The Eternal Bolero, Part 2: Songs I Learned in College

In the first installment of my three-part series on the bolero, I offered an overview of the romantic genre and highlighted songs I had learned from my parents as a child. In Part 2, I’ve selected eight more classics that I discovered during my college years in the late 1960s and early ‘70s.

In the first installment of my three-part series on the bolero, I offered an overview of the romantic genre and highlighted songs I had learned from my parents as a child. In Part 2, I’ve selected eight more classics that I discovered during my college years in the late 1960s and early ‘70s.

Those were years of cultural upheaval and explosive creativity, especially in pop music. For ethnic minorities fighting for civil rights and racial respect, it was an exciting time of cultural discovery. Many young Mexican Americans, swept up in the Chicano Movement, made it their mission to explore and affirm their cultural roots in food, literature, art, and music.

That reawakening sparked a wave of community-based arts among Latinos/as, producing influential clusters of new music that put Latinos on the national pop music map.

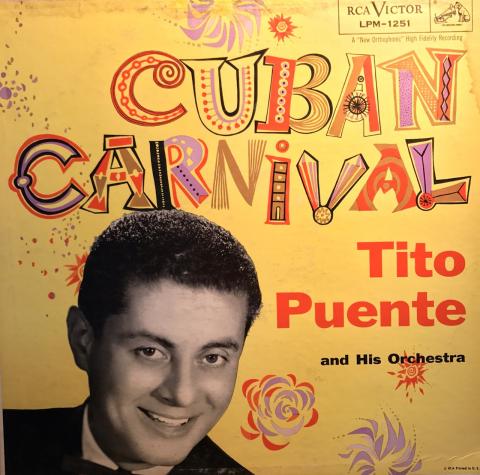

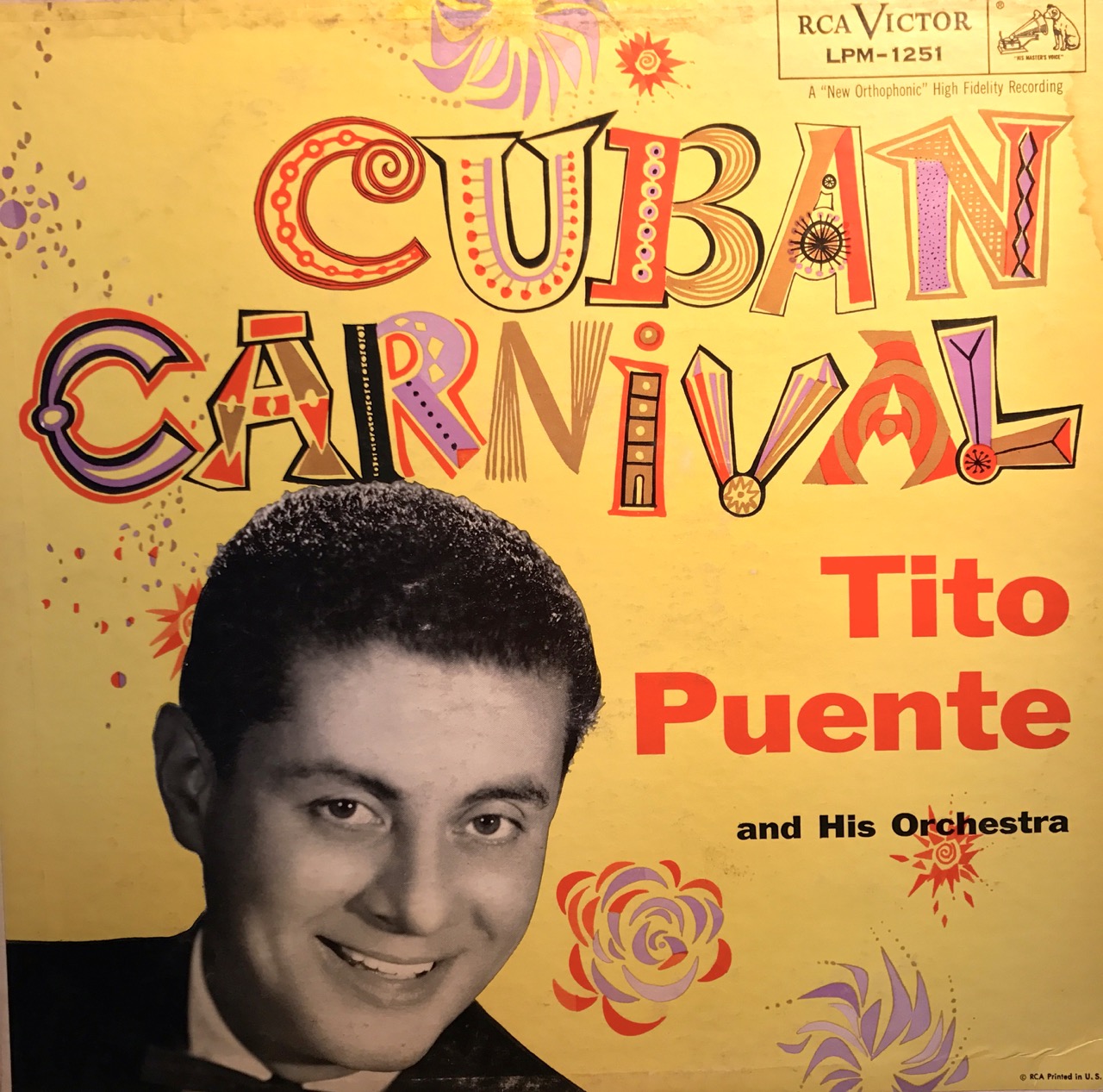

In Texas, Little Joe and other Tejanos pioneered the Tex-Mex sound. In San Francisco, Carlos Santana, the son of a mariachi musician from Tijuana, kicked off the Latin Rock craze by incorporating Tito Puente’s “Oye Como Va” into a brash new rock/tropical fusion. And in Los Angeles, Los Lobos spearheaded Chicano rock, and Tierra forged the East L.A. sound.

Meanwhile on the East Coast, the children of Puerto Rican and Cuban immigrants fueled an exciting new era of Caribbean dance music dubbed salsa, featuring a hip style, jazzy elements, and modern recording techniques.

I was a huge fan of the salsa music coming out of New York at the time. It felt a little like the so-called British Invasion of the previous decade, with U.S. fans hungry for the latest releases from London. The salsa craze set us on a similar hunt for music from the top New York artists recording for a cluster of independent labels, primarily Fania, Coco, Tico, Alegre, and Salsoul.

