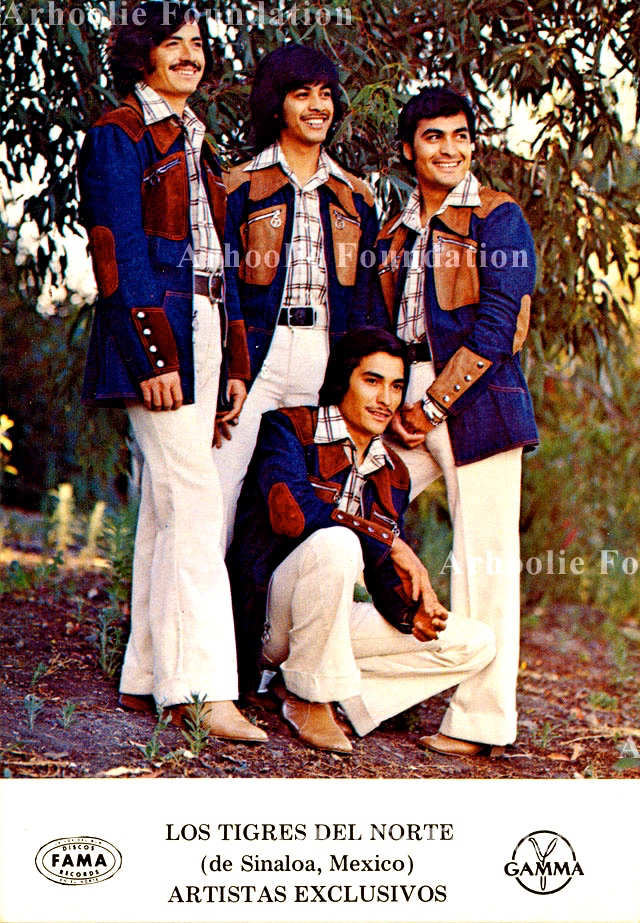

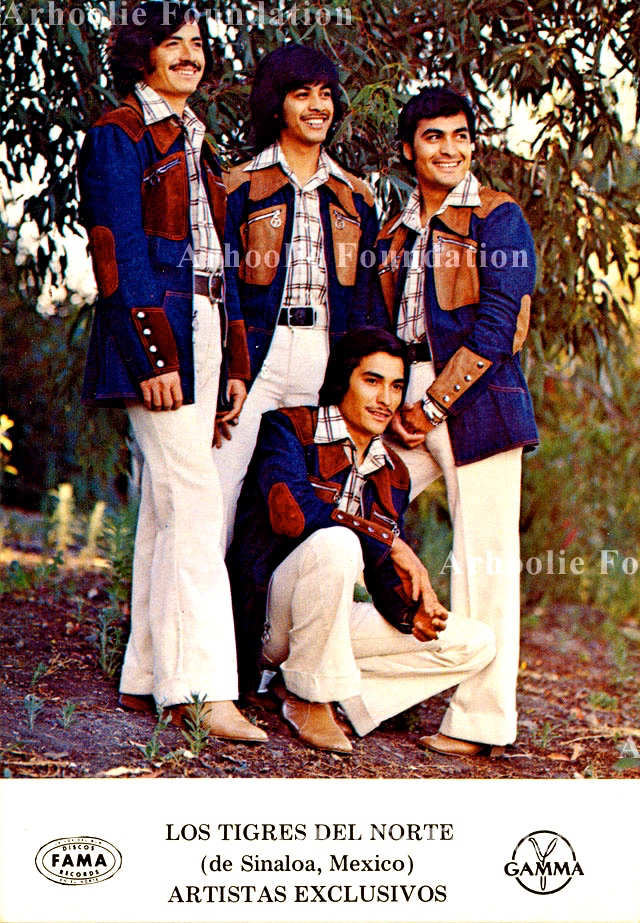

The four brothers who make up Los Tigres del Norte, the world’s premier Mexican norteño band, have been playing corridos since they were boys growing up in Mexico. In keeping with the music’s oral tradition, they learned their first songs from older musicians in their hometown, a tiny rural hamlet with the poetic name Rosa Morada, the Purple Rose, in Sinaloa state. The Hernández boys had no sheet music, no songbooks, no albums or tapes to guide their instruction in this rustic folk genre. In fact, they didn’t even have access to a radio in their rancho. It was the 1960s, and the brothers – Hernán, Luis, Jorge and Eduardo – were starting to perform informally as a local group. They could not have dreamed that they would eventually become known throughout the world as one of the most enduring, beloved, and critically respected bands in the Mexican norteño genre. Their story is one of struggle, family devotion, charmed choices and an unwavering commitment to a musical vision.

