Editor’s Note: In this part of the story about La Adelita, we meet some of the real soldaderas recognized as revolutionary leaders, review some of the sexist portrayals in modern media, and close with the restoration of this woman warrior as a universal symbol of liberation.

Editor’s Note: In this part of the story about La Adelita, we meet some of the real soldaderas recognized as revolutionary leaders, review some of the sexist portrayals in modern media, and close with the restoration of this woman warrior as a universal symbol of liberation.

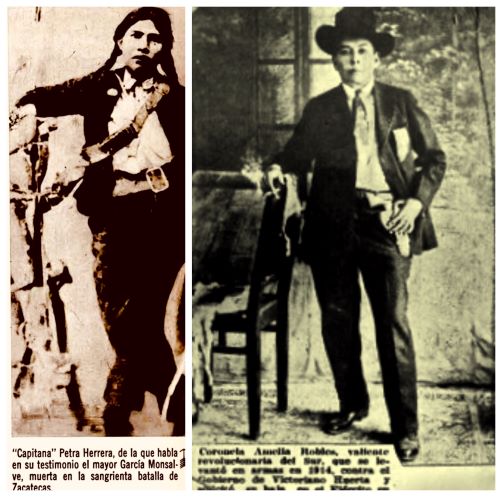

Coronelas and Generalas: Name, Rank, and Newspaper Coverage

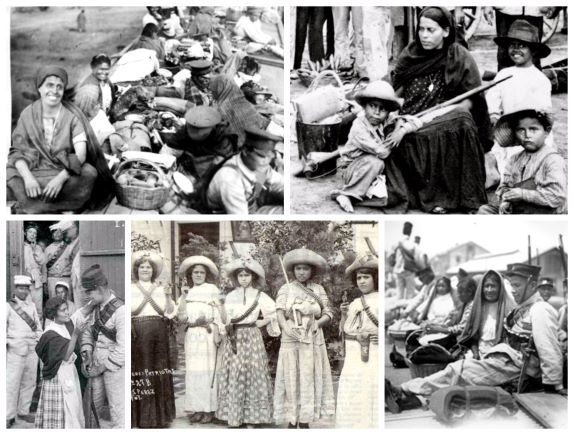

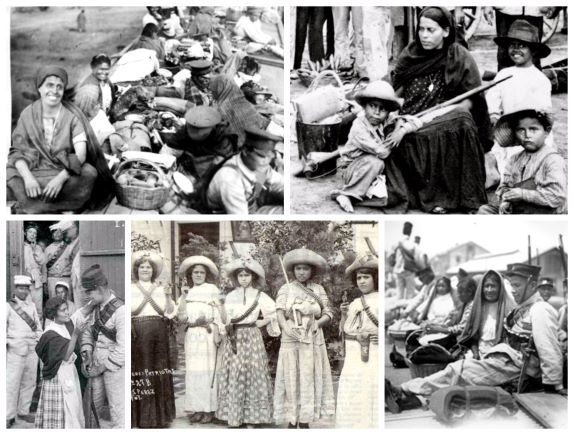

It was common for some soldaderas to join the battle spontaneously, taking up the rifles of their fallen husbands. Others planned in advance to be fighters and went out of their way to gain acceptance as combatants alongside the men.

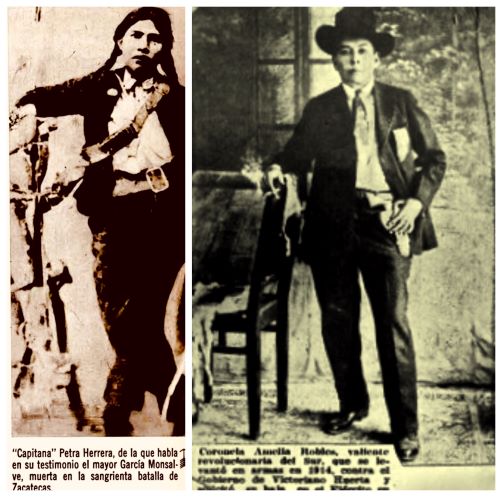

Some women changed their names and disguised their appearance to pass as men, lowering their voices, tightly wrapping their breasts, and donning men’s clothing. A few even rose to the rank of coronelas, leading their own units and gaining wide respect from the troops and the brass.