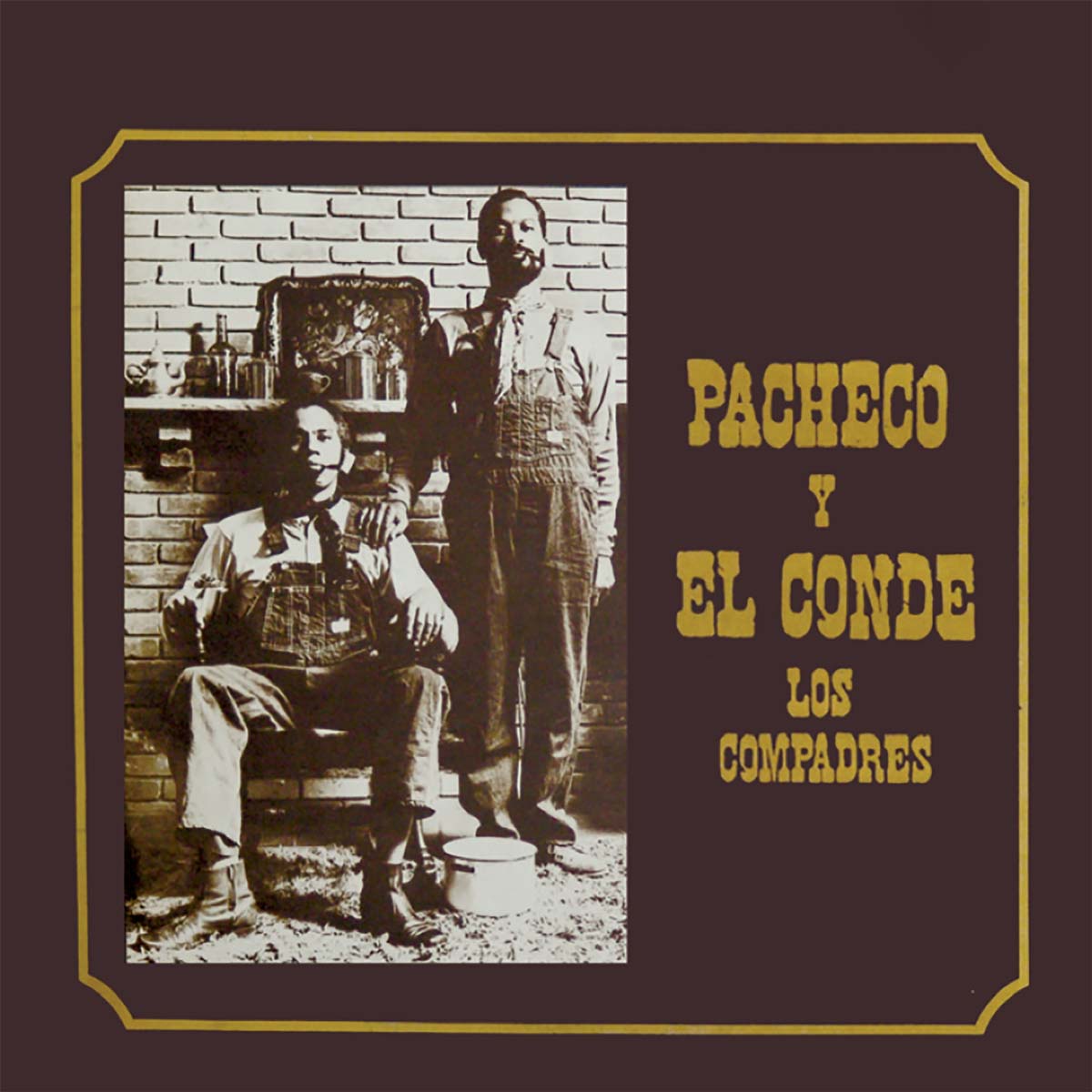

The new music was hard to find in California. Even at Berkeley, which boasted a couple of cutting-edge record stores, the Latin music sections were small and poorly stocked, if you could find them. So, when my girlfriend (and future wife) announced she was making a summer trip to Manhattan, I eagerly asked her to bring me back some salsa albums – any salsa albums. She returned with the Holy Grail of new Afro-Caribbean music – top albums by Willie Colon, Larry Harlow, Ismael Rivera, Santos Colon, and Johnny Pacheco with vocalist Pete “El Conde” Rodriguez. I listened to them alone in my cozy apartment, on the upper floor of a home in Oakland, overlooking the tree-tops, absorbed by the sounds of a different culture.

In those days, salsa albums generally stuck to a loose formula, a mix of dance tracks (mambo, son, cha-cha-cha, guaracha, merengue), along with a couple of boleros, often one per side. Keeping the flame alive 50 years later, the podcast Radio Alimaña recently posted a one-hour compilation of boleros by various artists on Fania Records, including the much-admired Hector Lavoe and the under-appreciated Justo Betancourt.

Eventually, my record collection had exposed me to the canon of Cuban and Puerto Rican boleros, expanding on my parents’ Mexican-influenced song selection featured in Part 1. Below are some of the boleros that I discovered during that ear-opening era. These songs touched me from the start and have stayed with me since then.

“Convergencia” by Johnny Pacheco & Pete “Conde” Rodriguez

I was immediately captivated by the lyrical and melodic mystique of this old bolero, with lyrics by Bienvenido Julián Gutiérrez and music by Marcelino Guerra. It was composed in 1938 and first recorded the following year in New York by Cuarteto Caney, featuring famed Cuban bandleader Machito and Puerto Rican singer Johnny López. I first heard it on a 1972 compilation album, Ten Great Years, by Johnny Pacheco, the Dominican bandleader who co-founded Fania Records, the label that spearheaded the salsa boom of the 1970s. The tune originally appeared on Pacheco’s 1967 album Sabor Típico, featuring the sublime vocals of Afro-Puerto Rican singer Pete “Conde” Rodriguez. As a team through the early 1970s, Pacheco and “El Conde” would produce a series of popular albums featuring a “típico” sound with a conjunto lineup, tighter and more compact than the salsa big bands of the 1950s. Those traditional albums were like primary textbooks in my early salsa education.

