“Allá en el Rancho Grande:” The Song, the Movie, and the Dawn of the Golden Age of Mexican Cinema

Almost every country has a set of songs that make up its musical DNA. Songs that children learn almost from the time they can speak, such as “Home On the Range,” “Oh, Susana,” and “This Land Is Your Land” in the United States.

Almost every country has a set of songs that make up its musical DNA. Songs that children learn almost from the time they can speak, such as “Home On the Range,” “Oh, Susana,” and “This Land Is Your Land” in the United States.

In Mexico, one such iconic tune is the ranchera classic “Allá en el Rancho Grande.” Like other songs emblematic of a national culture, “Rancho Grande” has a melody that is instantly recognizable and a lyric that seems to spring from the country’s collective memory, though we may not understand exactly what the words mean.

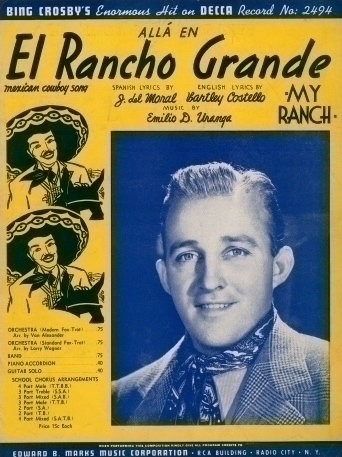

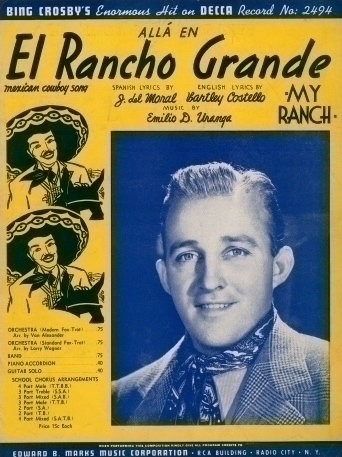

This merry mariachi ditty became so popular, so entwined with Mexican identity, that even outsiders became familiar with the composition and the charro (cowboy) culture it stood for. In the United States, it was re-titled “Out on the Big Ranch,” picking up English verses and a catalog of recordings by everybody from Bing Crosby to Elvis Presley.

More on the Americanization of the renowned ranchera in a moment. First, a little history about the song that became a cornerstone of Mexican pop culture in the 20th century.

