Artist Biography: Rumel Fuentes - Corridos, Chicano Politics, and the Birth of the Frontera Collection

This year marked the 50th anniversary of the National Chicano Moratorium, the massive anti-war march in East Los Angeles held on August 29, 1970. The milestone inspired major media retrospectives on the impact of this galvanizing demonstration, citing inroads made by Chicanos in politics, higher education, journalism, and the arts.

This year marked the 50th anniversary of the National Chicano Moratorium, the massive anti-war march in East Los Angeles held on August 29, 1970. The milestone inspired major media retrospectives on the impact of this galvanizing demonstration, citing inroads made by Chicanos in politics, higher education, journalism, and the arts.

In music, the 1970s saw a surge of Chicano and Latin rock bands from Los Lobos to Santana, as I discussed in a recent interview for La Plaza de Cultura y Artes, titled “Music of the Chicano Moratorium.” Among the artists featured in the podcast was a politically committed singer-songwriter from Texas named Rumel Fuentes, who never came close to achieving the fame of his California contemporaries.

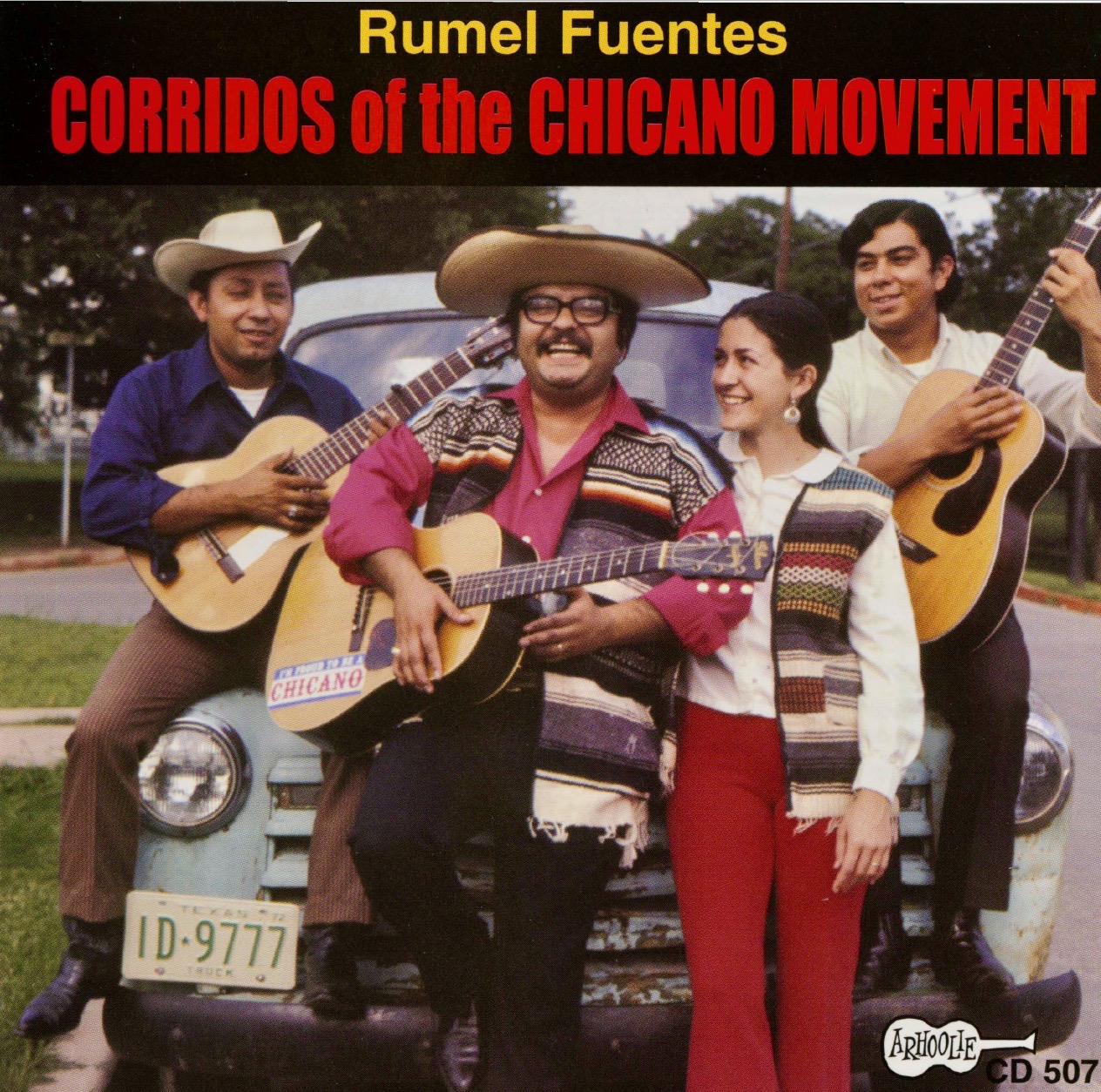

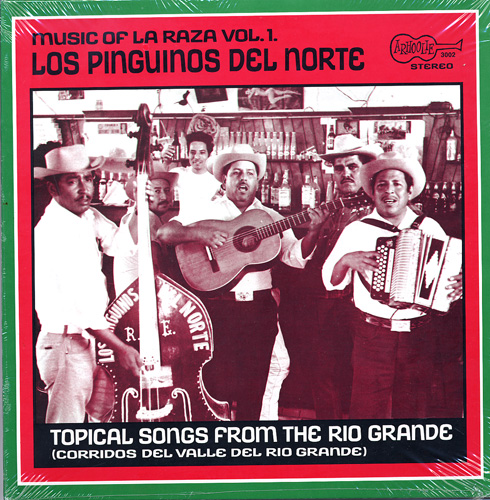

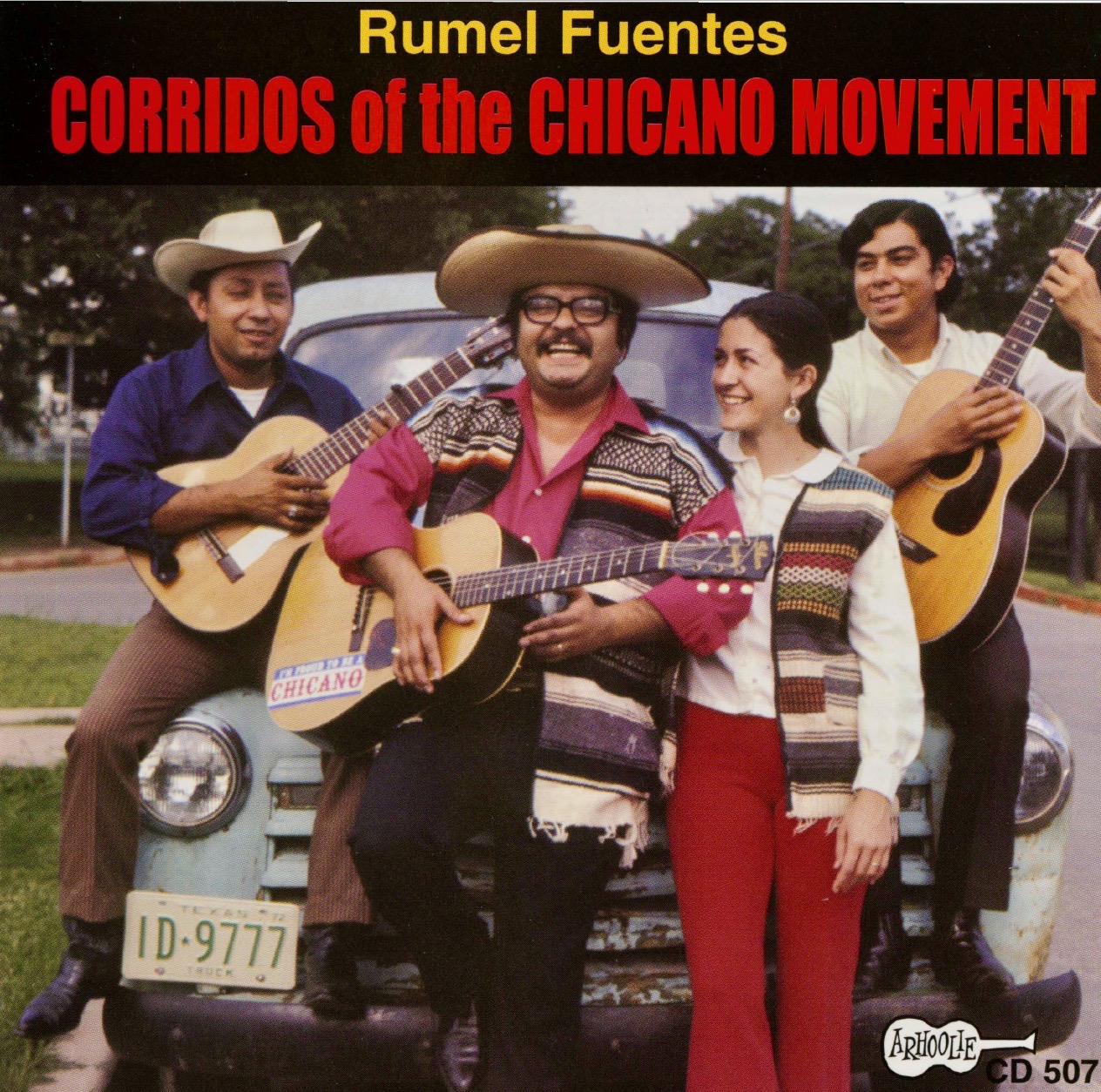

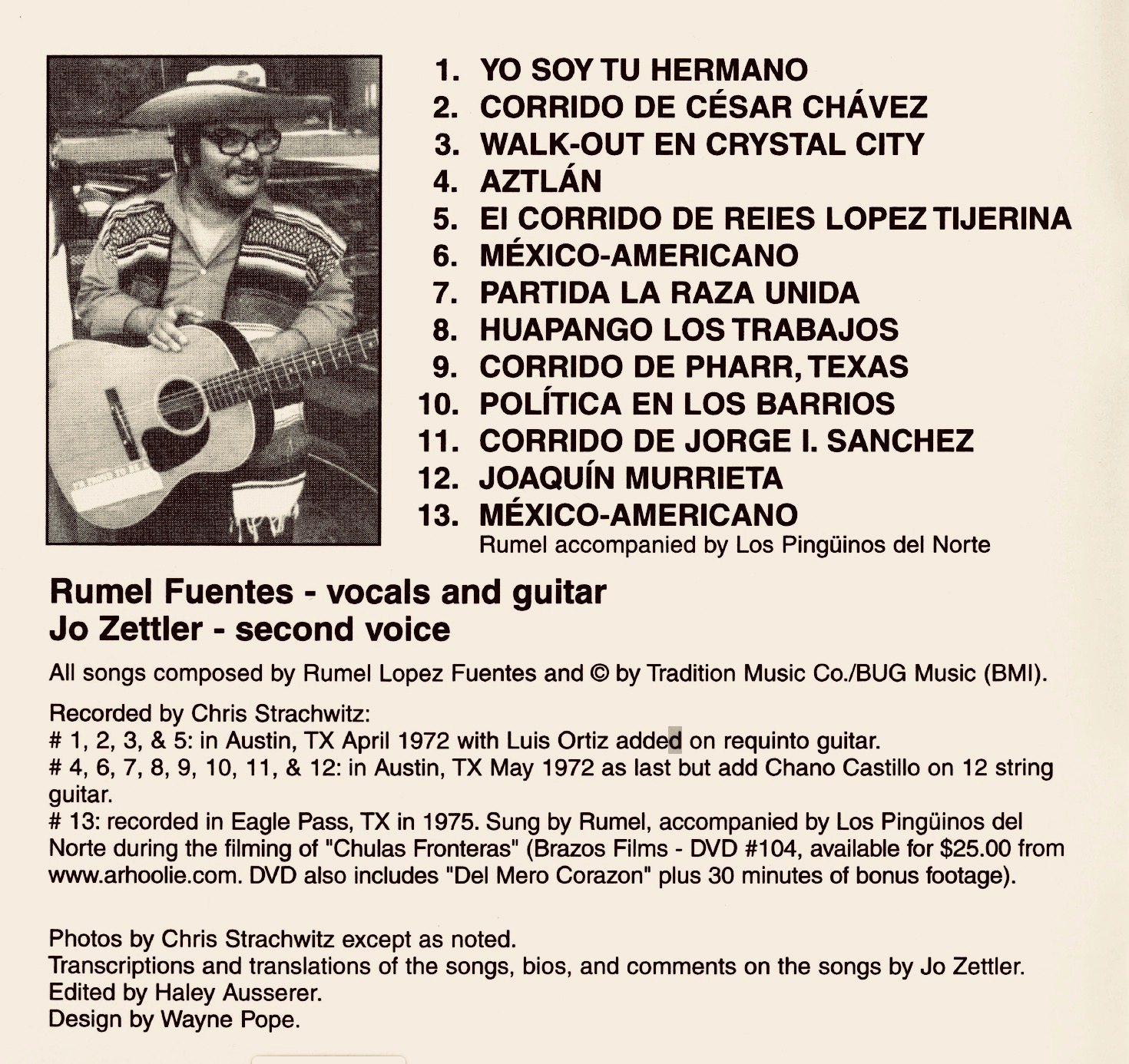

Fuentes’s music and memory would likely be long forgotten, in fact, were it not for a CD of his songs, Corridos of the Chicano Movement, released 11 years ago by Arhoolie Records, the label created by Chris Strachwitz. The relationship of Fuentes and Strachwitz, however, went far beyond producer and artist. It was a transformative collaboration between unlikely partners: a tall German immigrant who didn’t speak Spanish and a chubby Mexican American who was on a mission to recover his roots and assert his bicultural identity.

When they first met 50 years ago, the intrepid producer was anxious to explore the unknown world of Mexican music just across the border, so near yet so far for him. Fuentes would provide the needed entrée for Strachwitz, and their alliance would serve as a cornerstone of the private record archive that would become the Frontera Collection.

