History Revisited: "Los Tigres del Norte at Folsom Prison"

In late 2019, Los Tigres del Norte released a live album that marked a milestone in their storied career. The two-CD set captured the band’s historic performance at Folsom State Prison, staged to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the legendary concert by country singer Johnny Cash at the same notorious penitentiary. The Tigres event was also filmed for a Netflix documentary, released along with the album on Mexican Independence Day.

In late 2019, Los Tigres del Norte released a live album that marked a milestone in their storied career. The two-CD set captured the band’s historic performance at Folsom State Prison, staged to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the legendary concert by country singer Johnny Cash at the same notorious penitentiary. The Tigres event was also filmed for a Netflix documentary, released along with the album on Mexican Independence Day.

Within weeks, the music industry came to a halt after the COVID-19 pandemic hit and hobbled the economy. Touring was cancelled for most of 2020, depriving the band of key exposure. By December of that year, Los Tigres released a follow-up studio album, a traditional tribute to Vicente Fernandez. The Folsom album quietly took its place in the band’s prolific discography, now approaching 60 albums since 1968.

I think it’s time to revisit the band’s historic prison concert, especially for those who may have overlooked it. Below are the liner notes I wrote for the album release on Fonovisa Records, part of Universal Music Latin Entertainment. This is the first time the English version has been published, since the CD included only the Spanish translation.

My original text, with slight modifications, is reprinted here with kind permission of the project’s executive producers, Zach Horowitz and Los Tigres. The band of brothers, in conjunction with the Arhoolie Foundation, helped launch the Frontera Collection through a grant from the Los Tigres del Norte Foundation to the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center.

Los Tigres at Folsom Liner Notes ![]()