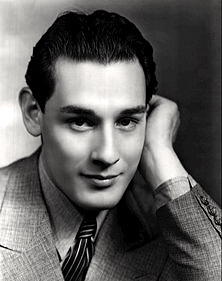

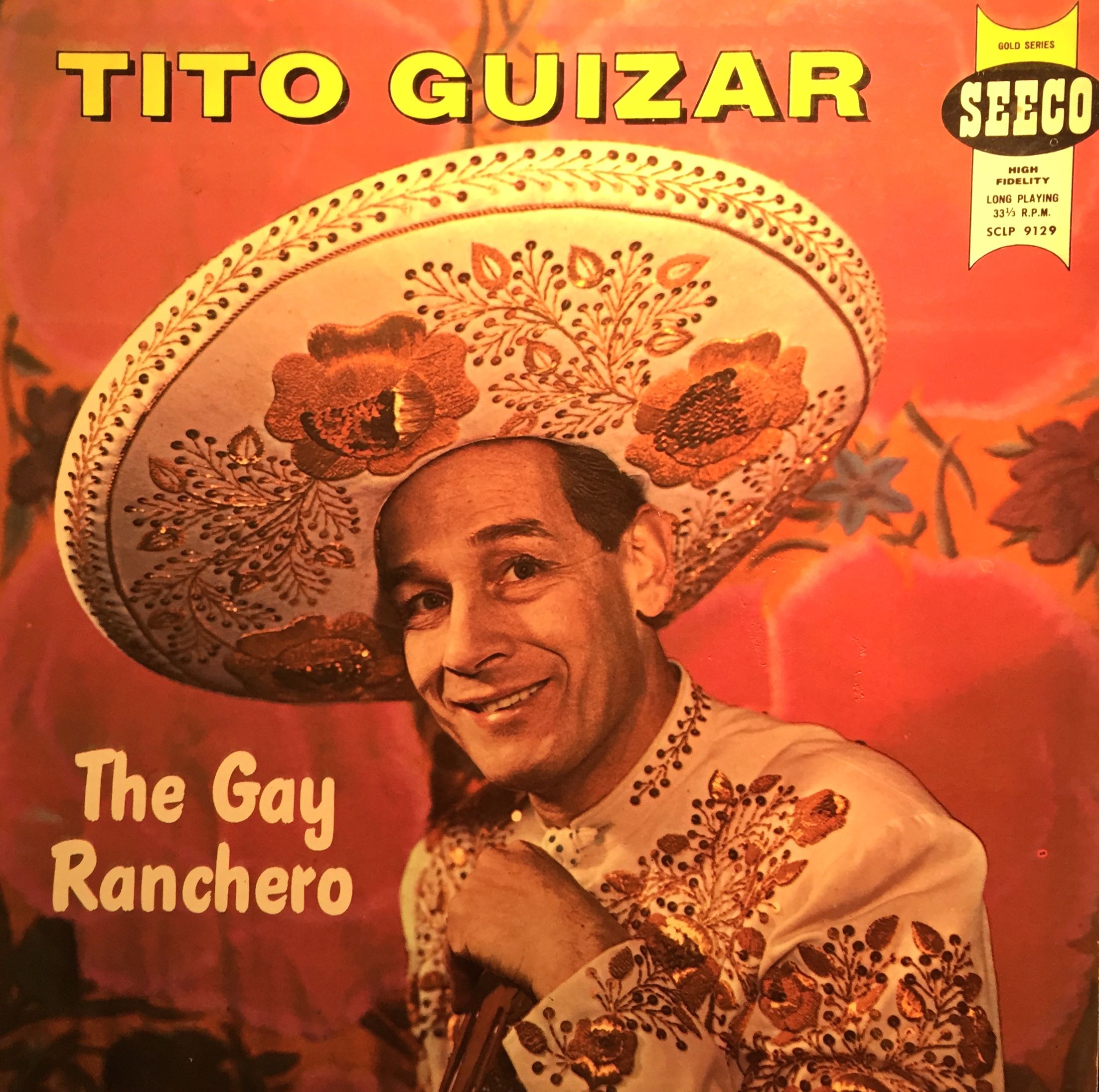

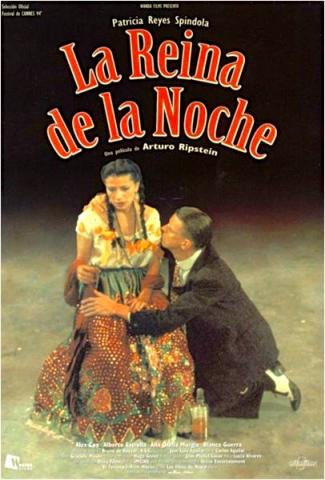

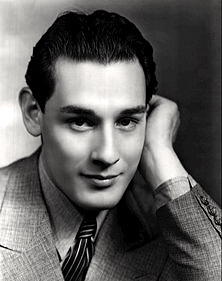

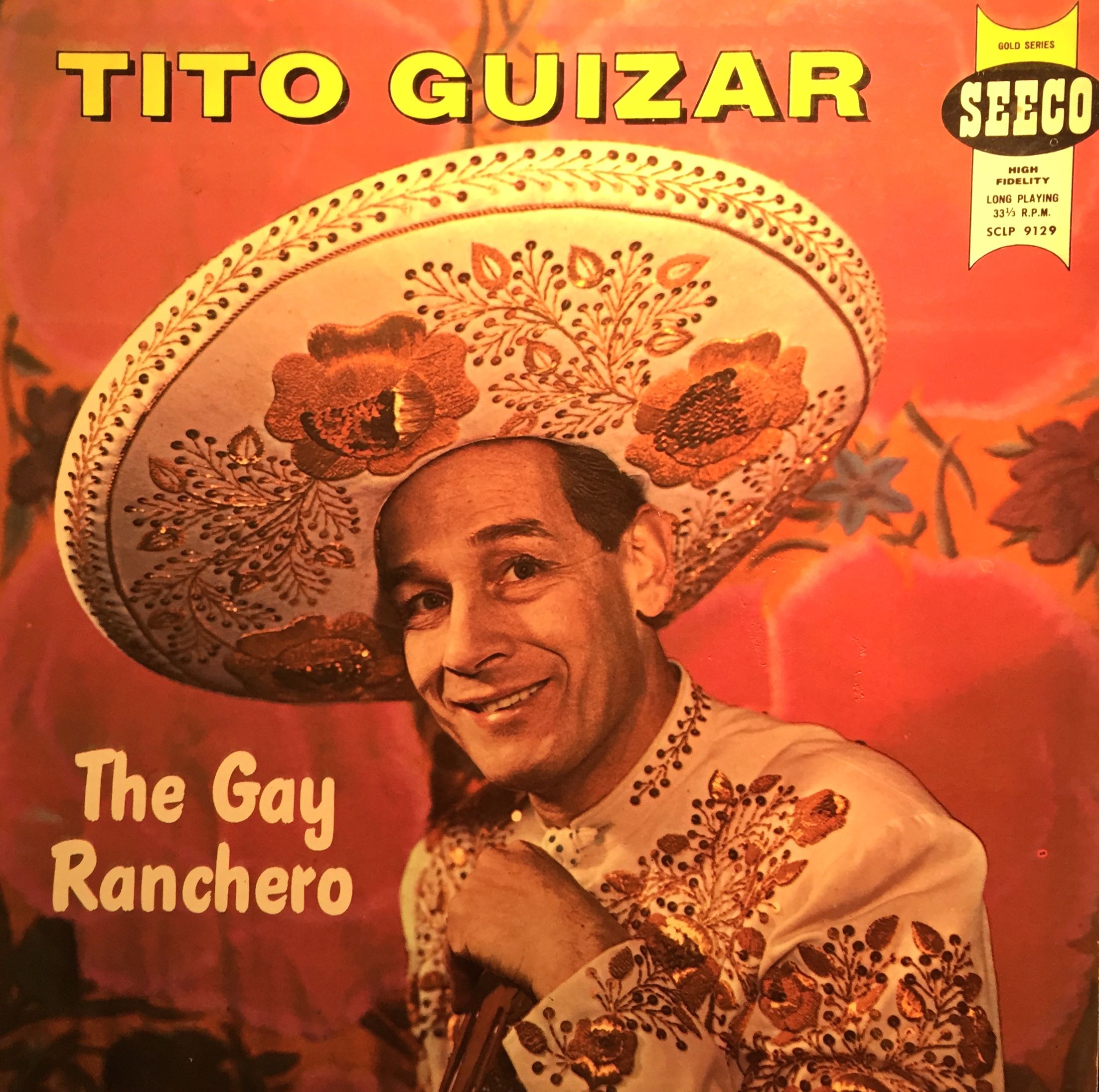

“Allá en el Rancho Grande” first gained popularity in 1936 via a historic Mexican film of the same name, starring singer and actor Tito Guízar. The film is seen as a milestone in Mexican cinema, ushering in the so-called “Golden Age” of movies that would define Mexican national identity for a generation.

“Allá en el Rancho Grande, was the film that found the formula for commercial success capable of converting Mexican cinema into a true industry,” states a film history source often quoted on cultural websites. “The film captivated the public in all the Spanish-speaking countries, and opened the doors for the flood of films that would come to consolidate the Golden Age.”

The movie was directed by Fernando De Fuentes, who had received critical acclaim for an earlier film, Vámonos con Pancho Villa(1935). Though not admired by critics, Rancho Grande was by far more successful at the box office. It became the first Mexican movie to be released in the Unites States with English subtitles, according to the film history. It also became Mexico’s first film to win international recognition, with a special recommendation for the cinematography of Gabriel Figueroa at the 6th Venice International Film Festival. (Some websites claim the film won the festival’s award for cinematography, but the movie itself was not included in the official competition that year, which saw Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs win a special Grand Art Trophy.)

Critics claim the film is corny and even reactionary given its idyllic, rose-colored depiction of feudal hacienda life, which had sparked the Mexican Revolution 25 years earlier. Yet, it set the standard for what would be the most popular film genre of the era in Mexico, the comedia ranchera. It gave filmmakers the formula for making hit movies: A glorification of Mexico’s rich folkloric roots, not only in music but in its traditional lifestyle and colorful local characters.

