The Eternal Bolero, Part 3: Staying Alive

The bolero may not be what it used to be, but as they say in show business, it had a great run. Plus, a great revival or two.

Like most popular music styles, the bolero had its heyday before fading from the commercial mainstream. It enjoyed a sustained period of success that spanned a third of the 20th century, from the 1930s to the 1960s. But its popularity waned in the wake of new musical trends.

The bolero suffered a significant slump in the 1980s, a decade of major shifts in Latin music. Rock en Español was surging throughout Spain and Latin America. Traditional Mexican music, which often featured boleros rancheros, was starting to lose ground to the controversial narco-corrido and the loud and brassy banda style from Mexico’s Pacific coast. Meanwhile, along the Atlantic coast of the United States, racy reggaeton sounds from Puerto Rico and Panama attracted a new generation with profane lyrics and dirty dancing that left little room for the poetic tenderness and old-fashioned romanticism of traditional, genteel love songs.

As the end of the millennium drew near, the lyrical bolero seemed like a thing of the past.

Yet, the bolero is not a passing fad, like disco or La Macarena, nor a style stuck in history, like ragtime or the French contredanse. It is very much a living, evolving song style, refreshed by new composers and young generations of fans.

As a song style, the bolero is more comparable to the music of the classic American Songbook, with songs closely connected to truly iconic composers such as Cole Porter, Irving Berlin, and stellar songwriting teams such as George and Ira Gershwin and Rodgers and Hammerstein. No matter how many celebrity crooners interpreted their tunes (Sinatra, Bennett, Fitzgerald), the songs were always branded by the songwriters.

Similarly, boleros are tied less to their various interpreters than to their famed composers, ones who are considered cornerstones of Latin American culture, not just creators of a song style. To say the names Agustin Lara or Cesar Portillo de la Luz is to evoke an era, a worldview, a way of life. These beloved songwriters and their music will never fall from favor, or from the collective memory.

The longevity of the genre was confirmed by the bolero renaissance that emerged unexpectedly during the 1990s. The revival was fueled by two separate nostalgia trends that opened and closed the decade like bookends. These twin revivals took root in the two countries that had served as twin fountainheads of the genre: Mexico and Cuba.

