Artist Biography: Pedro Ayala, El Monarca del Acordeon

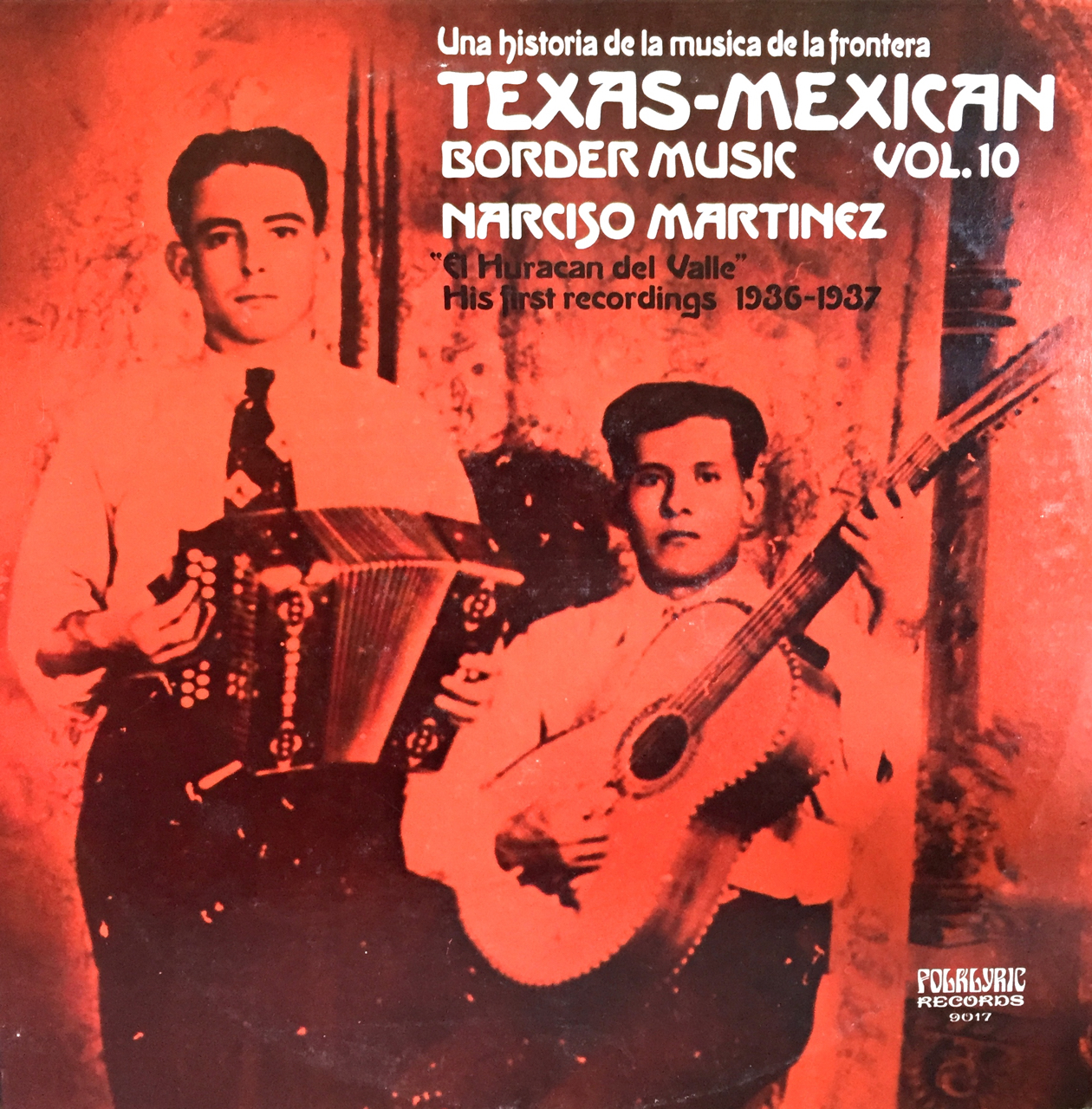

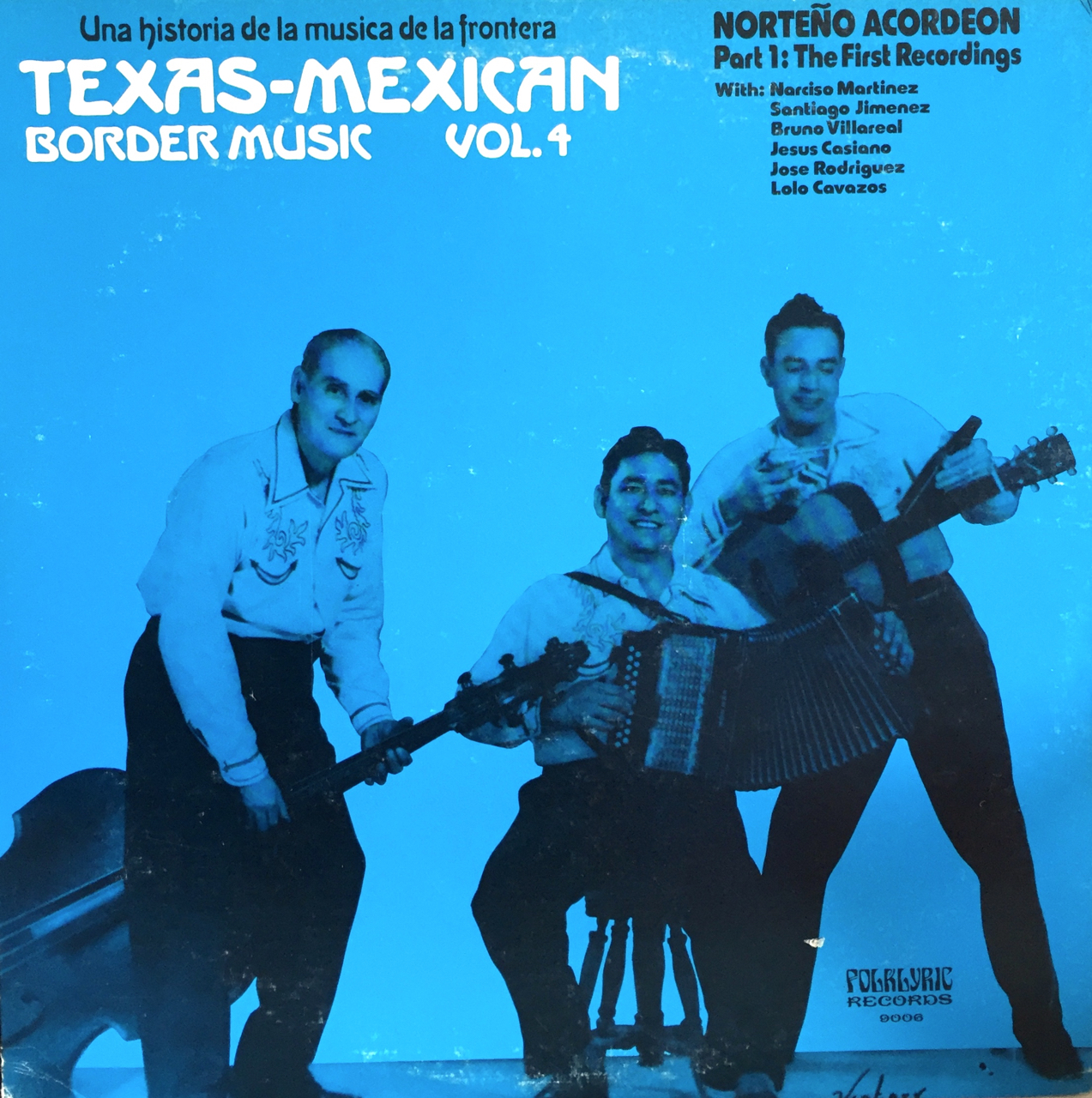

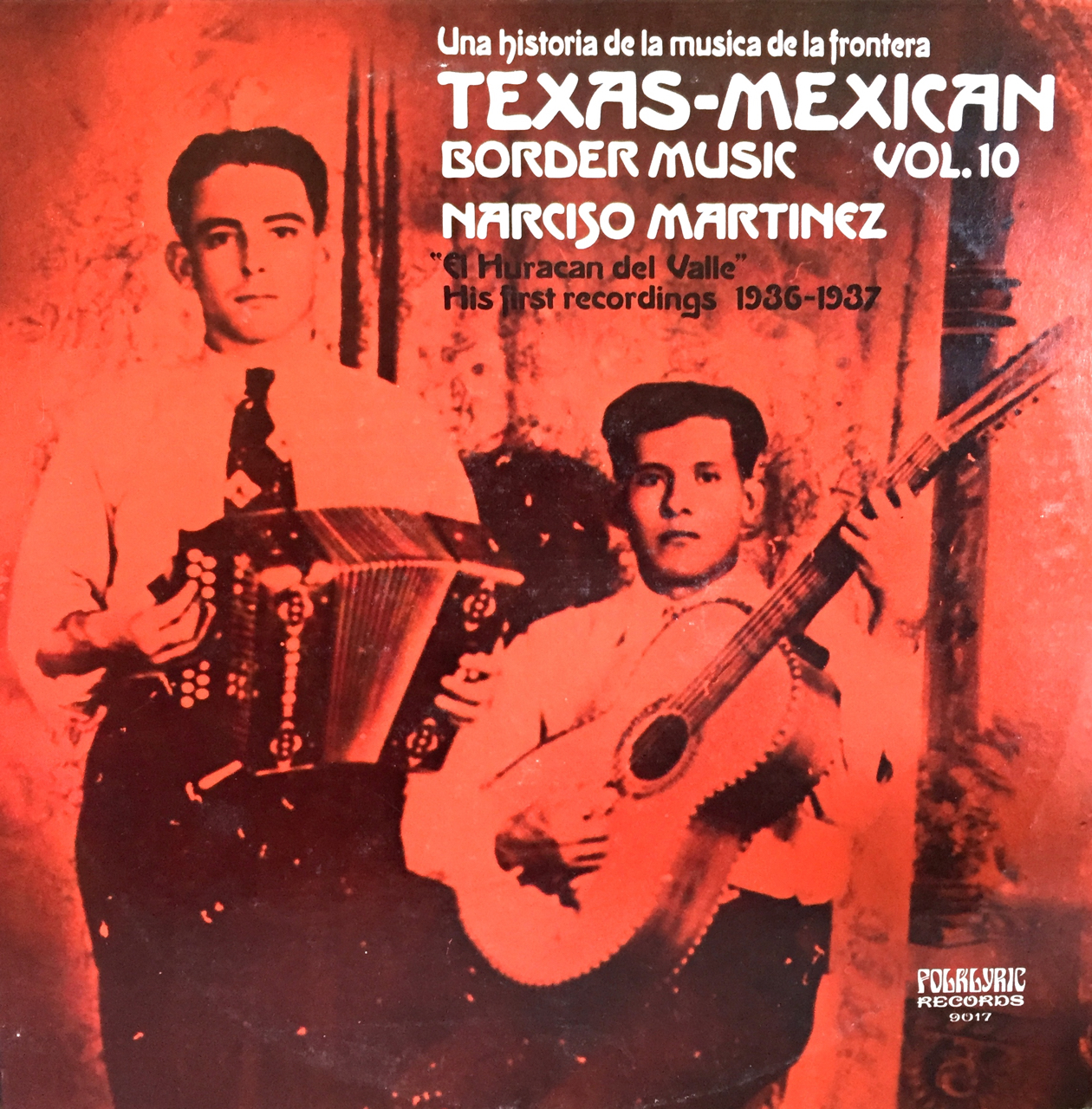

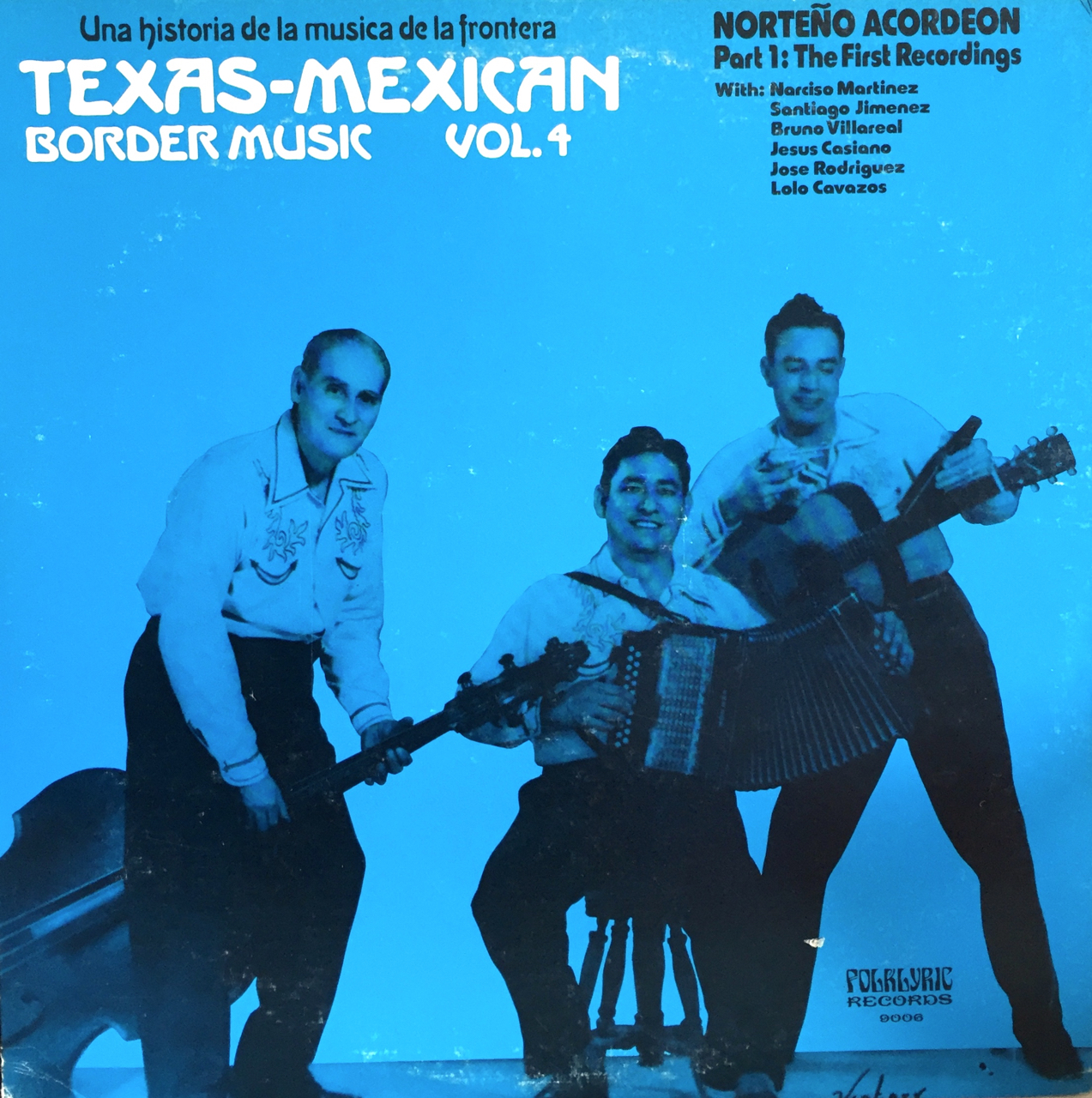

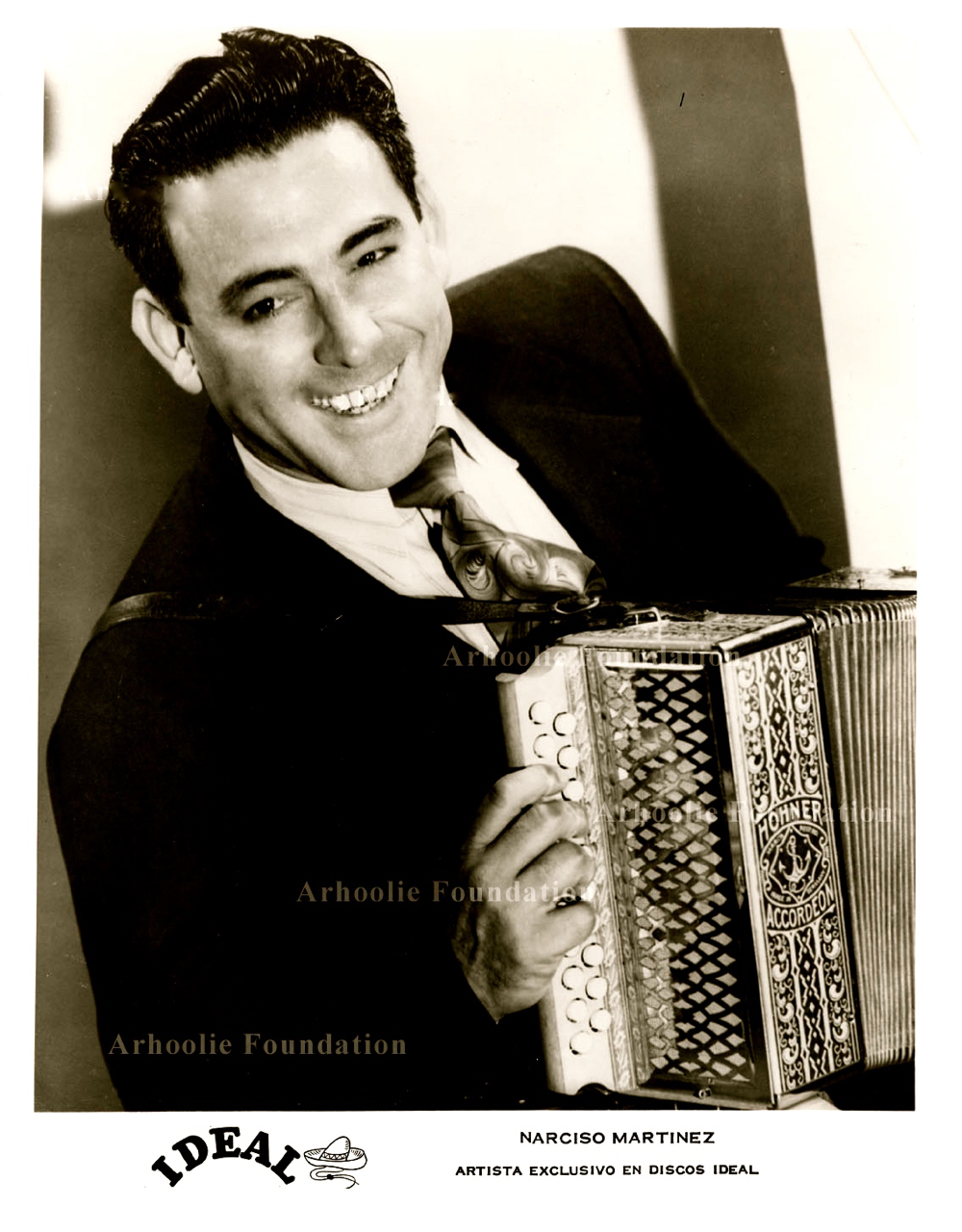

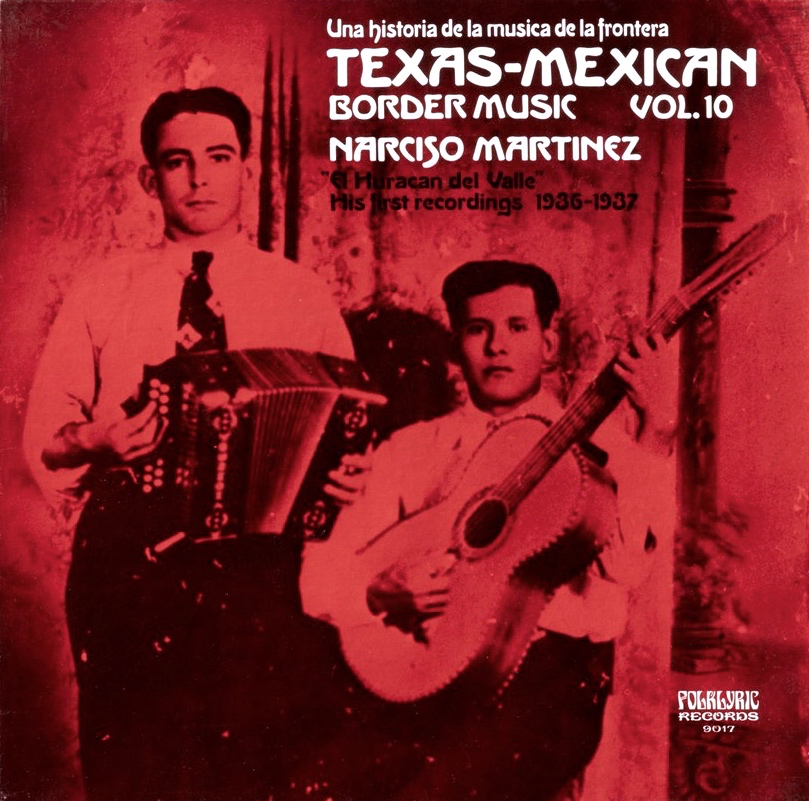

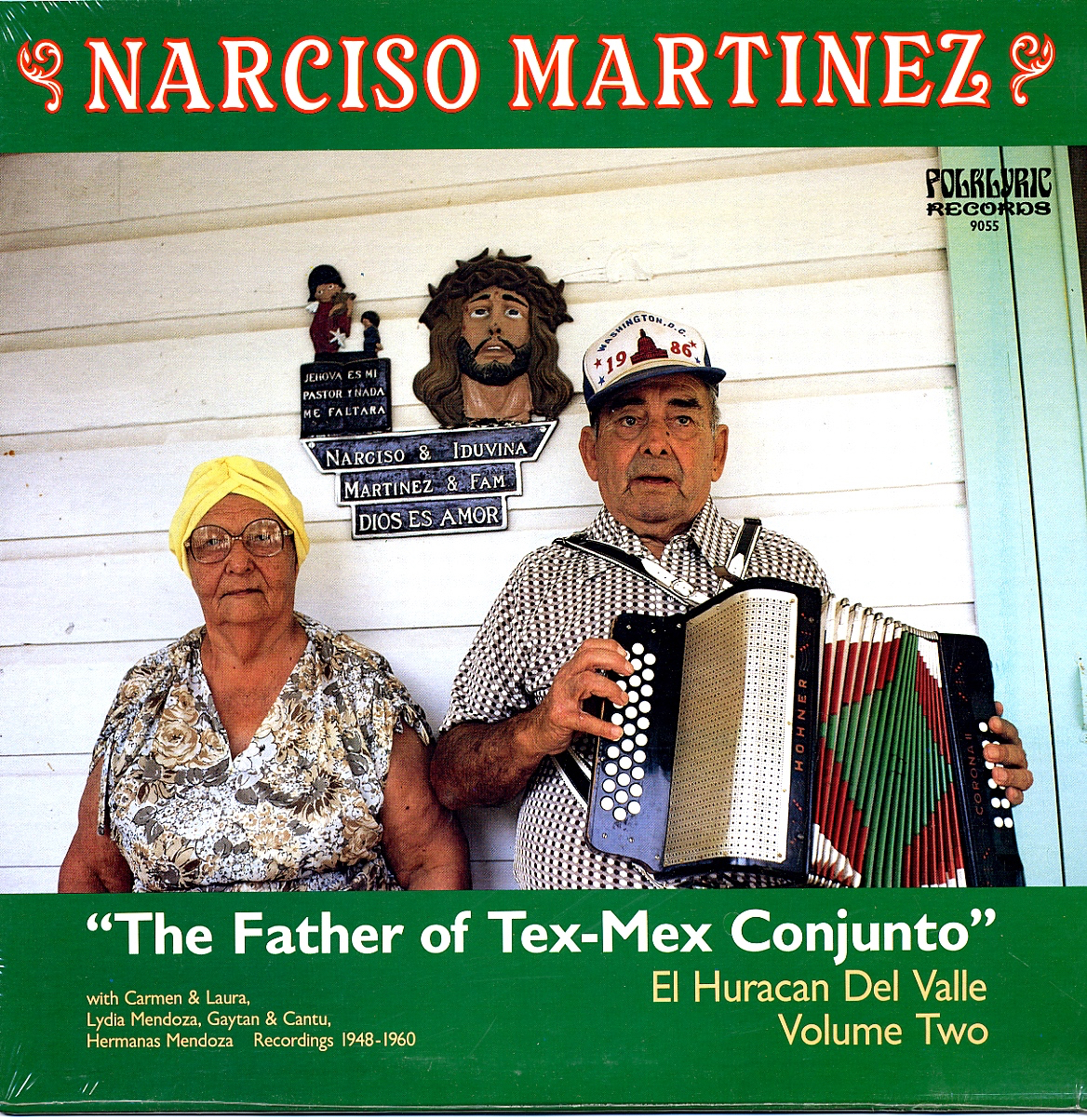

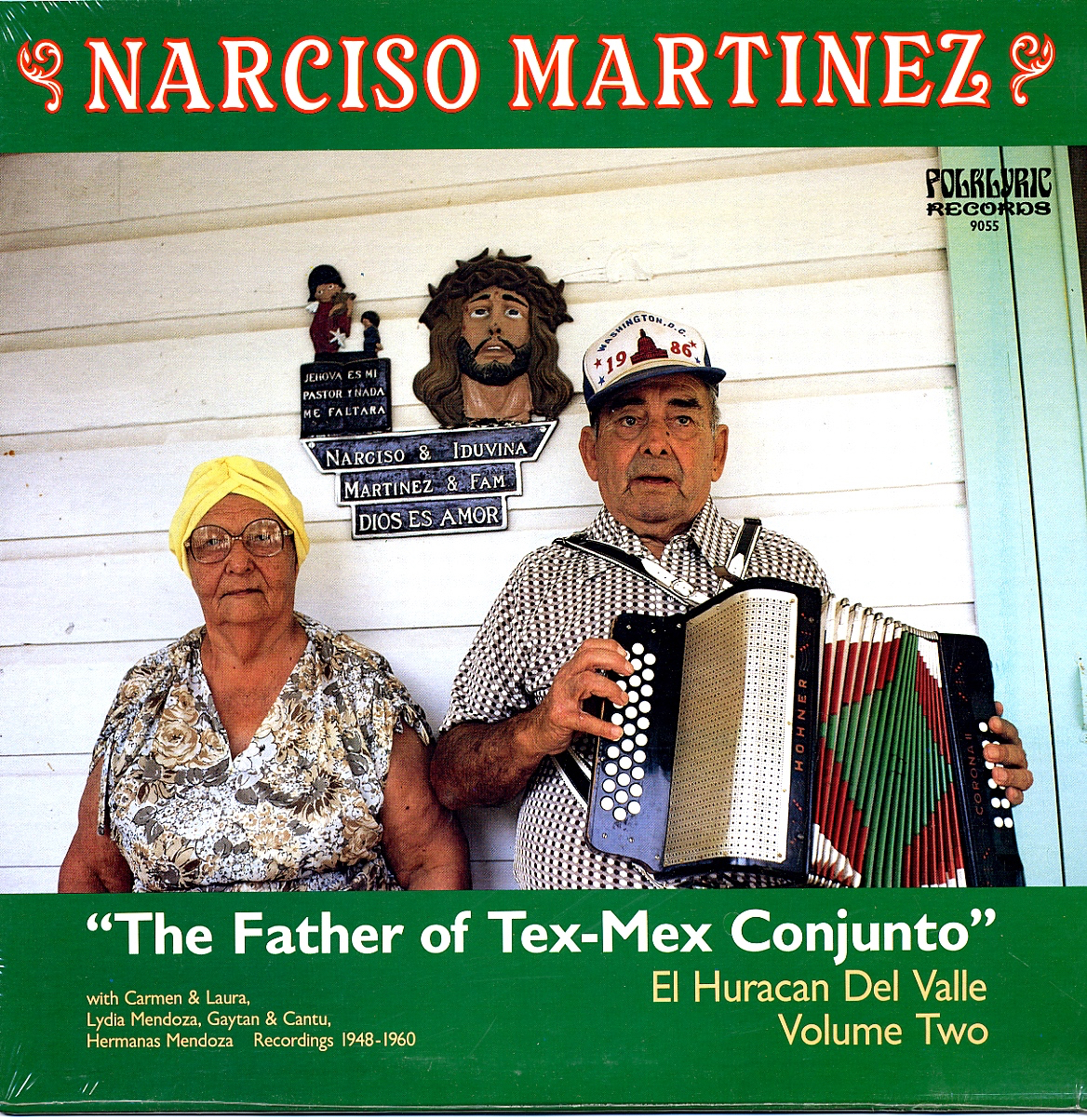

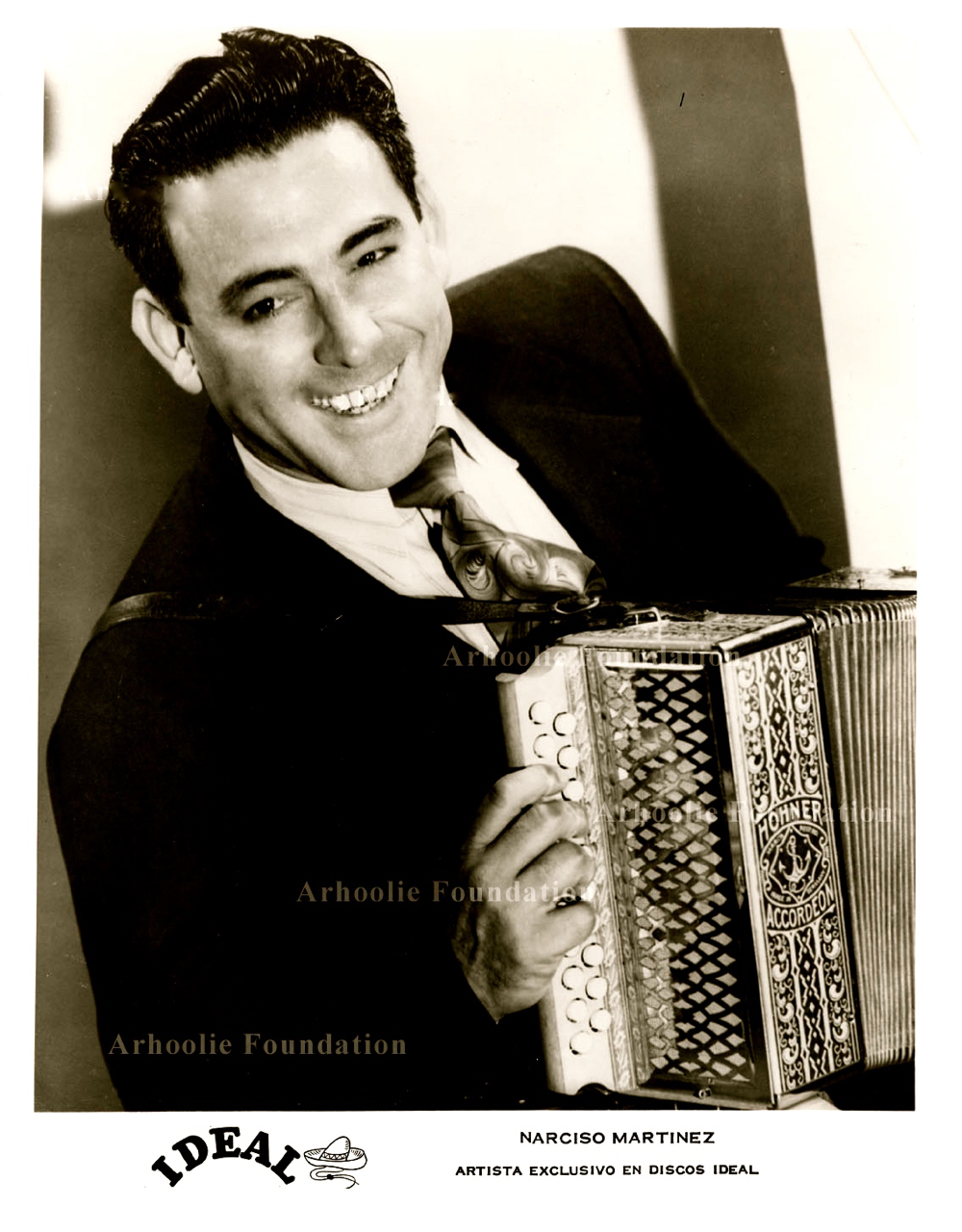

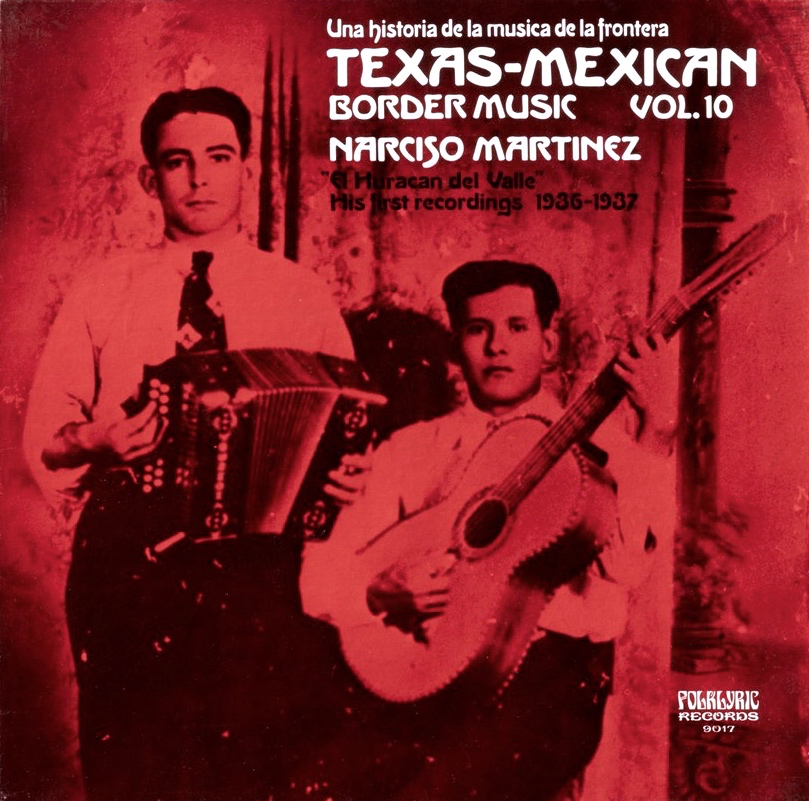

