the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center,

the Arhoolie Foundation,

and the UCLA Digital Library

The corrido is a traditional Mexican ballad that tells true stories of heroes and villains in verse. It was once considered a reliable news source, in the era when the poor had limited access to other forms of media. Today, corridos are still written about current events, from the terrorist attacks of 9/11 to the battles over immigration and the election of Donald Trump.

The corrido is a traditional Mexican ballad that tells true stories of heroes and villains in verse. It was once considered a reliable news source, in the era when the poor had limited access to other forms of media. Today, corridos are still written about current events, from the terrorist attacks of 9/11 to the battles over immigration and the election of Donald Trump.

Mexican Americans have also used the corrido to tell stories about their experiences as United States soldiers. The wartime corrido is a tradition that can be traced from the Mexican Revolution to the Vietnam War and, more recently, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Some of these songs perform the customary purpose of honoring specific war heroes, often from poor immigrant neighborhoods, whose stories and sacrifices may not otherwise be publicly recognized. The songs also express a range of sentiments about the sons of immigrants giving their lives for their adopted country, ranging from patriotism to protest.

Mexican Americans have also used the corrido to tell stories about their experiences as United States soldiers. The wartime corrido is a tradition that can be traced from the Mexican Revolution to the Vietnam War and, more recently, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Some of these songs perform the customary purpose of honoring specific war heroes, often from poor immigrant neighborhoods, whose stories and sacrifices may not otherwise be publicly recognized. The songs also express a range of sentiments about the sons of immigrants giving their lives for their adopted country, ranging from patriotism to protest.

As I wrote last week, the Frontera Collection contains scores of songs written by and about Mexican-Americans being called to defend the country and perhaps die in far-off lands. They are not all corridos. But they are almost always heartbreaking stories of young men accepting their destiny, hoping to survive but resigned to whatever may come.

The values expressed in many of these songs strike common themes: bravery, duty, honor, loyalty. Some verge on the jingoistic, condemning communists and Asians in the same breath. But most reveal the feelings of the common recruit, el soldado razo. He is the drafted soldier who has no choice but to fight, yet wraps his service in a patriotic rationale.

There is often a duality to the patriotism, a split loyalty between two countries. Oddly, war helps merge those two loyalties in songs that often invoke the soldier’s ethnic heritage. They vow to prove in battle that Mexican Americans are courageous defenders of the United States, regardless of the reasons for war.

Many songs also refer to mothers and to Mother Mary. Soldiers worry about leaving their madrecitas alone, and they pray to the Virgin de Guadalupe to bring them home safely so they can be reunited, or meet their mothers again in heaven if they die.

Many songs also refer to mothers and to Mother Mary. Soldiers worry about leaving their madrecitas alone, and they pray to the Virgin de Guadalupe to bring them home safely so they can be reunited, or meet their mothers again in heaven if they die.

Fathers are also represented in these songs, such as the World War II veteran who must see off his son to Vietnam, or the ghost of a dead soldier who, from his own coffin, sees his son crying for the loss of his father.

We start this week with the “Corrido of Ricardo Campos,” the tragic true story of the orphan kid from California whose body was shipped back from the battlefield with nobody to claim it.

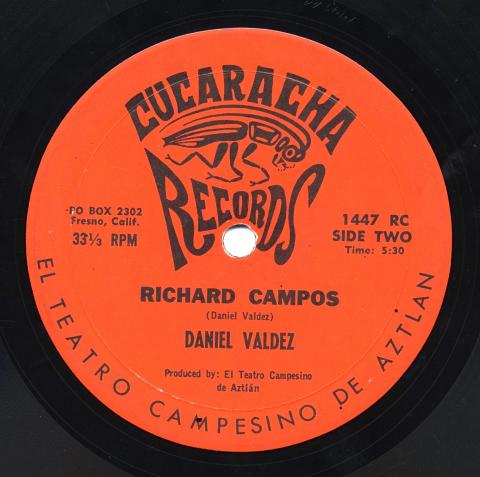

“Richard Campos” by Daniel Valdez (Cucaracha 1447-RC)

Singer-songwriter Daniel Valdez, a veteran of the Teatro Campesino and a star of the play Zoot Suit, penned this powerful anti-war protest based on the Campos case, which got a lot of coverage at the time.