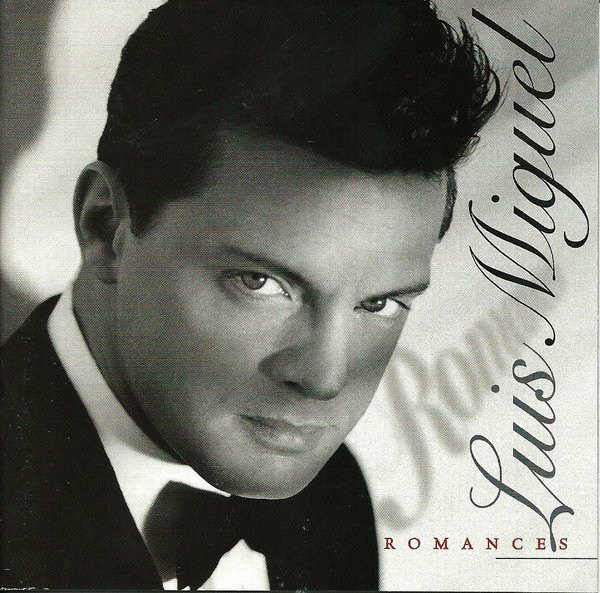

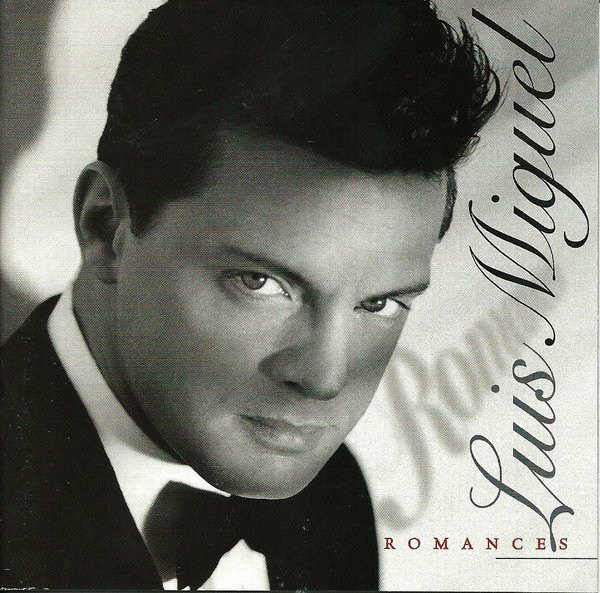

In 1991, as I have mentioned, Luis Miguel sparked a bolero craze in Mexico with the first album in his Romances trilogy, a series of recordings offering his modern take on classic songs from the genre, dressed up with new orchestral arrangements. Taken as a whole, the crooner’s series served as a survey of the Spanish-speaking world’s most enduring love songs. (Coincidentally, his recordings include many songs I highlighted as personal favorites in Part 1 and Part 2. Perhaps that is to be expected; bolero fans share affinity for the same beloved tunes of the repertoire.)

Six years later, in 1997, American guitarist Ry Cooder visited Cuba and helped launch Buena Vista Social Club, the internationally renowned ensemble of old-guard artists, who incited a nostalgia craze of their own for traditional Cuban music around the world. The albums by Buena Vista and its offshoot solo stars – Omara Portuondo, Ibrahim Ferrer, Compay Segundo – did not concentrate on boleros. But since they focused on music from the genre’s golden era in Cuba, the recordings featured several boleros sprinkled throughout, introducing non-Latin audiences to these classic old songs for the first time.

In this final installment of my bolero blog series, I am featuring boleros that re-emerged during the ‘90s revival. These songs could have easily figured in the first two installments, since they are also tunes I learned during my childhood and young adulthood. But blogs have limits, while the list of good boleros seems endless.

In this final installment of my bolero blog series, I am featuring boleros that re-emerged during the ‘90s revival. These songs could have easily figured in the first two installments, since they are also tunes I learned during my childhood and young adulthood. But blogs have limits, while the list of good boleros seems endless.

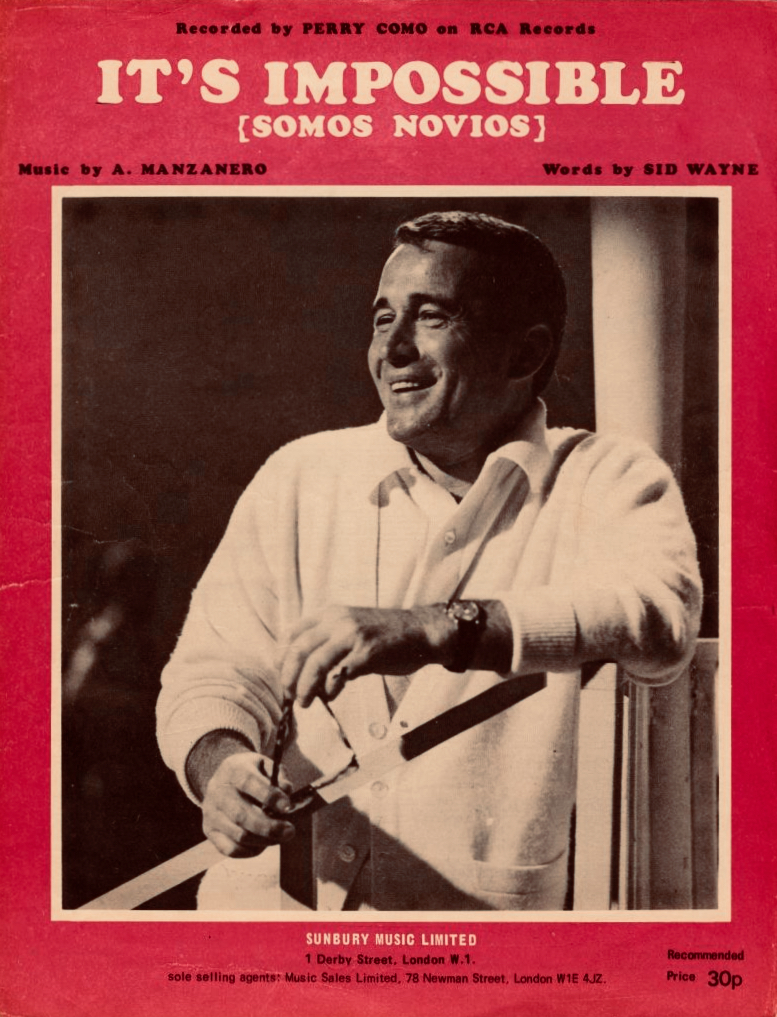

I would be remiss, however, to wind up an extended review of the genre without mentioning Armando Manzanero, one of Mexico’s top songwriters from the last half of the 20th century. With captivating compositions during the 1970s and 1980s, the native of Yucatan provided a bridge between the era of the historic bolero and the renaissance at the end of the century. It is not by accident that he wound up co-producing Luis Miguel’s smash revival LPs.