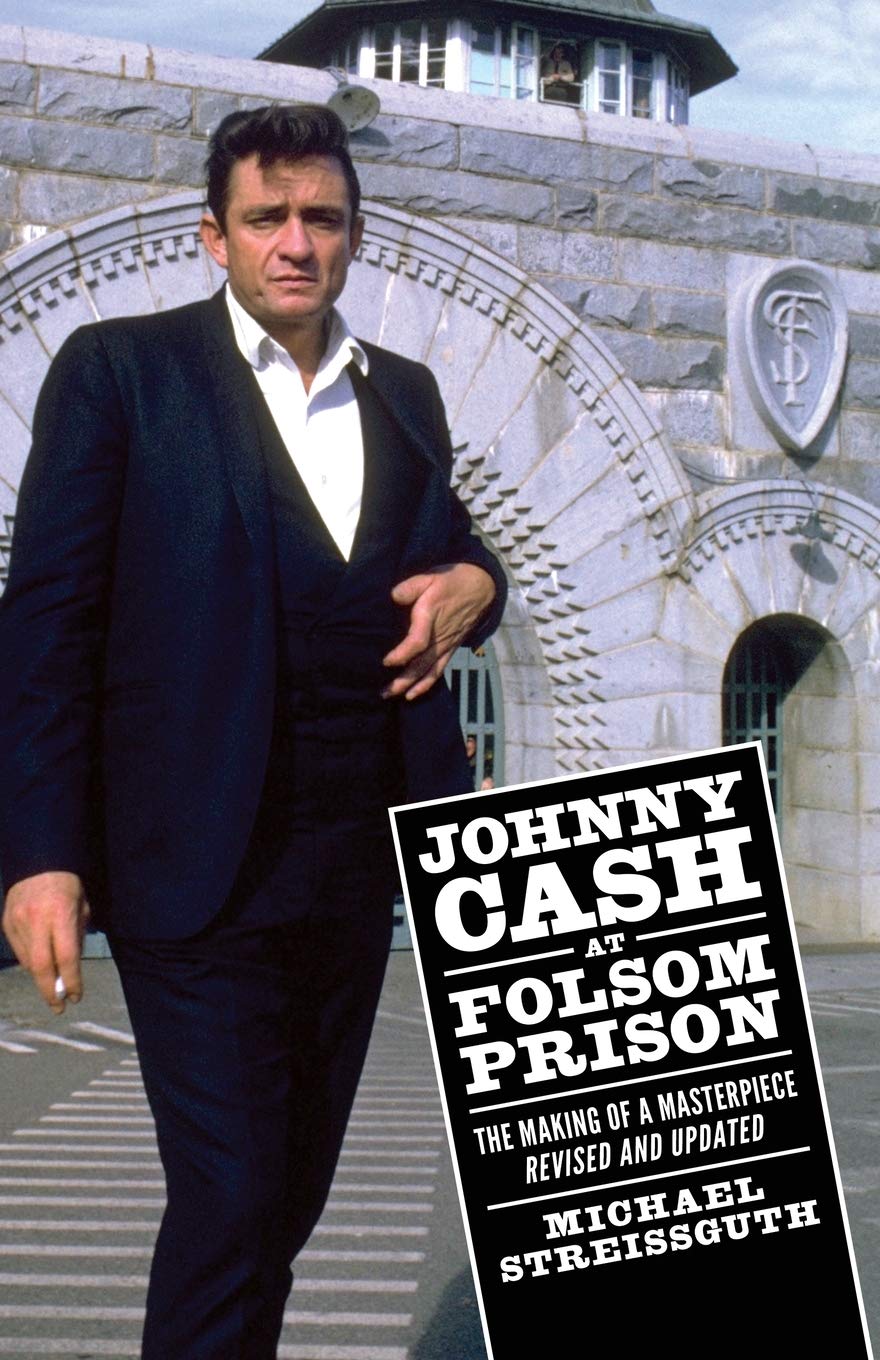

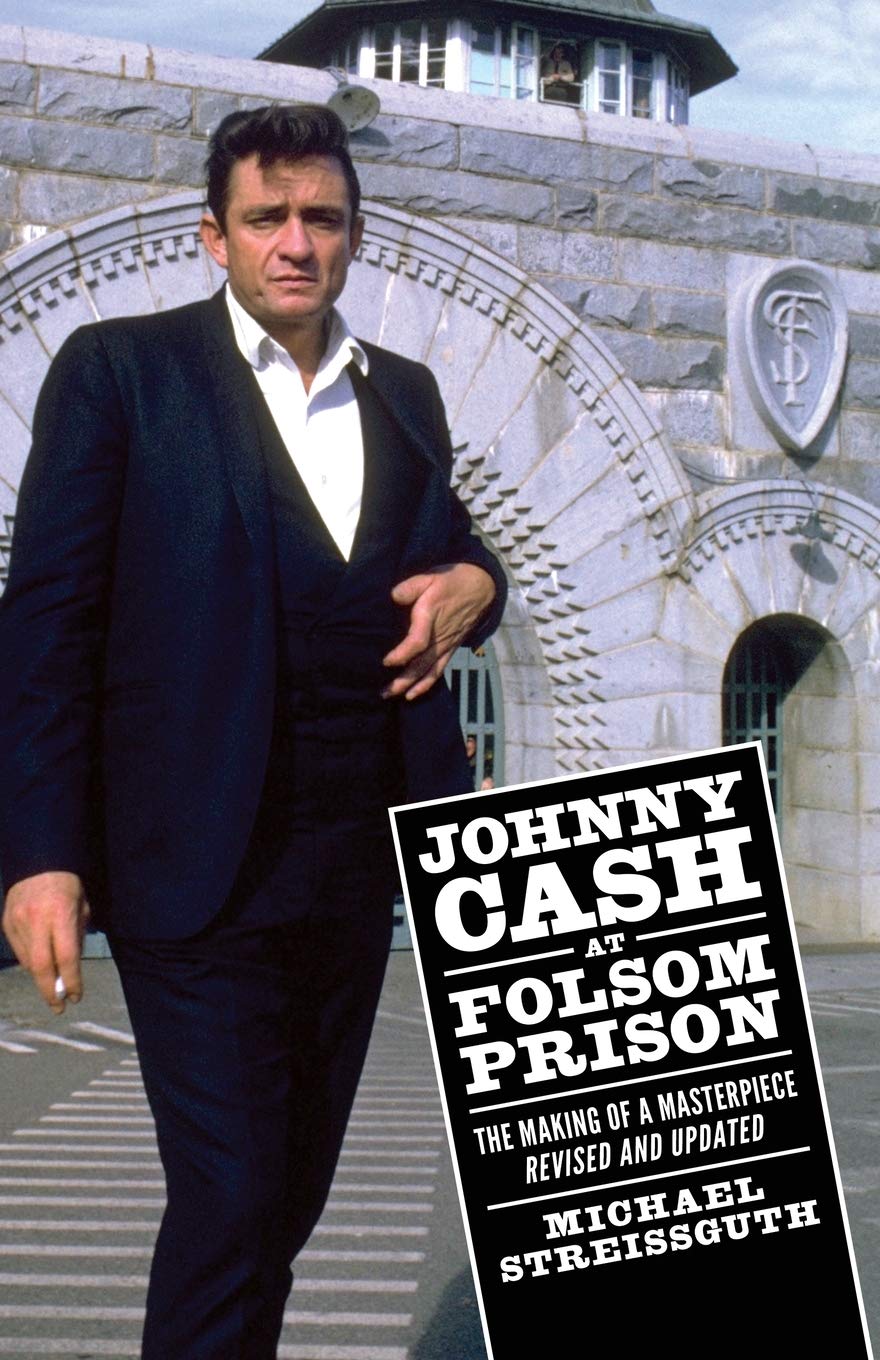

When Johnny Cash performed his landmark live concert at Folsom State Prison in 1968, Los Tigres del Norte were new immigrants to this country, with only dreams of being recording stars. At the time, these performers – an iconic but troubled American singer and an ambitious but unproven Mexican conjunto – were separated by a battery of natural barriers. They spoke different languages, worked in different genres, came from different generations, and lived on opposite sides of a historically troubled border.

Yet, half a century later, fate would cause their careers to converge, uniting them musically and spiritually on common ground. In 2018, Los Tigres memorialized the 50th anniversary of Cash’s prison performance with a concert of their own at Folsom, filmed for a Netflix documentary and recorded live for an album, both entitled “Los Tigres del Norte at Folsom Prison.”

