the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center,

the Arhoolie Foundation,

and the UCLA Digital Library

Part of the frustration of building a musical archive like the Frontera Collection is the lack of reliable and readily available information for every recording. Key data – such as release dates, accompaniment, musician credits, and studio locations – is often missing or simply beyond the reach of researchers.

Part of the frustration of building a musical archive like the Frontera Collection is the lack of reliable and readily available information for every recording. Key data – such as release dates, accompaniment, musician credits, and studio locations – is often missing or simply beyond the reach of researchers.

I always thought that this problem was particularly pronounced in the Latin music industry. By comparison, I’d often see deep, detailed information for popular English-language genres, such as jazz, pop, rock, and folk. For groups like The Beatles, with fervent followers, there are more minutiae about their recordings than the average fan could ever need, let alone process.

Despite the incomplete data – or perhaps because of it – Frontera’s digital library is an invaluable global resource. It’s a one-of-a-kind repository of recordings, some of which are the last surviving copies that otherwise would have been long ago lost and forgotten. And it represents decades of devoted research and acquisition by a driven record collector, Chris Strachwitz, founder of the Arhoolie Foundation.

Passionate collectors like Strachwitz are the driving force in the field known as discography, the systematic cataloguing of commercial recordings. Not the record labels, not research institutions, not even the artists themselves have played such a pivotal role in a field that emerged in the early 1930s as a labor of love.

“Discography has always been the work of amateurs,” writes Bruce D. Epperson in his book, More Important Than the Music: A History of Jazz Discography (University of Chicago Press, 2013). “Nobody ever went to discography school, or got a degree in it, or joined a discographers’ union. There is no defined body of special skills handed down from one generation to the next. It’s always been something that each individual has had to learn on the job.”

With that pioneer spirit, Strachwitz set about, almost a quarter century ago, to create the first comprehensive discography of Discos Peerless, the original national record company in Mexico. He teamed with two collaborators for the daunting undertaking: Jonathan Clark, a mariachi musician and historian, and the late James Nicolopulos, former professor at of the University of Texas at Austin with a special interest in Mexican corridos.

“It was important because, at the time, there was no other discography in Mexico of Mexican music,” said Clark in an interview, “and it was logical to start with Peerless because it was Mexico’s oldest national record company.”

In the summer of 1995, the trio of discographers travelled to Mexico City to begin their groundbreaking work. They had no clear idea of the quality of the firm’s historical files. They didn’t know how complete and accurate they would be, nor how far back they might go.

As we shall see, the company’s recordkeeping was fragmented, with no central data or single source to help them compile of releases dating back to the early 1930s. The work would require a dogged search through dusty record shelves, forgotten file rooms, and rows of old card catalogues, similar to those used in libraries beginning in the 1800s.

“Nobody had ever made an attempt to consolidate all that information,” said Clark, “so there were a lot of different sources. And each different source of documentation contained unique information about each record that none of the other sources had.”

As it turns out, the patchwork nature of the label’s in-house data was not unusual for the record industry, especially in its formative years, according to Roy Shuker of Victoria University in New Zealand who has written several books on the culture of popular music and record collecting.

“The early recording companies were frequently very unsystematic in their cataloguing practices,” writes Shuker in his reference book, Popular Music: The Key Concepts (Routledge, 2017). “There was a general lack of catalogues of released recordings, especially from the smaller companies, along with a failure to keep thorough records of releases. This lack of systematic and accessible information on releases made record collecting a challenge, and fostered the growth of discography, especially among jazz enthusiasts and record collectors.”

Strachwitz emphatically disagrees with Shuker’s assessment. He says record companies kept excellent records, especially in the early years of the recording industry. It was not until the 1940s, Strachwitz states, that labels became less rigorous about their recordkeeping.

Disputes are part of the discographer’s DNA. Historically, observes Epperson, they have argued, sometimes ferociously, over everything from arcane recording data to what qualifies as a certain style of music. Their “internecine battles,” wrote the late Edward Berger, a renowned jazz expert, mirrored comparable conflicts among jazz writers and critics.

It was a Parisian jazz fanatique, in fact, who created one of the world’s first comprehensive discographies. French critic Charles Delaunay’s Hot Discography, published in 1936, is considered the first complete compilation of jazz recordings.

