The Mexican Corrido: Ballads of Adversity and Rebellion, Part 4: Corridos of the Mexican Revolution

Part 4: Corridos of the Mexican Revolution

The Mexican Revolution of 1910, with its epic heroes facing life-and death struggles, ushered in a golden age of the corrido. In the introduction to his 1954 anthology, “El Corrido Mexicano,” corrido historian Vicente T. Mendoza asserts that the narrative ballad achieved its “definitive character” during Mexico’s decade of Civil War, acquiring “its true independence, fullness and epic character in the heat of combat.”

American adventurer and historian Edward Larocque Tinker had a front-row seat to the creation of a corrido on that revolutionary battlefield. In 1915, Tinker was a civilian observer with Pancho Villa’s troops during the fabled Battle of Celaya, a major defeat for Villa that signaled a turning point in the revolution. On the evening after the battle, Tinker describes hearing voices and guitars as he wandered along the boxcars where Villa’s tired, bedraggled troops were quartered. Looking for the source of the music, he came upon a group of men and women around a campfire, “listening in the moonlight like fascinated children to the singing of three men.” He gives the following account:

American adventurer and historian Edward Larocque Tinker had a front-row seat to the creation of a corrido on that revolutionary battlefield. In 1915, Tinker was a civilian observer with Pancho Villa’s troops during the fabled Battle of Celaya, a major defeat for Villa that signaled a turning point in the revolution. On the evening after the battle, Tinker describes hearing voices and guitars as he wandered along the boxcars where Villa’s tired, bedraggled troops were quartered. Looking for the source of the music, he came upon a group of men and women around a campfire, “listening in the moonlight like fascinated children to the singing of three men.” He gives the following account:

“I too was fascinated and thought they sang some old folk tale. As verse after verse, however, took the same melodic pattern I suddenly realized that this was no ancient epic, but a freshly minted account of the battle of the day before.... It was a corrido – hot from the oven of their vivid memory of the struggle between Villa and Obregon – the first one I had ever heard.”

The battle of Celaya is well documented in corridos, with at least a dozen renditions in the Frontera Collection, including three, two-part recordings on 78s. Several of these ballads about the battle are also included in a compilation issued by Arhoolie Records in 1996 as a box set: The Mexican Revolution: Corridos about the Heroes and Events 1910-1920 and Beyond! The collection features corridos about other important battles, typically titled after the city that is taken in battle, such as “La Toma de Torreón” (my hometown and one of Villa’s center of operations), as well as the taking of Zacatecas, Guadalajara, and Matamoros. There are also many corridos written about revolutionary figures, major and minor, on both sides of the civil war, including Emiliano Zapata, the iconic agrarian reformer, and Porfirio Diaz, the overthrown dictator.

As we have seen in previous parts of my series on the genre (linked below), corridos as an oral tradition pre-date the invention of recorded sound. And the earliest recorded corridos also pre-date the 1910 uprising. Those seminal recordings, made in Mexico City, include two famous corridos, “Heraclio Bernal” and “Ignacio Parra,” about rebels active in the late 1880s during the Diaz dictatorship. Both were recorded by singer Rafael Herrera Robinson in 1904, on cylinders for the Edison recording company.

As we have seen in previous parts of my series on the genre (linked below), corridos as an oral tradition pre-date the invention of recorded sound. And the earliest recorded corridos also pre-date the 1910 uprising. Those seminal recordings, made in Mexico City, include two famous corridos, “Heraclio Bernal” and “Ignacio Parra,” about rebels active in the late 1880s during the Diaz dictatorship. Both were recorded by singer Rafael Herrera Robinson in 1904, on cylinders for the Edison recording company.

A few years later, Herrera re-recorded many of his early cylinder tracks for the Victor and Columbia labels, which had also set up subsidiaries in the Mexican capital. However, the singer did not reprise his original recordings about the two rebels, who the government discredited as common criminals (“bandidos vulagres”). Why the omission? The late James Nicolopulos, one of the leading corrido experts in the U.S., argued that political pressure had forced the artist to abandon these rebel ballads due to their “seditious undercurrent.” In other words, corridos were censored as a voice of dissent.

