The Triumphant Return of Los Camperos

When I was in college, my father would make occasional trips from San Jose to Los Angeles to see the new mariachi at La Fonda, a restaurant on Wilshire Boulevard His visits were more like musical pilgrimages. Dr. Gurza would say there was no place to hear a good mariachi in the Bay Area. So, whenever he’d drive south, ostensibly to visit a friend from our hometown of Torreon, he’d always make a beeline for La Fonda first. That was an 8-hour drive in those days, on the old 101 Highway. But Dad was never too tired to take in a set or two by Los Camperos de Nati Cano.

When I was in college, my father would make occasional trips from San Jose to Los Angeles to see the new mariachi at La Fonda, a restaurant on Wilshire Boulevard His visits were more like musical pilgrimages. Dr. Gurza would say there was no place to hear a good mariachi in the Bay Area. So, whenever he’d drive south, ostensibly to visit a friend from our hometown of Torreon, he’d always make a beeline for La Fonda first. That was an 8-hour drive in those days, on the old 101 Highway. But Dad was never too tired to take in a set or two by Los Camperos de Nati Cano.

Fast forward almost 40 years. I’m standing in La Fonda again, this time as a writer for the Los Angeles Times, interviewing Nati Cano as he was about to be evicted from his longtime location. He was in the midst of legal dispute with his landlord over rent increases, a victim of the gentrification that has pushed so many Latinos out of homes and businesses in barrios throughout California. It would be a losing battle for the veteran musician who had done so much to elevate the status of mariachi music north of the border. Ultimately, in 2007 he was forced to abandon the location he had occupied for almost half a century. Seven years later, he passed away.

I always carried a touch of cultural resentment over that episode in the history of Mexican-American music in Los Angeles. All things must pass, as George Harrison said. But this transition left a bad taste. Cano, who devoted his career to promoting mariachi music in Southern California, was unceremoniously removed from the venue he had established in 1969, when there was nothing like it in our area. Cano is considered the first to create a showcase for a local mariachi by putting his ensemble on a raised stage, thus making it a focal point of his restaurant. This was at a time when the average mariachi was more commonly a strolling band of minstrels playing for tips. So, the formal, dinner-theater format was received by fans as an exciting and validating innovation.

And then Nati Cano and his Camperos were pushed aside, not for progress, but for profit.

This sad story would make a tragic corrido, if it weren’t for the surprise happy ending. This year, Los Camperos have returned to

their original, revered venue, resuming regular dinner shows as the house band at La Fonda. In its new incarnation, Mariachi Los Camperos is under the direction of Jesus “Chuy” Guzman, a veteran of the ensemble who worked with Cano and who is also a lecturer in Mexican music in UCLA’s Department of Ethnomusicology.

The restaurant has been somewhat remodeled, with a smaller stage tucked into a corner and a more open floor plan making the performance visible from the bar. Old paintings of the ensemble’s past players have been taken down, except for one. The only portrait left hanging, fittingly, is a flattering image of the restaurant’s smiling founder, Nati Cano.

The show at La Fonda continues to attract an international audience, including many tourists. At the same time, Los Camperos have kept up their busy touring schedule, carrying the standard of concert-quality mariachi music around the world.

“I can only attest to the love people have for them anywhere they've spread their magic,” says NPR music journalist Felix Contreras, who recalls seeing Cano and his Camperos at a mariachi festival in Fresno years ago. “Fresno audiences welcomed them not just for the reputation that the group had earned, but mostly because of the group's ability to play mariachi from the heart that spoke directly to the people.”

“I can only attest to the love people have for them anywhere they've spread their magic,” says NPR music journalist Felix Contreras, who recalls seeing Cano and his Camperos at a mariachi festival in Fresno years ago. “Fresno audiences welcomed them not just for the reputation that the group had earned, but mostly because of the group's ability to play mariachi from the heart that spoke directly to the people.”

The Frontera Collection includes several recordings by Los Camperos, both LPs and 45-rpm singles on various labels. A search yields results for the group under different names: Mariachi Los Camperos, Super Mariachi Los Camperos, and Mariachi Los Camperos de Nati Cano.