The pantheon of pioneers in conjunto music includes artists who are household names to fans and students of the genre. Among the most recognized are names such as Santiago Jimenez and especially Narciso Martinez, hailed as the father of the conjunto style. Although not as well-known as his celebrated contemporaries, accordion-player Pedro Ayala deserves recognition for his contributions to the early development of this grassroots style during the 1930s and 1940s.

The pantheon of pioneers in conjunto music includes artists who are household names to fans and students of the genre. Among the most recognized are names such as Santiago Jimenez and especially Narciso Martinez, hailed as the father of the conjunto style. Although not as well-known as his celebrated contemporaries, accordion-player Pedro Ayala deserves recognition for his contributions to the early development of this grassroots style during the 1930s and 1940s.

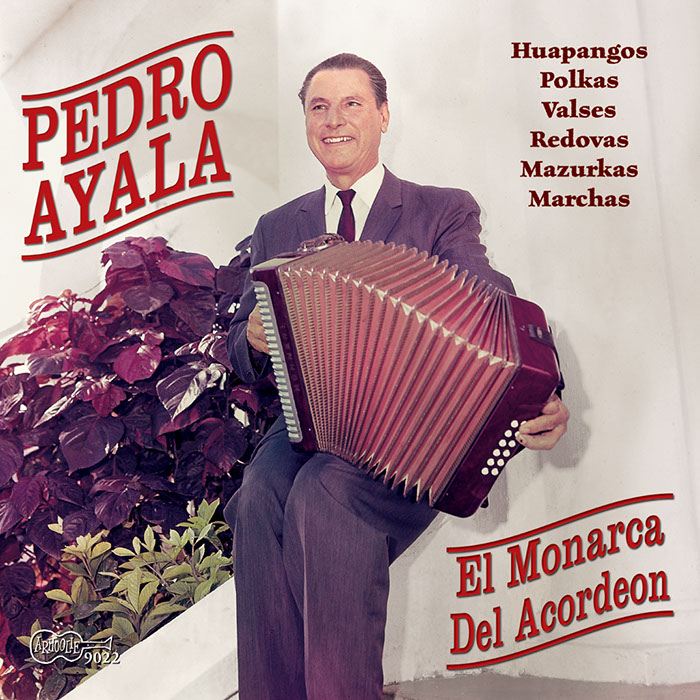

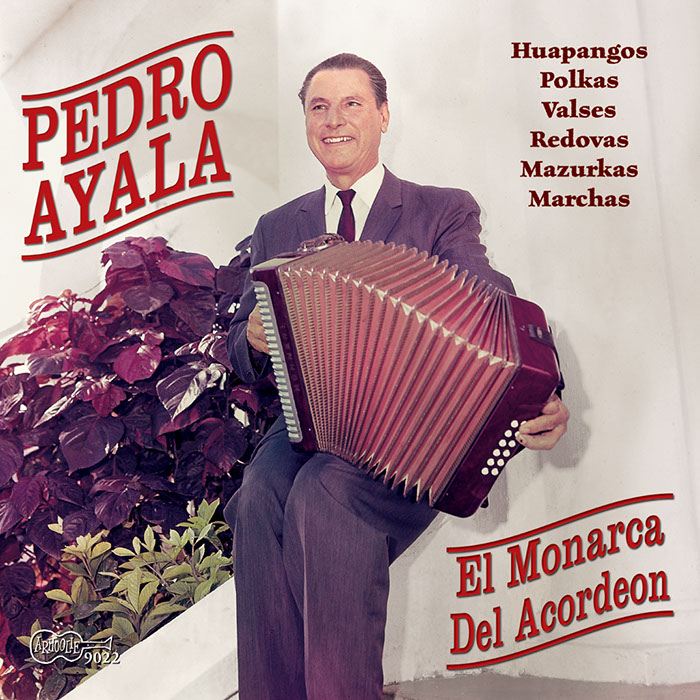

Known as “El Monarca del Acordeon,” Ayala is considered a pivotal figure in the evolution of conjunto music, which arose from working–class communities in south Texas along the Mexican border. Ayala developed a unique playing approach on the button accordion that both borrowed from the past and foreshadowed the future, contributing to a genre that author Manuel Peña called “a collective folk phenomenon.”

“An adequate discussion of the first generation of modern conjunto musicians ought to include the name of Pedro Ayala,” writes Peña in his 1985 study, The Texas-Mexican Conjunto: History of a Working-class Music. “But perhaps more importantly, by 1947, Ayala’s style, more than anyone else’s from his generation, clearly presaged the changes that were about to propel conjunto music into its final stage. Ayala may therefore be considered a transitional artist who shared much with his older contemporaries but who also pointed toward new stylistic trends crystallizing in the late 1940s.”

