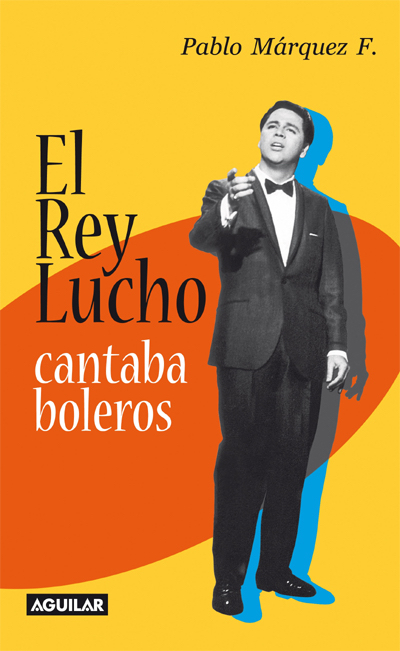

Artist Biography: Lucho Gatica, Rey del Bolero, Part 1

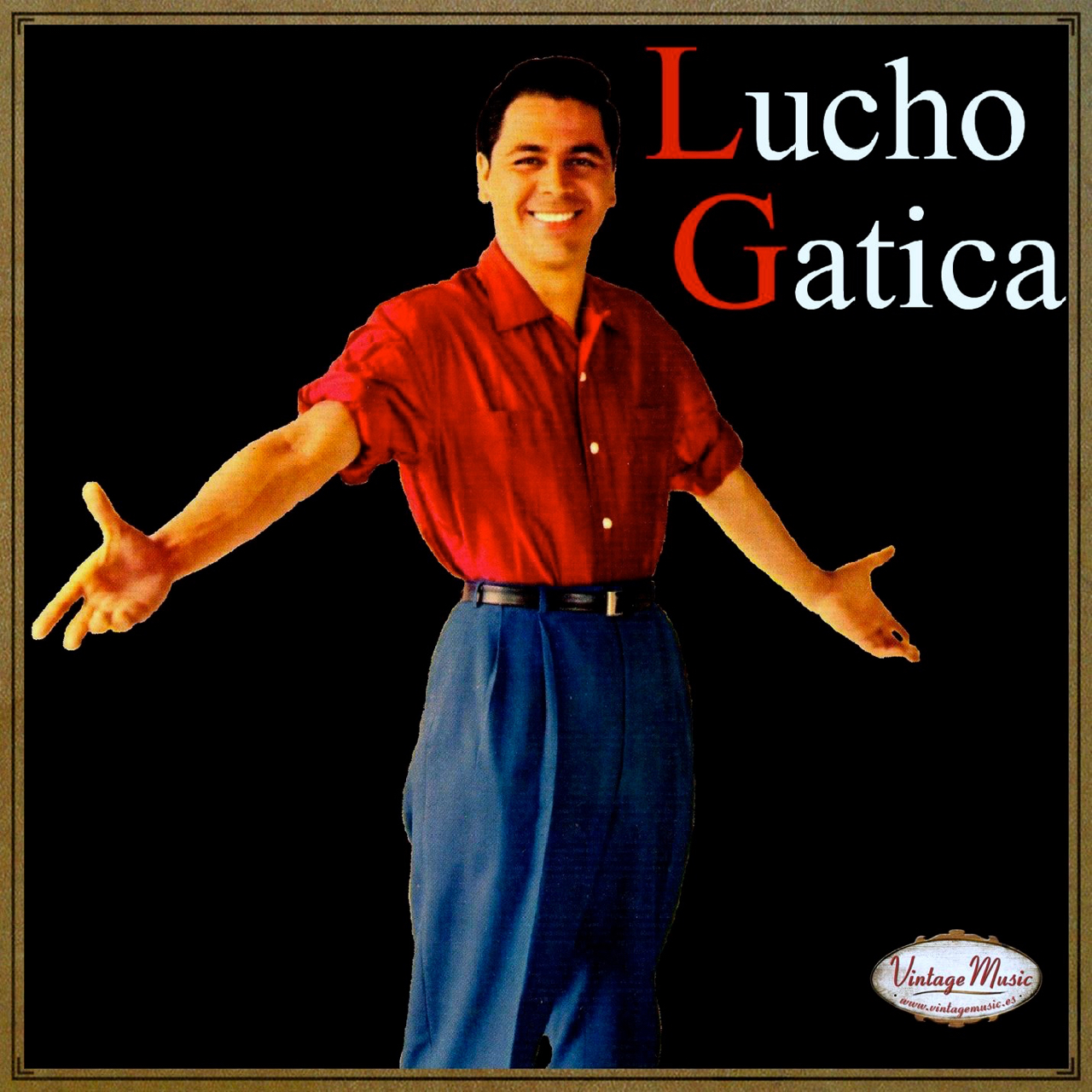

During most of the 20th century, the world of Latin pop music was dominated by a handful of countries – Mexico, Cuba, Argentina, and of course, Spain. But in the 1950s, an exception to that rule became a sensation. His name was Lucho Gatica, and he came from Chile.

