Lola: Honoring Eva Garza’s Legacy

It’s not often that so-called millennials lead us back to music from the past century, especially Latin music. Showbiz today is all about being young, fresh, and new.

It’s not often that so-called millennials lead us back to music from the past century, especially Latin music. Showbiz today is all about being young, fresh, and new. Blog Category

Tags

Images

It’s not often that so-called millennials lead us back to music from the past century, especially Latin music. Showbiz today is all about being young, fresh, and new.

It’s not often that so-called millennials lead us back to music from the past century, especially Latin music. Showbiz today is all about being young, fresh, and new.

Singer Eva Garza launched her singing career as a teenager in San Antonio, Texas, and emerged as one of the few Mexican-American artists to gain international acclaim throughout the Americas. An accomplished and seductive interpreter of the romantic bolero, she collaborated during the 1940s and ’50s with top figures in the field, including Mexico’s Agustin Lara and Cuba’s Isolina Carrillo.

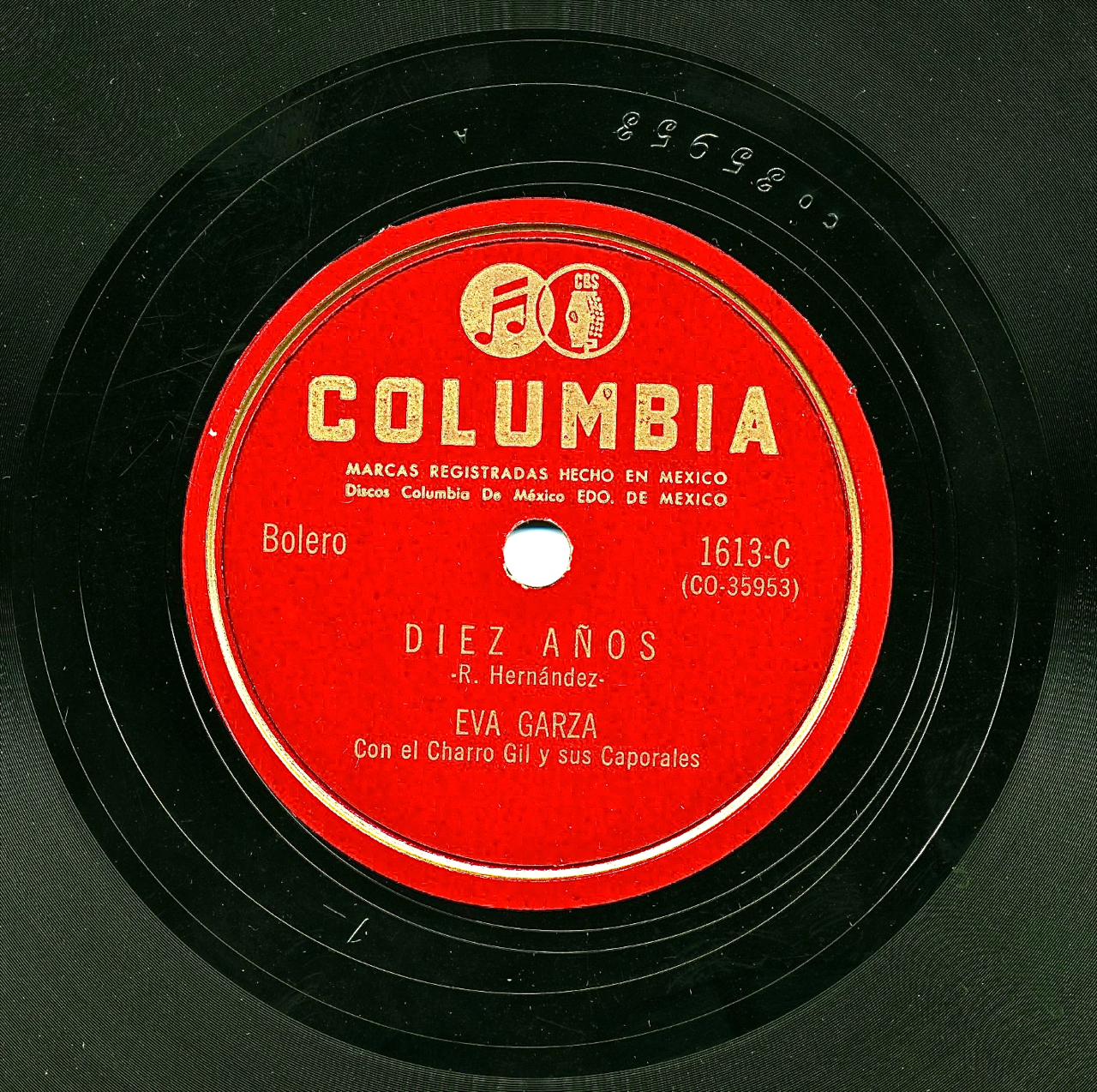

Singer Eva Garza launched her singing career as a teenager in San Antonio, Texas, and emerged as one of the few Mexican-American artists to gain international acclaim throughout the Americas. An accomplished and seductive interpreter of the romantic bolero, she collaborated during the 1940s and ’50s with top figures in the field, including Mexico’s Agustin Lara and Cuba’s Isolina Carrillo. Garza recorded for several major labels, including Columbia Records, which issued her earliest recordings in New York where she had relocated to pursue her career. Though she died less than a year before reaching her 50th birthday, she left a deep and rich recorded catalog. Garza ranks No. 32 on the list of the top 50 most-recorded performers in the Frontera Collection, with 154 recordings in the archive. Singer Chelo Silva, a fellow Texan also known for boleros, ranks higher in the archive at No. 6, possibly because Silva hailed from the border town of Brownsville and kept a more regional profile on Tex-Mex labels, a Frontera specialty.

Garza recorded for several major labels, including Columbia Records, which issued her earliest recordings in New York where she had relocated to pursue her career. Though she died less than a year before reaching her 50th birthday, she left a deep and rich recorded catalog. Garza ranks No. 32 on the list of the top 50 most-recorded performers in the Frontera Collection, with 154 recordings in the archive. Singer Chelo Silva, a fellow Texan also known for boleros, ranks higher in the archive at No. 6, possibly because Silva hailed from the border town of Brownsville and kept a more regional profile