Some sources erroneously claim that Delaunay actually coined the term “discography.” That credit belongs instead to Compton Mackenzie, a Scottish author, actor, and activist who co-founded the London-based magazine, Gramophone. According to Epperson, the term first appeared in print in an editorial published by the magazine in January 1930.

“I have often thought that I should like to start a museum to house one specimen of every kind of disc record ever published,” wrote Mackenzie. “I wonder how many there would be? I wish some devoted reader would set himself the task of making out a list … Now, who will volunteer for this noble but arduous task?”

When Strachwitz and the team undertook that arduous task at Peerless, they took a big gamble on the company’s cooperation. They arrived with only a preliminary, unofficial agreement to start the research. Nicolopulos, who led the team, had previously worked with a mid-level manager, the head of the royalties department, for his research on corridos. But top management had not signed off on the company-wide discography project.

“From past experience, I was aware of the fact that many record companies, especially in Mexico, are suspicious of anyone trying to obtain discographical information,” writes Strachwitz in his introduction to the Peerless Discography on the Arhoolie Foundation website. “They generally consider this confidential data because they feel it might reveal sales figures and/or royalty payments to publishers and/or artists, or the lack thereof.”

Luckily, a personal connection helped break the ice.

Strachwitz, who doesn’t speak Spanish, shared his German ancestry with Jürgen Ulrich, then president of the company, who was born in Mexico but studied in Germany.

“Sprechen Sie Deutsch?” Jürgen asked in an initial meeting.

There followed what Strachwitz calls, in diplomatic terms, “a fruitful conversation.” Clark remembers it as the parting of the waters.

“They started speaking in German and that was an additional in, I think, that made him even more friendly,” Clark said. “So Ulrich was really cordial to us and he basically said, ‘Look, you guys can have the run of the plant.’ And he took us to each office … to the royalties office, to the tape library, to the record archives, and he introduced us to each person in charge and said, “Give these guys full access.”

The team also arrived with a powerful door opener: a copy of what is considered in the U.S. the Bible of discographies, Ethnic Music on Records: A Discography of Ethnic Recordings Produced in the United States, 1893-1942 (University of Illinois Press, 1990) by Richard K. Spottswood, a musicologist with a degree in library science. Specifically, they brought Volume 4 of Spottswood’s seven-part opus, focusing on “Spanish, Portuguese, Philippine, (and) Basque” releases.

Showing an example of Spottswood’s comprehensive catalogue, recalls Strachwitz, helped convince label executives of the value of the enterprise.

Even under these ideal circumstances, the team encountered the same obstacles faced by other discographers, though perhaps somewhat more daunting.

“Peerless published few, if any, listings or catalogues of their releases until the advent of LPs (long-play records) in the 1950s,” writes Strachwitz. “Collectors, researchers, scholars, and fans of Mexican music have long been frustrated by the lack of information available regarding early Peerless recordings. The only listings of releases I had ever seen were short lists of currently popular items printed on the sleeves of 78-rpm records.”

Upon arrival at the Peerless facilities, Strachwitz and his team discovered more disheartening news.

The company had no documentation for releases prior to 1939, the year the firm moved to its longtime headquarters on Avenida Mariano Escobedo, since demolished. That physical move coincides with the start of a new catalogue series, Peerless 1501, with a new matrix series, 1-39, the code number etched into the run-out groove of every Peerless record. Conveniently, the last two-digits represent the year of release, a date rarely specified on phonograph discs. In addition, company records indicated that many masters and matrices, the crucial metal parts of the production process, had been melted down for scrap metal.

The company had no documentation for releases prior to 1939, the year the firm moved to its longtime headquarters on Avenida Mariano Escobedo, since demolished. That physical move coincides with the start of a new catalogue series, Peerless 1501, with a new matrix series, 1-39, the code number etched into the run-out groove of every Peerless record. Conveniently, the last two-digits represent the year of release, a date rarely specified on phonograph discs. In addition, company records indicated that many masters and matrices, the crucial metal parts of the production process, had been melted down for scrap metal.

Even today, historical information about the company is scattered piecemeal across various sources, and is not entirely reliable. There are even conflicting dates for the year the firm was founded. Strachwitz cites the date of incorporation – Monday, August 14, 1933 – as noted in a special edition of the trade magazine DiscoMexico, published on the label’s 50th anniversary under the headline, “La Primera Compañía Fonográfica de México: 1933-1983.”

