The New Song of the South

Editors' note: We extend our heartfelt prayers to everyone affected by Hurricane Harvey.

When we consider where Latinos live in the U.S., we don’t usually think of states in the Deep South. We think of California, Texas, and New York; not Mississippi, Georgia, or Alabama.

Census reports, as of 2012, show that the states with the highest percentage of Latino residents are all in the West and Southwest, followed by Florida, New York, New Jersey, and Illinois to round out the Top 10. But if you rank states where the Latino population is growing the fastest, 8 of the top 10 spots are taken by Southern states. And each of those states has at least doubled its Latino demographic between 2000 and 2010.

Big demographic shifts are often accompanied by cultural consequences: new foods, new customs, and new music, not to mention new conflicts. So it’s no surprise that there is also a growing interest in Latino culture among Southerners who are making room for their new neighbors.

Big demographic shifts are often accompanied by cultural consequences: new foods, new customs, and new music, not to mention new conflicts. So it’s no surprise that there is also a growing interest in Latino culture among Southerners who are making room for their new neighbors.

At the historic University of Mississippi at Oxford, one group is specifically devoted to exploring these cultural changes. The Southern Foodways Alliance (SFA), based at the university’s Center for the Study of Southern Culture, uses film, oral histories, the written word and stage events to document “the diverse food cultures of the changing South.”

In light of the troubling violence linked to the recent demonstration by white supremacists in Charlottesville, Virginia, the group’s mission statement sounds a needed note of acceptance: “Our work sets a welcome table where all may consider our history and our future in a spirit of respect and reconciliation.”

I’m proud to announce that I have been invited to participate in the 20th annual Southern Foodways Symposium, October 5–7 in Oxford, Mississippi. The theme of the cultural and culinary confab: “El Sur Latino.”

Though food, glorious food, will be the central focus of the gathering, music is also on the agenda. As editor of the Frontera Collection website, I’ll be speaking on the corrido, which is a primary focus of this archive. I’ll be joined by my colleague Gustavo Arellano, editor of the OC Weekly and author of the book Taco USA: How Mexican Food Conquered America.

Though food, glorious food, will be the central focus of the gathering, music is also on the agenda. As editor of the Frontera Collection website, I’ll be speaking on the corrido, which is a primary focus of this archive. I’ll be joined by my colleague Gustavo Arellano, editor of the OC Weekly and author of the book Taco USA: How Mexican Food Conquered America.

A man of many hats, Arellano is also a contributor to a section on the AFA’s website enticingly called “Gravy,” which features a collection of stories about the changing American South. His recent article “Song of El Sur” explores some of the Mexican-American music that features a Southern setting.

Arellano contacted me a few weeks ago to inquire about one such song from the Frontera Collection. It’s a rare, 78-rpm recording called “Enganche del Mississippi,” by Dúo San Antonio, recorded in the 1930s. He calls it “the oldest known Mexican song set in the South.” The title, which roughly translates as “The Mississippi Job,” uses a Spanish slang term for job or gig, but the word “enganche” formally means “hook.”

The double meaning suits the story. This short corrido is about Mexican workers who happily hop on a train in Texas, hired by a contractor (“enganchista”) for work in another state. At a stop in Houston, one man says he’d like to get off and stay. He receives this angry retort: “Why do you want to stay, seeing as you’ve been hooked?”

The song suggests the workers are not only trapped, but also not quite sure of their destination. When the train leaves Houston (at 2 a.m.), one of them asks the contractor if they’re going to Louisiana. No, he’s told, they’re passing through Louisiana and headed straight to Mississippi.

Unlike typical corridos, this one has no lesson or moral at the end. The duo signs off leaving us to imagine what happened to the train and its passengers. But for Arellano, the song presents a clear case of worker exploitation bordering on indentured servitude. It’s also an example of how corridos clue us into history.

“‘Enganche del Mississippi’ stands as an extraordinary account of Mexicans in a place and era barely documented by academics, let alone depicted in popular culture,” he writes.

“‘Enganche del Mississippi’ stands as an extraordinary account of Mexicans in a place and era barely documented by academics, let alone depicted in popular culture,” he writes.

Arellano mentions two other songs of woe that are linked, at least in passing, to Louisiana. One is “Canto del Bracero” (The Bracero’s Song), a 1950s tune by Mexican star Pedro Infante that laments the “sad life” of a temporary worker. The other is “La Tumba Del Mojado” by Los Tigres del Norte, about a fearful immigrant who lives in a basement in Louisiana because he’s a “mojado” (wetback): “I had to bow my head [in deference] to get my week’s pay.”