The four brothers who make up Los Tigres del Norte, the world’s premier Mexican norteño band, have been playing corridos since they were boys growing up in Mexico. In keeping with the music’s oral tradition, they learned their first songs from older musicians in their hometown, a tiny rural hamlet with the poetic name Rosa Morada, the Purple Rose, in Sinaloa state. The Hernández boys had no sheet music, no songbooks, no albums or tapes to guide their instruction in this rustic folk genre. In fact, they didn’t even have access to a radio in their rancho. It was the 1960s, and the brothers – Hernán, Luis, Jorge and Eduardo – were starting to perform informally as a local group. They could not have dreamed that they would eventually become known throughout the world as one of the most enduring, beloved, and critically respected bands in the Mexican norteño genre. Their story is one of struggle, family devotion, charmed choices and an unwavering commitment to a musical vision.

Los Tigres’ hometown is no more than a cluster of homes surrounded by farmlands, near the city of Mocorito in northwestern Mexico. Its fame today is due entirely to its most successful native sons, who left over 40 years ago. Their parents were campesinos, small farmers who worked the land with ox-drawn ploughs. Jorge, the eldest son, born in 1954, still recalls one of the biggest events in the life of his little town—the day his grandmother brought home a Philco radio. It was the only electronic contraption of its kind in town, and nobody was sure it would even work, considering the area’s hilly terrain. Amid the static, it managed to pull in just one radio signal – a 150,000-watt powerhouse from Harlingen, Texas, which played pure norteño music, “música de acordeón.” That’s when the eldest brother heard the music of major norteño artists for the first time, groups like Freddie Gómez, Los Donneños, and Los Dos Gilbertos, who were already making waves across the border, who were known only in the United States at the time.

During fiestas in the brothers’ hometown, people set up an old Victrola with a bullhorn for a speaker hung from a post and turned it up full blast. At those parties they were introduced to other big-name norteño acts such as Los Alegres de Terán, as well as national mariachi stars such as Pedro Infante. Aside from commercial music, they picked up on oral traditions from the older men of their town who taught the boys old corridos about bandits and rebels, horses and heroes. They memorized verse after verse about historic and folkloric figures such as Gabino Barrera, Lucio Vasquez, Rosita Alvirez, and Pancho Villa. “They knew them all, start to finish, and they knew them by heart,” recalls Jorge . “We would just sing them that way and we didn’t know if we were right or wrong, because we had no record or documentation to say this is the original. Later, when I came to read the lyrics of these corridos, they coincided with the lyrics they had taught us.”

Jorge always thought of being a professional singer. He aspired to communicate through his music, “to convey to people our history, our way of life, how we act and who we are.” He yearned to let the world know that what they played was more than just cheap beer-joint music—“música de cantina”—that people with good taste looked down on. “When we started to sing this kind of music, everybody said we were crazy. The more they stubbornly stuck to the negative idea that what we believed in wasn’t possible, the more I was determined to show just the opposite, with deeds.”

When the elder Hernández was not yet twelve, a tragic accident ironically became the catalyst for the launch of their musical career. In 1966, his father suffered a serious back injury that left him unable to walk. To raise money for his medical care, Jorge and his brothers decided to take their act on the road. As a band, they still didn’t have a name. They were known around town simply as the Hernández boys – “los hijos de Lalo y Consuelo” – called to play at parties. With the family in a bind, they decided to go out and look for regular work every night, in addition to their day jobs. “So we made a kind of pact among brothers to support our father,” says Jorge.

Soon, they were in demand as far away as Los Mochis, the coastal city where the elder brother had gone to study to be a teacher. They played a regular gig at a restaurant, singing at tables for tips. But still they were the band with no name. “People sort of called us whatever they wanted,” says Hernández. “Los Norteñitos de Chihuahua. Los Alegres de Rosa Morada. Wherever they wanted us to be from, that’s what they called us.”

Pressed to earn even more money for their father’s medical bills, they decided to move to the border town of Mexicali, where they hit the city’s busy bar and restaurant circuit. Here, to their amazement, they could draw a dollar a song. They got so busy they even took on a manager and acquired a van so they could work venues all across town from noon to dawn. It was here in Mexicali that they caught the break that would change their lives, and the future of norteño music forever.

In order to send money home, Jorge made regular visits to the telegraph office in Mexicali. By chance, the telegraph worker who handled his business also happened to book acts for state-sponsored fairs all across Baja, California. One day the man told Hernández of an opportunity for his band to perform in the United States. A promoter in San Jose, California, had put the word out that state authorities were looking for Spanish-language acts to entertain Mexican inmates at the prison in Soledad. The gig did not pay, but it would give the boys exposure. And with a 90-day visa, they could stay and look for additional gigs in the area. The Hernández brothers jumped at the chance. They were hired as part of a caravan of artists brought in for the prison show.