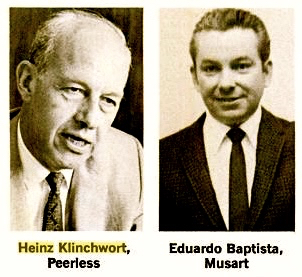

Fábrica de Discos Peerless, a source of cultural pride for Mexicans, was founded ironically by two entrepreneurial immigrants: German-born Gustavo Klinkwort Noehrenberg, Ulrich’s grandfather, and Eduardo C. Baptista Covarrubias, a native of Venezuela. Klinkwort had moved to Mexico in 1906 and Baptista in 1921, according to online sources.

By the time they became partners in Discos Peerless, the two men had already laid down the firm’s foundations, working independently on career tracks that would soon merge.

In 1925, Baptista established a short-lived record factory with machinery he imported from New York, including a mill to mix shellac for making 78s. The milestone is proudly noted in a timeline written by the executive himself, “The Record Industry in Mexico,” published in Billboard on February 28, 1970.

But Baptista fails to mention the fact, noted by Strachwitz and others, that the equipment was obsolete and the audio quality of the early recordings was sub-par. The sound was so bad, in fact, that the poor quality was cited as the reason the early masters were destroyed.

In 1927, Baptista formalized the enterprise, founding his Compañía Nacional de Discos. He operated a small fleet of labels – Olympia, Huici, Artex, and Nacional – that were discontinued by the time Peerless was established, according to a 2006 doctoral dissertation by Donald Andrew Henriques, Performing Nationalism: Mariachi, Media and the Transformation of a Tradition (1920-1942).

“Baptista had a recording studio in the Teatro Politeama and it was there that he recorded vocalists from radio, musical theater, and film,” writes Henriques, who earned his degree in ethnomusicology at the University of Texas at Austin, and now is Assistant Professor of Music at California State University, Fresno.

Far from glamorous, the theater, long since demolished, was a venue for vaudeville-style shows, located in what was then a sordid, low-rent district south of Mexico City’s historic center. Yet, it placed Baptista at the heart of the action, where aspiring future stars were hard at work making a name for themselves.

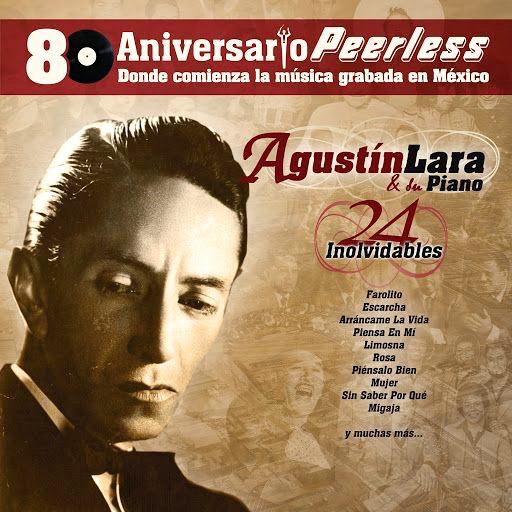

Despite the admittedly crude production quality, Baptista managed to make the first recordings of artists who would go on to become superstars in the Mexican music business. In his industry timeline, Baptista cites his early recordings by Pedro Vargas, Guty Cardenas, Agustín Lara, and Alfonso Ortiz Tirado.

Despite the admittedly crude production quality, Baptista managed to make the first recordings of artists who would go on to become superstars in the Mexican music business. In his industry timeline, Baptista cites his early recordings by Pedro Vargas, Guty Cardenas, Agustín Lara, and Alfonso Ortiz Tirado.

Meanwhile, Klinkwort was busy building his own roster of releases. In 1929, the first recordings appeared on the Peerless label, “probably under (Klinkwort’s) ownership,” Strachwitz notes. Those early Peerless recordings also included music by the iconic Agustín Lara and Guty Cardenas, who pioneered the romantic trova yucateca, as well as Tito Guízar, a singer and actor who scored early success in Hollywood.

At the time, Peerless and its predecessors had a clear field in the Mexican recording industry. After the Revolution of 1910, three major U.S. labels – Columbia, Victor, and Edison – found it too dangerous to continue doing business in Mexico. The multinationals would not establish full operations, with recording and manufacturing facilities, until the 1930s and ’40s.

That left Peerless for many years with an open market to establish its national brand.

