Artist Biography: Fred Zimmerle and His Trio San Antonio

Fred Zimmerle (1931-1998) was born in San Antonio of German and Mexican ancestry, a heritage that embodied the cultural fusion of the border region of South Texas. He became one of the most popular and influential acts in the highly competitive conjunto scene in post-war San Antonio, beloved by fans and respected by peers as a historic figure.

influential acts in the highly competitive conjunto scene in post-war San Antonio, beloved by fans and respected by peers as a historic figure.

His grandfather, Fritze Zimmerle, was a German immigrant who spawned an entire clan of musicians, including Fred’s father, Willie, who played accordion while his mother backed him on guitar. Immersed in that musical environment, Fred learned to play guitar, harmonica, and accordion by age ten, and he landed his first paid gig five years later, playing guitar at a wedding with his uncle, Jimmie.

The roster of relatives who were also musicians included his brothers, Henry (guitar) and Santiago (bajo sexto), two other uncles, Felix (fiddle) and Cecilio (guitar), and his sister Caroline who was a singer. Fred’s son, Larry Zimmerle, backed up his father on several recordings and later played with Los Pavos Reales, a popular South Texas conjunto. His nephew, Nick Villareal (born Nicolás Zimmerle Villareal II), gained fame as an accordionist and songwriter. And his aforementioned brother, Henry Zimmerle Sr., also became a prominent figure on the San Antonio conjunto scene, along with his son, Henry Jr.

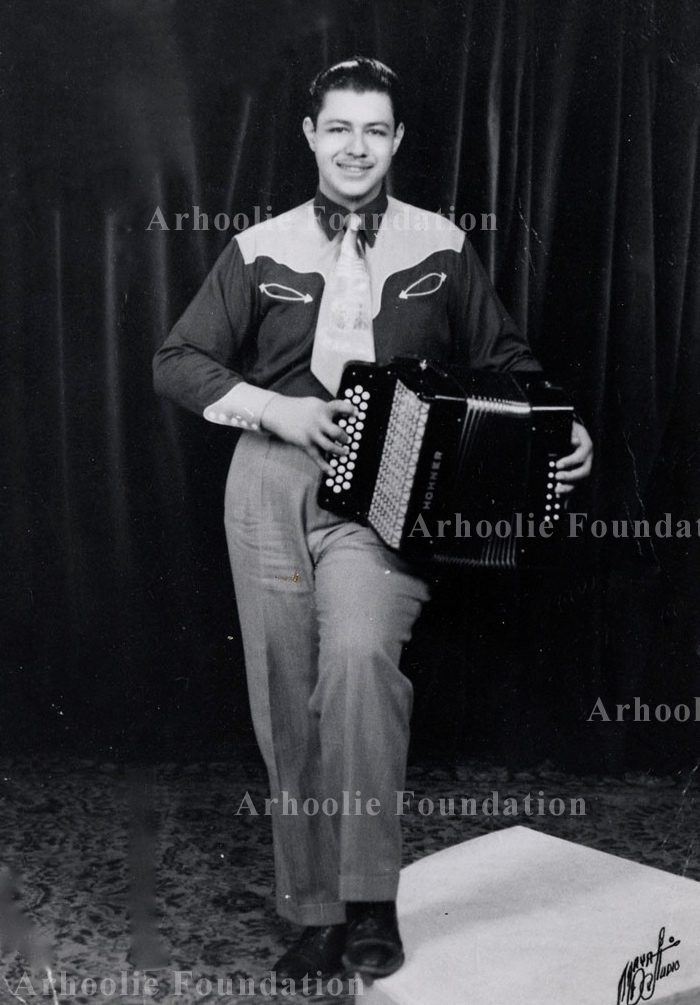

Fred Zimmerle was still in grammar school when he fronted his first band, a harmonica combo. Shortly after the end of World War II, when he was still in his early teens, he founded the original Trio San Antonio, a group he helmed for half a century until his death in 1998. At around the same time, circa 1946, the young musician and his budding ensemble recorded their first tracks for RCA. He then went on to record more than 250 songs during his career, many his own compositions.