According to the UPI, Sgt. Richard F. Campos was 26 when he was killed in Vietnam by an enemy sniper on December 6, 1966. His body was shipped back to the States, but at first nobody came forward to claim it. His remains were stored at the Oakland Army Terminal for more than two weeks, the article states, “while the Army searched for a living relative.”

Campos had enlisted in 1958 when he was just 17. At the time, he was an orphan and a ward of the state of California. The details of his tragic childhood are wrenching, as described in a short bio from Remembering our Own, by Robert L Nelson.

Richard Frederick Campos was born on September 15, 1940, in Carbondale, California, near Sacramento. His mother was an unwed teenager; he never knew his father. When he was barely two, as his mother lay dying of tuberculosis, he was sent to live with an aunt in San Francisco. Five years later, she also died. The boy was then sent to a foster home, but four years later his foster mother had to give him up due to her failing health. By the age of 12, he had lost three mothers and three homes. He was then taken in by Salesian priests at St. Francis School in Watsonville, where he was remembered as a handsome, friendly boy who played on the championship basketball team and took a top trophy in a citywide marble competition.

Richard Frederick Campos was born on September 15, 1940, in Carbondale, California, near Sacramento. His mother was an unwed teenager; he never knew his father. When he was barely two, as his mother lay dying of tuberculosis, he was sent to live with an aunt in San Francisco. Five years later, she also died. The boy was then sent to a foster home, but four years later his foster mother had to give him up due to her failing health. By the age of 12, he had lost three mothers and three homes. He was then taken in by Salesian priests at St. Francis School in Watsonville, where he was remembered as a handsome, friendly boy who played on the championship basketball team and took a top trophy in a citywide marble competition.

The Nelson biography and other tributes can be found on a website honoring Vietnam veterans. But few knew the full story as his body lay at the terminal in a gray metal coffin, virtually an unknown soldier. Eventually, as a result of widespread publicity, the Army located a long-lost uncle, a 57-year-old farmworker named James Diego Campos, allowing the soldier to be laid to rest at Golden Gate National Cemetery in San Bruno. The funeral was held on News Year’s Eve 1966, almost a month after his death.

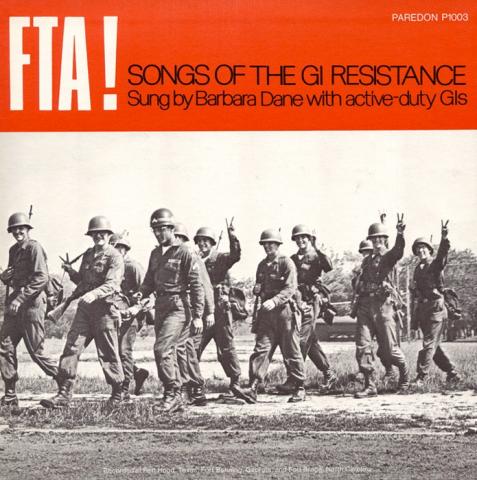

At the end of the bio, Nelson incorrectly notes that the song in the soldier’s honor was written by Barbara Dane, a folksinger and peace activist. Dane did record a version of the Valdez song entitled “The Ballad of Richard Campos,” available on the compilation FTA! Songs of the GI Resistance, released by Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. But she didn’t write it.

At the end of the bio, Nelson incorrectly notes that the song in the soldier’s honor was written by Barbara Dane, a folksinger and peace activist. Dane did record a version of the Valdez song entitled “The Ballad of Richard Campos,” available on the compilation FTA! Songs of the GI Resistance, released by Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. But she didn’t write it.