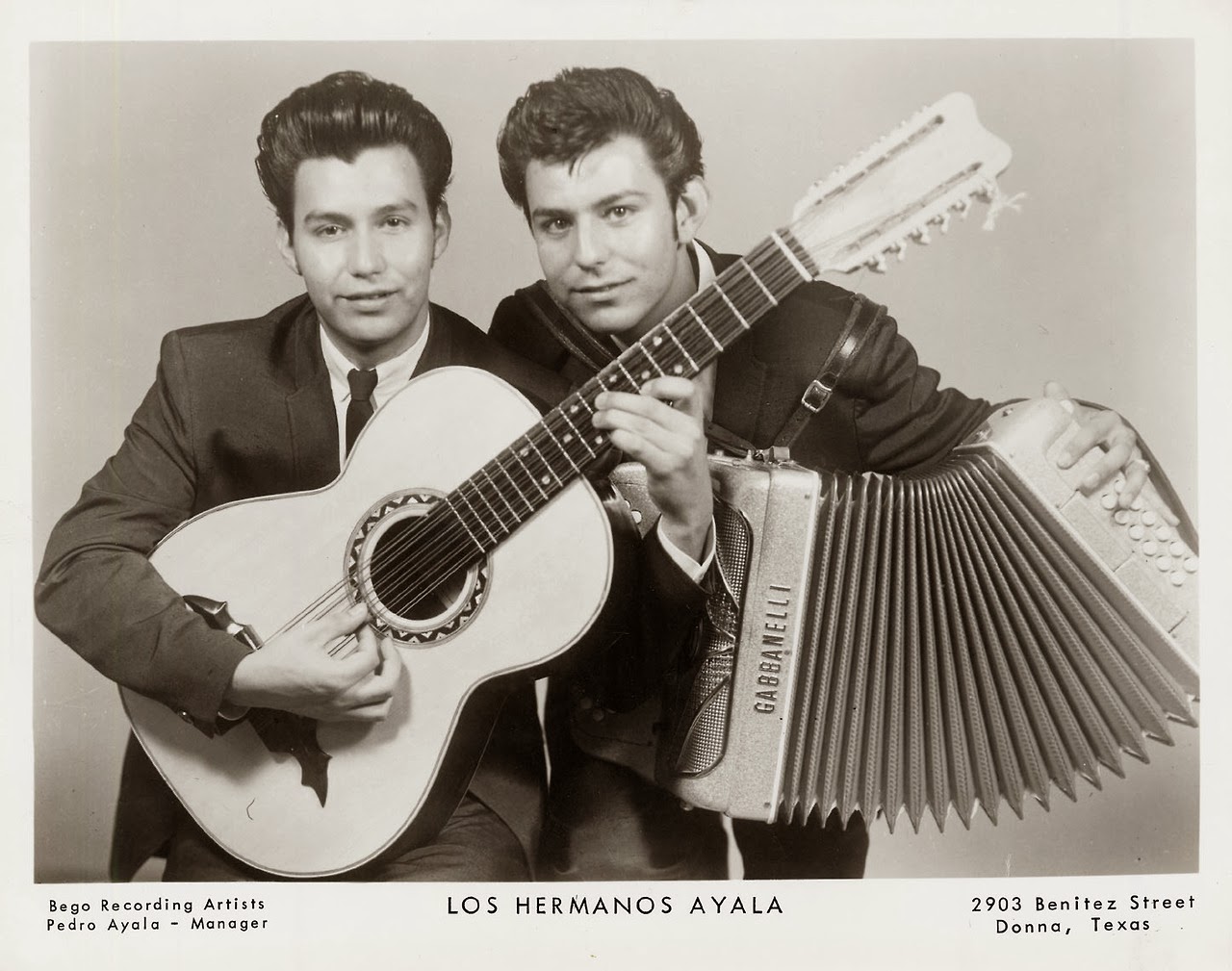

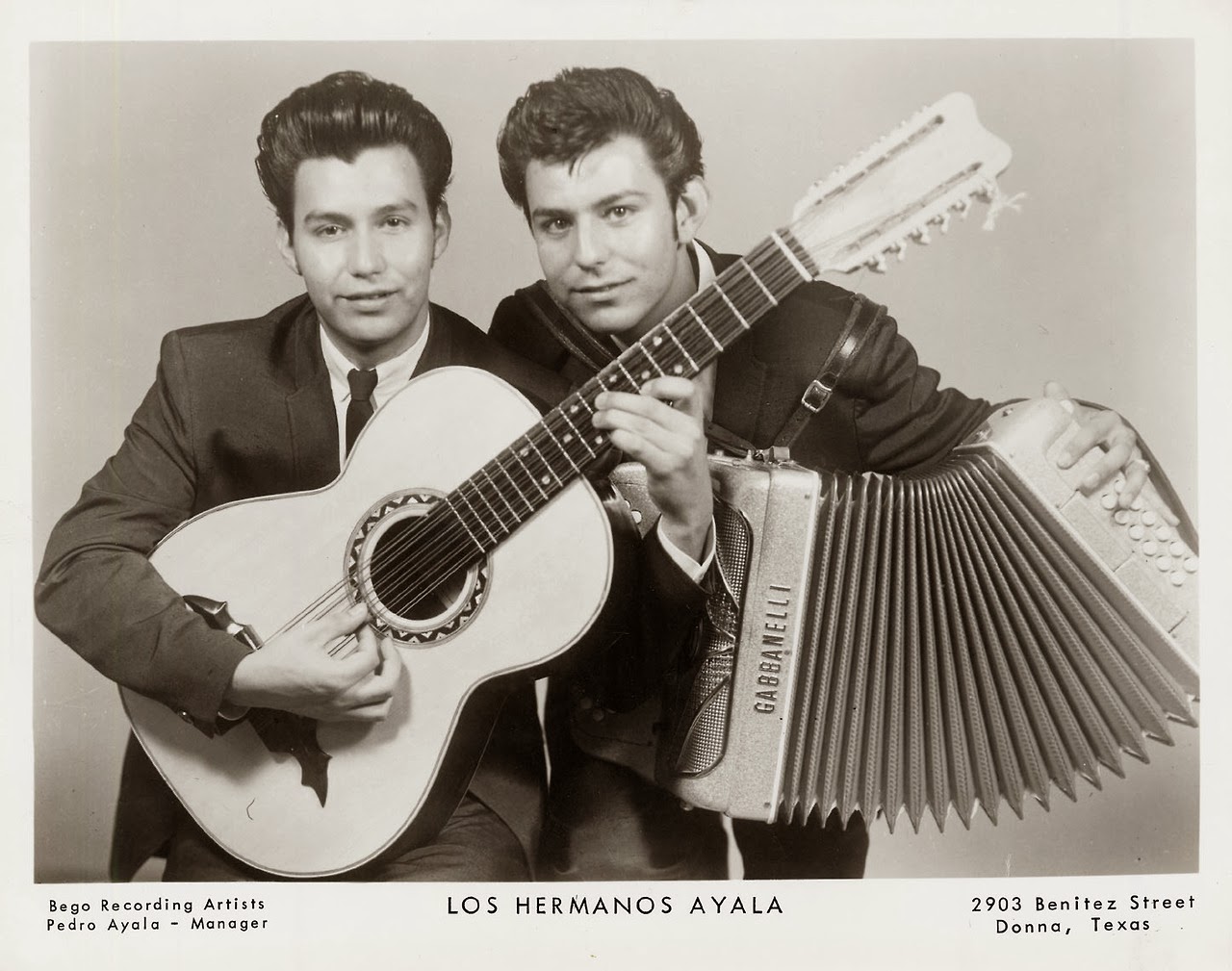

It can also be said that Ayala contributed directly to the next generation of conjunto musicians. His three sons – Ramon, Emilio, and Pedro Jr. – founded an ensemble that carried the family name, Los Hermanos Ayala, popular throughout the Southwest since the 1960s. Pedro Ayala Jr., who passed away in 2007, is being inducted this month into the Texas Conjunto Music Hall of Fame, during the organization’s 17th annual ceremony in San Benito, Texas.

Pedro Ayala Sr. was born on June 29, 1911 in General Terán, Nuevo León, a town immortalized in norteño music, conjunto’s Mexican cousin, as the home base of the famed duet, Los Alegres de Terán. Ayala’s talent was cultivated since childhood in a poor but extraordinarily musical household. His father, Emilio Ayala, was a multi-instrumentalist (accordion, guitar, and clarinet), who at one time played with Los Montañeses del Alamo, another important norteño group from the northern Mexican state of Nuevo Leon. Ayala’s siblings were also musicians, including his brothers Ramiro (guitar, banjo), Santiago (drums), and Francisco (accordion, guitar, clarinet), as well as his sister Felipa (violin).

“He tried his hand at all of the available instruments, apparently becoming rather adept at all of them,” writes Peña, “though, of course, without benefit of formal instruction.”

Ayala also learned to play the tambora, a rustic drum fashioned from goatskin, which his father made for him when he was six. It was the first instrument he played in public, according to Peña, who interviewed the musician for his book. Ayala debuted on the tambora at age 10, backing his father on clarinet at a so-called baile de regalo, a traditional dance at which men offered their partners small gifts of candies, pastries and fruits. Ayala recalls that the drum was so loud it “could be heard for miles on a still night,” and it was later dropped from the standard conjunto lineup because it drowned out the other instruments.