on Tex-Mex labels, a Frontera specialty. As a student at Lanier High School, Garza also excelled at sports. Her accomplishments as an all-star athlete in basketball and baseball were documented in the local press during the 1930s. The dynamic newspaper photos of Garza in her athletic uniforms – spotlighting a star athlete who was also female and Mexican-American – inspired her peers in an era when segregation and sexism were rampant.

As a student at Lanier High School, Garza also excelled at sports. Her accomplishments as an all-star athlete in basketball and baseball were documented in the local press during the 1930s. The dynamic newspaper photos of Garza in her athletic uniforms – spotlighting a star athlete who was also female and Mexican-American – inspired her peers in an era when segregation and sexism were rampant. Garza then hit the road, with a touring schedule that would take her throughout Mexico, Central and South America, as well as Cuba and the Caribbean. It was during one of those tour stops in Juarez, Mexico, that Garza met the man who would become her first husband. On December 30, 1939, she married Felipe “El Charro” Gil, whose Trio Los Caporales was a precursor of the wildly popular Trio Los Panchos that featured his brother, Alfredo Gil. After a hometown Texas wedding, the couple settled in New York City. Garza performed as a soloist with different ensembles, but she also performed with her husband, as on this recording of “Diez Años,” an aching bolero by Rafael Hernandez, backed by “Eso Si…Eso No…,” a spirited tune written by Gil and backed by his Caporales.

Garza then hit the road, with a touring schedule that would take her throughout Mexico, Central and South America, as well as Cuba and the Caribbean. It was during one of those tour stops in Juarez, Mexico, that Garza met the man who would become her first husband. On December 30, 1939, she married Felipe “El Charro” Gil, whose Trio Los Caporales was a precursor of the wildly popular Trio Los Panchos that featured his brother, Alfredo Gil. After a hometown Texas wedding, the couple settled in New York City. Garza performed as a soloist with different ensembles, but she also performed with her husband, as on this recording of “Diez Años,” an aching bolero by Rafael Hernandez, backed by “Eso Si…Eso No…,” a spirited tune written by Gil and backed by his Caporales. From the beginning, there were strains in the relationship that would ultimately dissolve the marriage. “Much to Gil’s dissatisfaction, Garza would keep her last name,” writes Vargas in her book. “Neither Gil nor many of the promoters Garza came across thought it was appropriate that she travel solo as a married woman and so eventually Gil would reduce his time as musician and devote most of his efforts to managing her career.”