Although scores of artists expressed interest, Los Tigres is the only act authorized to perform at Folsom for the 50th anniversary of Cash’s historic appearance. This soundtrack album is the first live recording from inside the prison walls since Cash recorded his smash album, “At Folsom Prison,” the year Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King were assassinated.

The spirit of the late Johnny Cash, who passed away in 2003 at age 71, was evoked from the very start. Los Tigres opened their two-hour set with a Spanish version of Cash’s original opening song, “Folsom Prison Blues,” translated for the first time with the help of Ana Cristina Cash, the singer’s daughter-in-law, a Cuban-American musician now living in Nashville.

The band offered other references in deference to the unique persona of the Man in Black, as Cash was known for his trademark attire. When Los Tigres appeared on stage –brothers Jorge, Hernán, Eduardo, and Luis Hernández, and their cousin Oscar Lara – all the band members were wearing black. Then, echoing Cash’s signature line (“Hello, I’m Johnny Cash”), the band in unison greeted the gathered inmates with a similar salute: “Hola, nosotros somos Los Tigres del Norte.”

Those are symbolic tips-of-the-hat. But a deeper artistic sensibility also binds Cash and Los Tigres, despite those formidable barriers.

“Personally, I identify with him because of his desire to give voice to our people,” said Jorge Hernández, accordionist and lead singer of many of the group's greatest hits. "We are intertwined through the music we play, both representing our communities."

Did you notice that choice of words? “Our people,” Hernández said. Not separate audiences. Not white and brown, north and south, English and Español. No, they are both singing to the same audience, from the same tier of their respective societies. The poor and the powerless, the forgotten and unforgiven, the underappreciated and overworked, the outcast and the voiceless.

Los Tigres could have authentically sung a Spanish version of Cash’s “Man in Black,” with the line, “I wear the black for the poor and the beaten down / Livin' in the hopeless, hungry side of town.”

For Los Tigres, however, the verse would have to include the much-maligned immigrant, whose plight they passionately express, whose rights they unfailingly defend. The group has spent the past half-century telling their untold stories, singing about their loves and losses, tragedies and triumphs. For their advocacy, they earned the nickname Los Ídolos del Pueblo, from adoring fans.

At first glance, Cash and Los Tigres seem unlikely musical allies. Fifty years ago, few would have predicted their careers could ever intersect.

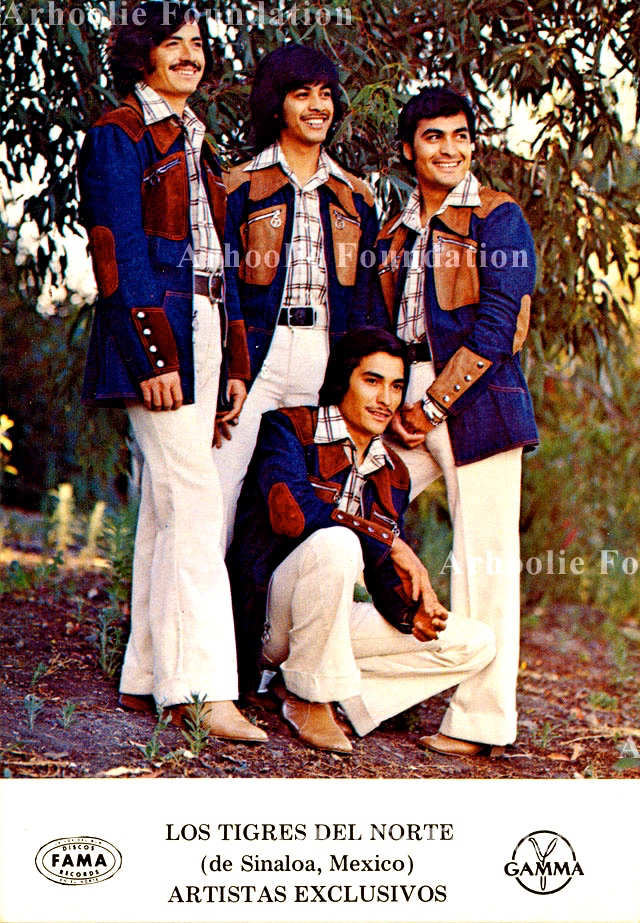

Cash launched his country music career in 1955, with his first single recorded on Sun Records, the fabled Memphis label that initially signed Elvis Presley. At that time all but one of Los Tigres weren’t even born. Like Cash they grew up poor, raised in Rosa Morada (Purple Rose), Sinaloa, a rural hamlet so remote the boys had to learn songs by word of mouth because there was no radio, no phonographs, no sheet music.

By the mid-60s, Cash had recorded 20 albums for Columbia Records, and was deep into the drinking and drug use that would stall his career. Meanwhile, the Hernández boys were performing for tips to help pay medical bills for their father, who had suffered a disabling work accident. The band was so informal, it didn’t even have a name.

For both Cash and Los Tigres, 1968 would be a pivotal year. While the band of youngsters was being born professionally, the veteran singer was suddenly reborn.