In those days, Nicolopulos explains, the nascent recording industry based in Mexico City was “geared to the tastes of the ruling classes.” The industry and the social elites shunned the corrido as subversive, not to mention aesthetically unworthy. This entrenched social prejudice, combined with the high cost of discs and record-playing equipment, largely excluded the genre from recording studio rosters because it was considered inferior music for the country’s marginalized classes.

Two factors, one historical and one technological, converged to stimulate the commercial recording of corridos, and in the process, turn the American Southwest into a mecca for the folk art form.

First, the Mexican Revolution had led to a mass migration of the country’s poor north into the United Sates, as people fled the chronic violence and sought some social stability. During the same period, meanwhile, a technological revolution transformed the old mechanical methods of sound recording. With the advent of the electrical recording process in the 1920s, recording equipment became less expensive and much more mobile. As a result, record labels could more readily take their recording equipment to where their artists and audiences were located.

First, the Mexican Revolution had led to a mass migration of the country’s poor north into the United Sates, as people fled the chronic violence and sought some social stability. During the same period, meanwhile, a technological revolution transformed the old mechanical methods of sound recording. With the advent of the electrical recording process in the 1920s, recording equipment became less expensive and much more mobile. As a result, record labels could more readily take their recording equipment to where their artists and audiences were located.

