Artist Biography: Rita Vidaurri, Treasure of San Antonio

Until her recent death, singer Rita Vidaurri (1924–2019) stood as the last surviving star of what is considered a Golden Age of female vocalists from San Antonio, during the 1930s and ’40s. Like her contemporaries Eva Garza (1917-1966), Rosita Fernandez (1919-2006), and Lydia Mendoza (1916-2007), Vidaurri relied on the Alamo City’s vibrant Mexican-American music scene to launch an international career, sharing world stages with superstars such as Nat “King” Cole, Pedro Infante, and Celia Cruz.

Until her recent death, singer Rita Vidaurri (1924–2019) stood as the last surviving star of what is considered a Golden Age of female vocalists from San Antonio, during the 1930s and ’40s. Like her contemporaries Eva Garza (1917-1966), Rosita Fernandez (1919-2006), and Lydia Mendoza (1916-2007), Vidaurri relied on the Alamo City’s vibrant Mexican-American music scene to launch an international career, sharing world stages with superstars such as Nat “King” Cole, Pedro Infante, and Celia Cruz.

After a lengthy interruption to raise her four children, Vidaurri resumed performing at the start of the new millennium, enjoying a sensational comeback that capped a career spanning eight decades. The veteran vocalist died in her hometown on January 16 of this year. She was 94.

On stage, Vidaurri projected a self-assured persona, bantering with the audience, making wisecracks, and telling slightly bawdy jokes. Yet, her professional exterior masked a life of hardship and struggle. She fought to overcome shyness as a child and machismo throughout her life. Most tragically, she endured the death of three grown sons and suffered bouts of depression and illness over the years.

Yet, Vidaurri never stopped singing.

“Performing was always the best medicine for Rita,” says Tejano music historian and collector Ramón Hernández. “She ranks with the all-time greats and still hasn’t received all the recognition she deserves.”

Early Years in San Antonio

Rita Vidaurri Castillo was born May 24, 1924, in a humble home on Montezuma Street in San Antonio’s West Side barrio, one of the poorest neighborhoods in the country. She was named for a 15th century Italian saint, Rita of Cascia, known as Patroness of Impossible Causes, and protector of abused, heartbroken women.

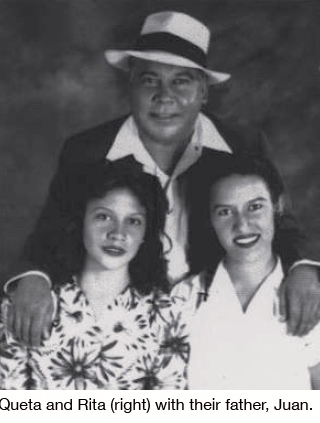

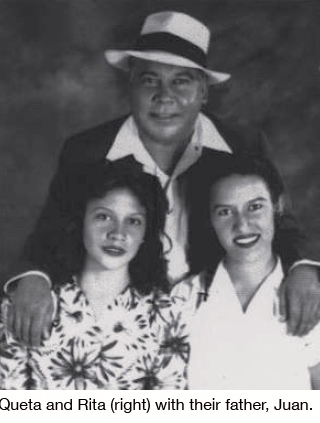

Her father, Juan Vidaurri, was born in the town of Musquiz, Coahuila, not far from the Mexican border with Texas. As a boy, he came to the United States with his family, joining a wave of migrants trying to escape the turmoil of the Mexican Revolution of 1910.

Having settled in Texas by the early 1920s, Juan Vidaurri met and married Maria de Jesus “Jesusita” Castillo, a San Antonio native. Jesusita was just 16 when Rita, the first of her three children, was born; her husband was 19.

The elder Vidaurri was a mechanic who did auto repairs in the back of his home. He also owned and operated small barrio businesses—a gas station, a boxing ring, and a cantina. In his later years, he became known for his civic activism, turning his home into an ad hoc community center and political headquarters. Nicknamed “El Viejito,” he became well connected in Texas state political circles, and in 1977, San Antonio named a neighborhood park in his honor.

Initially, Juan Vidaurri did not approve of his daughter’s flirtation with show business. It was her mother who nurtured young Rita’s musical talent.

The girl’s destiny in music was presaged by a local man who picked up trash and bottles in the neighborhood but who was also considered a fortune teller. The barrio character heard the girl singing when he’d pass the Vidaurri household, and he gave her mother sage advice.

“Let her sing if she wants to sing,” the man said. “She’s going to be something big.”

Jesusita, who worked as a house cleaner, took the prediction seriously. She arranged for a neighborhood boy to teach her daughter guitar at 50 cents a lesson. And behind her husband’s back, she started taking the girl downtown for the amateur talent competitions at the Teatro Nacional, a cultural hub of the city’s Mexican American community.

Rita, still in her pre-teen years, had to overcome her childhood shyness to perform. The aspiring vocalist tried to emulate popular singers from San Antonio, particularly Eva Garza and the renowned Lydia Mendoza, who had also competed in singing contests at the same venue.

The effort paid off. For 18 consecutive weeks, the young singer won first place in the amateur shows, taking home the five-dollar prize. Word of her success inevitably got back to her father, who “blew his top,” Rita once recalled.

One day, Mr. Vidaurri went to see for himself what all the fuss was about.

“My mother didn’t know that my father was in the audience,” Rita Vidaurri said in a 2010 interview with the magazine Latino USA. “But afterwards, when they placed the envelope over my head and said, ‘the winner,’ he liked hearing the audience applauding for me.”

Dad was not the only one who was impressed. Two top Mexican stars—comedian Cantinflas and composer Lorenzo Barcelata—also saw the girl perform at the San Antonio talent shows in the early 1940s, and would soon play separate roles in jump-starting her professional career. Meanwhile, Rita’s mother kept scouting local opportunities for her daughter to perform, often walking her to the various venues.

Before long, Rita was banned from the weekly talent shows she had come to dominate because organizers wanted to give other girls a chance to win. The young vocalist went on to find new audiences at the carpas—the vaudeville-style, travelling tent shows, such as Carpa García and La Carpa Cubana, that were popular among working-class Mexican Americans of that era. She also performed for workers at the hundreds of nuecerías, or pecan-shelling operations, that flourished in San Antonio during the Great Depression. Like a roving troubadour, the girl collected nickels and pennies in a can as she sang.

In addition, Rita kept winning competitions, including one sponsored by H&H Coffee, a local roaster. The prize paid $50, a Depression-era bonanza worth almost $900 today.