This song still holds mystery for me. Clearly, it’s about heartache and lost love that makes you lose sleep (novelesco insomnio do’ vivió el amor), but the conclusion still escapes me. The one-word title (“convergence”) never appears in the song as a noun. The single use of the word is as a verb in the final line, where the singer says he is like “the straight line that converged” (la linea recta que convergió). But converged with what? It’s not clear, at least to me. To make matters worse, there are small inconsistencies in various versions of the lyrics, online and in liner notes, that make big differences. Is it “de playas y olas?” Or “de playas solas?” Is it “porque la tuya final vivió,” or “al final vivió?”

This song still holds mystery for me. Clearly, it’s about heartache and lost love that makes you lose sleep (novelesco insomnio do’ vivió el amor), but the conclusion still escapes me. The one-word title (“convergence”) never appears in the song as a noun. The single use of the word is as a verb in the final line, where the singer says he is like “the straight line that converged” (la linea recta que convergió). But converged with what? It’s not clear, at least to me. To make matters worse, there are small inconsistencies in various versions of the lyrics, online and in liner notes, that make big differences. Is it “de playas y olas?” Or “de playas solas?” Is it “porque la tuya final vivió,” or “al final vivió?”

In the end, precise words and ambiguous phrasing don’t matter. Just let the feeling carry you. In the middle section, the melody cascades down the musical scale in short phrases, creating a gently flowing sensation, as if pulling the listener downstream to an inevitable end. The sad, five-syllable phrases are like steps on the emotional waterfall:

Madero de nave que naufragó,

piedra rodando,

sobre sí misma,

alma doliente

vagando a solas

de playas, olas,

así soy yo:

La línea recta que convergió

porqué la tuya final vivió.

The brilliant arrangement on the Pacheco/Conde recording uses overlapping horns to echo the cascading melody. Sadly, no arranger is credited on the album (Fania LP 339). Ironically, Fania would eventually become known as the label that meticulously credited musicians, composers, and arrangers on its releases, reversing the anonymity that prevailed in the Latin music industry during earlier decades.

The Frontera Collection has a 78-rpm version of that early recording by Cuarteto Caney (Decca 21047B). Identified as a bolero-son, it opens with a solo trumpet playing the entire melody before the singing starts, an unusual approach. A full version is available on YouTube.

This is the only copy of the song in the database, but it has been recorded many times over the decades. In Cuba, fans treasure the 1980s duet by revered sonero Miguelito Cuní with singer-songwriter Pablo Milanés, the New Song icon who also recorded a solo vocal in 1978 with Cuban jazz pianist Emiliano Salvador. Another notable recording, despite the strangely unsynchronized harmonies, is the duet between Cuban singer Omara Portuondo (of Buena Vista fame) and the song’s co-composer, Marcelino Guerra, nicknamed Rapindey. Omara’s fellow Buena Vista vocalist recorded a tender, touching rendition on his 2007 album, Mi Sueño, with the sensitive piano accompaniment of Roberto Fonseca.

Half a century after that Pacheco recording, contemporary musicians keep finding new ways to interpret the bolero. In 2014, a genre-busting, mind-bending version was recorded by none other than the son of El Conde, trumpeter Pete Rodriguez Jr., who holds a doctorate of musical arts from the University of Texas at Austin. The new version released the following year by Destiny Records on the album El Conde Negro, shows that the song has no stylistic boundaries. This is not your father’s bolero anymore.

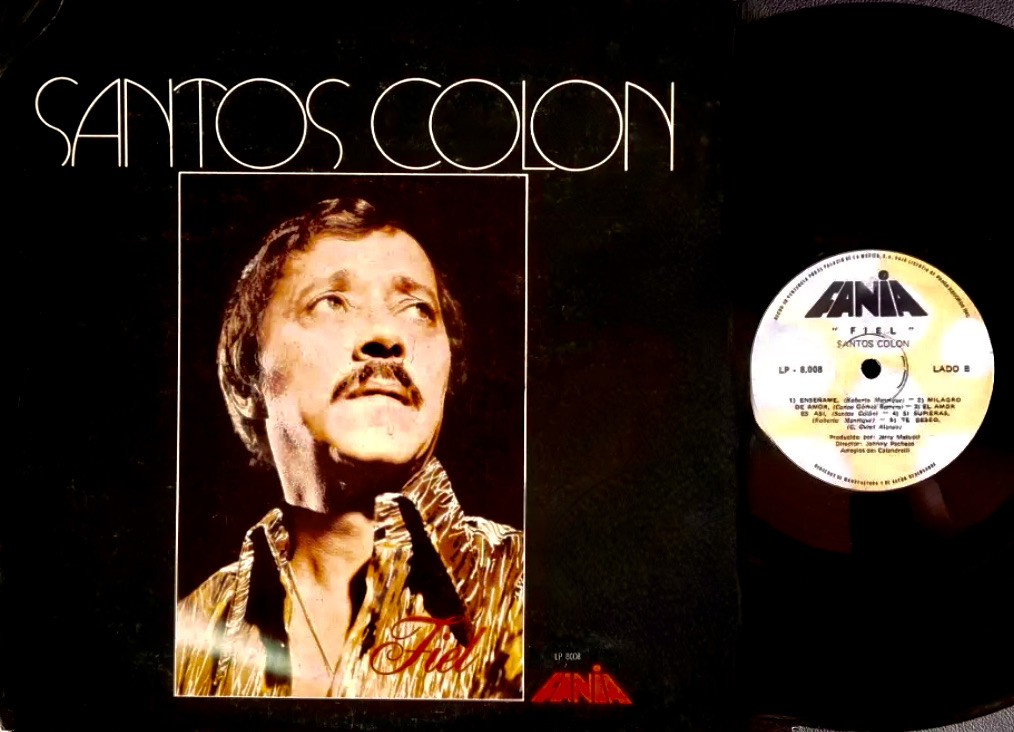

“Usted” by Santos Colon

In its one-word title, this sad song gives a cryptic clue to its meaning, though at the end, it’s still a bit of a mystery.

The title is the formal variant of the pronoun “you” in Spanish. “Usted” is used, rather than the informal “tu,” when addressing a figure of respect: an elder, a parent, a teacher, or simply a stranger. It connotes both distance and unequal status in a relationship. In this case, the use is completely incongruous, since the speaker is supposedly addressing a person of great intimacy, perhaps a former lover who presumably has left, and left behind a broken heart.

“Usted” is included on Colon’s 1972 album, Fiel (Fania Records SLP 430), a 10-track set of love songs tastefully arranged by Argentina’s Jorge Calandrelli. The song was composed by two prominent Mexican songwriters, music by Gabriel Ruiz and words by José Antonio Zorrilla. They blend so well together, the song feels like it blossomed from a single creative mind.