The stories of these female revolutionaries may not be well-known by the general public, but they are well-documented by historians. A handful even had corridos written about them, as noted by María Herrera-Sobek in her book,

The Mexican Corrido: A Feminist Analysis. (Indiana University Press, 1990).

A soldier named Petra Herrera, who had changed her identity to Pedro, is the only woman mentioned by first and last name in a revolutionary composition, titled “Corrido del Combate del 15 de Mayo en Torreon.” She is cited for being a valiant leader, the first to enter the fight ahead of her men, unwilling to accept defeat even after falling prisoner.

La valiente Petra Herrera

Al combate se lanzó,

Siendo siempre Ia primera

Ella el fuego comenzó.

Herrera, known for her skill in blowing up bridges, is mentioned by name in two other corridos about the same battle. In "Corrido de la Toma de Torreón,” she is hailed as the leader of a midnight raid on City Hall, precisely on the eve of the big battle.

El día 14 a medianoche

Entraron con gran violencia

Petra Herrera en adelante

A la mera presidencia.

Her bravery is cited again in “Corrido de las Hazafías del General Lojero y la Toma de Torreón por el Ejército Libertador.” Her bold defiance despite being captured is depicted as the final battle cry that inspired her troops to fight on, and the federales to flee.

La valiente Petra Herrera

En el fragor del combate,

Aunque cayó prisionera

Ni se dobla, ni se abate.

Despite Herrera’s leadership in winning this decisive battle in 1911, Pancho Villa refused to promote her to general, a rank routinely denied women on both sides. Resentful, Herrera broke away and formed her own all-woman army, bestowing on herself the rank she felt she had earned.

Unfortunately, Herrera did not have a heroic end. After her fighting force was disbanded, she served as a spy for revolutionary leader Venustiano Carranza, working as a bartender in Ciudad Jiménez, Chihuahua. She died there after being shot three times, not by enemy agents, but by drunks in a bar fight.

Just three other corridos depicting battle scenes mention women soldiers by name, writes Herrera-Sobek, longtime Chicano Studies professor at UC Santa Barbara. Yet, even in those ballads – “De Agripina,” “Corrido de la Toma de Papantla,” and “El Coyote” – the women are identified only by first name or nickname.

The absence of surnames, of course, contributes to the anonymity.

Other corridos mention only generic

soldaderas. For example,

“La Toma de Zacatecas” talks about women fighters as pretty and gutsy (

“eran todas muy bonitas, y de muchos pantalones”). And the “Corrido de la Muerte de Emiliano Zapata” mentions a nameless woman spy who tried to warn Zapata of his impending ambush and assassination.

One more celebrated soldadera stands out in the history of the Revolution – Amelio Robles Avila. Born as a female named Amelia, Robles assumed a male identity after joining the forces of Zapata in the South. Nicknamed El Güero, he distinguished himself in battle as el coronel Robles,” winning Zapata’s admiration. Robles kept living as a man after the war, unlike many soldaderas who resumed their lives as women. He later married a woman named Ángela Torres and the couple adopted a child. Robles was showered with honors from three Mexican presidents and today is considered the first transgender person to be officially recognized in Mexico.

Major media in the United States also took notice of the skill and leadership displayed by the most notorious Adelitas.

On August 18, 1911, under a headline that reflects the unabashed paternalism of the day –

“Mexican Rebels Have Girl Leader” – the

Washington Herald reported on a battle in Morelos led by a fierce Mayan soldier, Margarita Neri, who commanded an Army of Indian women. This “girl leader,” who had killed her own husband, was known for her cold-blooded cruelty, according to Reséndez. She was so feared that the mere word of her approach prompted the governor of Guerrero to flee in a shipping crate. Neri was eventually executed.