Cash had overcome his professional malaise and was riding high again after the success of his live Folsom album. The now classic single, “Folsom Prison Blues,” hit No. 1 on the country charts and earned a Grammy for best country vocal performance. He went on to use his renewed notoriety to advocate for prison reform.

Cash had overcome his professional malaise and was riding high again after the success of his live Folsom album. The now classic single, “Folsom Prison Blues,” hit No. 1 on the country charts and earned a Grammy for best country vocal performance. He went on to use his renewed notoriety to advocate for prison reform.

Los Tigres, meanwhile, had lucked into the biggest move of their nascent career – relocating permanently to the U.S. and settling in San Jose, California. Initially, they came on a 90-day work visa, but never moved back.

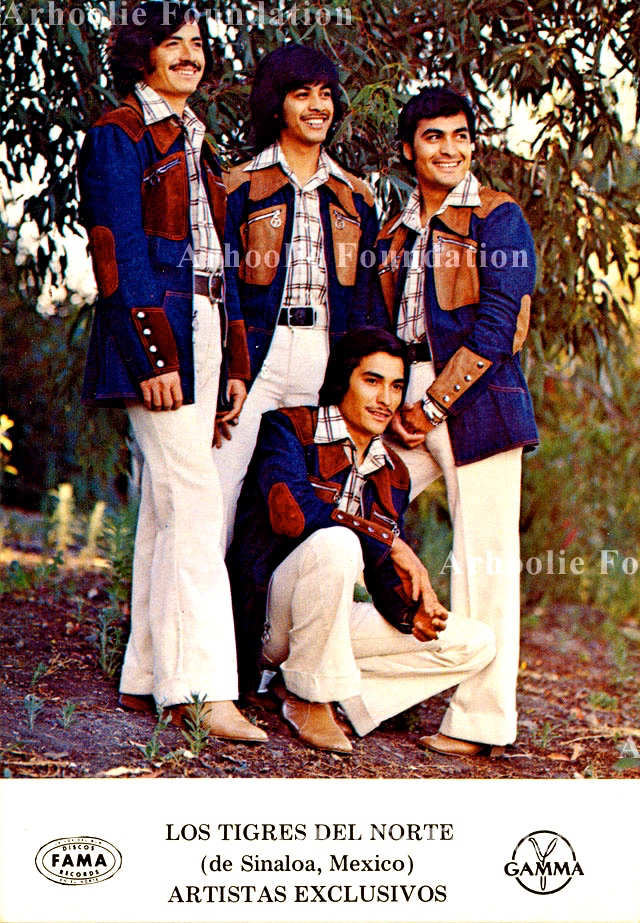

The early years would be a struggle for the band, but at least now they had a name. They were christened by a friendly immigration agent when crossing the border for their first U.S. appearance, coincidentally at Soledad State Prison. The agent asked for the group’s name, but they still didn’t have one. So he dubbed them “the little tigers of the north,” impressed by their go-get-‘em attitude. At the last minute, the helpful agent wrote “Los Tigres del Norte,” allowing them time to grow into the name as adults, if they were to last that long.