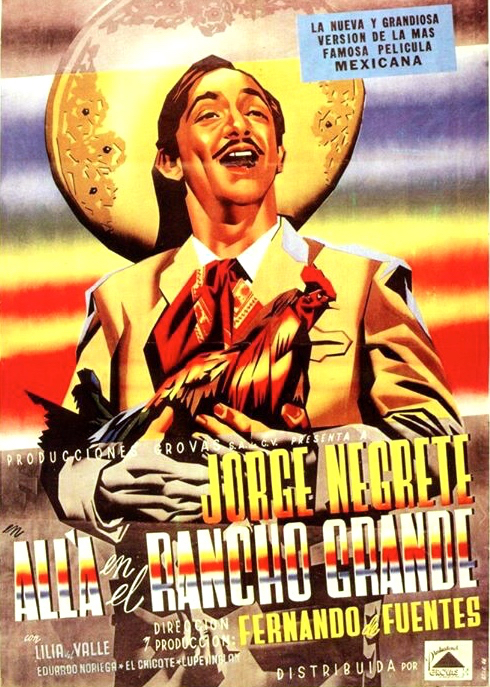

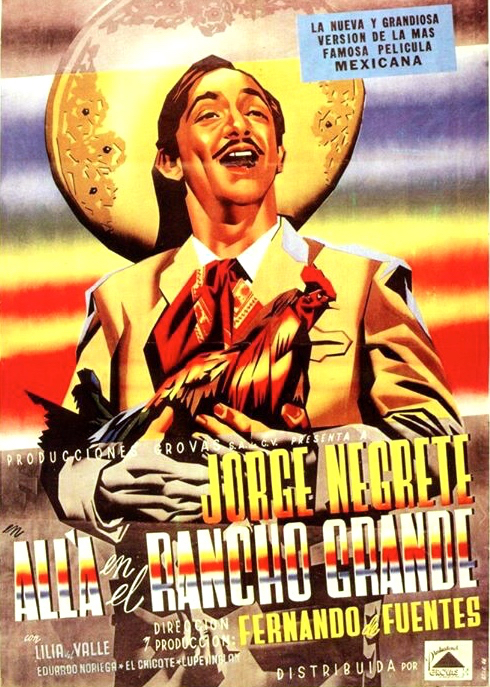

Rancho Grande – which was remade by the same director in a 1949 version starring Jorge Negrete – is the humorous story about a love triangle set on a ranch. The movie is replete with comic misunderstandings as two men – the hacendado, or ranch owner,and the ranch manager, played by Guízar – compete for the romantic attention of the same woman, played by Esther Fernández. (Ten years later, she starred with Brian Donlevy and Alan Ladd in Two Years Before the Mast.)

The original “Rancho Grande,” wrote my friend and colleague Enrique Lopetegui, “has all the things you would expect from charro cinema: men, wine, music, guns, and women. Yet you can’t keep your eyes off the screen. The movie’s look (courtesy of Figueroa) and musical importance are undeniable.”

The musical significance can’t be overstated: From that point forward, Mexican movies and popular song would be inextricably linked. That is why Mexican singers were often also the stars in the ranchera films of the Golden Age. Tito Guízar, for example, would go on to Hollywood where he co-starred with U.S. celebrities such as Roy Rogers, Mae West, and Dorothy Lamour. And he became closely identified with other Mexican folk music classics known throughout the world, such as “Cielito Lindo” and “La Cucaracha.”

“The image of the singing charro, the emblem of Mexican virility, was at one level clearly a reworking of Roy Rogers and Gene Autry films,” writes John King in his 1990 book Magical Reels: A History of Cinema in Latin America. “But the film is more complex than a mere imitation of Hollywood’s singing cowboys. It drew on established popular culture, the canción ranchera, and helped to transform this song form into part of a very successful culture industry… Song became an essential part of national cinema, the sentimental underpinning which linked scenes together, and gave greater weight to specific situations.”

As with many traditional songs, there has been a vigorous debate about who actually wrote “Allá en el Rancho Grande.” Some say nobody can take credit for the composition because the authorship is unknown, a theory briefly described on the blog, MúsicaPara Nostáligcos. The tune was around long before it had any commercial success, the argument goes, and is simply a folk song that’s now public domain.

Nevertheless, prominent songwriters on both sides of the border have claimed copyrights for “Allá en el Rancho Grande.” At one point, the dispute actually wound up in court.