On March 14, 1915, the

San Francisco Call reported on a visit by a

soldadera commander under the headline: “

Mexico Joan of Arc Here to Buy Guns for Her Soldiers.” Colonel Ramona de Flores, “the only woman officer In the Carranza army, who at 30 is a veteran of forty-seven battles,” arrived in San Francisco on the steamer Balboa, shopping for weapons and supplies for her army of 2,000 men. The newspaper reports that Flores had joined the Revolution after her husband was killed in battle. “Bent upon revenge the widow gathered a score of Yaqui Indians employed upon her plantation and made a march into the enemy’s territory. Her followers grew and within six months she had more than 1000 men.” The article closes with a quote from La Coronela herself, translated through an interpreter: “I am fighting for freedom now and my 2000 soldiers won’t quit until we get it — and I won’t either.”

Other revolutionary women had direct ties to California. Angela “Angel” Jiménez, of Zapotec Indian descent, joined the fighting after witnessing the attempted rape of her sister, who then shot a federal soldier before killing herself. “Lieutenant Angel” was wounded in battle and eventually immigrated to San Jose where she became a supporter of the Chicano Movement. And Manuela Oaxaca, who was wed to a revolutionary soldier on a troop train, became pregnant and moved to Los Angeles to have her son, who grew up to be a famous actor named

Anthony Quinn.