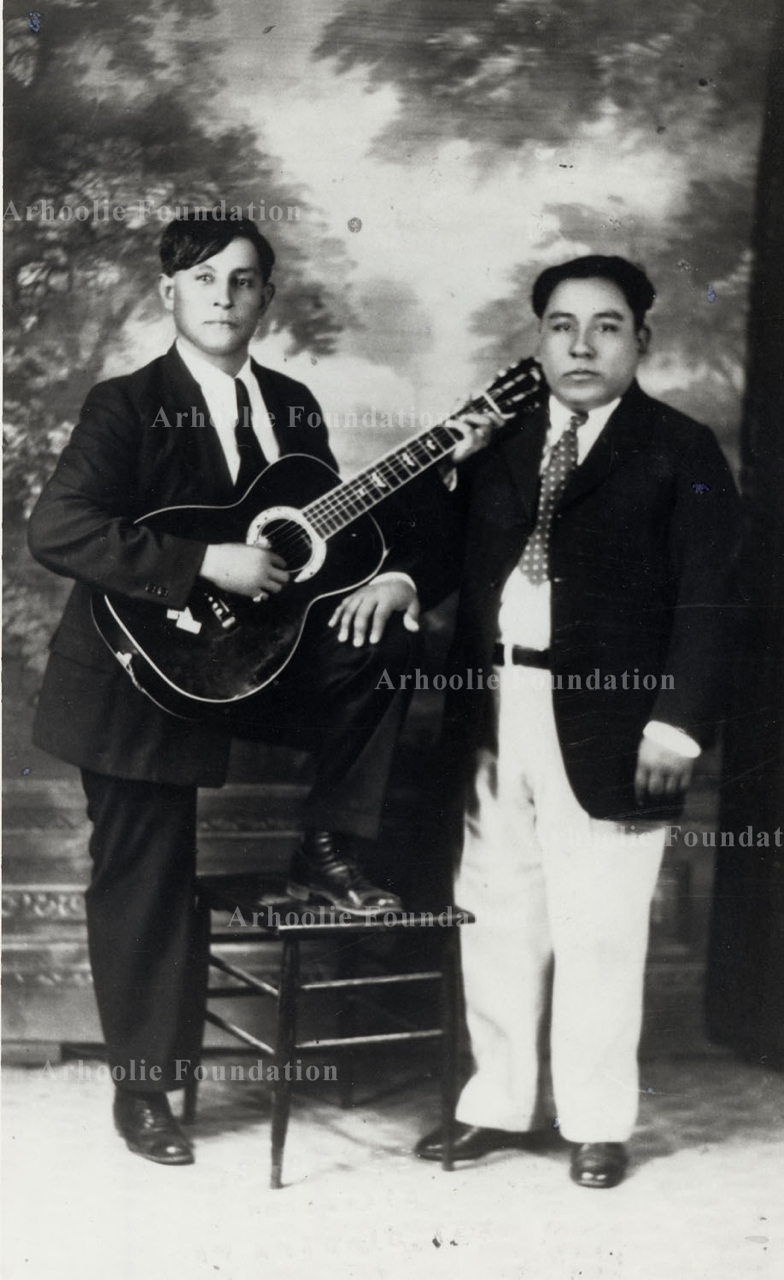

These social and technological developments led to a boom era for corrido recordings, between 1928 and the 1940s. Cities all along the Sunbelt -- El Paso, San Antonio, Los Angeles -- became the new capitals of the corrido recording industry. One side effect of this cross-border shift was the creation of a market for the corrido that was immune to the upper-class sensibilities and censorship of Mexico City’s centralized music business.

These changes gave corrido composers and performers on the U.S. side of the border a creative advantage they did not have in their native country – freedom of expression. “The shift of technology across the border had created the discursive space necessary for the expression of sentiments that could not have been undertaken in Mexico,” writes Nicolopulos, who was a professor of Latin American studies at the University of Texas at Austin.

Songs about the exploits of Pancho Villa, the revolutionary leader operating in northern Mexico, constitute an entire sub-set of the genre known as “corridos villistas.” According to Nicolopulos, the earliest of these was made in New York in 1918; as such, it was also one of the first revolutionary corridos recorded in the United States. The seminal Villa ballad came two years after the revolutionary leader mounted his daring raid on Columbus, New Mexico, prompting the U.S. to send 10,000 troops across the border to capture him. The song lionized Villa’s Zorro-like ability to elude the American force, led by Gen. John J. "Black Jack" Pershing, who was mocked for his failure despite his superior military strength.

Villa ballads cover a wide range of subjects. They herald his favorite horse (“El Siete Leguas”), his elite cavalry (“Los Dorados de Villa”), his strategic use of trains to move troops ("Ahí viene el tren"), his wily guerilla tactics (“La Persecución de Villa”), and of course, his ambush and assassination in 1923 (“La Muerte de Pancho Villa” and “La Tumba de Villa”).

The Frontera Collection also has a two-part corrido entitled “Pancho Villa and Carranza,” by the duo Genaro Rodriguez y Juan Chavez, a clear precursor of subsequent songs about the Pershing expedition. Like other two-part ballads of the era, this 78-rpm recording on the Okeh label includes a few additional verses that don’t appear in later versions.

The Frontera Collection also has a two-part corrido entitled “Pancho Villa and Carranza,” by the duo Genaro Rodriguez y Juan Chavez, a clear precursor of subsequent songs about the Pershing expedition. Like other two-part ballads of the era, this 78-rpm recording on the Okeh label includes a few additional verses that don’t appear in later versions.