Born on the Border

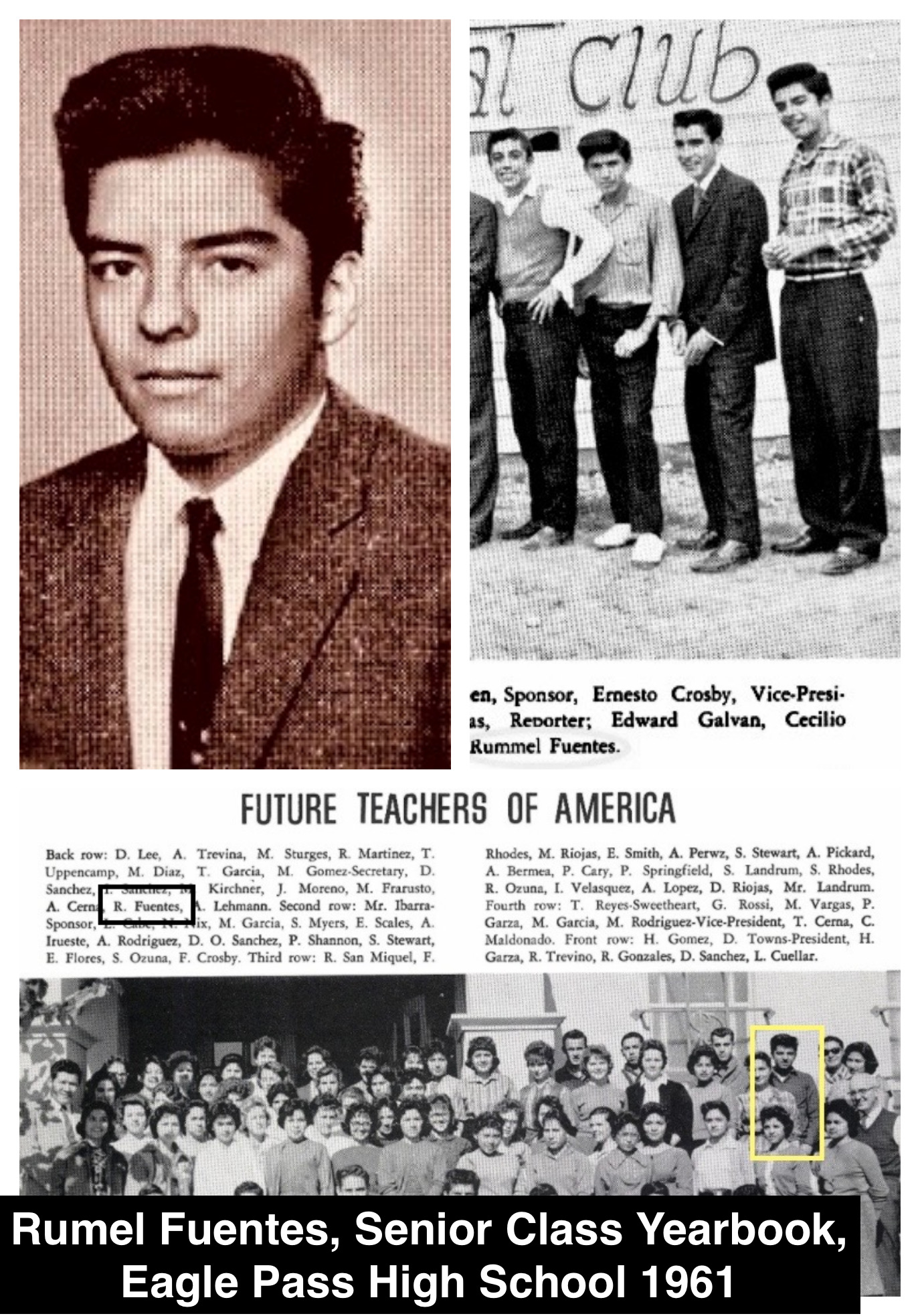

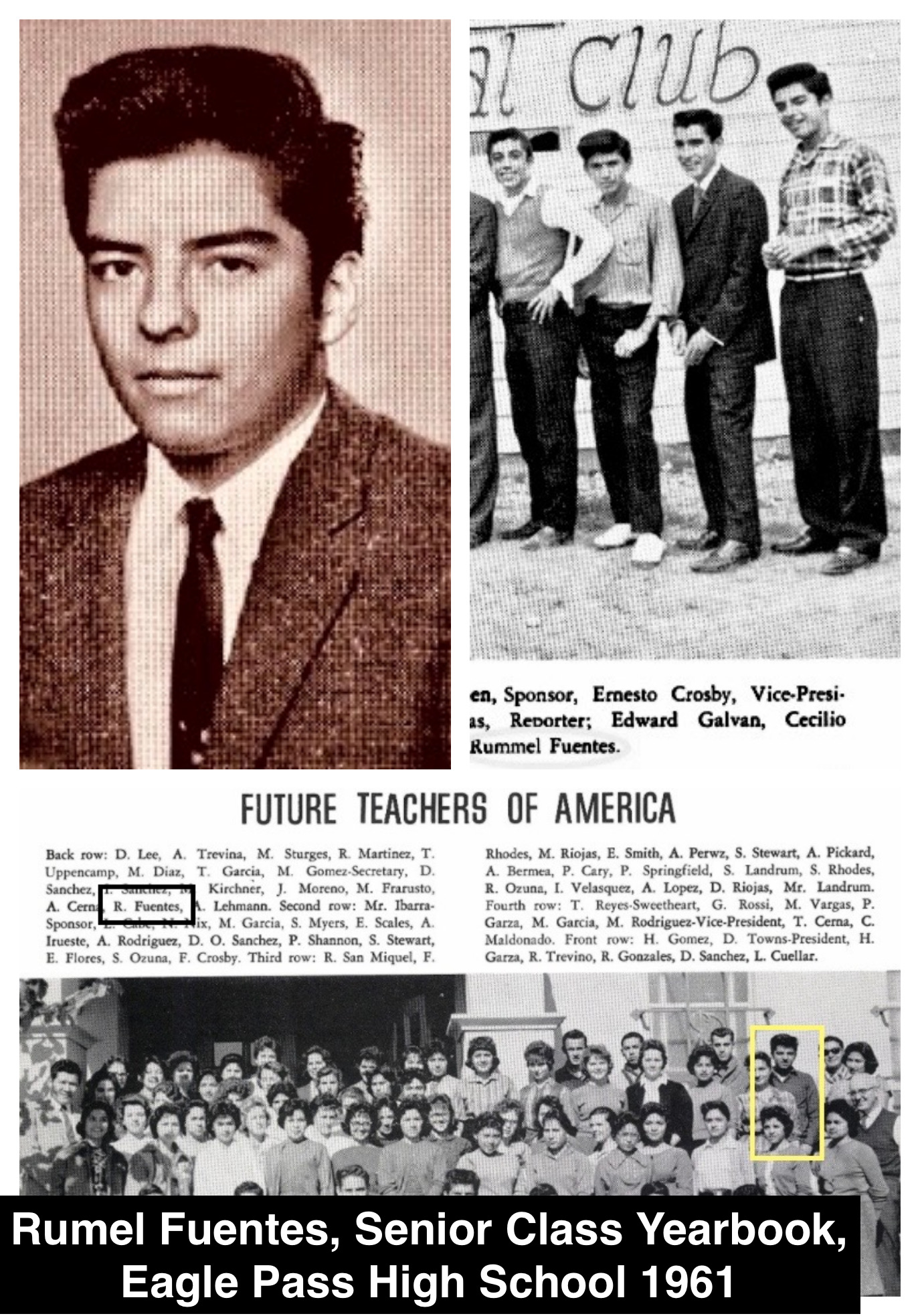

Rumel Lopez Fuentes was born on June 25, 1943, in Eagle Pass, Texas, a small town directly across the border from Piedras Negras, Coahuila. The ninth of eleven children, he was named after German General Erwin Rommel, christened reportedly by his older brother who served in North Africa during World War II.

Eagle Pass, the first American settlement on the Rio Grande, was once a busy frontier trading post. But during Rumel’s formative years in the 1950s, his hometown was shrinking, both in population and opportunities. Each year during spring and summer, his family would hit the migrant trail to Indiana and Michigan, seeking work on the fruit farms and canneries near the northern border with Canada. Michigan for years had actively recruited Mexican workers, especially from Texas, making the region a top magnet for migrant labor.

Fuentes came of age on the cusp of the Chicano Civil Rights movement, which would inform so much of his music. He was the only one in his family to earn a high school degree, graduating from Eagle Pass High School in 1961. His senior yearbook, El Cenizo, shows that the slender, handsome teenager took advantage of everything a secondary education had to offer.

Fuentes played football and tennis, performed in talent shows, and participated in the Halloween Carnival. As a senior, he sang in the school choir and joined the Vocational Industrial Club which, among other things, repaired Christmas toys for children. Reflecting his career ambition, he was also active in Future Teachers of America.

Musically, Fuentes was completely bicultural, like many inhabitants along the Rio Bravo. He dug the pop stars of his youth, like Bob Dylan and Johnny Cash, but he was also exposed to traditional Mexican music. From his father, he learned historic corridos, tales of daring and defiance rooted in hostile borderlands where encounters between American arrogance and Mexican resistance played out in violent ways. These narrative tales – which lionized folk heroes defending Mexican honor, often with their lives – would serve as a template for the young artist’s future songs in service of the new Chicano struggle for equality and fairness in American society.

Fuentes’s emergence as an artist coincided with the rebirth of Eagle Pass, which almost doubled its population between 1960 and 1980. But more importantly, the young artist matured at a time when the Chicano Movement was blossoming in his own backyard. He became an early supporter of La Raza Unida Party, a scrappy political faction founded in 1973 in nearby Crystal City. Its leader, local Chicano activist José Angel Gutiérrez, gained national fame as chairman of the short-lived party, which was outlawed by the Texas Legislature in 1979.

Gutiérrez was asked about his former comrade for an article titled “Defiant Artist Fuentes Getting His Due,” published in 2009 by the San Antonio Express-News on the occasion of the posthumous release of the Arhoolie CD. Looking back, he remembered the singer’s high-spirited personality.

"He was jovial, rotund, jolly, the Chicano Santa Claus, if you will," Gutiérrez was quoted as saying.

