Artist Biography: Los Donneños, Norteño Pioneers

Los Donneños, a duet formed in the late 1940s in the Rio Grande Valley of South Texas, were pioneers in the evolution of norteño music during the 1950s. They went on to become one of the first Tex-Mex acts to find major success on both sides of the border.

Los Donneños, a duet formed in the late 1940s in the Rio Grande Valley of South Texas, were pioneers in the evolution of norteño music during the 1950s. They went on to become one of the first Tex-Mex acts to find major success on both sides of the border.

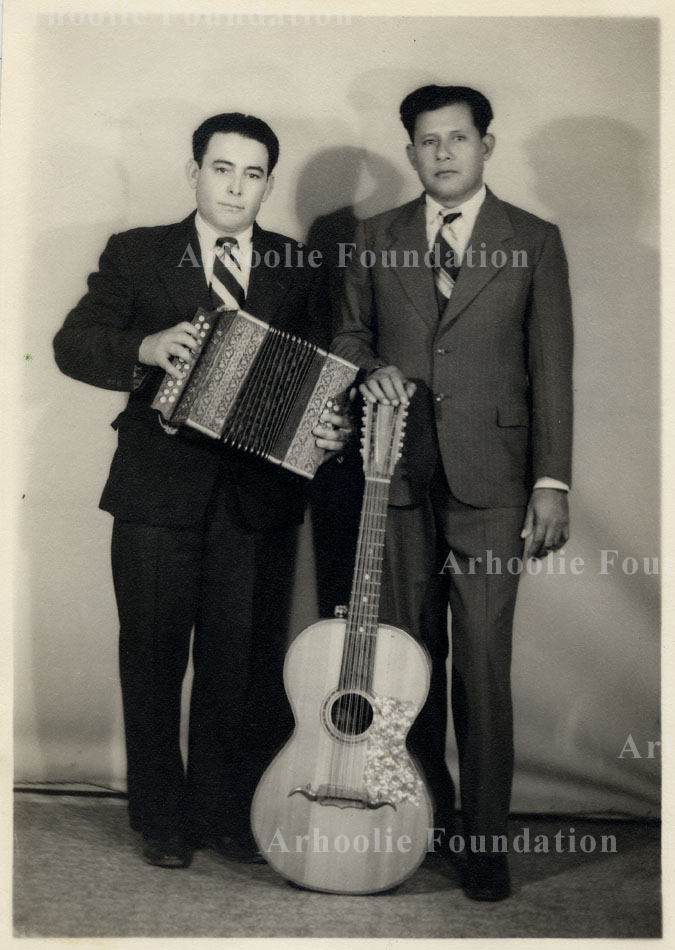

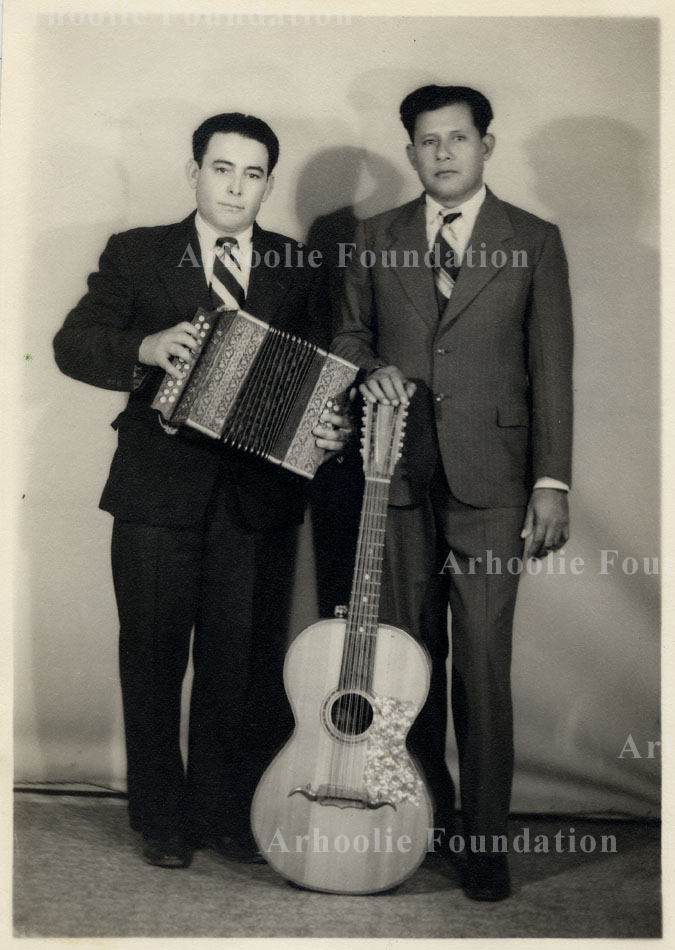

The historic duet was formed by two musicians, Ramiro Cavazos on guitar and Mario Montes on accordion. They both hailed from the Mexican border state of Nuevo Leon, but they met only after moving to the U.S. side of the Rio Grande.

Cavazos was born in 1927 in Garza Ayala, a rural community on the road between Monterrey, Mexico, and Laredo, Texas. Montes was born four years earlier in General Terán, southwest of Monterrey, home to another famed norteño group from the same period, Los Alegres de Terán, Tomás Ortiz and Eugenio Abrego. In fact, in the early years of both acts, Cavazos performed with Los Alegres and actually recorded with them on several 78s for the Orfeo label, billing themselves as Ortiz y Cavazos con el Dueto Abrego.

Cavazos and Montes immigrated separately to the United States and met in the sleepy town of Donna, Texas, named after the daughter of an early frontier developer, Thomas Jefferson Hooks. When they arrived in the late 1940s, the town of some 5,000 residents still had schools with three tiers of segregation: whites, Mexicans, and migrants.

In Donna, both musicians held day jobs while pursuing their passion for music—Montes picking fruit in the fields and Cavazos washing dishes at a small restaurant for $14 a week.

More than 60 years later, Cavazos still fondly recalled the first time he met his future partner, as he told journalist Eduardo Martinez in a 2012 interview published by The Monitor of McAllen, Texas. He said he was riding his bicycle one day when he saw two men playing music on the street. When Cavazos approached, one of the men, who turned out to be Montes, asked if he was a musician. Yes, Cavazos said, he played the guitar and sang. That’s all it took to strike up a lifelong musical partnership.

Cavazos and Montes made their first recordings in 1947 for Discos Falcon, based in McAllen. According to an article in El Extra, a news website in South Texas, the initial tracks were “Ojos Negros Nunca Engañan” (Dark Eyes Never Lie) and “El Corrido De Bernabé Mata,” released on 78-rpm disc the following year. However, the Frontera Collection has a different song on the flip side of the duo’s debut disc – “Así Se Baila en Reynosa” (This is How They Dance in Reynosa). The aforementioned corrido is cited incorrectly; it’s actually titled “Bernardo Mata” and is a popular ballad that appears in the Frontera archive by a dozen different artists. In the database, recordings of the corrido by Los Donneños include a 45-rpm single and an album track on a greatest-hits compilation, both on Falcon’s Bronco imprint.