In order to send money home, Jorge made regular visits to the telegraph office in Mexicali. By chance, the telegraph worker who handled his business also happened to book acts for state-sponsored fairs all across Baja, California. One day the man told Hernández of an opportunity for his band to perform in the United States. A promoter in San Jose, California, had put the word out that state authorities were looking for Spanish-language acts to entertain Mexican inmates at the prison in Soledad. The gig did not pay, but it would give the boys exposure. And with a 90-day visa, they could stay and look for additional gigs in the area. The Hernández brothers jumped at the chance. They were hired as part of a caravan of artists brought in for the prison show.

While filling out their visa papers, a U.S. immigration agent asked what the group called itself, but the boys still didn’t have a name. “Put down whatever you want,” Hernández told him. So the border bureaucrat came up with a name on the spot. In America, he said, boys who exhibit a go-get-’em spunk are often affectionately nicknamed “little tigers.” And since they were headed north, the agent dubbed them the Little Tigers of the North. But on second thought, he eliminated the diminutive so they wouldn’t outgrow the name—should the band remain together, that is.

“He was the one who christened us,” says Hernández. “So when we arrived at Soledad and had to introduce ourselves, I said, ‘Tell them that we are Los Tigres del Norte.’ ”

After the prison performance, the promoter brought the group to San Jose, which has been their base ever since. The city had a growing Mexican-American community at the time, and it planned to celebrate its very first official Mexican Independence Day the following month, on September 16, 1967. The band was hired for the event and the plan seemed to be working fine. But soon, says Hernández, they discovered that the other artists from their prison caravan had vanished, presumably back to Mexico. Also missing: Los Tigres’ passports. But being stranded turned out to be another lucky break: The band started working every Sunday at a spot on the Eastside of town called Paseo de las Flores. It was a popular open-air venue that people nicknamed “El Hoyo,” the Hole, because it was sunken between railroad tracks and the creek. For a time, the band lived in the promoter’s home behind his Mexican store, La Internacional, on Alum Rock Avenue. They made the rounds of bars and restaurants, still passing the hat. They also did live radio shows on KOFY (referred to as Radio “Coffee”), the only Mexican station at the time.

At one of their early shows, a photographer named Richard Diaz approached the band with word about a British-born record distributor who wanted to meet them. His name was Art Walker, and he would become the first person to put the music of Los Tigres on record. At first, remembers Hernández, they couldn’t even communicate, because Walker didn’t speak Spanish and the Tigres hadn’t yet learned English. Fortunately, Walker’s wife was bilingual and served as an interpreter, thus laying the groundwork for what turned out to be one of the most successful relationships in the history of the Mexican music business. Walker (later nicknamed “Arturo Caminante” ) took the group to Fresno that fall to make their inaugural recording, a single titled “De un Rancho a Otro.”

