This past February 22 marked the 103rd anniversary of the assassination of Mexico’s first revolutionary president, Francisco Madero. And like other historic events, Madero’s tragic deposition and death are documented through historic reenactments that were recorded to give a pre-television public the sense of personally witnessing events. Today, we can listen to those recordings on our computers, thanks to digital copies of those 78-rpm discs found in the Frontera Collection.

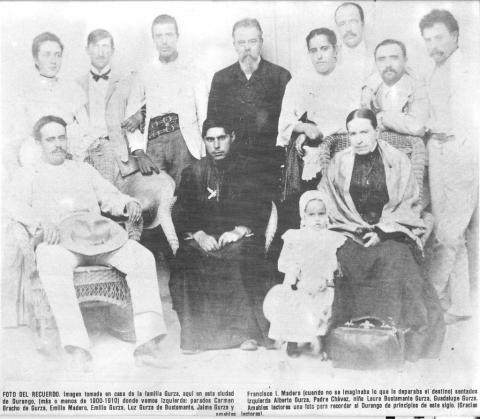

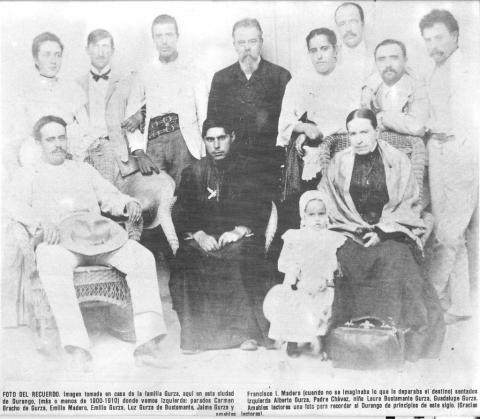

First, full disclosure: I am related to President Madero via my family in northern Mexico, and there was even a relative in his cabinet, Jaime Gurza, Secretary of Communications. The accompanying photo, taken in Durango in the decade before the revolution of 1910, shows various members of the Gurza clan with Madero (standing second from right). The newspaper caption notes ironically that the photo of the future president was taken at a time “when he could not imagine what destiny had in store for him.”

Madero, the mild-mannered son of wealthy landowners, was an author and an idealist whose writings helped spark the Mexican Revolution of 1910. In May of the following year, dictator Porfirio Diaz was forced into exile. Within days, Madero made a triumphant entry into the capital, greeted by jubilant crowds shouting, “¡Viva Madero!”

You get a sense of that boisterous, ebullient moment in this recorded re-creation, straightforwardly titled,

“Llegada De Madero A La Ciudad De Mexico” (literally, “Arrival of Madero to Mexico City”). Interestingly, the story is told from the perspective of people in the crowd waiting for Madero’s arrival by train. In a half-humorous, colloquial dialogue, they express their excitement, estimate the size of the huge crowd, and talk about how hungry they are because they’ve been waiting so long to get a glimpse of their hero.

On the recording, you hear train whistles as the locomotive approaches; the crowd cheers and happy music from a military band starts playing. The recording closes with shouts of “viva” for various leaders, including two of Madero’s brothers, Gustavo and Raul. Finally, there’s a cheer for Madero as leader of the Revolution – “¡Viva el jefe de la Revolución!” But the final shout-out is for Francisco Leon de la Barra, the Diaz regime holdover, who in 1911 served as provisional president for less than six months: “¡Viva el Presidente de la República!”

That morsel of historical trivia points to the potential educational uses of these historical recordings. A high school history teacher, for example, could encourage students to study these dramatized accounts, discuss the characters, and see how faithfully the reenactments reflect the real facts.

Students of history can relive another important chapter of Madero’s revolt in the dramatization titled,

“Salida Del General Porfirio Diaz (en el Puerto de Veracruz).” This mini-play, sounding a lot like the old radio dramas of the 30s and 40s, reenacts the moment the deposed dictator boarded a ship at the port of Veracruz that would take him into exile in Europe. At first it seems to glorify the ousted strongman, with a military flourish and cheers for Diaz and yet another historical figure, Victoriano Huerta, the military leader who would soon turn against Madero.

After a pompous and patriotic introduction, Diaz addresses the assembled crowd to say goodbye, invoking the usual symbols of righteousness – the homeland, the flag, and the Almighty. Diaz then wraps his defeat in patriotism: “Gentlemen, I have resigned because I want no more Mexican blood to be shed” (“Señores, he renunciado porque no quiero que se derrame más sangre mexicana”). And his voice chokes up when he mentions his children and the gathered military cadets, whom he considers his extended family.

Then, we finally hear the vox populi, people in the crowd speaking in a vernacular that’s in sharp contrast to the stiff and formal language of the military speeches. One man asks why Diaz got a presidential send-off when he had already resigned his post (“si ya dejó la chamba”). They must be under orders, responds another man, and orders must be followed. That brings a retort extolling the new freedoms for people under Madero, closing the recording on a revolutionary note (“Gracias a Madero, todos podemos gritar recio y gordo”).

Interestingly, before the final “vivas” for Veracruz, the telegraph operator is heard dictating a dispatch for the media about the day’s events. His message, though, is couched in glowing terms for Diaz, fervently wishing his speedy return. A listener might take it as a satirical jab at official accounts of history, especially since onlookers listen in with an edge of skepticism, laced with slang: “A ver que frijoles va a echar.” Literally that means, “Let’s see what beans he’s going to spill.” But I doubt it’s meant in the sense of revealing secrets, as we understand the saying in English. The comment suggests something more like, “Let’s see what baloney he’s serving up this time.”