In the mid-1930s, Rita started performing with her younger sister, Enriqueta, touring small Texas towns as Las Hermanitas Vidaurri. It was a decade when female duets, such as Las Hermanas Padilla and Las Hermanas Mendoza (Lydia Mendoza’s sisters) had become widely popular.

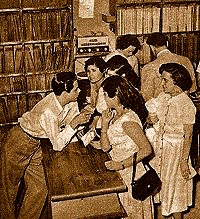

In 1938, Rita and Enriqueta Vidaurri made their first recording in a local furniture store, where records were commonly sold in those days. The session produced two tracks, “Alma Angelina” and “Atotonilco,” which, according to several accounts, were released on Bluebird Records, RCA’s respected budget label specializing in blues and jazz.

In 1938, Rita and Enriqueta Vidaurri made their first recording in a local furniture store, where records were commonly sold in those days. The session produced two tracks, “Alma Angelina” and “Atotonilco,” which, according to several accounts, were released on Bluebird Records, RCA’s respected budget label specializing in blues and jazz.

However, the Bluebird 78-rpm single in the Frontera Collection features only one of those songs, “Alma Angelina,” with a different song, “No Me Abandones,” on the flip side. The label bills the sisters as Rita y Queta, accompanied on the first song by orchestra, and by accordion and guitars on the other.

Their royalties came in the form of barter: The sisters were paid in furniture, for their mother.

Sadly, Jesusita Vidaurri did not live to witness her daughter’s ultimate success. She died of tuberculosis in 1939, at the age of 31. Rita was just 15 at the time, and the loss forced her to grow up quickly. As the oldest child, Rita assumed responsibility for the care of her sister and their brother, Juan.

“I was the one with the load to carry,” she said in a 2013 interview with journalist Hector Saldaña, published in the San Antonio News-Express on the occasion of her 89th birthday. “My mother made me promise to take care of them. My sister got married real young, and I was stuck with my father and my little brother.”

It was a big challenge for a teenager: working to help support the family while continuing her education and still pursuing performance opportunities. At various times, Rita picked cotton as a farmworker, helped as a mechanic in her father’s garage, and got a job as a weapons inspector in a military arsenal. She also worked at her father’s gas station and, in her desire to please him, found time to play softball and take up boxing. “He treated me like a boy,” she told the newspaper.

By now, however, Juan Vidaurri no longer objected to his daughter’s musical ambitions. In the early 1940s, Rita’s voice was on the radio in San Antonio, broadcast from the Teatro Nacional on La Hora Anahuac, a popular show sponsored by another local business, Davila Glass Works, and aired on English-language station KABC.

In 1942, the year Rita turned 18, she was among the first artists to perform at the new Guadalupe Theater, built on the site of her father’s gas station.

As she entered adulthood, Rita Vidaurri, the shy girl from the humble barrio, was on the verge of international stardom.

A Star Is Born

For a fledging singer from San Antonio in the mid-20th century, the quickest road to stardom went through Mexico. And in the Mexican music industry of that era, all roads led to the capital.

Rita Vidaurri’s first stop on her professional ascent was Monterrey, Nuevo Leon, a provincial capital that was emerging as a regional powerhouse for Mexican music.

The singer, accompanied by her now supportive father, performed on Monterrey’s popular radio station XEMR, and landed a gig at El Parthenon, one of the city’s top nightclubs where the emcee was Lalo Gonzalez, the comical norteño singer nicknamed El Piporro.

Vidaurri’s short, six-month stay in Monterrey had an immediate impact. Listeners were drawn to her commanding voice, described in her own words as “low but real loud.”

“The keys I sing in are the keys of the man,” she told the News-Express.

Vidaurri then took on her biggest career challenge: making her mark in Mexico City, the entertainment capital of Latin America at the time.

Cantinflas, one of Mexico’s biggest movie stars, became one of the young singer’s early advocates. In 1944, when she was 19, the comedian urged Juan Vidaurri to take his daughter to the Mexican capital to advance her career. The comedian personally signed a note of endorsement that helped the novice singer circumvent Mexican union requirements, allowing her to perform “and they wouldn’t bother me,” as Vidaurri explained in a 2011 interview for the PBS program, Conversations.

Lorenzo Barcelata, the famed actor, singer, and songwriter from Veracruz, became another early champion. The popular composer also carried clout, having shot to international fame with his most popular tune, “Maria Elena,” featured in the 1932 film Bordertown, starring Bette Davis. Barcelata’s other signature song, “El Cascabel,” was among the musical works launched into outer space on the Voyager Golden Record, as a sample of human creativity.

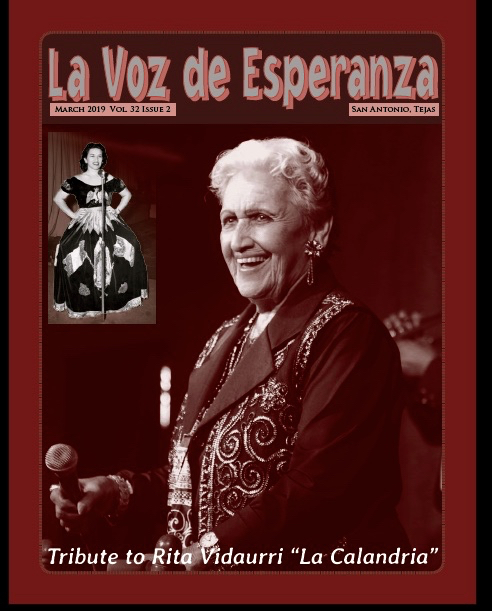

Barcelata gave Vidaurri his personal, autographed guitar, as well as her lifelong nickname, La Calandria (The Lark), according to a 2014 profile in La Voz de Esperanza, a monthly by the non-profit Esperanza Peace and Justice Center, which would help spark the singer’s late-life revival.

Once in Mexico City, Vidaurri’s career continued to get a boost from key show business figures.

