Featured Song: “The Ballad of Joaquín Murrieta”

The corrido is perhaps the quintessential genre in Mexican roots music. But as a narrative ballad, it has a close cousin in traditional country and western music. Remember the tale of heartbreak and murder called “El Paso” by country singer Marty Robbins? That song, which reached No. 1 on the Billboard pop and country charts in 1960, has many classic elements of a corrido, including an opening that sets the scene and a protagonist who tragically follows destiny to his death.

Robbins wrote “El Paso” in English while he was driving across Texas with his family. (There’s a rare, speeded-up version performed live on Australian TV in 1964 here.) But corridos can also be transposed across cultures. Take the classic ballad about the controversial California character Joaquín Murrieta. The Frontera Collection has some 20 versions of the song in Spanish, detailing the exploits of the beheaded protagonist, who was alternately considered hero or villain, rebel or bandido. The earliest versions, released as 78-rpm singles, include two-part recordings by Los Madrugadores, the famous Los Angeles-based radio act (more about these tracks in a moment).

I was recently surprised to find a modern English-language version of the Murrieta saga by a harmonizing family trio named Sons of the San Joaquín, based in the Fresno area. Their song “The Ballad of Joaquín Murrieta” was written by singer Jack Hannah, who formed the vocal group with his brother Joe Hannah and Joe’s son Lon, a music teacher in the Visalia school district. The song, released on the group’s 2005 album Way Out Yonder, is a traditional cowboy ballad, adorned with Spanish guitars and subtle mariachi-style horns.

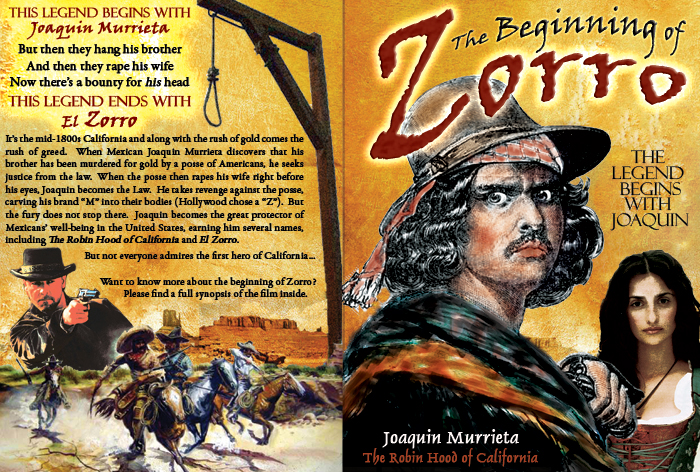

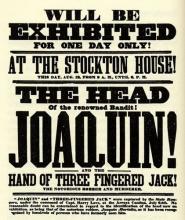

Hannah’s lyrics reflect both fact and legend in the Murrieta story. He alludes to the rebel’s Sonora origins, his tall and handsome appearance, his drive to join the Gold Rush and the vicious beating he suffered at the hands of assailants who also raped his wife. Murietta vowed to take revenge, the song continues, and “the rage of Murrieta swept throughout the San Joaquin.” In a spoken part of the story, Hannah refers to California governor John Bigler, who in 1853 placed a bounty on Murrieta’s head and named a veteran of the U.S.-Mexico War, Captain Harry Love, to lead the manhunt with newly deputized California State Rangers.

Of course, the story ends badly for Murrieta, who was killed on July 25, 1853, along with his notorious sidekick known as Three-Fingered Jack. A state historical landmark now marks the spot where they made their last stand, described as Murrieta’s headquarters at Arroyo de Cantua near Coalinga, off Interstate 5 southwest of Fresno. Hannah’s version skips over the fact that Murrieta’s head was cut off and ghoulishly put on display in mining towns throughout the state.

Later, the dead man’s legend grew when people started claiming it wasn’t really Murrieta who was killed. Hannah handles these historic ambiguities with a poetic device, adding phrases such as “the story goes” or “so they say.”