To Nelson, turning Campos into an anti-war cause célèbre seemed like “an ironic ending for this professional soldier.” The Valdez lyrics go further: they turn his death into a Chicano civil rights cry.

In a terminal in Oakland lies a brown body of a man,

Dead at 27, dead and gone to heaven.

Killed far away in Vietnam.

So they shipped you back to where you came from.

Like a dummy you were tossed around in an airplane.

Back to the hell from which you tried to escape,

Back to the so-called free United States.

Should a man,

Should he have to kill

In order to live like a human being in this country?

The Valdez recording appears on the Cucaracha Records label, based in Fresno and produced by El Teatro Campesino de Aztlán, the farmworker theater troupe founded by his brother, playwright Luis Valdez of Zoot Suit fame. The Frontera Collection features another song about the Campos tragedy, “El Corrido De Ricardo Campos” by New Mexico singer/songwriter Roberto Martinez and Los Reyes De Albuquerque. One is from an album, Hurricane MHS-10002; the other is a 45-rpm single, Hurricane 45-6982. Both are on the label owned by Al Hurricane Sanchez, known as the father of New Mexico music.

Overt anti-war songs by Chicanos are rare, asserts Kirsten Lustgarten in her 2013 master’s thesis in American Studies at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. In fact, they are virtually unknown, compared to the trove of anti-war songs in English by major artists such as Bob Dylan, Country Joe McDonald, and others.

Overt anti-war songs by Chicanos are rare, asserts Kirsten Lustgarten in her 2013 master’s thesis in American Studies at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. In fact, they are virtually unknown, compared to the trove of anti-war songs in English by major artists such as Bob Dylan, Country Joe McDonald, and others.

The song gap is glaring, she argues, because Mexican-Americans were vastly over-represented within the rank-and-file serving in Vietnam, and thus had a lot more to lose. “That absence works to sideline the contributions and struggles of an ethnic group that is considerable in size,” she writes, adding that “filling in the gap in the historiography is a pressing contemporary need.”

In trying to explain the war song gap, Lustgarten argues that the nature of the corrido genre itself precluded protest songs. Why? “Because the celebratory tradition of the corrido is one of violent resistance, of machismo, and of the individual social bandit.” Corridos for peace did not fit the tradition.

That’s a stretch, because Chicanos at this time were not limiting their interest to corridos. They loved Santana, Little Joe, and Ritchie Valens just as much, if not more. Moreover, they identified with a strong wave of socially conscious music, or nueva trova, coming from Mexico. The Frontera Collection contains other styles, perhaps not properly considered protest songs, in which Mexican-American artists make strong statements against war and its human consequences.

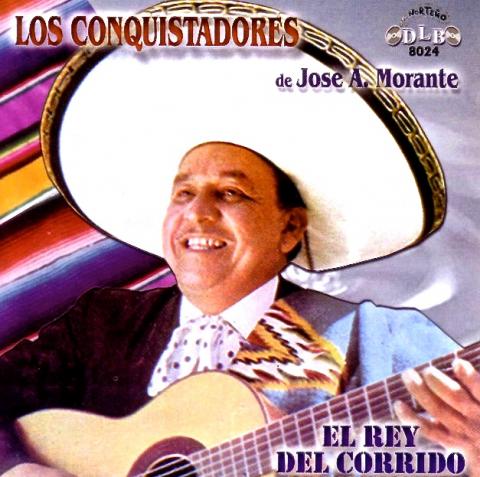

“El Soldado Huerfanito” by Los Conquistadores de José Morante (Norteño 805)

Although the title does not name him, this is another song about Richard Campos. “The Little Orphan Soldier” takes a more personal approach, highlighting the victim’s sad childhood. It includes a minor detail about the teenager volunteering for the Army: “on a cloudy day he went to register.” It begs the question how songwriter José A. Morante would know what the weather was that day, unless he assumed San Francisco was always cloudy.