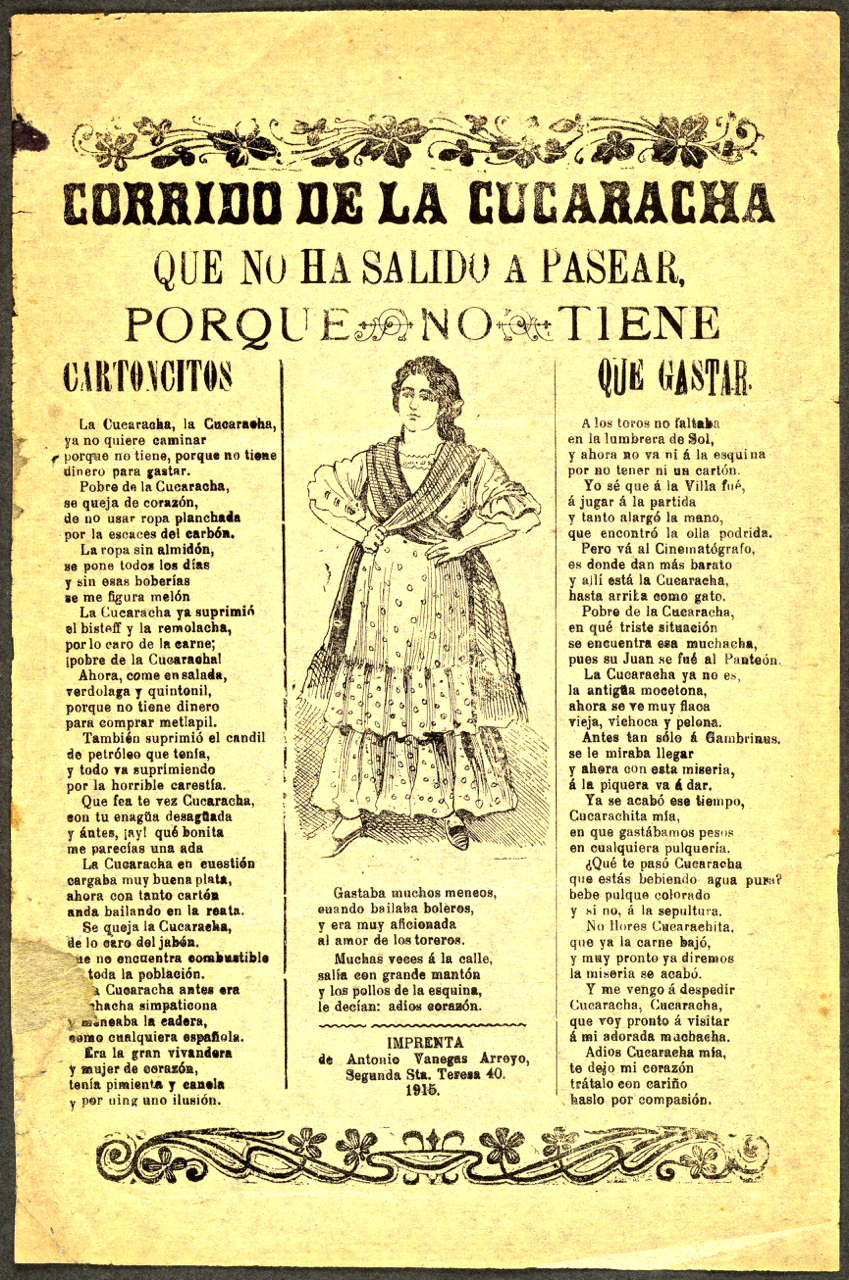

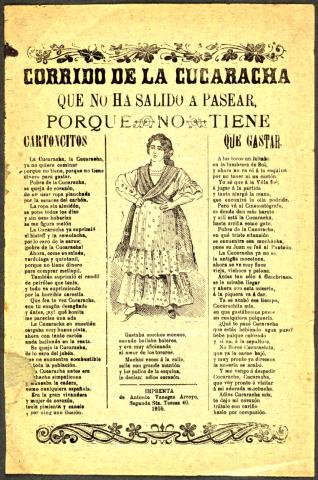

By far, the most popular song about Villa is the iconic “La Cucaracha,” which became a revolutionary anthem, “the Mexican equivalent of America’s Yankee Doodle,” as one blogger puts it. The catchy tune is filled with metaphors alluding to rivalries between revolutionary and counter-revolutionary camps. Though it has roots in medieval Spain, its adaptation during the revolution added most of the stanzas familiar today. In the pro-Villa versions, according to one common interpretation, the cockroach represents President Victoriano Huerta, a traitor who helped plot the assassination of Francisco Madero, the country’s first revolutionary president. An alternative, though rare, interpretation holds that the cockroach (which “can no longer walk”) represents Villa’s car, which his men had to push when it ran out of gas. In still other versions, lyrics were re-written to favor Huerta, or some other faction.

One of the earliest recordings of the song in the Frontera Collection is performed by the Mexican Bluebird Orchestra, a scratchy 78 on the Bluebird label. The lyrics, sung by a chorus, include the famous opening stanza about the cucaracha being unable to walk because it ran out of marijuana (“porque no tiene, porque le falta, marihuana que fumar”). With a refined orchestral arrangement, the song mocks the forces of Venustiano Carranza, a revolutionary leader who broke with Villa and was a common target of the song’s satirical rhymes.

Today, there are scores of recordings of the perennial ditty, with both political and non-political messages, and some instrumentals with no lyrics at all.

