Store Stickers: Windows on a Lost Way of Life

A true record collector is more than a mere music aficionado. Collectors are also part historians, part archivists, part treasure hunters, and part detectives. They look at records like archeological artifacts, analyzing them for clues to a particular culture and way of life, in a specific time and place.

A true record collector is more than a mere music aficionado. Collectors are also part historians, part archivists, part treasure hunters, and part detectives. They look at records like archeological artifacts, analyzing them for clues to a particular culture and way of life, in a specific time and place.

Even the common price sticker, for example, can offer a tantalizing glimpse into the life of a record, especially one that keeps circulating, passed lovingly (one hopes) from hand to hand. It tells you where that record made a stop on its road from manufacturer to market. And it allows you to imagine the details of that retail sojourn.

“The store sticker for me serves as a mental map of where Mexican culture was bought, sold, and treasured by many immigrants,” wrote my colleague Juan Antonio Cuellar in a recent blog for the Facebook page of the Arhoolie Foundation Frontera Collection. “I love finding them and doing a Google map search for their location and wonder what life was like back then for Raza looking to cop the latest 78 by the hottest dueto of the time.”

For the past several years, Cuellar has been the lead engineer in the massive task of transferring the Arhoolie Foundation’s physical recordings to digital files, which now constitute the Frontera Collection’s online archive. He has painstakingly reviewed thousands of discs, one side at a time, placing them on a turntable with specialized equipment to make the analog-to-digital transfers.

In that process, he came across old 78-rpm records from the first half of the 20th century that featured retail stickers on the labels themselves. Cuellar considers these old-fashioned promotional emblems to be precursors of what are known as “hype stickers” in the modern record industry.

Hype stickers are normally affixed to the front cover of an album, either by the manufacturer pushing a certain hit single, for example, or by the retailer pushing a sale price with its logo. Nowadays, more sophisticated audiophile releases use hype stickers to advertise the top-grade technical aspects of the recording.

However, single records from the 78-rpm era did not come enclosed in sturdy outer sleeves with photos and liner notes. In the old days, the brittle discs came in simple paper sleeves with a round opening in the center exposing the label. So retailers placed their promotional stickers directly on the label itself.