One final fact: the telegraph bit allows mention of the exact date and time the people said their final goodbyes to the ex-president – “31 de mayo de 1911 a las 5:45 p.m.”

The narrator on these historic recordings, and on many others in the Frontera Collection, is credited as

Julio Ayala. There is little information available on Ayala, and it’s not clear if he is also the voice actor doing the recorded dialogues. (Ayala also has some vaudeville-style comedy skits included among his 34 recordings found in the archive.)

Another Ayala sketch recreates a speech given by Madero in the city of Puebla on July 18, 1911, one month after his arrival in Mexico City. Madero gave many speeches throughout the country that were often well received. In this recording,

“Discurso De Francisco L. Madero En Puebla La Tarde Del 18 de Julio de 1911,” the narrator sets the scene: Madero standing before a statue of President Benito Juarez, who in the late 1800s advocated for separation of church and state, antagonizing the traditionally powerful Catholic Church. Madero defends Juarez, stating that he was not anti-clergy as critics claimed. But he goes on to condemn wealthy priests (“

No quiero sacerdotes ricos”), and also calls for religious tolerance. At the end, he urges all Mexicans to come together in unity and brotherhood. It is a time for peace, he says to military fanfare, because “hostilities have ceased.”

That was certainly premature. Hostilities in Mexico were just getting started. Madero was elected president in November of 1911 and less than two years later, he was dead. The story of his ouster is one of betrayal and backstabbing by Huerta, who conspired with the U.S. ambassador to stage a coup. Huerta had Madero imprisoned, along with his loyal vice president, José María Pino Suárez. They were shot and killed while being transported to Lecumberri prison, in northeastern part of today’s Mexico City, ostensibly for their own protection. Guards claimed they tried to escape, but many people believe Huerta had ordered the assassinations.

So now Huerta, the hated traitor, turns up in another recording, calling for peace in a strange speech to Congress less than two months after Madero’s murder. In

“Discurso Del C. Presidente Gral. DN. Victoriano Huerta,” delivered on April 10, 1913, the new president proclaims his religious leanings and his indigenous roots (he was of Huichol ancestry). Then he calls for building schools and helping the Indians by the government imparting “the Eucharistic bread of education” (

el pan eucarístico de la educación). Finally, in the name of God, Huerta calls for Mexicans to “work united for the good of the country, this country so beautiful and so unfortunate” (“

Trabajemos unidos por el bien del país, este país tan hermoso y tan desaventurado”).

Soon, Huerta too would be gone, exiled after the U.S. turned against him and sent Marines into Veracruz. His demise – including his eventual incarceration in Texas on charges of sedition for conspiring with Germany against the United States – provides a dramatic, almost unbelievable denouement to his life and shameful role in the revolution. Huerta is still vilified by modern-day Mexicans, who refer to him as

El Chacal (“The Jackal”) or

El Usurpador (“The Usurper”).That sentiment is well captured in this corrido entitled,

“Crimenes De Huerta,” by Los Llaneros De San Felipe.

Huerta, el verdugo tirano, ya se fué para la europa,

Dejando el suelo manchado con sangre de mi patriota.

Recordará Huerta siempre que un delito cometió,

Y que al noble de Madero vilmente lo asesinó.

The political crisis in Mexico City leading up to Madero’s downfall and death is known as “

La Decena Trágica” (“Ten Tragic Days”). I couldn’t find a historic recording dramatizing the assassination itself. But you wouldn’t need one if you had access to amazingly vivid accounts in American newspapers of the day.

The Washington Times of February 23, 1913, ten days after the fact, carried a banner headline blaming Huerta for the killings. And

The Sun, a New York weekly, gave a riveting chronicle of Madero’s final hours in its edition of Thursday, February 27, 1913. The graphically staggered headlines evoke the sense of crisis:

MADERO AND SUAREZ SHOT

DEAD ON WAY TO PRISON

The Deposed President of Mexico and His Vice-President Die De-

fenceless (sic) on a Midnight Ride from Palace to Penitentiary,

and the Whole Civilized World Stands Aghast.

GUARDS SAY THEY TRIED TO “ESCAPE.”

In this digital age, it is hard to imagine a time when news was not available instantly. We’re used to witnessing historic events, from assassinations to tsunamis, as they happen.

A century ago, however, news didn’t travel so fast, and of course there were no sound or images in print, which was how most people got their news. So from the very early days of the recording industry, attempts were made to bring some immediacy to news accounts by re-enacting and recording historic events. These dramatizations brought print accounts to life, creating the “you-are-there” feeling long before newsreels actually brought events to movie audiences. Recorded reenactments of historic events even date back to the late 1880s,

available on early cylinders for 50 cents each.

In Mexico, the great muralists also worked to capture the dramatic sweep of history through their grand and colorful paintings. Madero’s story is vividly represented in a 1969 work by

Juan O’Gorman which carries the revolutionary’s slogan as its title,

“Sufragio efectivo – No reelección.” (Waiting for this link to load is worth it, allowing a virtual exploration of many mural details.) The mural shows Madero leaving Chapultepec Castle on April 9, 1913, the start of the Ten Tragic Days. The principled speech he is to deliver is unfurled at the feet of his white horse. To the left, Huerta and Wilson, the U.S. ambassador, conspire in a corner, their dark betrayal symbolized by two hyenas above them. To the right, we see the vice president and Madero’s wife, Sarah Perez, who pleaded with the American ambassador to protect her husband, to which he responded that he couldn’t interfere in Mexico’s internal affairs.

These corridos provide another example of how the arts in many forms – music, painting, theater, and writing – help keep history alive.

-Agustín Gurza

Viva Gurza

by Marlowe J. Chur... (not verified), 03/10/2016 - 13:41Good job!