The most widely accepted credit is by Juan Díaz del Moral, for the lyrics, and Emilio Donato Uranga, for music. The song was originally written for Mexico City’s vibrant musical theater, according to Diaz del Moral’s biography on the website of SACM, the Mexican composer’s society. The pair reportedly registered the song in 1927, nine years before the film was released.

The most widely accepted credit is by Juan Díaz del Moral, for the lyrics, and Emilio Donato Uranga, for music. The song was originally written for Mexico City’s vibrant musical theater, according to Diaz del Moral’s biography on the website of SACM, the Mexican composer’s society. The pair reportedly registered the song in 1927, nine years before the film was released.

In the United Sates, however, the song was registered a year earlier by Silvano Ramos, with English lyrics by Bartley Costello. This is the version performed in 1940 by popular cowboy singer Gene Autry, featuring violins, twangy guitar, and Costello’s country-loving verses:

Give me my ranch and my cattle,

Far from the great city’s rattle.

Give me a big herd to battle,

For I just love herding cattle.

In the early 1940s, Ramos’s representatives sued to defend his claim to the song. The suit, filed in New York, did not challenge the competing copyright in Mexico. Instead, Ramos’s publisher sued the authors of a book claiming that “Rancho Grande” belonged in the public domain because it was a “Mexican song that had been sung in the southwest since time immemorial.” That publication – American Ballads and Folk Songs, published by The Macmillan Company in 1934 – was written by highly respected folklore experts John andAlan Lomax.

The judge couldn’t decide the case definitively for lack of sufficient documentation. But he did turn down Ramos’s petition for summary judgment, saying the issues should be settled at trial, although it’s not clear if a trial was ever held. A summary of the 1941 decision can be found here, at a website on music copyright infringement sponsored by the law schools at Colombia Universityand USC.

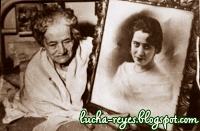

There is no dispute, however, about who wrote the original story that led to the making of the movie. And that happens to lead us back to my hometown of Torreón, in the northern state of Coahuila. Torreón was also the home of Luz Guzman Aguilera de Arellano, the educator and mother of five children who originally called her story “Cruz” for the passionately pursued female protagonist. According to an article in El Siglo de Torreon, the author, nicknamed Lucita, based the work on a true story that had taken place on a hacienda in neighboring Chihuahua state.

Lucita, the newspaper recounts, secretly wrote the story longhand in a notebook that she stashed away in a dresser. Later, when the family discovered the notebook and read the story, they were moved to tears, according to Lucita’s surviving children.

The story made it to the screen thanks to Lucita’s brother,Antonio Guzmán Aguilera, a writer, poet and composer known by the stage name Guz Aguila. He adapted the story and submitted the screenplay to director De Fuentes. Both Aguila and his sister Lucita are credited as writers for the film, along with the director, who shares screenplay credit.

Lucita was happy with her newfound success, even though she was paid only $500, which she used to buy a dress, her children recall. The only thing that bothered her was that the filmmakersmodified her true-to-life account.

“My mother was very excited, except that they changed the ending on her,” states the author’s daughter Luz Arellano. “In her novel, Cruz dies at the end, but not in the movie because my uncle (Guz Aguila) told her the public wasn’t ready for that. They needed a happy ending.”

Lucita was very angry about the changes, the daughter added, until she realized how much money the movie was making, and that cheered her up.

Although the movie’s storyline may be simple, the Spanish song lyrics, unlike the English, can be a little inscrutable. Take, for example, the song’s famous opening verse:

Allá en el rancho grande, allá donde vivía,

Había una rancherita, que alegre me decía,

Que alegre me decía:

“Te voy a hacer tus calzones, como los que usa el ranchero.

Te los comienzo de lana, Te los acabo de cuero.”

The song is narrated by a man who talks about a little country girl who was out on the big ranch, “where I used to live,” and who used to say to him, “I’m going to make your breeches like the ones rancheros wear. I’ll start them for you in wool, and finish them for you in leather.”

Now, the word calzones leaves the story open to interpretation. Considering the time the song was written, it could mean long-johns. But it also could mean underwear. In any case, there’s a suggestive undertone.

Now, compare the wholesome, straightforward lyrics in English, like those sung by 1950s crooner Dean Martin:

I love to roam out yonder, out where the buffalo wander.

