the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center,

the Arhoolie Foundation,

and the UCLA Digital Library

Recordings are more than just entertainment. They are windows on a culture. In the voice of artists, songs give us a glimpse into what people think and feel in a particular time and place. We hear it in Mississippi Delta blues, the Argentine tango, San Francisco ’60s rock, and a specialty of this archive, the Mexican-American corrido of the early 20th century in the Southwest United States.

There are more than 4,000 corridos in the Frontera Collection, and many tell tragic tales of the borderlands, often reflecting the immigrant experience. On that score, they are still especially relevant today, nearly 100 years later, as Mexican immigration has become a hot-button issue in the presidential election. A prime example is the work of Los Hermanos Bañuelos, a prolific guitar duo that recorded right here in Los Angeles during the 1920s and ’30s.

The Bañuelos brothers, Luis and David, left a trove of socially relevant, often satirical recordings that touched a sensitive nerve in the Mexican-American community at a time when discrimination and even hatred were overt. Because they recorded in the 78-rpm era, when discs could accommodate just one song preside, the duo made a number of two-part corridos, with stories that started on Side A and finished with the climax on Side B. Many of these recordings are listed, with recording dates and locations, in the authoritative discography by Richard K. Spottswood.

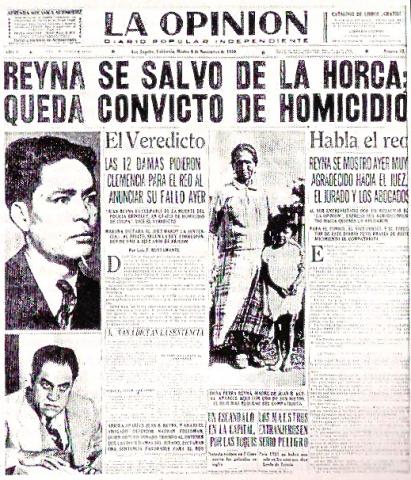

One of their most famous tunes, “El Lavaplatos” (The Dish Washer), contains much of the biting, bitter satire that marked the duo’s work. This two-part corrido (Vocalion 8349) tells the first-person story of a Mexican immigrant who seeks success in Hollywood but finds only menial labor and dashed dreams, and returns to Mexico more broke than before. Los Hermanos Bañuelos also shed light on police brutality and discrimination in another song, “El Corrido de Juan Reyna” (Vocalion 8383), about a celebrated criminal trial one might call the Rodney King case of its day. The song, written by Luis, recounts the case of Reyna, a young Mexican-American foundry worker who shot and killed a police officer while in custody. Reyna, who claimed self-defense and alleged police had used racial insults against him, later killed himself in San Quentin prison. Other notable songs by the duo telegraph the topic in their titles: “El Deportado” (The Deportee), “Los Prisioneros de San Quintín” (The Prisoners of San Quentin), and the seminal narco-corrido “El Contrabando Del Paso” (The El Paso Contraband).

One of their most famous tunes, “El Lavaplatos” (The Dish Washer), contains much of the biting, bitter satire that marked the duo’s work. This two-part corrido (Vocalion 8349) tells the first-person story of a Mexican immigrant who seeks success in Hollywood but finds only menial labor and dashed dreams, and returns to Mexico more broke than before. Los Hermanos Bañuelos also shed light on police brutality and discrimination in another song, “El Corrido de Juan Reyna” (Vocalion 8383), about a celebrated criminal trial one might call the Rodney King case of its day. The song, written by Luis, recounts the case of Reyna, a young Mexican-American foundry worker who shot and killed a police officer while in custody. Reyna, who claimed self-defense and alleged police had used racial insults against him, later killed himself in San Quentin prison. Other notable songs by the duo telegraph the topic in their titles: “El Deportado” (The Deportee), “Los Prisioneros de San Quintín” (The Prisoners of San Quentin), and the seminal narco-corrido “El Contrabando Del Paso” (The El Paso Contraband).

The theme in these and other corridos comes down to the mistreatment of Mexican-American immigrants in the United States. At one level, these are tragic songs about wounded national pride, and about those considered heroes, like Reyna, who stand up to defend it. The lyrics of the Reyna corrido unmistakably make the case: Insulting him insulted Mexico (Porque al insultar a Reyna/ A México se insultó) and he gave his life to defend his dignity and his nationality (Adiós Juan Reyna / Supiste defender tu dignidad, / Y hasta tu vida expusiste / Por tu nacionalidad.)

More than 80 years later, it’s easy to see a parallel dynamic in response to insulting comments about Mexican immigrants made in the current presidential race by Republican front-runner Donald Trump. (There’s even a modern corrido skewering Trump, by a trio called Tres Tristes Tigres.)

One song, “Adios, Estados Unidos” (Goodbye, United States), contains all the elements of the immigrant experience – defiance, disillusionment, deportation, and defense of national honor. The two-part corrido lays out in detail the humiliation encountered by immigrants from the moment they try to enter the country from Mexico. Of course, in those days, getting permission to cross the border was a walk in the park, compared to the insurmountable walls faced today. In fact, in the 1920s, Mexicans were welcomed as workers and exempt from immigration quotas. Many came across legally every day to work.