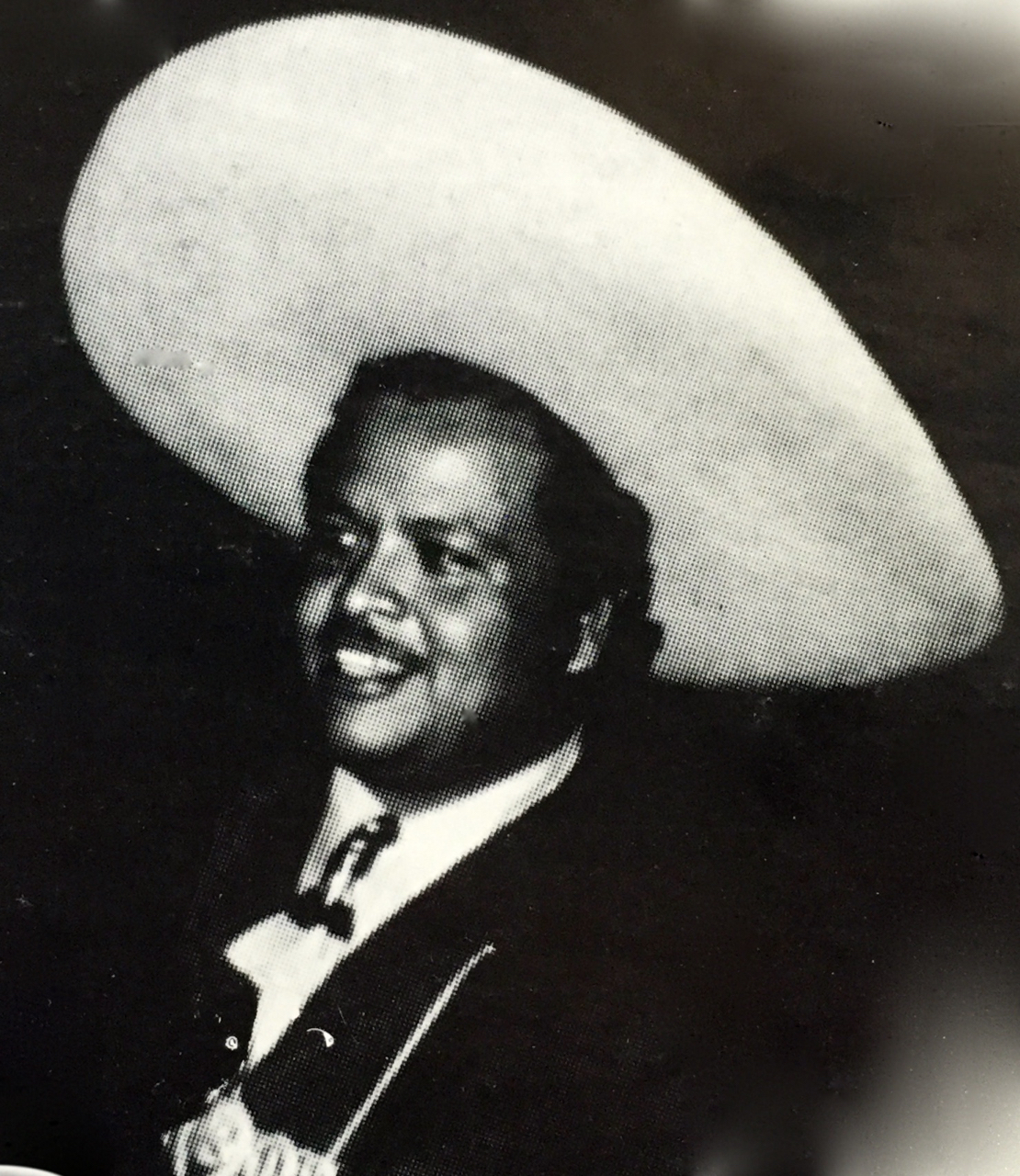

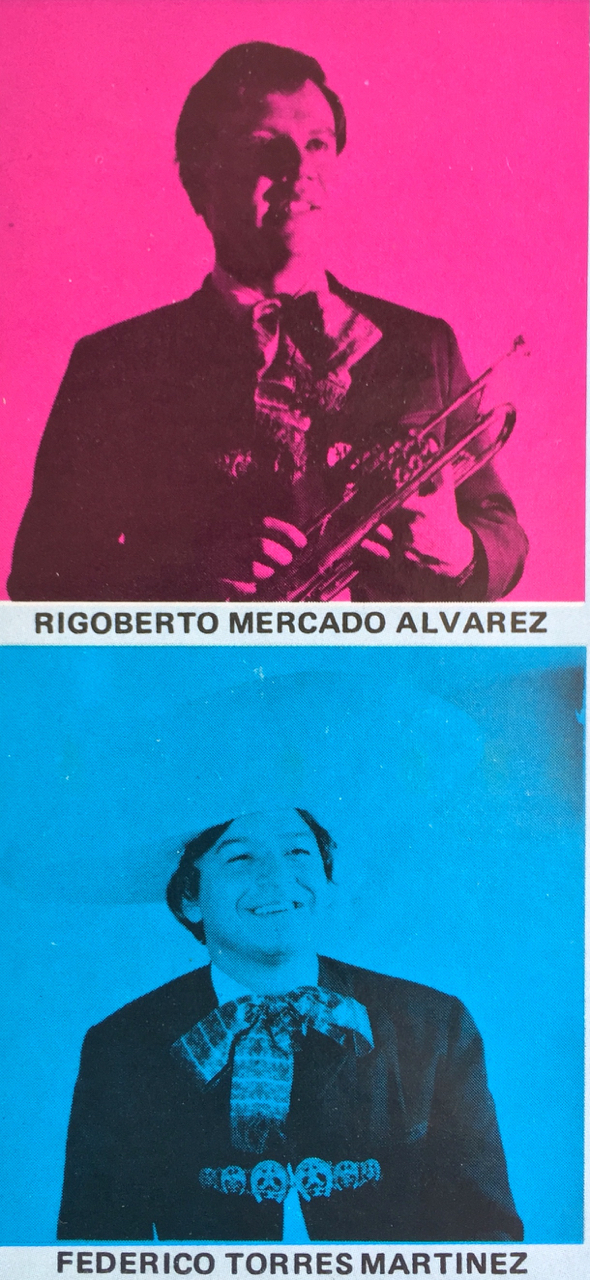

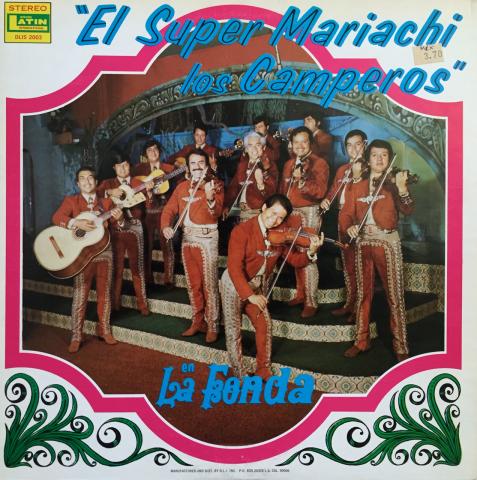

One of those singles features “Somos Novios,” the Armando Manzanero classic, backed by “Yo Sin Ti.” The songs are from an LP that is not in the database and entitled “El Super Mariachi Los Camperos en La Fonda.” The album is not dated, but my personal copy has autographs by some band members with a date under one of the signatures: August 5, 1972. That is only three years after Cano opened La Fonda, and the group picture on the cover shows the bandleader as a young man, holding his violin and smiling, of course.