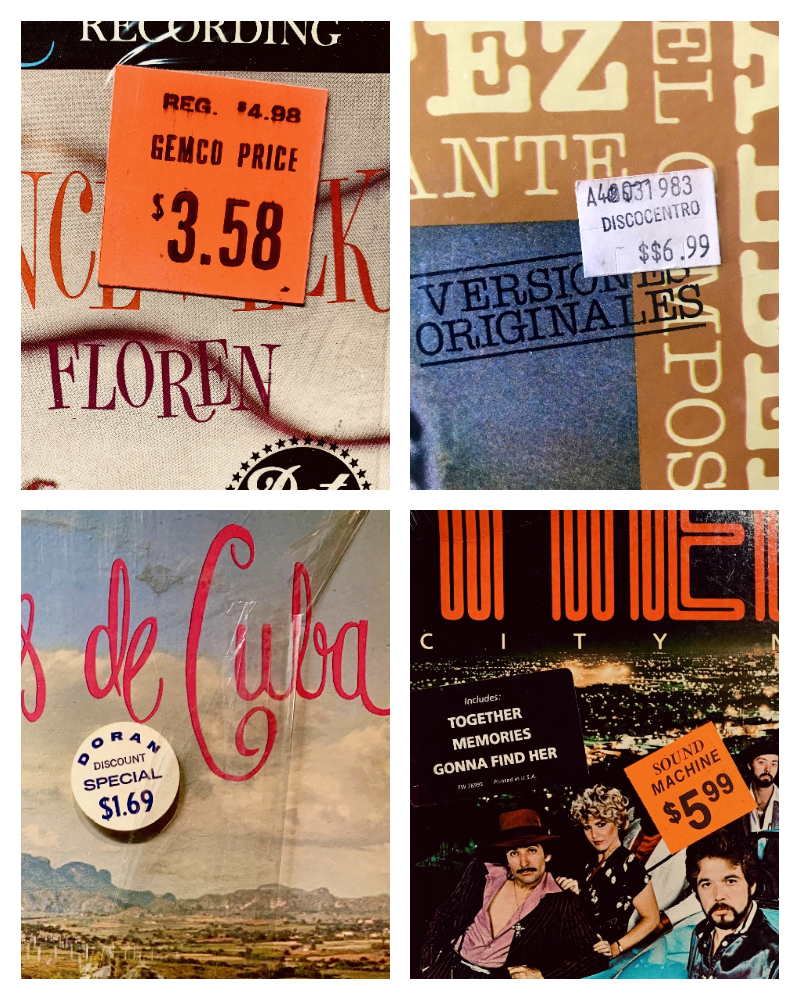

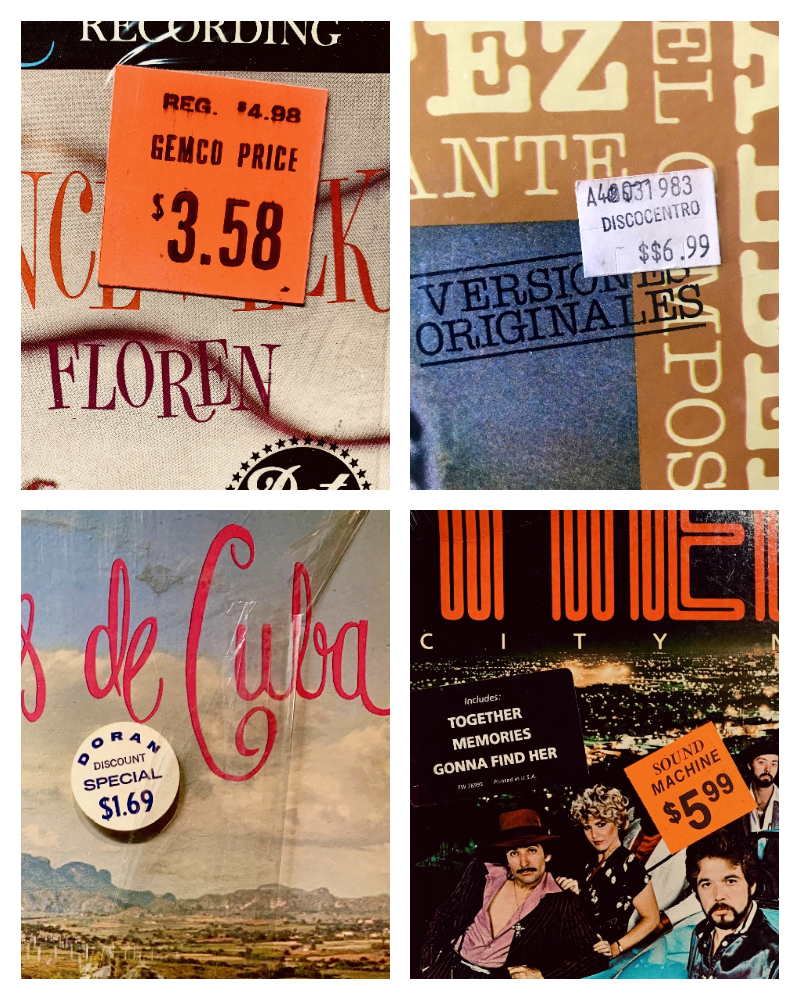

Nowadays, simpler retail stickers are commonly used to advertise the price. But even these price stickers can have personal meaning for collectors. For instance, my father shopped religiously for records on the weekends in San Jose, California, during the 1950s and 1960s, when modern record distribution was in its infancy. In those days – before the advent of big record store chains like Tower, Sam Goody, The Wherehouse, and Music Plus – records were commonly sold in large department stores that offered a selection of top sellers in small music sections.

My father discovered that good deals could be had in popular discount department stores (pre-Costco), such as the now-defunct White Front and Gemco. Plus, they carried an ample selection of Mexican records, which was the big lure for him.

For us, it was always torture when we’d be in the car after Mass and he’d say, “I’m just going to stop at the Gemco for a minute.” We knew what that meant – an interminable, exasperating wait for him to browse through every record, picking them up one by one, reading the liner notes, and deciding on his haul for the week, which often included duplicates of records he already.

My father’s record-collecting ways had a powerful impact on me in two very different ways. Being forced to wait for his long shopping trips turned me into an extremely impatient man. But being exposed to his ample collection at home made me an admirer of Mexican culture and an aficionado of recorded music, not just records but record-playing equipment. Dr. Gurza bought the best consoles at the advent of stereo sound, and regaled visitors with Hi-Fi demonstration records that had bongos ping-ponging on speakers from left to right.

Recently, I recently bought used records with those old price stickers from defunct discount stores still on them, and I wonder if my dad had thumbed through these very copies. Even closer to home are the used records I’ve found with a sticker that reads “DiscoCentro.” I recognize it because I owned and operated that store in the 1980s in East L.A. Decades later, I’m buying back the used records I once sold as new, more proof that collectors can be obsessive.

My father also loved to shop at Sears, mostly for tools and camping equipment. Later, before I had my own shop, I worked for a large national record distributor that serviced music departments in chains like Sears, Woolworth’s, and K-Mart. By then, Sears had been branding itself as an exclusive music seller for decades. Since the early 1900s, Sears issued its own record labels, with names such as Harvard, Oxford, and Silvertone, which were licensed from major labels, including Columbia, Decca and RCA, and sold through its stores and famous catalog. Montgomery Ward went a step further in overt branding, creating a record label with its own name on it.