Free as the eagle flying, I'm a-roping and a-tying.

I'm a-roping and a-tying.

The Dean Martin rendition has an upbeat, quasi-salsa arrangement that clashes with the tune’s country spirit. But that is also an example of the adaptability of the song, which has been rendered in a number of styles, from Tommy Dorsey’s twangy Dixieland mélange to Elvis Presley’s frenetic Las Vegas number. And then there’s my favorite bicultural version, the spirited, countrified and amazingly authentic performance by father-son act Bill and Roger Creager, filmed in 2013 at The County Line Music Series in San Antonio.

The Dean Martin rendition has an upbeat, quasi-salsa arrangement that clashes with the tune’s country spirit. But that is also an example of the adaptability of the song, which has been rendered in a number of styles, from Tommy Dorsey’s twangy Dixieland mélange to Elvis Presley’s frenetic Las Vegas number. And then there’s my favorite bicultural version, the spirited, countrified and amazingly authentic performance by father-son act Bill and Roger Creager, filmed in 2013 at The County Line Music Series in San Antonio.

The Frontera Collection contains a wide variety of recordings of the classic song, starting with the Tito Guízar original on RCA Victor. The credits on that 78-rpm recording indicates Guízar did the arrangement, with guitar accompaniment. Interestingly, though, the label has no songwriter credits.

The following is a selection of 10 recordings from the Frontera Collection, reflecting the wide variety of styles to which the song was adapted.

“El Rancho Grande” by Mariachi Miguel Diaz (Audio Fidelity AF-1816)

A lively instrumental version by this famed mariachi on a U.S. label.

“Allá En El Rancho Grande” by Pilar Arcos y Juan Pulido (Vocalion A 8114)

An old-timey rendition by this popular duet accompanied by orquesta típica, with comical gritos thrown in for good measure.

“Rancho Grande” by Beto Villa y Su Orquesta (Ideal 655-B)

Another instrumental, this time in a playful Tex-Mex arrangement with a

cool clarinet solo.

“El Rancho Grande” by Paulino Bernal (Bernal BE-103)

This Tex-Mex version by the respected Conjunto Bernal opens with the bass playing the famous melody, punctuated by other instrumental flourishes and interesting time changes.

“I Love My Rancho Grande” by Freddy Fender (Crazy Cajun CC-2014)

This raucous, beer-joint rendition has that trademark Freddy Fender sound, featuring accordion embellishments running throughout. The label gives songwriting credits to Fender, under his real name of Baldemar Huerta, though he sings the standard Spanish lyrics and didn’t even bother to add English verses of his own.

“En El Rancho Grande” by Cuarteto Carta Blanca (Vocalion 8677)

This early version is by the family group where Lydia Mendoza got her start in San Antonio, notable for the somewhat discordant vocal work.

“En El Rancho Grande” by Xavier Cugat (Victor 24673-A)

Listen to the unusual conga arrangement by the famed Cuban-American

bandleader and his Waldorf–Astoria Orchestra. Subtitled “Mexican Cowboy Song,” the recording actually opens with the chorus line from a Cuban standard (Miguel Matamoros’s “Buchipluma Na’ Ma’ ”) before segueing surprisingly into “Rancho Grande” with a vocal chorus and muted trumpet. Very cool.

“Alla En El Rancho Grande” by Mariachi Mexico de Pepe Villa (Camden 95-75)

An excellent, straight-up mariachi performance by this top-notch

ensemble, featuring the virile vocals of Emilio Galvéz. The sound quality on this 45-rpm is unusually clear.

ensemble, featuring the virile vocals of Emilio Galvéz. The sound quality on this 45-rpm is unusually clear.

“Alla En El Rancho Grande” by Antonio Bribiesca (Columbia DCA-192)

A low-key instrumental on an album featuring the Mexican-style guitar of

Antonio Bribiesca. The solo harmonica interlude lends a nostalgic, round- the-campfire ambiance.

“Alla En El Rancho Grande” by Frank Padilla y Su Guatemala Marimba Serenaders (Columbia 3035-X)

This marimba version on New York-based Columbia Records is notable for the arrangement attributed to Silvano Ramos, the composer who sued to claim his copyright in the U.S.

– Agustín Gurza

Blog Category

Tags

Images