Although the title does not name him, this is another song about Richard Campos. “The Little Orphan Soldier” takes a more personal approach, highlighting the victim’s sad childhood. It includes a minor detail about the teenager volunteering for the Army: “on a cloudy day he went to register.” It begs the question how songwriter José A. Morante would know what the weather was that day, unless he assumed San Francisco was always cloudy.

Other facts don’t match the official biography. The song states that Campos never knew his mother, and that he was raised in orphanages. That seems calculated to pull listener’s heartstrings.

The story ends with a patriotic verse diametrically opposed to the civil rights outrage expressed by Valdez in his corrido: “He was buried with honors and the land embraced him like one of its own sons.”

Allá en San Francisco descansan sus restos,

Con Gloria y honores su patria le dio.

Lo abrazó la tierra como un hijo suyo.

Ya no es huerfanito, Dios lo recogió.

“Por Que Estamos En Vietnam” by Arnaldo Ramirez (Falcon 1724)

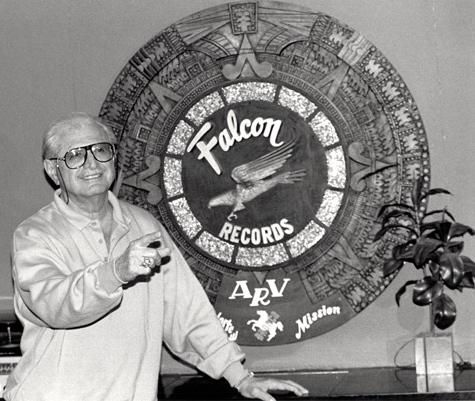

This is a zealous, spoken-word recording, more polemic than poetry. It’s an unabashed defense of the Vietnam War, narrated by Arnaldo Ramirez, who founded Discos Falcon in 1948 in South Texas and pioneered the influential conjunto sound in Tex-Mex music. The title is not a question, “Why are we in Vietnam?” It is an answer, directly quoting one of the architects of the war, U. S. Secretary of State Dean Rusk.

This is a zealous, spoken-word recording, more polemic than poetry. It’s an unabashed defense of the Vietnam War, narrated by Arnaldo Ramirez, who founded Discos Falcon in 1948 in South Texas and pioneered the influential conjunto sound in Tex-Mex music. The title is not a question, “Why are we in Vietnam?” It is an answer, directly quoting one of the architects of the war, U. S. Secretary of State Dean Rusk.

This recording vaguely mimics the old Mexican records that re-create historical events, like audio newsreels. But it is rare to find a recording that is such an overt example of war propaganda. Nevertheless, the song represents a rather mainstream conservative strain in Mexican-American politics, which fuels patriotic fervor. In case there is any doubt as to where Ramirez stands, the record opens with John Philip Sousa's patriotic march “The Stars and Stripes Forever,” which continues as background music during his reading of the Rusk war apologia.

“Cancion Para Un Niño De Vietnam” by Judith Reyes (Catalog Number EH01-B-1)

On the opposite side of the political spectrum, Mexican singer-songwriter Judith Reyes offers a scathing indictment of the U.S. involvement in Vietnam. Her “Song for a Child from Vietnam” jarringly juxtaposes harsh images of war with a sing-song, lullaby melody, identified as “cancion de cuna” on the label. Reyes, a popular protest singer in the 1960s, wrote the song and accompanies herself on guitar. This is also a polemic, but dressed as verse. She calls the gringo “an embarrassment” (una vergüenza) for humanity, and his presence in Vietnam “a calamity.”

Si el gringo esta aquí, que calamidad.

El gringo es vergüenza de la humanidad

Si el gringo se va, feliz me verás,

Porque ahora mi amor, viviremos en paz.

