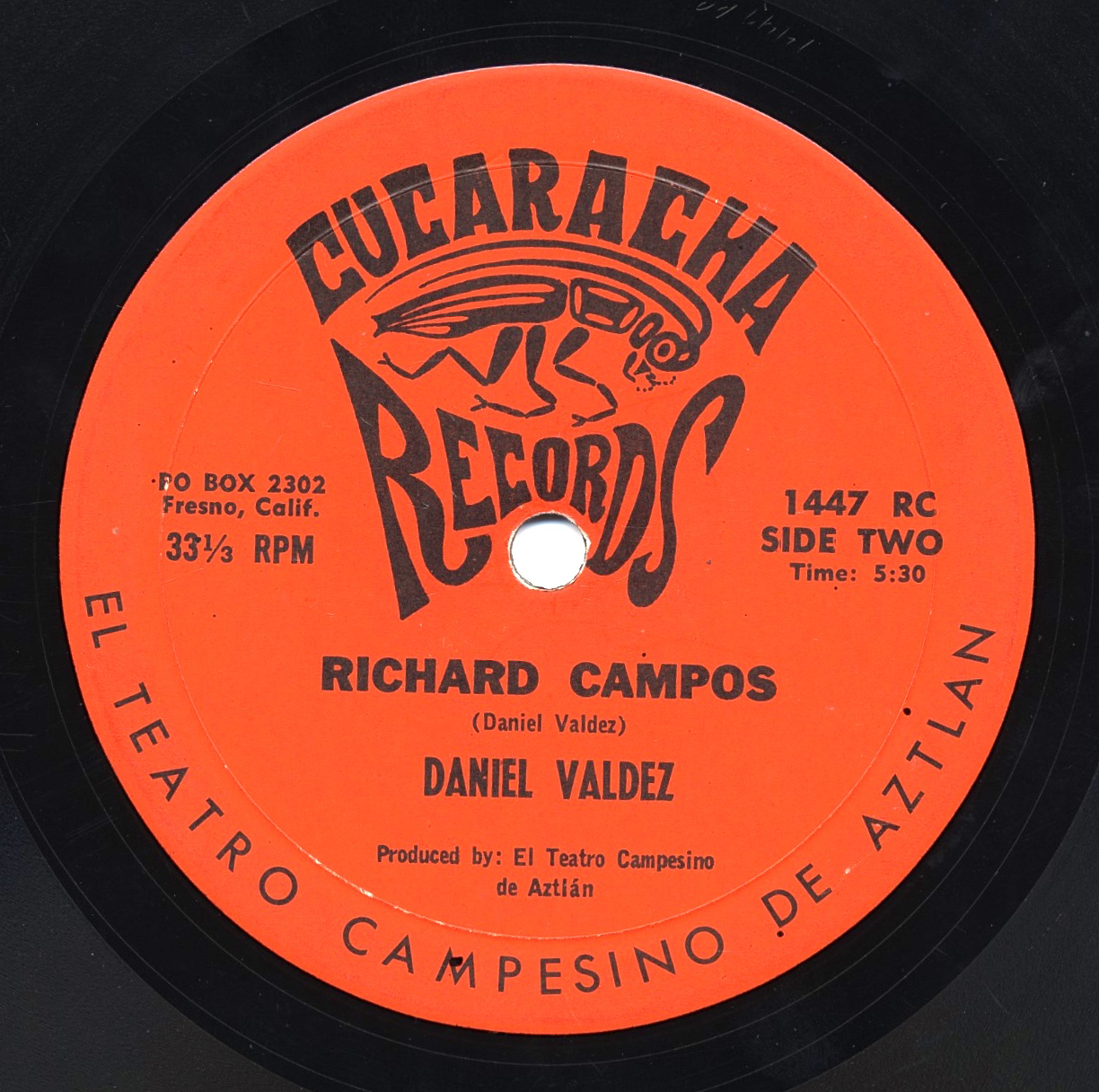

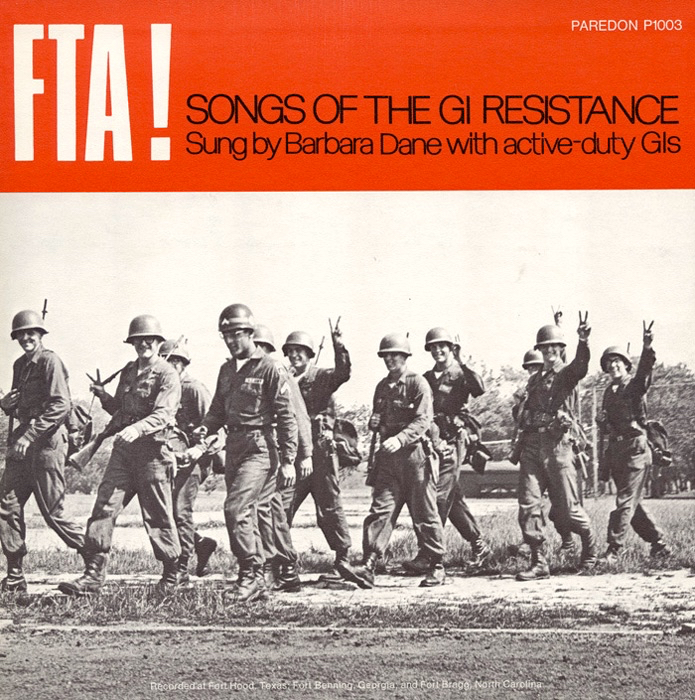

Images

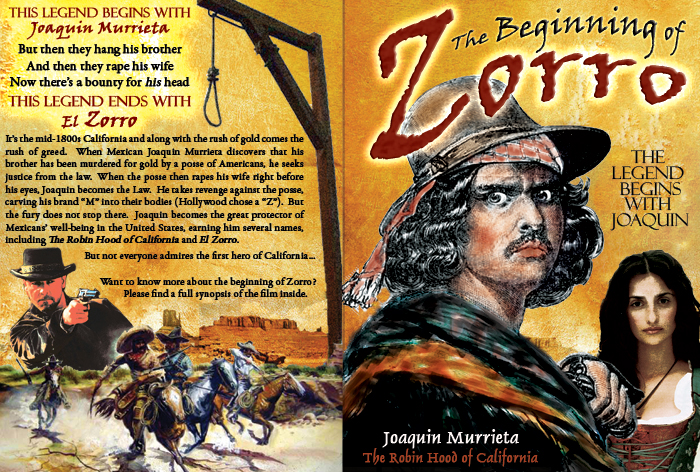

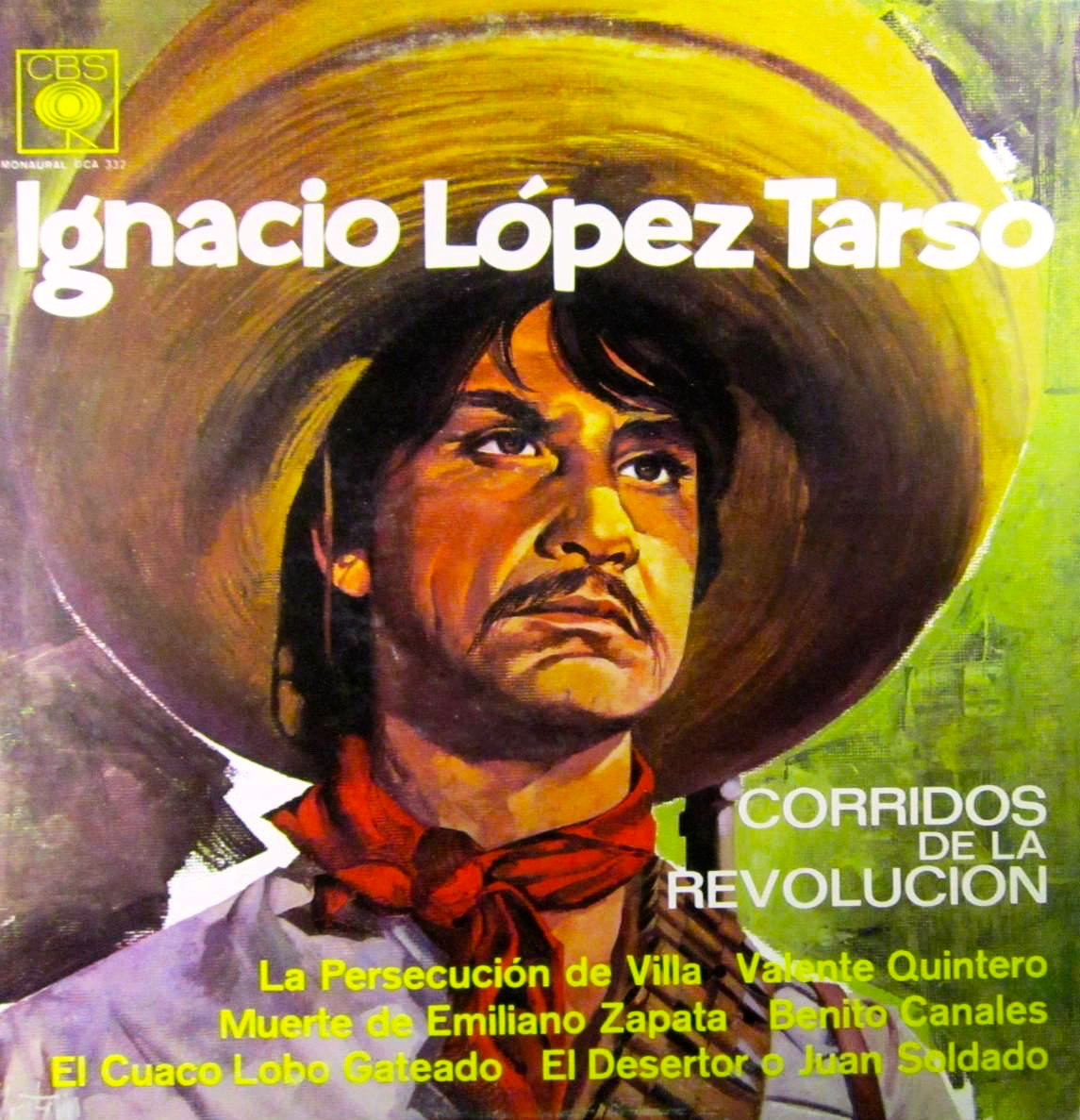

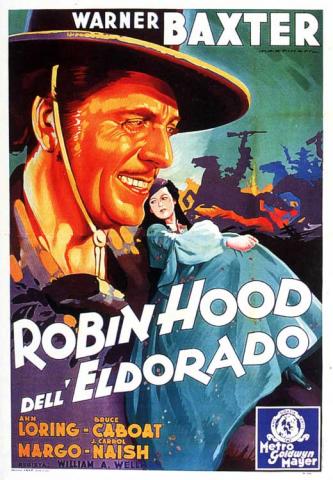

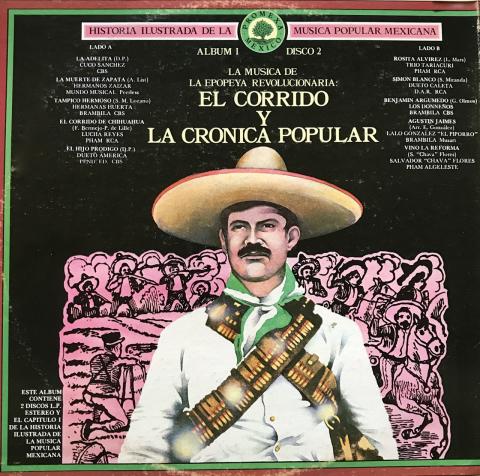

The corrido is a traditional Mexican ballad that tells true stories of heroes and villains in verse. It was once considered a reliable news source, in the era when the poor had limited access to other forms of media. Today, corridos are still written about current events, from the terrorist attacks of 9/11 to the battles over immigration and the election of Donald Trump.

The corrido is a traditional Mexican ballad that tells true stories of heroes and villains in verse. It was once considered a reliable news source, in the era when the poor had limited access to other forms of media. Today, corridos are still written about current events, from the terrorist attacks of 9/11 to the battles over immigration and the election of Donald Trump.