That doesn’t mean it was safe for the migrants, or good for their self-esteem. In one verse, the immigrant/protagonist mentions that he balked when ordered to the showers, a common practice at the border in the early 20th century. The migrant refuses because he says he already took a bath at his hotel, which rings with a sort of naïve innocence. But the border agent insists, saying he can go to the showers or he can “go to hell,” a phrase pronounced with such a thick accent in the song that it’s almost unintelligible, which makes it funny, but pathetic. Since the migrant doesn’t speak English and doesn’t understand the choice he was given, he says “yes,” sparking derision from the border guard (“el güero aquel se reía”). In the end, he winds up in the showers, anyway.

Here’s the episode as described in three verses:

De allí me fui a la frontera,

Fue mi primer desengaño.

Para principios de cuentas

Me despacharon al baño.

Yo les dije, “No, señores,

Ya me bañé en el hotel.”

Me dijeron, “You se baña,

Si no quiere, go to hell.”

Yo el “go to hell” no entendía

Por no hablar nada de inglés.

Y el güero aquel se reía

Cuando yo le dije, “Yes.”

The gauntlet Mexicans faced at the border was no laughing matter. They had to strip and then were sprayed with a cyanide-based pesticide, known as Zyclon B, as a treatment for lice. It was the same toxic substance later used in Nazi concentrations camps, according to historian David Dorado Romo. The El Paso native has written a new book about riots that erupted in 1917 as protests to the ignominious procedure imposed at the border with Ciudad Juarez. The author first heard of the so-called “Bath Riots” from his great-aunt, who worked as a maid in El Paso. She had been regularly subjected to the humiliating disinfecting process, which made her feel like a “dirty Mexican.”

So this first impression of the United States was a far cry from the golden dream immigrants had imagined. In the song, the protagonist tells us that he had sold all his belongings back home in Mexico to find his fortune in the land where people scooped up money with a broom. Despite the initial humiliations at the border, he forged ahead, determined to reach the place where, people back home had said, there was “money by the piles.”

Crucé por fin la frontera

Tras muchas humillaciones.

Quería llegar hasta el sitio

Donde hay dinero a montones.

But at the start of Part 2 on the B side of the record, he soon realizes his quest would be like looking for the proverbial pot of gold. You’ve got to sweat to put food on the table, he notes, and Mexicans are given only the hardest jobs.

Para sacar los frijoles

Hay que sudar mucho, hermanos

Solo trabajos muy duros

Nos dan a los mexicanos.

The next verses feature interesting though also perplexing observations. Unlike other songs that blame gringos for the discrimination, here the protagonist blames Mexicans themselves for their failure to assimilate. That’s not a bad thing in itself. Mexicans, the narrator notes, keep their citizenship “like good patriots.” They’re not like people of “other races” who betray their flags and become Americanized. And he concludes with this odd couplet: “That is why here, the Mexican has a very dark destiny, because he is not American, like the Filipino is.”

Pero el chicano, señores,

Trabaja con alegría,

Y guarda cual buen patriota

Su amada ciudadanía.

En cambio las otras razas

Luego se ciudadanizan.

Traicionando su bandera,

Luego se americanizan

Por eso aquí el mexicano

Tiene muy negro destino,

Porque no es americano

Como lo es el filipino.

The Filipino reference comes out of left field. But it reflects the kind of inter-ethnic conflicts that appear frequently in other Mexican recordings of the era, as described in “Gringos, Chinos, and Pochos: The Dialectics of Intercultural Conflict in Mexican Music,” a chapter in my book about the Frontera Collection. In this case, the song goes on to describe Filipinos as shameless and ugly people (“desgraciados tan feos”) who traffic in prostitution with American women (“comprando y vendiendo güeras”).

After that disagreeable detour, the song returns to the immigrant’s story. The man still can’t find work because he’s not a citizen. He then gets deported as a result of this “nasty crisis,” a possible reference to the Depression-era deportation and expulsion of Mexican workers to protect jobs for U.S. citizens. Naturally, he leaves with his head high, never having “betrayed my national flag.”

The final verse drips with bitterness about the man’s broken dreams. To those who stay behind, he “leaves this song as a souvenir,” along with “the broom I used to sweep up the money.” He ends with a sarcastic slam of the door: “How well we have been treated in this foreign country.”

Les dejo como un recuerdo

Esta sentida canción.

El tren ya va caminando,

Me llevan a mi nación.

También les dejo mi escoba

Con la que barrí dinero.

Ay, qué bien nos han tratado

En este país extranjero.

As I said, the theme still resonates. But there is one big difference with Mexican-American immigrants nowadays. They see no shame in staying here, becoming citizens and casting their votes in American elections. That is a trend that may have a huge impact on this year’s election outcome, diminishing the chances of any presidential candidate who chooses an anti-immigrant platform.

-Agustín Gurza

0 Comments

Stay informed on our latest news!

Add your comment