During most of the 20th century, the world of Latin pop music was dominated by a handful of countries – Mexico, Cuba, Argentina, and of course, Spain. But in the 1950s, an exception to that rule became a sensation. His name was Lucho Gatica, and he came from Chile.

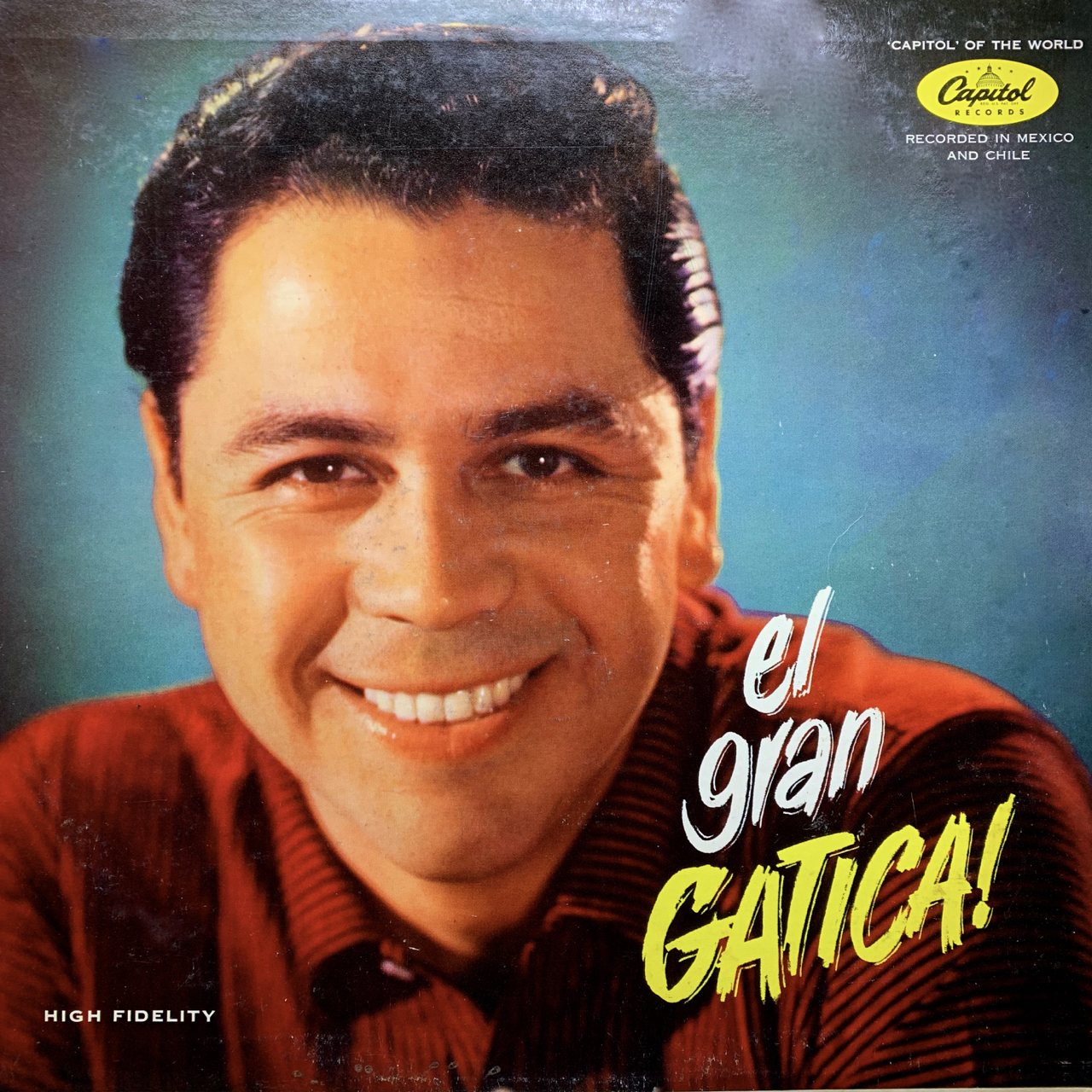

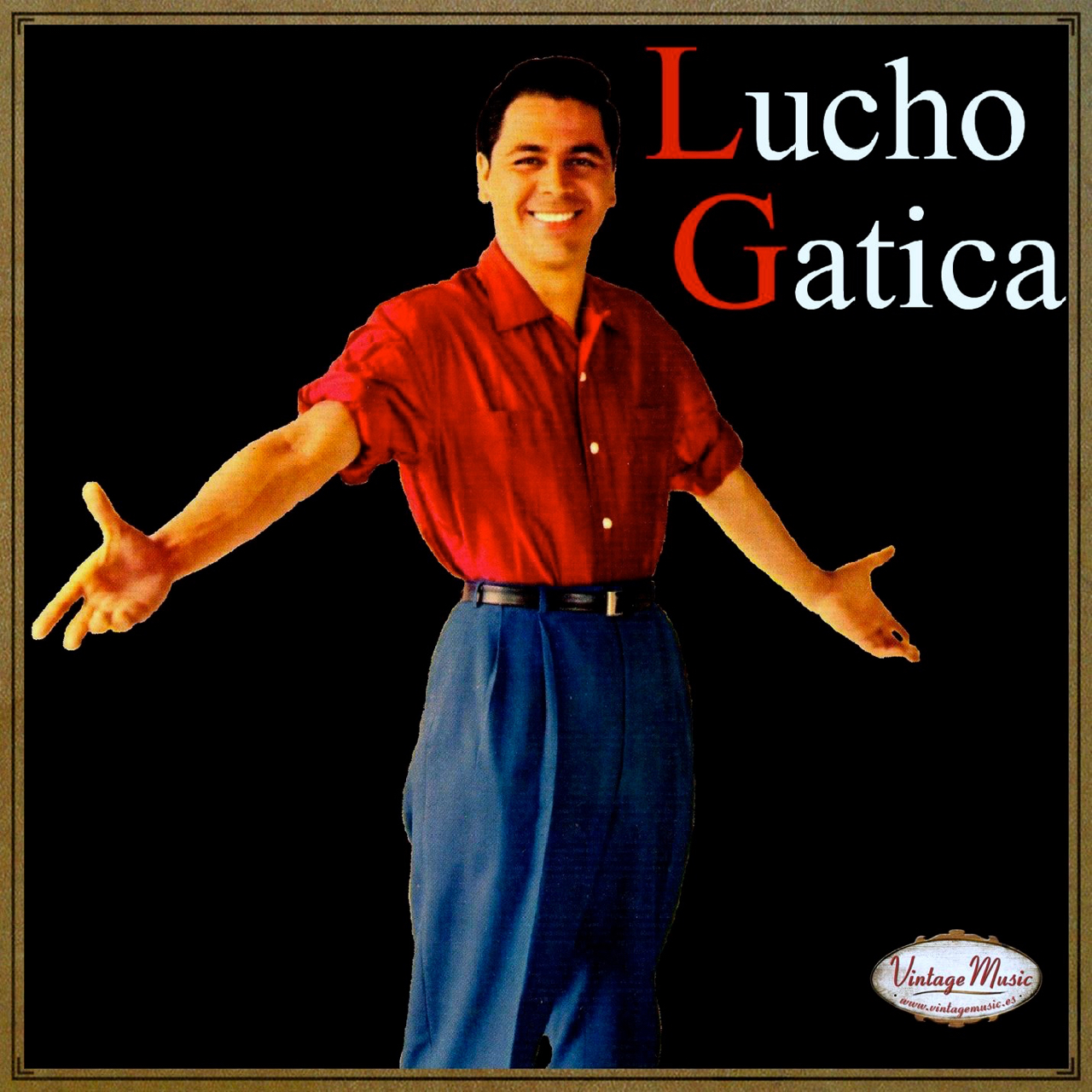

Gatica emerged from a small town in central Chile to become one of the most popular Latin American vocalists of all time. In a career that spanned 70 years, he sold millions of records around the world, packed theaters and stadiums from Madrid to Manila, starred in movies, and became a celebrity in Hollywood where his friends included Frank Sinatra and Ava Gardner.