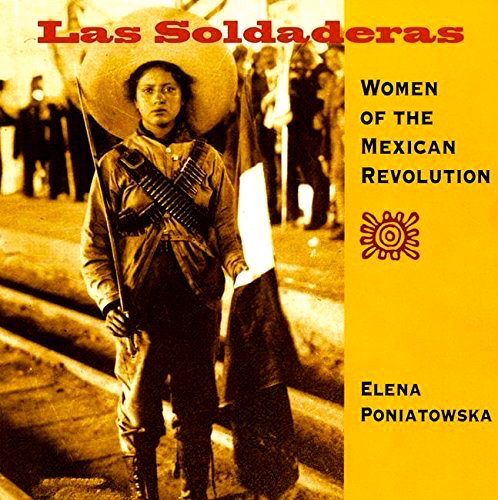

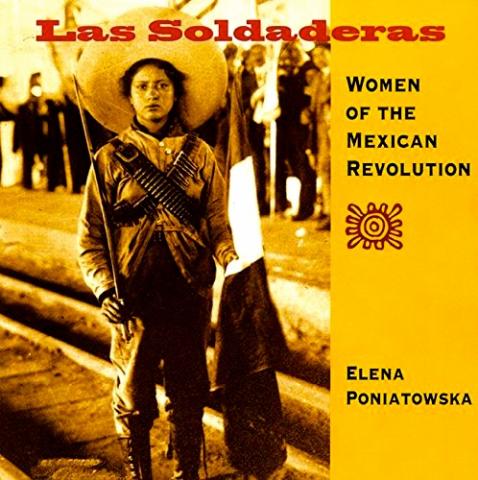

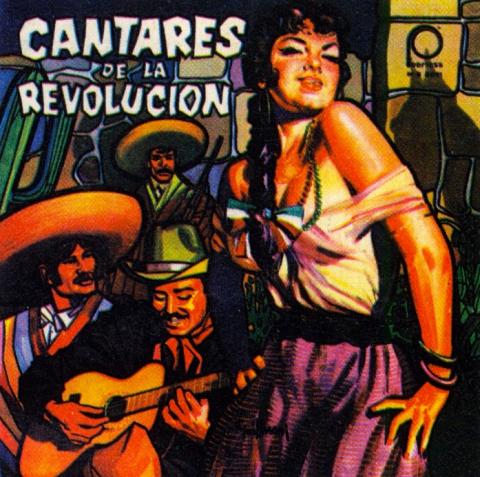

Another revolutionary classic, equally familiar to most Mexicans, is “La Adelita,” a corrido about the women warriors who went to battle alongside the men, also known as soldaderas. There are various versions of the Adelita theme, but the most famous has a peppy, polka-type melody suitable for instrumentals and fun for dancing. The famous lyrics to the song – as performed in this nicely arranged version by Los Hermanos Zaizar with Mariachi Mexico de Pepe Villa – reduces the female fighter to an object of desire for the male troops. The catchy chorus would today be considered a stalker’s anthem, as her besotted sergeant vows to follow her “por tierra y por mar” (by land and sea) if she were to leave with another man. The song appears in a collection of revolutionary tunes, “Cantares de la Revolución” on Mexico’s Peerless label, with a cover that highlights the woman’s sexuality, not her bravery in battle.

One notable exception is a more recent corrido titled “El Rebozo Balaceado” (The Bullet-Riddled Rebozo), about a soldadera who gives her life in Villa’s battle for Torreón, felled on the battlefield with her rifle and her bloody Mexican shawl. It’s sung as a male-female duet by composer Victor Cordero “y su Soldadera.”

One notable exception is a more recent corrido titled “El Rebozo Balaceado” (The Bullet-Riddled Rebozo), about a soldadera who gives her life in Villa’s battle for Torreón, felled on the battlefield with her rifle and her bloody Mexican shawl. It’s sung as a male-female duet by composer Victor Cordero “y su Soldadera.”