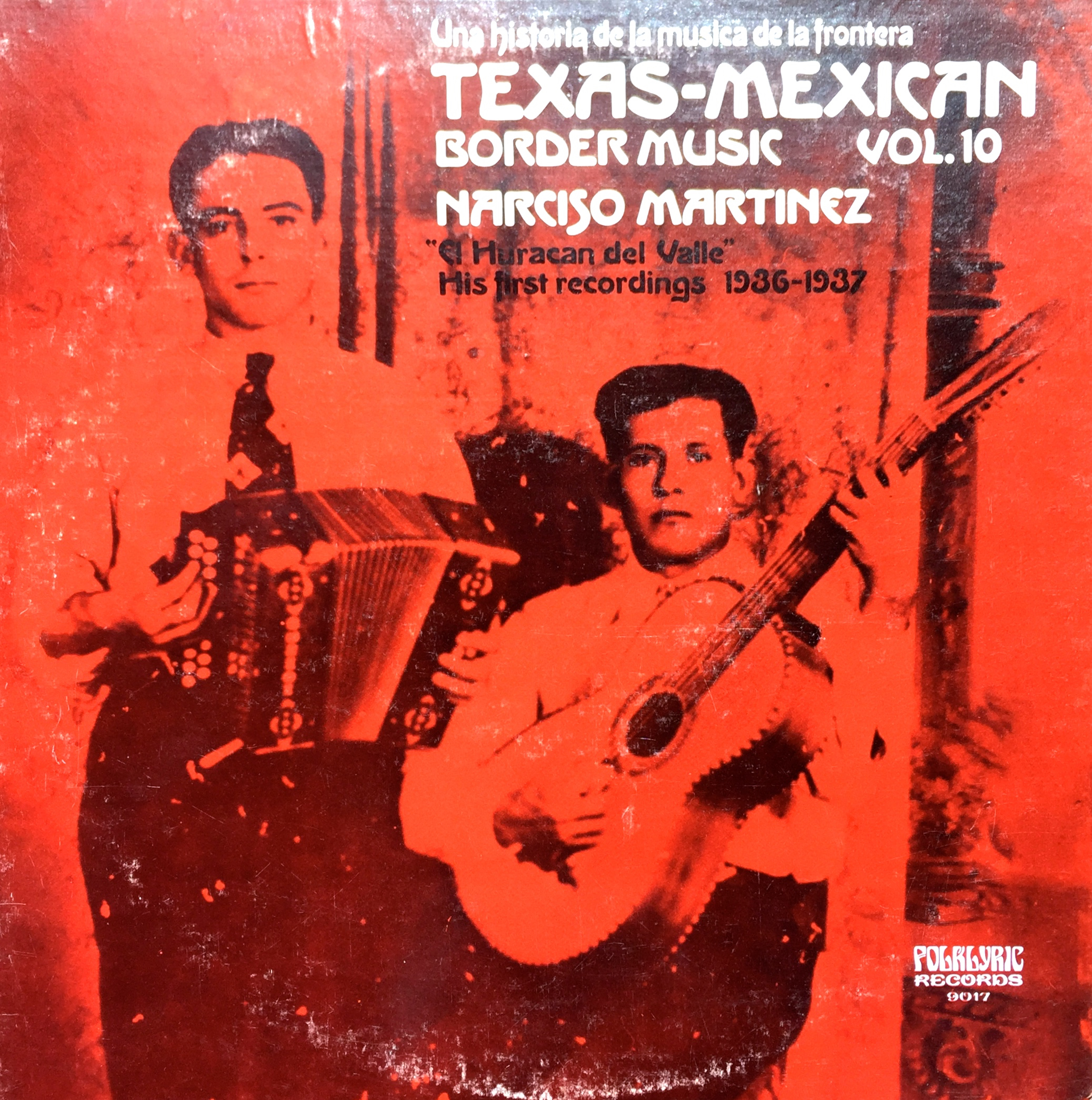

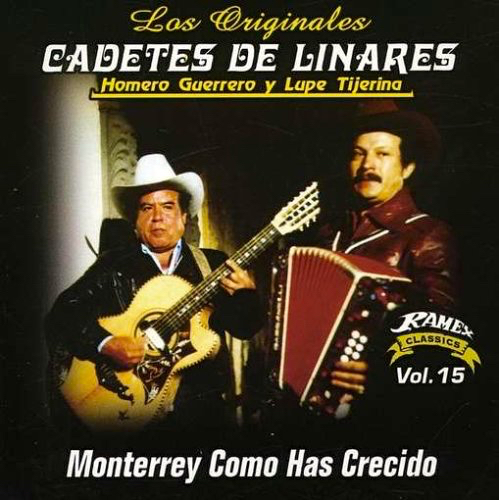

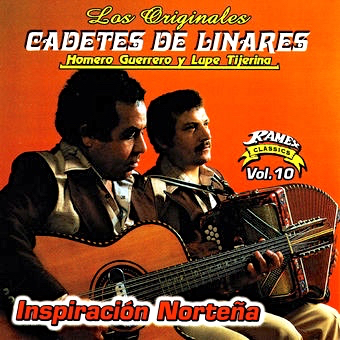

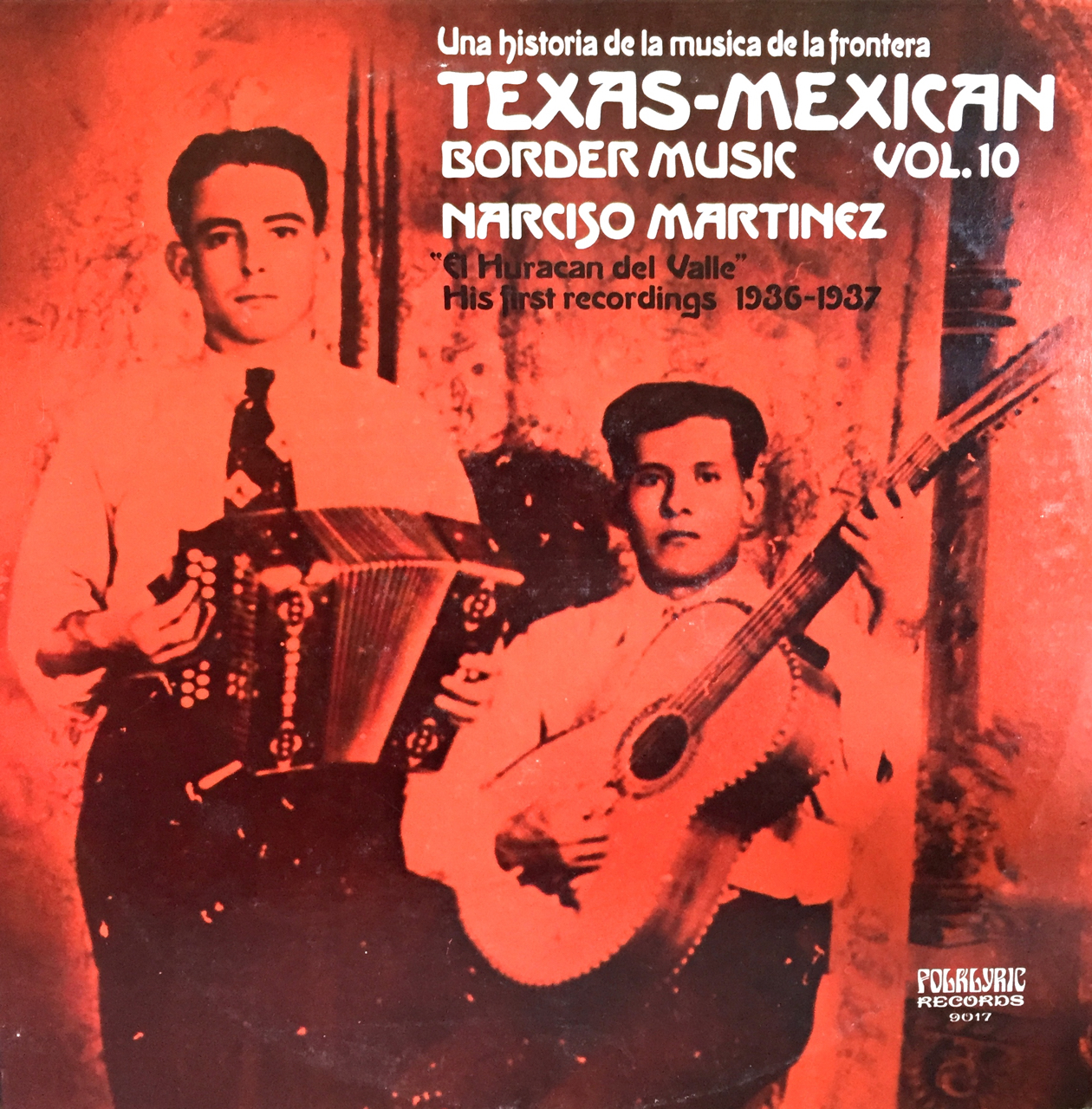

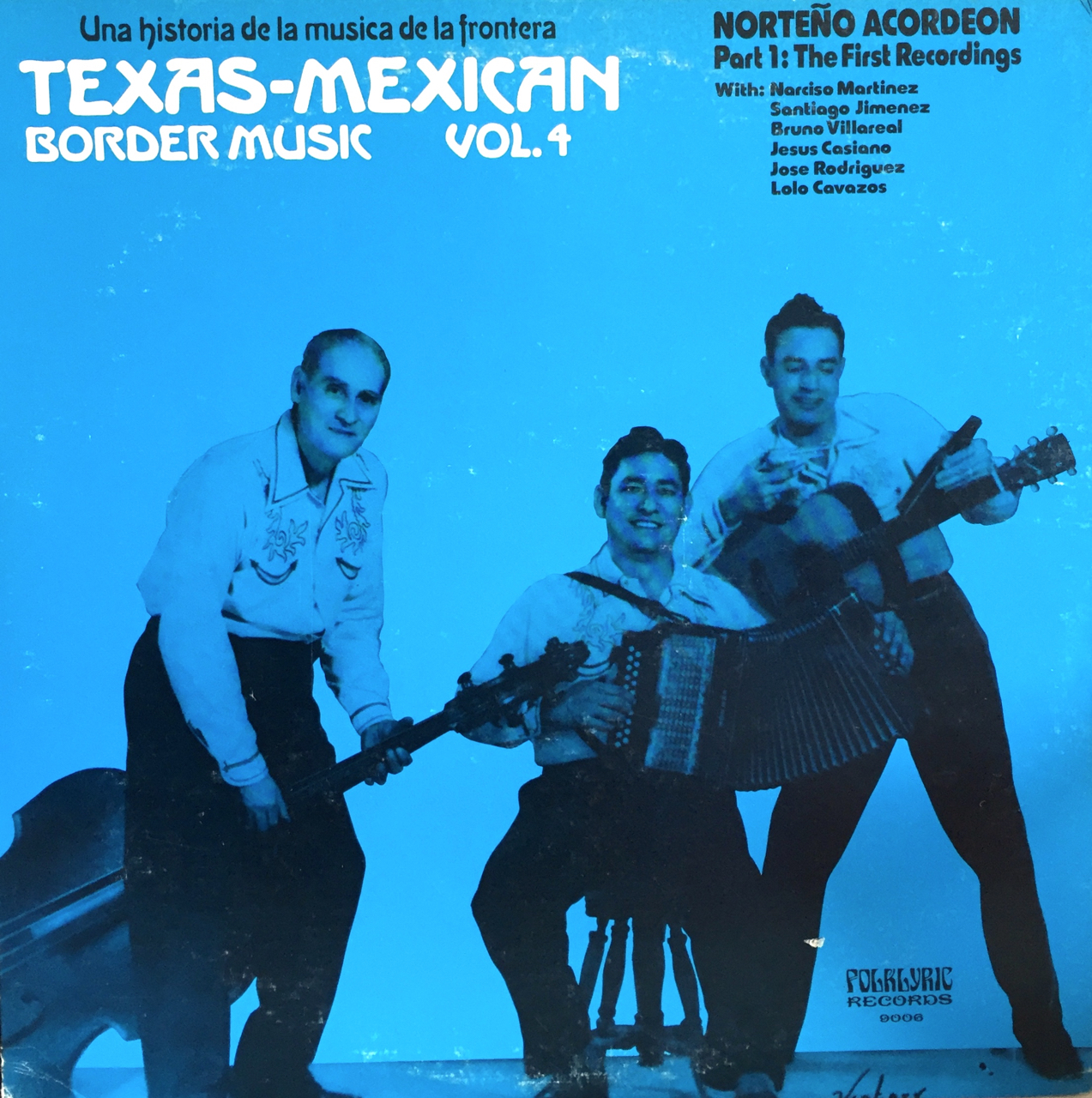

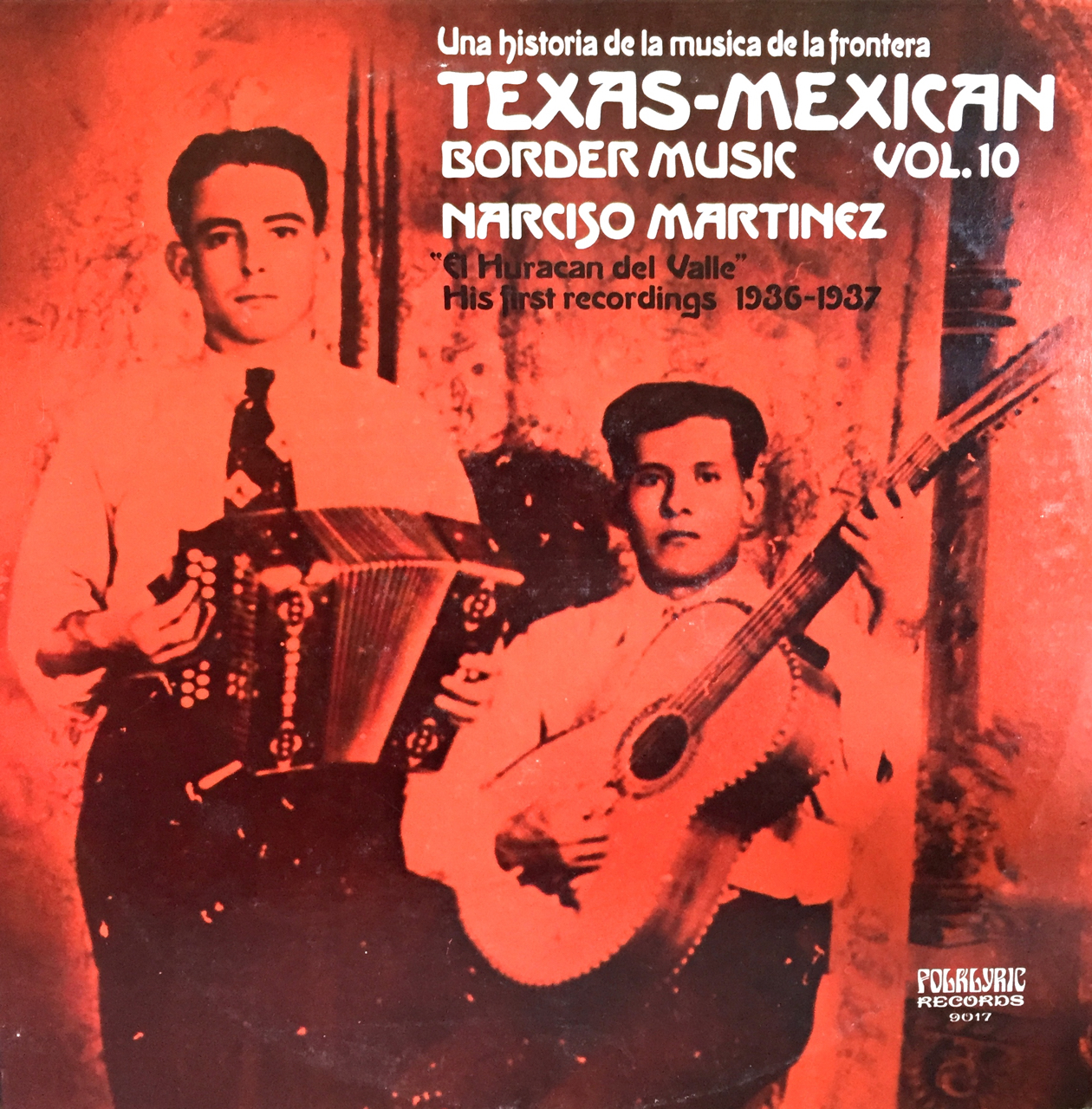