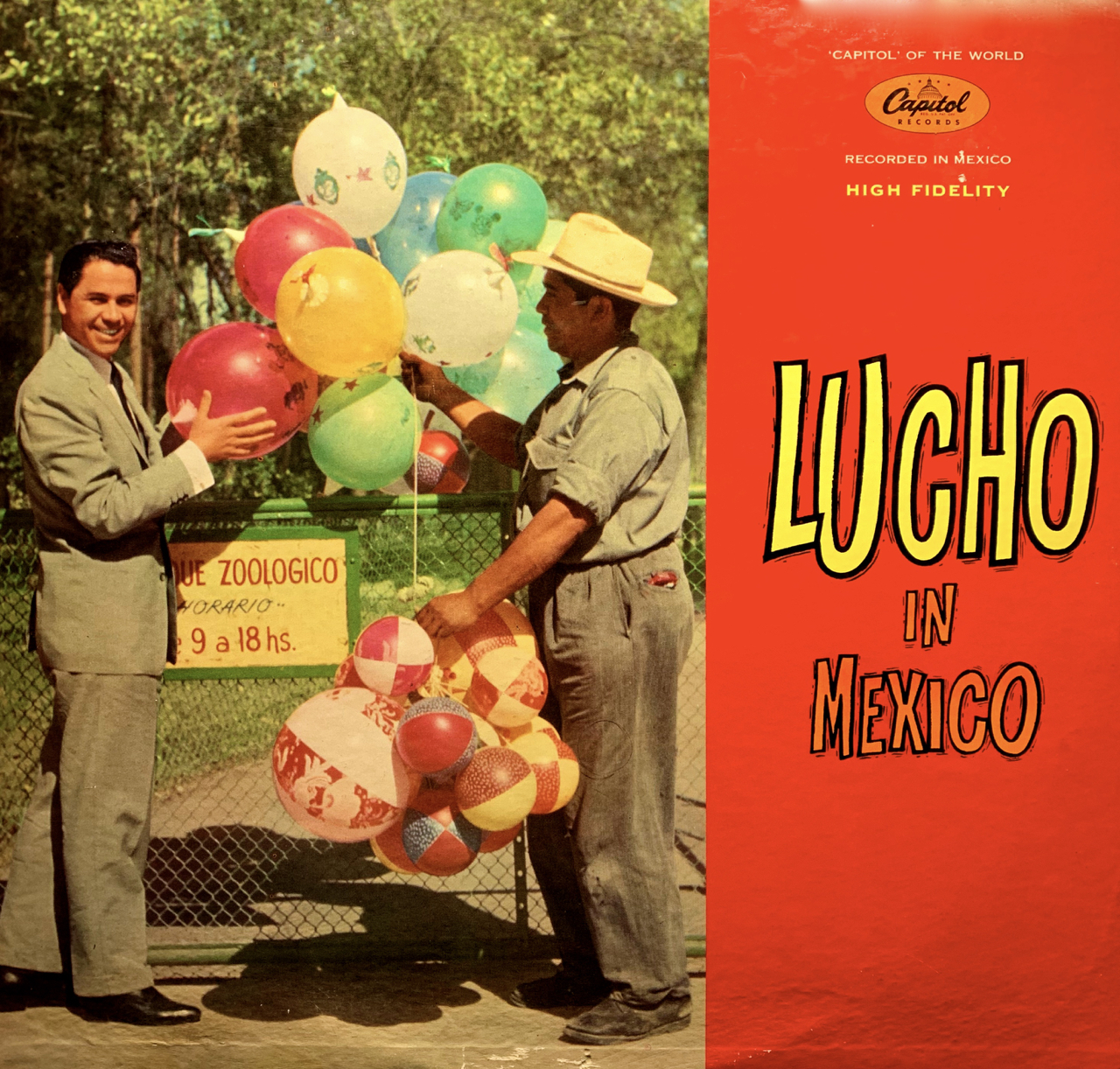

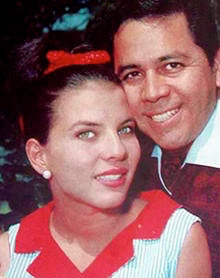

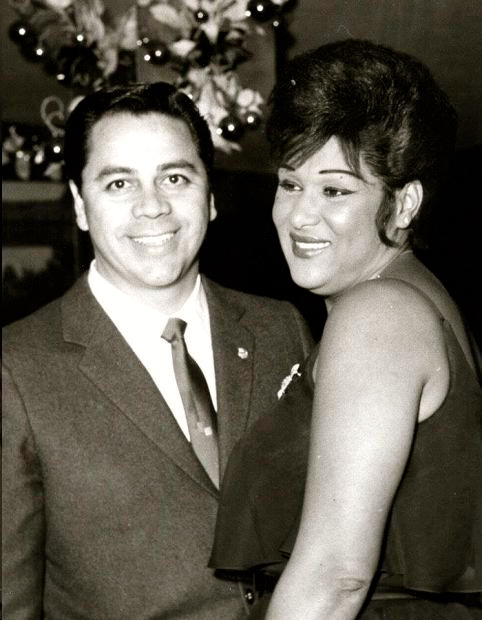

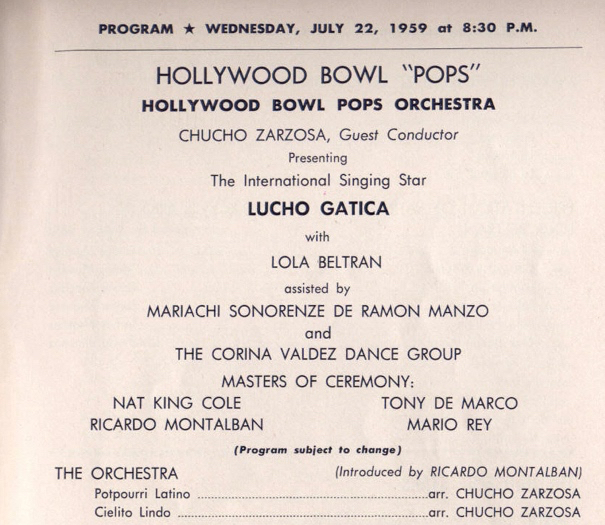

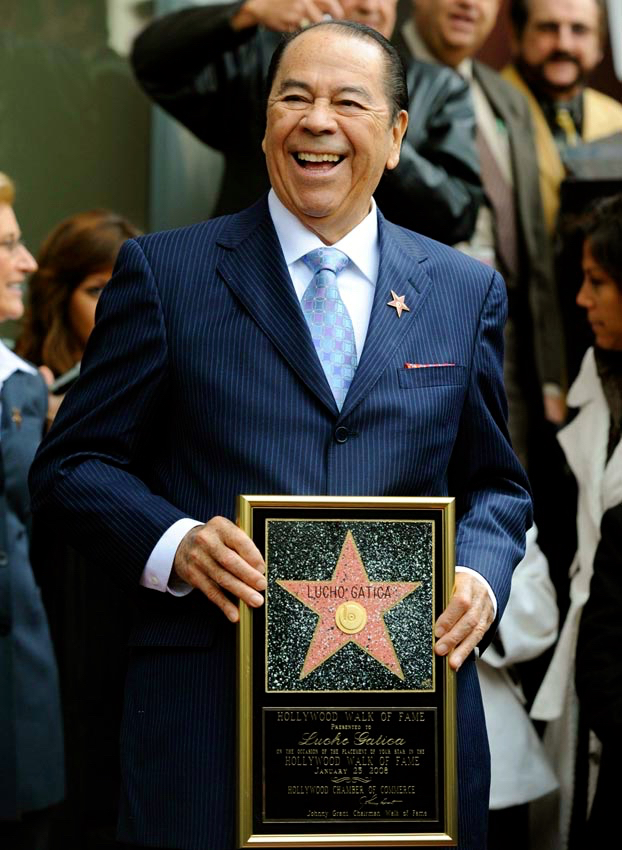

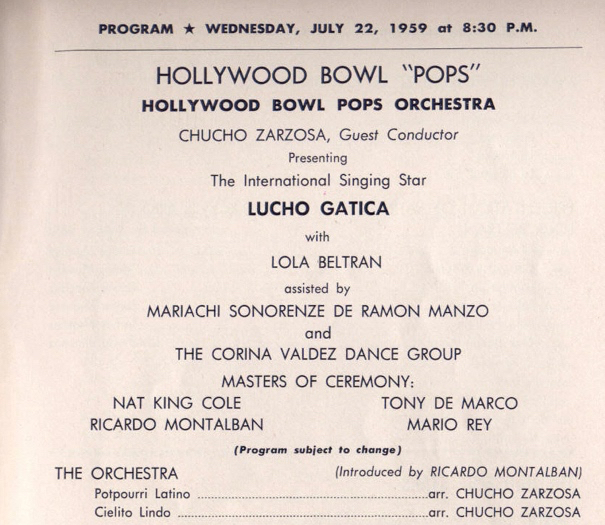

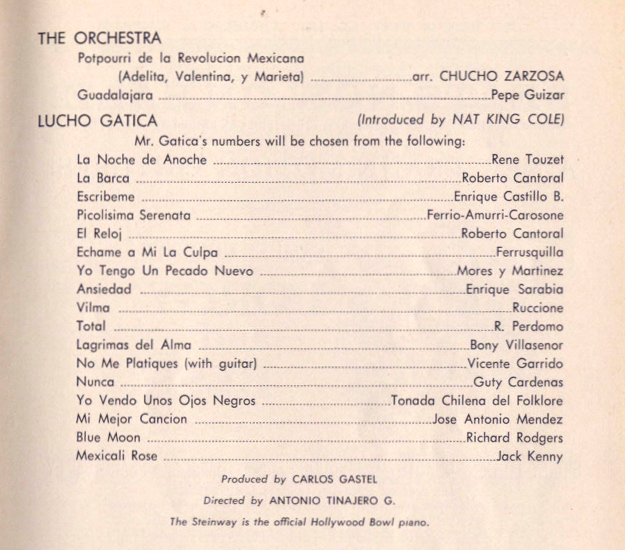

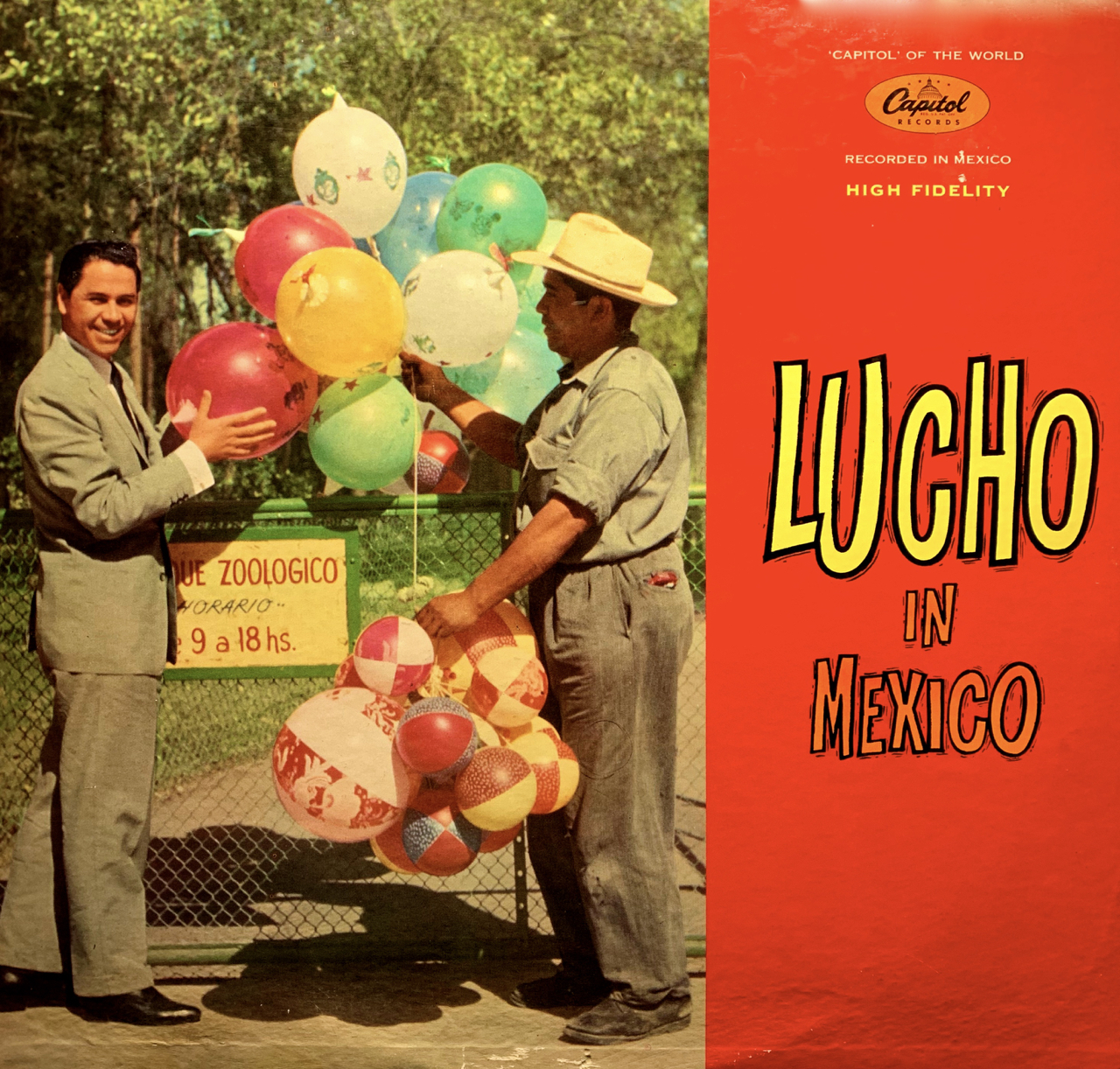

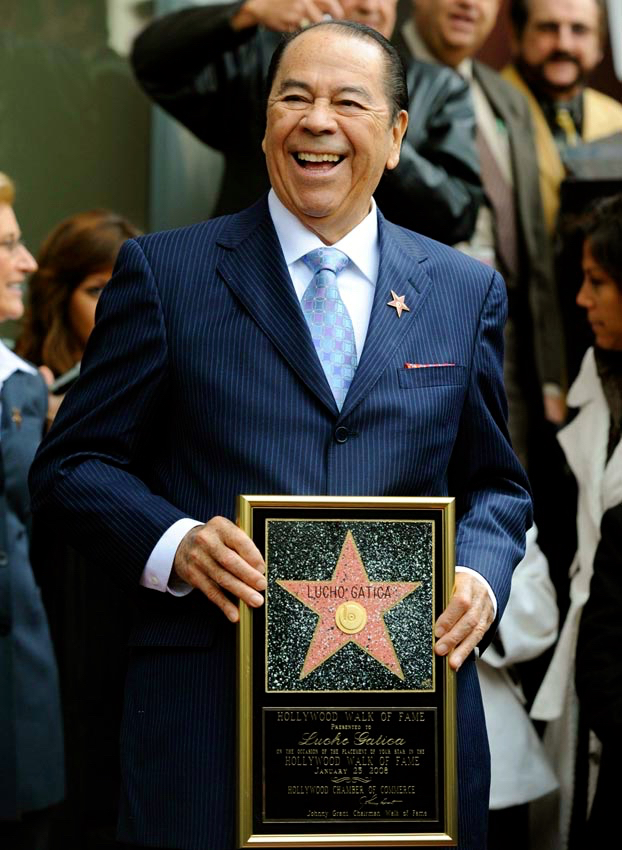

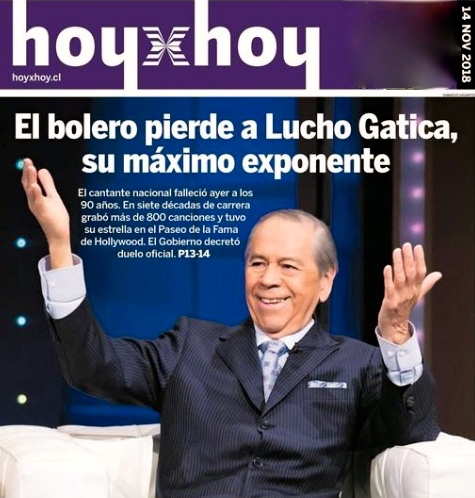

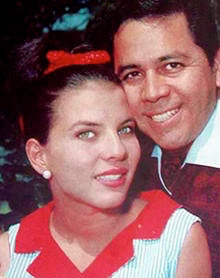