The mass-market nature of these national labels, however, deprives them of the singular charm that makes the private sticker from independent retailers so interesting, and potentially revealing.

As a fellow store-sticker obsessive, here are my observations on a few examples from Cueller’s blog.

El Arte Mexicano, Chicago, Illinois

Cuellar highlights this retailer in his blog, noting the multi-faceted interests of its owner, identified on the label as Ignacio M. Valle. Cuellar discovered in his research that Valle, in keeping with his store’s name, also sold “Mexican art in clay, wood, leather, feathers, glass, cloth, rugs, hats, furniture, etc.” But Valle was more than just a merchant, Cuellar notes. He was also a prolific composer who “managed to write over 50 songs that include many historically significant two-part corridos.”

Cuellar highlights this retailer in his blog, noting the multi-faceted interests of its owner, identified on the label as Ignacio M. Valle. Cuellar discovered in his research that Valle, in keeping with his store’s name, also sold “Mexican art in clay, wood, leather, feathers, glass, cloth, rugs, hats, furniture, etc.” But Valle was more than just a merchant, Cuellar notes. He was also a prolific composer who “managed to write over 50 songs that include many historically significant two-part corridos.”

Valle’s red, rectangular store sticker promotes music sales with a generic description in all-caps: “REPERTORIO MUSICAL.” Although the print is partially smudged, the address and proprietor’s name are still legible. It was located on Halsted Street across from what is now the University of Illinois at Chicago, which was established in the early 1960s.

Today, Cuellar notes, little is known about the store’s songwriting proprietor.

“There is still not much written about Valle,” he writes, “but his contribution to the Mexican-American experience should be documented and celebrated with much more than finding his store sticker on a 78.”

Librería Hispano-Americana, Fresno, California

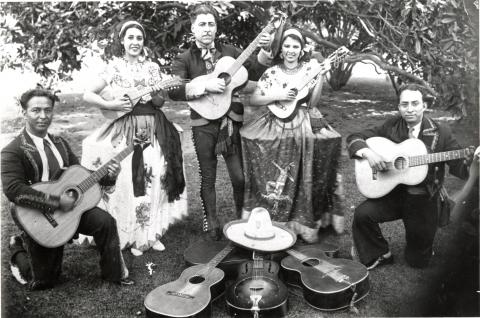

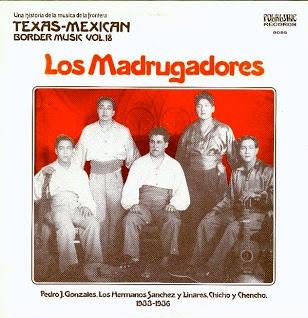

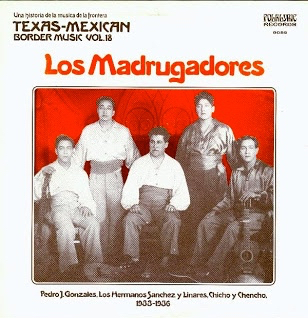

This large sticker, eclipsing the entire label name, reveals how records were sold in retail stores along with other merchandise. In this case, Fresno’s Hispanic-American bookstore also offered newspapers, popular illustrated magazines, and stationary stuff, described as “items of the desk.” I assume the name “Izquierdo y Martinez” refers to the ownership, though it’s unclear whether it’s a partnership or sole proprietor. The store’s location in California’s central San Joaquin Valley suggests it catered to the Mexican farmworkers who settled in the rich agricultural region. It’s no coincidence the record itself is by the hit group Los Madrugadores (The Early Risers) who appealed to the working-class, immigrant community.