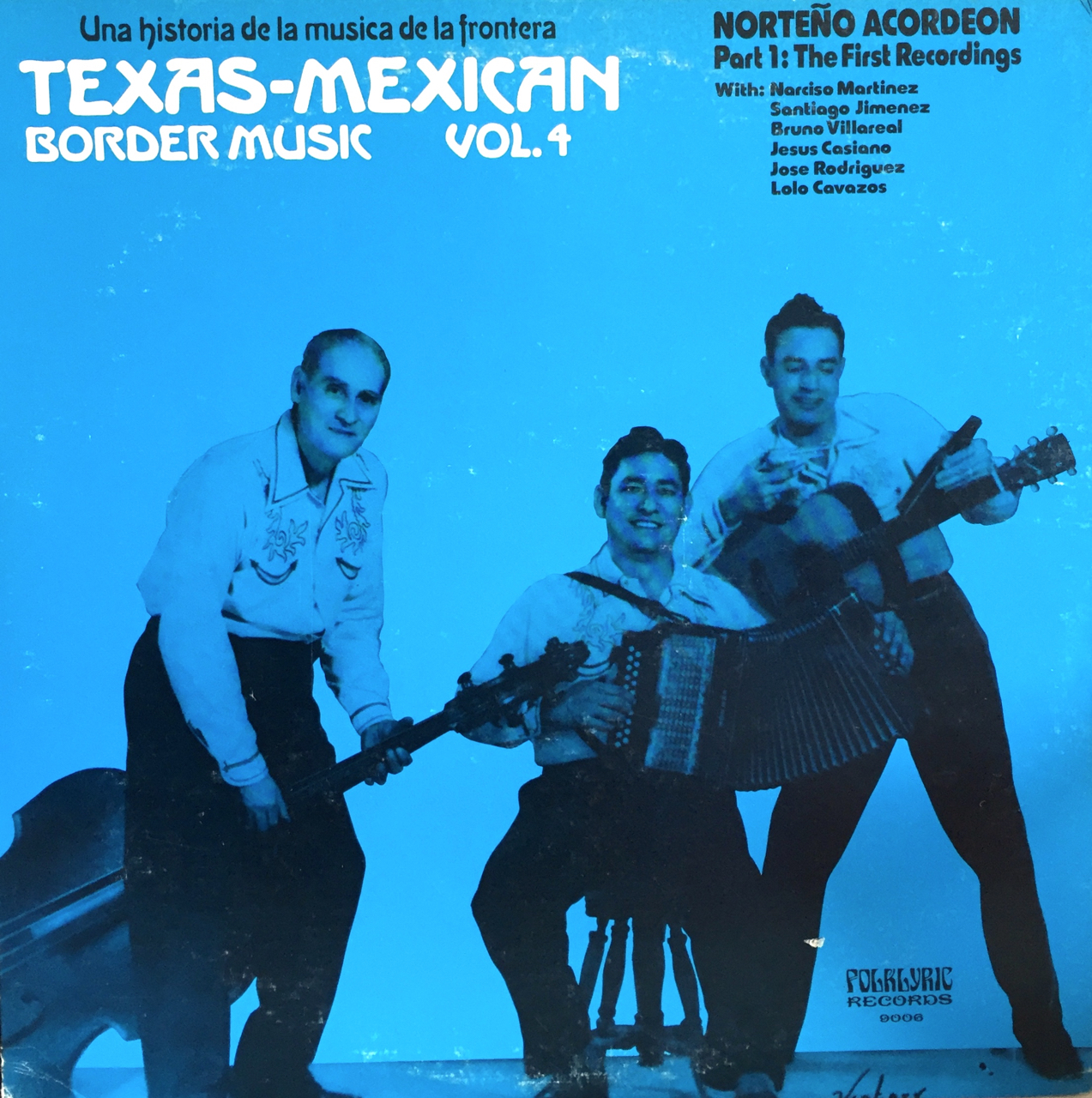

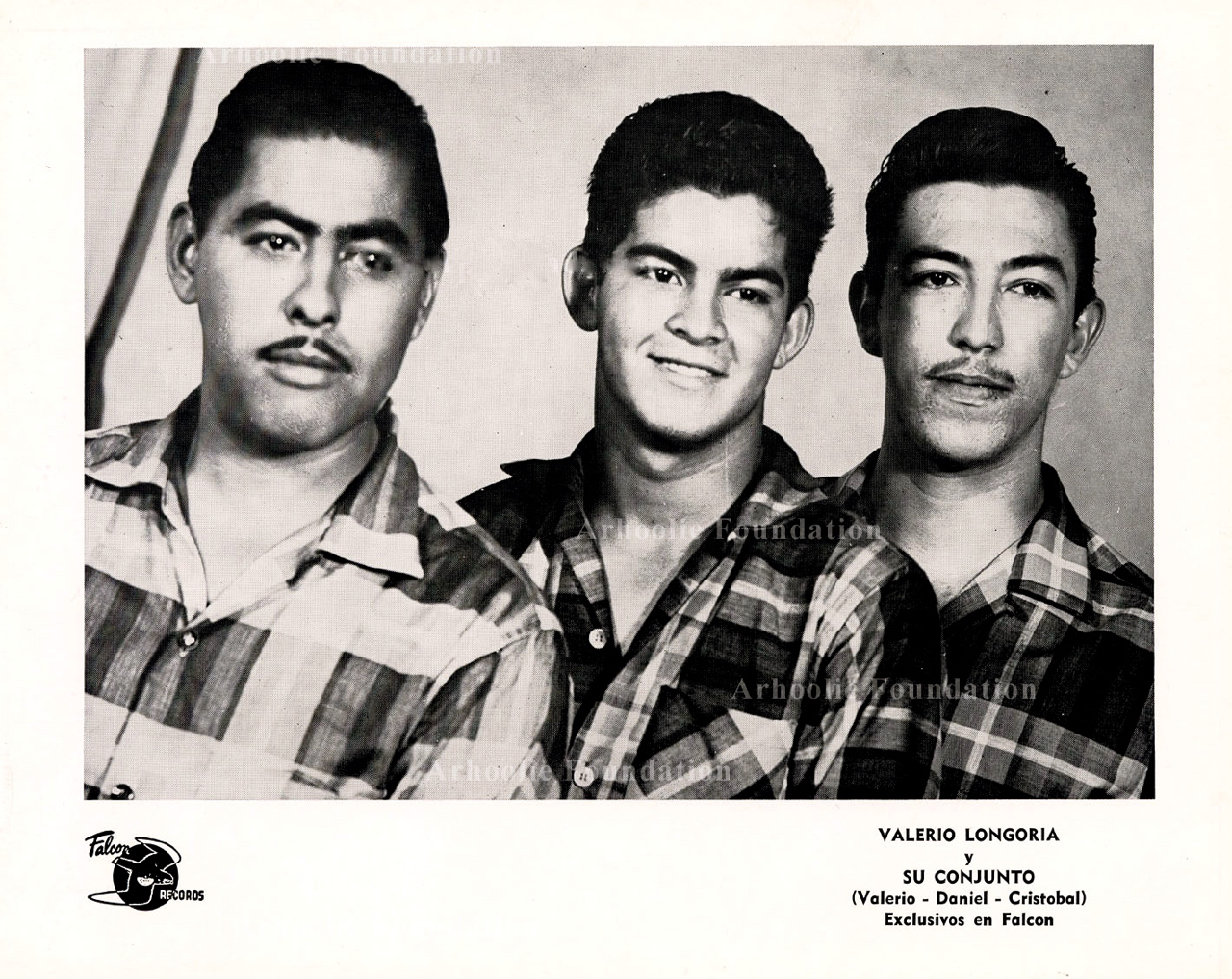

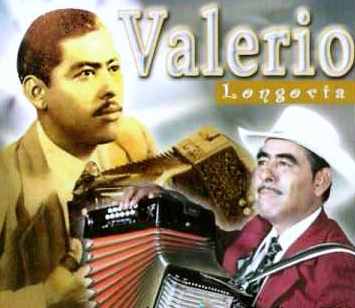

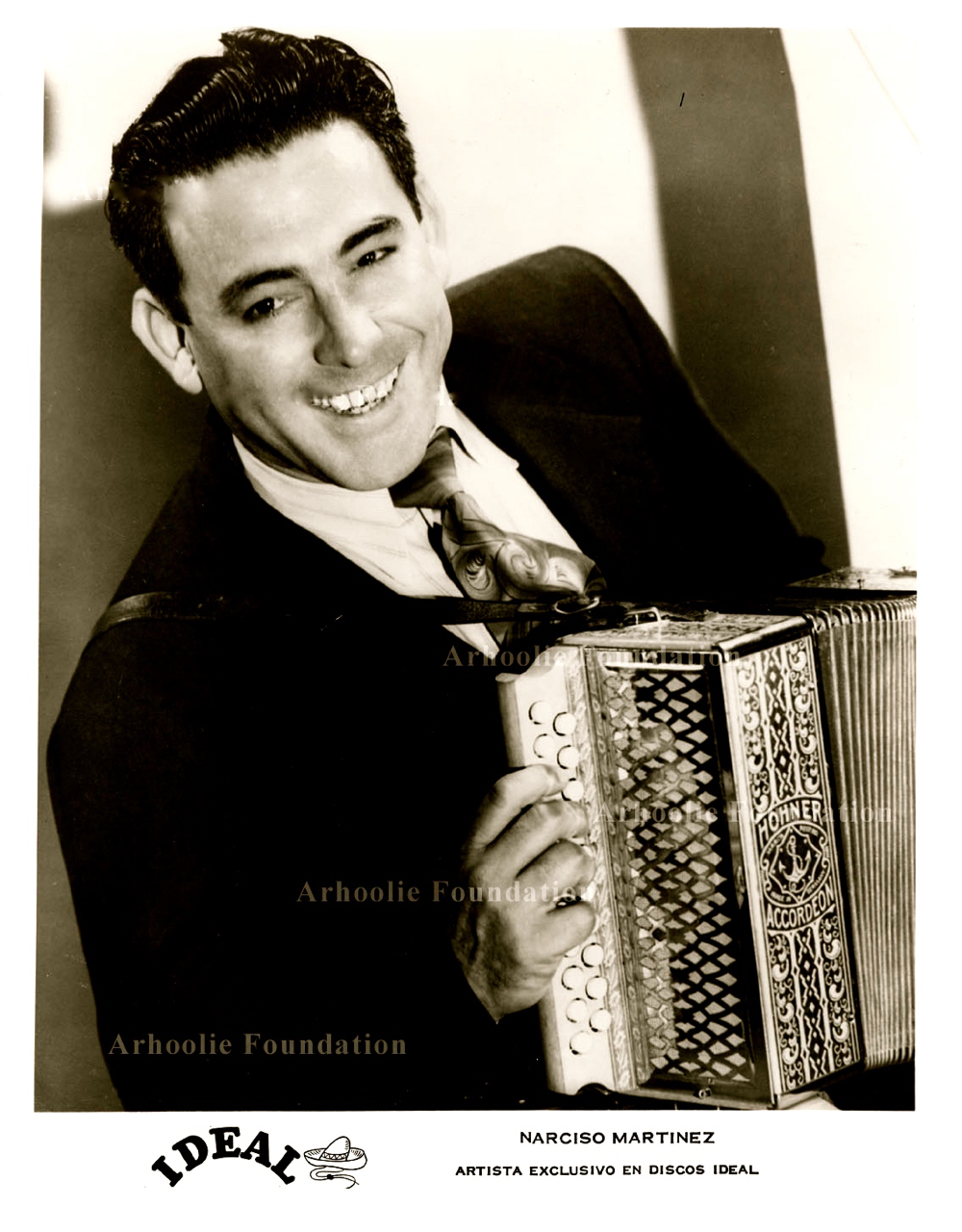

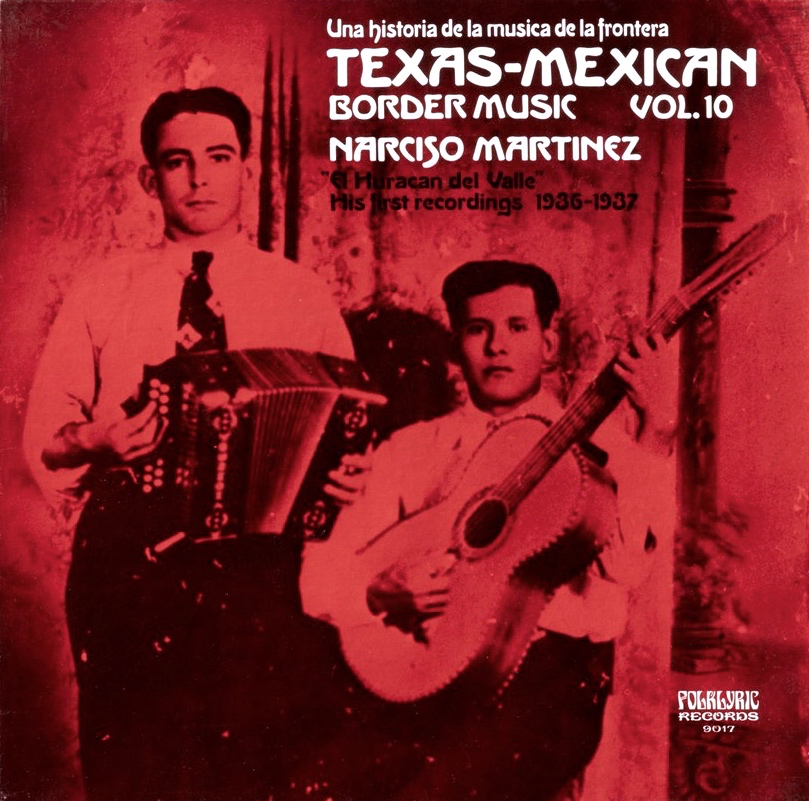