From the beginning, there were strains in the relationship that would ultimately dissolve the marriage. “Much to Gil’s dissatisfaction, Garza would keep her last name,” writes Vargas in her book. “Neither Gil nor many of the promoters Garza came across thought it was appropriate that she travel solo as a married woman and so eventually Gil would reduce his time as musician and devote most of his efforts to managing her career.” Garza moved to Mexico City in 1949, establishing herself there as one of the biggest singing stars during the early 1950s. She became a regular on the capital’s influential radio station XEW, sharing star-studded lineups with the biggest names of the day, such as Pedro Infante, Pedro Vargas, Javier Solis, and Jorge Negrete. And in the studio, she recorded songs by the top composer’s of a golden era in Mexican pop music, songwriters such as Agustín Lara, Gonzalo Curiel, and Joaquín Pardavé. Overall, Garza recorded more than 200 tracks for major labels, including Decca, RCA, Columbia and Musart. Among her other big hits from this period are “Sin Motivo,” “Frio en el Alma,” and “La Última Noche.”

Garza moved to Mexico City in 1949, establishing herself there as one of the biggest singing stars during the early 1950s. She became a regular on the capital’s influential radio station XEW, sharing star-studded lineups with the biggest names of the day, such as Pedro Infante, Pedro Vargas, Javier Solis, and Jorge Negrete. And in the studio, she recorded songs by the top composer’s of a golden era in Mexican pop music, songwriters such as Agustín Lara, Gonzalo Curiel, and Joaquín Pardavé. Overall, Garza recorded more than 200 tracks for major labels, including Decca, RCA, Columbia and Musart. Among her other big hits from this period are “Sin Motivo,” “Frio en el Alma,” and “La Última Noche.” Garza’s real life ended sadly and prematurely, but not nearly as tragically. In 1953, she divorced “El Charro” Gil, with whom she had had three children, including a son, Felipe Gil, a successful singer and songwriter in his own right, also known by the stage name Fabricio. (Felipe Gil, the younger, made news in 2014 when, at age 73, he announced he was transgender and taking the name Felicia Garza, adopting his mother’s surname.) The couple also had two daughters who were in show business. The late Rosa María Bojalil Garza had a brief singing career in Mexico, recording a 1963 album of pop/rock covers for RCA Victor under the stage name Corinna. Her sister, Laura, was a backup singer, model, and actress, and is now a Florida businesswoman. In 1965, Eva Garza remarried, this time to Argentine artist Abel Reynosa, with whom she moved to Buenos Aires.

Garza’s real life ended sadly and prematurely, but not nearly as tragically. In 1953, she divorced “El Charro” Gil, with whom she had had three children, including a son, Felipe Gil, a successful singer and songwriter in his own right, also known by the stage name Fabricio. (Felipe Gil, the younger, made news in 2014 when, at age 73, he announced he was transgender and taking the name Felicia Garza, adopting his mother’s surname.) The couple also had two daughters who were in show business. The late Rosa María Bojalil Garza had a brief singing career in Mexico, recording a 1963 album of pop/rock covers for RCA Victor under the stage name Corinna. Her sister, Laura, was a backup singer, model, and actress, and is now a Florida businesswoman. In 1965, Eva Garza remarried, this time to Argentine artist Abel Reynosa, with whom she moved to Buenos Aires.

El Ciego Melquíades, also known as “The Blind Fiddler,” represents a bygone era in Tex-Mex music when small orquestas típicas and rural string bands were still popular. Though little is known about the life of Melquíades Rodríguez, his recording career spanned the 1930s and ’40s and even continued into the postwar era when the fiddle had already given way to the accordion as the centerpiece of Mexican American popular music. He recorded both vocal and instrumental numbers, some at mobile studios set up by labels at hotels in the San Antonio area. At the peak of his career, he was much in-demand at dances, bullfights, and other festive occasions in the area around San Antonio.