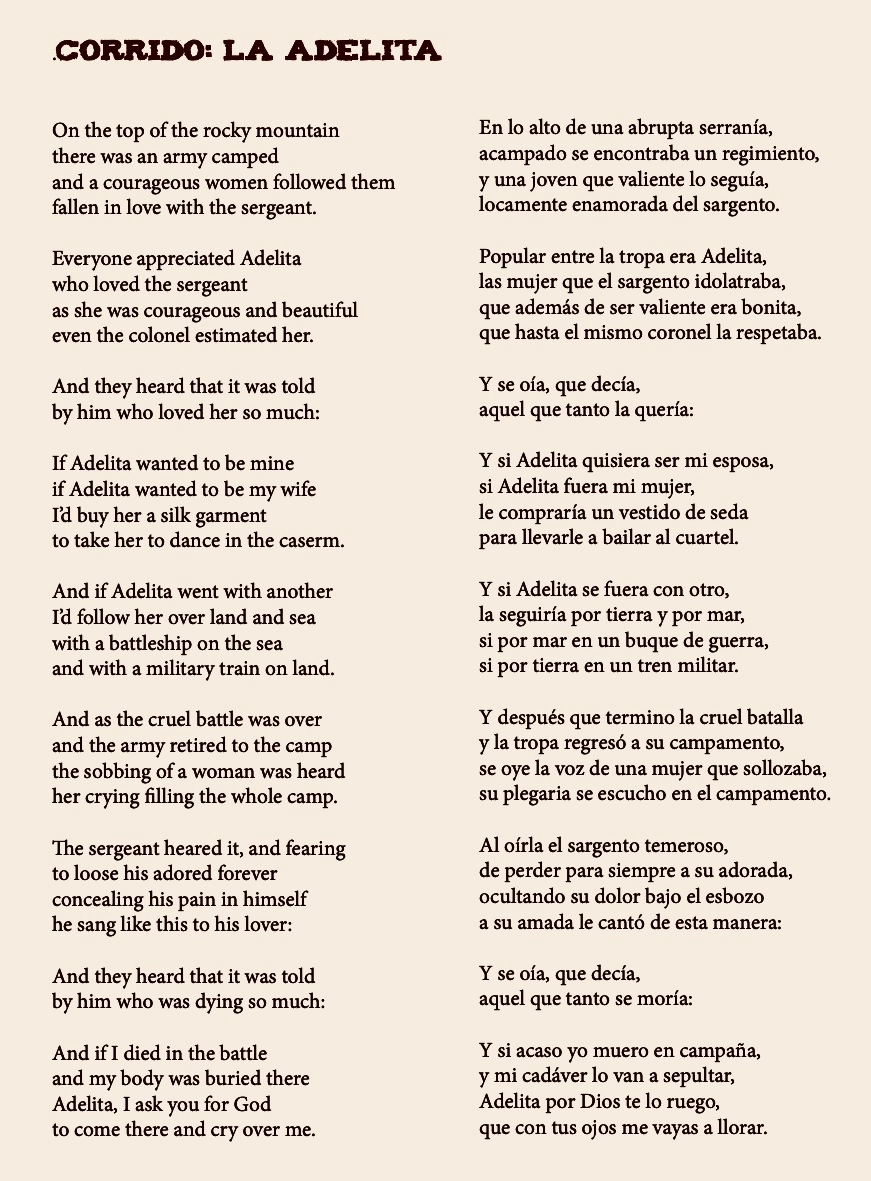

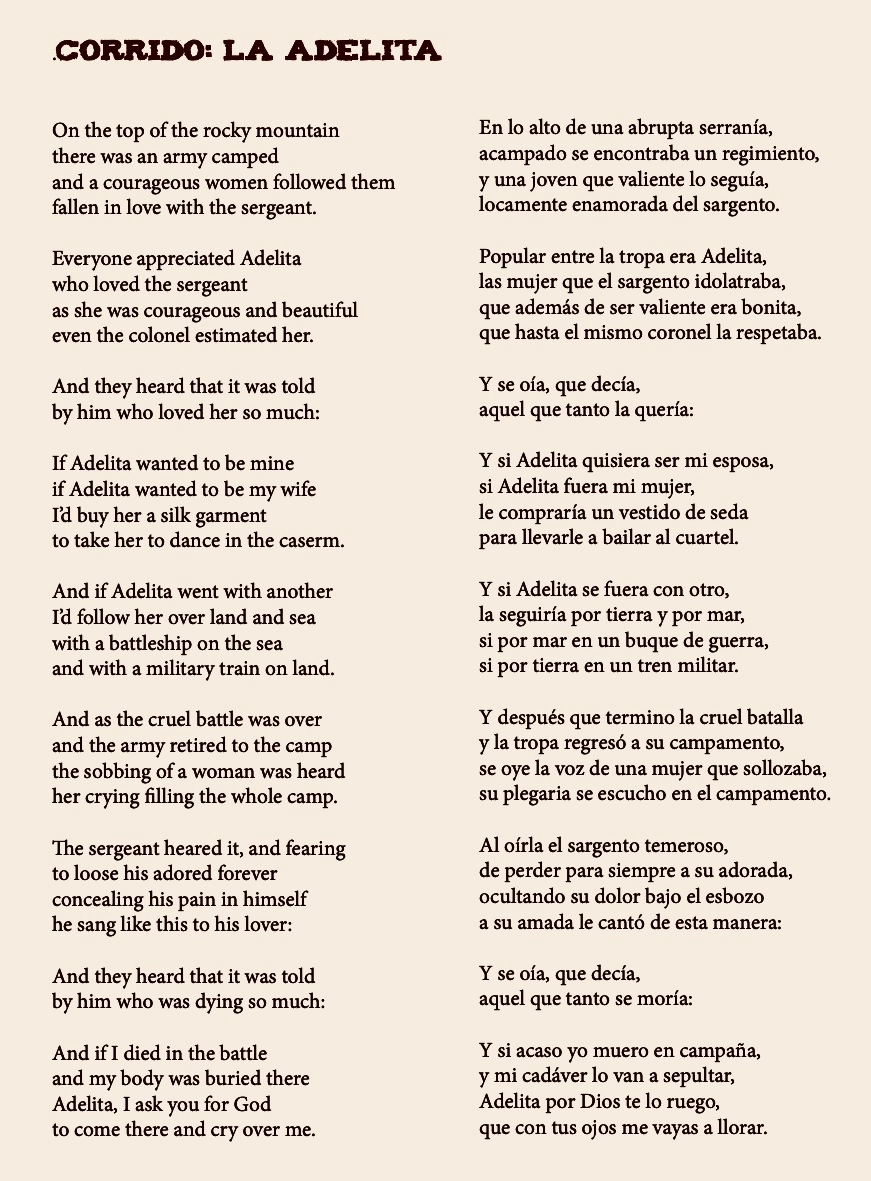

Happy Corrido, Harsh Realty

Knowing the truth about these brave soldaderas and the extent of their sacrifice, makes the famed corrido take on a truly trivial tone. “La Adelita” is not an homage that highlights their contributions; it is a pop ditty that erases them, masking reality with a catchy melody, bouncy step, and simple end rhymes.

