Artist Biography: Los Alegres de Terán

Los Alegres de Terán, a vocal duet founded by a pair of humble migrant workers from northern Mexico, stands as one of the most influential, long-lived and commercially successful regional music acts from the last half of the 20th century. The duo of Tomás Ortiz and Eugenio Ábrego are today remembered as the fathers of modern norteño music, the accordion-based country style that traversed borders as fluidly as its immigrant fans.

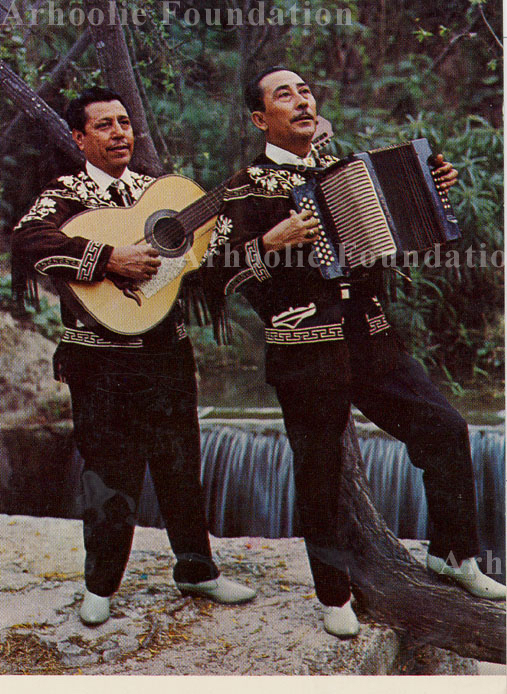

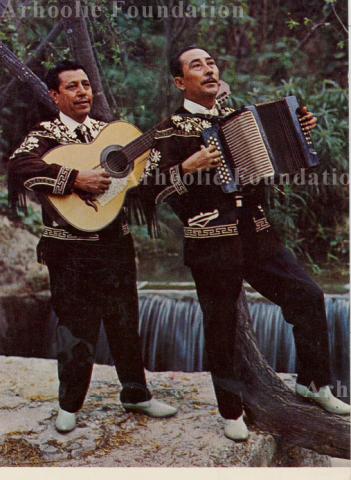

Founded in 1948 in the town of General Terán, Nuevo Leon, about 130 miles from the border with Texas, Los Alegres became the first norteño act to break out of the genre’s regional boundaries in northern Mexico, gaining wide popularity on both sides of the border, from McAllen to Mexico City. The prolific duo wrote scores of songs and recorded over 100 albums, backing themselves on bajo sexto and accordion, while delivering emotional vocals that blended in a warm, natural unison.

Although Ortiz and Ábrego followed in the tradition of popular vocal duets from the 1920s and ’30s, they were the first to combine their harmonizing with the accordion. Until they came along, accordion music was mostly instrumental and vocal duets were primarily backed by guitar accompaniment.

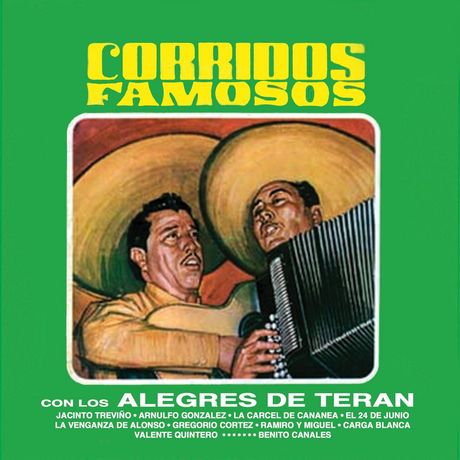

Beyond their singing and playing style, Los Alegres were able to tap into the massive migrant market because they were a part of it. They modernized the themes of the traditional corrido, or narrative ballad, making the music more relevant to migrant workers who were not only moving north across the border into the US but were also flooding urban centers such as Mexico City in the mid-20th century.