The track is one of three numbers issued on an unusual 33-rpm EP, on a label with no name. The disc has two songs on one side and one on the other. Sharing Side B with the anti-war lullaby is “Gorrilita, Gorrilón,” a critique of Mexican government repression. Side A features “Los Restos de Don Porfirio,” a five-minute string of stinging, satiric verses. It opens with a sarcastic celebration of the return to Mexico of the remains of the dictator overthrown by the Mexican Revolution of 1910. The satire lies in the fact that Porfirio Diaz remains buried in Paris, where he died in exile. He is interred at the Cimetière du Montparnasse, which he shares with France’s leftist intellectual luminaries, Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, another jarring juxtaposition.

The track is one of three numbers issued on an unusual 33-rpm EP, on a label with no name. The disc has two songs on one side and one on the other. Sharing Side B with the anti-war lullaby is “Gorrilita, Gorrilón,” a critique of Mexican government repression. Side A features “Los Restos de Don Porfirio,” a five-minute string of stinging, satiric verses. It opens with a sarcastic celebration of the return to Mexico of the remains of the dictator overthrown by the Mexican Revolution of 1910. The satire lies in the fact that Porfirio Diaz remains buried in Paris, where he died in exile. He is interred at the Cimetière du Montparnasse, which he shares with France’s leftist intellectual luminaries, Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, another jarring juxtaposition.

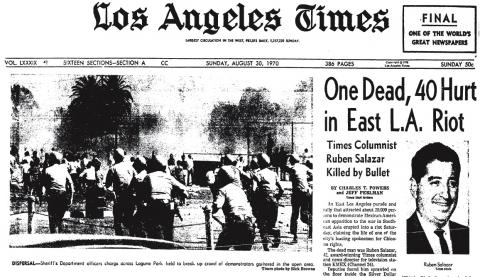

“La Tragedia Del 29 De Agosto” by Lalo Guerrero (Colonial 596)

This corrido memorializes one of the most traumatic days in Chicano history, the death of reporter Ruben Salazar during the Chicano Moratorium, a huge anti-war march in East Los Angeles in 1970. It was written and performed by Lalo Guerrero, considered the father of Chicano music. Interestingly, he opens by making the event personal, placing it near his home and rhyming every line with the Spanish word for home:

En Los Angeles, California, en el barrio junto a mi casa,

El 29 de agosto, gritando “Arriba la raza,”

Se reunió nuestra gente para protestar en masa

Contra la guerra en Vietnam, que sigue y sigue y no pasa.

In the next stanza, Guerrero adds a statistic as rationale for the protest. He notes that 23 percent of war casualties are “young Mexican men” (jóvenes mexicanos), a number he calls “a severe proportion” (una proporción severa), though he probably means disproportion. Then in an occasionally fierce and growling voice, he expresses the protestors’ deep rage:

Cuando vino la policía, la violencia se desató.

El coraje de mi raza luego se desenlazó.

Por los años de injustica, el odio se derramó,

Y como huracán furioso, su barrio lo destrozó

The song takes an unexpected turn at the end. Employing a device often found in Mexican folk songs, Guerrero stops the music to recite a spoken verse, invoking a metaphorical bird as a messenger. But his message at the end is not against the war, but against the protestors for destroying their own neighborhoods. He asks a white dove to tell them to stop, so Salazar will not have died in vain.

Paloma blanca, tu que por doquiera que vas eres símbolo de la paz,

Lleva en tu pico este ramo de azar, y dile a la raza que ya no destroce,

Que no haya muerto en vano Rubén Salazar.

“Corrido a Ray Guzman” by Conjunto Laureles (Nu-Mex NM-101)

P roviding the date of an event is one of the essential elements of the corrido narrative. In the case of Ray Guzman, the first line of his corrido sets the date of his death as January 25, “that was a fatal Tuesday ” (que fue un martes fatal). Other than that, the song provides no details about the circumstances of his death. Instead, the body of the lyric becomes a paean to the fallen soldier, whose “ambition for glory knew no bounds,” who “had no fear in dying,” who “was always first in combat,” who was “Mexican by fortune,” and who was “noble, brave and loyal.”

roviding the date of an event is one of the essential elements of the corrido narrative. In the case of Ray Guzman, the first line of his corrido sets the date of his death as January 25, “that was a fatal Tuesday ” (que fue un martes fatal). Other than that, the song provides no details about the circumstances of his death. Instead, the body of the lyric becomes a paean to the fallen soldier, whose “ambition for glory knew no bounds,” who “had no fear in dying,” who “was always first in combat,” who was “Mexican by fortune,” and who was “noble, brave and loyal.”