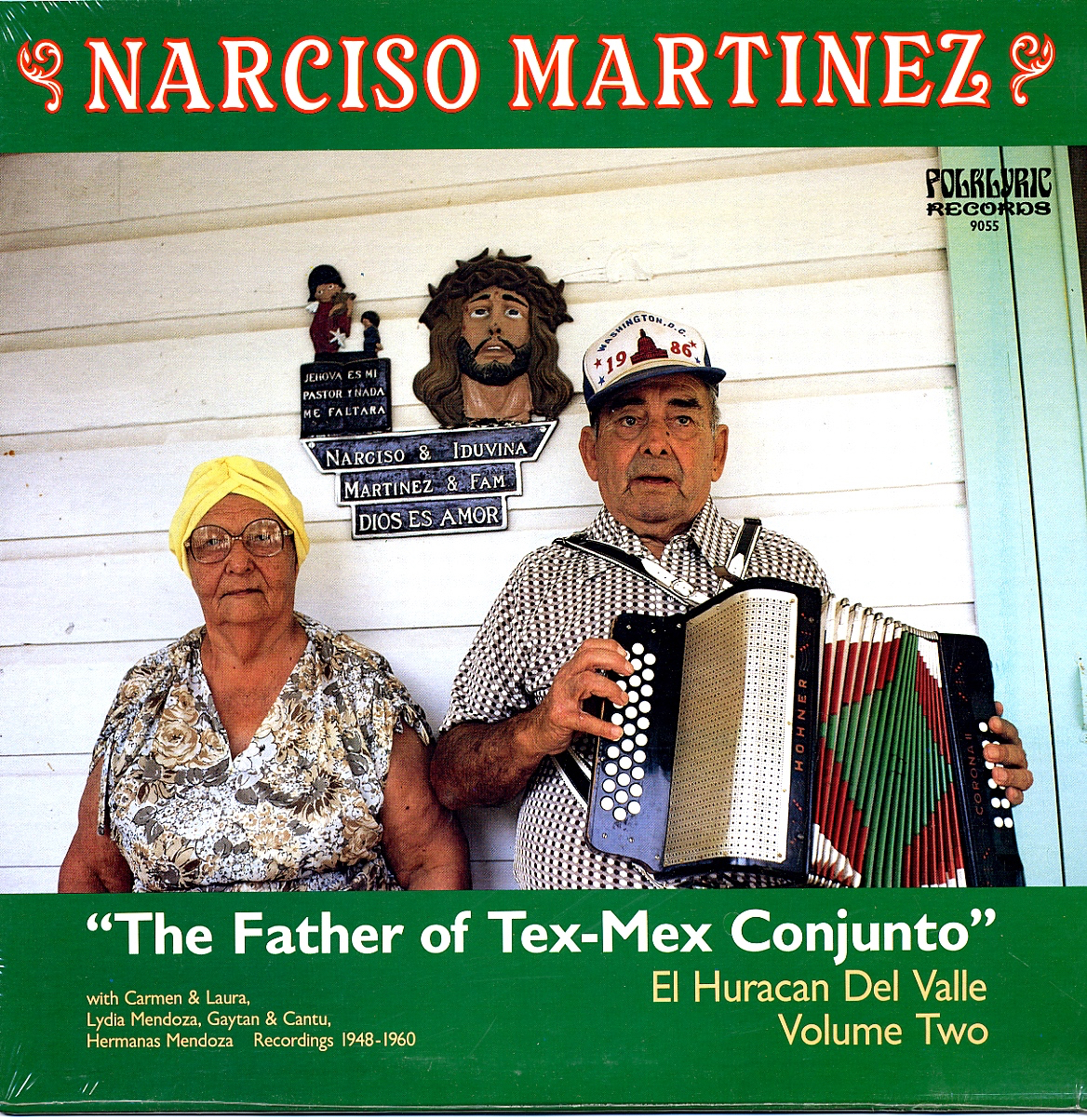

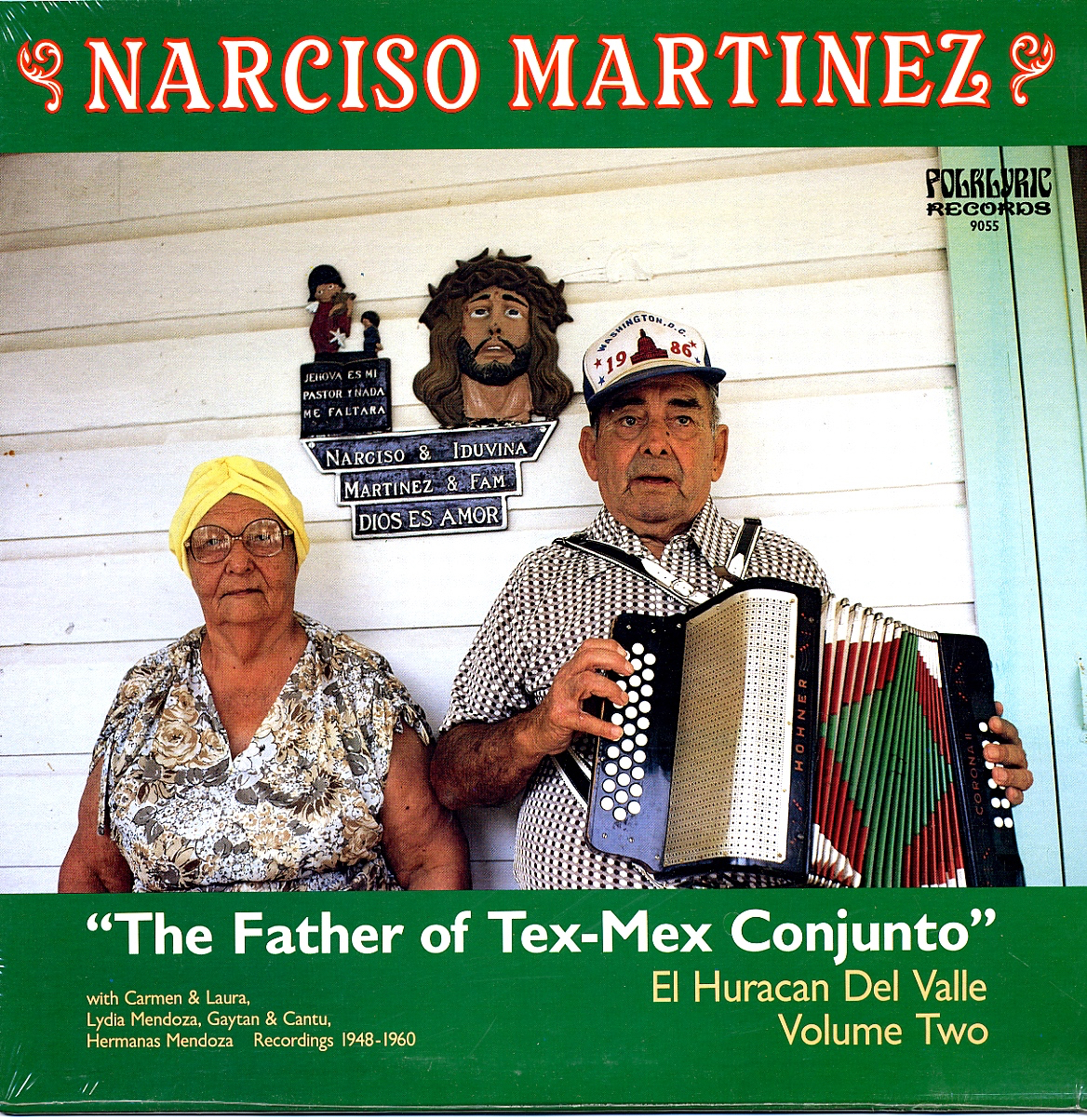

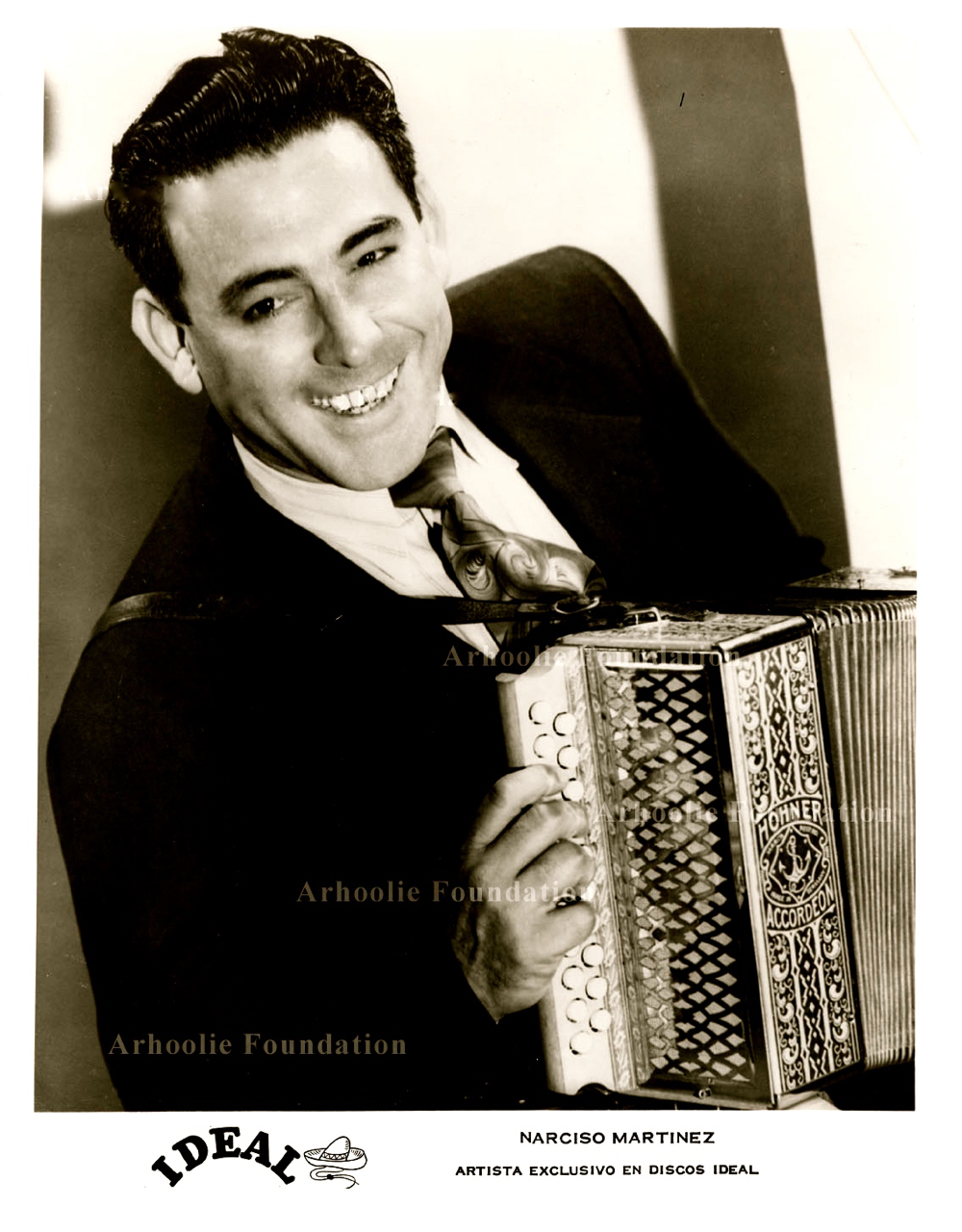

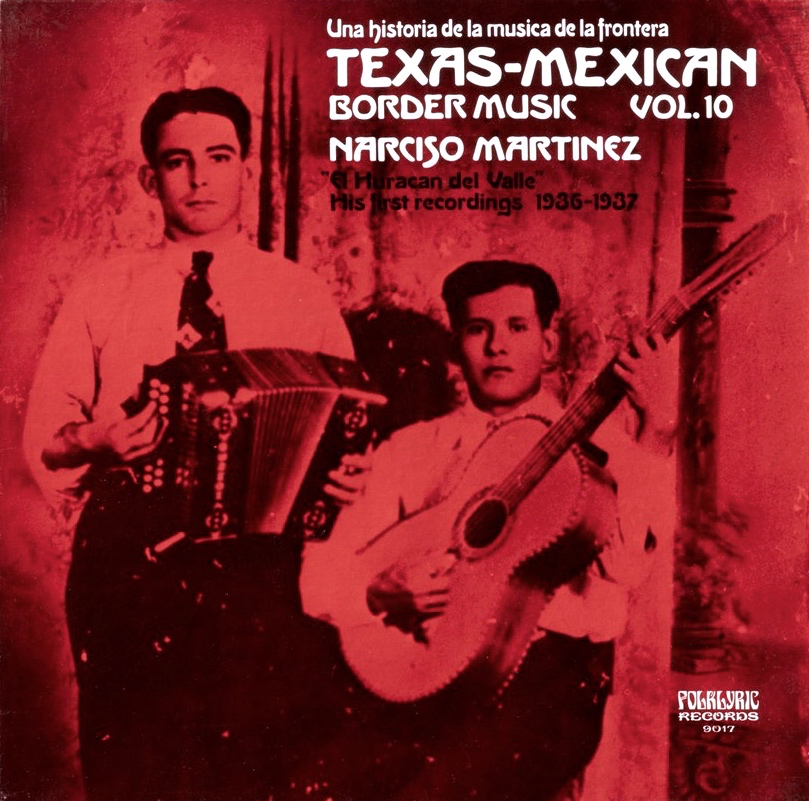

Zimmerle made a splash from the start. He broke with conjunto tradition, which typically called for a lineup of at least four musicians, choosing the trio format instead. Zimmerle admired the great Tejano accordionists who preceded him, such as Narciso Martinez and Santiago Jimenez, but by the late 1940s he had developed his own unique style on the squeezebox. On vocals, he incorporated the distinctive harmonies of duets popular in northern Mexico, thus minting the “Norteño Sound” within the conjunto genre of San Antonio.