“Usted” is included on Colon’s 1972 album, Fiel (Fania Records SLP 430), a 10-track set of love songs tastefully arranged by Argentina’s Jorge Calandrelli. The song was composed by two prominent Mexican songwriters, music by Gabriel Ruiz and words by José Antonio Zorrilla. They blend so well together, the song feels like it blossomed from a single creative mind.

I found 30 recordings of the song in the Frontera Collection, with two of special interest, both recorded in Mexico. First, the popular trio Los Tres Diamantes bring their high-pitched harmonies and hyper-romantic approach to the song, released by RCA at all three playback speeds – 78, 33, and 45. On another RCA Victor recording, composer and pianist Ruiz accompanies emotive Mexican vocalist Amalia Mendoza, primarily known for her rancheras. In this rendition, prominent arranger and bandleader Chucho Ferrer provides restrained orchestration that spotlights the singer while adding lovely musical embellishments throughout.

I first heard the song in the smooth, honeyed voice of Santos Colon, a Puerto Rican artist who had fronted the high-powered dance band of Tito Puente, and who, at the time of this release, was still performing with the explosive Fania All Stars. As a soloist, affectionately nicknamed Santitos, he was known for his understated but compelling bolero interpretations.

In the case of “Usted,” the typical bolero theme seems obvious at first. It’s about a man who has had his heart broken by a woman who is “the blame of all my anguish and all my losses,” who filled his heart with “sweet restlessness and bitter disappointments.”

Usted es la culpable

De todas mis angustias y todos mis quebrantos

Usted llenó mi vida

De dulces inquietudes y amargos desencantos

It is only at the end that we realize this guy’s been suffering from afar. He uses “usted” because they are, in fact, strangers and he’s been hoping to get up the nerve to kiss her.

Usted me desespera

Me mata, me enloquece

Y hasta la vida diera por vencer el miedo

De besarla a usted

With that revelation from what turns out to be an obsessed but timid admirer (stalker?), the use of the formal “usted” packs a powerful surprise punch, perhaps more disturbing than romantic. But make no mistake, bolero fans read it as a love story, as illustrated by the following comment from a fan on a YouTube clip of the song from Los Panchos.

Cecilia Posadas writes: “I owe my very existence to this song. My grandfather was a whisker away from losing my grandmother, but one night he took her this song in a serenata. They got back together that same day, they married, and they had my dad. ❤” (Le debo mi existencia a esta canción, mi abuelo estaba a nada de perder a mi abuelita pero una noche le llevó serenata con esta canción, regresaron ese día, se casaron y tuvieron a mi papá ❤.)

“Dos Gardenias” by Angel Canales

This is perhaps the weirdest version of the oft-recorded bolero, and I can’t get enough of it. The unusual interpretation is not unexpected from an upstart performer known for his offbeat vocal style as “El Diferente.”

Fans loved Canales for his pirate persona, with his bald head, long necklaces, and gold lamé outfits. His band’s arrangements are jazzy and hip, although his lyrical themes are fairy traditional – paens to Puerto Rico, Nuyorican culture, social musings, and, of course, torch-songs-to-kill-yourself-by (corta-venas), such as “La Hiedra” and “Nostalgia,” a bolero tango.

Canales’s voice is decidedly, and deliberately, non-traditional. His nasal tones and strangely modulated phrasing make him sound like a Latino Bob Dylan. In an aching, desperate song like “Dos Gardenias,” written in 1945 by Cuban pianist and songwriter Isolina Carrillo, the singer’s edgy style adds an additional dose of anguish to the seething jealousy, as if he were losing his mind as well as his heart.

The two gardenias of the title are a symbolic gift from one lover to another, explicitly representing their two hearts. It’s a good choice of imagery, since the white flower is said to represent purity, trust, and hope. However, a sense of suspicion and potential betrayal arises in the final line:

“Pero si un atardecer

Las gardenias de mi amor se mueren

Es porque han adivinado

Que tu amor me ha traicionado

Porque existe otro querer

Where did that poisonous possibility come from? He suddenly refers to the specter of a potential infidelity, to be revealed by the death of the gardenias. It makes you wonder if, despite all the prior romantic lyrics, the flower-giver already suspects he’s losing her love.

If so, that suspicion would align with another trait that gardenias symbolize – clarity. But that’s not necessarily a good thing, explains Florgeous.com, a website devoted to flowers:

“In fact, you could use a gardenia flower to show that you know more than you need to know.”