The group’s early recordings featured Cavazos on guitar rather than the traditional bajo sexto. But he would soon take up the 12-string guitar commonly used in conjunto music because he said it had a stronger and more appealing sound. He won acclaim for his style on the instrument, which played bass lines against the accordion in these early duets.

Following that first recording session, Falcon label owner Arnaldo Ramirez dubbed the new act Los Donneños, based on the fact that they were residing in Donna. The artists were perplexed, however, because they were actually from Mexico and had just recently moved to their namesake city, and didn’t stay there long. But the name stuck, as if they were native sons.

Still, their partnership remained fluid in the early days.

Montes soon married a U.S. citizen and legalized his status. Meanwhile, Cavazos, who remained undocumented until 1954, would spend time across the border in Reynosa, Tamaulipas. There, just across the river from McAllen, he played guitar with Los Alegres, performed constantly, and made good money. The musician recalled that heady time in an interview with Frontera Collection founder Chris Strachwitz, who wrote liner notes for a 2006 retrospective album, Los Donneños: Grabaciones Originales/Historic First Recordings, 1950-1954 (Arhoolie 9057).

Montes soon married a U.S. citizen and legalized his status. Meanwhile, Cavazos, who remained undocumented until 1954, would spend time across the border in Reynosa, Tamaulipas. There, just across the river from McAllen, he played guitar with Los Alegres, performed constantly, and made good money. The musician recalled that heady time in an interview with Frontera Collection founder Chris Strachwitz, who wrote liner notes for a 2006 retrospective album, Los Donneños: Grabaciones Originales/Historic First Recordings, 1950-1954 (Arhoolie 9057).

“Around 1950, Ramiro made more records with Tomas Ortiz for the Orfeo label but earned his living playing weddings, quinceafieras, and on weekends in the cantinas,” Strachwitz wrote. “Ramiro said that in those beer joints there was plenty of money to be made from the Braceros who had come back from the cotton fields of Texas and wouldn't let the musicians go until two or three in the morning. They charged three Mexican pesos per song and made about 40 or 50 pesos each per night, with which he says you could live like a king!”

Later in the 1950s, Cavazos and Montes appeared in five films along with the colorful norteño singer and movie star Lalo Gonzalez, a.k.a. "El Piporro." In this clip from the 1959 film Dos Corazones y un Cielo, the duo expertly accompanies the showy star on the comically flirtatious ditty, “Las Quedadas” (The Spinsters). Piporro also took Los Donneños on tour as his backup group throughout the United States, Venezuela, and Cuba, boosting their popularity internationally.

Later in the 1950s, Cavazos and Montes appeared in five films along with the colorful norteño singer and movie star Lalo Gonzalez, a.k.a. "El Piporro." In this clip from the 1959 film Dos Corazones y un Cielo, the duo expertly accompanies the showy star on the comically flirtatious ditty, “Las Quedadas” (The Spinsters). Piporro also took Los Donneños on tour as his backup group throughout the United States, Venezuela, and Cuba, boosting their popularity internationally.

When their Falcon recording contract expired in 1954, the duo went looking for better deals, as Strachwitz notes. They first jumped to Discos Torero, a Corpus Christi label owned by Genaro Tamez. Frontera has 32 of those tracks, all 78- or 45-rpm singles, on Torero, whose slogan was “Cada Disco, Dos Exitos.”

By the time the duo returned to Mexico in 1957, they had signed a new contract with Columbia Records, recruited by the label’s renowned artistic director Felipe Valdez Leal. They remained on the Columbia roster for the next 17 years, defying the presumption that Mexico City labels were not interested in promoting “low-class” conjunto music from across the border.

More than 140 of those Columbia sides, mostly 45-rpm singles, are featured in the Frontera Collection. They include a newer version of the corrido of “Bernardo Mata” with improved sound quality that is especially noticeable on the vocal harmonies. In all, the archive holds a total of 373 tracks by Los Donneños on some 20 labels, with Cavazos credited as composer on dozens of tunes.

In 1962, their wide popularity was confirmed with their triumph at a national competition involving more than 85 musical acts, held in Ciudad Victoria, Tamaulipas. Los Donneños walked away as Campeones Nacionales de la Musica Norteña, the recognized leaders in their field. The win gave them the nickname of champions: “Los Campeonísimos Donneños.”