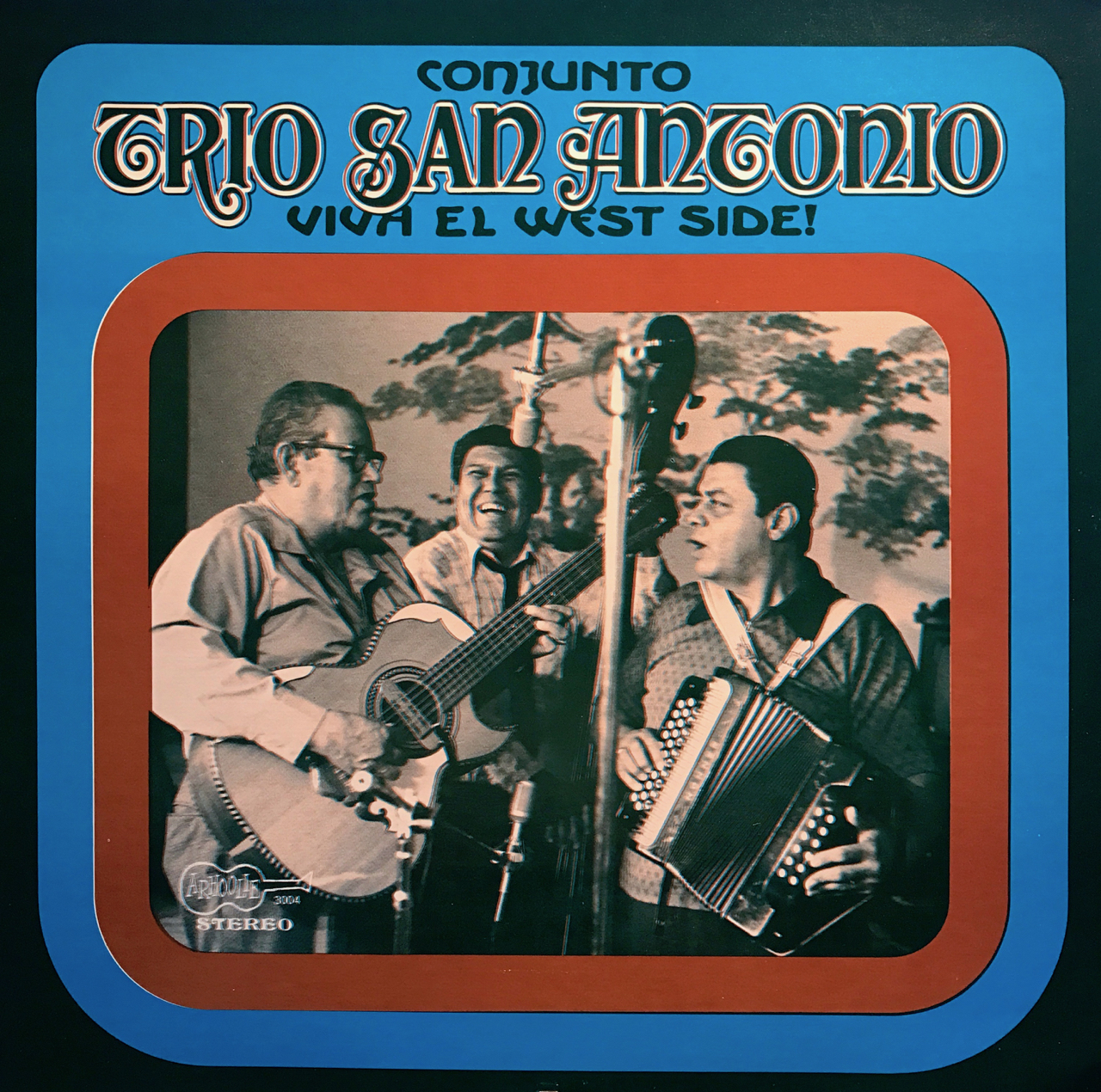

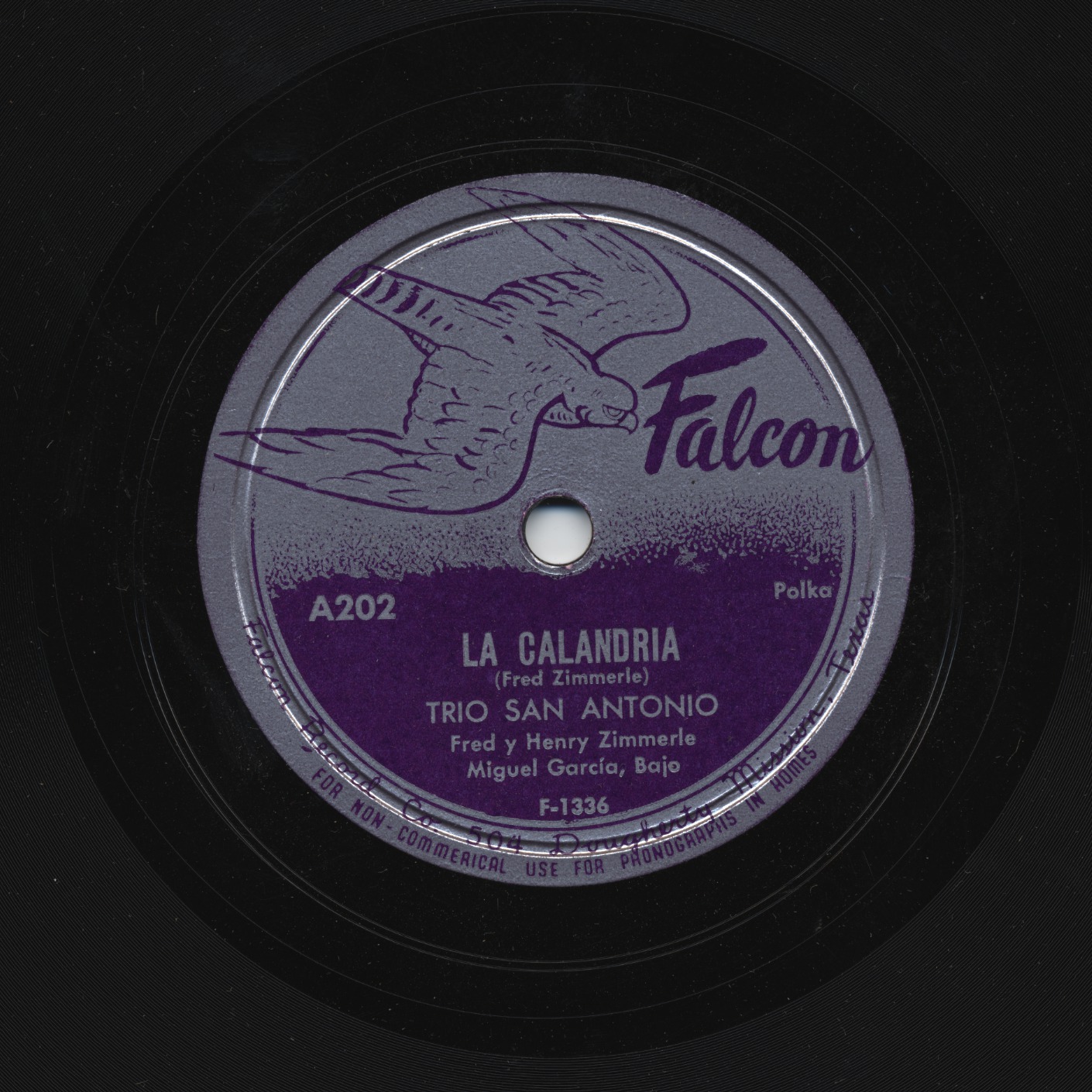

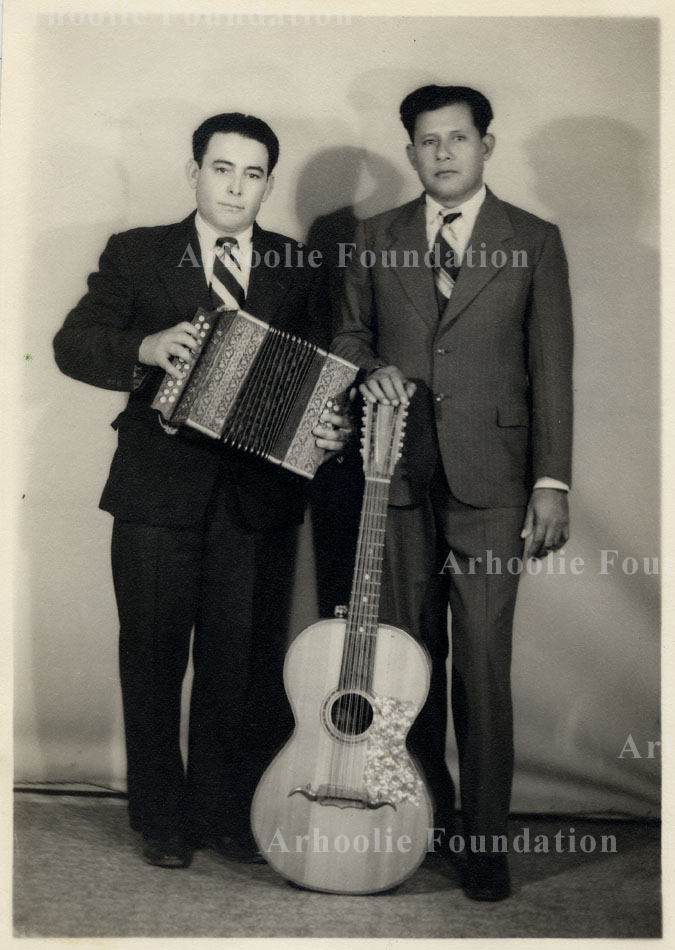

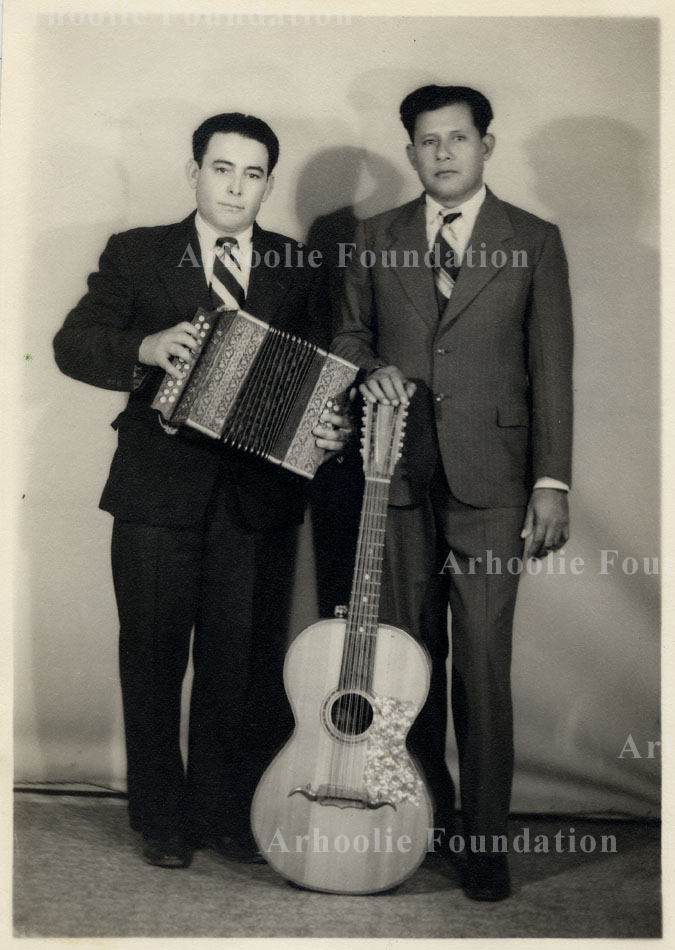

With the Trio San Antonio, Fred Zimmerle sang and played accordion. His vocal partners included brothers Henry, who was also a songwriter, and Santiago, who played bajo sexto. Other illustrious collaborators were Andrés Berlanga, Steve Jaramillo, and Martin Chavarria, all three of whom sang and played bajo sexto. The group also featured Juan Viesca who was known as “El Rey del Tololoche” and played the upright bass, or contrabajo, that was a cornerstone of post-war conjuntos through the late 1950s.

“Fred Zimmerle … has long been one of my favorite accordionists, and his duet singing with old-time troubadour Berlanga brings chills down my spine,” wrote Frontera Collection founder Chris Strachwitz in notes to a compilation. He cites one track in particular as an outstanding examp le of Zimmerle and Berlanga performing together with the early Trio San Antonio: “Un Recuerdo Quedó” (One Memory Remained), recorded in 1945 as a 78 on the Ideal label. “This selection has some of the purest country-style singing in Mexican-American music,” adds Strachwitz. (Aside from doing vocals on this track, Zimmerle plays accordion and Berlanga is on bajo sexto.)

le of Zimmerle and Berlanga performing together with the early Trio San Antonio: “Un Recuerdo Quedó” (One Memory Remained), recorded in 1945 as a 78 on the Ideal label. “This selection has some of the purest country-style singing in Mexican-American music,” adds Strachwitz. (Aside from doing vocals on this track, Zimmerle plays accordion and Berlanga is on bajo sexto.)

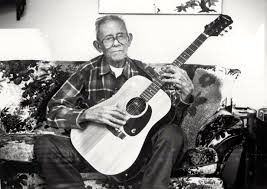

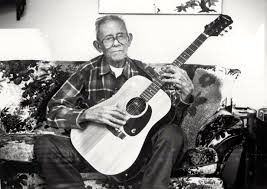

Like many other artists in this working-class genre, Zimmerle held a day job to support his musical career. Until his retirement, he worked days at the Kelly Air Force Base in San Antonio. In his later years, he taught accordion classes at the Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center in San Antonio.

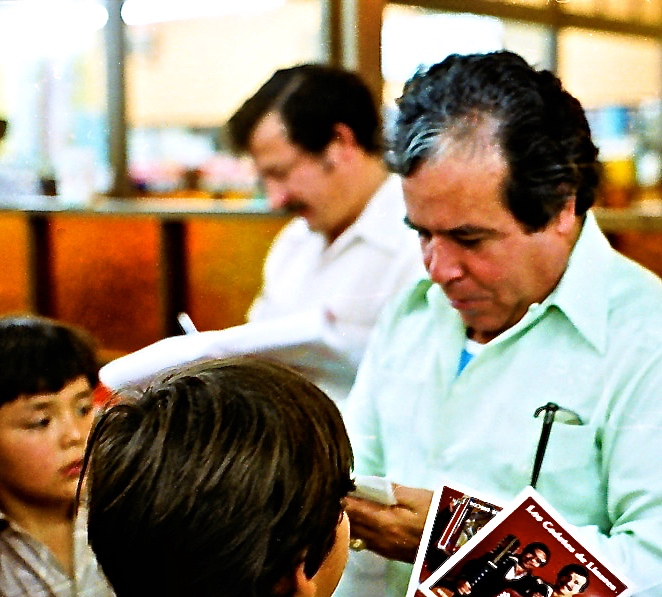