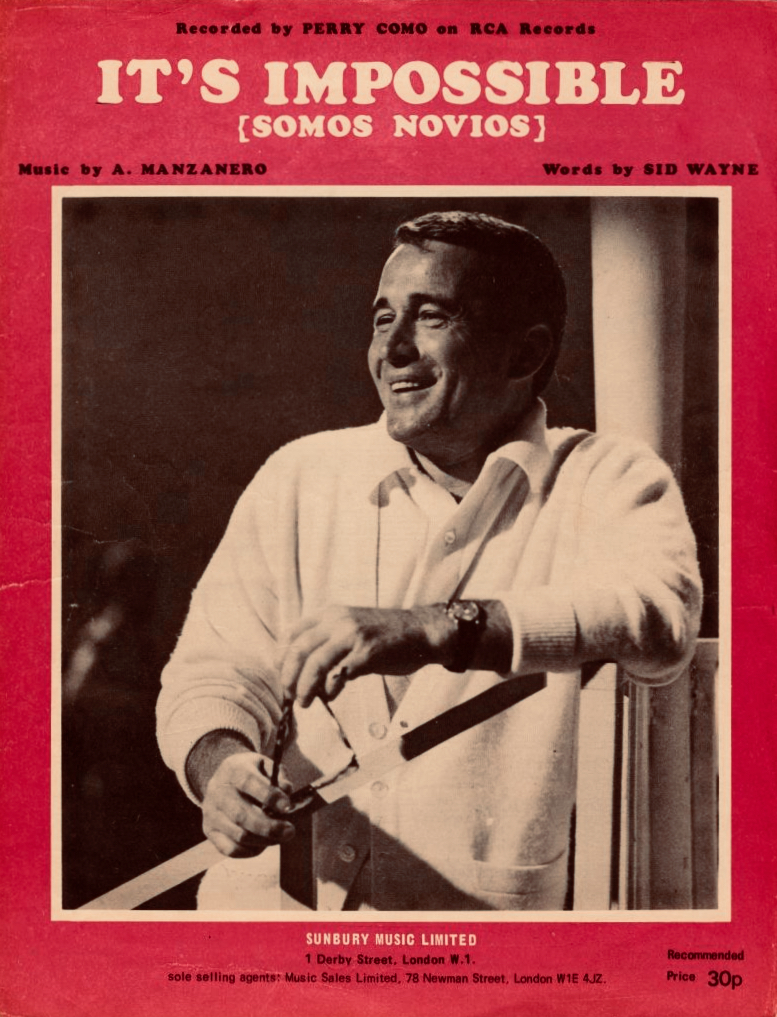

At our wedding in 2002, my wife and I played one of Manzanero’s biggest hits, “Somos Novios,” which he had written and recorded in 1968. The songwriter himself plays piano on this concert performance by Luis Miguel.

Most U.S. fans will recognize the tune from its English translation, “It’s Impossible,” with new lyrics written in 1970 by Sid Wayne. That same year, the translated tune was first recorded by Perry Como, who turned it into his first Top Ten hit in more than 12 years.

“It’s Impossible” remains one of the most covered Spanish-language songs of all time, with versions by artists as varied as Johnny Mathis (1971), Elvis Presley (1973), Vic Damone (1997), Julio Iglesias (2006), Andrea Bocelli (2006) and Engelbert Humperdinck in duet with Manzanero (2014), not to mention nearly four dozen instrumental renditions by artists such as Mantovani (1971), Los Indios Tabajaras (1971), and The Ventures (1979).

During his career, Manzanero wrote more than 400 songs, including the hits “Esta Tarde Vi Llover,” “Contigo Aprendí,” and “Adoro,” which are also among my favorites.