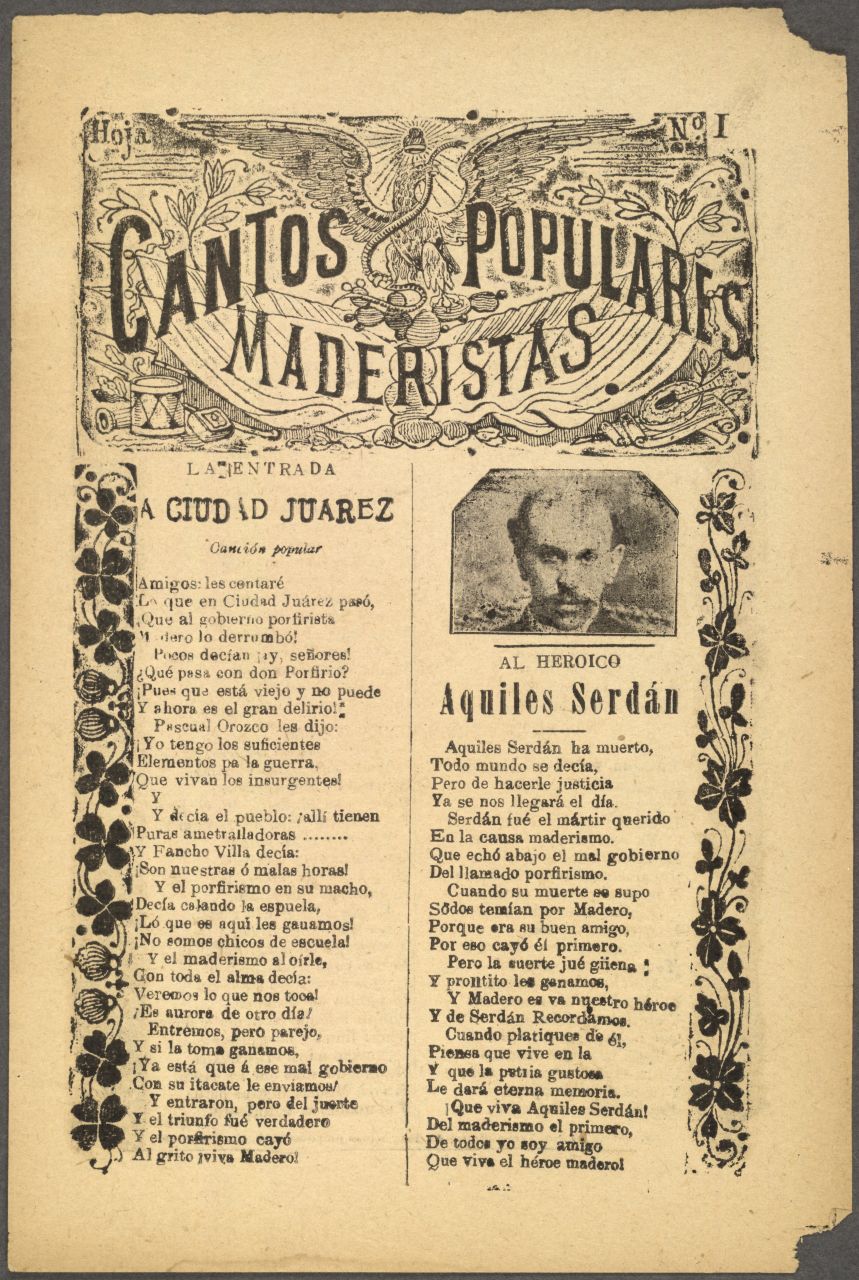

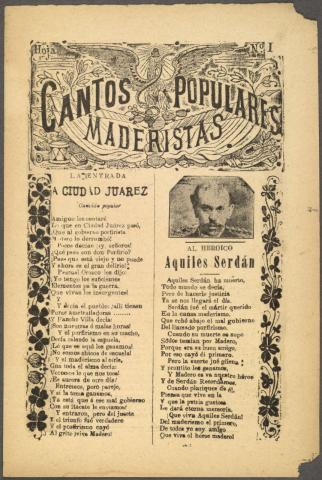

The Frontera Collection contains corridos about other revolutionary figures, such as Emiliano Zapata, Benjamin Argumedo, and Valente Quintero. In a previous blog, I wrote about the fascinating Frontera recordings related to the rise and tragically quick fall of Madero. Some are historic re-enactments of actual events, such as Madero’s triumphant entrance to Mexico City. But there are also two corridos about Madero worth highlighting.