El Ciego Melquíades, also known as “The Blind Fiddler,” represents a bygone era in Tex-Mex music when small orquestas típicas and rural string bands were still popular. Though little is known about the life of Melquíades Rodríguez, his recording career spanned the 1930s and ’40s and even continued into the postwar era when the fiddle had already given way to the accordion as the centerpiece of Mexican American popular music. He recorded both vocal and instrumental numbers, some at mobile studios set up by labels at hotels in the San Antonio area. At the peak of his career, he was much in-demand at dances, bullfights, and other festive occasions in the area around San Antonio.

Melquíades Rodríguez began his recording career in the early 1930s when he made several records as a singer and guitarist with various partners. By this time, however, the era of the string bands and small orquestas típicas, which flourished at the turn of the century and into the 1920s, was fading rapidly from the pop music scene among Mexican Americans in south Texas. The instrumental ensembles were replaced by vocal duets with guitars, which became the popular sound on records, radio, and jukeboxes. At the same time, the accordion was replacing the violin at dances – especially in the country where full orchestras were an extravagance few could afford. Despite these changes in musical tastes, Rodríguez’s talents caught the attention of a recording director who made room for tracks that spotlighted the musician’s fiddle work. During the latter part of a recording session in 1935, Rodríguez laid down four tracks, two polkas and two waltzes, with his fiddle front and center. A pattern of recording some vocal selections along with several fiddle tunes then persisted through early 1937. By September of that year, the label officially billed Rodríguez by his handicap as El Ciego Melquíades, or The Blind Fiddler. Apparently the fiddle solos were successful enough to warrant El Ciego to be asked back into the studio several more times before the record company ceased its regional recording activities in San Antonio in late 1938.

During World War II, most recordings of regional and vernacular music ceased due to a shortage of shellac. By the late 1940s, however, a host of small local labels sprang up all over the country trying to fill the demand from jukebox operators. By then, the music which Rodríguez played on the fiddle, once so common on both sides of the border, was a fading tradition, rapidly replaced by the much louder and sturdier accordion. Still, El Ciego Melquíades stands out among his Depression-era peers as the most popular and enduring exponent of that bygone violin tradition.

“I think he played in a more fluent and rural style while the others were perhaps better trained musicians,” writes producer Chris Strachwitz in the liner notes to San Antonio House Party (Arhoolie 7045), a compilation of El Ciego’s recordings. “He was also apparently a very well-liked man who appeared at many house parties, restaurants, bars, and on the streets of San Antonio.”

Years after his music faded, fans from San Antonio continued to remember El Ciego’s legendary performances at house parties where he would play all night long. Conjunto star Fred Zimmerle of Trio San Antonio recalled that his brother Henry used to play guitar with El Ciego during the 1940s. Though they knew little about his background or private life, fans had fond memories of the man and his music.

Mexican writer Hermann Bellinghausen identifies disparate musical strains that influenced El Ciego’s lively playing style – from the fiddlework native to the huasteca region of southern Mexico, to the square dance sounds of Tennessee and Texas, and even the more refined violin tradition of Mexico’s Juventino Rosas, a 19th century composer and violinist. Rodríguez’s style is showcased on some four dozen 78-rpm recordings included in the Frontera Collection. Selections on the aforementioned Arhoolie compilation, released in 2002, come mostly from the artist‘s heyday in the 1930s. The 20-track disc features polkas, waltzes, fox-trots and mazurkas, with El Ciego’s violin backed by guitar, violoncello, and string bass accompaniment. The last two selections are taken from 78s on the Corpus Christi-based AERO label from the late 1940s, which are apparently the last sides El Ciego made on fiddle. He did record once more for IDEAL but again as a singer and guitarist.

“It’s sentimental, good-time Texas Mexican-American music with some bright humor,” wrote pop music critic Richie Unterberger in an online review of the Arhoolie compilation

El Ciego’s work has also been documented in a book of original transcriptions and arrangements of 34 songs from his repertoire, written by Vykki Mende Gray, artistic director of Los californios, a project of the non-profit organization San Diego Friends of Old-Time Music. “These transcriptions finally make this music accessible and available,” states the project website, urging music lovers “to discover … the delights of this piece of Mexican and tejano heritage.”