“Younger musicians would often pay a pilgrimage to Zimmerle's door to meet him,” writes AllMusic.com biographer Eugene Chadbourne. “German punk rock group FSK paid such a visit, and remarked in a later tour-diary that they were surprised that [Zimmerle] didn't know a single word of the Deutsche mother tongue. They must not have realized that although Zimmerle's grandfather was German, he was 100 percent Tex-Mex.”

The Frontera Collection contains dozens of recordings by both Trio San Antonio and Fred Zimmerle as a solo artist. Many of these recordings have been released over the years by Arhoolie Records as compilations , including the eponymous LP (Arhoolie 3004) featuring the catchy polka “Viva el West Side” that  highlights the group’s musicianship. (The album was later reissued on CD (Arhoolie 9052) with additional tracks.) Thanks to Strachwitz’s liner notes, these albums also serve as the primary source on Zimmerle’s life and career. Despite his stature in the genre, whatever written material about the artist that may exist is not readily found online.

highlights the group’s musicianship. (The album was later reissued on CD (Arhoolie 9052) with additional tracks.) Thanks to Strachwitz’s liner notes, these albums also serve as the primary source on Zimmerle’s life and career. Despite his stature in the genre, whatever written material about the artist that may exist is not readily found online.

In 1978, Zimmerle was the subject of an oral history conducted by journalist Allan Turner, who specialized in the folk culture of Texas and the South. Turner’s tapes of his interviews with Zimmerle, along with musical recordings, are preserved in the Allan Turner Collection, part of the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History at the University of Texas, Austin.

Trio San Antonio remained relatively active until Zimmerle's death from a heart attack on March 5, 1998.

– Agustín Gurza

Blog Category

Tags

Images

Conjunto music, the accordion style so popular with Mexican Americans throughout the Southwest, comprises a cornerstone of the Frontera Collection. Yet conjunto as such does not appear on the list of Top 20 genres compiled for my

Conjunto music, the accordion style so popular with Mexican Americans throughout the Southwest, comprises a cornerstone of the Frontera Collection. Yet conjunto as such does not appear on the list of Top 20 genres compiled for my