“As the first popular norteña ensemble, Los Alegres made an impact that was greatly aided by their ability to tap into the feelings and experiences of the growing Mexican migrant population of the late 1940s and 1950s,” wrote Cathy Ragland in her book, Música Norteña: Mexican Migrants Creating a Nation Between Nations. “The working class community in Mexico embraced (them) because of the group’s ability to merge sophisticated vocal harmonies and arrangements with an updated corrido narrative form that, in addition to love songs, included themes of travel, alienation, and nostalgic images of rural and ranchero life.”

Eugenio Ábrego García was born May 2, 1922, in Rancho de La Soledad, within the municipality of General Terán, a town named for a military hero of Mexico’s War of Independence. Tomás Ortiz del Valle was born two years and one month later, on June 2, 1924, in Terán’s Rancho San Rafael community.

Their full names and birth information are cited on the city’s Facebook page, which includes the most complete profile of the duo available on the web. Other sources, such as Wikipedia, provide scant biographical details. In fact, the group’s Wikipedia page is only a stub (a short article deemed encyclopedically insufficient), which links to a defunct website for the duet. A book-length biography of the band, Alegres de Terán: Vida y Canciones by Francisco Ramos Aguirre, is available only in Spanish and somewhat hard to find. (The book does not appear prominently in Google searches by the band’s name.) This article was compiled from multiple sources, including album liner notes, in both English and Spanish.

Aside from its musical native sons, Terán is considered the birthplace of Mexico’s once dominant political party, the PRI, and was once home to the party’s controversial founder, President Plutarco Elías Calles. From there, it’s approximately a 90-minute drive to the state capital of Monterrey, and approximately 2.5 hours to the U.S. border at McAllen, Texas. That geographic triangle – Terán to Monterrey to McAllen – would be the original base of operations for the two migrant musicians who were destined to make history in their field.

Both Ortiz and Ábrego picked up their instruments at a young age, and started performing around town independently. Depending on the source, the two men met either playing at a bar or at a gathering in a private home. Be that as it may, sources agree they hit it off right away.

“When they improvised a duet at a family fiesta, they felt a certain chemistry,” states a profile at Sabados Rancheros, the website for a Chicago radio program featuring Mexican music. “They were pleased with the ensemble, and thus was born the duet which was named Ábrego y Ortiz.”