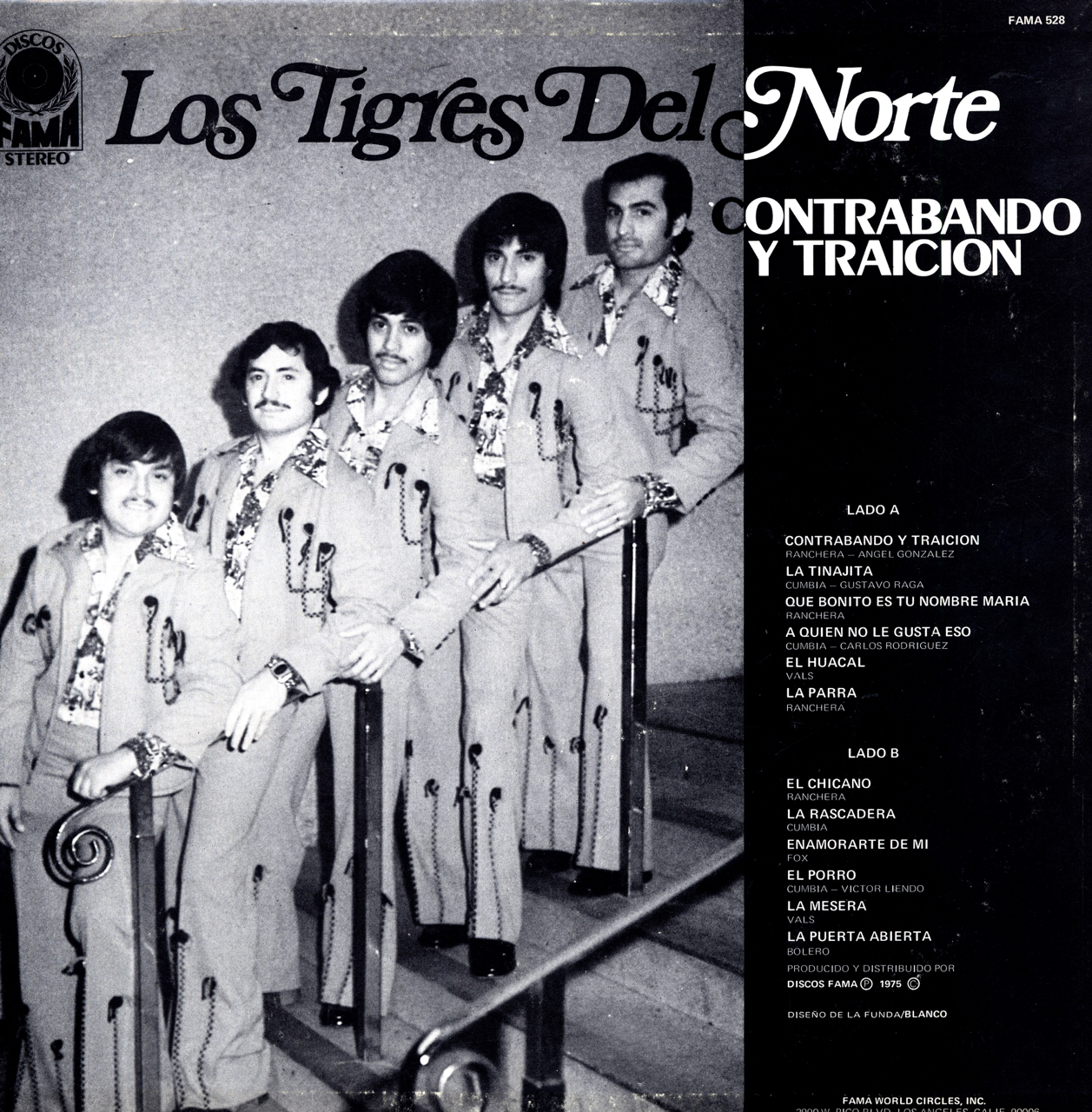

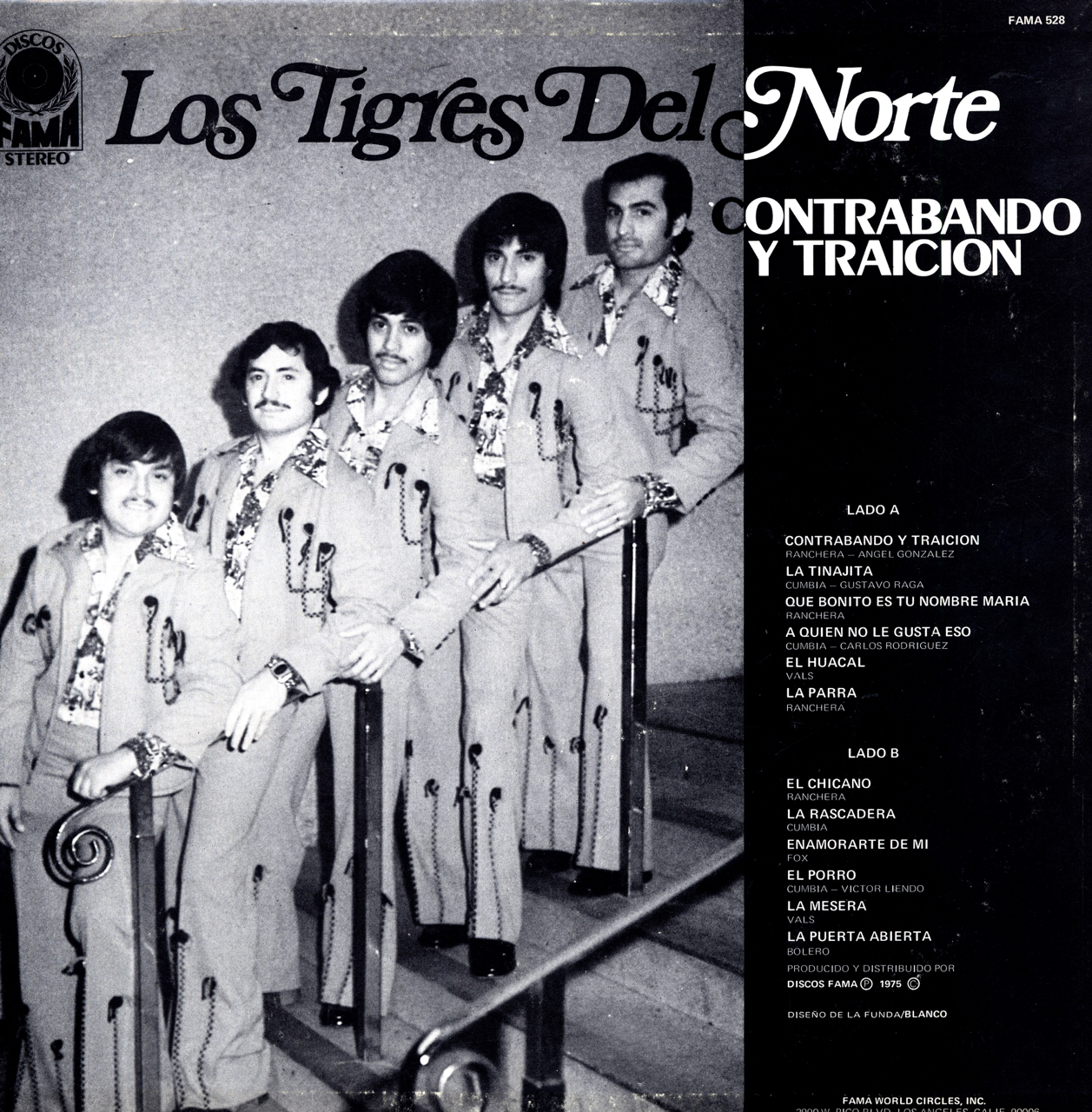

In San Jose, they soon signed with a small local label, Fama Records that was also just getting started. Within a few years, Los Tigres scored their first big hits, “Contrabando y Traición” and “La Banda del Carro Rojo,” rocketing them to international fame and kicking off the modern narco-corrido trend.

Los Tigres have been riding high ever since. Over the next five decades, they sold tens of millions of albums, toured around the world, and emerged as the pre-eminent norteño band in the business and one of the most influential Latin bands of all time. Through all their success, they’ve never lost touch with their community. “For us it’s all about the special connection we feel with our audience. We tell their stories in our music.” said Hernán Hernández, who sings lead vocals and plays bass.

The group’s most remarkable achievement has been its staying power. They have remained steadily at the top of their field, resisting fads and fickle pop tastes. So when they arrived at Folsom, they had nothing to prove, or to gain necessarily. When they passed through those forbidding gates and stepped inside the massive stone walls of the 138-year-old prison, they had a social mission in mind, not a career calculation.

“I never felt afraid to be inside the prison, but the experience of being there affected me emotionally,” said Eduardo Hernández, who sings vocals and plays accordion, alto saxophone and bajo sexto. “I heard stories from the prisoners that touched my heart deeply. For them, the experience is a way of releasing pent-up feelings, or perhaps the regret and guilt they keep inside.”

The prison population has grown exponentially in the past 50 years. And the percentage of prisoners who are Latinos has also exploded. In 1968, the year Cash played at Folsom, there were some 28,000 total inmates in California. Today, that number has more than quadrupled to 130,000. Back then, the inmate population was mostly white. Today, Latinos make up the largest share, over 43 percent, of those incarcerated in California’s state prisons, up from 30 percent in 1990.

This dismal demographic is one of the reasons the band wanted to do this project—to help generate a dialogue around the important issue of Latino incarceration.

Not surprisingly, the audience for the two Folsom concerts, 50 years apart, went from mostly white to overwhelmingly Latino. And there were other differences as well.

When Cash played two back-to-back shows on January 13, 1968, the weather was chilly, the concert was held indoors in a cafeteria, and the atmosphere was tense because prisoners had recently taken a guard hostage. Armed guards kept close watch on the prisoners, who were told not to stand during the show.