The recording was released on Latin International, a local label owned by Pepe Garcia, another pioneering figure in the local Latin music industry. Garcia, a Cuban-American who had moved to L.A. from Miami, had built a mini-music empire, which he lorded over with regal authority. His businesses included the record label and a wholesale record distributor, all based at his flagship retail music store called Musica Latina, located on Pico Boulevard and only a 10-minute drive from La Fonda. The imposing corner building was a landmark of L.A.’s burgeoning record industry, with labels from Mexico opening branch offices for U.S. sales all along the Pico corridor just west of downtown. At the time, the Latin business was still largely ghettoized, concentrated in areas like “La Pico” and along Broadway, then an all-Latino shopping district, dotted with Latin record stores in a pre-gentrified downtown. Latino music mavens would gather for lunch at a Cuban restaurant called El Colmao, adjacent to Musica Latina. The restaurant is still there, although Musica Latina is long gone, along with the rest of the area’s once thriving Latin record business.

I mention that background by way of context for the importance of this early Camperos LP. It captures this seminal period in L.A.’s Latin music industry, when local artists and businessmen came together to make their mark. Some, like Cano, would succeed beyond their dreams.

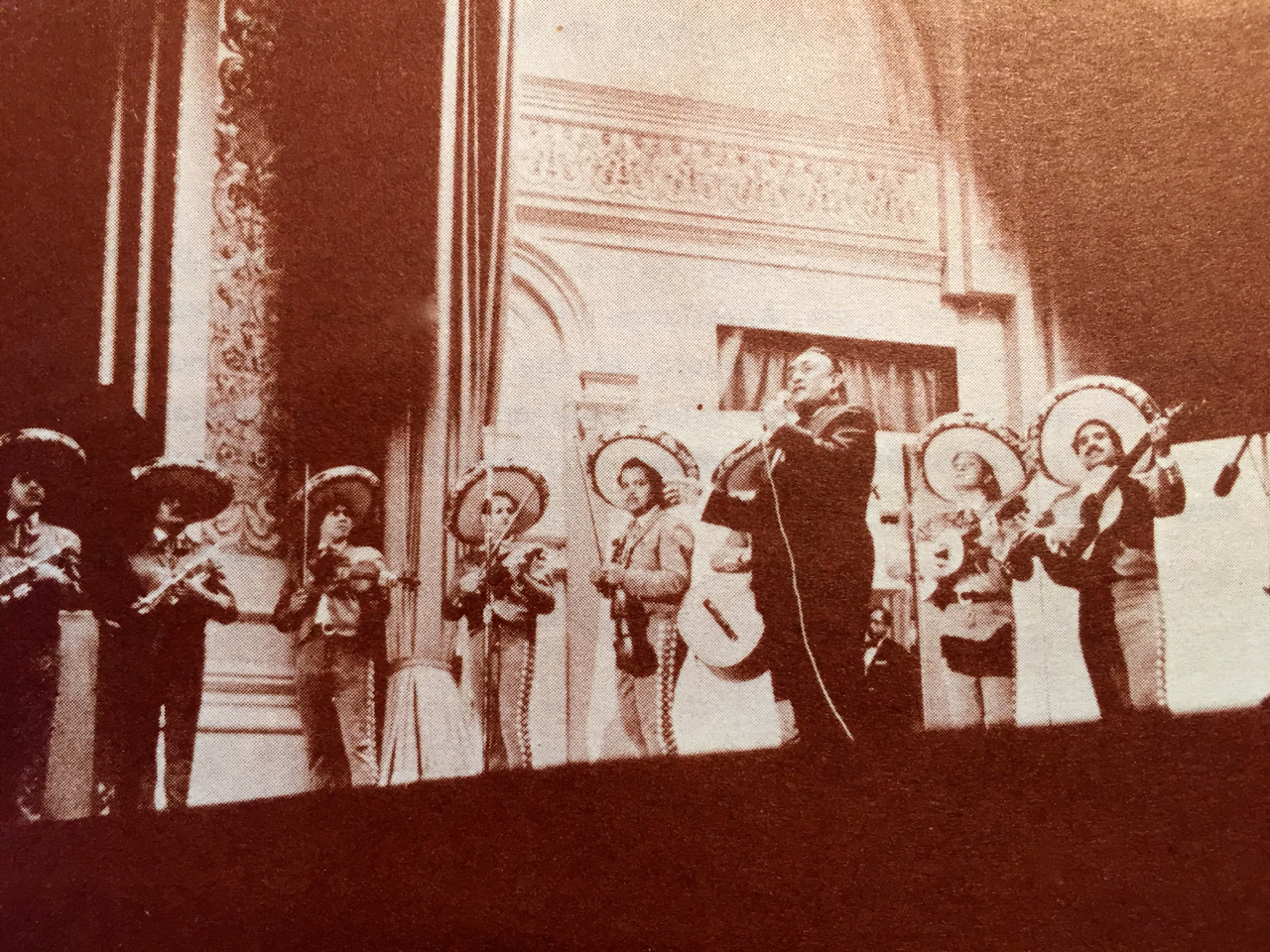

Los Camperos first gained an international spotlight in 1964 when they performed at Carnegie Hall as accompaniment for Pedro Vargas, one of the most popular Mexican singing stars of the day. The concert was recorded live and released as a box set by RCA Victor. My copy of the album includes a program booklet with a small photo of Los Camperos on stage with Vargas at the famed New York venue. In a somewhat condescending review of the show, The New York Times called the concert “sentimental,” compared the singer’s popularity to a “serape,” and noted that Vargas exchanged a “brazo” during the show with the Mexican ambassador, evoking a gruesome image of the men swapping arms on stage rather than an embrace (“abrazo”). The review reflects the demeaning, stereotypical attitudes towards the music that Cano fought hard to counteract during his career.

