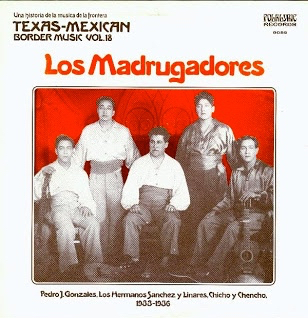

Artist Biography: Los Madrugadores de Pedro J. González

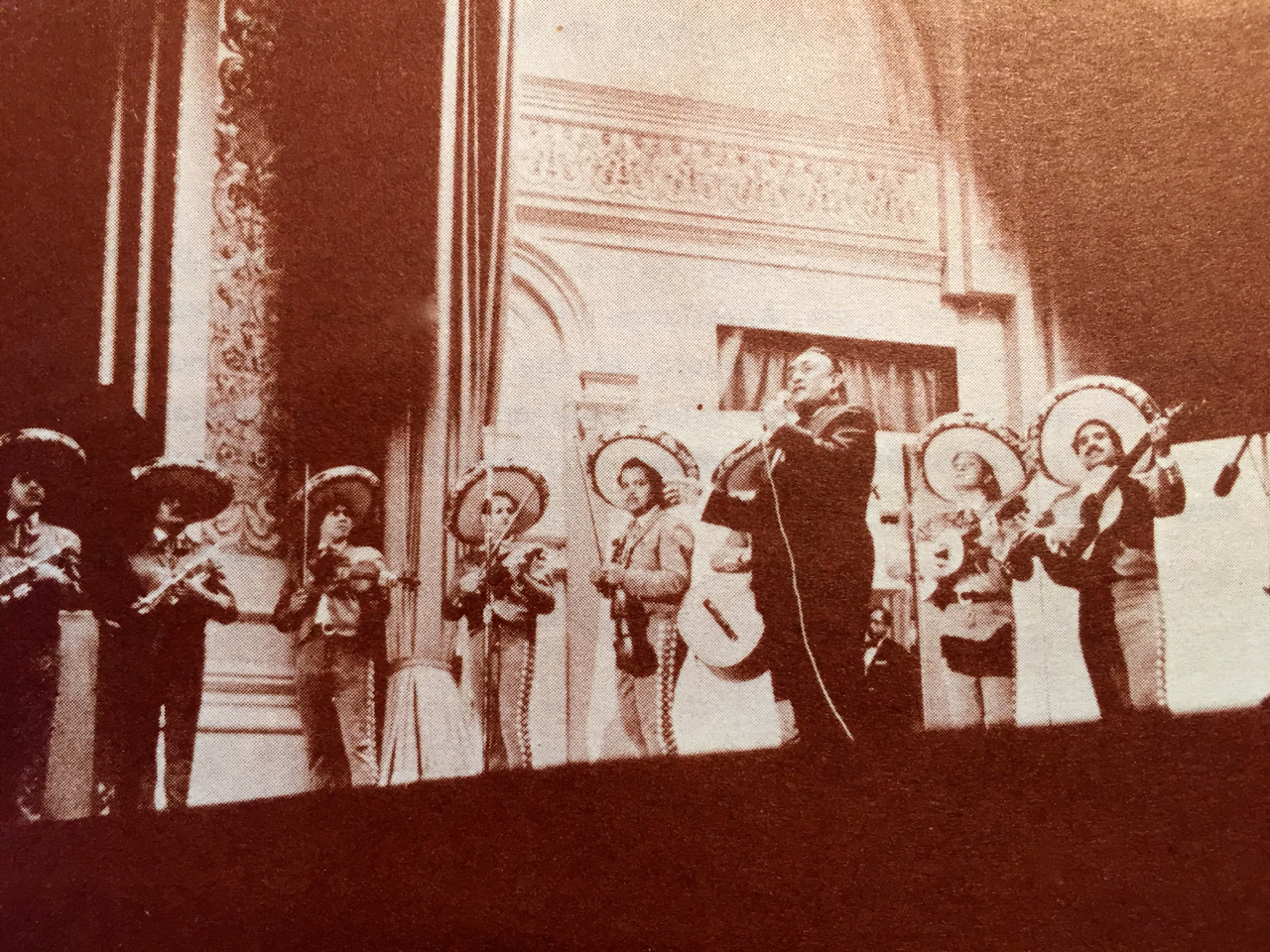

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, Los Madrugadores (The Early Risers) became the most popular group in Mexican-American music in the U.S. The folk ensemble was started by Pedro J. González, a controversial and charismatic personality considered the founder of Spanish-language radio in Los Angeles in the late 1920s. Its name – which comes from “madrugada,” the Spanish word for dawn – refers as much to the band as to its blue-collar audience, those “early risers” who listened to them perform live on the radio from 4 to 6 a.m. as they got ready to go to work. For a group that was marginalized, disdained, and persecuted during the Depression, the moniker also conveyed a certain sense of pride because it carried the connotation of being “hard workers” and “go-getters.”

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, Los Madrugadores (The Early Risers) became the most popular group in Mexican-American music in the U.S. The folk ensemble was started by Pedro J. González, a controversial and charismatic personality considered the founder of Spanish-language radio in Los Angeles in the late 1920s. Its name – which comes from “madrugada,” the Spanish word for dawn – refers as much to the band as to its blue-collar audience, those “early risers” who listened to them perform live on the radio from 4 to 6 a.m. as they got ready to go to work. For a group that was marginalized, disdained, and persecuted during the Depression, the moniker also conveyed a certain sense of pride because it carried the connotation of being “hard workers” and “go-getters.”

González, a musician and songwriter who was also a social activist and commentator, became even more closely identified with his immigrant audience when he was denounced for speaking out against the mass deportations of the day. The radio personality was framed on trumped-up rape charges, sent to prison, then later was himself deported to Mexico where he quickly returned to radio, broadcasting from Tijuana.