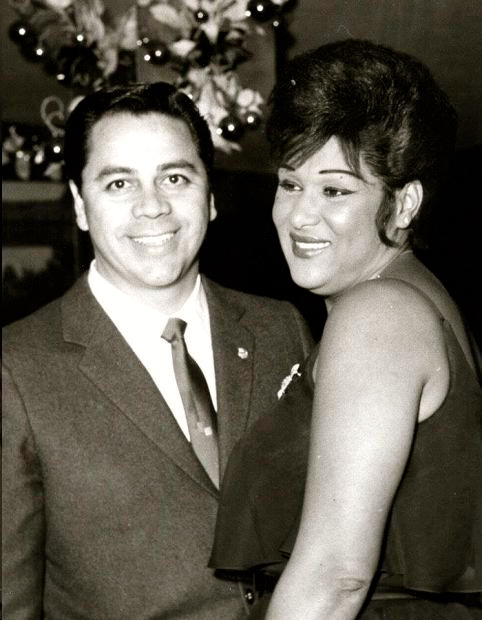

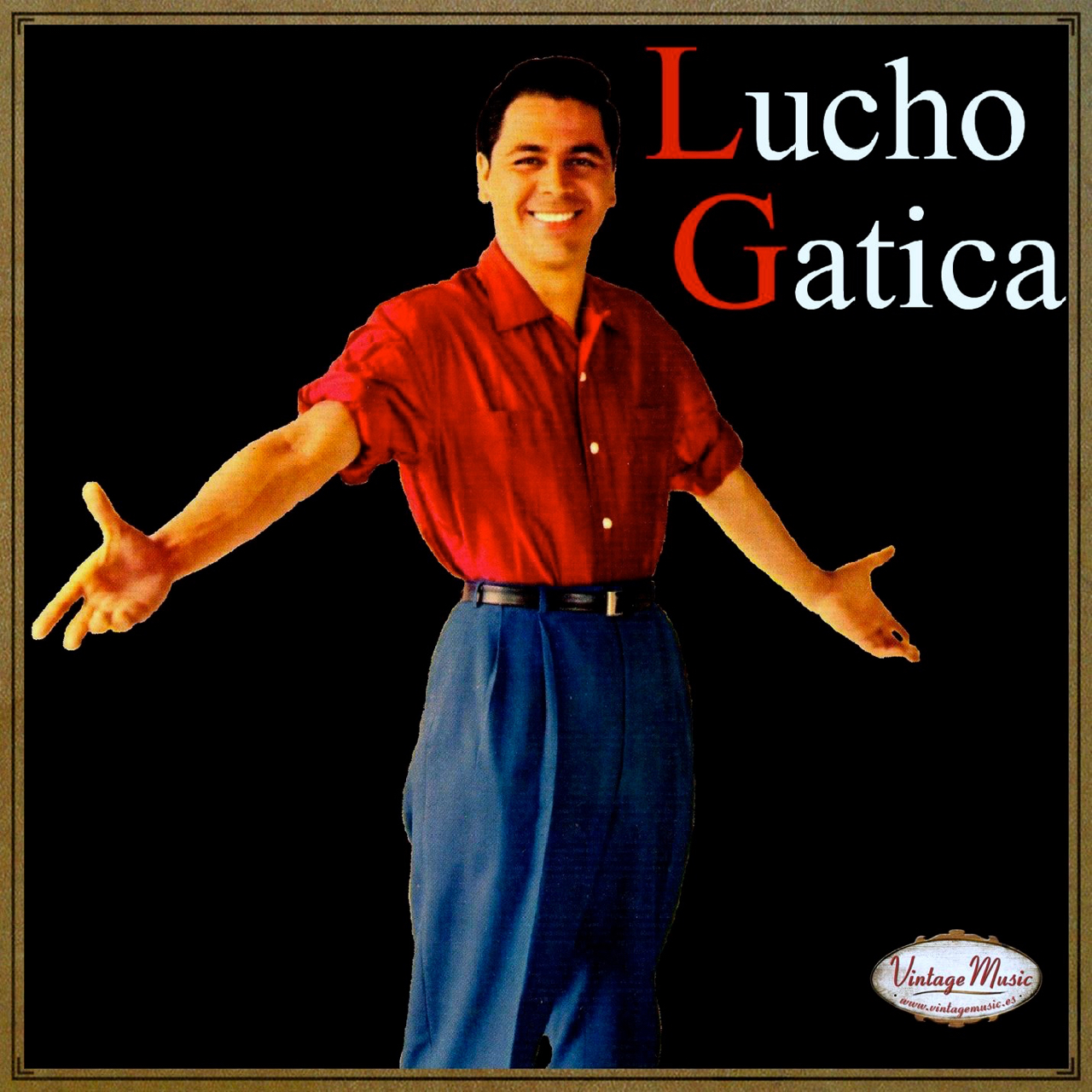

With the help of another famous comedian, Germán (“Tin Tan”) Valdés, she found her name on the marquis of El Patio, the upscale supper club that featured the biggest names in Latin American music. She was billed as “La Última Sensación en Ranchera,” sharing the stage with stars of the caliber of Jorge Negrete, Pedro Infante, Pedro Vargas, Toña La Negra, Antonio Aguilar, and Lucho Gatica.

