From Columbus to Hidalgo: Hispanic Heritage on Record

Hispanic Heritage Month isn’t what it used to be. This year, it seems to have come and gone with minimal fanfare. The celebration has perhaps outlived its purpose, as Latino culture has become more mainstream since it was launched by President Lyndon Johnson at the peak of the Civil Rights era.

Hispanic Heritage Month isn’t what it used to be. This year, it seems to have come and gone with minimal fanfare. The celebration has perhaps outlived its purpose, as Latino culture has become more mainstream since it was launched by President Lyndon Johnson at the peak of the Civil Rights era.

When it started in 1968, the event only lasted a week. Twenty years later, it was expanded by President Ronald Reagan to cover a full month, from September 15 to October 15. Two historical markers served as bookends: the annual mid-September celebration of Latin America’s independence from Spain, and the mid-October recognition of Columbus Day.

Heroes and villains are often celebrated and reviled in Latin American pop music. So it’s no surprise that the Frontera Collection would include songs that suit historic occasions.

In the case of Columbus, public enthusiasm for honoring the intrepid Italian mariner has waned in the United States and elsewhere; he’s been knocked from his explorer pedestal by charges of greedy imperialism and cruelty towards Native Americans. In Mexico, people celebrate instead el Día de la Raza, in honor of the multi-racial mixture that defines the New World.

The year 1992 marked the 500th anniversary of Columbus’s first voyage, a milestone that yielded a popular salsa song. It’s performed by Venezuelan salsa star Oscar D’León, and titled simply with the explorer’s Spanish name, “Cristóbal Colón.” The song is a catchy and well-crafted narrative of the historic journey, with the usual heroic overtones. That same year, by contrast, Panamanian singer-songwriter Rubén Blades marked the occasion with a somber composition, more critical than celebratory. Titled “Conmemorando,” it diverges from the trite details taught in grammar school, offering instead a piercing, multi-layered sociological portrait of the explorers and their exploits. Touching on the ideals (the spirit of discovery) as well as the evils (the genocide of Native Americans) of the historic journey, Blades concludes with this ambivalent protest:

The year 1992 marked the 500th anniversary of Columbus’s first voyage, a milestone that yielded a popular salsa song. It’s performed by Venezuelan salsa star Oscar D’León, and titled simply with the explorer’s Spanish name, “Cristóbal Colón.” The song is a catchy and well-crafted narrative of the historic journey, with the usual heroic overtones. That same year, by contrast, Panamanian singer-songwriter Rubén Blades marked the occasion with a somber composition, more critical than celebratory. Titled “Conmemorando,” it diverges from the trite details taught in grammar school, offering instead a piercing, multi-layered sociological portrait of the explorers and their exploits. Touching on the ideals (the spirit of discovery) as well as the evils (the genocide of Native Americans) of the historic journey, Blades concludes with this ambivalent protest:

Positivo y negativo se confunden en la herencia del 1492.

Hoy, sin ánimo de ofensa hacia el que distinto piensa,

Conmemoro, pero sin celebración.

More recent songs on the topic are much less forgiving. Earlier this year, the Spanish duo Beauty Brain released a ferocious critique of Columbus, with a reggaeton beat. The title makes the act of colonizing sound pornographic: “Te Coloniso.” The merciless musical appraisal of the explorer is also found in songs by five rock-en-español bands from Argentina, Chile, and Peru, compiled in this article from 2016 on an entertainment website based in Lima. It’s titled, “5 Bandas de rock que cantan al ‘descubrimiento’ de América,” with ironic quote marks on the Spanish word for discovery.

In the Frontera Collection, I could find only one song about Christopher Columbus, but there’s no way to discern its point of view, because it’s an instrumental. The composition, “Christopher Columbus,” is a salsa takeoff on the old jazz standard by Leon Berry and Andy Razaf, who wrote humorous lyrics for the tune. It was famously recorded by Fats Waller, who had a novelty hit with the song in 1936.

The Frontera version, however, is by the legendary Machito y Sus Afro-Cubans, with a mambo arrangement by René Hernandez, the acclaimed Cuban pianist and composer. The archive has two recordings of the tune, both on Seeco Records. The earlier one is a 78-rpm disc with the title translated to Spanish, “Cristobal Colón.” A subsequent 45-rpm release uses the original English title. On both discs, Razaf is credited as co-composer even though his lyrics are not used.

