the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center,

the Arhoolie Foundation,

and the UCLA Digital Library

Part 3: Two-Part Corridos

During the first half of the 20th century, the corrido went from an oral tradition to a recorded, commercial art form. But in making that transition, corrido artists had to adapt their long narrative ballads to the recording technology of the day, primarily the old 78-rpm shellac discs.

During the first half of the 20th century, the corrido went from an oral tradition to a recorded, commercial art form. But in making that transition, corrido artists had to adapt their long narrative ballads to the recording technology of the day, primarily the old 78-rpm shellac discs.

In those early years of the recording industry, before the introduction of the long-playing (LP) record in the 1950s, it was common practice to record corridos in two parts. That’s because only a limited amount of music could fit on one side of a 78-rpm record, which was essentially a single. To tell the whole story, and get to the all-important climax where the protagonist often dies heroically, corridistas had to use both sides of the record. The listener would play side A, which sometimes ended in a cliff-hanger, then flip the record over for the climax on side B.

These double-sided ballads became a special focus of Frontera’s founder Chris Strachwitz. On his record hunts throughout the years, the assiduous collector picked up every two-part corrido he could get his hands on. As a result, the Frontera Collection boasts 183 two-part corridos, one of the largest such collections in the world. In many cases, they are one-of-a-kind items, the only surviving copies of certain songs. (For a complete list of the collection’s two-part corridos, see Appendix I of The Strachwitz Frontera Collection of Mexican and Mexican American Recordings, a guide to collection I co-authored with Strachwitz and Jonathan Clark.)

These double-sided ballads became a special focus of Frontera’s founder Chris Strachwitz. On his record hunts throughout the years, the assiduous collector picked up every two-part corrido he could get his hands on. As a result, the Frontera Collection boasts 183 two-part corridos, one of the largest such collections in the world. In many cases, they are one-of-a-kind items, the only surviving copies of certain songs. (For a complete list of the collection’s two-part corridos, see Appendix I of The Strachwitz Frontera Collection of Mexican and Mexican American Recordings, a guide to collection I co-authored with Strachwitz and Jonathan Clark.)

The discs from this era, especially from the 1920s through the 1940s, represent the golden era of the corrido, which first emerged along the border following the U.S. war with Mexico.

Many of the early oral ballads from the late 1800s – which, as we saw in my last installment, celebrated border bandits and folk heroes – were later recorded as two-part corridos. They include, for example, the “Corrido of Joaquín Murrieta,” a real-life rebel who was captured and beheaded in Northern California during the Gold Rush years.

Often, however, the historical facts of a specific corrido, especially those about ordinary people, remain unknown or unverified. In one rare case, recent research unearthed additional details about events described in a corrido, and even identified the likely composer, who remains uncredited on the record labels.

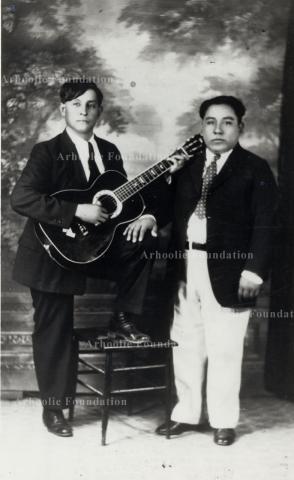

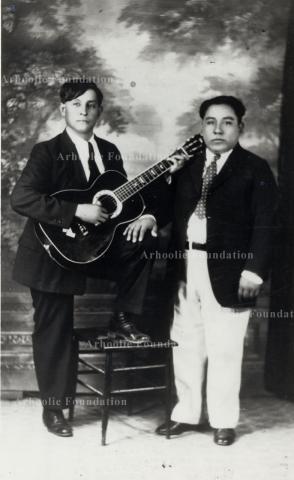

The case involves "Contrabando de El Paso," one of the most notable of the two-part ballads in the collection, considered a precursor to the popular narcocorridos of today. The song is written as the first-person account of a prisoner who describes being transported from El Paso to the federal penitentiary at Leavenworth, Kansas, where he was to serve a sentence for smuggling. The exact type of contraband is not specified, but the song was written at the height of Prohibition (1920–33), when smuggling liquor from Mexico was a booming underground trade. It was first recorded in 1928 by the duo of Leonardo Sifuentes and Luis Hernández, pioneer corridistas from El Paso, Texas.