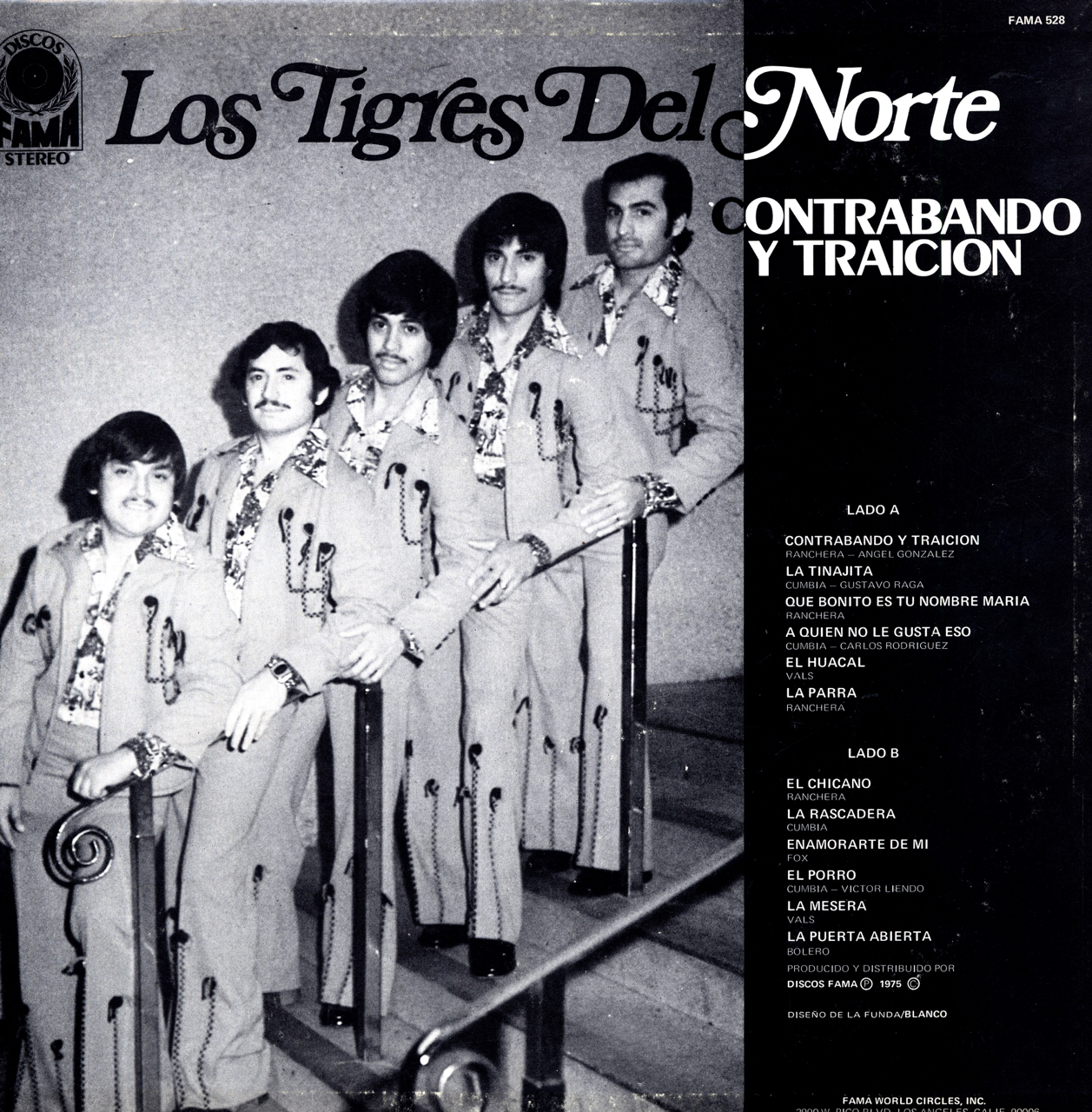

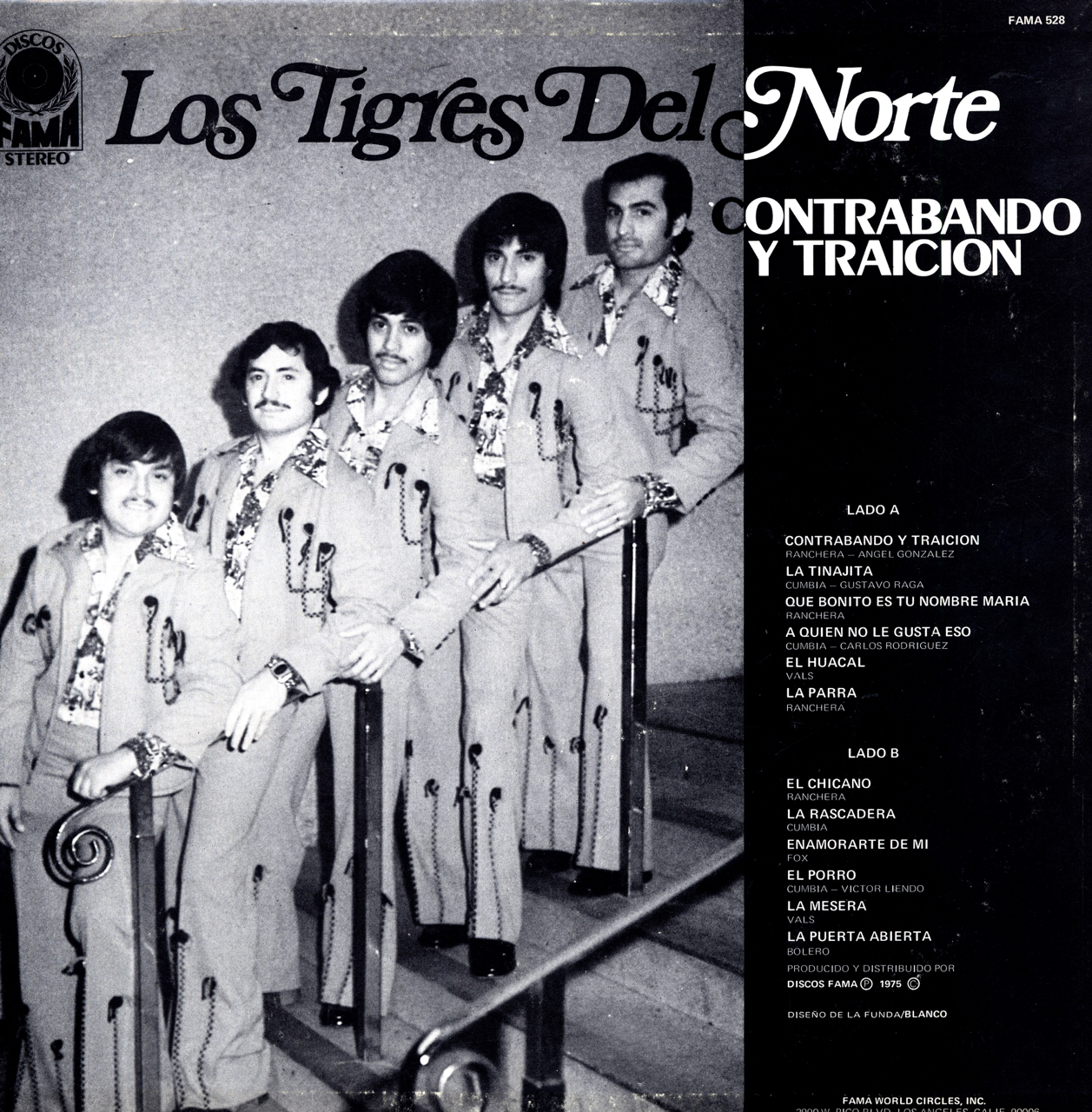

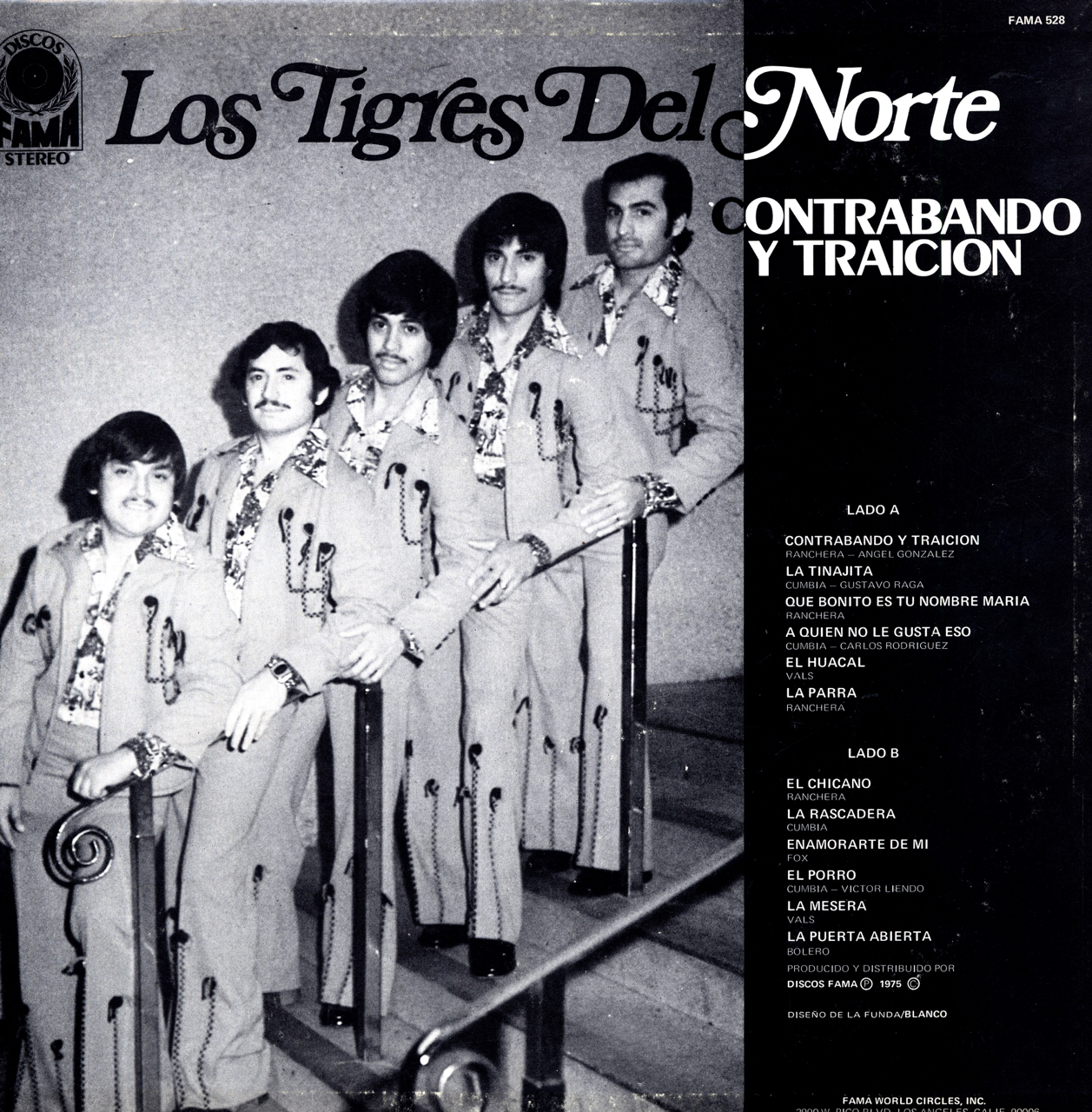

The band was far from an overnight success. It took three years before they had their first big hit, “Contrabando y Traición,” about a drug-smuggling couple whose exploits end in betrayal and murder. Indeed, the song that launched their career helped create the controversial subgenre known today as narcocorridos. That was followed in 1973 by “La Banda del Carro Rojo,” another narcocorrido about a drug-smuggling gang in a red car. Soon, Hernández would realize his goal of bringing his music to an international audience. The big breakthrough came when Los Tigres began to star in Mexican films alongside top performers of the day, such as David Reynoso and Lucha Villa.