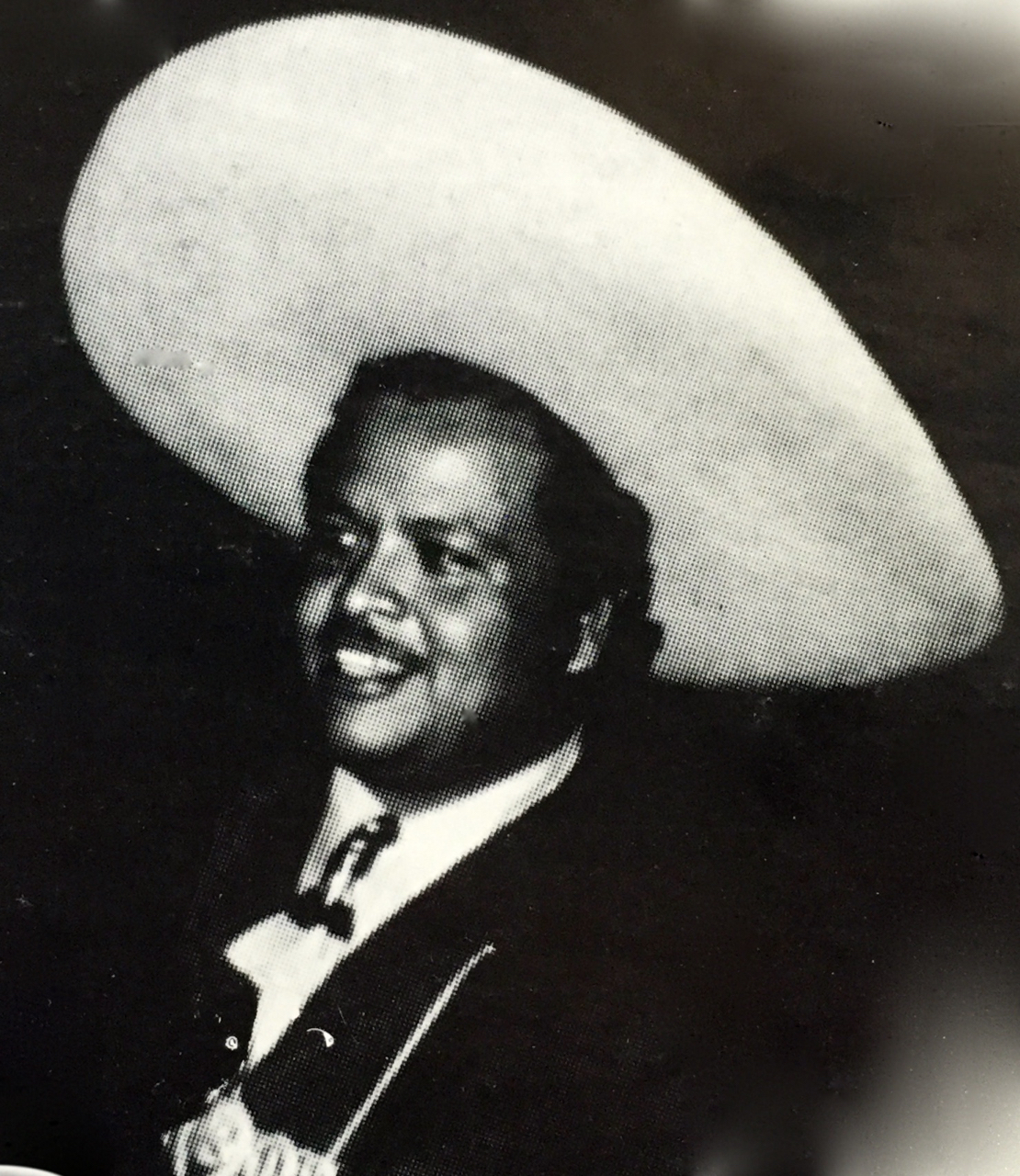

González was born in the northern border state of Chihuahua in 1896. He was 14 years old at the outbreak of the Mexican Revolution of 1910, when he was forced at gunpoint to join the rebel forces of Pancho Villa and conscripted as a telegraph operator. In 1923, according to The New York Times, he came to Los Angeles and found work as a longshoreman.

“His habit of singing while he worked led to his own Spanish-language radio show, one of the first in the nation,” states the Times story. “His broadcasts, during which he raged against mass deportations of Mexicans, were popular with Mexican field laborers but feared by the authorities, who accused him of being a rabble-rouser and tried to have his broadcasting license canceled.”

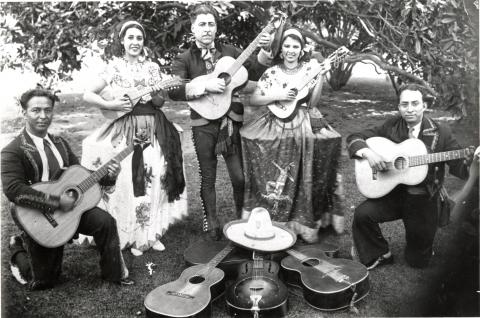

The history of Los Madrugadores dates to these radio broadcasts from the early 1920s in Los Angeles, for which González began organizing musical groups. From the start, the ensemble featured a revolving door of singers and musicians. Although González enjoyed performing, his radio audience soon preferred his accompanying singers and musicians, especially the popular band of brothers Jesus and Victor Sanchez, who also recorded separately under their own names. Singer Fernando Linares joined the group in the early days, creating another