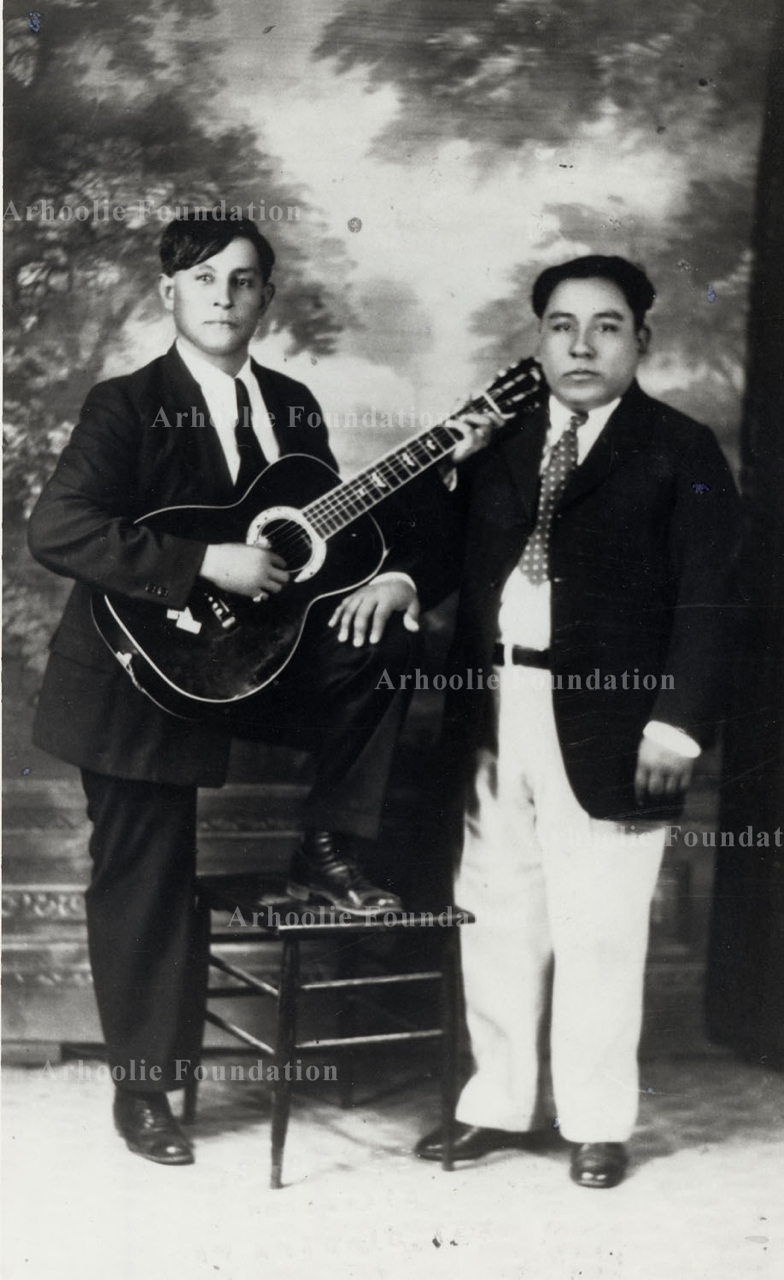

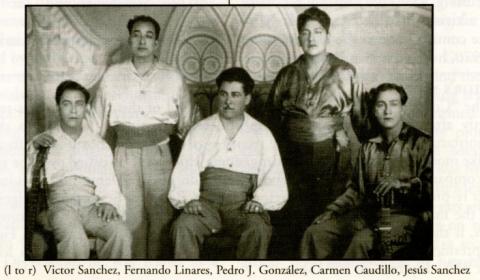

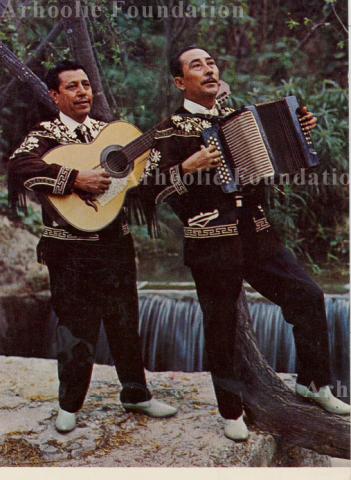

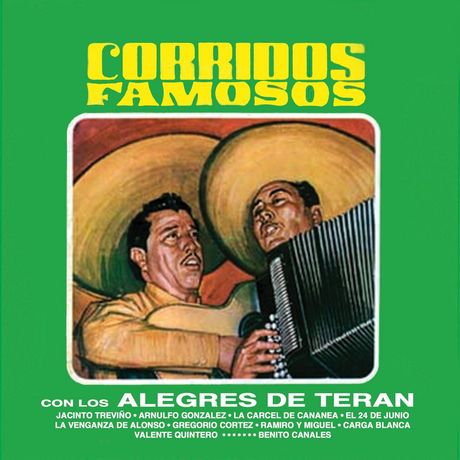

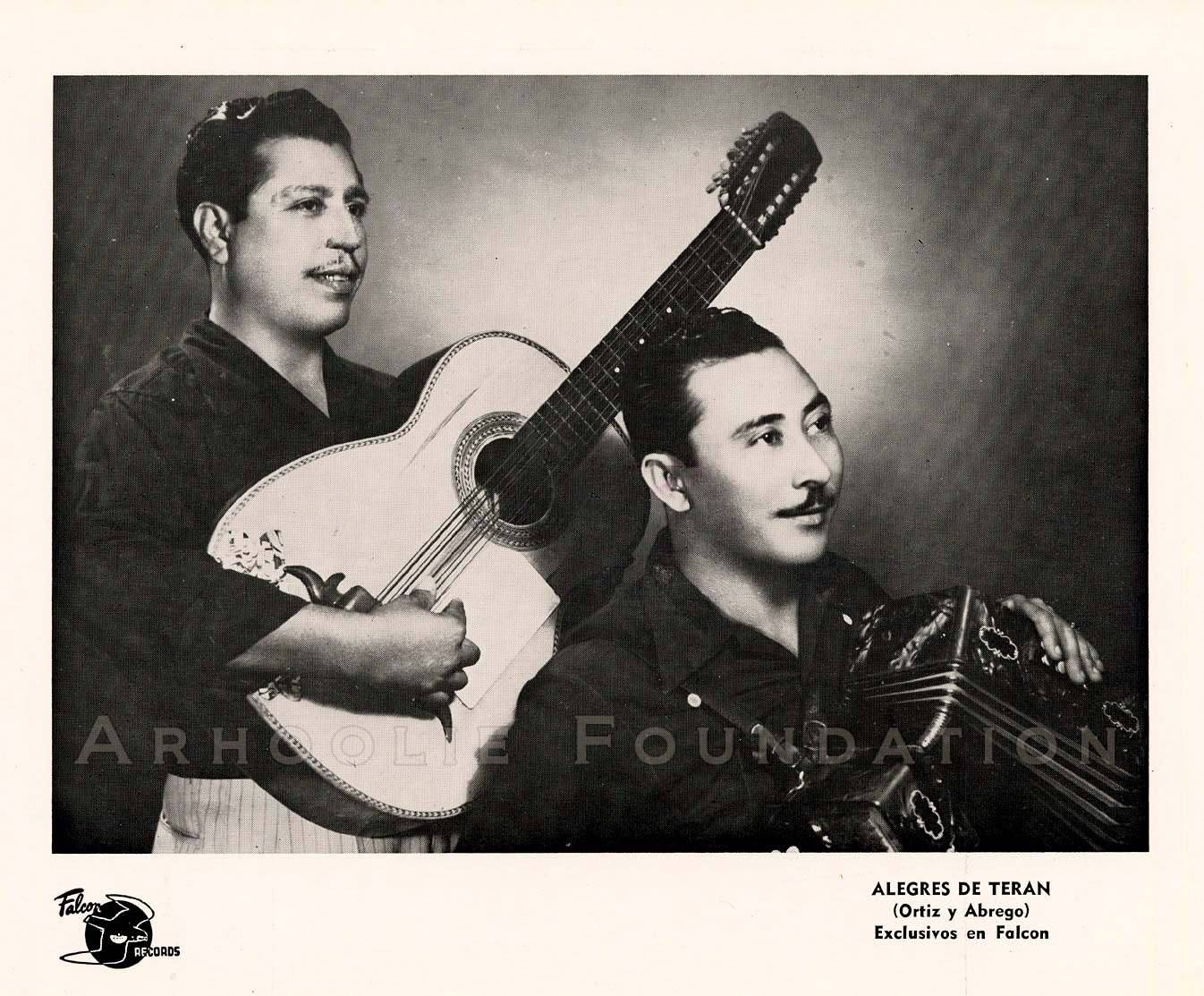

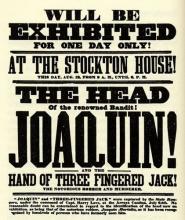

The Frontera Collection has three versions of the corrido recorded in two parts, all by some incarnation of Los Madrugadores. The 1934 recording on the

The Frontera Collection has three versions of the corrido recorded in two parts, all by some incarnation of Los Madrugadores. The 1934 recording on the