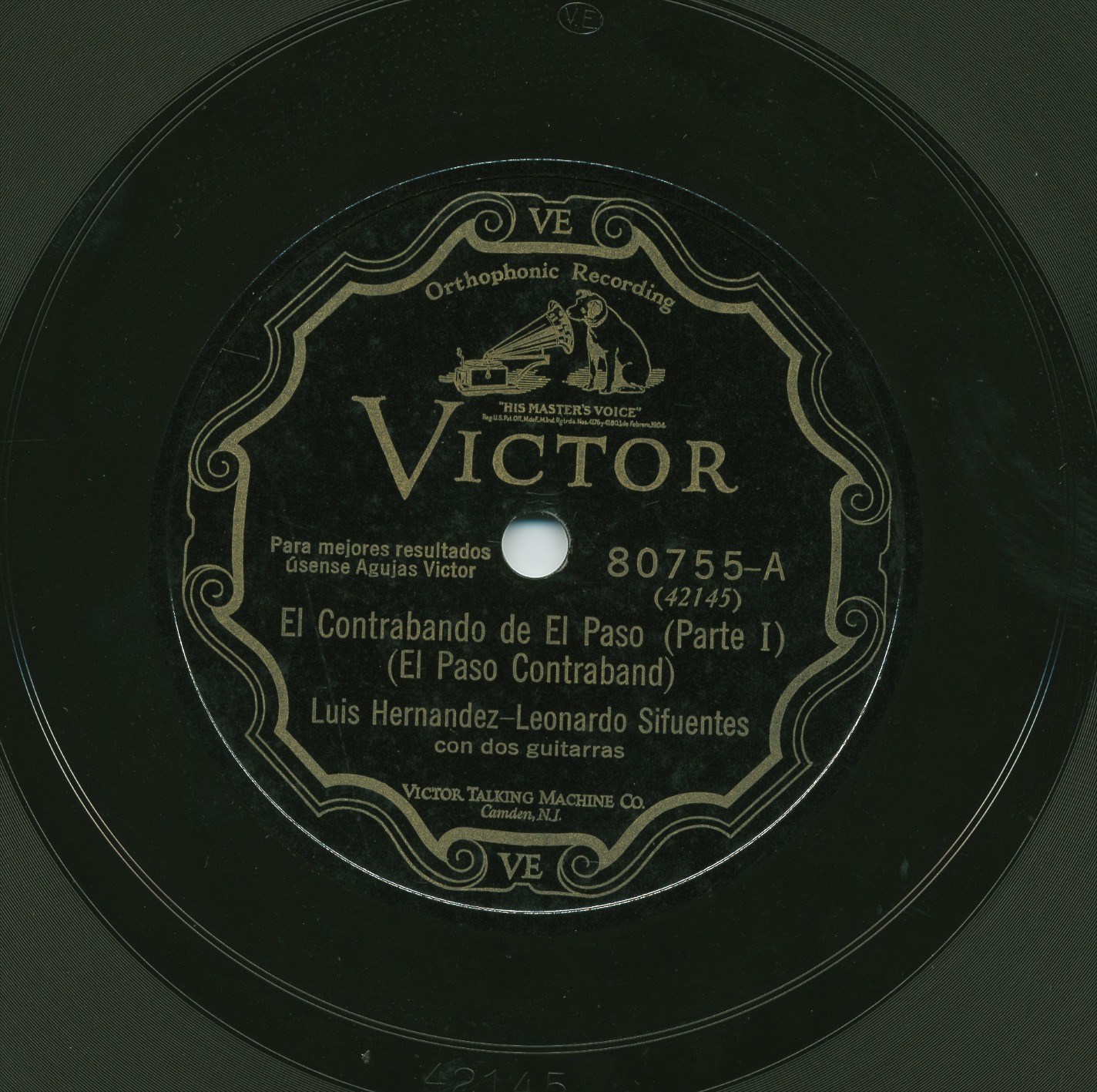

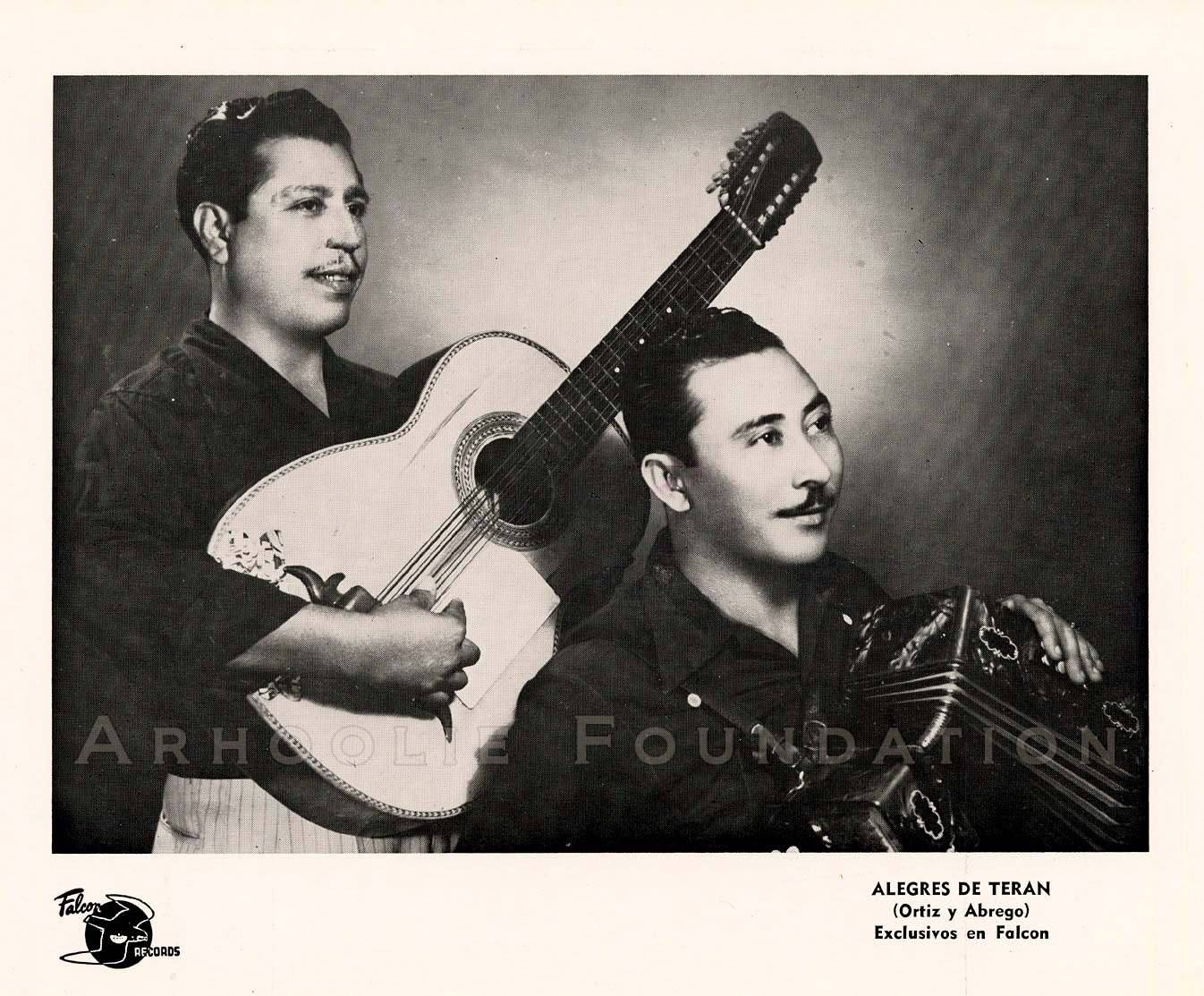

In 1948, the newly minted duo started making the rounds of clubs and cantinas in their hometown’s red-light district (zone de tolerancia). Their crowd-pleasing performances spurred them to travel to nearby Monterrey to pursue their careers. The following year, they made their first recording on the Orfeo label, a 78-rpm single titled “El Corrido de Pepito,” backed by “La Matrera,” a polka composed by Ábrego.

Today, Orfeo discs are extremely rare. The Frontera Collection contains 145 recordings on the label, all 78s, including 25 original tracks by Los Alegres de Terán. In addition, there are works attributed to other incarnations of the duo, such as Ortiz with other partners, as well as one song by Dueto Ábrego, though its members are not identified individually.

Although tales about how bands got their names are often apocryphal, the Facebook bio tells a plausible story about how Dueto Ábrego y Ortiz became The Happy Ones from Terán.

The duo was making an appearance on a radio program called “El Pregonero del Norte,” broadcast on XET, a Monterrey radio station that was key to their early success, with a signal reaching the border and beyond. While on the air, the two artists broke out in laughter, prompting popular deejay Juan Cejudo to ask what was so funny. The answer: “That’s just the way we are, the people from Terán, very happy. (Es que así somos los de Terán, muy alegres).” From that moment, the deejay christened them Los Alegres de Terán.

Los Alegres were no overnight sensation. It would take years for them to score a major hit and their popularity rose “at a desperately slow rate” (con desesperante lentitud), as another radio website put it. Meanwhile, on bus rides from Terán to Monterrey for radio appearances, they would still play for fellow passengers and pass the hat for tips.

In 1950, Los Alegres moved to Reynosa, Tamaulipas, a border town directly across from McAllen, a Texas town that was then emerging as a focal point for the border music industry. In 1948, the same year Los Alegres came together, Arnaldo Ramírez had founded Falcon Records, the McAllen-based label that would become a major player in the field. It didn’t take long for the label and the duo to join forces, setting Los Alegres on the path to stardom.