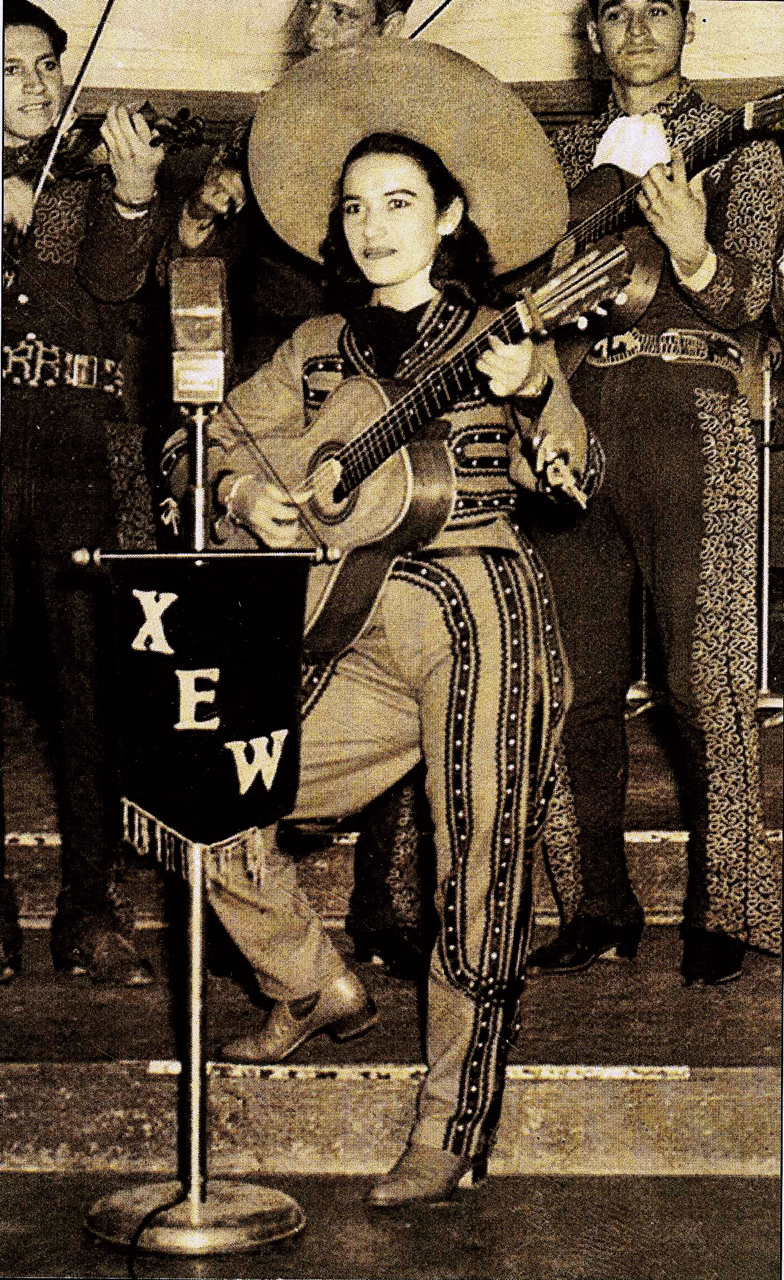

Vidaurri consolidated her new celebrity with forays into film and radio. Stunningly, she landed her own late-night program on XEW, Mexico City’s influential broadcast station, owned by media mogul Emilio Escárraga. The station had such far-reaching influence that it billed itself as "La Voz de la América Latina desde México."

Like many singing stars of her day, Vidaurri also reportedly appeared in several musical films, although IMDb, the International Movie Database, does not list her Mexican movie credits on its website.

After World War II, Vidaurri’s career took off internationally. She toured throughout Central and South America. She famously performed in Cuba with the Queen of Salsa, Celia Cruz, and the Queen of the Bolero, Olga Guillot. In New York, she appeared with Trio Los Panchos and Eydie Gorme, one of the hottest international acts at the time.