By contrast, the musical celebration of political independence from Spain, after 300 years of colonial rule, is much less controversial. Earlier this year, I wrote about recordings of national anthems from Mexico and South America, and how they reflected the struggle for sovereignty and identity in the New World.

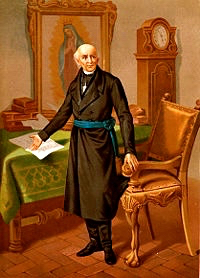

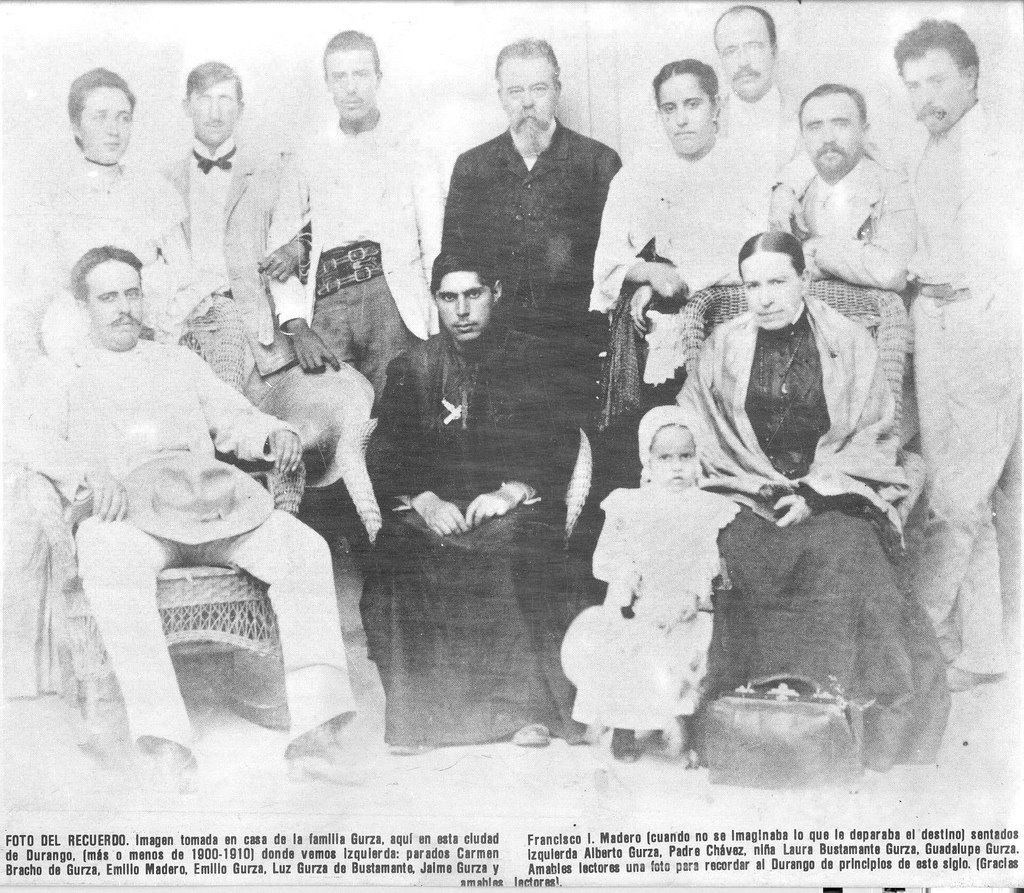

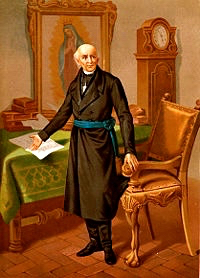

The Frontera Collection also features several recordings that specifically pay tribute to the colonial country priest who sparked Mexico’s uprising against Spain. Father Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla is considered the father of modern Mexico, honored, like George Washington in the United States, with statues, heroic portraits on famous murals. His image appears on paper currency, and streets are named after him in almost every rural town and big city throughout the country.

The Frontera Collection also features several recordings that specifically pay tribute to the colonial country priest who sparked Mexico’s uprising against Spain. Father Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla is considered the father of modern Mexico, honored, like George Washington in the United States, with statues, heroic portraits on famous murals. His image appears on paper currency, and streets are named after him in almost every rural town and big city throughout the country.