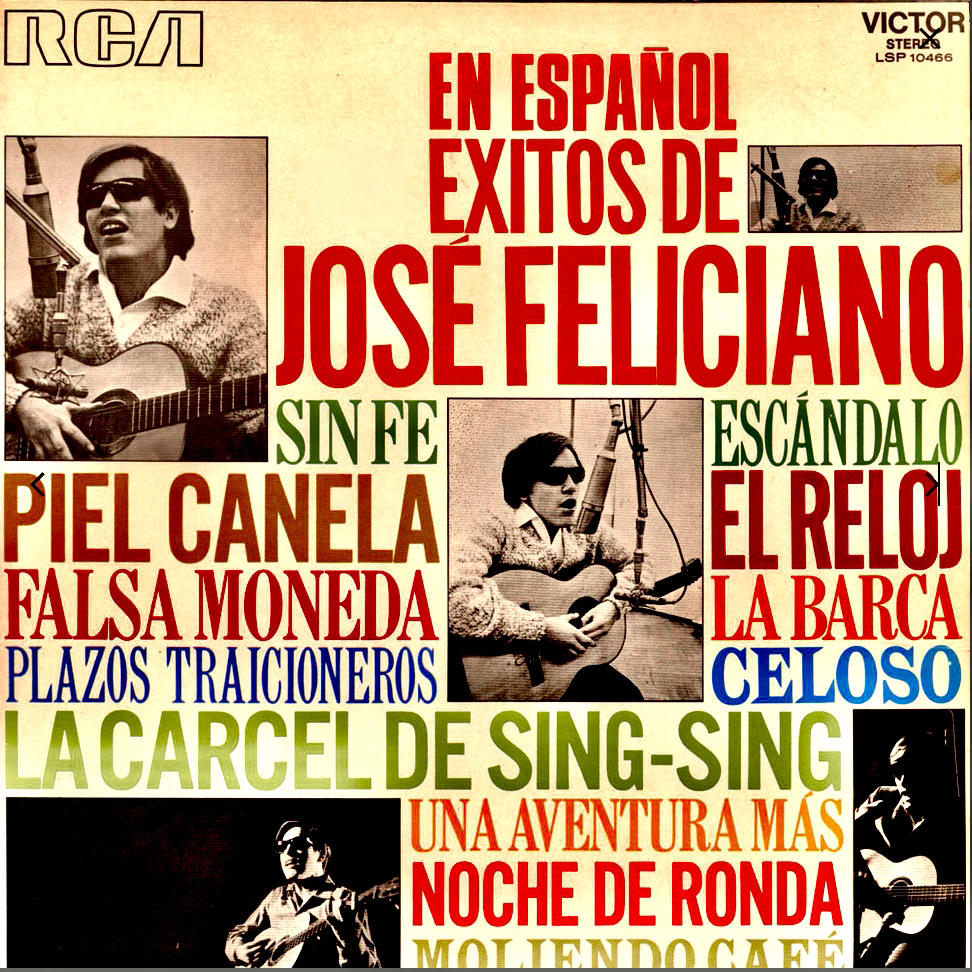

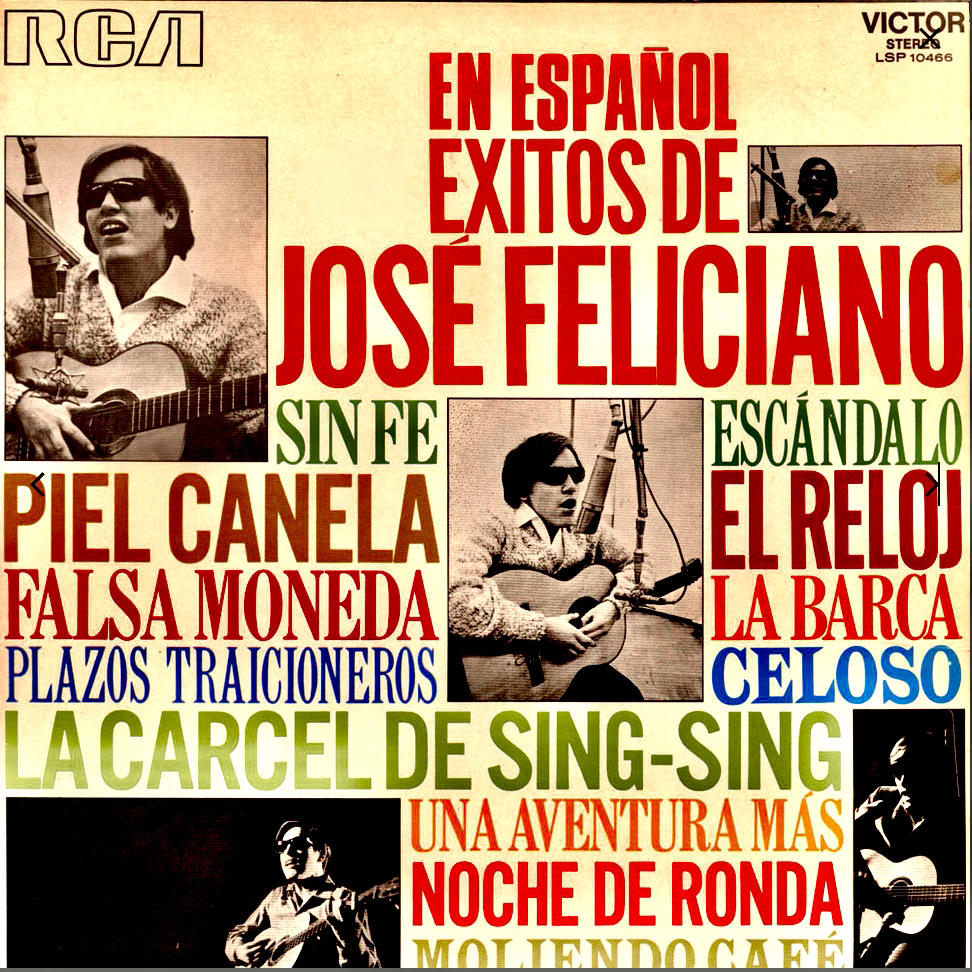

“Sin Fe” by Jose Feliciano

Most people know this Puerto Rican singer and guitarist by his two biggest hits: “Light My Fire” and “Feliz Navidad.” The Doors cover was released in June 1968 on the the singer’s first big hit album for RCA Victor, titled Feliciano!. But by then, Feliciano had recorded a series of Spanish-language albums featuring nothing but boleros: Sombra, Una Guitarra y Boleros (1966, live at Mar de Plata, Argentina), Más Éxitos de José Feliciano (1967), and El Sentimiento, La Voz y la Guitarra de José Feliciano (1968).

Most people know this Puerto Rican singer and guitarist by his two biggest hits: “Light My Fire” and “Feliz Navidad.” The Doors cover was released in June 1968 on the the singer’s first big hit album for RCA Victor, titled Feliciano!. But by then, Feliciano had recorded a series of Spanish-language albums featuring nothing but boleros: Sombra, Una Guitarra y Boleros (1966, live at Mar de Plata, Argentina), Más Éxitos de José Feliciano (1967), and El Sentimiento, La Voz y la Guitarra de José Feliciano (1968).

As a die-hard Doors fan, I cringed at Feliciano’s lightweight “Light My Fire.” But I loved his bolero albums, which predated Luis Miguel’s “Romance” series by 20 years. For some weird reason, these are the only LPs I brought with me on a Christmas trip to Juarez in 1973, the whole family packed in a rented mobile home to share the holidays with the south-of-the-border Gurzas. I was playing the records on my Tía Laura’s console when an incredulous cousin asked, “Is he really that popular over there?”

By that time, yes, he was. Not for these bolero recordings but for the song that was to become a ubiquitous Christmas standard, “Feliz Navidad,” released November 24, 1970, on the album of the same name. Both hit albums – the Christmas collection and the album of rock covers – were helmed by Rick Jarrard, an RCA staff producer who also worked with Jefferson Airplane, Harry Nilsson, and others.

While Feliciano’s mainstream pop career took off, I was still stuck on his bolero collections. His Mas Exitos contains a bushel of classics, including “Noche de Ronda,” “Piel Canela,” and “El Reloj.” It also contains my featured song, “Sin Fe,” written by Puerto Rican singer-songwriter Bobby Capó, who also wrote “Piel Canela.”