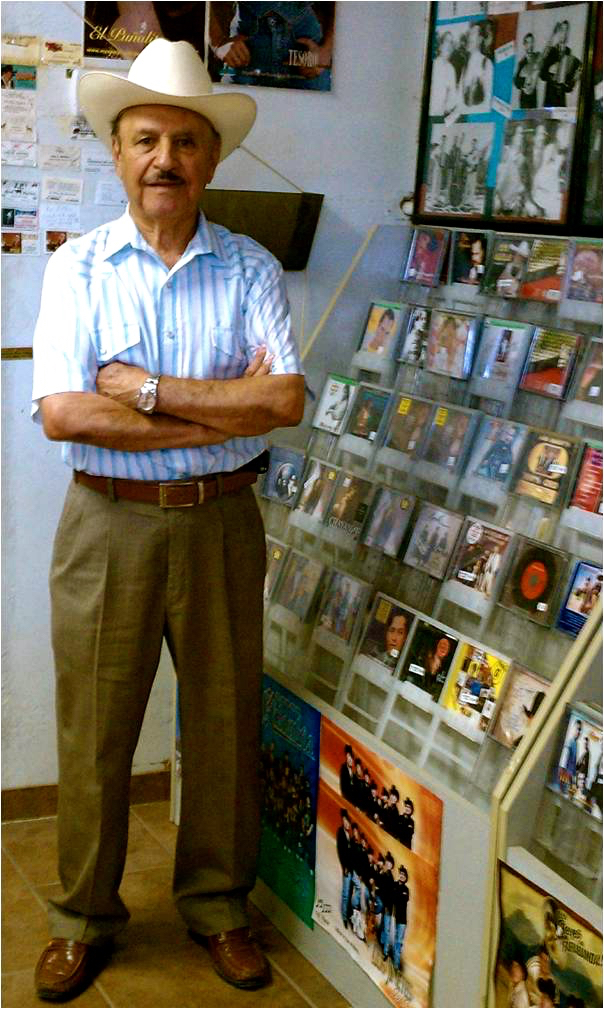

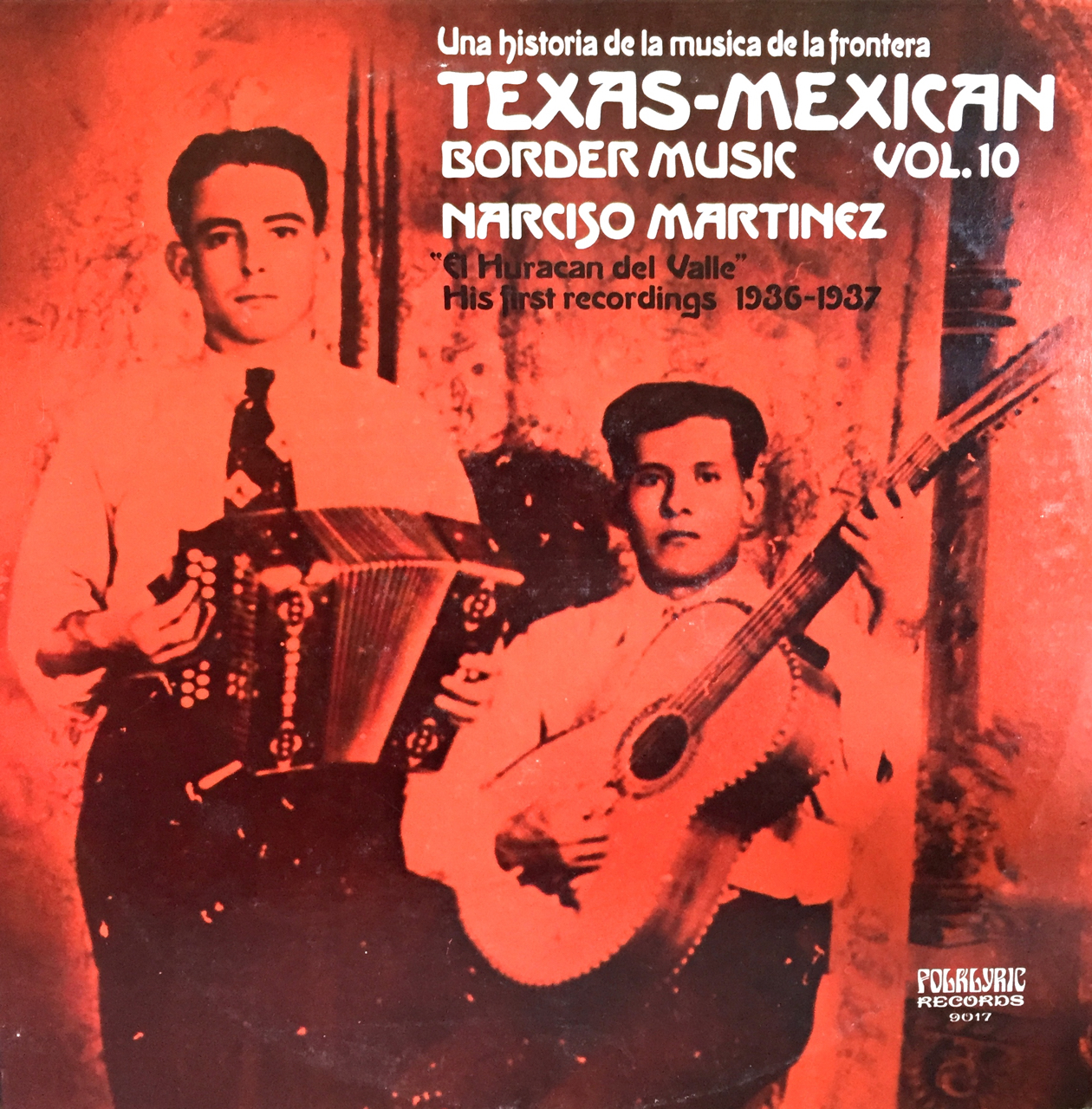

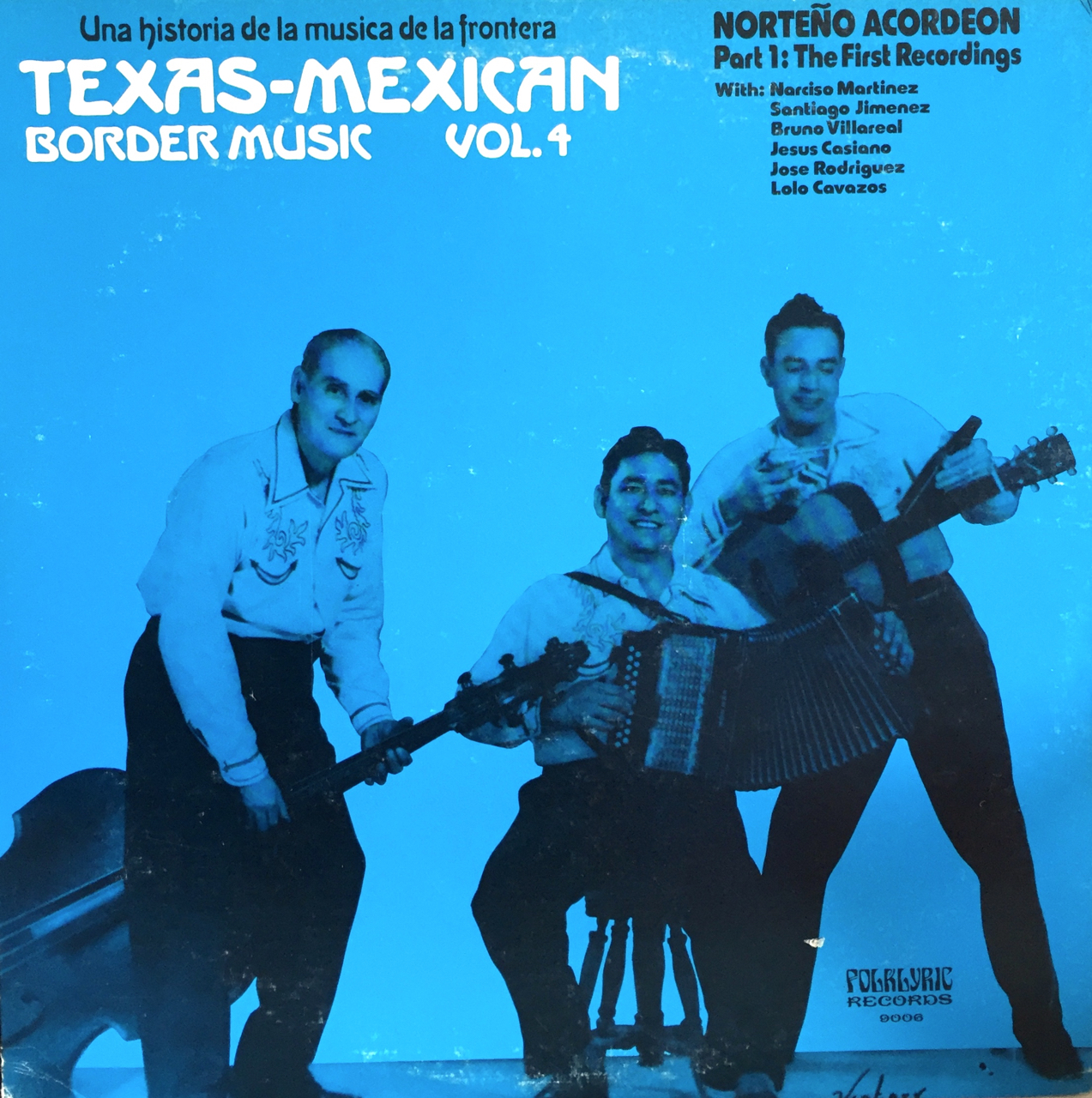

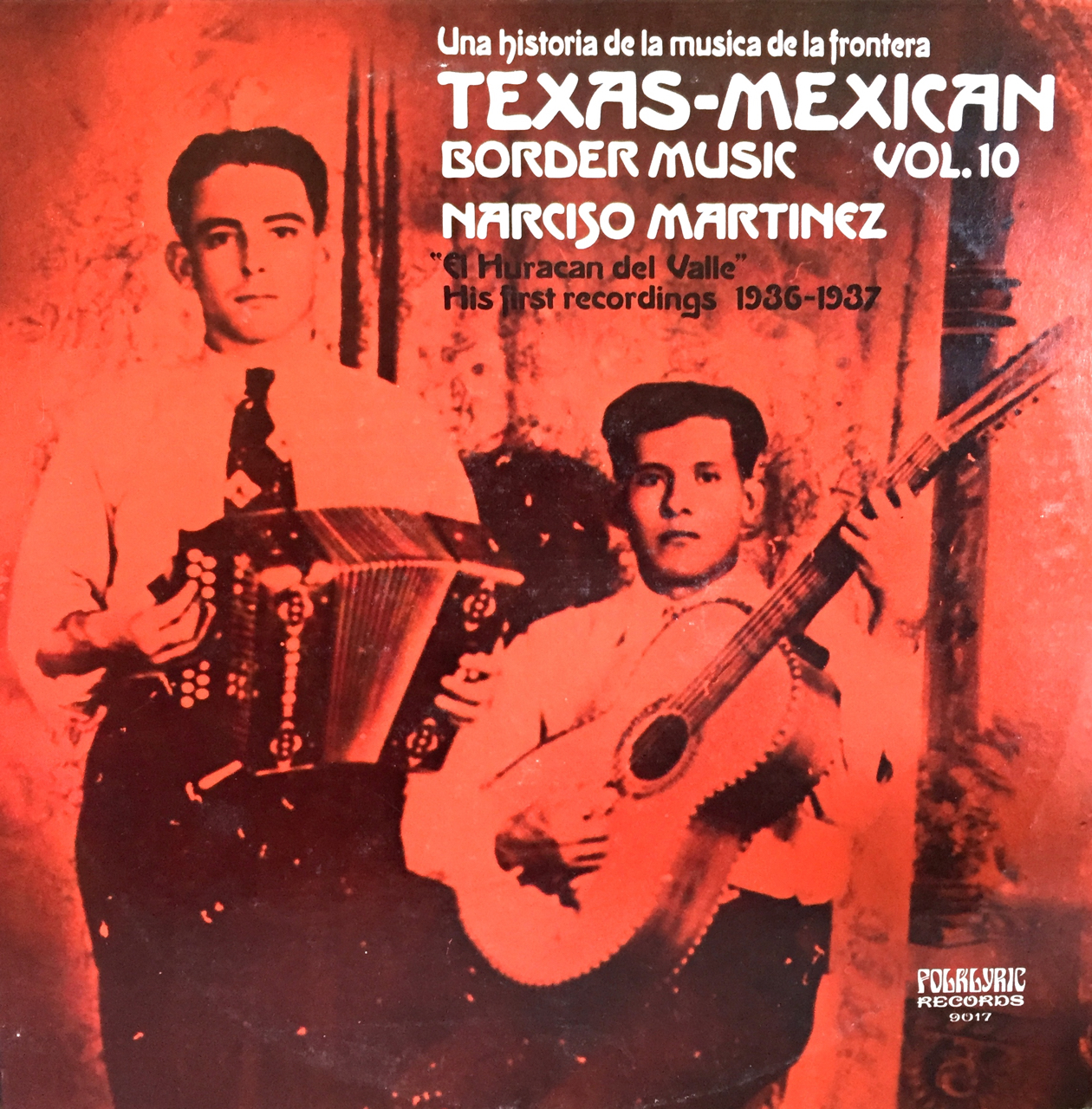

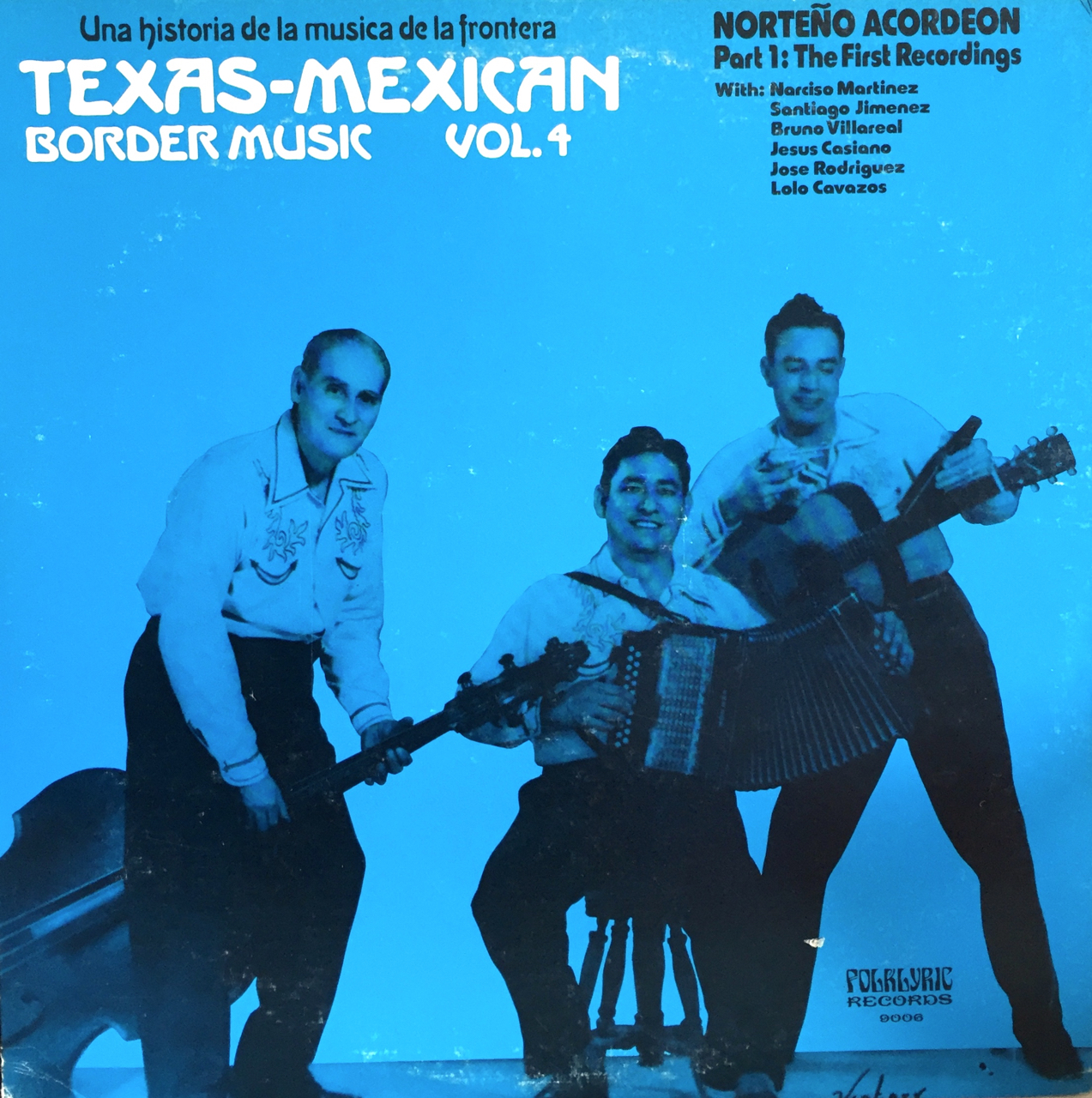

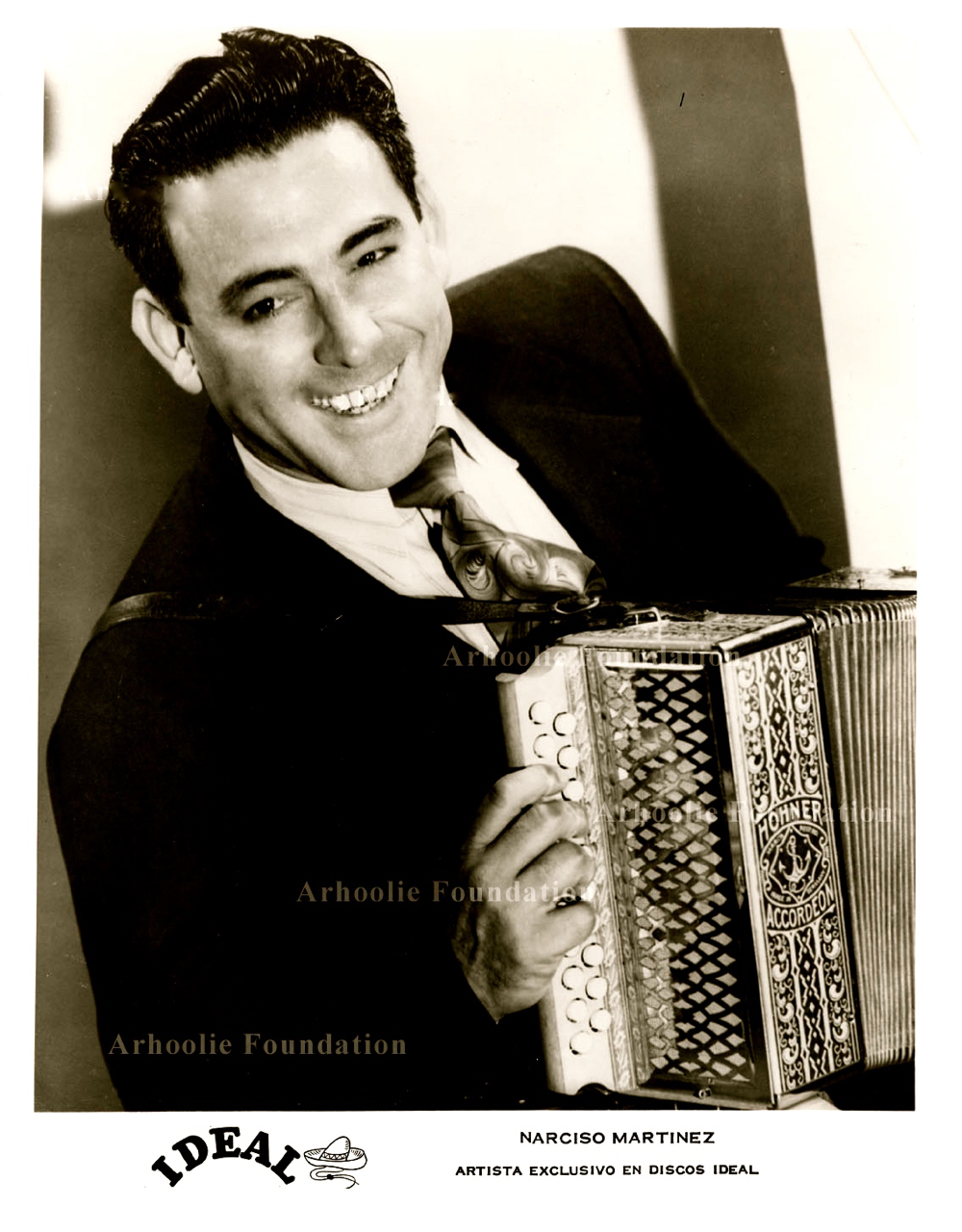

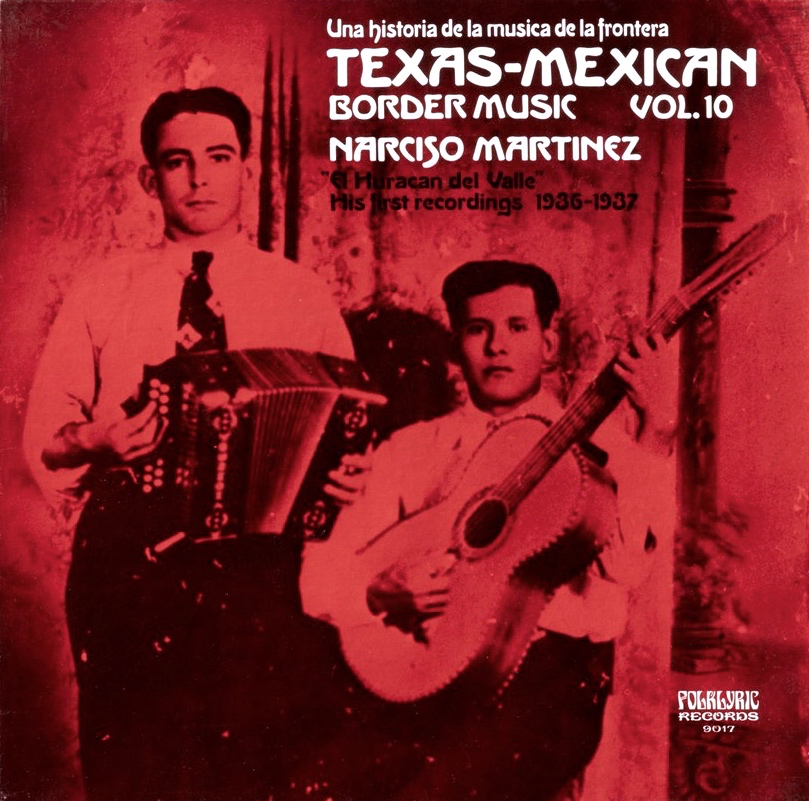

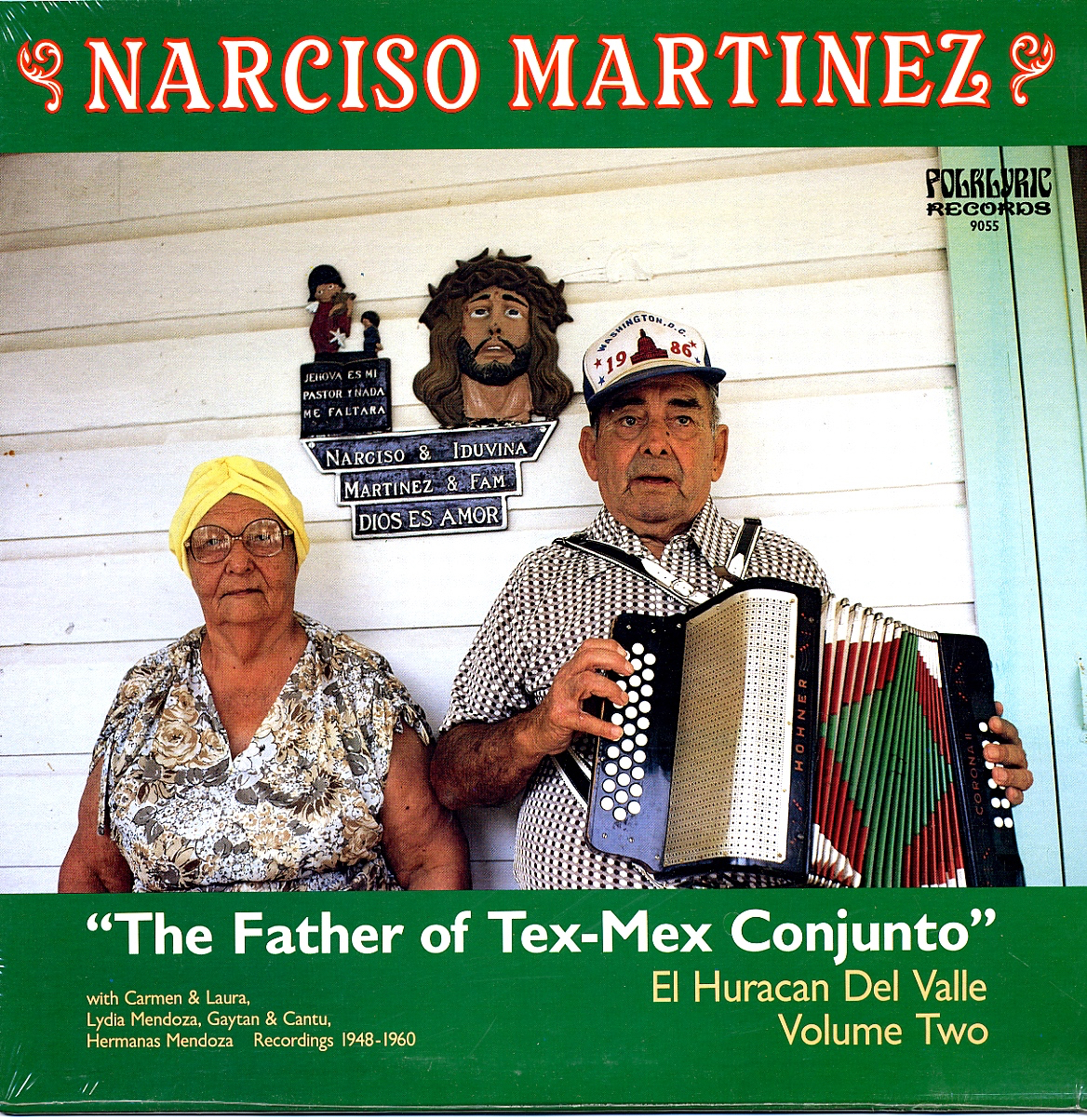

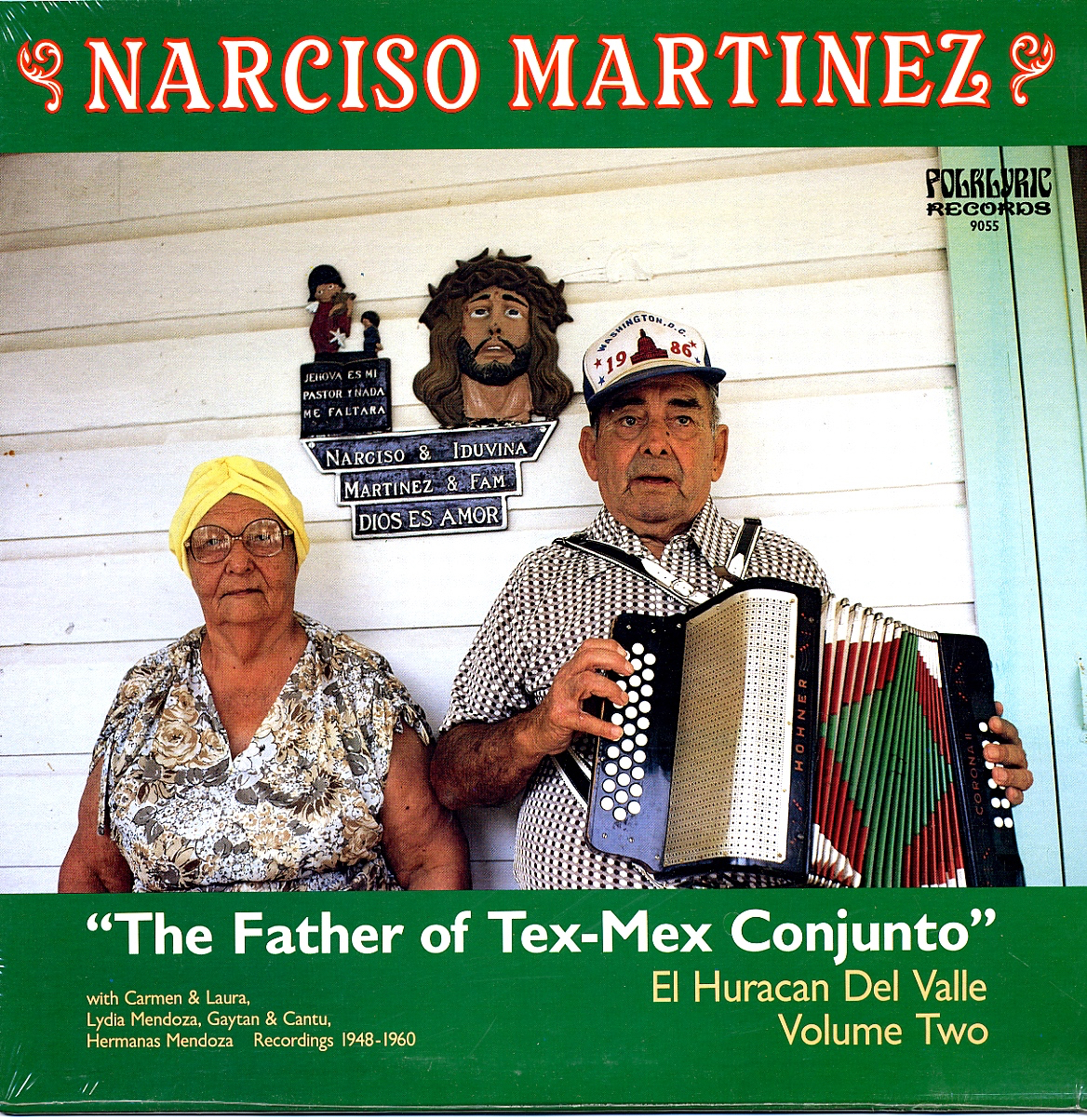

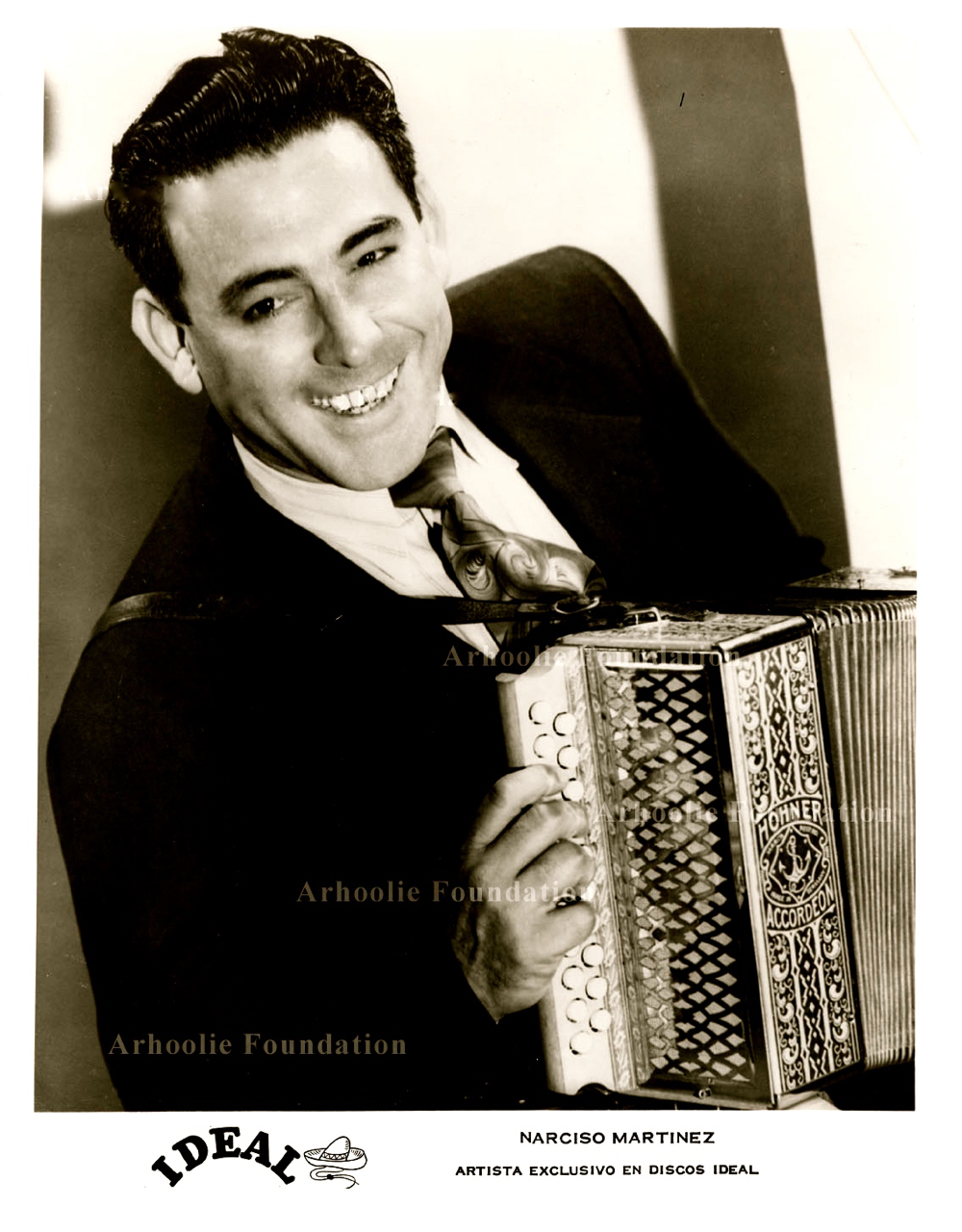

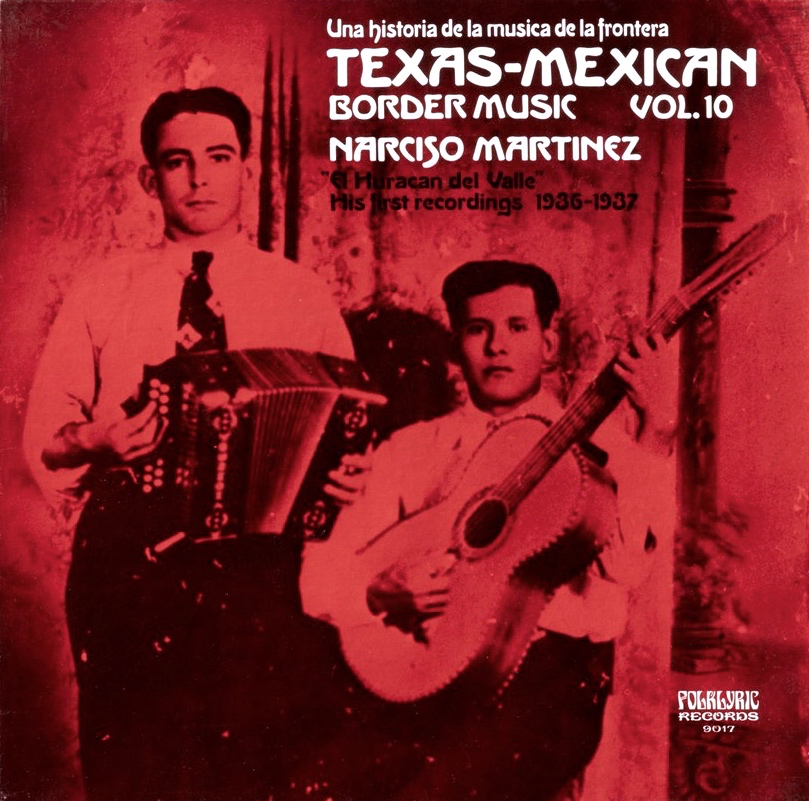

By the mid ’70s, the duo had returned permanently to the United States. Cavazos opened his own record label, Discos RyN, and a retail music store in downtown McAllen. His store became a cultural hub in the area, and the label recorded many important artists from the Rio Grande Valley, including Narciso Martinez, Conjunto