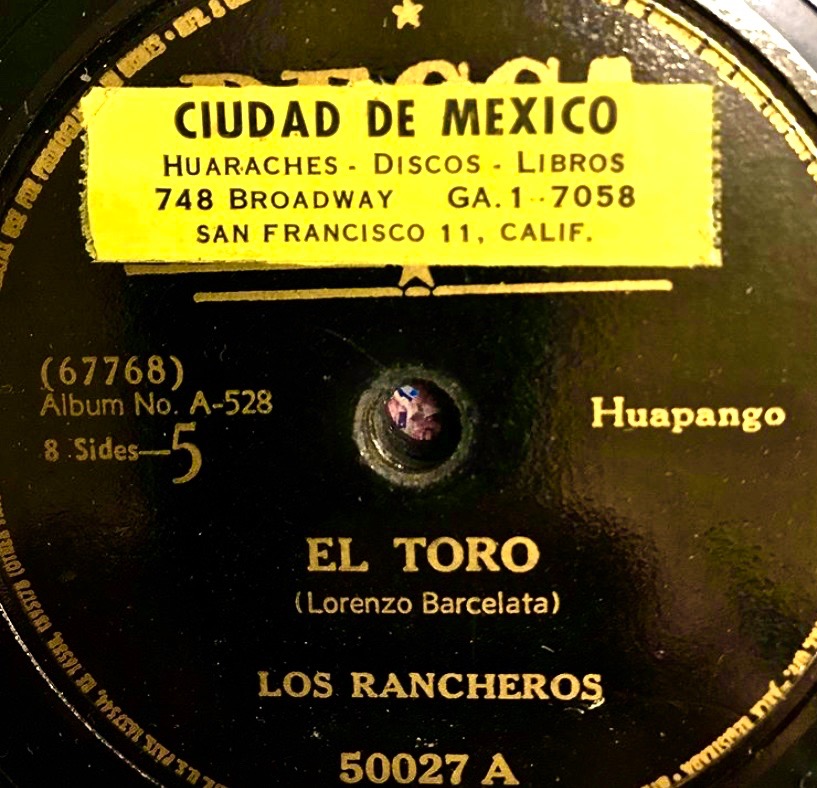

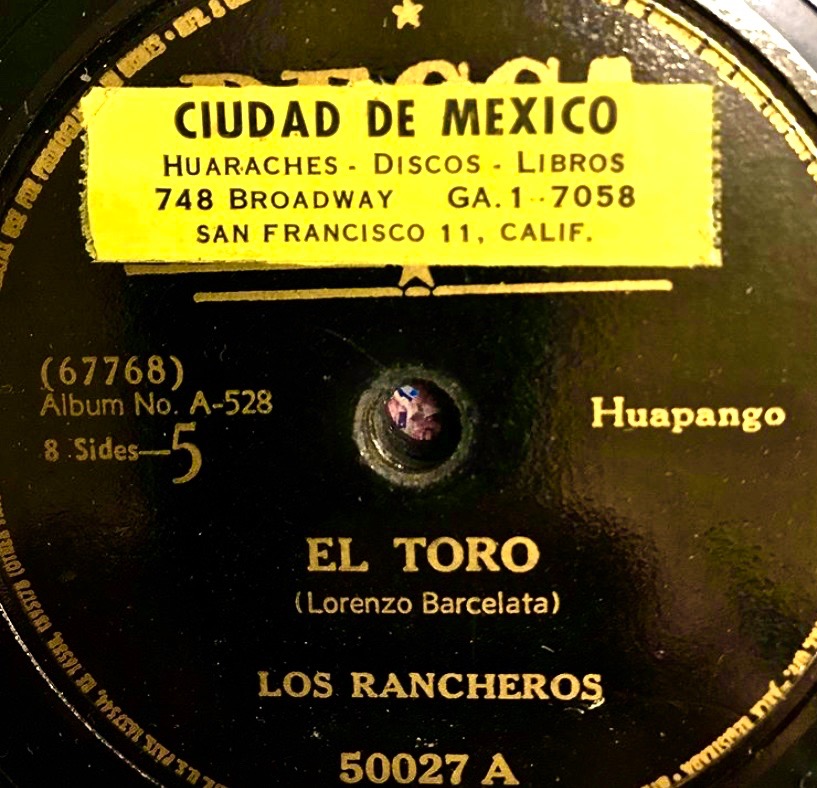

Ciudad de Mexico, San Francisco, California

This store was located in San Francisco’s famed North Beach district, just blocks from where beat poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti would establish his landmark City Lights Bookstore in 1953. The record shop betrayed a certain urban aspiration by naming itself after Mexico’s cosmopolitan capital. Still, it wasn’t above selling records and books along with huaraches, the humble, pre-Colombian Mexican sandal. (Most recently, the storefront at 748 Broadway was occupied by a vintage clothing store, The Dressing Room.) Ciudad de Mexico’s rectangular, yellow sticker also covers the label name, though the word Decca appears to peek over the top. The recording is a huapango by Mexico’s prolific composer from Veracruz, Lorenzo Barcelata. Note that the track is identified as the fifth of eight sides, suggesting that the disc was part of a bound, four-record set (one song per side), a merchandising practice that gave rise to the term “album” to describe a collection of recorded music.

This store was located in San Francisco’s famed North Beach district, just blocks from where beat poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti would establish his landmark City Lights Bookstore in 1953. The record shop betrayed a certain urban aspiration by naming itself after Mexico’s cosmopolitan capital. Still, it wasn’t above selling records and books along with huaraches, the humble, pre-Colombian Mexican sandal. (Most recently, the storefront at 748 Broadway was occupied by a vintage clothing store, The Dressing Room.) Ciudad de Mexico’s rectangular, yellow sticker also covers the label name, though the word Decca appears to peek over the top. The recording is a huapango by Mexico’s prolific composer from Veracruz, Lorenzo Barcelata. Note that the track is identified as the fifth of eight sides, suggesting that the disc was part of a bound, four-record set (one song per side), a merchandising practice that gave rise to the term “album” to describe a collection of recorded music.