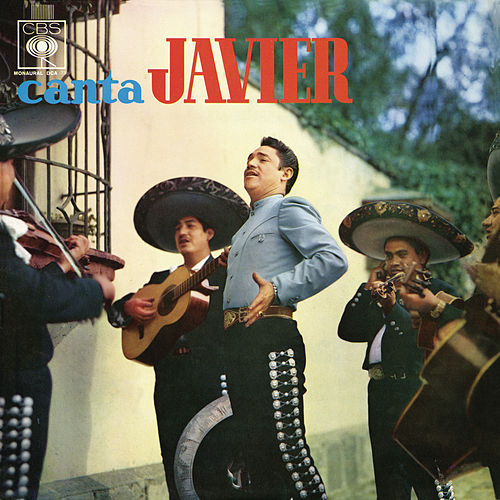

The celebrated singer/songwriter died on Dec. 28, 2020 at age 83. Almost a year later, on Dec. 12, 2021, Mexico lost another towering musical figure, Vicente Fernandez, who indelibly defined música ranchera in the last half of the 20th century. Nicknamed “El Rey” and “El Ídolo de Mexico,” Fernandez was a master of the bolero ranchero, with a voice that could fluctuate between operatic power and whispered vulnerability.

English-language obituaries usually mentioned Fernandez’s signature hits, such as “El Rey” and “Volver, Volver.” But he recorded many memorable boleros that captured the agonizing depths of yearning and loss, as well as the tender passions, intrinsic to the genre. As a fan for the past 50 years, a few of my favorite Chente boleros include “Acá Entre Nos,” “A Pesar de Todo,” “Por Tu Maldito Amor,” “Que de Raro Tiene,” “Mujeres Divinas,” “De Qué Manera Te Olvido,” “Hermoso Cariño,”and many, many more.

At this stage of my life as an inveterate music fan, there aren’t many famous boleros I’m not familiar with. However, the Nostalgic Nineties reminded me of a few that I love and are worthy of note in this final installment. In keeping with the concept of a recap, I’ve also created a playlist on Spotify of my Top 40 boleros, including the ones I featured in this series and a few more gems from my library of cherished love songs.

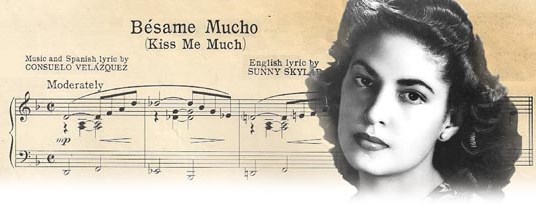

“Bésame Mucho” by Consuelo Velasquez & Daniel Riolobos

“Bésame Mucho” by Consuelo Velasquez & Daniel Riolobos

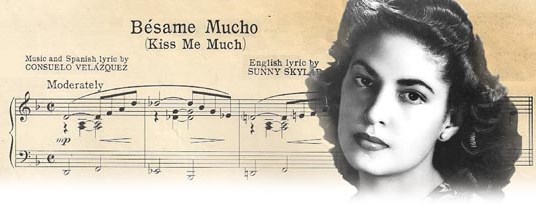

Reporter Morley Safer of 60 Minutes once said on the air that this was the worst song ever written. I guess no woman ever desired his kisses so much, which is mucho. Maybe Safer missed the meaning, and the feeling, in translation. “Kiss Me a Lot” doesn’t cut it, because it’s not the number of kisses that matters, but rather the sustained, intense passion of kisses that blend into one. The song is a classic, written by one of the few women in the pantheon of bolero composers, Consuelo Velázquez of Mexico. She manages to blend passionate desire and the dread of separation in her lyrics.

After her death in 2005 at age 88, The New York Times hailed her most famous song. “‘Bésame Mucho’ is not so much an enduring standard as a global phenomenon,” the obituary stated. “Translated into dozens of languages and performed by hundreds of artists, the song has been an emblem of Latin identity, an anthem of lovers separated by World War II and perennial grist for lounge singers everywhere.”

Velázquez also wrote the song’s alluring melody that effectively enhances the emotion, as evidenced by the many instrumental versions of the tune, including this jazzy take by Dave Brubeck. It is one of the most widely covered songs in Latin music, with versions by Josephine Baker, Charro, the Coasters, Nat King Cole, Xavier Cugat, Plácido Domingo, Bill Evans, Connie Francis, Harry James, Diana Krall, Trini Lopez, Dean Martin, Art Pepper, the Platters, Tito Puente, and (famously) The Beatles. In the unusual performance linked above, the songwriter plays piano to accompany Argentinean singer Daniel Riolobos, who walks on stage and, surprisingly, starts singing the song in the middle, with the bridge that foreshadows the couple’s separation.