His final verse, however, plays up the Murrieta myth.

The saga ends, but did it?

Joaquín lives, the people say.

For many swear they saw him mount and swiftly ride away.

And down in old Sonora

Where the days are hot and long,

If you listen you can hear young señoritas sing his song

And the tale unfolds.

That last part is true. People still sing the ballad of Joaquín Murrieta, who became a symbol of resistance in the Chicano Movement of the 1960s. When I was in college at UC Berkeley, I was part of a Chicano student group, Frente, which ran a dormitory and cultural center near campus called Casa Joaquín Murrieta.

Record producer Chris Strachwitz and the Frontera Collection were influential in keeping the Murrieta

myth alive during that era, according to Manuel Peña, an ethnomusicologist and author of books on Tex-Mex music. Peña notes that Murrieta “actually came to the attention of modern scholarship in the 1970s” after Strachwitz included a version of the song in a corrido compilation released on Arhoolie, his independent label.1 The corrido in question is that two-part 78 rpm by Los Madrugadores (The Early Risers), named for its pre-dawn radio show that served as an alarm clock for Mexican field workers during the Great Depression. The show also featured commentary by Pedro J. González, the group leader who spoke out against the mass deportations of Mexicans at that time.

In a case of life imitating art, the message of the Murrieta corrido was reinforced when González was himself sent to San Quentin prison on trumped-up rape charges in 1934, the very year Los Madrugadores recorded the song. As Ethnic Studies professor Shelley Streeby noted, “[T]he story of the unjust treatment and criminalization of a Mexican immigrant (Murrieta) in the United States must have taken on new and tragic resonances for that working-class audience during these years of intensified nativism and forced repatriation, especially in light of González’ harsh experiences with the law.”2

The Frontera Collection has three versions of the corrido recorded in two parts, all by some incarnation of Los Madrugadores. The 1934 recording on the Vocalion label was also released on Columbia with somewhat better fidelity. A slightly different version (same lyrics, different arrangement) was released on Decca by Los Hermanos Sanchez y Linares, composed of the two original members of Los Madrugadores, the brothers Jesus and Victor Sanchez, along with Fernando Linares. (The group has its own compilation CD on Arhoolie featuring the two-part Murrieta corrido: Pedro J. González and Los Madrugadores, 1931-1937 [Arhoolie 7035].)

The Frontera Collection has three versions of the corrido recorded in two parts, all by some incarnation of Los Madrugadores. The 1934 recording on the Vocalion label was also released on Columbia with somewhat better fidelity. A slightly different version (same lyrics, different arrangement) was released on Decca by Los Hermanos Sanchez y Linares, composed of the two original members of Los Madrugadores, the brothers Jesus and Victor Sanchez, along with Fernando Linares. (The group has its own compilation CD on Arhoolie featuring the two-part Murrieta corrido: Pedro J. González and Los Madrugadores, 1931-1937 [Arhoolie 7035].) Some scholars say this ballad does not meet all the official characteristics of a true corrido, starting with the fact that there is no narrator. Instead, the story is told in the first-person by Murrieta himself. But one verse, quoted in English and Spanish on a Murrieta website, shows how the theme might still resonate with Mexican-Americans today in light of the current struggle for immigration reform.

I'm neither Chilean nor a foreigner

to this land I tread.

California belongs to Mexico

because God wished it so.

And in my stitched sarape

I carry my baptismal certificate.

No soy chileno ni extraño

en este suelo que piso.

De México es California,

porque Dios así lo quiso

Y en mi sarape cosida

traigo mi fe de bautismo.

-Agustín Gurza

1“Música fronteriza / Border Music” by Manuel Peña. Reprinted with permission of The Regents of the University of California from Aztlán: A Journal of Chicano Studies, vol. 21, nos. 1-2, pp. 191-225, UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center.

2Streeby, Shelley. American Sensations: Class, Empire, and the Production of Popular Culture. Berkeley: University of California, 2002. Print.

Blog Category

Tags

Images