La Sastrería Juarez, San Bernardino, California

Here’s an outlet I had never seen before – records sold at a tailor shop. Located in Southern California’s Inland Empire, the clothier’s sticker urged customers to “buy your phonographs and records” at Juarez Tailors. The tag line, however, takes the advertising pitch a step too far, promising that “today we have many new (musical) pieces,” though the word “piezas” in Spanish is misspelled. My question: How can you be sure the new stock will still be there on the day (“hoy”) the customer comes to the shop? The city of San Bernardino was also one of the earliest hubs of immigration for Mexican laborers, who worked on the railroads and the nearby Portland Cement Company. Once again, the recording is by the beloved Los Madrugadores, on the Brunswick label. Brunswick and other major labels of the era used specially numbered series to sell “race records,” referring to Black music such as jazz, blues, and gospel. The record companies also catered to Jewish, Russian, Italian, and other ethnic audiences.

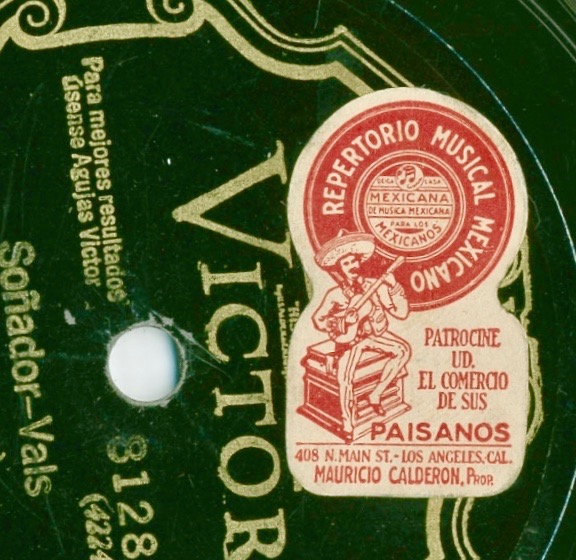

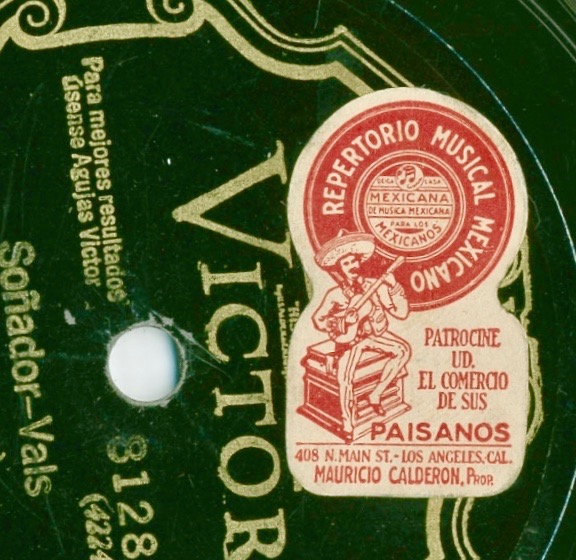

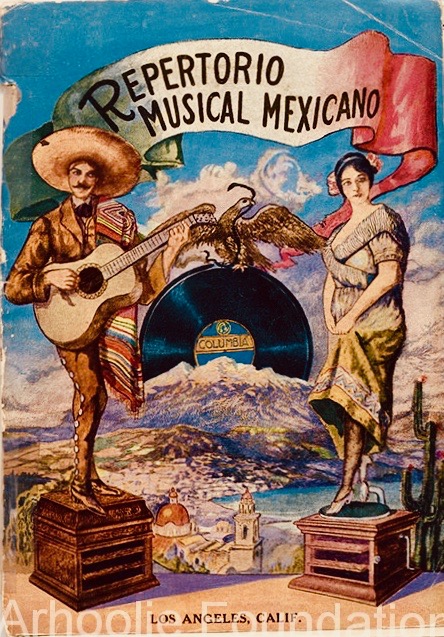

Repertorio Musical Mexicano, Los Angeles, California

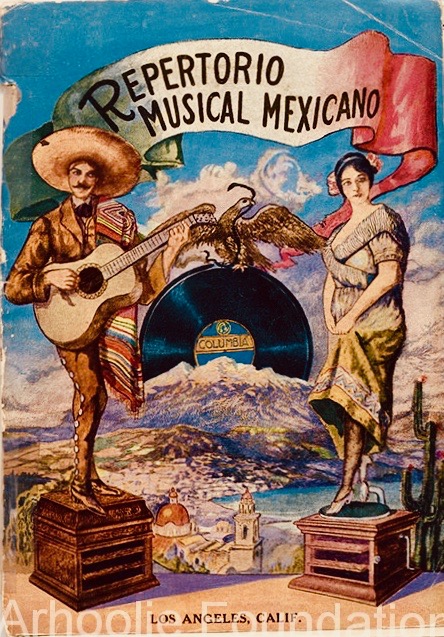

One of my favorite record store stickers belongs to a dealer located in downtown Los Angeles, which evokes personal memories that hit close to home. I love it for its unusual contoured shape, its graphic design, and its dual message addressing both commercial and community themes. The upper part is a section in the shape of a disc, with the store name in bold capital letters. At the center of the disc is a long slogan in small type that reads like a patriotic rallying cry: “From the Mexican house of Mexican music for all Mexicans.”

In the center, there’s an image of a slender charro playing a guitar next to a pithy sub-slogan that reinforces the mission statement: “Patronize the businesses of your Paisanos.” At the bottom, like a signature, is the owner’s name: Mauricio Calderon, proprietor.

Unlike Valle from Chicago, Calderon and his store are mentioned several times in historical studies of L.A.’s Mexican-American community. He was a prominent figure, both as a businessman and civic leader, during the 1920s when the Latino population surged in Southern California. His thriving retail store was considered “the center of the Latino music trade in the city,” according to a 2015 study, Latinos in Twentieth Century California, published by the California Office of Historic Preservation.