Quiero tenerte muy cerca,

Mirarme en tus ojos,

Verte junto a mi.

Piensa que tal vez mañana

Yo ya estaré lejos,

Muy lejos de aquí

“Historia de Un Amor” by Luis Miguel

The young crooner does a marvelous job with this oft-recorded bolero of heartbreak and loss. It’s one of those standards that is taken for granted, with lyrics that can apply to any relationship suffering a separation. However, most fans are not aware of the real-life heartbreak behind the song.

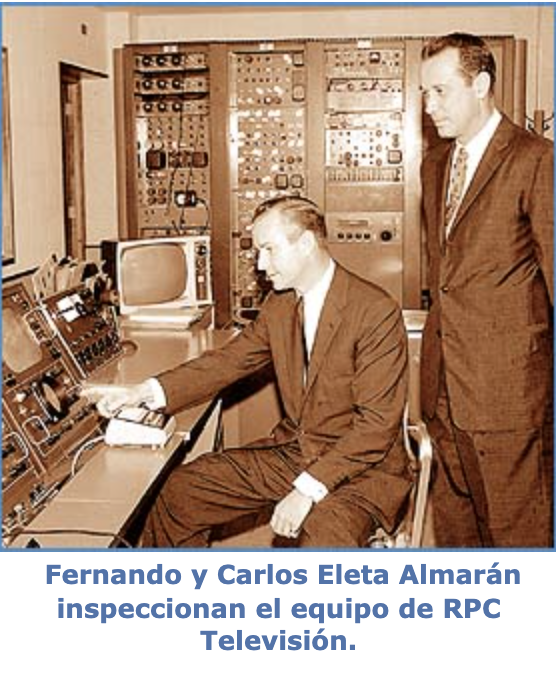

It was written in 1955 by Carlos Eleta Almarán, perhaps the only Panamanian songwriters to reach that top echelon of boleristas with this tune. He wrote it as a sorrowful farewell following the untimely death of his sister-in-law, Mercedes, wife of his brother Fernando. She died of polio in 1954, after only four years of marriage and leaving behind three children.

Almarán’s lyrics take on deeper significance in light of the tragic circumstances of its origins. The permanence of the loss is underscored by the swelling melody that comes to a crescendo, then denouement, as the words lament that the light of love has been extinguished forever by an eternal absence.

Almarán’s lyrics take on deeper significance in light of the tragic circumstances of its origins. The permanence of the loss is underscored by the swelling melody that comes to a crescendo, then denouement, as the words lament that the light of love has been extinguished forever by an eternal absence.

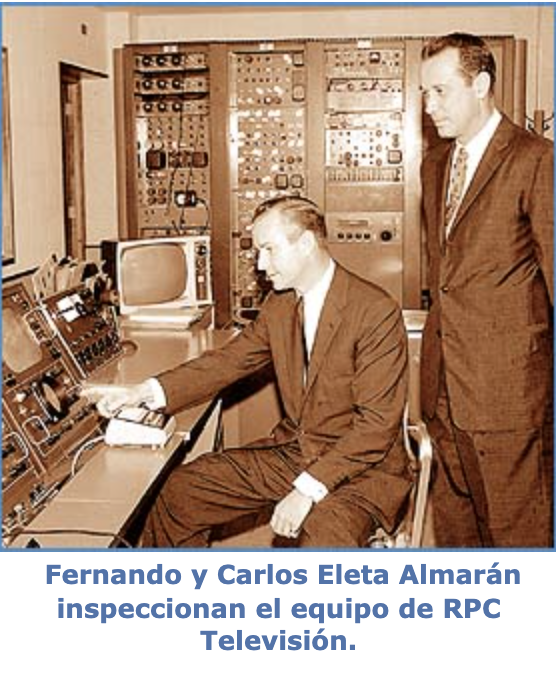

Almarán (whose songwriting credits use his maternal surname rather than Eleta, his father’s name) was also a successful entrepreneur. In 1960, he founded, along with his brother, Panama’s first, and now its oldest, television station, RPC TV. Fernando, who held degrees from Stanford and MIT, went on to remarry and served in top government posts.