By then, the family had moved to the United States, setting down roots in Donna, Texas, a small border town located between McAllen and Brownsville, with a population of just 1,500 residents at the time. Ayala was eight when they came in 1919, settling in a city with segregated schools for Mexicans, including an entirely separate school for the children of migrant field workers, which included the Ayalas.

The family’s move placed the boy smack in the heart of conjunto country, the Rio Grande Valley.

By 1925, the year Ayala turned 14, he had learned to play the two-row button accordion, the genre’s cornerstone instrument. He was also gaining some early performance experience by playing guitar with Chon Alaniz, one of his favorite accordionists.

But just as Ayala was emerging as a performer in his own right, a family tragedy suspended his musical development. His brother Francisco died unexpectedly in 1928, and the loss devastated their grieving mother, who for a time banned all music from the family home.

It would be three or four years before Ayala could pick up his music career where he left off, according to Peña. By then, he was a young man of 25, and the conjunto music scene of the 1930s was gaining momentum as a regional force.

As Ayala started to make a name for himself as a popular accordionist, he also decided at start a family. On February 3, 1935, he married Esperanza Benitez at St. Joseph's Catholic Church in his hometown. She would remain his wife for life. Wedding guests at the reception danced to the music of Midnight Serenade, a band which featured the groom’s brother-in-law, Jesus Herrera, according to a 2012 profile by journalist and blogger Eduardo Martinez, published in The Monitor, a newspaper based in McAllen, Texas.

The couple had seven children, according to the article which cited interviews with Ayala’s widow and a son. The children are Anita, Elia, Emilio, Maria Magdalena, Maria Olga, Pedro Jr., and Ramon. Wikipedia claims the Ayalas had nine children, but fails to cite a source.

After getting married, Ayala continued to do farm work while cultivating his music career, a double duty which was common among artists at the time. During the mid to late 1930s, he focused on the accordion as his primary instrument, but he also joined Midnight Serenade, his wedding band, as a guitarist, to gain experience with an orchestra. During this time, he also started composing his own songs.

The young musician was still in his 20s when he had his first opportunity to record for an American record company, but it never materialized. The label’s talent scout was actually planning to record another artist, Arnulfo Olivo, who was Ayala’s compadre. When Olivo passed on the offer, he recommended Ayala as a substitute, but the label declined and recorded neither.

It would be another decade before Ayala would make his first recordings.

So while Ayala’s contemporaries steadily built their discographies during the 1930s and 1940s, Ayala continued to perform live throughout the Rio Grande Valley. According to Peña, he appeared mostly at so-called bailes de negocio, or taxi dances, where men paid women for a dance on makeshift platforms set up outside of cantinas, a popular practice in rural communities.

So while Ayala’s contemporaries steadily built their discographies during the 1930s and 1940s, Ayala continued to perform live throughout the Rio Grande Valley. According to Peña, he appeared mostly at so-called bailes de negocio, or taxi dances, where men paid women for a dance on makeshift platforms set up outside of cantinas, a popular practice in rural communities.

While he would come to influence the next generation of conjunto musicians, Ayala admits that he was strongly influenced at first by his peers, freely imitating other players, such as Martinez.

“We all began to copy Narciso,” Ayala is quoted as saying in Peña’s 1999 book, Música Tejana: The Cultural Economy of Artistic Transformation. “He started to record first, and I used to play the tunes he recorded, just like he had recorded them.”

Ayala made his first recordings in 1947 for Mira Records, a fledgling label based in McAllen that would soon become a powerhouse in the field. The label was founded by local entrepreneur Arnaldo Ramirez, who soon changed the name to Discos Falcon, creating a brand that became synonymous with conjunto music and Tex-Mex culture.

Ayala’s first recordings for Mira were two polkas, “La Burrita” and “La Pajarera.” The label executive dubbed the act Pedro Ayala y su Conjunto del Rio. Before the end of the decade, Ayala recorded several other notable songs, including "El Naranjal," inspired by a major freeze that destroyed Texas orange crops in the winter of 1948. Ayala made the record with the orchestra of a cousin, Eugenio Gutierrez, marking the first time the button accordion was featured in an orchestral setting, according to The Monitor article.

"Back then the accordion was not appreciated much, it was kind of considered a low-level instrument," Ayala’s son Emilio told the paper. “That would worry him very much, so little by little, he started raising the value of the accordion."

It was Falcon’s founder who gave Ayala the nickname that would stick through his entire career: "El Monarca del Acordeon." Ramirez also made Ayala the label’s house accordionist, recording studio sessions with a host of regional stars, including Lydia Mendoza, Luis Pérez Meza, Luis Aguilar, and many others.

In his own recordings, Ayala added the tololoche, or contrabass, to the instrumental lineup. He was not the first to do so, explains Peña; Santiago Jimenez had added the instrument years earlier, but the novelty didn’t stick at that time because other musicians failed to follow suit. After Ayala re-introduced the instrument in his earliest recordings, Peña says, it “rapidly took hold,” creating what was to become the core of the modern conjunto ensemble: accordion, bajo sexto, and tololoche.