Tamaulipas, Beto Quintanilla, and Ruben Vela. Sealing the band's cross-border ties, Montes married Alma de la Garza on February 25, 1951, their union officiated by the Justice of the Peace of Donna, Texas. Their daughter Diana later married famed Tejano saxophonist and bandleader Roberto Pulido, and their children, Bobby and Alma Pulido, also went on to build separate Tejano music careers of their own.

In 1976, Cavazos appeared with Conjunto Tamaulipas in the Les Blank/Chris Strachwitz documentary Chulas Fronteras, the seminal documentary on conjunto and norteño music. The film opens with Cavazos delivering a classic interpretation of “Canción Mixteca,” the nostalgic song of immigrant yearning for the homeland.

In 1976, Cavazos appeared with Conjunto Tamaulipas in the Les Blank/Chris Strachwitz documentary Chulas Fronteras, the seminal documentary on conjunto and norteño music. The film opens with Cavazos delivering a classic interpretation of “Canción Mixteca,” the nostalgic song of immigrant yearning for the homeland.

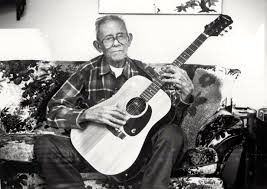

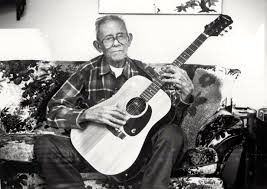

After Mario Montes passed away on January 28, 1993, Cavazos went on to perform with other outstanding accordionists, including Rene Maciel, Juan Antonio Coronado, and Beto Espinosa, in various incarnations of Los Donneños. In 2007, at age 80, he was inducted into the Texas Conjunto Music Hall of Fame.

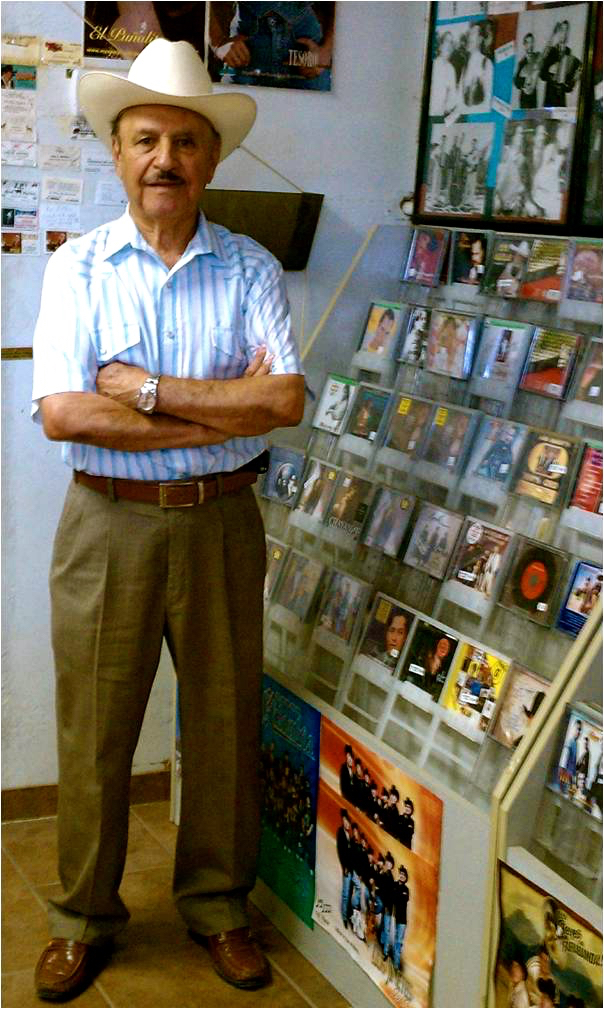

For the next decade, the octogenarian could still be found behind the counter at his record store on South 23rd Street in McAllen. And he continued to perform.