Meanwhile, the song that bound them in trauma went on to worldwide success. It was first recorded in 1955 by Libertatd Lamarque, featured in the Mexican film of the same name. The following year, it was refashioned as a tango by Lamarque’s fellow Argentinean Hector Varela and his orquesta típica.

In the intervening 66 years, the song has been covered by a constellation of stars: Guadalupe Pineda, Marco Antonio Solís, David Bisbal, Lola Flores, Marco Antonio Muñiz, Pedro Infante, Ana Gabriel, Eydie Gormé & Trio Los Panchos, Julio Iglesias, Perez Prado, Pedro Infante, Cesaria Evora, Eartha Kitt, Il Divo, and Diego El Cigala.

Additionally, it was translated into several languages, including Chinese, English, Hungarian, Romanian, Finnish, and French.

La Mentira (Se Te Olvida) by Luis Miguel

This bolero, “The Lie,” was written by Álvaro Carrillo (1921 – 1969), one of Mexico’s most prolific songwriters. The composer has penned more than 300 songs, including what ranks perhaps as the most popular bolero of all time, “Sabor a Mí,” which I featured in my post “Romance and Revolution in ‘Sabor a Mí.’”

“Veinte Años” by Buena Vista Social Club

This sad song entered the canon of Cuban boleros almost from the time of its 1935 debut, with its sorrowful lyrics by Guillermina Aramburu and melancholy melody by composer Maria Teresa Vera (1895-1965). The song, however, is almost always credited to Vera alone, for reasons most people, including myself, have been unaware of until recently. Apparently, Aramburu wrote the verses after the collapse of her marriage of 20 years, hence the title. According to the Madrid-based music website Radio Gladys Palmera, the lyricist gave the lyrics to Vera, her friend since childhood, on the condition she not reveal who wrote it.

Technically classified as an habanera, the song was originally performed with simple guitar accompaniment, in the style of traditional Cuban trova. Vera made an early recording of the tune with her partner at the time, Lorenzo Hierrezuelo, a duet formed in the mid-1930s, around the same time the song was written. Their collaboration lasted a quarter of a century. During that time, Hierrezuelo also formed half of another famous duo, Los Compadres; in which he sang lead vocals and was nicknamed Compay Primo, while his partner, Francisco Repilado, handled harmonies, or second voice, and was thus known as Compay Segundo, who emerged decades later as prominent member of Buena Vista Social Club.

“Veinte Años” appears on scores of recordings, especially from Cuba. I have almost three dozen versions in my private collection. Among my favorites is the exceptional rendition by Bebo & Cigala, the Spanish/Cuban duo composed of Bebo Valdes and flamenco singer Diego El Cigala. Another, more traditional version was recorded in 1964 by Cuban folk singer Celeste Mendoza. She’s backed by the popular Havana-based son revival group, Sierra Maestra, led by Juan de Marcos Gonzalez, a key creative force in the creation of the Buena Vista band that extended and enhanced his mission of preserving the traditional son music of the Sierra Maestra mountain range.

And the story comes full circle.

The song was 60 years old when it was recorded for the inaugural Buena Vista album (1997), and later included on the solo, self-titled album (2000) by the ensemble’s beloved singer Omara Portuondo.

The song was 60 years old when it was recorded for the inaugural Buena Vista album (1997), and later included on the solo, self-titled album (2000) by the ensemble’s beloved singer Omara Portuondo.

But nothing quite matches the heart-melting charm of a recent version by a brother-sister duo known as Isaac et Nora, a couple of South Korean kids living in Brittany in northwest France. In their informal YouTube clip from 2019, the children shyly sing the Spanish lyrics, while Isaac plays a trumpet solo and their bespectacled father plays guitar in the background, flashing occasional approving smiles.

In an amazing development that could never have been foreseen by the bolerista generation, this video of “Veinte Años” has accumulated more than 7 million views. The brother-sister act has soared in global popularity. They have a new album of Latin standards, Latin & Love Studies, a polished, professional Facebook page with 1.4 million followers, and a YouTube channel that has attracted almost 57 million views.

And the bolero lives on.

– Agustín Gurza

Also in this series:

The Eternal Bolero, Part 1: Love Songs That Endure for Decades

The Eternal Bolero, Part 2: Songs I Learned in College

Blog Category

Tags

Images