The singer’s success was built on his unique ability to convey the romantic, lyrical, and passionate essence of the song style known as the bolero. His repertoire includes many distinctive interpretations of compositions still considered classics of the genre. Add to that his matinee-idol good looks and his on-stage charisma, and Gatica was destined for superstar status.

Last month, the voice of the artist known as El Rey del Bolero was silenced forever. Gatica passed away at his home in Mexico City. He was 90.

“Lucho Gatica has his name inscribed on the hearts, not only of Chileans of all ages, but also of romantics everywhere,” said Education Minister Mariana Aylwin in 2002 on the artist’s 50th anniversary when he was given his nation’s top award in the arts. “For entire generations, his name has been almost synonymous with love. He is a man who has turned many strangers into lovers.”

Gatica was one of the few pop artists who managed to survive the ups and downs of the fickle music market. As the years went by, he was often asked for his thoughts about the latest trends.

"There is certainly less romanticism nowadays,” he once said. “But we must accept that young people have their own rhythms, their own style of singing. I respect that because I believe every artist has their own time. And mine was wonderful.”

A Native Son of Rancagua

Luis Enrique Gatica Silva was born on August 11, 1928, in Rancagua, a regional capital known for its wines and its copper mines. His father, José Agustín Gatica, was a merchant and small farmer. His mother, Juana Silva, was a homemaker who had a passion for music. As the youngest of seven siblings, his childhood nickname was “Pitico.”

Lucho was only four when his father died, and his widowed mother went to work a seamstress to raise her children. The family banded together to face the hardships, and music always managed to lighten the burden. While Mrs. Gatica played harp and guitar, Lucho’s older brothers sang tangos and tonadas, from the regional folklore that would inform Lucho’s early work as a professional singer.

It was his brother Arturo, seven years his senior, who led the way in the music business. Arturo started singing professionally in Rancagua when Lucho was only ten, a shy boy who would hide behind the door when the family gathered for sing-alongs at home. But Arturo recognized his little brother’s talent early, and encouraged him to sing.

It was his brother Arturo, seven years his senior, who led the way in the music business. Arturo started singing professionally in Rancagua when Lucho was only ten, a shy boy who would hide behind the door when the family gathered for sing-alongs at home. But Arturo recognized his little brother’s talent early, and encouraged him to sing.

“So it was my brother who had an enormous influence on my career,” Gatica told journalist Marisol García in a 2007 interview published in La Nación Domingo. “He was already singing on the radio and he would always say, ‘When are you going to join me?’ I never wanted to, until one day we formed a duo. That’s when I started to take singing seriously. Arturo later told me that he had realized I sang better than he did, which was not the case, obviously.”

Lucho attended the Instituto O’Higgins, an all-boys Catholic school run by the Marist Brothers in his hometown. He started performing in Chile’s so-called “revistas de gimnasio,” an annual student showcase of athletic and artistic skills.

In 1941, the two brothers appeared as a vocal duo on local radio. Lucho was just 13, but already his emotive voice was drawing attention. Two years later, the aspiring singer made his first recordings in the same broadcast studio, performing three folkloric songs, including “Negra del Alma.”

By 1945, the two singing siblings had relocated to Santiago, the nation’s capital about 50 miles to the north. Lucho, then 18, continued his studies at another Marist school, the Instituto Alonso de Ercilla. He then enrolled to become a dental technician but never practiced dentistry because his singing career took off so quickly.

Arturo introduced Lucho to Raúl Matas, an influential deejay at Santiago’s Radio Minería, which reached a nationwide audience. The young Lucho soon made his national debut on the host’s popular show, “La Feria de los Deseos,” with the song “Tú, Dónde Estás,” a prototypical bolero of yearning for lost love. The connection with the deejay also led to Lucho’s first recording contract, with the international Odeon label, which later became part of EMI.

Lucho’s professional recording debut came in 1949, again in a duet with his brother. Backed by the Dúo Rey-Silva, the brothers recorded four tonadas, a folkloric style of song and dance. The 78-rpm disc included the titles: “El Martirio,” “Tú Que Vas Vendiendo Flores,” “La Partida,” and “Tilín Tolón.”

Early on, the Gatica brothers focused on the rich folklore of their native country. The duo appeared on the cover of the magazine Ecran, dressed in the traditional style of the rural huaso, the Chilean charro.