The beloved corrido easily stirs feelings of pride and patriotism, as long as one doesn’t stop to analyze the lyrics. As many writers have noted,

La Adelita is seen exclusively from a man’s perspective, only as an object for his possession, admired for her beauty as much as her bravery. And if she were to go off with another man, as the lyric asserts, the suitor vows to follow her by sea or by land to take her back and make her his own.

Today, that vow would be considered criminal stalking. The idea of pursuing a woman to the ends of the earth, despite her rejection, may have rung romantic as an outdated Fifties fantasy. But by contemporary norms, it’s downright creepy.

Broadly speaking, the Revolution did not do much to change the status of women in Mexican society. Even those who had fought with distinction had to fight to be acknowledged as veterans and receive pensions. The average, unknown Adelita found that serving as the wife, daughter, or sister of a male soldier carried no benefits after the fighting stopped. Many lived out their lives in poverty or emigrated to the United Sates to find a new chance for survival.

“The contribution of women during the Mexican Revolution was undeniable, but at the war’s end, most had to resume their traditional roles as wives and mothers,” writes Maura Hohman in a

2018 article on History.com.

The legacy of Las Adelitas is being reassessed by historians and political analysts, sparked to some degree by celebration of the 2010 centennial. Established writers have published books, and young women scholars have taken up the topic in their graduate dissertations.

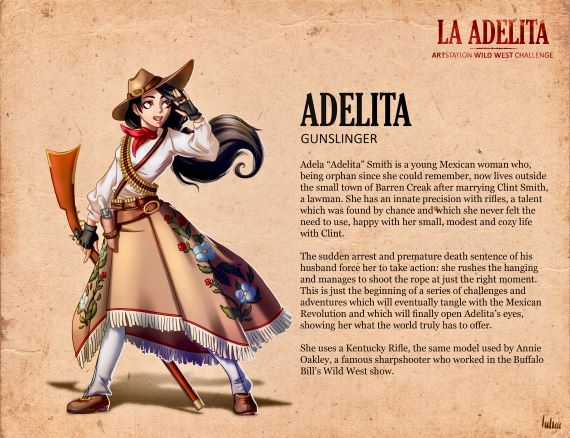

The new analysis aims to restore the reputation of the soldaderas, as well as their rightful place in history. The first step starts with a critique of the prevailing image of

La Adelita in contemporary culture – sexy, seductive, beautiful, alluring, and impeccably coiffed with silky, flowing hair straight out of a Breck shampoo commercial.

“Clearly this woman does not resemble the actual soldadera,” writes Delia Fernández, assistant professor of history at Ohio State University, in her study, "

From Soldadera to Adelita: The Depiction of Women in the Mexican Revolution" (2009, Grand Valley State University). “This romanticized depiction of the soldadera highlights her sexuality and omits her bravery… Despite the soldaderas’ efforts to support the Revolution and pursue equality, their memory has been replaced by the idealized one that men have conjured up in their imagination.”

Modernized Adelitas in Pop Culture

Today, the commercialized concept of La Adelita has become a full-blown brand, infiltrating many aspects of pop culture. Myriad products and places carry her name and image. Here are just a few examples found on the Internet:

•

Adelita y las Guerillas, a weekly comic book series launched in 1939 as the first in Mexico to feature a female superhero.

•

Adelita’s Way, a Las Vegas punk band, named after a bar in Tijuana, where the bandleader once met a woman who provided the inspiration.