In the early morning hours of September 16, 1810, Hidalgo issued his historic battle cry for independence, ringing the bell of his parish church and calling the people to arms. Based in the town of Dolores, Guanajuato (now Dolores Hidalgo), the parish padre called to arms his parishioners, mostly poor indígenas and mestizos, in a battle against social inequality and the ruling white upper class. One of his famous cries carried overt racial and nationalist overtones: “Muerte a los gachupines” called for the death of Spaniards with a pejorative term for the colonizers.

Mexicans celebrate the holiday every year at midnight on the eve of Independence Day, September 16. In the capital, the Mexican president traditionally re-enacts Hidalgo’s cry from a balcony of the National Palace, ringing the very same bell used by the priest as a clarion call to war.

The Hidalgo narrative has gained mythical proportions: a David-and-Goliath struggle by an upstart cleric against a powerful, entrenched empire, all against the backdrop of Napoleon’s conquest of Spain two years earlier. The reality, however, is a mix of heroism and human failings. Hidalgo’s rag-tag army committed atrocities, which he sometimes ordered but later regretted. And unlike George Washington, Hidalgo was a better priest than a general. He blundered into defeats and soon had to flee in a vain attempt to regroup.

In less than a year, Hidalgo and his men were captured and executed by the royalist forces.

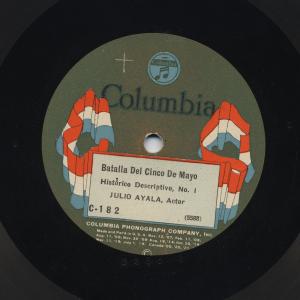

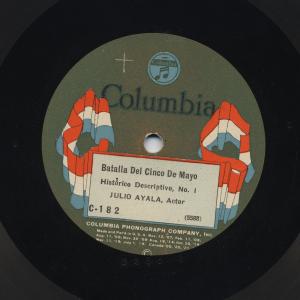

Hidalgo’s tragic demise brings us to an unusual series of recordings about his execution. It’s called “Fusilamiento de Hidalgo” by Julio Ayala, and it comes in three parts on 78-rpm discs (links included below). The series is a historical narrative of events, dramatically re-enacted by voice actors, as you might imagine an old radio program.

Hidalgo’s tragic demise brings us to an unusual series of recordings about his execution. It’s called “Fusilamiento de Hidalgo” by Julio Ayala, and it comes in three parts on 78-rpm discs (links included below). The series is a historical narrative of events, dramatically re-enacted by voice actors, as you might imagine an old radio program.

Multi-part recordings, especially corridos, were common in the early days when records had one song per side, as I explained in my series on corridos published on our blog last year. But the odd number of installments in the Hidalgo story is rare, and slightly puzzling. The three parts are on two discs, which have a total of four sides; the fourth side features a totally unrelated novelty song about a heart-broken drunk, “El Borrachito de Manzanares,” by the historic duet Rosales y Robinson.

The three-part Hidalgo recording is listed in the indispensable reference book by Richard K. Spottswood, entitled Ethnic Music on Records: A Discography of Ethnic Recordings Produced in the United States, 1893 to 1942. The guide shows Part 1 starting on the disc numbered Columbia C-155, with Parts 2 and 3 continuing on Columbia C-156. It would seem more logical to put the first two parts on one disc, and leave the last part by itself on the second disc. In any case, customers had to buy both records to hear the whole story.

Part 1 opens with the capture of Hidalgo on March 21, 1811, as a result of what the narrator describes as “the terrible betrayal” of a military officer who led the insurgents into an ambush. The rebel priest had fled north, hoping to replenish his supply of weapons in the United States. Hidalgo and his men were captured at the wells of Acatita de Baján, in my home state of Coahuila. The dramatization includes a historical detail that underscores the tragic loss: At one point, Ignacio Allende, the only rebel leader to mount a resistance, cries out that his son has been killed. This ended his will to fight.

From there, the prisoners were sent to Monclova and Chihuahua to meet their fates. The episode ends with royalists rejoicing at the capture of the insurgents, shouting “Viva el Rey! Mueran los Insurgentes!”

The second disc in the Frontera Collection (C-156) is the one with the error in identifying the sides. It seems that the labels were flipped, putting the label for part 2 on part 3, and vice versa. The mistake is obvious because the narrator on the recordings starts each side by announcing the part that is about to play.