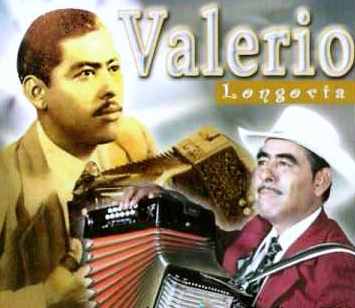

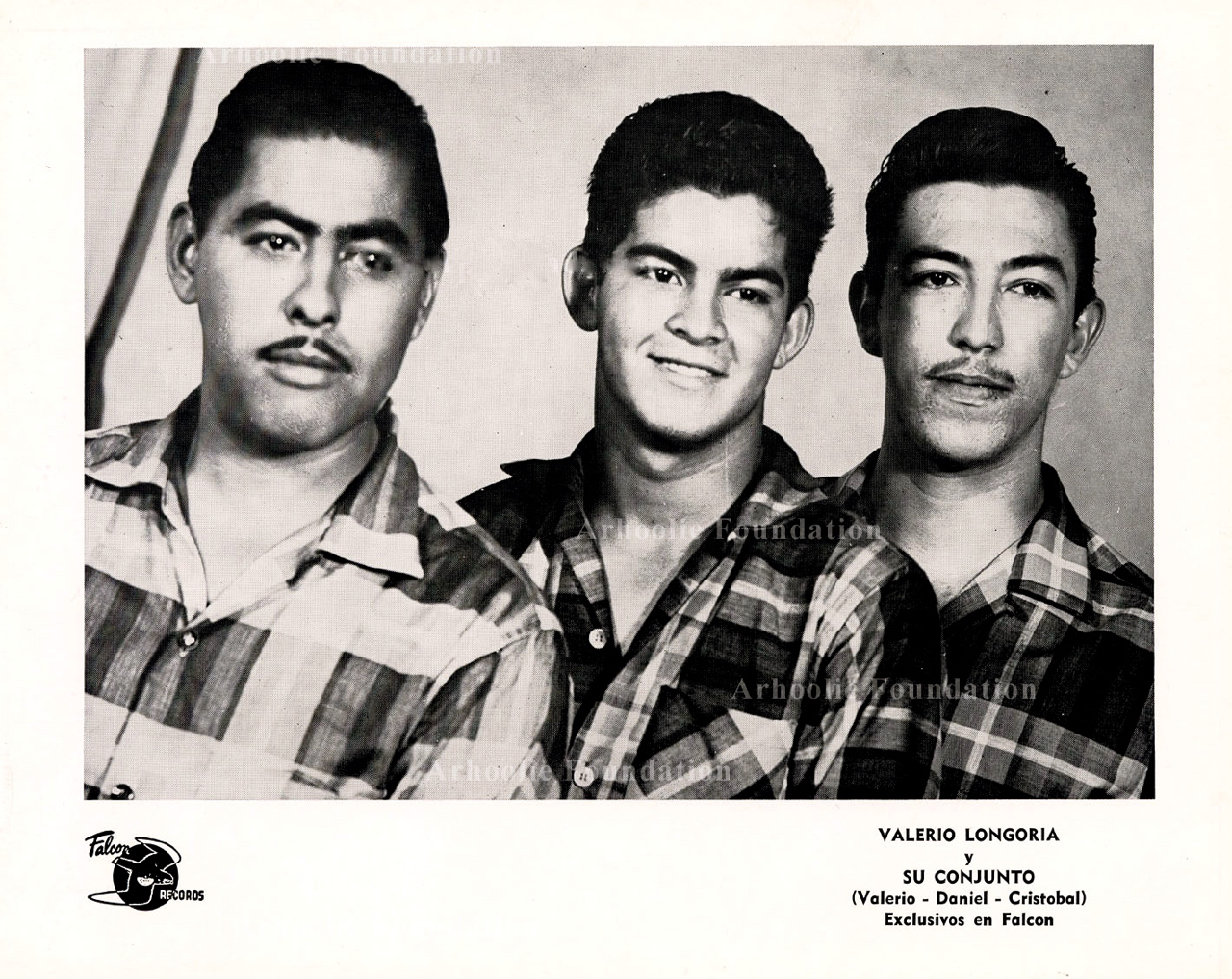

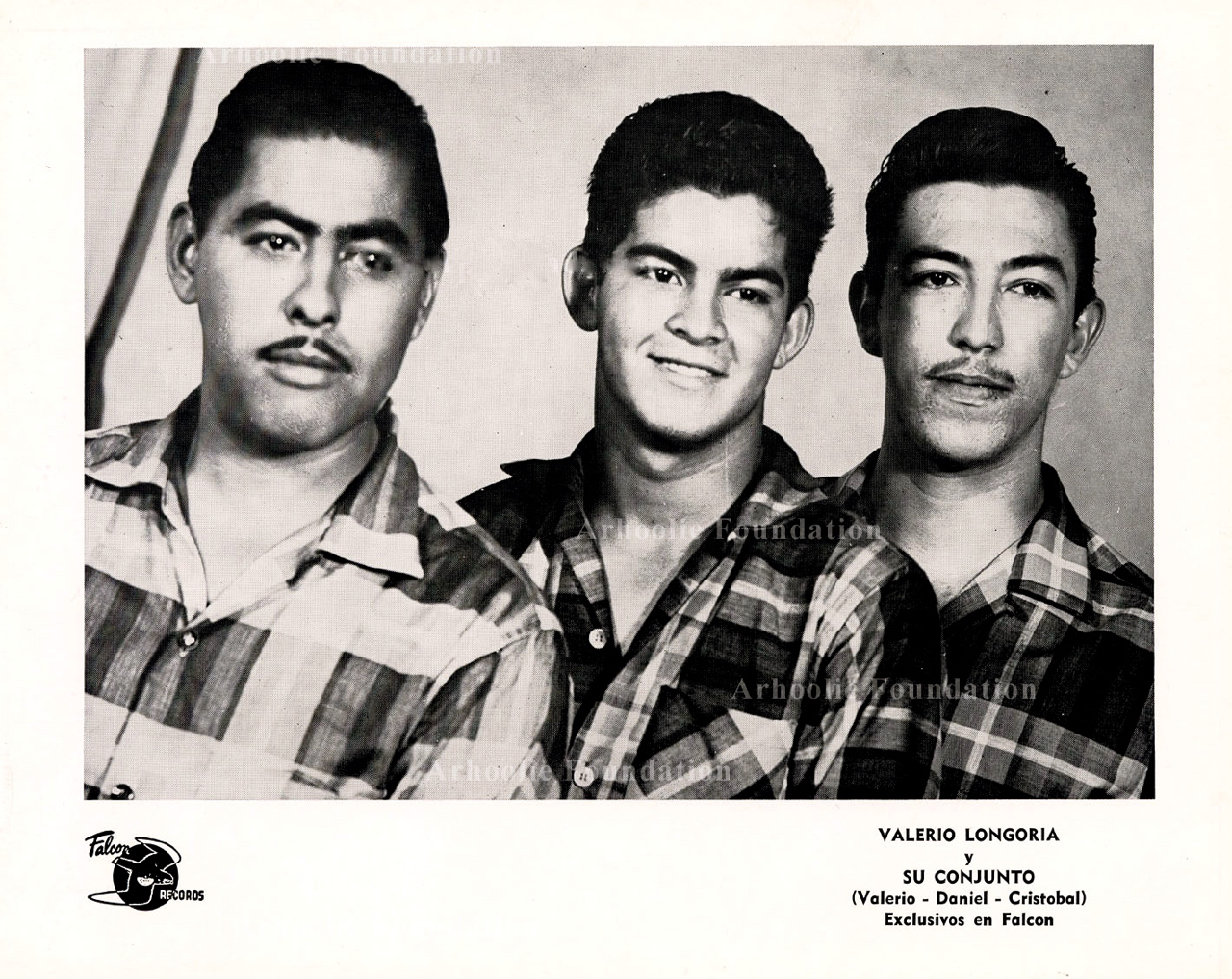

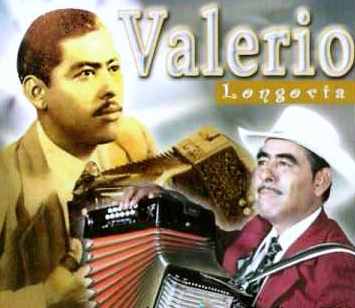

Peña describes Ayala’s accordion technique as “snappy,” with “his polkas featuring fast sixteenth note fingerings,” in the style of Martinez. But Ayala exhibited a more marcato style, forcefully emphasizing certain notes, a technique that would influence younger players, such as Tony de la Rosa and Valerio Longoria, who would soon gain fame in the field.

“Pedro Ayala’s recordings of the late 1940s bring the curtain down on the first scene of conjunto’s stylistic development,” writes Peña. “Rigidly taking their cue from the older musicians, particularly Martinez and Ayala, the younger performers soon begin to forge their own conception of what conjunto should strive for musically.”

Throughout the 1950s and ’60s, Ayala went on to record dozens of tracks for regional labels, including Bego, Falcón, Ideal, Bernal, Discolando, RyN, Pato and Oro. He also continued to tour extensively, performing at marathon dances that would last from dusk to dawn. And he composed many popular songs in a variety of styles, including valses, polkas, and redovas.

Ayala began his recording career comparatively late, at the end of the 78-rpm era, but he went on to make several albums in the new Long Play format introduced in the 1950s. His LPs included “Viva Mi Desgracia” (1968) and “Adios Mama Carlota” (1973).

In 1959, Ayala and his family hit the migrant trail again, picking cherries in Michigan and grapes in California. Wherever they went, Ayala would play at local dances. And he wasn’t alone. His widow recalls working the fields around Shelby, Michigan, alongside other conjunto stars of the stature of Valerio Longoria and Tony De La Rosa.

Ayala’s sons followed their father’s footsteps as conjunto musicians during the 1950s, starting with Pedro Jr. on accordion and Ramon on bajo sexto, joined later by their younger brother Emilio on electric bass, which had mostly replaced the tololoche in modern conjunto ensembles. Billed as Los Hermanos Ayala, the brothers made their first recording in 1959 for Bronco Records, a subsidiary of Falcón. They recorded and toured with their father, as well as an independent act, playing together for half a century until Pedro Jr.’s death at age 62.

On a personal level, the elder Ayala was admired for his forthright manner and his honesty, according to The Monitor. He once compensated a promoter for arriving late to a show, due to car troubles, by returning part of his pay, his son Emilio recalled. And he was known for helping fellow musicians repair their accordions, a skill he had learned from his father.

Pedro Ayala Sr. passed away on December 1, 1990. He was 79.

His widow recalled the qualities of her late husband when she was interviewed for The Monitor in 2012.

"He lived such a happy life, always had a smile on his face and would always treat everyone with respect and help them out in any way he could," said Esperanza, who was 90 at the time. "Those were such beautiful times."

In 1988, Ayala received a National Heritage Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts, one of the nation’s highest honors in traditional arts. On that occasion, he performed at a concert in the nation’s capital.

Arhoolie Records released a compilation of his recordings in 2001, titled El Monarca del Acordeon, now available through Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

– Agustín Gurza

Blog Category

Tags

Images