Lucho was also fond of the native music of neighboring Argentina, including the tango, which was enormously popular in Chile during the 1940s. In a 1990 interview in Barcelona, Lucho called himself a pioneer of South American folk music, claiming to be the first to record the songs of Argentina’s Atahualpa Yupanqui, including “Los Ejes de Mi Carreta,” the revered songwriter’s most famous composition.

"I started out doing folk music, but it went very bad for me,” said Lucho, who told the interviewer he still carried a letter from Yupanqui in his suitcase as a keepsake. “At that time, there was no interest in South American folklore, so I turned my attention to boleros instead.”

The timing of Gatica’s stylistic switch could not have been better. It came at the dawn of the 1950s, the beginning of what would become known as the genre’s golden era. Gatica was a natural star—confident, handsome, and ambitious. His one desire was to stand out as a singer.

He did so with a style that was sensual, intimate, and instinctive. Moreover, he brought a fresh approach to the romantic song, breaking with the formal, old-school method, which was more concerned with technique than feeling.

“This was a new bolero,” writes David Ponce, an author specializing in the music of Chile. “In Gatica’s voice, formal recital turned into soft phrasing, and the rhythm became less marked, and more modulated. In the history of the bolero, Gatica did the equivalent of what Sinatra did for the popular American songbook, and to the same effect: gaining intimacy and closeness with the audience.”

That one-on-one intimacy would only be possible as a solo act, and circumstances conspired to let Lucho go it alone.

That one-on-one intimacy would only be possible as a solo act, and circumstances conspired to let Lucho go it alone.

In 1952, his older brother got married and formed a new act with his wife, Hilda Sour, calling themselves Los Chilenos. (Arturo, Lucho, and Hilda had starred together in the 1950 Chilean film Uno Que Ha Sido Marino.) The following year, the newlyweds left on a world tour of three continents that would keep them away from home for six years. Arturo would later say that there had been a falling out between him and Lucho, and that the brothers didn’t speak for years, although they later reconciled.

Back home, Lucho’s career was taking off. His success would spark a phenomenon that had not been seen before in Latin America, one that would become the stuff of both cheap tabloids and lofty literature.

They called it Luchomania.

The Decade of the Bolero

The bolero in popular music, as opposed to the much older Spanish dance of the same name, has its roots in Santiago de Cuba in the late 1800s, specifically in the style known as trova. In the first decades of the 20th century, the bolero’s popularity expanded worldwide with the growth of the commercial recording industry.

The best boleros have become part of the Latin American songbook, and the top composers have achieved hallowed status in the pantheon of Spanish-language songwriters. Within the Frontera Collection, the bolero ranks No. 2 in the list of the top 20 genres, as reported in the book, The Arhoolie Foundation’s Strachwitz Frontera Collection of Mexican and Mexican American Recordings.

During the 1940s, when Lucho Gatica was still a schoolboy in Rancagua, the bolero gained a foothold in English-language markets, partly through popular films of the day. One of the treasured gems of the genre, “Bésame Mucho,” written by Mexico’s Consuelo Velazquez, became a global hit after it was featured in the 1944 Hollywood musical Follow the Boys, performed by Charlie Spivak and His Orchestra. Gatica would later have a huge hit himself with his interpretation of the song, smoldering with desperate desire. And in the early 1960s, The Beatles recorded their own rendition, with English lyrics.

In tributes to Gatica after his death, several writers mentioned the Beatles cover version, suggesting the fabled band had discovered the tune via the Chilean singer’s recording. But Paul McCartney has said that he first heard “Bésame Mucho” in an upbeat R&B version by the Coasters.

This oft-mentioned anecdote reflects a tendency in posthumous tributes to overstate Gatica’s influence on the genre. The bolero already had several popular interpreters during the 1930s and 40s, including Pedro Vargas, Trio Lo Panchos, Alfonso Ortiz Tirado, María Teresa Vera, Agustín Lara and OIga Guillot. Cuba and Mexico were the reigning powerhouses of the genre, brimming with top singers and composers, long before Gatica entered the arena.

Gatica himself acknowledges his predecessors.

“I always listened to Leo Marini, Pedro Vargas, Hugo Romani,” he told Chile’s “El Mercurio” newspaper in 1997. “I remember (Colombia’s) Trío Martino came to Chile, and they brought with them the most marvelous boleros, among them, ‘Contigo en la Distancia’ and ‘Nosotros.’ Also visiting were (Mexico’s) Los Tres Diamantes, who sang like gods.”