“Sin Fe” is sometimes called “Poquita Fe,” a variant used for all 24 of the recordings in the Frontera Collection. That includes the first recording of the song credited to Jorge Valente, a bolero ranchero released in 1960 by Discos Columbia on a 45-rpm extended play (Columbia EPC-244-A-1), with the backing of Mariachi Mexico de Pepe Villa. The track comes from Valente’s debut LP on Colombia, Love in Mexico, although the prominent mariachi bands are not credited on the U.S. release (Columbia EX 5132). Other notable versions in the database include the recording by Trio Los Panchos with three-part harmonies, and an instrumental rendition by Flaco Jimenez on accordion and Ry Cooder on slide guitar. (The 13 recordings titled “Sin Fe” in our database are entirely different songs.)

By any title, I feel entranced by this song’s aching melody, with almost hopeless tones reflecting the title, “Without Faith.” It’s really one broken heart singing to another, across the gap of pain, disappointment, and betrayal. The singer acknowledges his own destructive failings in the relationship, doesn’t blame his disillusioned partner for doubting him, and finally pleads for her help in restoring his ability to love, and to forgive. His approach is low-key and soft-spoken. But at the end, there’s a musical flourish that embellishes the singer’s emotional appeal for restored trust and love.

Feliciano’s natural, earthy vocals help convey the flesh-and-blood yearning and despair of the bolero style, which is deeper and more mature than the common pop love song. The feelings are enhanced on these albums by the traditional arrangements, mostly guitars and light percussion. In 1998, perhaps in an attempt to ride the coattails of Luis Miguel’s bolero success, Feliciano put out a new album called Señor Bolero, with a bigger orchestral sound that smothered the songs.

That album didn’t touch me like his early work did. You can feel the difference, and the feeling is missing.

“Lo Mismo Que Usted” by Fania All Stars

Tito Rodriguez is another Puerto Rican crooner known for his cool style and velvety voice. He was big in the 1950s during the mambo craze in New York, part of a troika of bandleaders who dominated the dance floor at New York’s Palladium ballroom, along with Tito Puente and Machito. During that era, I was a kid buying singles at my local record store by Elvis Presley, Fabian, and The Four Seasons. Twenty years later, I discovered a whole new blend of salsa music through a popular album by the Fania All Stars titled Tribute to Tito Rodriguez. It was released by Fania Records in 1976, when I was starting to carve out a career in music journalism, freelancing for the Los Angeles Times and Billboard Magazine. In October of that year, I wrote a review for the Times of the local debut of the Fania All Stars at the Hollywood Palladium.

The All Stars had been conceived as a showcase for the label, representing the roster’s premiere singers and bandleaders in one supergroup. From the start in 1968, the ensemble conveyed the excitement and spontaneity of the music through live recordings of shows staged especially for that purpose. That led to a series of live albums that propelled the scrappy startup to stardom – Live at the Red Garter (1968), Live at The Cheetah (1972), Latin-Soul-Rock (1974), and Live at Yankee Stadium (1975).

The tribute to Tito Rodriguez was their first studio LP, featuring songs popularized by the Nuyorican singer who, like Santos Colon, jumped from the big-band dance format to the softer stylings of the bolero, which perfectly suited his romantic style. The album opens with an intricately constructed, ten-minute medley of three boleros sung by three different singers – “Inolvidable” by Cheo Feliciano, “Lo Mismo Que a Usted” by Chivirico Davila, and “Tiemblas” by Bobby Cruz. Composed of three separate tunes written by three different composers with charts by three different arrangers, the medley manages to sound like a single composition in three movements. It’s a theatrical, romantic opening for an album that goes on to feature up-tempo dance numbers.

“Lo Mismo Que a Usted” was written in 1965 by a pair of Argentinean songwriters, Palito Ortega and Dino Ramos, each famous in his own right. Ortega, a popular pop singer, made the first recording of his composition on April 12, 1965, more as a ballad than a bolero. Though not as widely known as other standards of the genre, it has been recorded by a host of artists, a sampling of which you can hear on this Amazon Music playlist.

The Frontera Collection contains six versions, including a live recording by Tito Rodriguez during what was to be his final concert in 1972 at El Tumi, a nightclub in Lima, Peru. The beloved singer would die of leukemia early the following year, at the young age of 50. The live album of his final show, backed by La Sonora de Lucho Macedo, was released posthumously in 1973 by his own label, TR Records, titled 25th Anniversary Performance, a milestone that had marked the occasion for the show in Peru.

Frontera also contains recordings of the song by Nuyorican bandleader Ray Barretto, Argentine vocalist Roberto Yanes, and Mexican tropical band La Sonora Santanera.

Once again, the song lyrics use the formal, respectful “usted” in addressing the other party in the dialog. Once again, the grammatical usage raises questions about the relationship between the two. The lyrics are expository, laying out details of the singer’s lonely and heart-broken condition. The litany of woes is interspersed with the line, “lo mismo que usted” (the same as you), repeated seven times. So, we have a lonely-hearts club of two people, maybe strangers, mired in misery, and perhaps reaching for some connection in their shared isolation.

A mí me pasa lo mismo que a usted.

Me siento solo, lo mismo que usted.

Paso la noche llorando,

La noche esperando, lo mismo que usted.

A mí me pasa lo mismo que a usted.

Nadie me espera, lo mismo que usted.

Porque se sigue negando el amor

Que voy buscando, lo mismo que usted.

Cuando llego a mi casa y abro la puerta,

Me espera el silencio.

Silencio de besos, silencio de todo,

Me siento tan solo, lo mismo que usted.

To this day, Tito Rodriguez is the song’s best interpreter. His mellow, mournful vocals suit the song’s interior gloom and sad resignation.