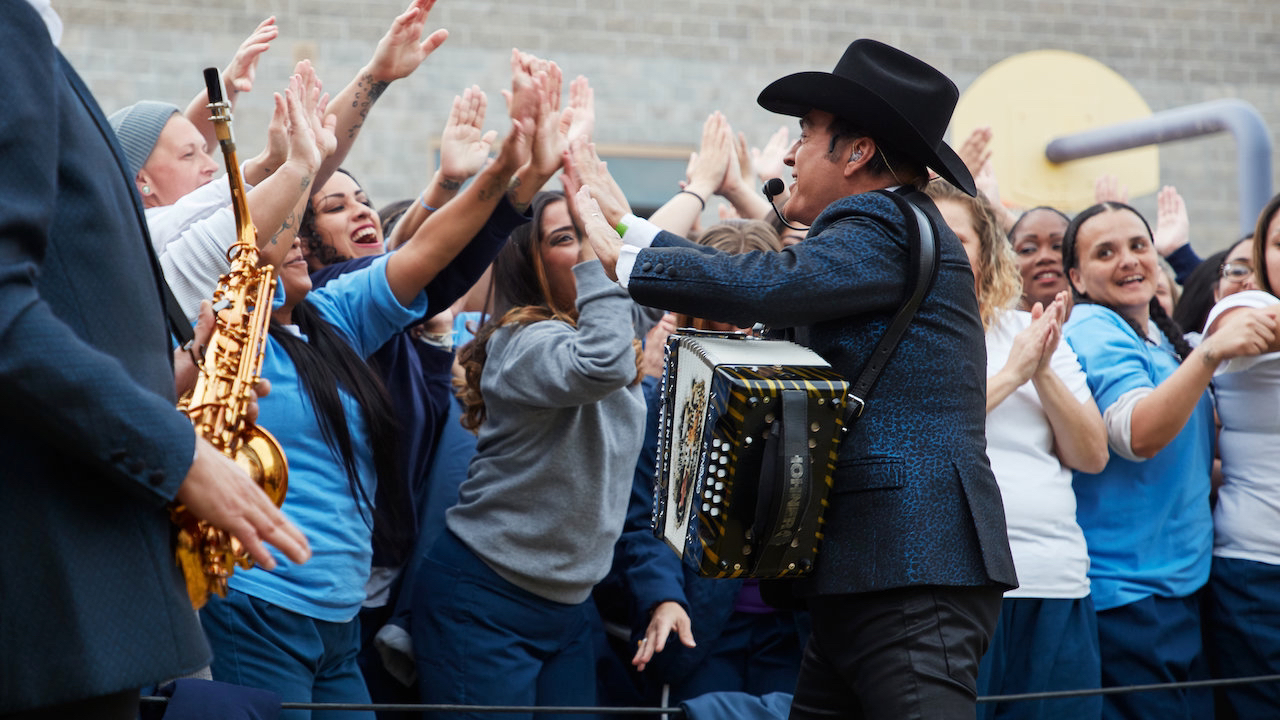

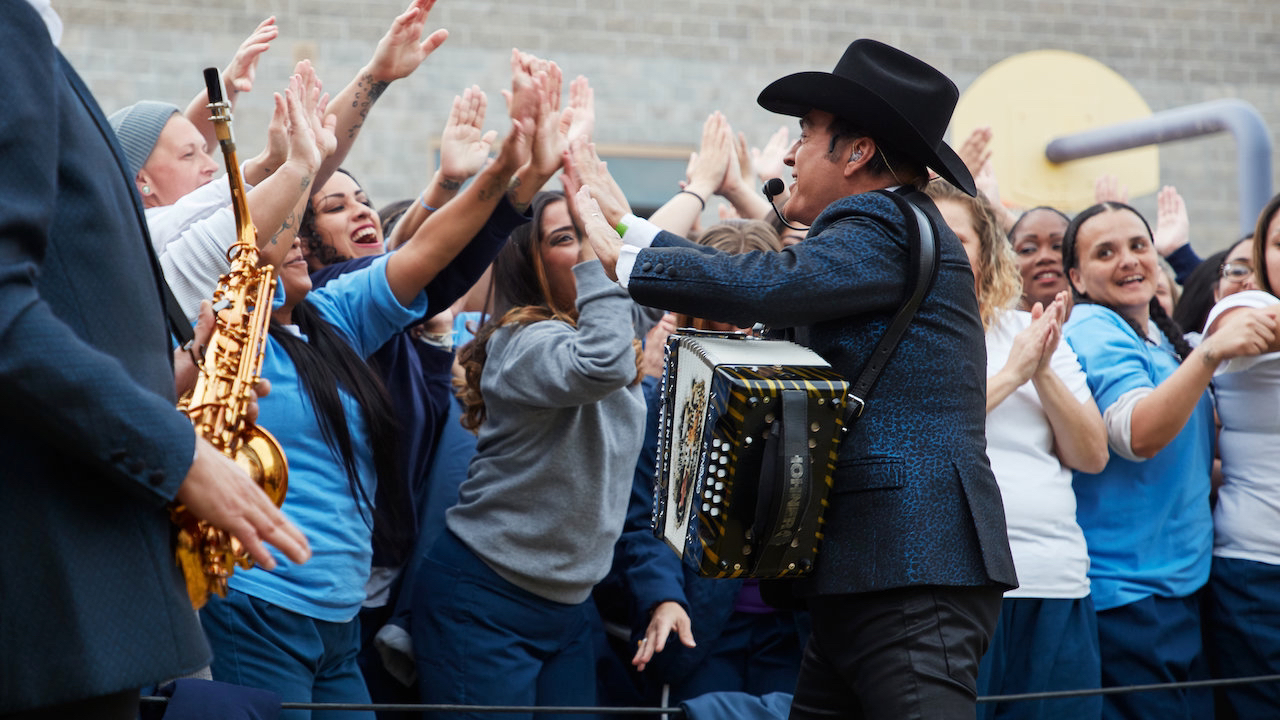

Conditions were noticeably better for Los Tigres who performed on two consecutive days April 17 and 18, 2018. The weather was sunny and warm, the concerts were held outdoors, and the atmosphere was much more relaxed. For Los Tigres, inmates were not only allowed to stand, but they had the freedom to dance and sing along with abandon.

For the men’s concert, the band also enjoyed an impressive backdrop. The stage was set up in front of Greystone Chapel, immortalized by Cash who performed a song, written by a Folsom prisoner, about the imposing Gothic structure. Los Tigres also used the chapel to meet and mingle with some of the inmates featured in the documentary.

One other important element distinguished the Tigres event – a female audience. On the second date, Los Tigres played for female prisoners at a separate, smaller facility, which did not exist until 2013. The women’s show was so festive it had the feel of a backyard party. Since the women at Folsom are considered lower risk than the men, the band was permitted to play at ground level, face to face with the female fans.

The women responded gleefully. They smiled, sang along, and danced, both in sync like a chorus line in front, or as couples in the back.

The women responded gleefully. They smiled, sang along, and danced, both in sync like a chorus line in front, or as couples in the back.

For a moment, it was easy to forget they were in prison.