“I always listened to Leo Marini, Pedro Vargas, Hugo Romani,” he told Chile’s “El Mercurio” newspaper in 1997. “I remember (Colombia’s) Trío Martino came to Chile, and they brought with them the most marvelous boleros, among them, ‘Contigo en la Distancia’ and ‘Nosotros.’ Also visiting were (Mexico’s) Los Tres Diamantes, who sang like gods.”

Gatica does deserve credit for spreading the genre’s popularity, and in some cases making definitive versions of beloved classics. He also had a golden touch for repertoire. He knew instinctively which songs would fit his style. And many of them became hits.

In Santiago, Gatica was exposed to prominent artists from other countries, who shared their music and opened doors for him internationally. In 1951, he met the Cuban singer Olga Guillot, thanks again to an introduction by his brother. And she shared the latest boleros written by her compatriots, pioneer of the style Cubans called “feeling,” or fílin.

“Lucho was thrilled with this new style of bolero,” Guillot told Ena Curnow of Miami’s El Nuevo Herald in 2012, “and he learned ‘La gloria eres tú,’ ‘Contigo en la distancia,’ ‘Delirio,’ and other numbers.”

Also in 1951, Gatica recorded “Piel Canela,” the tropical favorite written by Puerto Rico’s Bobby Capo. He was backed on the Odeon disc by the orchestra of Don Roy, but some critics complained that the accompaniment overshadowed the vocalist.

The following year, he switched to a softer sound with backing by the guitar trio Los Peregrinos, whom he met through deejay Mátas. The trio had been newly formed in Santiago by Bolivia’s Raul Shaw Moreno, known for his stint with Trio Los Panchos. The label convinced the visiting musician to let his group record with Gatica.

Those Odeon sessions in 1952-53 marked the inauguration of his reign as “The Bolero King,” with songs such as the aforementioned “Contigo en la Distancia” by César Portillo de la Luz and “Sinceridad,” by Rafael Gastón Pérez, which became his first big hit in Brazil. Other tracks with Los Peregrinos included "En Nosotros," "Amor, Qué Malo Eres," "Amor Secreto,” and “Vaya con Dios.”

On the Move

Gatica’s meteoric rise launched him on a series of international tours that would keep him constantly on the road for a decade. He appeared in Cuba for the first time in 1952, as a guest of Guillot. His performances at Havana’s Teatro Blanquita and the fabled Tropicana nightclub are still considered legendary in Cuba, the cradle of the bolero. The singer also made his first television appearance on the island which, according the Cuban website EcuRed, “brought daily life to a stop because everybody wanted to see and hear the King of the Bolero.”

Gatica’s meteoric rise launched him on a series of international tours that would keep him constantly on the road for a decade. He appeared in Cuba for the first time in 1952, as a guest of Guillot. His performances at Havana’s Teatro Blanquita and the fabled Tropicana nightclub are still considered legendary in Cuba, the cradle of the bolero. The singer also made his first television appearance on the island which, according the Cuban website EcuRed, “brought daily life to a stop because everybody wanted to see and hear the King of the Bolero.”

Gatica’s first international tour came the following year, taking him to Colombia, the U.S., Spain and finally England, where he recorded at the EMI studios that would later become known as Abbey Road.

The British label matched Gatica with another of their artists, Scottish pianist and bandleader Roberto Inglez (born Robert Inglis), who worked with a young producer named George Martin, later of Beatles fame. The transcontinental collaboration yielded four songs: two in Portuguese, “Samba Chamou” and “No Tem Soluçao,” and two in Spanish, “Las Muchachas de la Plaza España” and the evergreen “Bésame Mucho”.

Inglez and his orchestra joined Gatica in Chile in 1954, and the two artists set out on an international tour that caused pandemonium at almost every stop. In Lima, the sensation caught the attention of Peruvian novelist Mario Vargas Llosa. In his book, La Tía Julia y el Escribidor, the writer describes frenzied female fans pursuing the sexy singer until he was left in just his shoes and shorts.

Gatica sparked the same furor in Buenos Aires, Uruguay, and Brasil. “Females went after a piece of anything that belonged to their idol: a lock of hair, a handkerchief, a sleeve of his shirt … anything,” writes Omar Martinez, on the blog Luchoweb.

By 1955, Gatica was at the top of his game. He was ready for his next big move: establishing his home in Mexico City, bolero capital of the world.

– Agustín Gurza

Read Artist Biography: Lucho Gatica, Rey del Bolero, Part 2.

Blog Category

Tags

Images