In Part 2 (labeled part 3), we hear the sounds of execution, as Hidalgo’s co-conspirators face the firing squad. The narrative holds true to history. Some are shot in the back as traitors. A handful of leaders are called out from their cells – Ignacio Allende, Juan Aldama, Mariano Jimenez – and allowed a five-minute visit with Hidalgo before their executions. The dialogue of the meeting is dramatic and heroic, with a composed Hidalgo offering words of comfort and courage. A final prisoner, Mariano Abasolo, who helped finance the insurrection, was spared execution and was sentenced to prison in Spain, where he died.

The side ends with more bloodthirsty war cries: “¡Mueran los enemigos de la religion! ¡Así acabamos con todos los rebeldes!” (Death to the enemies of religion! Thus we will finish with all the rebels!).

Part 3 (labeled Part 2) completes the tragedy with the execution of Hidalgo on July 30, 1811. By then, he had already been ignominiously defrocked by the Catholic Church.

The final episode opens with the insurgent interacting warmly with his prison guards whom he had befriended, a fact confirmed by historical accounts. He thanks them for their compassionate treatment during his imprisonment, and leaves them verses of gratitude written with coal on the wall of his cell. It closes with his botched execution, which took two volleys from the firing squad and a final coup de grâce.

On the recording, Hidalgo is heard shouting final words of defiance. A commander then shouts a final order to his troops: “Kill him to silence him!”

It would take ten more years of war before Mexico would win its independence from Spain.

The Frontera Collection has a few other recordings dedicated to Miguel Hidalgo, mostly patriotic songs in his honor.

A Hidalgo by Gaston Flores (Brunswick 40128-B) is exactly what the genre on the label describes: a patriotic hymn, or Himno Patriótico. It’s full of purple prose in an operatic tenor. The singer, popular in Mexico in the 1920s, is backed by the label’s studio orchestra, Banda Brunswick, with military-style touches to the symphonic arrangement. Curiously, the label provides an incorrect English title based on the generic meaning of the word hidalgo, “To the Noble,” losing the real Hidalgo in translation.

A Hidalgo by Gaston Flores (Brunswick 40128-B) is exactly what the genre on the label describes: a patriotic hymn, or Himno Patriótico. It’s full of purple prose in an operatic tenor. The singer, popular in Mexico in the 1920s, is backed by the label’s studio orchestra, Banda Brunswick, with military-style touches to the symphonic arrangement. Curiously, the label provides an incorrect English title based on the generic meaning of the word hidalgo, “To the Noble,” losing the real Hidalgo in translation.

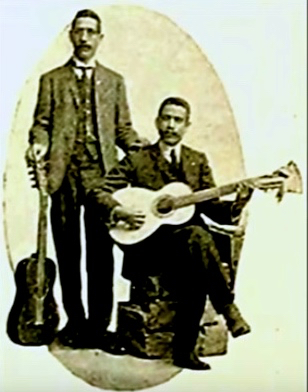

Himno A Hidalgo by Abrego y Picazo (Columbia C-434), is another paean to the priest, this one by an old-timey duet with the spare backing of a single guitar. It ends on a glorious note, quoting Hidalgo’s battle cry, “¡Libertad o morir!”

Viva Hidalgo by Alejandro Luna y Reginaldo Delgado (Bluebird B-2220-B) is labeled as a “Marcha Canción,” with a duo guitar accompaniment. The melody is catchy and the tone is upbeat, with a more modern sound. The most interesting feature is the guitar work, which precisely echoes the singer in some sections, and includes a solo in the middle. The refrain says: “Por eso digo con el eco de mi voz, Que viva Hidalgo y que muera el español.”

All the recordings above are on 78-rpm discs from the first half of the 20th century. My favorite, however, is a much more recent recording from a 33-rpm album, entitled Jose-Luis Orozco Canta 160 Años del Corrido Mexicano y Chicano. The song, “Miguel Hidalgo,” was co-written by the respected author and corrido expert, Vicente T. Mendoza.

The corrido takes a more biographical approach, with verses sketching Hidalgo’s birth, education, and varied skills. Orozco, the singer, has that folksy authenticity characteristic of artists from the socially conscious New Song movement that swept Latin America in the 1960s and ’70s.

Yet, the song ends in a most traditional manner with the singer’s farewell (despedida), a classic element of Mexican corridos.

Ya con esta me despido, con luto en el Corazón,

Y aquí se acaba el corrido del padre de la nación.

– Agustín Gurza

Tags

Images