•

La Adelita Tequila from Los Altos of Jalisco, “a renegade persona representing some truly exceptional tequilas.”

•

Adelita La Fashionista, a chic, western-style clothing line from Texas, much too sophisticated for a battlefield.

•

Colegio Adelita, a Spanish-language school in Guanajuato, thus named because it was founded in 2010, the revolution’s centennial year.

•

La Adelita Restaurant and Bakery, located in L.A.’s Pico-Union district, one of scores of eateries that feature the stylized soldadera image in logos, on menus, and wall art.

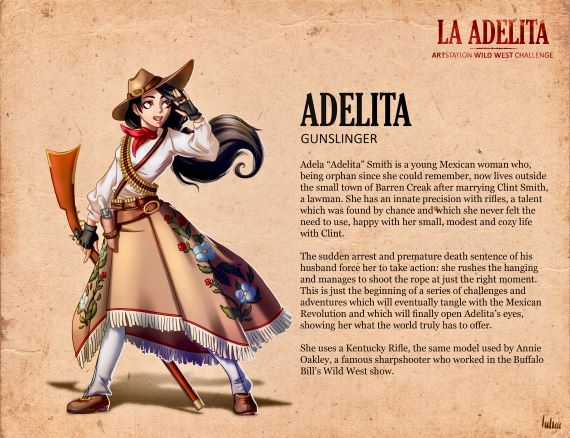

Adelita Smith,

Adelita Smith, a fictional character created by a female illustrator in Milan, Italy, is an international, cultural mash-up. This slim, doe-eyed, cartoon soldadera is the main character in a proposed story, set in Southern California on the eve of the Mexican Revolution. Adelita, married to a retired American lawman named Clint, is a precocious sharpshooter who carries a Kentucky Rifle, a la Annie Oakley.

The sexualized portrayal of

La Adelita has been projected globally via Hollywood movies, well into the 21

st century. In the 2006 film

“Bandidas,” celebrity co-stars Salma Hayek and Penelope Cruz are typecast as gorgeous, gun-toting women, once again reflecting figments of the male imagination.

These bosomy characters, writes Marilyn La Jeunesse in a 2019 article for

Teen Vogue, “with their waist-cinching corsets, plunging V-neck blouses, cowboy hats and revolvers, are the stereotypical epitome of what a Latinx woman — specifically Mexican women — are supposed to be: sexy and dangerous.”

But above all, attainable and tamable.

The legacy of Adelita fared no better in movies made in Mexico during the country’s so-called golden era of film.

María Félix, the sultry Mexican superstar, starred in

La Cucaracha (1958) as “the hard-fighting, rifle-wielding, drinking, cursing, but also promiscuous Cucaracha” of the title, as described in the essay

“Revolutionary Mexican Women in History and Film,” posted as part of an online history project at Arizona State University. La Cucaracha competes for the love of one Coronel Zeta, but loses to her rival, a weepy widow played by Dolores del Rio. The lesson: men prefer traditional, feminine women rather than aggressive female fighters

con cojones, to use the vernacular term for brave or daring. Accordingly, the spurned Félix character, pregnant with Zeta’s child, abandons the battle, and joins the camp followers to assume a more domesticated role.

Felix, who became a Hollywood star, appeared in more than half a dozen movies, from 1946 to 1971, about the Mexican Revolution. In Enamorada (1946), directed by Emilio “Indio” Fernández, she plays the daughter of landed gentry who is “tamed…like a wild mare” by a revolutionary commander, as the Arizona State website puts it. She defies her family, leaves her “goofy-kind-of-gringo” fiancé, switches her social-class allegiance, and walks off to join the Revolution, striding on foot alongside her man’s horse.