moniker for the ensemble as Los Hermanos Sanchez y Linares. The personnel expanded to include other singers and guitarists, such as Narciso Farfán, Crescencio Cuevas, Ismael Hernandez, Jesús Alvarez and Josefina “La Chata” Caldera.

Los Madrugadores became so popular that several groups used the same name, apparently by mutual agreement, to record and perform on stage and on the radio. They included Farfán and Cuevas, who became known as Chicho y Chencho, the most popular act spun off from Los Madrugadores. Collectively and individually, their popularity eventually spread throughout Mexican-American communities in California and the Southwest, where the daily radio broadcasts served as alarm clocks for workers in farms and factories. Groups by the same name continued to work all along the border up into the 1970s.

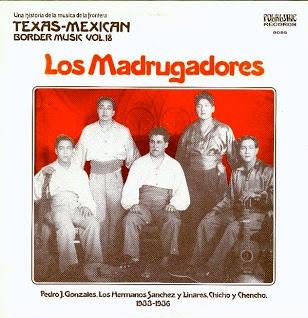

The Frontera Collection contains scores of recordings by Los Madrugadores, including many found under the name of Pedro J. González, who was also a songwriter. (Not to be confused with Los Madrugadores del Valle, a more recent norteño group that recorded many singles and LPs for the Joey and Del Valle labels of Texas.)

Frontera founder Chris Strachwitz cited the group’s version of the classic “Zenaida” (Vocalion 8596) as one of his 50 favorite recordings from the collection, ranking it No. 15.