These songs are typical of working-class corridos, regardless of geographic setting. It’s much more of a challenge to find songs that are set in the South and refer to both food and Latinos.

The Frontera Collection includes a tasty buffet of songs with food as a topic, about two dozen recordings in styles ranging from merengue to cumbia. None are set in the American South, but many have a Caribbean twist, at least rhythmically. They include “Las Enchiladas,” “Menudo,” “Pico de Gallo,” “La Rajita de Canela” (The Slice of Cinnamon), and “Sopa de Pichon” (Pigeon Soup). There’s also a humorous song from Puerto Rico’s famed country singer Chuito El De Bayamon, whose gluttonous protagonist eats everything in sight but never seems to get his fill: “Me Quedé con Hambre” (I’m Still Hungry).

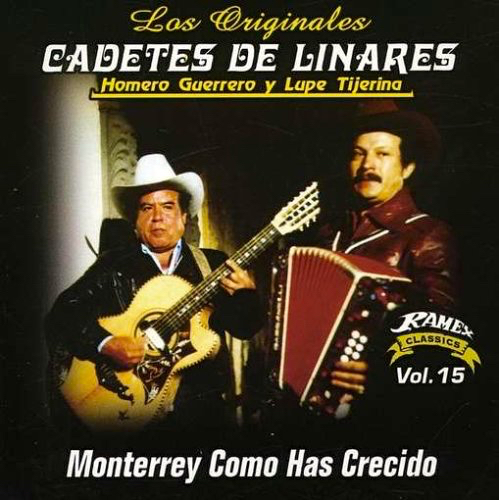

Arellano believes more songs about Latino food and the South will soon be on the menu. I agree. As the Latino population continues to grow in that region, so will its level of cultural expression. Just consider the array of presenters scheduled for the Foodways Alliance Symposium. They include an Ecuadoran pastry chef, a Mexican-American poet, a Guatemalan food journalist with NPR, a Venezuelan chef from Atlanta, an owner, also Venezuelan, of a Caribbean restaurant in Memphis, and the owner of an Atlanta taquería that “combines the traditions of his native Monterrey, Mexico, and his adopted American South.”

Also on the program will be a trio of women musicians from Los Angeles who form the band La Victoria, which combines mariachi music and social activism. The band will close the symposium with a live performance, featuring new corridos written especially for the event.

Also on the program will be a trio of women musicians from Los Angeles who form the band La Victoria, which combines mariachi music and social activism. The band will close the symposium with a live performance, featuring new corridos written especially for the event.

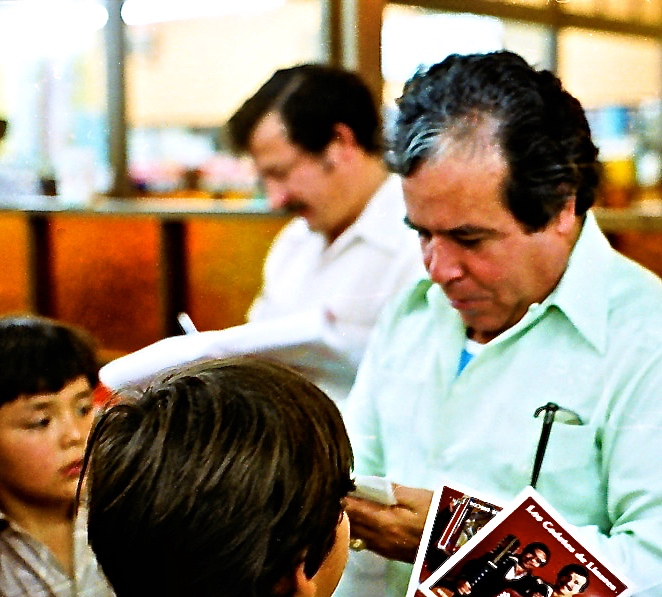

Vaneza Marie Calderón, who plays guitarron for the group, consulted the Frontera Collection this week as part of the research in writing the new corridos. I met her at the library of UCLA’s Chicano Studies Research Center, where the public can access complete songs in the Frontera archive, rather than just the 60-second snippets accessible from computers off-campus. I left the young musician at the computer, headphones on, carefully taking notes while listening to “Enganche del Mississippi,” the original corrido of the Mexican South.

“As Mexicans have made the South their permanent, instead of temporary, home, more tunes are beginning to incorporate it as a setting,” Arellano concludes. “This new wave is still in its infancy. A handful of twenty-first-century corridos talk horses and ‘los derbies de Kentucky,’ a nod to the Mexican-Americans who work in Kentucky’s horse-racing industry. Food is also becoming part of the conversation.”

That simply whets my musical appetite.

- Agustín Gurza

Tags

Images