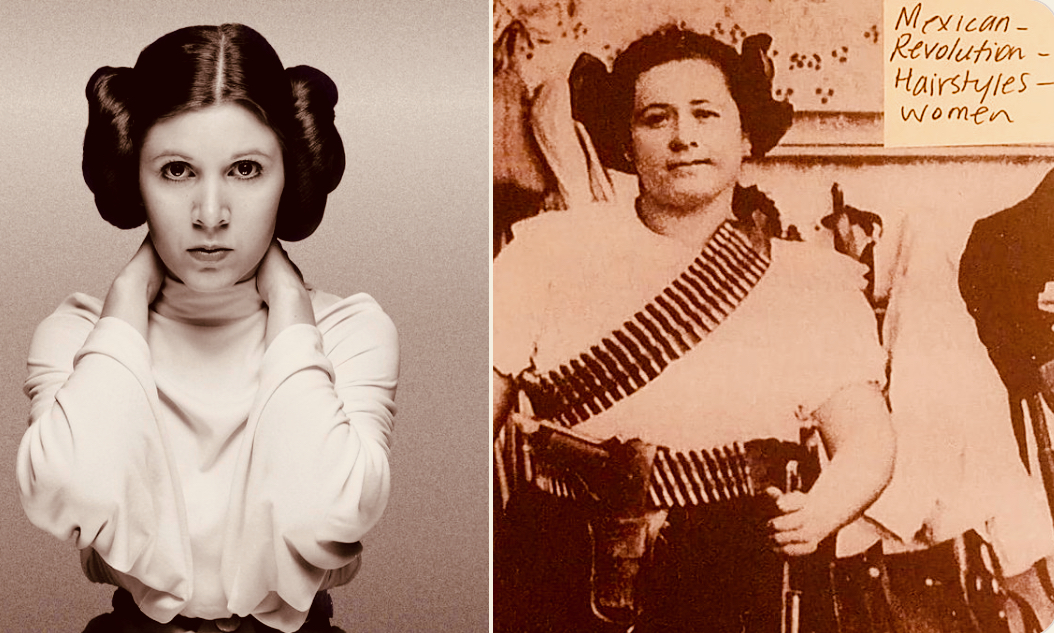

There’s one minor but remarkable footnote on Adelita’s film influence.

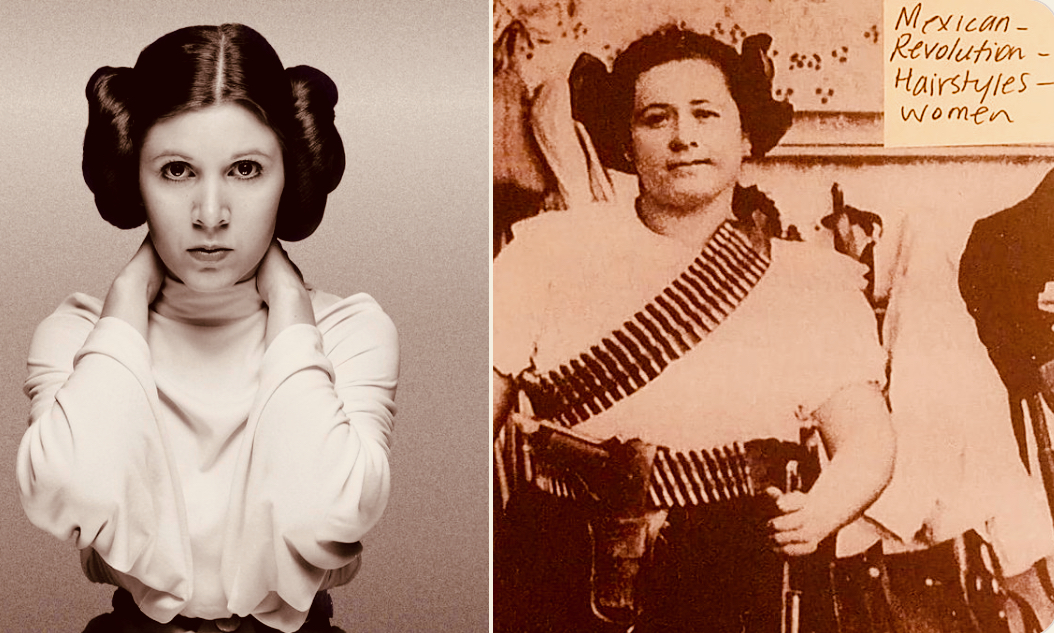

Star Wars creator George Lucas was

inspired by soldaderas when he created the double-bun hairstyle for Princess Leia, played by Carrie Fisher. In trying to create a different look that was anti-fashion, the famed director told

Time in 2002 that he “went with a kind of Southwestern Pancho Villa woman revolutionary look.” In 1977, Fisher explained the fashion strategy to the BBC, saying, “George didn’t want a damsel in distress, didn’t want your stereotypical princess. He wanted a fighter, he wanted someone who was independent.”