In a paper published in 2005, the late corrido expert Guillermo Hernandez documented the historical events surrounding the anonymous smuggler on that prison train. Hernandez, a Spanish professor who helped bring the Frontera Collection to UCLA, identified the likely composer as Gabriel Jara Franco, a Leavenworth inmate. Hernandez found records showing that the prisoner had corresponded with Sifuentes, half of the musical duo that recorded the ballad for the New Jersey-based Victor label. Relying on sketchy information in the lyrics, Hernandez even recreated the likely itinerary of the prisoner train, stop by stop. (A short video about Hernandez and his corrido research, produced by the Arhoolie Foundation, is viewable online.)

In a paper published in 2005, the late corrido expert Guillermo Hernandez documented the historical events surrounding the anonymous smuggler on that prison train. Hernandez, a Spanish professor who helped bring the Frontera Collection to UCLA, identified the likely composer as Gabriel Jara Franco, a Leavenworth inmate. Hernandez found records showing that the prisoner had corresponded with Sifuentes, half of the musical duo that recorded the ballad for the New Jersey-based Victor label. Relying on sketchy information in the lyrics, Hernandez even recreated the likely itinerary of the prisoner train, stop by stop. (A short video about Hernandez and his corrido research, produced by the Arhoolie Foundation, is viewable online.)

The Frontera Collection lists dozens of versions of the song, including relatively recent renditions by Los Alegres de Terán (1970) and Lorenzo de Monteclaro (1976), the latter on the Los Angeles-based Fono Rex label. Some use an alternate spelling of the original title, “Contrabando del Paso,” substituting a contraction for the proper name of the Texas border city.

The most significant versions continue to be the early ones, recorded as two-part corridos on 78-rpm discs. The archive lists five such versions on different labels, including the original by Hernández y Sifuentes on the old Victor label with the scroll design and the logo of the gramophone and the dog above the slogan “His Master’s Voice.”

Not all long corridos, however, took advantage of both sides of a disc to tell the full story. In some cases, inexplicably, extended narratives were restricted to one side, truncating the story or eliminating the climax altogether. Such was the case with a recording of the tragic story of “La Delgadina,” a heart-wrenching tale of father-daughter incest. This historic corrido, with direct roots in the romances of medieval Spain, is about a lovely and noble young woman who pays the ultimate price after refusing her father’s sexual advances.

In the version by the Cuarteto Carta Blanca (Vocalion 8677), however, the story ends on one side of the record with the father ordering servants to imprison his daughter for her refusal. Strangely, it ends without ever reaching its tragic conclusion. Instead, side B features the unrelated track, “En el Rancho Grande.”

In the version by the Cuarteto Carta Blanca (Vocalion 8677), however, the story ends on one side of the record with the father ordering servants to imprison his daughter for her refusal. Strangely, it ends without ever reaching its tragic conclusion. Instead, side B features the unrelated track, “En el Rancho Grande.”

Today, new versions and interpretations of “Delgadina” appear on the Internet, a modern-day amplifier of the ancient oral tradition that gave rise to corridos. Several versions are now posted on YouTube, including some by contemporary recording artists such as Irma Serrano and the San Jose–based group Los Humildes.