But Fuentes was dead serious about his music.

"The mainstream media didn't carry our stories unless they were negative,” continued Gutiérrez, who went on to become an attorney and tenured professor in political science at the University of Texas Arlington. “He told our stories. This was our validation. We didn't see ourselves in print. We didn't see ourselves in the movies. We didn't see ourselves in the newscasts. We saw ourselves when Rumel started singing.”

Activist and Songwriter

The traditional Mexican corrido, as I explain in a series of blog posts from 2017, tells stories of epic events, such as the Mexican Revolution, and heroic folk heroes, such as the border bandits of the late 1800s, which were common when the song style first appeared. They also spoke of the tragedies and conflicts that engulf regular folk who must rise with courage to meet their destiny.

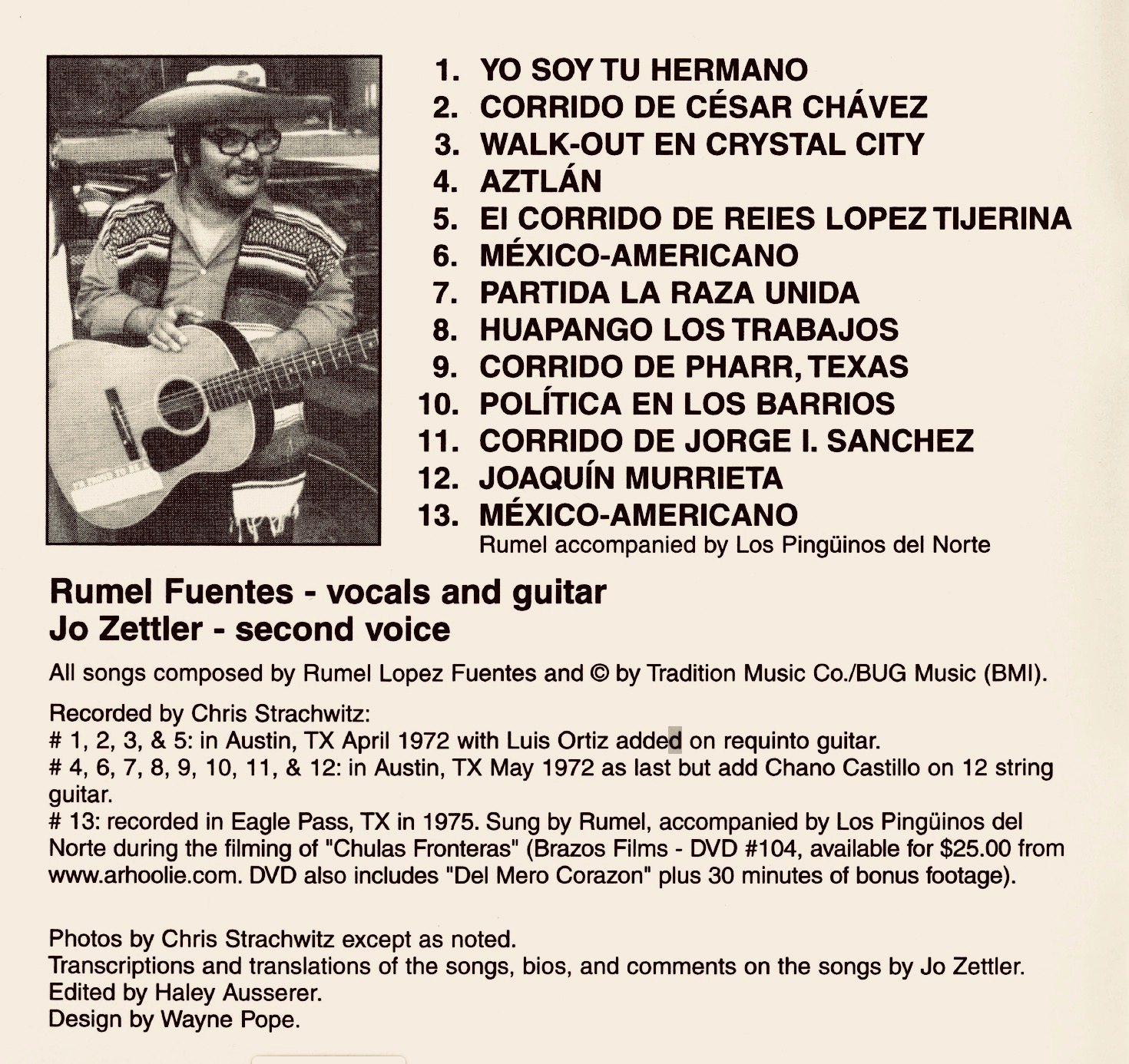

Fuentes began writing his own corridos, singing about the Chicano Movement and its heroes as well as the everyday life of Mexican Americans in the United States. He wrote about rebels from different centuries (Joaquín Murietta and Reies Lopez Tijerina) as well as admired leaders of La Causa (“Corrido de Cesar Chavez”). His songs explored the themes of brotherhood or carnalismo (“Yo Soy Tu Hermano”), police brutality (*Corrido de Pharr, Texas”), the struggle for better schools (“Walk-Out en Crystal City”), the travails of migrant workers (“Huapango Los Trabajos”), and the proud assertion of a new identity (“Méxicoamericano”).

Fuentes began writing his own corridos, singing about the Chicano Movement and its heroes as well as the everyday life of Mexican Americans in the United States. He wrote about rebels from different centuries (Joaquín Murietta and Reies Lopez Tijerina) as well as admired leaders of La Causa (“Corrido de Cesar Chavez”). His songs explored the themes of brotherhood or carnalismo (“Yo Soy Tu Hermano”), police brutality (*Corrido de Pharr, Texas”), the struggle for better schools (“Walk-Out en Crystal City”), the travails of migrant workers (“Huapango Los Trabajos”), and the proud assertion of a new identity (“Méxicoamericano”).