Los Alegres had their first major hit on Falcon in 1953 with “Carta Jugada,” about a spurned man who discovers that the object of his hopeless love was, as the titles suggests, like a card that had already been played. Their early Falcon albums, Los Ojos de Pancha and Más y Más Corridos, are considered classics of the genre.

“ ‘Carta Jugada’ reveals some of the stylistic nuances employed by the group to update the traditional border corrido form, rendering it more musically expressive,” writes Ragland, associate professor of ethnomusicology at the University of North Texas. “Ortiz and Ábrego sing in parallel thirds, but with the second voice sung in a high register that produces a vocal strain, thus bringing more emotion to the song and its subject matter.”

The regional success of Los Alegres coincided with the growth of the Mexican record industry in Mexico City. The duo – with its blend of country and romantic styles showcased in polished arrangements – drew the attention of producers in the capital, who historically had looked down on the working-class music of the border regions. In 1956, according to the Facebook biography, famed composer and producer Felipe Valdez Leal signed Ortiz and Ábrego to a contract with Discos Columbia, the Mexican CBS affiliate and a Mexican music powerhouse.

Musical trends in the capital were driven at the time by wider cultural forces in a country rapidly developing within a proud, post-revolutionary climate. Record executives sought out acts that reflected a modern, nationalistic, urban ethos. Los Alegres, who had already modernized the rustic, rural sound of norteño music, fit the bill.

At Columbia, Los Alegres had graduated to the big leagues, marketed nationally as “the first stars of norteña music.”

“Los Alegres knew how to connect with their local audiences,” writes Ragland, “but they were also aware of their role as representatives of a regional genre that was compelled to compete with the urban popular music singers” marketed by major labels and movies in mid-century Mexico.

In the country’s highly centralized capital, the duo became beneficiaries of the industry’s powerful promotional machine, which vastly enhanced their international profile. They joined the famous “caravanas artísticas”—a caravan of stars composed of a rotating bill of major acts that hit the road as a touring attraction. The lowly country musicians found themselves rubbing shoulders and sharing stages with first-rate luminaries such as José Alfredo Jiménez, Miguel Aceves Mejía, Las Hermanas Huerta, Chelo Silva, Lola Beltrán, and others.

Traveling with the caravans throughout the late 1950s and early ’60s, Los Alegres appeared at premiere venues, from the capital’s Teatro Blanquita to The Millon Dollar Theatre in Los Angeles. They also made cross-genre inroads, invited as guests at the first international polka festival held in Chicago in the early 1960s, where they shared the ethnic bill with other immigrant musicians from Eastern Europe, Germany, and elsewhere.