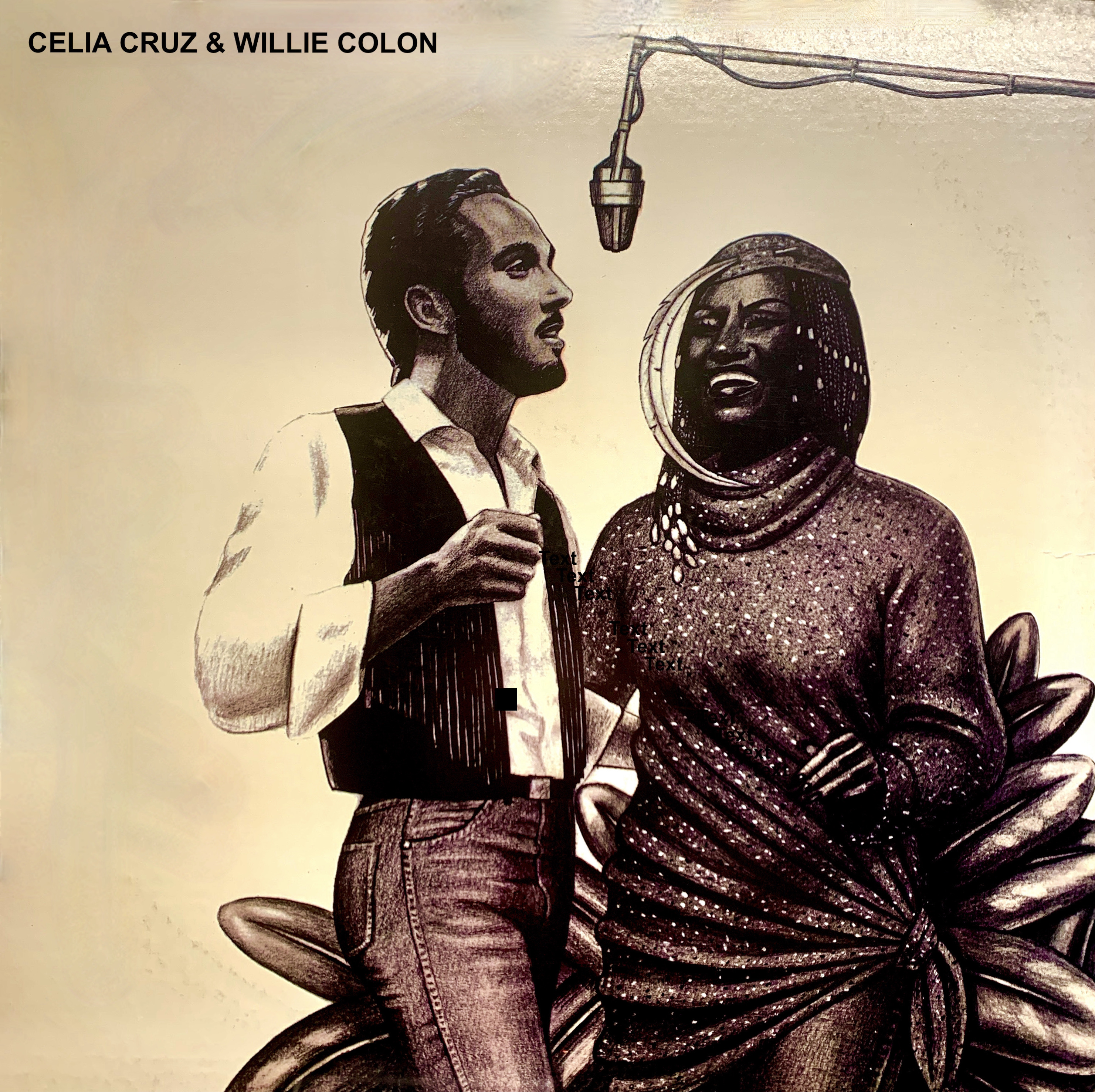

“Plazos Traicioneros” by Celia Cruz & Willie Colon

In English, this song could be called “Why Do You String Me Along?” That’s the nut of the theme, longing for love dangled just beyond reach, always tempting, never fulfilled. “Plazos Traicioneros” was written in 1953 by Cuban songwriter, Luis Marquetti (1901-1991), who was also a teacher, poet, and unpublished novelist. Nicknamed El Gigante del Bolero, Marquetti wrote more than five dozen songs, including “Deuda,” the one that launched his career in 1945.

In English, this song could be called “Why Do You String Me Along?” That’s the nut of the theme, longing for love dangled just beyond reach, always tempting, never fulfilled. “Plazos Traicioneros” was written in 1953 by Cuban songwriter, Luis Marquetti (1901-1991), who was also a teacher, poet, and unpublished novelist. Nicknamed El Gigante del Bolero, Marquetti wrote more than five dozen songs, including “Deuda,” the one that launched his career in 1945.

I first heard the song on one of those bolero albums by Jose Feliciano, and the haunting melody became one of my favorites. My featured version above is by salsa stars Celia Cruz and Willie Colon from their first studio collaboration, Only They Could Have Made This Album. The song title is tricky to translate. Some lyric websites have it as “Treasonous Times,” but that smacks of political intrigue. In Spanish, “plazos” can mean deadline, or simply a specified time period, or a pause. And “traicioneros” can mean treasonous, as well as duplicitous and disloyal. So, a more accurate translation, without the lyricism, could be “periods of betrayal.”

In three verses and a bridge, the singer questions the motives behind the constant foot-dragging by the target of his affections. Every time he declares his love to her, she responds, “Let’s see if tomorrow might be the day you get what you want.” In the lovely bridge section, before the final verse, he reveals the insecurity that is filling him with desperation. He asks if she is putting him off because “another has stolen your heart from me.”

Cada vez que te digo lo que siento,

tu siempre me respondes de este modo,

“Deja ver, deja ver,

si mañana puede ser lo que tu quieres.”

Pero asi van pasando las semanas,

pasando sin lograr lo que yo quiero.

Yo no se, para que,

para que son esos plazos traicioneros.

Traicioneros porque me condenan

y me llenan de desesperación.

Yo no se si me dices que mañana

porque otro me robó tu corazón.

Cada vez que te digo lo que siento,

no sabes como yo me desespero.

Si tu Dios es mi Dios,

para que son esos plazos traicioneros.

The song shines in this version produced by Willie Colon and arranged by veteran producer, arranger, and bandleader Louie Ramirez. The Spanish-style guitar of Yomo Toro adds beautiful accents, while the band provides a subtle, understated backup. Celia’s rich, modulated lead vocal is complemented by brief, perfectly placed harmonies, presumably between her and Colon, who also does lead vocals on his own solo albums.

Their rendition is one more gem in one of Celia’s biggest selling albums. It also includes the Brazilian-based hit, “Usted Abusó,” which roughly means “you took advantage of me.” With its sturdy resolve in the face of rejection, the song is a counterpoint to “Plazos Traicioneros,” because in this case, the suitor is not willing to wait around and take more abuse.