Ironically, the more famous she became and the more time she spent on tour, the more her star began to fade back home. Still, Vidaurri continued to perform and record in her hometown and throughout Texas. She played a historic role in the infancy of television in San Antonio, featured as an artist on KEYL-TV’s Spanish Varieties, “the first regularly scheduled foreign language television show in Spanish,” according to a 1951 article in Billboard Magazine. Her TV appearance was promoted as “the Villareal Brothers, with their vocalist Rita Vidaurri, who do ranchero type songs.”

By the mid-1950s, Vidaurri had made scores of recordings for Norteño, the local label founded by renowned musician and businessman José Morante. The Frontera archive contains 10 songs on five discs, all Norteño 45s, including one side featuring a duet, Rita Vidaurri Y Chicho.

Vidaurri has some three dozen recordings in the archive in a variety of styles, as a duo or solo act, most on South Texas labels. They include popular numbers such as “San Antonio Hermoso,” “Sacrificio,” “El Dinero Vale Nada,” “La Mula Bronca,” “La Esposa Del Caminante,” and “Asi Pago Yo,” the latter co-written by Chucho Navarro of Los Panchos and Mario Moreno “Cantinflas.” On some of her Falcon Records sides, Vidaurri is accompanied by pioneering conjunto leader Pedro Ayala, “El Monarca del Acordeón.”

Vidaurri has some three dozen recordings in the archive in a variety of styles, as a duo or solo act, most on South Texas labels. They include popular numbers such as “San Antonio Hermoso,” “Sacrificio,” “El Dinero Vale Nada,” “La Mula Bronca,” “La Esposa Del Caminante,” and “Asi Pago Yo,” the latter co-written by Chucho Navarro of Los Panchos and Mario Moreno “Cantinflas.” On some of her Falcon Records sides, Vidaurri is accompanied by pioneering conjunto leader Pedro Ayala, “El Monarca del Acordeón.”

The collection also contains several songs written or co-written by the singer, including all 12 tracks she recorded with her sister, as the duo Rita y Queta, for the Bluebird label. Other Vidaurri songwriting credits include “Por Que Señor,” with Trio Los Bohemios, and “Lejos de Ti,” a Fox by the duo Rita y Pepe, with Manuelillo Guerrero’s slightly jazzy accordion, on San Antonio’s Corona label.

When it came to promotion, Vidaurri took advantage of an all-American business strategy: capitalizing on her celebrity and good looks.

She won a “bathing suit and legs contest” in 1946, according to the profile by Hernández. And a decade later, her glamorous image was featured on a poster for Jax Beer, a major regional brand in those days. She was paid $500 to serve as the beer’s Mexican-American poster girl, christened La Belleza Morena de Tejas, the dark-skinned beauty of Texas.

The 1957 photo of Vidaurri, shot in New York, was a big hit. Soon, writes Hernández, “her image graced the walls of every place that sold Jax Beer in the United States.” That included the Linda Vista, Juan Vidaurri’s bar on Commerce Street in the West Side barrio, which displayed his daughter’s poster with pride.

It was proof that Rita Vidaurri had arrived. She had won not only fame, but also her father’s approval.

Personal Tragedies

Vidaurri’s professional success could not shield her from the pain of her personal life.

Twice married and twice divorced, she had a total of four children with three men, starting with twins born out of wedlock when she was 23. Her second spouse was abusive. Her third compelled her to abandon her career and become a housewife.

Her deepest wound was the loss of her three sons, who all died as young adults of different causes, at different times. Her eldest son, Leo, who earned three Purple Hearts in Vietnam, died as a result of exposure to Agent Orange during the war, according to Linda Alvarado, his twin sister and Vidaurri’s only surviving child. In a phone interview, Alvarado said her middle brother, Rogelio, also a veteran, died in an accident involving an 18-wheeler. And her baby brother, Eddie, was just 21 when he was stabbed during a dispute with his brother-in-law.

Until the day she died, Vidaurri carried in her purse the laminated photos of her three deceased sons, according to Saldaña’s obituary. One of her records, “Hijo Mio,” featured the voice of her second son Rogelio as a child.

Vidaurri was 31 in 1955 when she married Hillman Edward Eden, who was her manager and 20 years her senior. Seven years later, their son Eddie was born. According to Alvarado, Eden demanded Rita quit show business to take care of the children. The singer was reluctant to sacrifice the career she had worked so hard to build. But, as Vidaurri herself told PBS, she agreed because she considered her husband a good father, “and my children loved him.”

Vidaurri was 31 in 1955 when she married Hillman Edward Eden, who was her manager and 20 years her senior. Seven years later, their son Eddie was born. According to Alvarado, Eden demanded Rita quit show business to take care of the children. The singer was reluctant to sacrifice the career she had worked so hard to build. But, as Vidaurri herself told PBS, she agreed because she considered her husband a good father, “and my children loved him.”

The couple divorced and Eden, a World War II veteran, died of a heart attack in 1964. At 40, Vidaurri was left a single mother with four children and no means of support. She had retired from singing and remained absent from public view for the rest of the century, using her husband’s surname and living alone in a modest house. In the early 1990s, her father died at age 85. The loss added to her loneliness and sense of isolation.

All her success, all the recording and touring, had left nothing to secure her future.

“Back then, they would pay you 20 dollars to record a song, and that was it,” Vidaurri recalled in the Latino USA interview nine years ago. “We were stars at the wrong time.”

Never Too Late for a Comeback

When she re-emerged to sing again in San Antonio, a new millennium had just begun. Local fans were shocked to see her, because they thought she had died or moved to Mexico.

Vidaurri’s late-life revival didn’t happen by chance. The task of resurrecting her career fell to Graciela I. Sánchez, director of the Peace and Justice Center. Around 1999, Sanchez had read an article about two singers from the Golden Age of female Tejana stars, Rita Vidaurri and Rosita Fernández. She was moved by their stories.

“These once beautiful stars had been forgotten by San Antonio and the world,” said Sanchez in remarks at Vidaurri’s memorial service. “They felt abandoned. They wanted and needed people to remember them. They wanted to be back on stage, or at least Rita did.”

For months, Sanchez vainly tried to track down the retired singer, who was still using her married name, Eden. Then, in 2001, a mystery woman showed up at a tribute to Tejana icon Lydia Mendoza, in honor of her 85th birthday. The older woman, with a distinctive swath of gray hair atop her forehead, seemed to come “out of nowhere,” recalled Sanchez, whose center sponsored the event at downtown’s Plaza de Zacate.

“I’m Rita Eden,” the woman said.