Ironically, the evolution of technology forced the corrido to get shorter in the last half of the 20th century. Beginning in the 1950s, new versions of old corridos were released as 45-rpm singles, the format that replaced the 78s. But 45s were used primarily to promote hit tracks from LPs. The singles had to be kept short, usually less than three minutes, for radio play. So the old epic tales had to be edited to fit the new medium. Lost were the detail and the drama of the narratives. In other words, the shorter versions don’t tell the whole story

A good example is the corrido of Los Tequileros, one of many ballads about tequila smugglers who thrived along the border during Prohibition, which outlawed alcoholic beverages in the United States during the 1920s. This song, another precursor to the modern narco-corrido, is a simple story about a trio of tequileros who are ambushed and killed by Texas Rangers, pronounced “rinches” in the local vernacular. The confrontation between the smugglers and the Rangers sets up the song’s central drama; the denouement allows the smugglers to die as heroes at the hands of the merciless “rinches.”

In the longer, two-part version by Los Hermanos Chavarria, we learn that a snitch had betrayed the Mexicans, so the Rangers were lying in wait and “spying on them.” (Como estabn denunciados, ya los estaban espiando.) A more recent, shorter version by Los Alegres de Terán, simply says the Rangers “must have known” that the smugglers were coming, with no mention of the snitch that tipped them off.

In the longer, two-part version by Los Hermanos Chavarria, we learn that a snitch had betrayed the Mexicans, so the Rangers were lying in wait and “spying on them.” (Como estabn denunciados, ya los estaban espiando.) A more recent, shorter version by Los Alegres de Terán, simply says the Rangers “must have known” that the smugglers were coming, with no mention of the snitch that tipped them off.

More importantly, the shorter version eliminates some of the crucial dialog considered one of those unique characteristics of the classic corrido. In the long version, the lead Ranger approaches the last smuggler, gravely wounded, and starts interrogating him. The agent asks for his name, and where he’s from.

"Me llamo Silvano García, soy de China, Nuevo León.”

The answer resonates with that defiance and sense of national pride. Though his two partners have been killed and he lies close to death, the last smuggler is still asserting his identity, and bravely accepting his fate.

Silvano con tres balazos, todavía seguía hablando

"Mátenme rinches cobardes, ya no me estén preguntando."

(Kill me, cowardly Rangers, just stop asking me questions.)

In the shorter version, we are told the Ranger walks up to the wounded smuggler, and “seconds later” he’s dead. The interrogation isn’t mentioned, so the response loses its context, and its punch. At almost twice the length, the older two-part version has room for the expanded dialog, thus enhancing the heroic qualities of the smugglers and turning their deaths into a brave act of nationalism and defiance.

Los Tequileros has yet another classic corrido element – the farewell, or despedida. Before saying goodbye, the narrator addresses the Rangers directly, trying to deny them credit for the kill.

No se las recarguen, rinches, por haberles dado muerte

No digan que los mataron. Los mató su mala suerte.

Don’t go bragging, rinches, for having brought them death

Don’t say you killed them. What killed them was their bad luck.

The lasting legacy of these narrative ballads, from oral tradition to YouTube videos, highlights the multi-generational appeal of the Mexican corrido as a genre, now well into its second century. These timeless songs endure because, as Hernandez states in his essay, they “touch the most sensitive chords in lovers of the genre.” And he gives credit to the often anonymous corrido composers, such as the author of “El Contrabando de El Paso,” whom he managed to name after more than half a century.

“Gabriel Jara, although unknown and forgotten, recovers for the rest of us a touch of human existence and sensibility,” Hernandez wrote. “That is, perhaps, all we can ask of art in any time or place.”

--Agustín Gurza

Additional reading:

The Mexican Corrido: Ballads of Adversity and Rebellion, Part 1: Defining the Genre

The Mexican Corrido: Ballads of Adversity and Rebellion, Part 2: Border Bandits or Folk Heroes

The Mexican Corrido: Ballads of Adversity and Rebellion, Part 4: Corridos of the Mexican Revolution

1 Comments

Stay informed on our latest news!

The Importance of Dating Material

by Hilario 'Lalo' ... (not verified), 01/13/2019 - 11:53No dates on the music or any of the written material.

I know it's hard to track down sometimes. Still, I expected some attempt at dating the material. I am trying to date some of the files I have and I understand the frustration of dating the material, but I believe it's a necessary item.

Otherwise, you have an impressive site with lots of excellent song files.