--Agustín Gurza

The Story of Hymie Wolf and Rio Records

During World War II, national record companies such as Victor, Columbia, and Decca just about stopped recording and releasing regional music in the United States. In those years, the major labels were battling a strike by the musicians union and facing a shortage of shellac, the material used to press records. After the war was over, local entrepreneurs sensed a great, pent-up public demand for recordings by local performers, especially from tavern owners who had jukeboxes. With no experience in the music industry, many of these local businessmen started their own record labels from scratch, buying essential record-making equipment: a disc cutter, blank acetates, a mixer, and a couple of microphones. Manuel Rangel Sr., who ran an electrical repair business that serviced jukeboxes in the San Antonio area, was by most accounts the pioneer of Tejano record labels starting with the release of a tune by accordion player Valero Longoria on Rangel’s Corona label, probably in early 1948.

Not far behind, however, was another small business owner from San Antonio named Hymie Wolf, who founded Rio Records in what used to be his liquor store. He remodeled the liquor store into a record shop and set up the recording studio in a back room. The letterhead of this one-man operation proudly announced ”Wolf Recording Company, Home of the Rio Record.”

Located at 700 West Commerce Street in the heart of San Antonio’s bustling downtown area, the store was just a few blocks east of the Plaza del Zacate where produce was the main business. Here all kinds of folks would congregate, and in the evenings they would listen to strolling musicians or buy hot tamales from street vendors. Just a few blocks to the south, off South Santa Rosa Street, was a busy area of honky-tonks and cantinas where Tejanos and Mexicanos would socialize, imbibe, dance, carouse, or relax at the end of a day of hard labor or try to drink away their problems. They would listen to live conjuntos or to recordings on a jukebox, which was often better, and of course cheaper, at repeating favorite songs endlessly to one’s heart’s desire.

By the late 1940s, musical ensembles known as conjuntos (groups) typically featuring two harmonizing voices, an accordion, a bajo sexto, and a string bass, were making the music that Spanish-speaking factory hands, truck drivers, and other blue-collar workers wanted to hear. Strolling musicians of all sorts, including duets with guitars, trios, mariachis, as well as conjuntos, wandered from cantina to cantina in search of customers willing to pay for songs to be delivered on the spot. Singers had to know the latest hits and sing them well in order to compete with the jukeboxes. For dancing, however, musicians were hired for the evening. There, in addition to an appealing vocal delivery, stamina, and endurance, musicians needed instrumental prowess, rhythmic energy, and cohesion to be popular with the dancers. Many of the musicians also began to learn that if they could come up with their own songs, they could earn extra money by getting their compositions into the hands of established recording stars.

Some of the singers and musicians who found their way into Wolf’s backroom recording studio were already established artists who had been making a living with their music for some time. There was San Antonio’s premier corridista, Pedro Rocha, who had recorded extensively in the 1930s and was well known on the local music scene. Also recording for Rio were Juan Gaytan and Frank Cantú (aka Pancho Cantú), popular San Antonio singers and composers who had been on the music scene for many years. Lydia Mendoza’s sisters, Juanita and María working as the duo Las Hermanas Mendoza, were also a big name in San Antonio having started their career at the Bohemia Club there during the war.

However, most of the performers to appear on the Rio label were young upstarts determined to be heard. The first artists to appear on a Rio 78rpm disc were the dueto of Andres Alvarez and Polo Cruz. The two were accompanied by accordionist Jesus Casiano, who was already an established recording artist from the pre-war era. The label read “Alvarez y Cruz y Los Tejanos” and the first song, Rio No. 101, was “Mujer de las Cantinas” (Woman of the Bars)! Honky-tonk music had arrived and Rio Records, during the brief decade of its existence, documented some of the finest Spanish-language examples of this genre in San Antonio. Indeed, these Rio recordings constitute an authentic audio snapshots of a vibrant culture and tradition which came to life and threw off its old conservative shackles during the social and economic boom period of the post-World War II era.

Fred Zimmerle, along with his brothers, started his career on Rio and became one of the best and most beloved accordionists with his Trio San Antonio. Valerio Longoria came over to Rio and introduced the high-tone bolero to cantina patrons. Tony de la Rosa, on his way to becoming the polka king of South Texas, cut some early sides for Rio (as Conjunto De La Rosa) while visiting San Antonio. Conjunto Alamo, with Leandro Guerrero or Felix Borrayo on accordion and Frank Corrales on guitar, became very popular around San Antonio. Pedro Ibarra also became a well-respected musician in town and remained active on the local music scene all the way through the 1990s. And Los Pavos Reales came to San Antonio from nearby Seguin to become major stars of conjunto music.