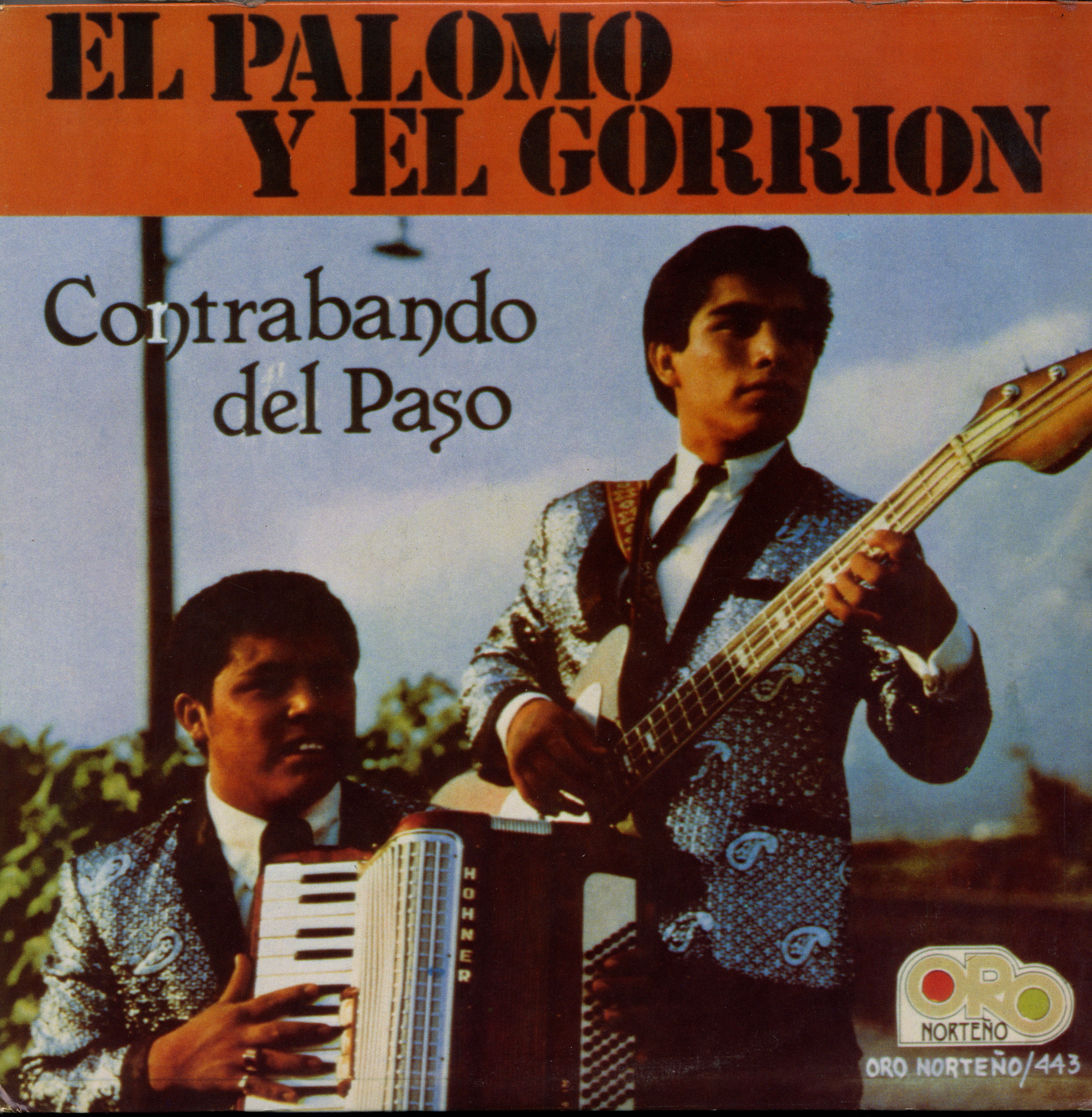

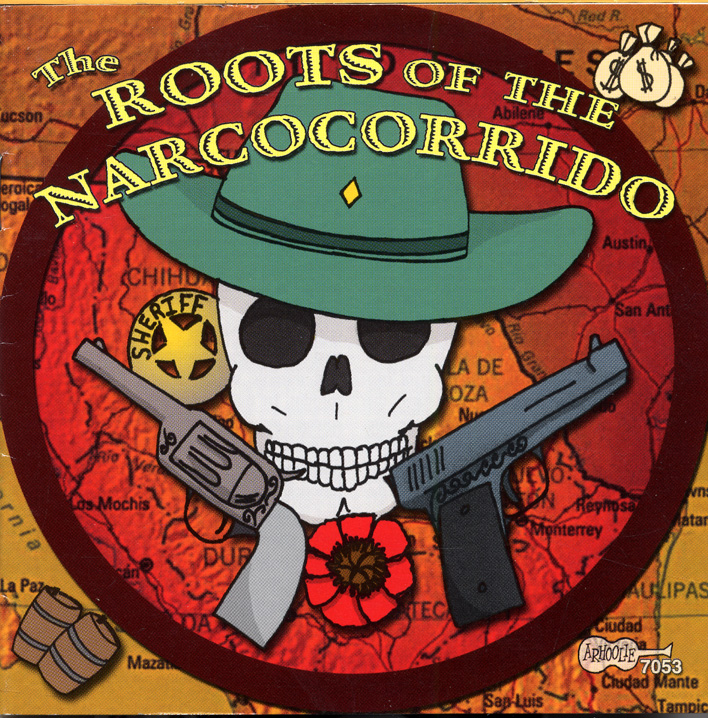

At the same time, Los Alegres made their first forays into film. They appeared in 1962’s “Pueblito” (Little Village), by famed director Emilio Fernandez, though they are uncredited on the International Movie Database. They also appeared as musical performers in “El Contrabando del Paso” (1980), and later in “El Güero Estrada,” based on a corrido about a “fearsome” criminal who robbed and killed innocent immigrants as they crossed the border, then threw their bodies in the river.