“Obviously, any artist who wanted to record and become known had to pass through Peerless,” said Ulrich in a 2013 interview with Excelsior on the occasion of the label’s 80th anniversary. “Our business was not just to make money, but also to make public our musical culture. All the songs that we heard, and all the artists, those who shone and those who didn’t, are part of the Mexican identity, its idiosyncrasy.”

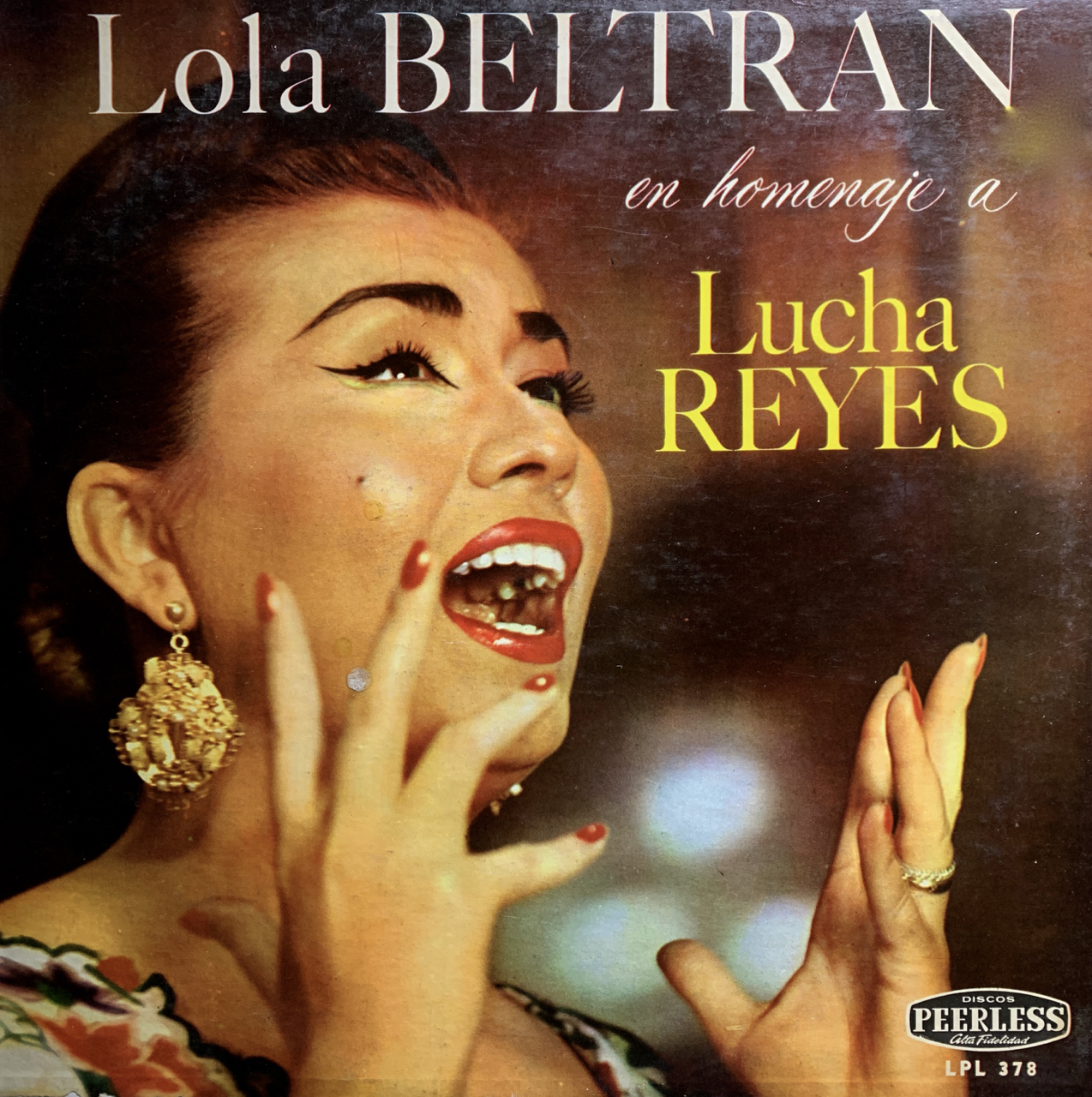

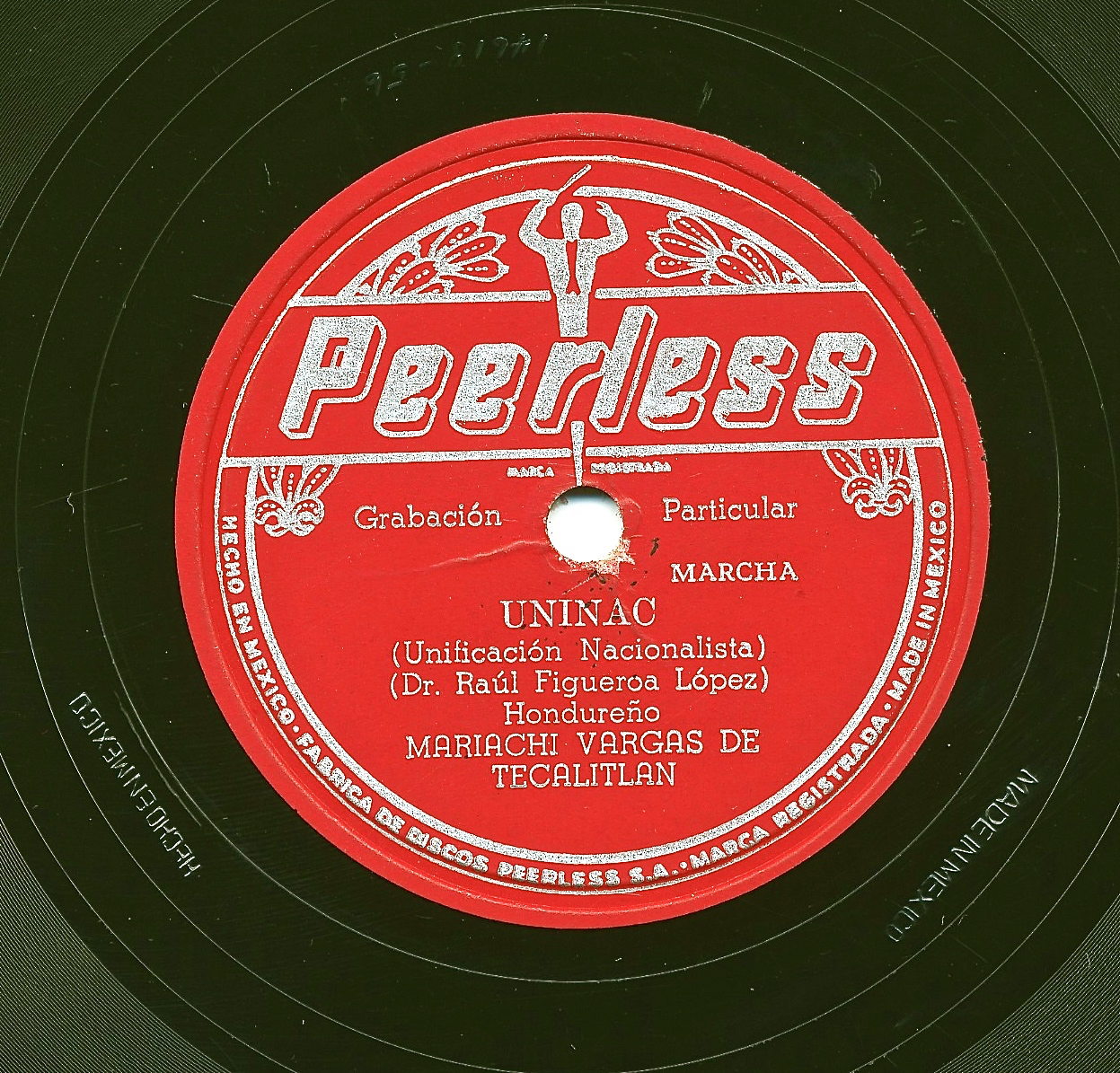

The label’s roster of stars over the first three decades was truly peerless. Aside from the big names already mentioned, its top artists also included Gonzalo Curiel, Lola Beltrán, Luis Arcaraz, Toña La Negra, Las Hermanas Aguila, Miguel Aceves Mejía, Emilio Tuero, Los Hermanos Záizar, Tata Nacho, Trío Garnica-Ascensio, and Ramón Armengod. The great Mariachi Vargas de Tecalitlán made its first recording on Peerless in 1937, according to Clark’s liner notes for an Arhoolie CD compilation of the group’s early recordings.