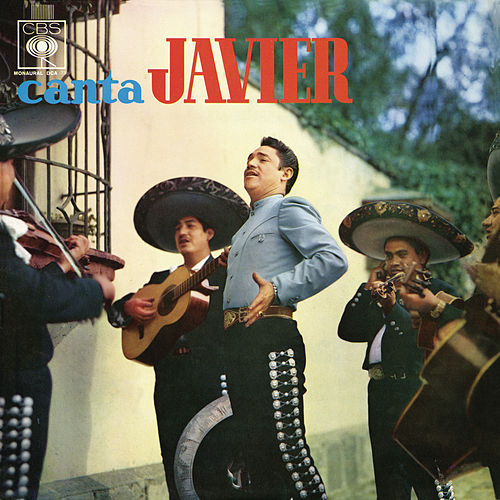

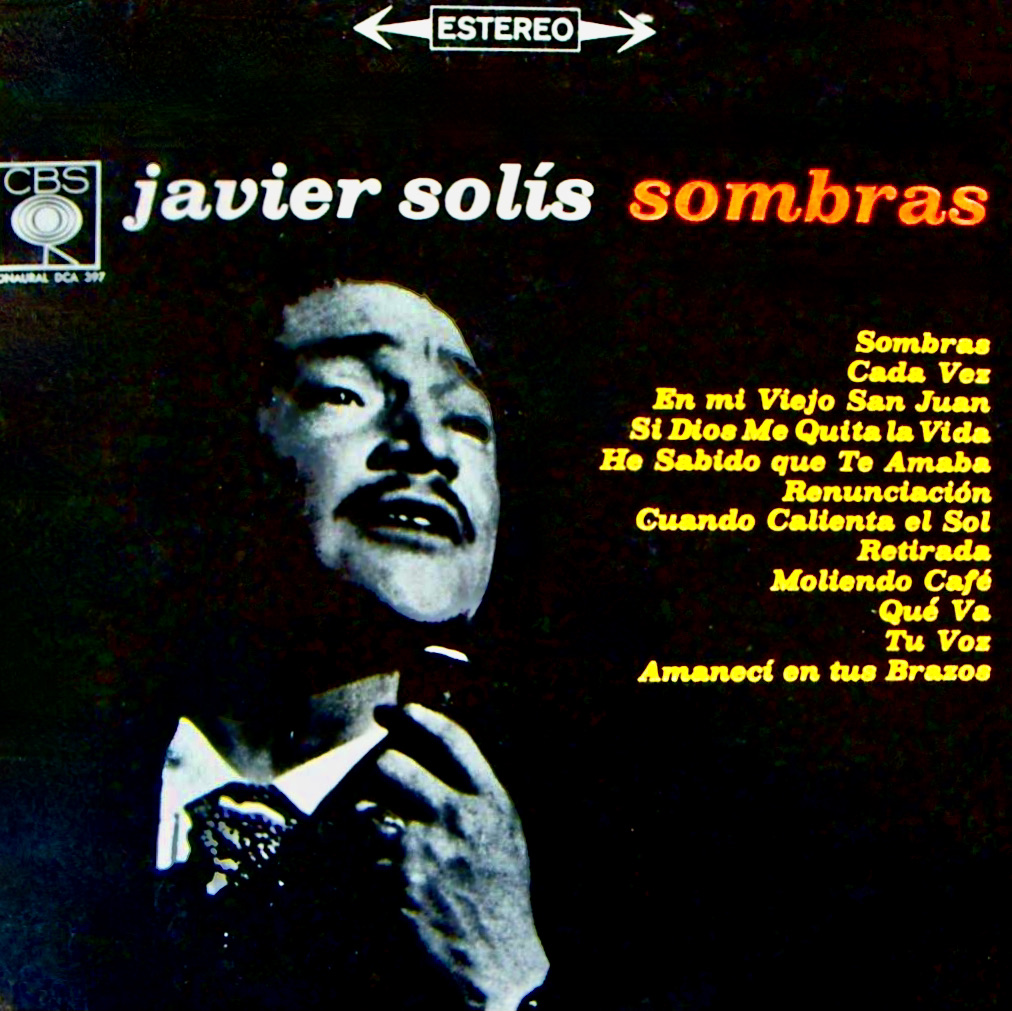

“Sombras” and “Amanecí en Tus Brazos” by Javier Solis

I can’t write about my college years without mentioning these two songs. They are the stalwart bookends, the opening and closing tracks, on an album by Mexico’s cosmopolitan crooner Javier Solis, released in 1966 by CBS in Mexico as “Sombras” and in the U.S. as “Romance in the Night.” The following year, after graduating from high school, I moved to Mexico City to attend the National University, and these songs were in the air, everywhere. They were hits that transcended class, race, and neighborhood boundaries. It seemed like the whole country was transfixed by the voice of Javier Solis.

I can’t write about my college years without mentioning these two songs. They are the stalwart bookends, the opening and closing tracks, on an album by Mexico’s cosmopolitan crooner Javier Solis, released in 1966 by CBS in Mexico as “Sombras” and in the U.S. as “Romance in the Night.” The following year, after graduating from high school, I moved to Mexico City to attend the National University, and these songs were in the air, everywhere. They were hits that transcended class, race, and neighborhood boundaries. It seemed like the whole country was transfixed by the voice of Javier Solis.

For me, this music triggers a warm nostalgia that transports me to that specific time and place, as music often does. As a teenager raised from infancy in the United States, I remember the songs as part of the soundtrack of my induction into Mexican society, part of my own cultural immersion program. And just like this life-changing experience left an indelible mark on my mind, these tunes will always echo in my head.

Thematically, the two songs could not be more different.

“Sombras” was originally written as a tango in 1943 by Francisco Lomuto and José María Contursi. It was adapted for mariachi for Solis, known as El Rey del Bolero Ranchero. In either format, the song is a dark, desperate cry from a man on the verge of killing himself over lost love that left him in the “shadows” of his life. In the shocking opening lines, he says he wants to slice his veins and let his blood flow at her feet, proving his boundless love with his death. Talk about corta-venas!

“Amanecí en Tus Brazos,” on the other hand, is brimming with the joy of true love. Written by Mexico’s prolific composer, José Alfredo Jimenez, the song expresses how lovers can get lost in each other, lose track of time, revel in intimacy from morning to night, with the moon and the dawn as their only witnesses. The opening line sets the mood: “Amanecí otra vez entre tus brazos / Y desperté llorando de alegría” (I arose once again within your arms, and I awoke weeping of joy).

These songs express the polar extremes of relationships, from blissful love to suicidal loss. And within that range of romantic experience, lives the bolero.

– Agustín Gurza

Also in this series:

The Eternal Bolero, Part 1: Love Songs That Endure for Decades

Blog Category

Tags

Images