Stunned, Sanchez gave the singer a big hug, and invited her on stage. The 77-year-old performer belted out a rousing version of the classic ranchera, “Los Laureles,” dedicated to Mendoza, who happened to be her comadre. The crowd erupted, “screaming and hollering,” as Vidaurri recalls. Afterwards, fans swarmed to greet her, thrilled to see her after so many years.

Sanchez then asked if Vidaurri wanted to resume her singing career.

“I guess so,” she said. “I don’t have Mr. Eden to stop me anymore.”

Thus began an unexpected comeback for Rita Vidaurri, one that would last almost two decades, until her death.

At the time, Vidaurri was working as a home health-care aid to make ends meet. The non-profit eventually bought her a guitar, a microphone, and a speaker for when she performed at senior centers and nursing homes.

The Esperanza Center also organized her concerts, and helped produce her new recordings. In 2004, the center celebrated Vidaurri’s 80th birthday with a show at Plaza Guadalupe, which drew hundreds, including an aging Rosita Fernandez who would pass away two years later at 88.

In conjunction with the celebration, the octogenarian released a new CD, La Calandria. It was produced with a generous assist from San Antonio music legend, the late Salomé Gutierrez, owner of another West Side cultural institution, Del Bravo Record Shop. At the time of the CD release, Vidaurri vowed it would be her last.

That prediction turned out to be a full decade premature.

Ten years later, she marked her 90th birthday with another album, Celebrando 90 Años. And she was feted with another tribute concert, again produced by the Esperanza Center. It was held May 23, 2014, at the Guadalupe Theater, where she had performed as a teenager seven decades earlier.

The year before, the busy singer drew rave reviews for her appearance at the unveiling of a commemorative stamp honoring Lydia Mendoza, also held at the Guadalupe Theater. Saldaña called it a “show-stopping, scene-stealing performance,” in an article echoing a Beatles song with the title, “S.A.'s Lovely Rita turns 89.”

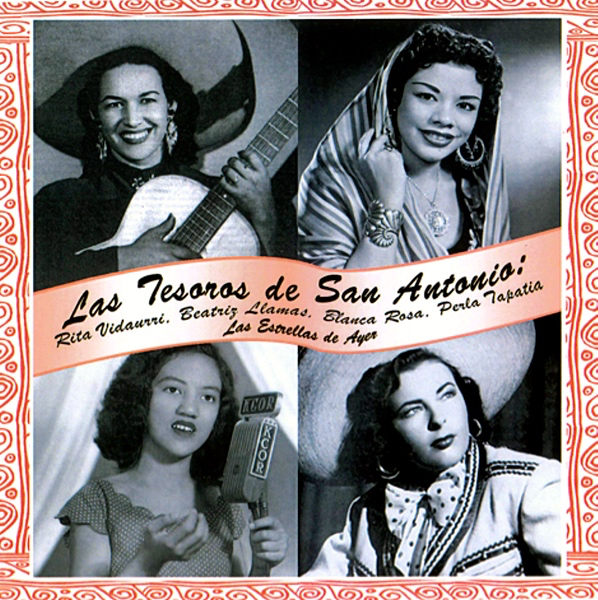

The culmination of her comeback, however, came as part of a vocal quartet that brought together other women of her era, all from San Antonio. The nostalgia group became the hottest sensation on the local music scene in years.

They called themselves Las Tesoros de San Antonio, an ensemble created in 2006. Aside from Rita Vidaurri (La Calandria), they included Blanca Rodriguez (Blanca Rosa), Beatriz Llamas (La Paloma del Norte), and Janet Cortez (Perla Tapatía), who sadly died of throat and lung cancer in 2014, at age 83.

They called themselves Las Tesoros de San Antonio, an ensemble created in 2006. Aside from Rita Vidaurri (La Calandria), they included Blanca Rodriguez (Blanca Rosa), Beatriz Llamas (La Paloma del Norte), and Janet Cortez (Perla Tapatía), who sadly died of throat and lung cancer in 2014, at age 83.

Despite the loss, Las Tesoros continued to perform as a trio. They issued a CD in 2017, Qué Cosa Es el Amor, to coincide with the 30th anniversary of the Esperanza Center, which engineered their comeback. Their story was also featured in a 2016 documentary by filmmaker Jorge Sandoval, Las Tesoros de San Antonio: A Westside Story, which debuted at the Mission Marque Plaza, site of the old Mission Drive-In Theatre in south San Antonio.

“Rita was the oldest, the strong-willed matriarch, the grand dame (of the group). Her resurgence was a reminder that she had long been a symbol of female empowerment, independence—and perseverance,” wrote Saldaña, who is now curator of the Texas Music Collection at Texas State University.

Vidaurri was honored both before and after her death. She was inducted into the National Hispanic Music Hall of Fame in 2004. Five years later, she was invited by San Antonio’s Trinity University to participate in the music department’s Legends of Texas Border Music series, which pairs guest scholars with “prominent musicians” from South Texas.

U.S. Representative Joaquín Castro of Texas paid tribute to the late singer in a floor speech on January 31, 2019. The congressman, twin brother of 2020 presidential candidate Julian Castro, called her “a pillar in our San Antonio community” and a role model for “the countless aspiring singers who look to her as a beacon of possibility.”

In her later years, Vidaurri suffered from diabetes, had three heart attacks, and underwent a quadruple bypass. Toward the end, her daughter said, people urged her mother to slow down for health reasons. But Rita wouldn’t hear of it.

In her later years, Vidaurri suffered from diabetes, had three heart attacks, and underwent a quadruple bypass. Toward the end, her daughter said, people urged her mother to slow down for health reasons. But Rita wouldn’t hear of it.

Vidaurri’s last formal public performance took place at the Esperanza Center on November 1, 2018, with Las Tesoros. But informally, she appeared religiously every Tuesday and Thursday morning at a San Antonio restaurant called Flor de Chiapas. A corner booth was always reserved for her and a small group of fellow musicians who gathered for the friendly sing-alongs. Vidaurri attended until she was literally too sick to make it.

In her last days in hospice care, some of those same musicians brought the serenade to Vidaurri’s bedside. As they sang some favorite tunes, the ailing artist managed a smile and tried to whisper words with her last breath.

"She moved her mouth like she wanted to sing along with them," Alvarado recalled in a local TV interview. "And everybody just started crying."

In that moment, Rita Vidaurri Eden fulfilled her final wish.

"When I die,” she would say, “I'm going to die singing."

– Agustín Gurza

Blog Category

Tags

Images