Meanwhile, on the musical front, the iconic corrido in honor of

La Adelita has been recorded hundreds of times around the world, often as an instrumental, divorced from any revolutionary meaning. There are versions by Mexico’s legendary singer

Jorge Negrete, U.S. folk trio (in English)

The Kingston Trio, Chile’s New Song ensemble

Inti-Illimani, the Latin big band of

Xavier Cugat, Argentina’s alt-Latino artist

León Gieco, American crooner

Nat King Cole, norteño duo

Los Alegres de Terán, Tex-Mex outfit

Country Roland Band, French orchestra leader

Franck Pourcel, Chicano folk/rock singer

Trini Lopez, and contemporary mariachi vocalist

Pepe Aguilar.

The 82 recordings in the Frontera Collection range in style from marching bands and norteño groups to mariachis and instrumental orchestras. They appear under four different tiles in the database, though they’re all the same song, with variations. There are 49 tracks with the singular

“La Adelita,” 21 with her name but no article,

“Adelita,” eight using the plural name,

“Las Adelitas,” and four titled

“La Nueva Adelita.” Two of these tracks are of special interest.

The versions by San Antonio singer Lydia Mendoza were performed April 10, 1982, in Wheeler Auditorium at UC Berkeley and recorded live by Chris Strachwitz for Arhoolie Records. The CD of the concert,

“La Alondra de la Frontera – LIVE!,” is available from Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

Another version, by the

Trio González on the Victor label is of historic significance. It’s considered the first recording of the song, and it contains a small but revealing change to one word in the familiar lyrics. In the standard line, the besotted sergeant vows, if Adelita should marry him, to buy her a silk dress and take her to “dance” at the barracks (

“para llevarla a bailar al cuartel”). On the original 78-rpm disc, recorded Dec. 22, 1919, the plan changes; he wants to take her to “sleep” at the barracks (

“Y la llevaba a dormir al cuartel”).

As with so much surrounding this song, the who-why-and-when of this significant change is unknown.

An Enduring Inspiration

Despite the distortions of revisionist pop history, La Adelita endures as a powerful symbol for women today. Looking back on her history, separating fantasy from reality, has become, not just an academic endeavor, but a healing exercise.

It starts with breaking the intellectual and cultural constraints of the past, as suggested by Alicia Arrizón, UC Riverside Professor of Gender and Sexuality Studies, in her essay

“My Love Affairs with Soldaderas,” which was written in conjunction with the 2015

Soldadera exhibition at East L.A.’s Vincent Price Art Museum.

“The act of revisiting the revolutionary Adelita/soldadera is a reminder that we are trapped in history, and history is trapped in us,” she writes.

Instead of rejecting the tarnished image of

La Adelita, women activists have restored and reclaimed it as a heroic, feminist symbol. During the Chicano Movement of the early 1970s in Southern California, a group of young women, led by activist

Gloria Arellanes of El Monte, broke away from the radical Brown Berets, discontent with its male leadership. They formed their own civil rights group for women and called it, Las Adelitas de Aztlán.

Their act of independence echoed the tactics of soldaderas who struck out on their own as revolutionary leaders.

“The revolutionary character of soldaderas is embodied in Dolores Huerta, Rigoberta Menchú, and Gloria Anzaldúa,” concludes Arrizón. “In Mexico and the U.S. today, the name Adelita has become an inspiration and a symbol for any woman who fights for her rights and social change.”

– Agustín Gurza

Add your comment