A young man named Leonardo Jimenez, strongly influenced by Pedro Ibarra, made his first records for Rio with Los Caminantes . One of Don Santiago Jimenez’s sons, he became world-famous 20 years later as Flaco Jimenez. (The Frontera Collection contains 73 tracks by Los Caminantes on Rio. Those first recordings by Flaco Jimenez and Henry Zimmerle with Los Caminantes are available on a compilation CD, Arhoolie 370, titled Flaco’s First.)

Many of the artists on Rio Records were young rebels, in some waysthe equivalent of today’s blues, rap, or punk musicians: Los Tres Diamantes, Los Chavalitos, Conjunto Topo Chico, Conjunto San Antonio Alegre, and from the lower Rio Grande Valley, Armando Almendarez, the accordionist who had obviously listened to the jukebox records of the King of Louisiana Zydeco, Clifton Chenier. An authentic Tejano orchestra, Alonzo y Sus Rancheros, as well as the classy ranchera singer Ada García , who had a marvelously soulful voice, also appeared on the label.

Perhaps some of these singers and musicians would have found their way to other enterprising upstart record producers, as many of them later did, but few producers seemed to have had the kind of rapport, enthusiasm, and congenial relationship with the artists as Hymie Wolf . Besides all the fun and joviality evident on these recordings, the enthusiastic music merchant turned Rio Records into a successful, if limited and short-lived, enterprise with the help of his personality, resources, business experience, and the all-important cooperation of local singers and musicians.

Wolf was the last of four sons born in San Antonio to Morris and Rose Wolf, who themselves were both born in Russia. His father had a clothing store on Commerce Street where the famous Los Apaches Restaurant later resided. (The restaurant is now closed.) Wolf was educated in San Antonio, spoke fluent Spanish as well as some German, and eventually taught electronics at Kelly Air Force Base. And it was around 1948 he remodeled his liquor store and opened the Rio Record Shop that housed the Wolf Recording Company and became “Home of the Rio Record” for the next decade.

In 1956 Wolf met Genie Miri and they got married on June 23, 1960. For the next three years Wolf, who was an excellent pilot, also operated an aviation business and took his wife on many trips. The couple worked together at the record shop until Wolf’s death on October 10, 1963. His wife continued to operate the shop for many years after but the label stopped recording activities in 1963, except for Rio No. 455 by Luis Gonzales which was issued in July of 1964 and saw its last re-pressing in 1968. In the 1970s I met Genie Wolf at the old location of the store.When I inquired as to which local conjunto impressed her the most, she suggested I record Flaco Jimenez, whom she felt had a lot of charisma. In 1991, I purchased all the masters and contracts of Rio Records from Mrs. Wolf for Arhoolie.

Most Rio 78s and 45s are exceptionally rare because sales were small due either to limited distribution or to the fact that no one heard or wanted them. Wolf did not believe in promotion, even going so far as to charge radio stations for copies instead of paying them to play his records, as was the general custom at the time! And he was cautious in production, judging by entries in his ledger book, which shows orders and sales for Rio releases. For example, in August of 1956 he initially ordered 300 copies of No. 374 by Los Caminantes (200 78s and 100 45s). However, that recording of “Mis Penas” backed by “Borrar Quisiera,” both written by Henry Zimmerle, became a popular item and re-pressings were frequent but in small quantities ranging from a low of 25 to a high of 110, eventually resulting in a total of 2820 units, combined 78s and 45s, being pressed by 1961. In contrast, the initial pressing order in 1960 for the 45rpm single Rio No. 441 by Los Navegantes was for 150 units, and the item was never re-pressed.

In addition to being hard to find, these recordings were primitive; and as the competition grew, most artists turned to more professional labels and producers including Jose Morante in San Antonio and Falcon and Ideal records in South Texas. For authenticity however, no other label or producer captured pure cantina music the way Hymie Wolf did on his Rio recordings.

̶Chris Strachwitz

This label history was adapted from line notes originally written by Chris Strachwitz for the 1994 Arhoolie Records compilation Tejano Roots: San Antonio's Conjuntos in the 1950s (Ideal/Arhoolie CD-376).