The label’s roster of stars over the first three decades was truly peerless. Aside from the big names already mentioned, its top artists also included Gonzalo Curiel, Lola Beltrán, Luis Arcaraz, Toña La Negra, Las Hermanas Aguila, Miguel Aceves Mejía, Emilio Tuero, Los Hermanos Záizar, Tata Nacho, Trío Garnica-Ascensio, and Ramón Armengod. The great Mariachi Vargas de Tecalitlán made its first recording on Peerless in 1937, according to Clark’s liner notes for an Arhoolie CD compilation of the group’s early recordings.

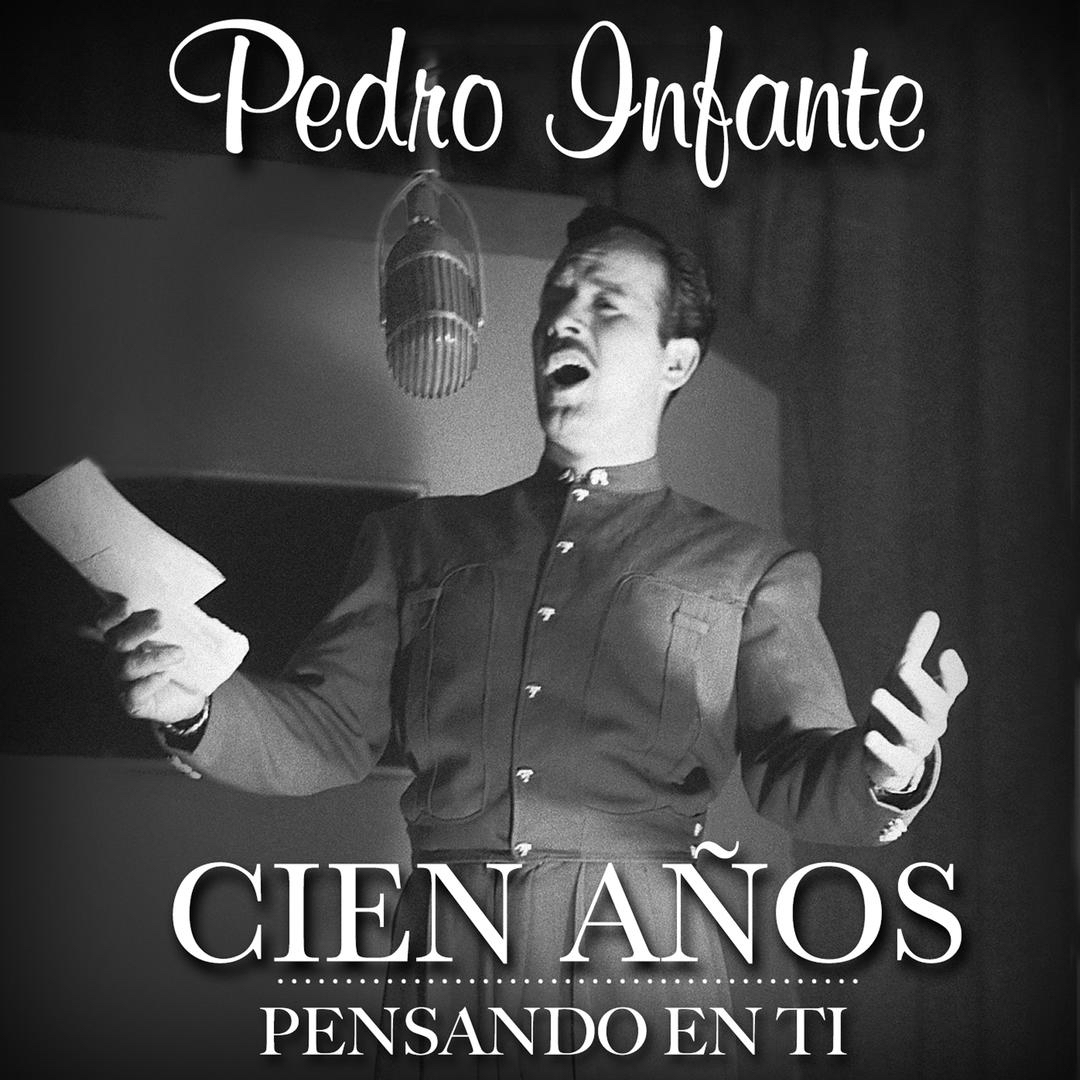

But there is one artist that helped cement the company’s fortune and its future: singer, actor, and cultural icon Pedro Infante.