The state did impose one major restriction: No songs that appear to encourage or glorify crime, violence, and drug dealing, or that might even inadvertently undermine the prison’s security and rehabilitation efforts. For Los Tigres, that eliminated some of their biggest hits, especially those famous narco-corridos that fans still love.

But the rule prompted a creative solution that provided the show with a brilliant structure. The band selected songs based on the stories of inmates who had been interviewed for the documentary a few weeks earlier. There was such a wealth of material in their repertoire, so many relevant songs, that the selections seemed tailored to every individual story.

Early in the set, the band sings “Jaula de Oro,” about a distressed father who makes money in the U.S. but loses moral authority over his family. At the same time, we hear inmate Juan Fernandez talk about starting his life of crime at 19, despite the example of hard work set by his upright father. And he doesn’t know why he lost his way.

“It was an unforgettable experience just speaking with the prisoners, listening to their stories about why they’re there, and hearing them say how happy it made them to see us,” said Hernán Hernández. “One of those prisoners told me that when he hugged me, he felt he was hugging his brother, because he said I look like him. I felt joy being there, and it made me think of the importance of family and friends. Because those prisoners don’t know when they’ll ever have another opportunity to return to their loved ones.”

“It was an unforgettable experience just speaking with the prisoners, listening to their stories about why they’re there, and hearing them say how happy it made them to see us,” said Hernán Hernández. “One of those prisoners told me that when he hugged me, he felt he was hugging his brother, because he said I look like him. I felt joy being there, and it made me think of the importance of family and friends. Because those prisoners don’t know when they’ll ever have another opportunity to return to their loved ones.”

These songs are like parables. Unlike Cash’s outlaw image, Los Tigres have always focused on morality tales, especially in their songs about drugs and violence. They don’t judge, they try to inspire. They understand the lives of these prisoners, the pressures they face, the mistakes that brought them here, consumed with regret.

You can hear those stories on this album in the inmates’ own voices, via interview clips interlaced between tracks. Neither the performances alone nor the interviews alone have the power they pack together, merged as a single piece of art. The emotional impact is palpable in the documentary and reflected on the record.

The result is a work that feels natural and seamless. But making it a reality was far from smooth sailing.

The nearly three-year struggle to stage the live event would make a riveting documentary of its own. Along the way, there were approvals and rejections, high hopes and disappointments, promises made and broken. Given the state policy against the release of concert films and albums recorded inside California prisons, getting a green light would require the help of powerful political leaders – former Congressman Howard Berman, then-Secretary of State and now U.S. Sen. Alex Padilla, and the offices of two California Governors, Jerry Brown and Gavin Newsom.

The relentless driving force behind the effort has been Zach Horowitz, former President & COO of Universal Music, who partnered with Los Tigres to produce the project. Oscar-winning film composer and 18-time Latin Grammy winner Gustavo Santaolalla, a legend in his own right, was tapped as music producer and offered creative advice along the way. He and his longtime partner Anibal Kerpel, the album’s co-producer, were ensconced in a cramped remote studio truck at Folsom, with so many cables, dials, and gauges it resembled a space capsule.

To bring the project to fruition, Horowitz found a key ally in state prison chief Ralph Diaz, who retired last year as Secretary of the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, then the highest-ranking Latino in the agency’s history. Diaz also happens to be a lifelong Tigres fan, ever since he was a boy at his grandmother’s side, growing up in the San Joaquin Valley.

Rehabilitation is the key that unlocked Diaz’s cooperation. It’s a priority for the prisons, and completely compatible with the message of Los Tigres.

“The band came to us with a unique proposal. They didn’t want to just play a concert; they wanted to hear from the inmate population and send a specific message through their music,” Diaz said in an interview for a state newsletter. “While this concert could have only been about entertainment value, it became clear that their message of hope and rehabilitation was in line with ours.”

Halfway through the set, the band invited one of the Folsom inmates, Manuel Mena, on stage to sing and play accordion with them. He’s a former professional musician serving a 36-year to life sentence for killing a man in a dispute after one of his shows. It’s a highly emotional moment, not just for Mena, but for the band and everyone in the audience. The song he sings with the band is “Un Día a la Vez,” a plaintive cry for divine help to survive this malevolent world, “one day at a time.”

Halfway through the set, the band invited one of the Folsom inmates, Manuel Mena, on stage to sing and play accordion with them. He’s a former professional musician serving a 36-year to life sentence for killing a man in a dispute after one of his shows. It’s a highly emotional moment, not just for Mena, but for the band and everyone in the audience. The song he sings with the band is “Un Día a la Vez,” a plaintive cry for divine help to survive this malevolent world, “one day at a time.”

The sight of a fellow convict on stage with these superstars sparked a cheer from the men, gazing up at the stage from the recreation yard. In this often-hostile environment where prisoners learn to watch their backs or perish, the men seemed to let down their guard and celebrate a special moment for one of their own.

"We are the forgotten of society," says Mena, who was born in Tijuana. "And to have the privilege of experiencing something like this? Well, it means we haven't been completely forgotten. It means there's someone who remembers us, someone who gives us the strength to keep going, the strength to keep moving forward."

– Agustín Gurza

Tags

Images