The band was far from an overnight success. It took three years before they had their first big hit, “Contrabando y Traición,” about a drug-smuggling couple whose exploits end in betrayal and murder. Indeed, the song that launched their career helped create the controversial subgenre known today as narcocorridos. That was followed in 1973 by “La Banda del Carro Rojo,” another narcocorrido about a drug-smuggling gang in a red car. Soon, Hernández would realize his goal of bringing his music to an international audience. The big breakthrough came when Los Tigres began to star in Mexican films alongside top performers of the day, such as David Reynoso and Lucha Villa.

“And that’s the moment when it all changed for us,” says Hernández. “When people saw us on the screen along with these accomplished and revered artists, they started looking at us with different eyes. The whole panorama changed.”

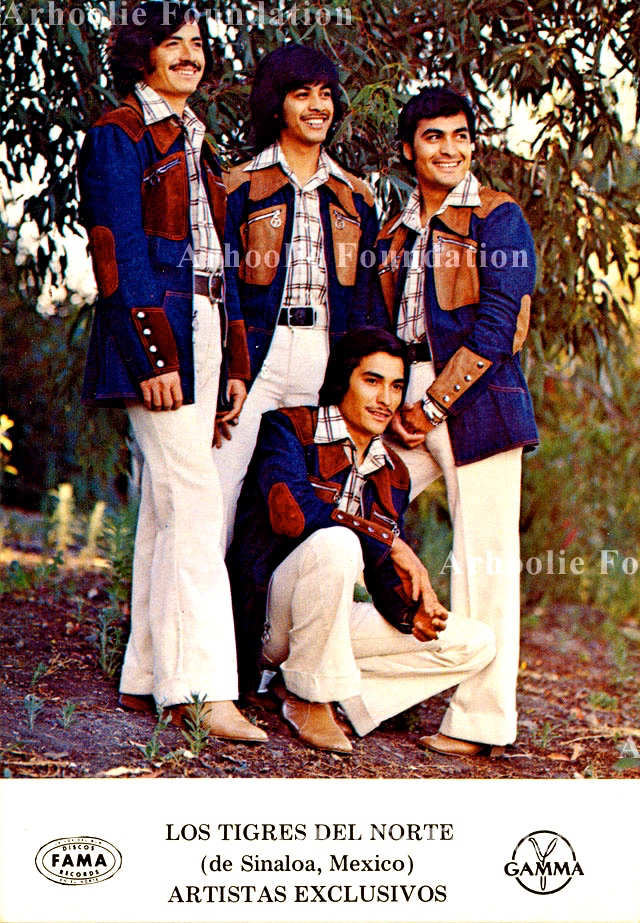

In all, Los Tigres recorded eight albums over 16 years for Walker’s company, Fama Records, helping make it one of the most important Mexican labels on the West Coast in the 1970s. Yet, unbelievably, Hernández says the band was never paid a penny for those records. They made their money from the live concerts, but the label never paid royalties. “Out of gratitude to Arturo, there were never any payments or any of that,” recalls Hernández. “Instead, I recorded with him because we were friends … and Arturo always behaved like a gentleman with me.”

1970s. Yet, unbelievably, Hernández says the band was never paid a penny for those records. They made their money from the live concerts, but the label never paid royalties. “Out of gratitude to Arturo, there were never any payments or any of that,” recalls Hernández. “Instead, I recorded with him because we were friends … and Arturo always behaved like a gentleman with me.”