“Peerless finally hit real gold,” writes Strachwitz, “when, under the artistic direction of Don Guillermo Kornhauser, it recorded the soon-to-be #1 Mexican singing and movie idol, Pedro Infante, on November 5, 1943.”

One of the most fruitful sources of information at Peerless was its studio ledger books, with chronological information about recording sessions. Those hand-written ledgers included three volumes covering the period from 1945 through 1958. The entries included detailed information about recording dates and matrix numbers, as well as technical data, including hand-drawn diagrams showing the type and location of microphones used during the sessions.

Clark, who remained in Mexico a full month, much longer than the others, began transcribing the wealth of data in the studio ledgers, with the help of a paid assistant. But the work was suspended because it was slow going and Strachwitz wanted to focus instead on completing the basic catalogue, focusing on the 78-rpm era up to 1955.

According to Clark, Ulrich later provided photographs of the ledger pages for future transcription, including pages from the middle volume (1951-1954) that was believed lost at the time, but was later recovered.

The studio session ledgers, however, were only one source of information available to the team. They had other ways of documenting and crosschecking the label’s recording history.

There was the library-style card file, with one card for each recording. There was the label copy, containing the exact information sent to the printer for typesetting the labels, all kept in in bound binders in a filing cabinet. And there were files with information about royalties paid to the artists, noting the composer, the publisher, and the royalty agreement.

There was the library-style card file, with one card for each recording. There was the label copy, containing the exact information sent to the printer for typesetting the labels, all kept in in bound binders in a filing cabinet. And there were files with information about royalties paid to the artists, noting the composer, the publisher, and the royalty agreement.

Finally, there was a storage room for the old phonograph records themselves.

Writes Strachwitz: “A very small room, partitioned from a larger space, contained the most interesting artifacts from my standpoint – namely 78 and 45 rpm discs pressed by Peerless after 1939. The run of Peerless pressings seemed to be complete, in chronological order, neatly stored in albums holding about 10-12 discs each. All discs were in mint condition – file copies – one example of each.”

The process of documenting the discs was also slow and tedious.

“We had to take a laptop into the vault itself and sit at a little table, and pull out all the records one by one,” recalled Clark. “So I read off the label information to my assistant, who typed everything into the database.”

As a curious footnote, the researchers also found some copies of those early recordings made by Baptista on his original pre-Peerless labels.

“The discs were the oldest information we could find,” said Clark. “They started much earlier than any of printed documentation. There were a few really old discs in that archive, even a few Artex and Huici and Nacional, which were the predecessors to Peerless.”

So far, the Peerless Discography stops in 1955 with a 78-rpm ranchera recording by Las Hermanas Segovia (Peerless No. 4948). The mid-1950s marked the end of the era of 78-rpm discs, when they began to be replaced by the smaller 45-rpm singles, although there were exceptions. Peerless and other Mexican labels continued to produce some 78s in limited quantities even through the 1960s, primarily to service jukebox operators in rural areas who avoided the expense of updating their machines to the new format.

In the latter half of the 20th century, Discos Peerless lost sales and stature in a rapidly changing music industry. Pop tastes had become gradually more pop and less folkloric, more foreign and less national.

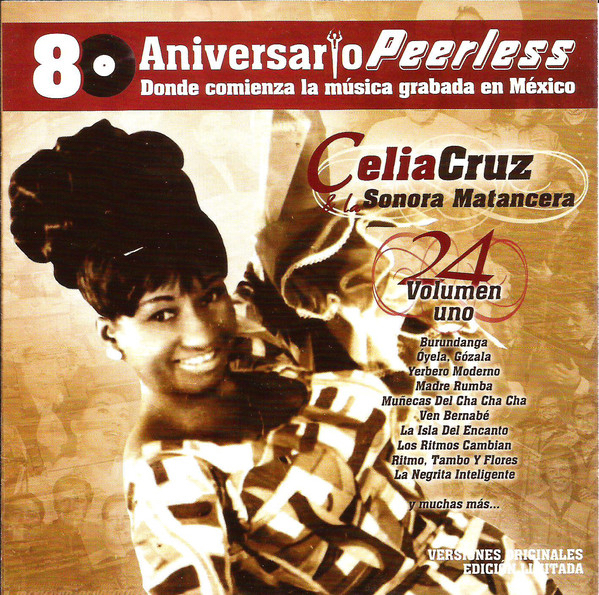

Peerless could not keep up. But it wasn’t for lack of trying. The label moved into other genres: tropical with Celia Cruz, “grupero” style with Los Babys and Los Freddys, and romantic pop with Verónica Castro.