In 2010, Cavazos participated in a recording that brought together other veteran stars of the norteño genre, including Hector Montemayor, Lorenzo de Monteclaro, and Poncho Villagomez, calling themselves Los Amigos Desde el Rancho. The CD, entitled La Antología de La Música Norteña, features Cavazos on his own composition, “Enseñate a Perder (Learn to Lose).” The studio recording was followed by a live performance on a separate disc, Los Amigos del Rancho, Vol. 2, Live At Allende Nuevo León. It includes another Cavazos composition, looking at heartbreak from the losing side, “Enseñame a Perder” (Show Me How to Lose).

On February 16, 2019, Cavazos celebrated his 92nd birthday with a backyard concert, captured in a homemade video posted to the band’s Facebook page. In the clip, he performs one of Los Donneños’ most famous songs, “Mataron a la Paloma,” which Cavazos co-wrote with Basilio Villiareal, “their old compadre,” as Strachwitz calls him. The tune is a tongue-in-cheek torch song about a heartbroken man who sends a message to his lost love via messenger pigeon; tragically, the bird is killed before completing is mission, so the woman never learns that the man is sorry and wants her back. In the song, he says he’ll never forgive himself for trying to save himself a stamp with mail service being as good as it is.

Mataron a la paloma que te llevaba el recado,

Por eso siempre pensaste que yo te había abandonado.

El recado se quedó en el pico de una loma,

Allí prietita querida, mataron a la paloma.

Por eso aunque pase el tiempo no me podré perdonar,

Que habiendo tan buen correo, con quién te lo fui a mandar.

En él te contaba todo, pidiendo que regresarás,

Que perdonarás mis faltas y conmigo te casarás.

Por eso aunque pase el tiempo no me podré perdonar,

Que habiendo tan buen correo con quién te lo fui a mandar.

Por ahorrarme una estampilla, maldita estampa, la mía!

“Ramiro Cavazos is an icon and a legend in his own style that only he can produce," Lupe Saenz, president of the South Texas Conjunto Association, told The Monitor. “His compositions are constantly being recorded by conjuntos because they know that his songs are quality compositions. Composers like Mr. Cavazos are few and far between.”

– Agustín Gurza

Blog Category

Tags

Images