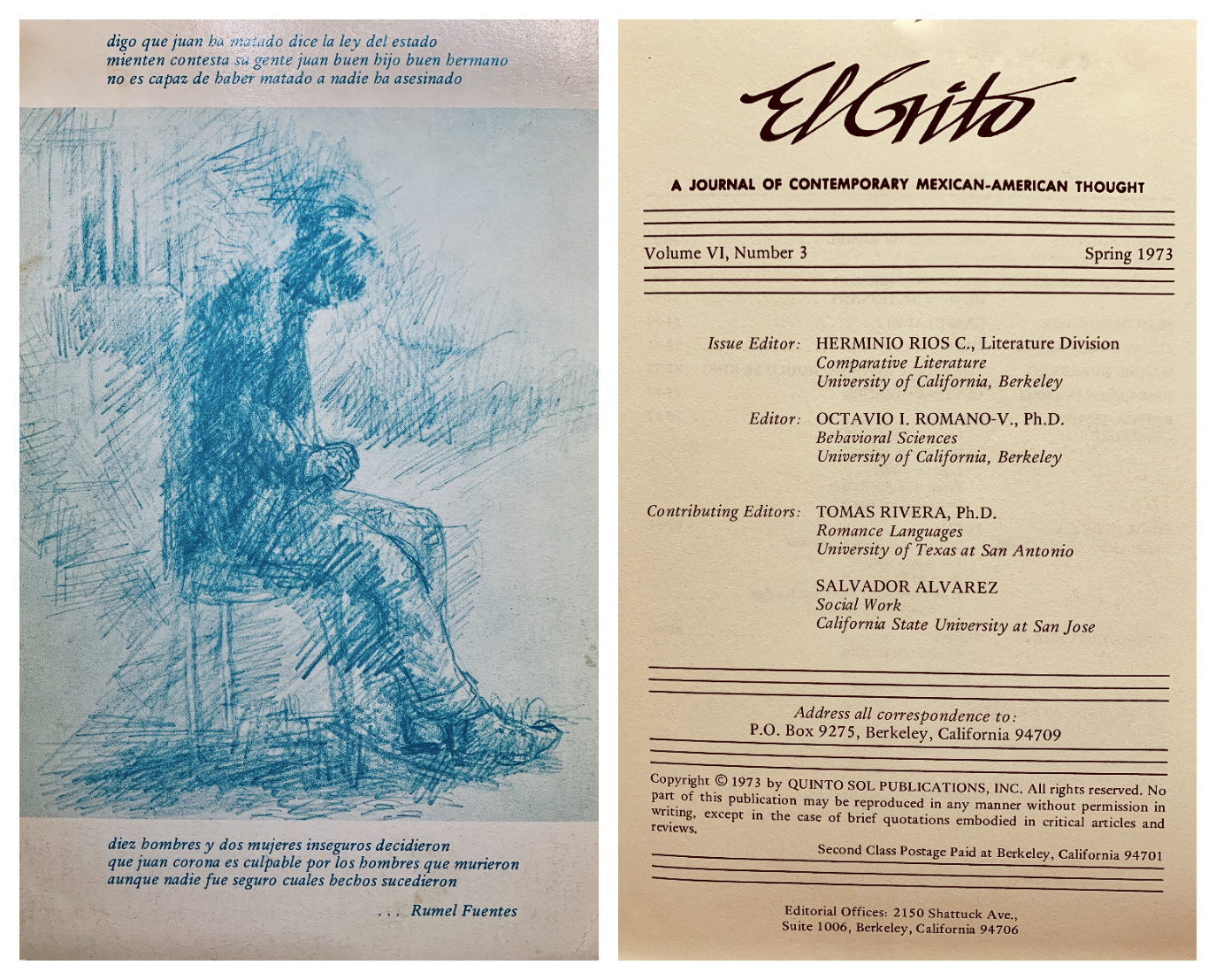

One of the songs that especially touched me tells the tale of serial killer Juan Corona, convicted of killing 25 men near Sacramento. I covered the trial in 1972 for my Chicano newspaper at UC Berkeley, in a cover story we called “The Trial of a Family.” It focused on the emotional and financial havoc the notorious case had taken on Corona’s family, who believed in his innocence. His wife and four daughters attended the trial daily, dressed in their Sunday best. His brothers travelled up and down the state raising money and awareness for their brother’s defense.

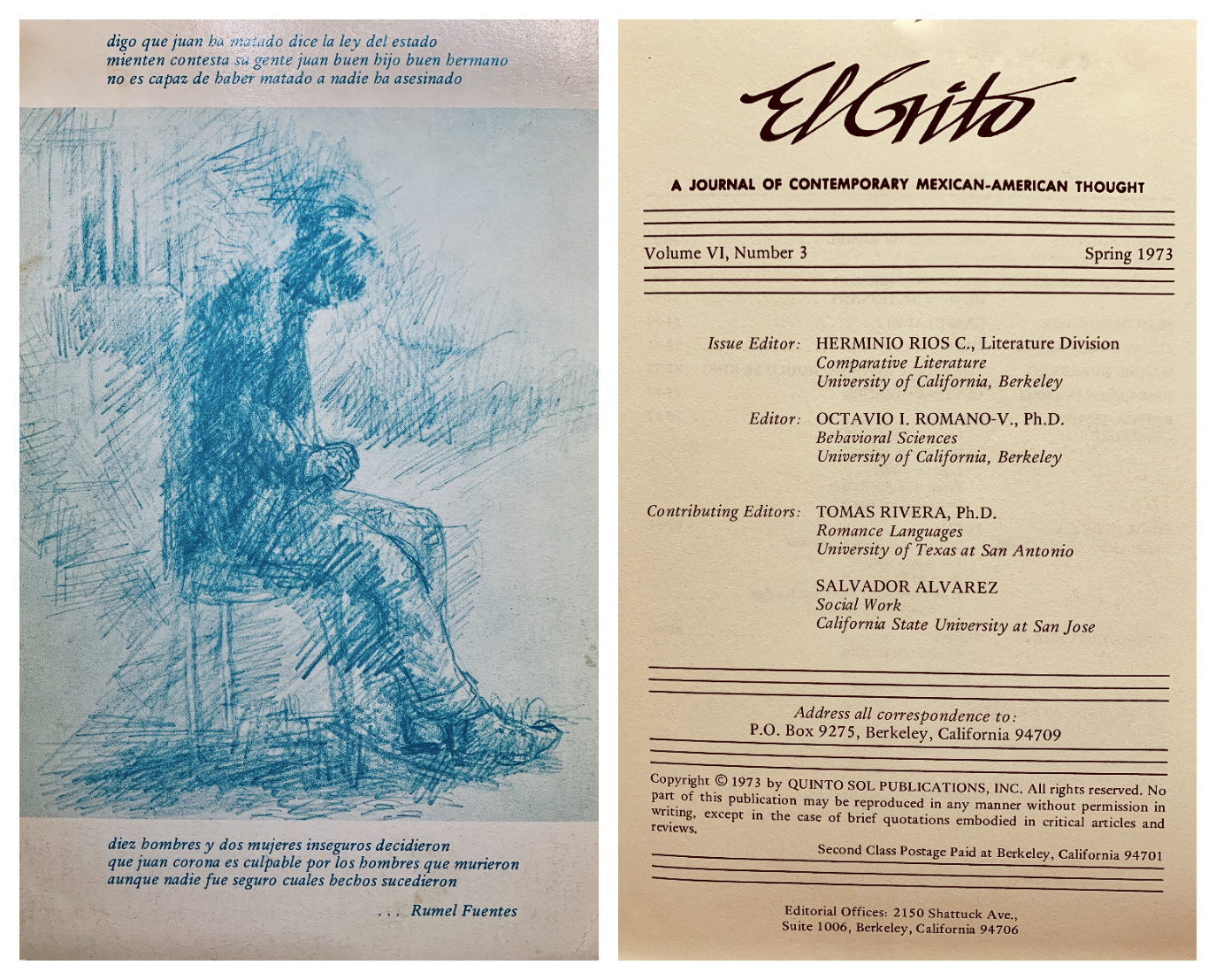

Fuentes’s song, “Corrido de la Familia de Juan Corona,” expresses a sense of outrage about the justice system, citing the inept prosecution and corrupt defense in this case. It’s an outrage that was shared by Chicano activists, including the Brown Berets who demonstrated outside the courthouse in their paramilitary uniforms. Fuentes’s sorrowful lyrics – written in a newspaper style typical of corridos – are featured with a ghostly illustration on the cover of EL Grito, the pioneering Chicano journal based at UC Berkeley.

Fuentes’s song, “Corrido de la Familia de Juan Corona,” expresses a sense of outrage about the justice system, citing the inept prosecution and corrupt defense in this case. It’s an outrage that was shared by Chicano activists, including the Brown Berets who demonstrated outside the courthouse in their paramilitary uniforms. Fuentes’s sorrowful lyrics – written in a newspaper style typical of corridos – are featured with a ghostly illustration on the cover of EL Grito, the pioneering Chicano journal based at UC Berkeley.

“Digo que Juan ha matado,” dice la ley del estado.

“Mienten!” contesta su gente. Juan, buen hijo, buen hermano,

No es capaz de haber matado. A nadie ha asesinado.

Diez hombres y dos mujeres inseguros decidieron

Que Juan Corona es culpable por los hombres que murieron,

Aunque nadie fue seguro cuales hechos sucedieron.

The Fuentes corridos gave voice to a community often called a “sleeping giant” for its political passivity despite its increasingly weighty demographic. He performed them enthusiastically with a small backing trio of guitars and vocals, appearing at political rallies, voter registration drives, and other grassroots venues up and down the state.