Over a career that spanned four decades, Los Alegres recorded more than 100 albums, according to conservative estimates. They scored a long line of hits, including "El Ojo de Vidrio," “El Golpe Traidor,” “Moneda Sin Valor,” “Dos Gotas De Agua,” “La Mesera,” “Alma Enamorada,” and “Entre Copa Y Copa,” to name just a few.

The duo split up for two years in mid-career, but they happily reconciled. They continued recording and touring, pushing norteño music to global heights with fans as far away as Japan, Iraq, Spain, and even parts of Africa.

They received many honors as ambassadors of their proletariat folk style. Their hometown was especially appreciative that the duo carried its name proudly around the world. And to show its own appreciation, beginning in 1964, Los Alegres performed an annual free concert on Mexican Independence Day in the central plaza of General Terán, with proceeds going to the city for social works.

Los Alegres marked their 25th anniversary with fanfare in 1974. They were the guests of honor at a state banquet held by the governor of Nuevo Leon. To mark the occasion, Falcon Records released a comprehensive, three-record set entitled “Bodas de Plata,” using the Spanish term for silver wedding anniversaries, befitting this long musical marriage.

The duo was also feted that year back in Terán. Their hometown established a symbolic sister-city relationship with Mission, Texas, where the mayor at the time was none other than Falcon founder Arnaldo Ramírez.

In 1980, a street was named in their honor, Avenida Los Alegres de Terán, in their hometown. Today, an entire neighborhood also carries their name, Colonia Alegres de Terán, with its own zip code (64700). And in 2011, the city fathers erected full-size statues of the duo playing their accordion and 12-string guitar and elevated on a stone pedestal in the city’s Plaza Juarez.

Three years later, on the duo’s 35th anniversary, Falcon Records organized a major tribute held at the landmark Biltmore Hotel in downtown Los Angeles. That same year, 1983, Los Alegres de Terán were inducted into the Conjunto Music Hall of Fame in Texas.