Eventually, disagreements led the band to seek release from its contract, which in turn led to a lawsuit. Yet again, the band’s problems would become their good fortune. The judge ruled in the band’s favor, says Hernández, giving the group all rights to their songs as well as ownership of their recorded masters, rights which normally stayed with record companies even after artists left their rosters. That old catalog became something of a musical 401K for the group, which retains the rights to this day.

Los Tigres went on to record for Fonovisa, part of the Televisa empire, and broadened its popularity internationally. They have toured Latin America, Europe, and Asia, making them the first global norteño band in history. By the time the band celebrated its 40th anniversary in 2008, they had recorded more than 500 songs on 60 albums, starred in over a dozen films, scored multiple Grammys and sold over 35 million units worldwide. (The Frontera Collection currently contains 145 recordings by Los Tigres, including many of those early Fama tracks.) In 2003 the group performed at the prestigious Kennedy Center in Washington, DC, and four years later won the Latin Recording Academy’s Lifetime Achievement Award. In 2011 Los Tigres broke another barrier by becoming the first regional Mexican act to be featured in the popular recorded concert series MTV Unplugged. Last year, Los Tigres became the first norteño band to get a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

Los Tigres went on to record for Fonovisa, part of the Televisa empire, and broadened its popularity internationally. They have toured Latin America, Europe, and Asia, making them the first global norteño band in history. By the time the band celebrated its 40th anniversary in 2008, they had recorded more than 500 songs on 60 albums, starred in over a dozen films, scored multiple Grammys and sold over 35 million units worldwide. (The Frontera Collection currently contains 145 recordings by Los Tigres, including many of those early Fama tracks.) In 2003 the group performed at the prestigious Kennedy Center in Washington, DC, and four years later won the Latin Recording Academy’s Lifetime Achievement Award. In 2011 Los Tigres broke another barrier by becoming the first regional Mexican act to be featured in the popular recorded concert series MTV Unplugged. Last year, Los Tigres became the first norteño band to get a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

From the very start, Los Tigres have always considered themselves storytellers, like travelling troubadours of old whose songs simply recounted the daily lives and struggles of common people. The corridos they sang were in the best tradition of the genre as journalism put to music, chronicling the exploits of villains and heroes who predated the Mexican Revolution.

“For more than 30 years they have lifted up a music once looked down on for its lower-class roots, making norteño a commercially viable pop music,” wrote music critic Chuy Varela in a 2005 feature story for the San Francisco Chronicle. “Yet there is a higher sense of purpose to what they do. Los Tigres give strength to people who feel marginalized and under attack in these days of widespread anti-immigrant sentiment.”

Perhaps the band’s most enduring cultural accomplishment has been its support for the Strachwitz Frontera Collection at UCLA, starting with a $500,000 donation made in 2000 for the digital preservation and promotion of the music. It was the band’s own thirst for knowledge that led to the massive UCLA project. They had been looking for an authoritative source to provide the musical history that the genre had always been missing. “We read books, but every author had his own version of the story, and they were all different,” says Hernández. “We wanted to know more and we wanted the real history of the corrido.”

Perhaps the band’s most enduring cultural accomplishment has been its support for the Strachwitz Frontera Collection at UCLA, starting with a $500,000 donation made in 2000 for the digital preservation and promotion of the music. It was the band’s own thirst for knowledge that led to the massive UCLA project. They had been looking for an authoritative source to provide the musical history that the genre had always been missing. “We read books, but every author had his own version of the story, and they were all different,” says Hernández. “We wanted to know more and we wanted the real history of the corrido.”

The group’s grant to the university was the first of its kind from a community-based source, helping establish the largest library archive of Mexican and Mexican-American music in the world. Hernández hopes that future generations will also use the Frontera Collection to learn about their cultural history and traditions.

The archives provide in an instant what Los Tigres took a lifetime to discover. “Ours is a group which, like the music itself, came here and has had to work hard to be recognized and acknowledged,” says Hernández. “We didn’t have the technology that exists today. We had to go from rancho to rancho, village to village, city to city, country to country. In other words, we did it all by hand.”

--Agustín Gurza

El Ciego Melquíades, also known as “The Blind Fiddler,” represents a bygone era in Tex-Mex music when small orquestas típicas and rural string bands were still popular. Though little is known about the life of Melquíades Rodríguez, his recording career spanned the 1930s and ’40s and even continued into the postwar era when the fiddle had already given way to the accordion as the centerpiece of Mexican American popular music. He recorded both vocal and instrumental numbers, some at mobile studios set up by labels at hotels in the San Antonio area. At the peak of his career, he was much in-demand at dances, bullfights, and other festive occasions in the area around San Antonio.