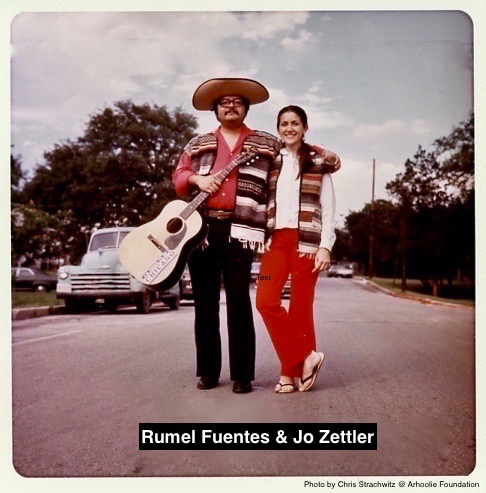

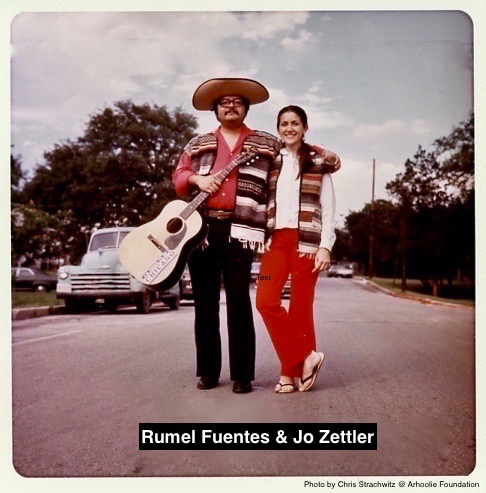

In 1967, Fuentes met his future wife, Jo Zettler, another activist who came to Eagle Pass as a VISTA Volunteer. They became soul mates through their shared politics and passion for performing.

“I learned to speak Spanish and was very involved in community organizing there,” writes Zettler in the notes to the CD. “Even though I was not Mexican American, I loved the people I worked with and deeply admired their culture, particularly the way music was a part of their lives. I had been singing harmony all my life and singing traditional Mexican music (and dancing to it!) brought Rumel and me together.”

The couple married in 1968. Zettler ran a Planned Parenthood clinic while Rumel earned his A.A. degree, trekking by bus to a junior college 60 miles away. The couple then moved to Austin so he could attend the University of Texas. Fuentes received a Master’s in Education in 1974, then settled down to teach elementary school in his hometown.

While attending the university, Fuentes and his wife both joined El Teatro Chicano de Austin, an improvisational troupe that presented skits, or actos, patterned after the legendary Teatro Campesino founded by playwright Luis Valdez of Zoot Suit fame. Fuentes is credited as a driving force behind the group, which performed in 1971 at the Smithsonian Institution’s Festival of American Folklife, held over five days on the National Mall in Washington, D.C.

While attending the university, Fuentes and his wife both joined El Teatro Chicano de Austin, an improvisational troupe that presented skits, or actos, patterned after the legendary Teatro Campesino founded by playwright Luis Valdez of Zoot Suit fame. Fuentes is credited as a driving force behind the group, which performed in 1971 at the Smithsonian Institution’s Festival of American Folklife, held over five days on the National Mall in Washington, D.C.

El Teatro Chicano soon became influential within the Chicano Movement in Texas, and served as a platform for the live performance of Rumel’s songs.

“I see the corrido as a means of exposing evils and injustices and relating the truth about things as they actually happen,” Fuentes wrote in an introduction to “Corridos de Rumel,” a compendium of his compositions which appeared, complete with sheet music, in El Grito’s, Spring 1973 issue. “It is sort of an ‘emotional escape valve.’ The modern corrido, especially the Chicano corrido, is the kind of song that turns your stomach with hatred or fills your heart with pride, gladness and hope.”

It took time, however, for Fuentes to come around to that appreciation. As a child, he admits he “neither understood nor liked the corrido,” although his father’s silent passion for the music made an indelible impression on the boy, since the time he was six.

“He would stop doing whatever he was doing, or stop as he was walking by the radio, walk up to it, and listen to the complete corrido, then walk off without a single comment,” Fuentes recalls. “He was a quiet man, but I could see an expression on his face that was one of pleasure and pride.”

Thus, the cultural seed was planted, waiting to develop.

Meanwhile, Fuentes says he succumbed to the “acculturation process” in the public schools of Eagle Pass, which he calls “brain-washing.” He became a “rock-and-roller” who dismissed Mexican music as “low class” in favor of “nice, good American Music.”

His eventual reawakening would parallel the evolution of the Chicano Movement, which encouraged the search for cultural roots and elevated pride to displace the disparagement of Anglo society. That’s when he finally understood the relevance of those old corridos his father used to sing.

“It was here that I saw the spark I had been looking for: not all Mexicans are lazy, dumb, and passive, as I was being led to believe,” Fuentes wrote. “At this moment, I realized that what the Gringo implied and said was not true. My father had escaped this mass brainwashing of Chicanos. He never watched TV or went to school. He lived the things in the corridos.”

Fuentes attended UT Austin at a time when serious scholarship about the corrido was being developed there by a renowned figure in the field of folklore, Américo Paredes (1915-1999), who founded the university’s Center for Mexican American Studies. The scholar’s archives – Américo Paredes Papers, 1886-1999, part of the university’s Benson Latin American Collection – include two rare singles recorded by Fuentes at the time. They include “Soy Chicano” backed by “Corrido de Cesar Chavez,” released in 1975 on Arhoolie Records. And of special interest, “Mexicano-Americano” with “Yo Soy Tu Hermano” on Aztlan Records of Eagle Pass, the artist’s vanity label, featuring Fuentes and his wife billed as Rumel y Jo con Teatro Chicano.

Paredes, who was a musician himself, would have likely had a powerful impact on the young artist-activist. Yet, Fuentes credits his father as his main inspiration.

“I began paying more attention to the corridos my father sang and played with his guitar,” he states. “It could have been the feeling my father put into the corrido, but this time, I heard the full meaning. It is (the story of) a suffering, quiet man who never complains nor says much for years, then all of a sudden this quiet man stands up and with a melodious, clear voice tells you exactly what life is all about.”

Like the historic corridistas before him, Fuentes wrote about the world around him, from small-town tragedies to epic social struggles. And keeping with corrido tradition, his songs often feature the anonymous everyman who undertakes a heroic battle to defend his dignity, assert his identity, and stand up for his rights, against daunting odds.

“The corridos usually consist of happenings that are true but that for some reason never did hit the newspapers,” Fuentes writes. “These corridos also have something to do with the eternal fight between the haves and the have-nots …. In many cases, heroes of the corrido pay for their ‘impudence’ or ‘rebelliousness’ with their lives, preferring death before injustice.”

While hewing to tradition, Fuentes also brought a different approach to his corridos, in both content and context.

“The style of my corridos is in some ways very new,” he states. “Rather than hearing them around campfires and "troop trains" and in cantinas, you hear them around conferences, political rallies, huelgas, and sometimes wherever Chicanos gather to talk and drink beer.”

He also cited a distinction that reflects a sense of futility, a sharp contrast to his fighting spirit and sense of purpose.

“In my corridos, most of the fights and the killings are very uneven ones,” he said. “It is harder to fight back now. Before, it was man to man, and now it is man against efficient organizations.”

The True Meaning of Corridos

In El Grito, Rumel wrote a brief description of each song, attempting to explain his reasons for writing them. He cautioned, however, that “the real meaning” cannot be conveyed in words alone.

“The meaning will be in a corrido singer who trembles as he sings and the acknowledgement of understanding by a big smile and a loud grito (from) the listener,” he states. “It is here that the deep secret of the corrido is sung, and only true Chicanos will understand it fully and completely and get the true meaning not found in books.”

Luckily, there was one non-Chicano who would prove him wrong. His name is Chris Strachwitz and he got the true meaning of the corrido the instant he heard a live performance, though he didn’t understand the Spanish lyrics.

The record collector and producer had heard Mexican music on the radio as he traversed the South in search of blues and other grassroots artists to record. He wanted to work with Mexican musicians as well, but he would need help in navigating a culture that was foreign to him. Strachwitz consulted with Jerry Abrams, a young lawyer working with the UFW in the Rio Grande Valley, who in turn led him to this friendly English-speaking artist living on the border.