The store was located at 408 N. Main Street, close to Olvera Street in L.A.’s historic center. That site, on the block that includes the landmark Pico House, was a thriving hub of small businesses catering to the immigrant community, including La Ciudad de Mexico, a department store, and Farmacia Hidalgo, which sold traditional Mexican remedies along with Mexican sodas and ice cream, according to the study.

Repertorio Musical was so vital to the fledgling record business that it published its own 130-page catalog featuring “all available Mexican records on all major labels, (listed) by label and alphabetically by song title,” according to Philip Sonnichsen’s liner notes for the Arhoolie compilation CD, Corridos & Tragedias de la Frontera, produced by Chris Strachwitz. (The illustrated catalog also included song lyrics, instruments, and guitar chord diagrams.) Calderon’s shop, a magnet for musicians, has the distinction of being the place where Los Madrugadores was actually founded. The band was born when Los Hermanos Sanchez, a duo looking for career opportunities, visited the store one day and met Pedro J. González, who became the group’s celebrated director, according to Sonnichsen’s research for a compilation of the band’s material, part of Arhoolie’s “Historic Mexican American Music” series.

Repertorio Musical was so vital to the fledgling record business that it published its own 130-page catalog featuring “all available Mexican records on all major labels, (listed) by label and alphabetically by song title,” according to Philip Sonnichsen’s liner notes for the Arhoolie compilation CD, Corridos & Tragedias de la Frontera, produced by Chris Strachwitz. (The illustrated catalog also included song lyrics, instruments, and guitar chord diagrams.) Calderon’s shop, a magnet for musicians, has the distinction of being the place where Los Madrugadores was actually founded. The band was born when Los Hermanos Sanchez, a duo looking for career opportunities, visited the store one day and met Pedro J. González, who became the group’s celebrated director, according to Sonnichsen’s research for a compilation of the band’s material, part of Arhoolie’s “Historic Mexican American Music” series.