El Ciego Melquíades, also known as “The Blind Fiddler,” represents a bygone era in Tex-Mex music when small orquestas típicas and rural string bands were still popular. Though little is known about the life of Melquíades Rodríguez, his recording career spanned the 1930s and ’40s and even continued into the postwar era when the fiddle had already given way to the accordion as the centerpiece of Mexican American popular music. He recorded both vocal and instrumental numbers, some at mobile studios set up by labels at hotels in the San Antonio area. At the peak of his career, he was much in-demand at dances, bullfights, and other festive occasions in the area around San Antonio.

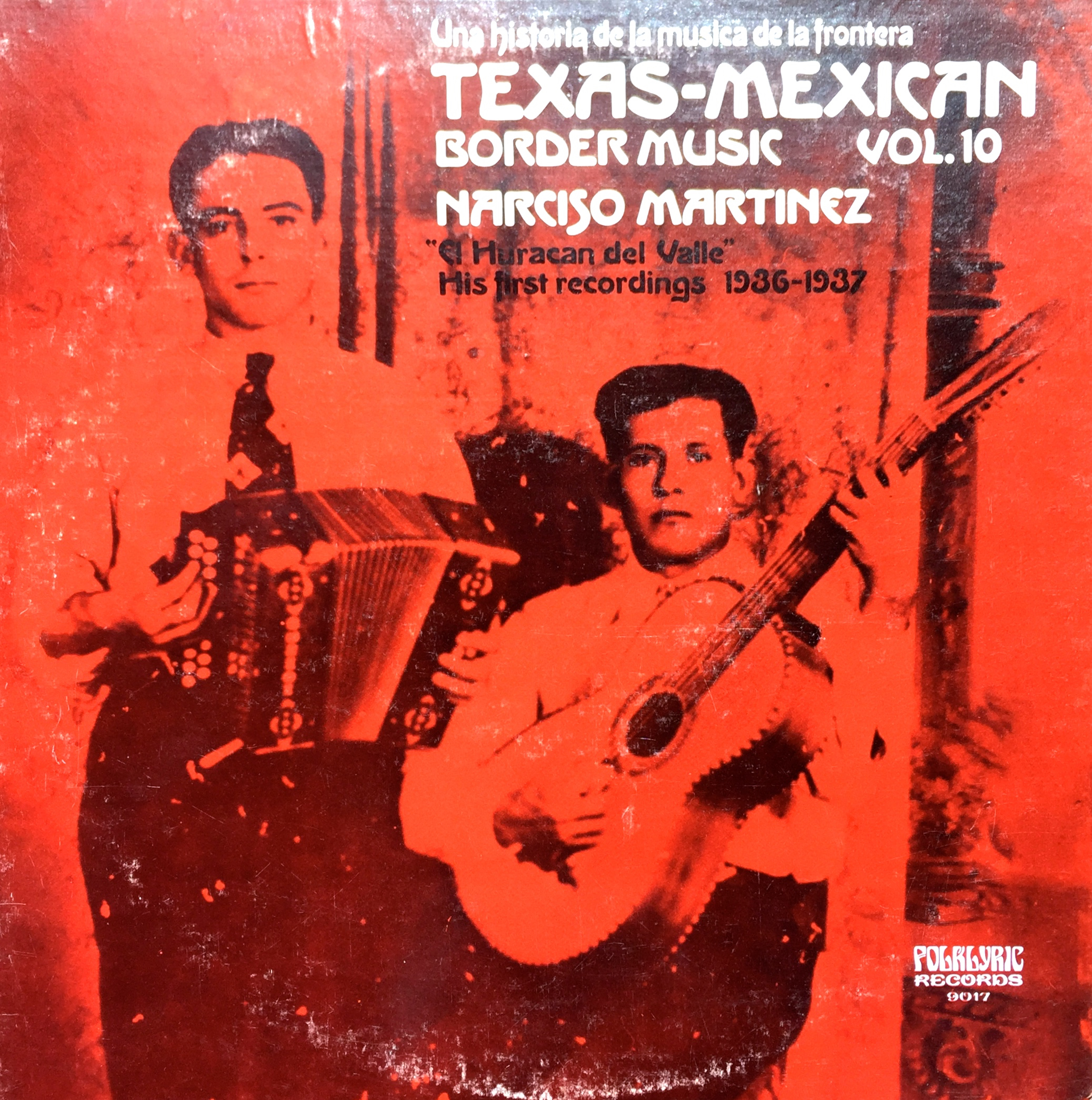

Conjunto music, the accordion style so popular with Mexican Americans throughout the Southwest, comprises a cornerstone of the Frontera Collection. Yet conjunto as such does not appear on the list of Top 20 genres compiled for my

Conjunto music, the accordion style so popular with Mexican Americans throughout the Southwest, comprises a cornerstone of the Frontera Collection. Yet conjunto as such does not appear on the list of Top 20 genres compiled for my