“I can’t get this wonderful melody out of my head—I try to sing or hum it constantly,” writes Strachwitz on this blog. “Los Madrugadores were the first to record this story about Zenaida, and they did it in two parts. Great singers, they were very popular in the mid-1930s and the song soon gained widespread popularity as well.”

In various configurations, Los Madrugadores issued numerous singles in the 1930s that enjoyed strong record sales and jukebox play. Their canciones and corridos emphasized close harmonies and accomplished guitars as accompaniment, although some of the early discs also have piano. The group recorded over 200 songs for both multi-national and independent labels, including RCA Victor, Columbia, Decca, Vocalion, Bluebird, Imperial, and Tricolor.

All the while, González continued to use the airwaves to agitate for social justice, soon drawing the attention and ire of the authorities. In 1934, at the peak of his career, González was sent to San Quentin prison on rape charges. Although the alleged victim later recanted, saying she had been coerced by prosecutors to lie under oath, the conviction was allowed to stand and González served six years.

All the while, González continued to use the airwaves to agitate for social justice, soon drawing the attention and ire of the authorities. In 1934, at the peak of his career, González was sent to San Quentin prison on rape charges. Although the alleged victim later recanted, saying she had been coerced by prosecutors to lie under oath, the conviction was allowed to stand and González served six years.

The musician/activist was released in the early 1940s after appeals by two Mexican presidents and huge public protests organized principally by his wife, Maria. He was deported to Mexico and settled in Tijuana, where he immediately reassembled a band and took again to the airwaves. Undaunted, González continued to use his radio show to speak out against injustice, blasting broadcasts across the border for the next 30 years.

Los Madrugadores documented the tragic case of their leader in a two-part ballad, the “Corrido de Pedro J. González.” It was a case of life imitating art, since around the same time the group had also recorded the corrido of another Mexican-American folk hero, Joaquin Murrieta, a 19th century outlaw whose severed head was paraded on display in mining towns throughout the state. As American studies professor Shelley Streeby noted, “...the story of the unjust treatment and criminalization of a Mexican immigrant (Murrieta) in the United States must have taken on new and tragic resonances for that working-class audience during these years of intensified nativism and forced repatriation, especially in light of González’ harsh experiences with the law.”

Both two-part corridos – Joaquín Murrieta and Pedro J. González – are part of the Frontera Collection and included in the compilation CD, “Los Madrugadores - 1931-1937.” (Arhoolie 7035).

Meanwhile, back in Los Angeles, other events forced changes in the lineup of the original Madrugadores, especially the deaths of Narciso Farfan in 1939 and Jesus Sanchez in 1941. Despite the setbacks and challenges, the group stayed true to the determined spirit of its immigrant audience, continuing to record and perform until the 1960s.

Eventually, González was permitted to return to the United States. In 1985, when he was 90, PBS aired a documentary on his life and career titled Ballad of an Unsung Hero, which was later turned into a TV movie, Break of Dawn (1988), starring Mexican folk singer Oscar Chavez. González and his wife are both featured in the 30-minute documentary, interviewed at their modest home in the border town of San Ysidro, California. González devoted one room of the home to a museum of his life, featuring old photographs, newspaper clippings, letters, and even an old telegraph key.

Eventually, González was permitted to return to the United States. In 1985, when he was 90, PBS aired a documentary on his life and career titled Ballad of an Unsung Hero, which was later turned into a TV movie, Break of Dawn (1988), starring Mexican folk singer Oscar Chavez. González and his wife are both featured in the 30-minute documentary, interviewed at their modest home in the border town of San Ysidro, California. González devoted one room of the home to a museum of his life, featuring old photographs, newspaper clippings, letters, and even an old telegraph key.

The show sparked a renewed interest in the aging activist among Mexican- American community activists, who started visiting the home like a shrine, according to a New York Times article about the documentary, published January 7, 1985.

“He represents an important part of cultural past and tradition,” Lorena Parlee, a historian and co-producer of the program, told the newspaper. “And the film represents not only the plight of immigrants from Mexico but from other ethnic groups who experienced discrimination and deportation.”

Ten years later, González passed away at a convalescent home in Lodi, California. The headline of , which ran in The New York Times on March 24, 1995, called him, appropriately, a “folk hero.” He was 99.

-Agustín Gurza

Blog Category

Tags

Images