The firm also licensed recordings from international labels for domestic distribution. They brought in classical music from Deutsche Grammophon, pop artists from England on British Decca, and sizzling salsa sounds from Colombia on the legendary Discos Fuentes.

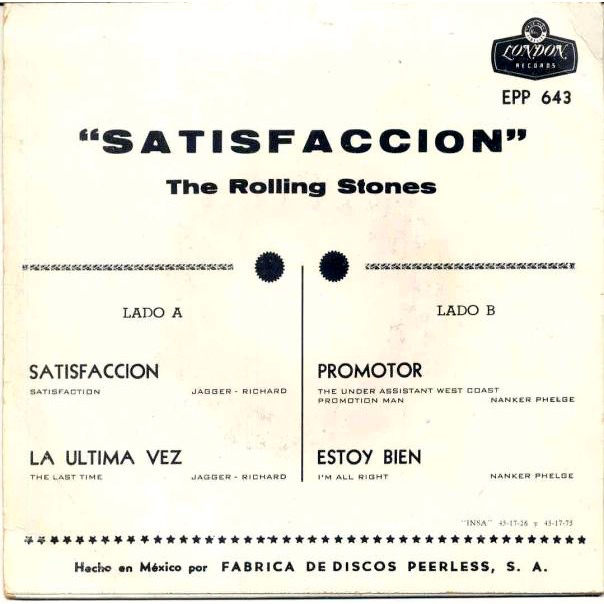

Peerless released music by easy-listening bandleader Mantovani and sex symbol Tom Jones. And it also issued late-term 78-rpm pressings by The Rolling Stones that, as Strachwitz notes with amazement, “were indeed available in Mexico in that format at that late date!” Clearly a rock collector’s dream, he adds.

“We wanted to offer the country a total musical and cultural experience,” Ulrich told Excelsior. “That was the vision of our founder.”

“We wanted to offer the country a total musical and cultural experience,” Ulrich told Excelsior. “That was the vision of our founder.”

Still, the decline and fall of Discos Peerless was long and painful.

“They kept trying and trying and trying to come up with a new formula, sign new artists, come up with a big hit,” said Clark, “but they just weren’t successful. By the mid-1990s, they were in real bad shape. All of the evidence was of a company in decadence.”

Keeping up with music trends was only one challenge. The label also faced staggering losses from rampant record piracy, and the looming threat of the digital revolution in the recording industry. Ulrich and the family had a meeting and decided to sell. In 2001, Peerless was bought by Warner Music, which has re-packaged and re-released the label’s rich and deep repertoire.

For posterity, the label’s legacy will be enshrined in the discography.

As a final resort in the effort to create that comprehensive catalogue, Strachwitz appealed to private record collectors for help. Those who provided crucial information included Armando Pous, “probably Mexico’s leading record collector,” said Strachwitz. Pous was especially helpful in filling gaps for that lost period before 1939.

Yet, there are still more gaps to fill, more recordings to be added.

“We hope that collectors who have items, for which our discography lacks data, will send us all details and thereby contribute to the eventual completion of this first part of the Discos Peerless discography,” Strachwitz writes..

The collector’s plea echoes the one made 90 years ago in Compton Mackenzie’s editorial: “Now, who will volunteer for this noble but arduous task?”

– Agustín Gurza

1 Comments

Stay informed on our latest news!

Clarification on Peerless Discography

by Chris Strachwitz (not verified), 09/13/2019 - 18:18When Peerless started again in 1939 with matrix number 1 -39, that meant the master (or matrix) was indeed # 1 - and was recorded in 1939. It may also have been first released or issued in 1939 since most records in those days were often released within 6 months of recording. But in many cases, a recording was first issued at a much later date and sometimes even not until the LP or vinyl era. The matrix number is the all important ID of a unique performance, even though that performance may not have been issued until much later, or on a different catalog release series, or even on a different label, or even licensed to another company! In many cases, a song or recording which became famous or a big seller, may also see new or re-recordings at later dates!