In “El Nuevo Corrido de Madero,” by the duo Camacho y Pérez, Mexico’s first revolutionary president is depicted as a courageous man who, among his first official acts, went immediately to the prisons and released the inmates, presumably held unjustly by the overthrown dictatorship. The bold act establishes Madero’s character in the second verse, and the corrido goes on to tell of the political betrayals and intrigue that eventually cost him his life. In his essay defining the genre, corrido expert and UCLA Spanish professor Guillermo Hernández used this song to illustrate the character of the corrido protagonist, “who generally serves as a model of conduct under extraordinary circumstances.”

The archives contain three recordings of the song, Okeh 16696, Columbia 4863, and Vocalion 8696. They are essentially the same recording made by the duo in Los Angeles around 1930. Manuel Camacho, half of the team, is credited as the author. As with many early corridos, the accompaniment is simply two guitars.

Madero’s heroic death is recounted in another corrido, “El Cuartelazo,” or coup d’état. All three versions in the archives – by Hermanos Chavarría, Dúo Atasoseno, and the duet of María y Juanita Mendoza – tell the same general story, with more or less detail. All of them include the verse in which an opposing army officer, the nephew of deposed dictator Porfirio Díaz, orders Madero to resign or face execution. Madero defiantly refuses, setting up his tragic downfall. Additional verses expanding on Madero’s principled resistance are offered only in the version by Hermanos Chavarría, a longer, two-part corrido on a Columbia 78-rpm disc. This version adds two verses that heighten Madero’s heroism.

Madero les contestó,

“No presento mi retiro.

Yo no me hice presidente,

Fuí por el pueblo elegido.”

Madero answered them,

“I will not resign.

I did not make myself president,

I was elected by the people.”

All versions recount the horror of the ten-day siege to depose the doomed leader, describing fear that gripped the city with scenes of dead and injured on the streets. Curiously, there are variations in the description of which part of the populace reacts with tears. When government forces start bombing the Citadel (La Ciudadela), the Dúo Atasoseno notes that people were crying (“estaba gente llorando”). But the rendition by sisters Juanita and María Mendoza notes only that “the women were crying” in reaction to the same assault: “Otro día por la mañana / las mujeres llorando / de ver la ciudadela / Que la estaban bombardeando.”

Corridos of the revolution remained popular for decades after the civil war subsided. And the topical song continued to capture the Mexican imagination. In 1956, Mendoza, the corrido scholar, devoted an entire book to the ballads of that violent era: El Corrido de la Revolución Mexicana, published by the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Corridos of the revolution remained popular for decades after the civil war subsided. And the topical song continued to capture the Mexican imagination. In 1956, Mendoza, the corrido scholar, devoted an entire book to the ballads of that violent era: El Corrido de la Revolución Mexicana, published by the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