Los Camperos first gained an international spotlight in 1964 when they performed at Carnegie Hall as accompaniment for Pedro Vargas, one of the most popular Mexican singing stars of the day. The concert was recorded live and released as a box set by RCA Victor. My copy of the album includes a program booklet with a small photo of Los Camperos on stage with Vargas at the famed New York venue. In a somewhat condescending review of the show, The New York Times called the concert “sentimental,” compared the singer’s popularity to a “serape,” and noted that Vargas exchanged a “brazo” during the show with the Mexican ambassador, evoking a gruesome image of the men swapping arms on stage rather than an embrace (“abrazo”). The review reflects the demeaning, stereotypical attitudes towards the music that Cano fought hard to counteract during his career.

Almost a quarter century later, Cano and his Camperos participated in another landmark collaboration, this time with singer Linda Ronstadt for her recording of Mexican mariachi standards, Canciones de Mi Padre. (The full album is included in the Frontera Collection, though neither Nati Cano nor Los Camperos are credited as one of her backup mariachis.) Ronstadt recalls rehearsing with Los Camperos in a rear storage room at La Fonda. In an interview for my 2001 profile of Cano in the Los Angeles Times, Ronstadt told me she considered the mariachi bandleader a mentor who helped her capture the authentic feel of the genre.

That album, and a sequel, Mas Canciones, that also featured Los Camperos, sparked a revival of interest in mariachi music throughout the United States. Cano pointed to those albums as a milestone in the campaign to bring greater respect for mariachi music as a genre.

Cano’s dinner-theater concept has since been imitated by other mariachis across Southern California and the Southwest. Today, it’s almost taken for granted. But it’s hard to overstate how exciting the show was when it was first introduced. Consider the following account by Daniel Sheehy, director of the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, who earned his doctorate in ethnomusicology at UCLA in 1979. Sheehy, who joined a campus mariachi ensemble as a student, recalls the thrill of his first visit to La Fonda in 1969.

“For my fellow student mariachi enthusiasts and me, a trip to La Fonda was akin to visiting a sacred temple of mariachi music, and Nati Cano was its high priest,” Sheehy writes in the liner notes for the 2002 Camperos CD ¡Viva El Mariachi! on Smithsonian Folkways, the label he directed at the time. “His life’s goal has been to bring greater acceptance, understanding, and respect to the mariachi tradition, and to reach the widest possible audience with his music. His uncompromising position has been to preserve the essential ‘mariachi sound,’ in his words, as the baseline of the tradition. I know that many would agree that in this, he has succeeded.”

–Agustín Gurza

Tags

Images