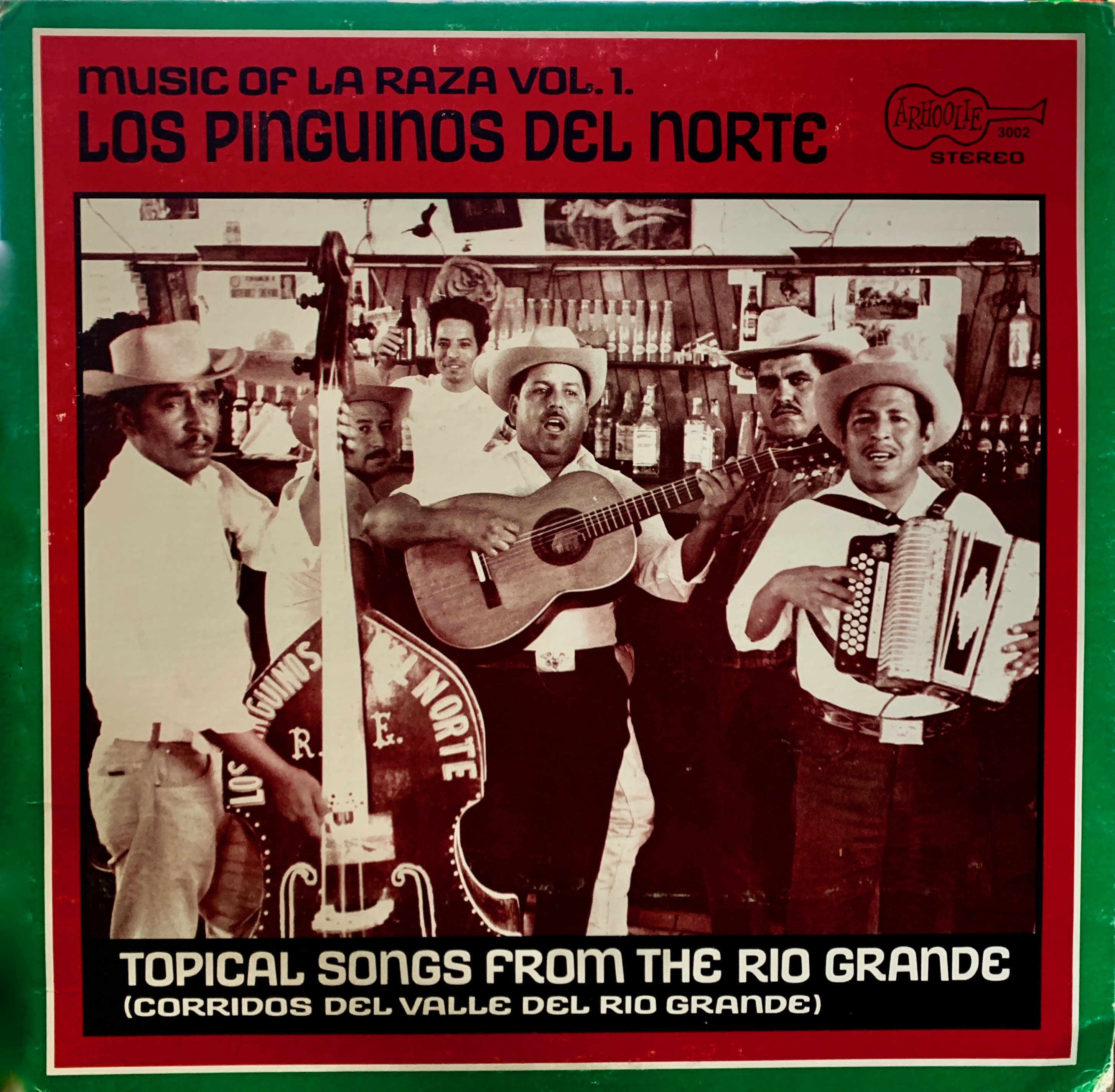

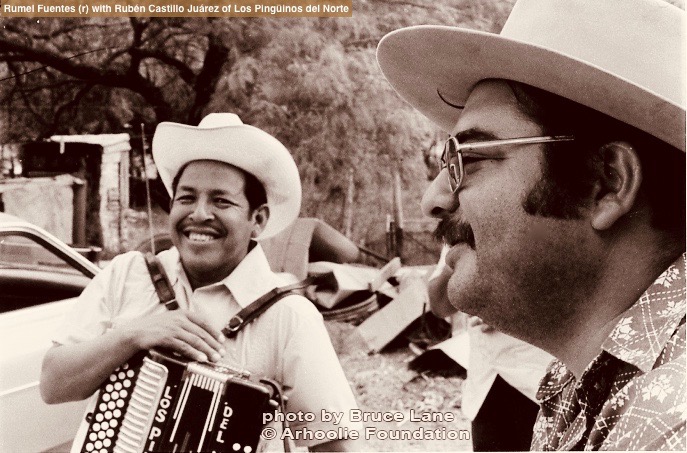

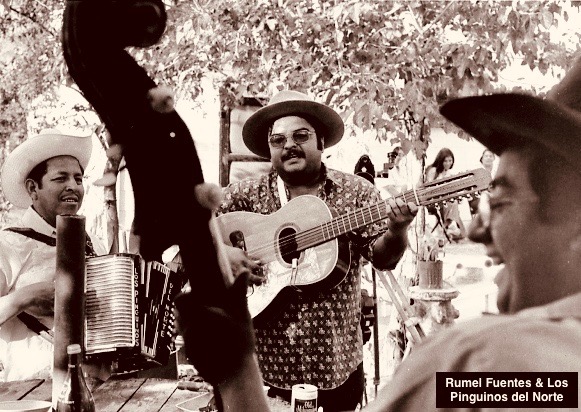

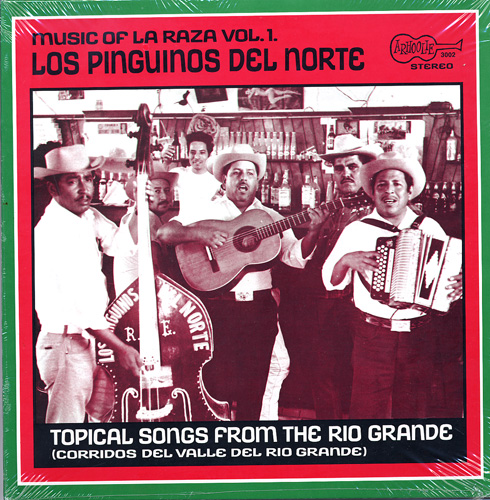

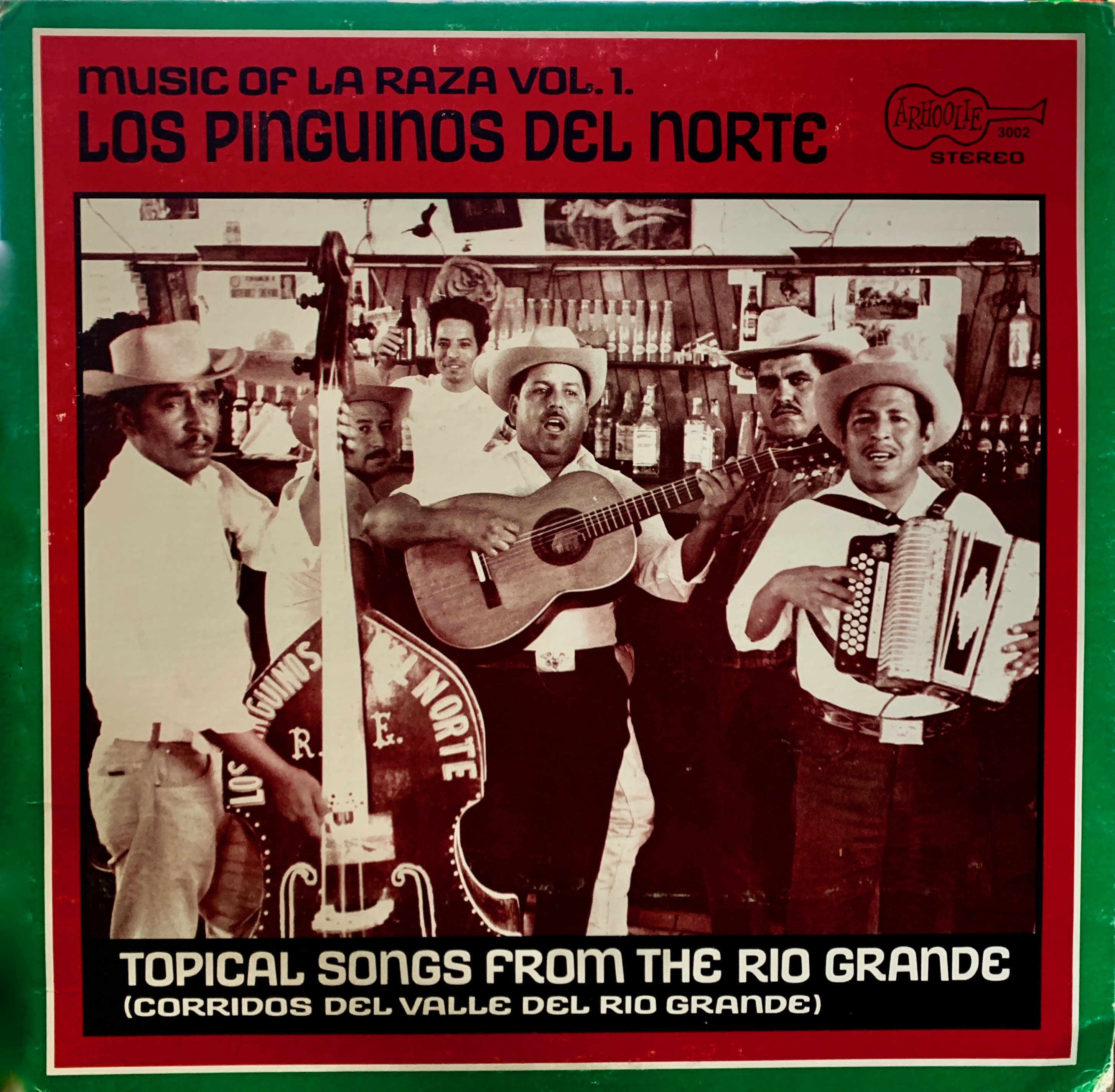

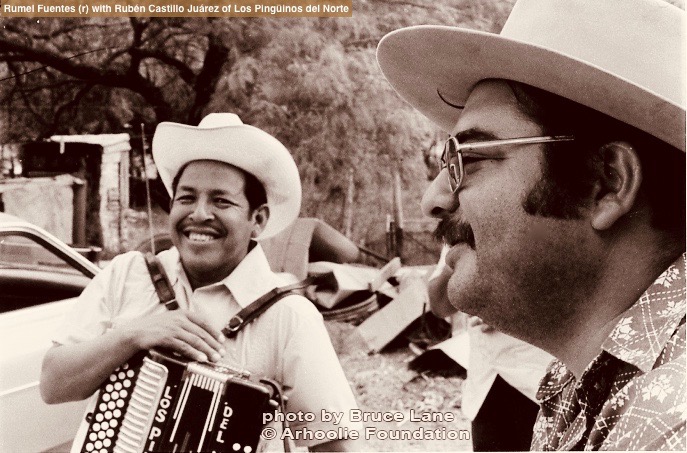

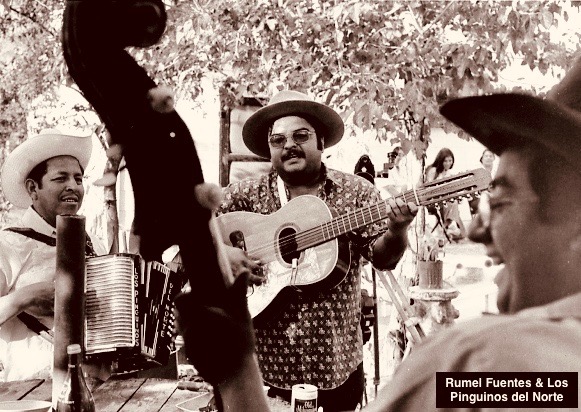

In 1970, Strachwitz made his way to Eagle Pass to make contact with Fuentes, who happily agreed to serve as his guide to the other side. That partnership led to the first of many Mexican music recordings issued by Arhoolie Records. It was titled Music of La Raza Vol. 1: Topical Songs from the Rio Grande Valley by Los Pinguinos del Norte, recorded live on May 7, 1970, at El Patio, a cantina on the Mexican side of the border.

“When Rumel took me to this little bar (next to El Patio) in Piedras Negras, I was just totally knocked out by the Pinguinos,” recalled Strachwitz in an audio interview recorded in June and posted to the Arhoolie website. “I thought this was just wonderful. Especially the way the people reacted in that bar. They would shout gritos. They would cry out when it would hit them. I was really impressed as to how emotional the songs were to people. Although the emotions were not expressed by the musicians themselves; they sang with total straight face, and no comments from them at all. It was the audience that would react.”

Fuentes, who is credited as co-producer on the inaugural album – later released on CD under the title “Corridos De La Frontera” – also sang on one track, his own composition “Mexico Americano.” (Note: the spelling of the title varies depending on the source.) Later, Fuentes and Los Pinguinos would appear briefly in the acclaimed music documentary Chulas Fronteras (1976), produced by Strachwitz and directed by Les Blank. (In 1993, the film was named to the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress, qualifying as "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.”)

Fuentes, who is credited as co-producer on the inaugural album – later released on CD under the title “Corridos De La Frontera” – also sang on one track, his own composition “Mexico Americano.” (Note: the spelling of the title varies depending on the source.) Later, Fuentes and Los Pinguinos would appear briefly in the acclaimed music documentary Chulas Fronteras (1976), produced by Strachwitz and directed by Les Blank. (In 1993, the film was named to the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress, qualifying as "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.”)

Strachwitz also made home recordings of Fuentes over two sessions in April and May of 1972, in the Austin apartment the singer shared with his wife. They were cramped quarters, as Zettler recalls, with “a student photographer, two musicians, and Rumel and I all crowded into our tiny living room in married student housing.”

Looking back, Strachwitz regrets not releasing those recordings much sooner. He had worried there was no market for political songs by an artist who was relatively unknown beyond his home turf. The recordings gathered dust on a shelf for almost four decades.