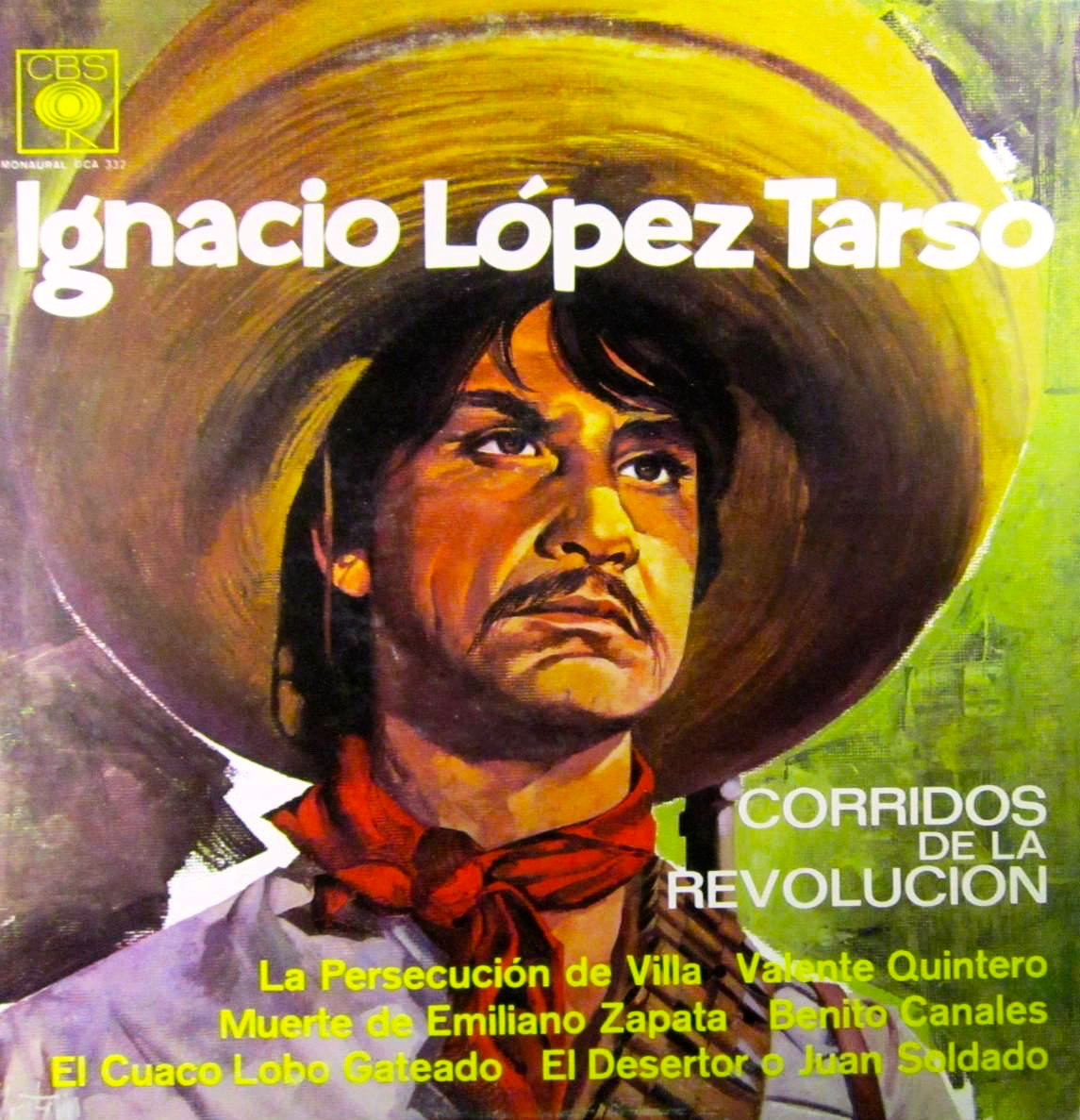

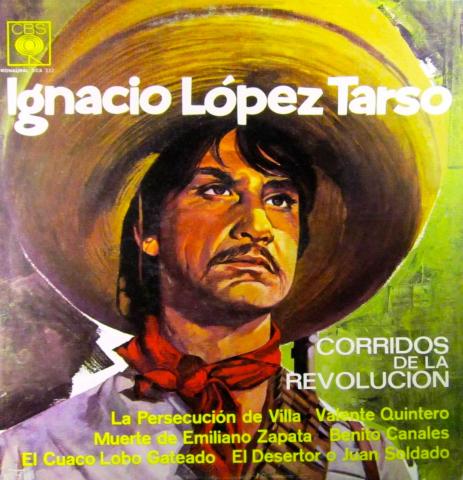

Top Mexican artists, including Antonio Aguilar and Los Alegres de Terán, continued to record albums of corridos well into the 1970s and ’80s, more than half a century after the events. The Mexican actor Ignacio Lopez Tarso became known for his spoken narrations of Mexican revolutionary corridos, recorded in the 1970s with musical accompaniment behind his emotive, baritone delivery.

The Tarso recordings are now available on the streaming service Spotify, a digital development which represents a revolution of another kind.

--Agustín Gurza

Additional reading:

The Mexican Corrido: Ballads of Adversity and Rebellion, Part 1: Defining the Genre

The Mexican Corrido: Ballads of Adversity and Rebellion, Part 2: Border Bandits or Folk Heroes

The Mexican Corrido: Ballads of Adversity and Rebellion, Part 3: Two-Part Corridos

Blog Category

Tags

Images