In the end, a corrido also normally provides a final farewell. In this case, it’s delivered by the voice of the soldier himself, identifying his hometown in the process: “Adios Lovington querido, ya de su suelo me voy.” The song, written by Manuel Morales, was released on the Nu-Mex label, based in Lovington, New Mexico.

The basic facts found in the song can be verified in a government archive that lists Vietnam casualties by home state. There, we find a listing for Reynaldo Guzman, Marine Corps Lance Corporal, born May 30, 1943, in Lovington, the county seat of Lea County, New Mexico. Died January 25, 1966. Remains recovered: Yes.

“Corrido de Jimmy Aguirre” by Agapito Zuñiga (Discos Escorpión ES-114)

This is a corrido in which the heroic acts of the main character are actually understated. The song, released on the Corpus Christi-based Escorpión label, begins with the usual platitudes about patriotism, bravery, and ethnic pride. (“Jimmy se arrojó al combate, y su nombre hizo valer. Como era Mexicano, hasta morir o vencer.”) The specific acts of bravery that earned our hero the Army’s Distinguished Service Cross are mentioned in just one stanza: Aguirre suffered 50 wounds but still saved other injured soldiers.

The song does not do him justice. The official account of Aguirre’s “exceptionally valorous actions on 4 December 1967 as platoon medic,” reads like the proverbial movie script that would be rejected as too fantastic to be believed.

In the end, composers Jesse Saldivar and Agapito Zuñiga turn the soldier’s profile in courage into a crass Army recruitment ad.

Ya con esta me despido, con sentimiento y afán,

No tengan medio, muchachos, cuando vayan a Vietnam.

“No Naci Pa’ Soldado” by Lalo Guerrero (Colonial 533)

With his renowned sense of humor, albeit sometimes corny, Guerrero in this song explores an ambiguous area between bravery, cowardice and common sense, adding a touch of racism and right-wing anti-communism.

With his renowned sense of humor, albeit sometimes corny, Guerrero in this song explores an ambiguous area between bravery, cowardice and common sense, adding a touch of racism and right-wing anti-communism.

On “I Wasn’t Born to Be a Soldier,” Guerrero is backed by the Mariachi Colonial, a studio band for the label based in Monterey Park, California, east of Los Angeles. The uncertain soldier ponders his future after getting drafted by Tío Sam. If he had married and started a family, like his mother admonished him, he might have dodged the draft and avoided “becoming a target for some “slanty-eyes” (unos ojos estirados). He’d rather be ordered around by his wife than by a sergeant, he says. And he’d rather duck a frying pan than a machine gun.

Mejor me hubiera casado, no sucediera esto ahora

De que me mande un sargento, que me mande mi señora

Mejor capear sartenazos y no una ametralladora.

“It’s not that I’m afraid of them,” Guerrero adds, because he already took his chances “over there in Korea.” But he is wary of the communists who are “hijos de la china roja” (the sons of Red China), playing on a common Spanish profanity. He also calls them “the monkeys of the Vietcong.”

The final verse takes a different tone, abandoning the song’s sarcasm and hostility. In the end, Guerrero brilliantly captures the existential dilemma of the common soldier who can’t quite find his motivation to kill the so-called enemy: “How do they want me to fight if I’m not angry at anybody?”

Adiós les digo a mis cuates, me voy todo aguitado.

No es miedo, es precaución. Yo no nací pa’ soldado.

¿Como quieren que pelen? Con nadie estoy enojado

--Agustín Gurza

0 Comments

Stay informed on our latest news!

Add your comment