Meanwhile, the artist died of liver disease in 1986, at the age of 43. The album of his songs would not appear for another 23 years. In the interim, other artists honored his legacy with renditions of his most beloved song, the one he first recorded in that cantina with Los Pinguinos, “Mexico Americano.” After the composer’s death, the corrido was covered live by Los Lobos (1999), and later included in the acclaimed band’s album, Acústico en Vivo (2005). It was also recorded by Alejandro Escovedo for the play By the Hand of the Father (2002). A different Fuentes tune, “Yo Soy Tu Hermano, Yo Soy Chicano,” appeared in a compilation CD entitled Rolas de Aztlán: Songs of the Chicano Movement (2005).

After Arhoolie released Fuentes’s posthumous album in 2009, interest in the artist intensified. Additional covers of “Mexicano Americano” were recorded by La Santa Cecilia (2017) and Los Texmaniacs (2018), and the song was performed live by Los Cenzontles (2019) at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C.

These recordings by a new generation show that the music of Rumel Fuentes gained renewed relevance in the age of anti-immigrant sentiment and racial discord.

“As the political climate has shifted and Americans of Hispanic origin have been demonized and victimized from the top to the bottom of the new Republican Party and its media arm, Fox News, ‘México-Americano’ has taken on new meaning,” wrote blogger Ed Maxin in his 2019 article, “The Fraught Journey of ‘México-Americano.’ ”

In life, Fuentes was deeply disappointed by the failure to see his body of recorded songs released to the public. It was a goal he had long aspired to.

“I hope to someday do an LP recording of some of this material,” Fuentes wrote in the 1973 journal article. “Much work has gone into writing these corridos and I hope that they may accomplish their purpose, someday.”

Fuentes and his wife were divorced in 1975, three years after making those home recordings on which she sang harmony. Zettler moved to the West Coast to pursue a graduate degree, and settled in Portland, Oregon. The two rarely spoke after their split. Yet for Zettler, the release of her husband’s CD after so many years revived memories of their time together, making music and fighting the good fight.

Zettler, in fact, contributed to the album’s liner notes, providing insightful descriptions of each song. And in that newspaper interview when the album was finally released, Zettler reflected affectionately on her ex-husband and his work.

She recalls a gentle soul inside the political firebrand.

"Things that happened back then to people because they were Mexican Americans, he could get very passionate, very angry about it," Zettler said. "But he wasn't a rabble-rouser. He wasn't one of the guys that stirred people up.

“He mostly went out and sang."

– Agustín Gurza

Blog Category

Tags

Images