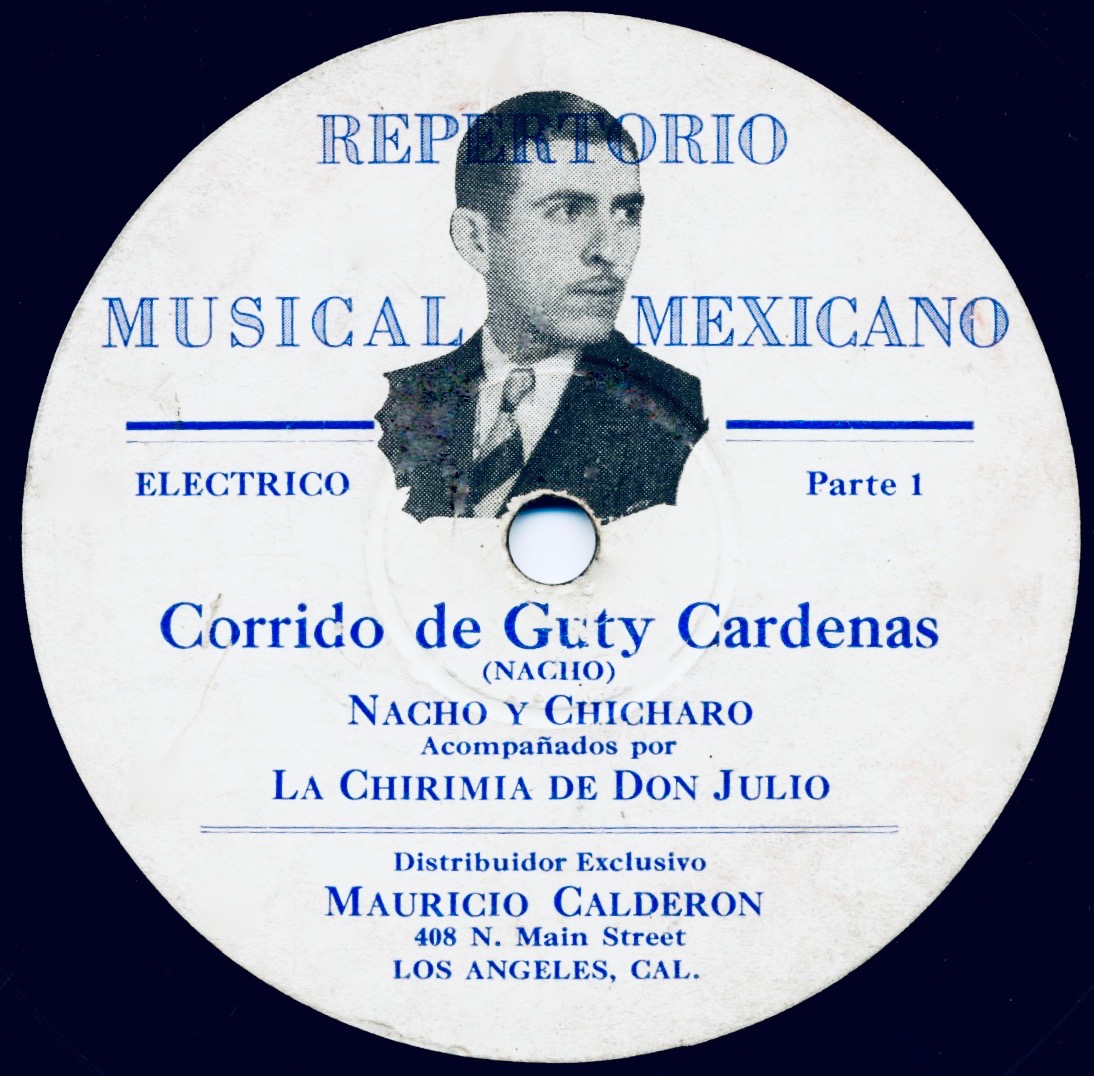

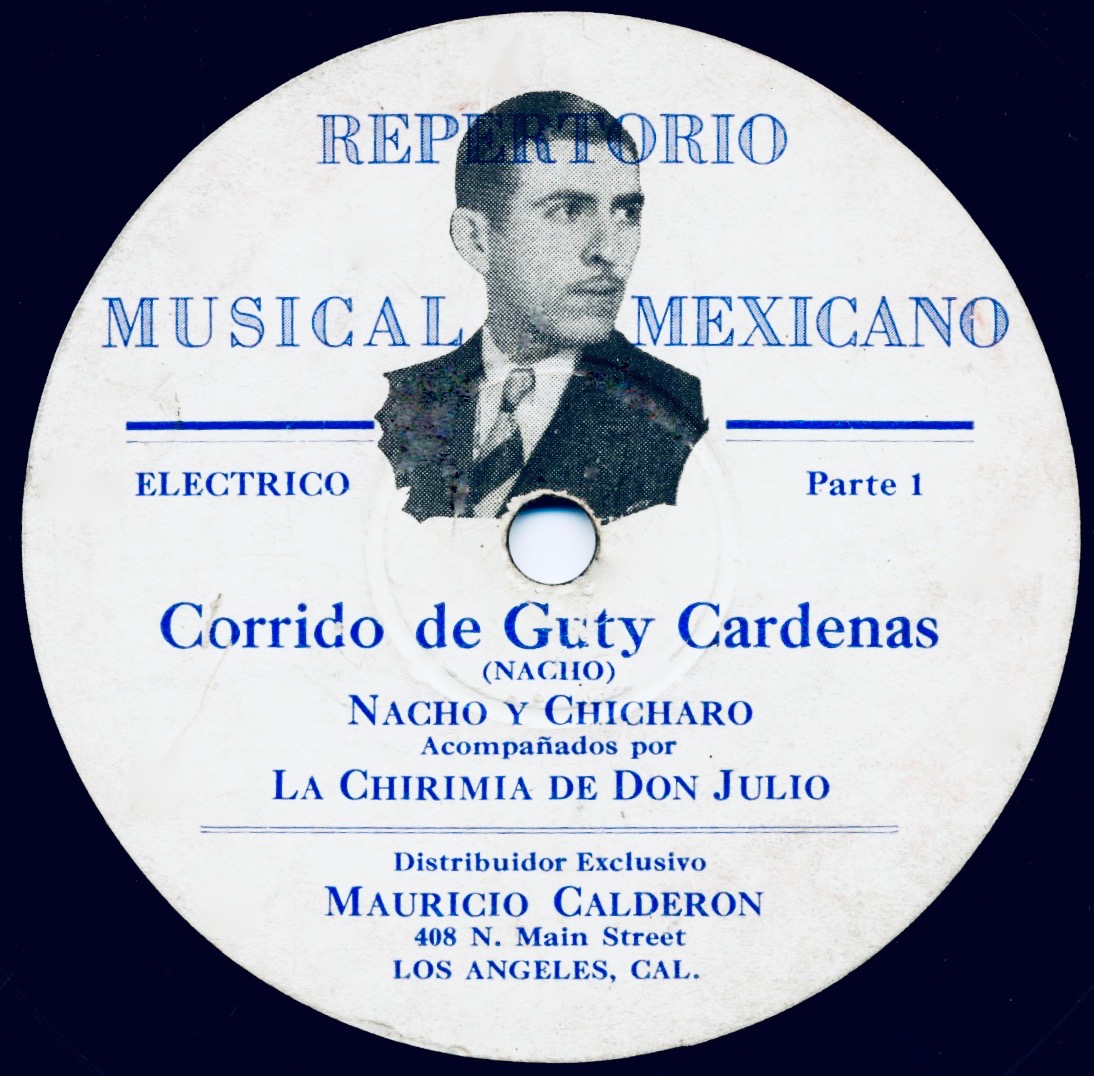

At one point, Calderon’s record shop totally bypassed the need for a store sticker by producing its own label. With a stark, black-and-white design, Repertorio Musical Mexicano released a two-part song titled “Corrido de Guty Cardenas” by Nacho y Chicharo. At the bottom of the label, the pioneering proprietor gave himself a credit line above his address: “Distribuidor Exclusivo: MAURICO CALDERON.”

There’s an old photo of Calderon’s store on Main Street, which evokes a bygone era. For me, it brought back memories of when I first moved to Los Angeles in the mid ‘70s and ventured out to explore downtown. One of my first stops was Doran’s Music on Broadway, where I met a clerk named Bill Marin who turned out to be a lifelong friend until his recent death. We shared a love of salsa and stood on the street after the store closed talking about our favorite by New York bands, whose records were hard to find in California at the time. Bill went on to be a West Coast rep for the major salsa label Fania Records, pitching me new releases in my new job as Latin Music Editor at Billboard Magazine.

There’s an old photo of Calderon’s store on Main Street, which evokes a bygone era. For me, it brought back memories of when I first moved to Los Angeles in the mid ‘70s and ventured out to explore downtown. One of my first stops was Doran’s Music on Broadway, where I met a clerk named Bill Marin who turned out to be a lifelong friend until his recent death. We shared a love of salsa and stood on the street after the store closed talking about our favorite by New York bands, whose records were hard to find in California at the time. Bill went on to be a West Coast rep for the major salsa label Fania Records, pitching me new releases in my new job as Latin Music Editor at Billboard Magazine.