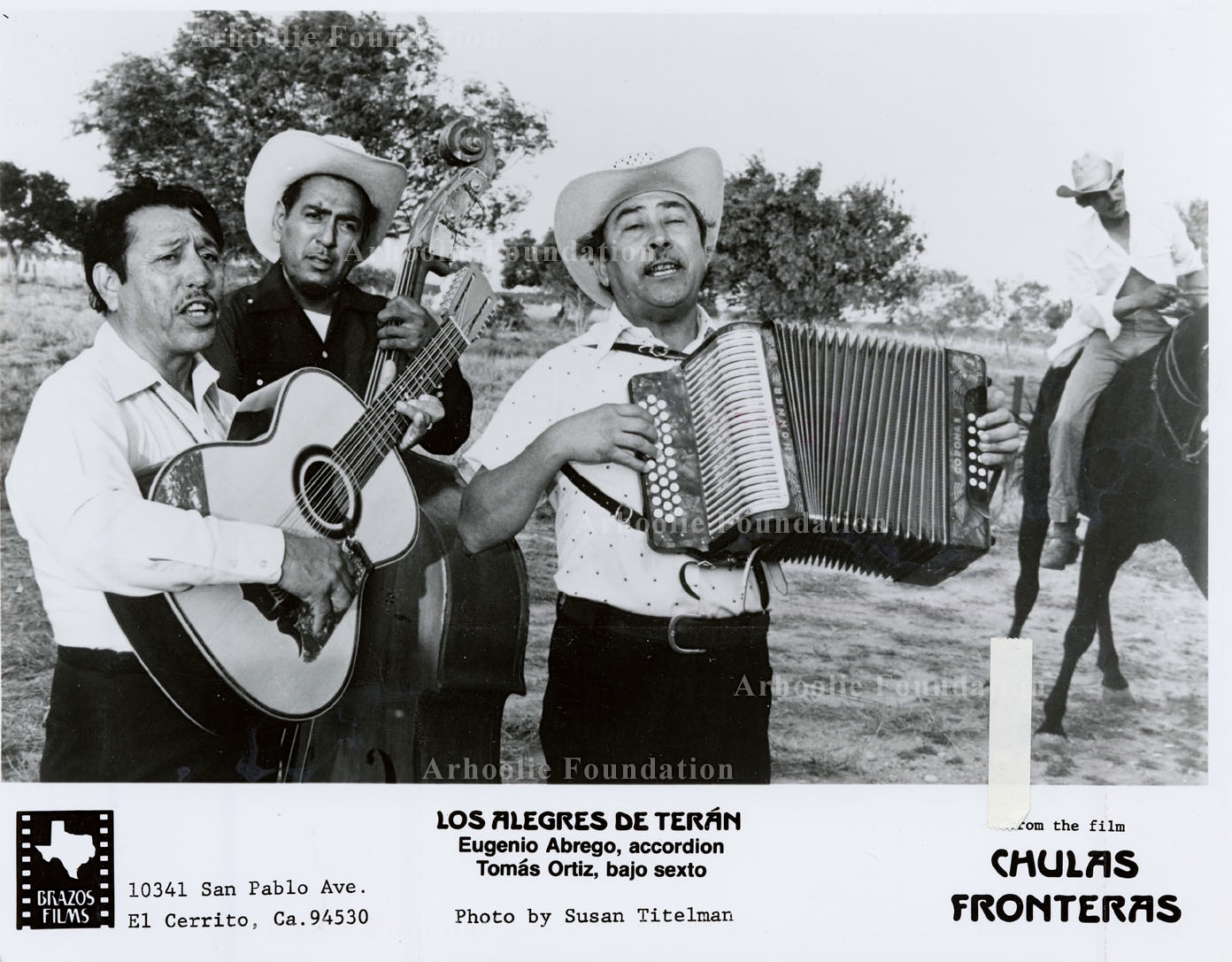

Chris Strachwitz, founder of the Frontera Collection, also documented the cultural importance of Los Alegres over the years, as record collector, music executive, and film producer. The duo was prominently featured in Strachwitz’s 1976 documentary about border music, Chulas Fronteras, directed by Les Blank. Twenty-eight years later, his label, Arhoolie Records, released a compilation of the duo’s earliest recordings on the Falcon label, Los Alegres De Terán, Grabaciones Originales: 1952–1954, introducing the band and its music to a new generation. Those tracks were culled from Strachwitz’s own archives, where he had amassed hundreds of recordings by Los Alegres, now accessible to the public through the Frontera Collection website.

The duo’s remarkable run came to an end with the death of Ábrego in 1988. Ortiz survived him by 19 years, continuing to perform with another partner, Leobardo Pérez, on accordion and vocal harmonies. Ortiz died in 2007, in Edinburg, Texas.

Even today, almost 40 years after the duo’s demise, Los Alegres remain revered and beloved by fans. With feet firmly planted on both sides of the border, they became working-class heroes for fans who, like them, were always on the move.

“As migrant workers and folk musicians, Los Alegres represented norteño culture and peasant life on many levels,” writes Ragland. “Their music reflected the nomadic lives of working-class Mexicans, and they were viewed as traveling workers, crossing to the other side when necessary in an effort to take care of their families.”

– Agustín Gurza

Blog Category

Tags

Images

Conjunto music, the accordion style so popular with Mexican Americans throughout the Southwest, comprises a cornerstone of the Frontera Collection. Yet conjunto as such does not appear on the list of Top 20 genres compiled for my

Conjunto music, the accordion style so popular with Mexican Americans throughout the Southwest, comprises a cornerstone of the Frontera Collection. Yet conjunto as such does not appear on the list of Top 20 genres compiled for my