In those days, Doran’s had two record store locations on Broadway, a few blocks apart. It shared the strip with several other record dealers that made downtown a record-buyer’s mecca. Aside from mom-and-pop stores, Latin music was also sold by Broadway’s ubiquitous electronic shops, which put records and tapes in bins at the entrance to lure pedestrians, which were almost entirely Latino in those days. Discount stores like Woolworth’s also featured well-stocked record departments. As a reporter for the trade magazine in the late ‘70s, I covered the splashy opening of a large record store owned by a Mexican company looking to establish a Tower-like chain in the U.S.

Those days are gone, of course. Not only did downtown demographics change, but the digital era killed off record retailers in all genres. It’s a deep loss for Mexican Americans, for whom these stores were more than just commercial outlets. They were also cultural centers where people came together to preserve traditional styles and make new music.

Those days are gone, of course. Not only did downtown demographics change, but the digital era killed off record retailers in all genres. It’s a deep loss for Mexican Americans, for whom these stores were more than just commercial outlets. They were also cultural centers where people came together to preserve traditional styles and make new music.

For immigrants far from home, the stores served as nodes of nostalgia.

“More often than not,” writes Cuellar, “these specialized shops were their only connection to life back home. They shopped there not only to see what new product they could find, but also to remember the life they had left behind.”

– Agustín Gurza

Tags

Images