the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center,

the Arhoolie Foundation,

and the UCLA Digital Library

In my last blog, I looked at the history of disaster songs and cited some examples from the Frontera Collection. But, as it turns out, one of the most original and provocative songs of this genre is about a disaster that never happened.

“Cataclismo En Pinotepa” by Los Andariegos (Alborada AB-00301) is a song about the public panic that gripped the town of Pinotepa Nacional, southeast of Acapulco, in 1977 after newspapers reported scientific predictions of an impending earthquake. That controversial prediction was based on a published study by seismologists in the United States who noted a long-time gap between major quakes in the state of Oaxaca along the coast of southern Mexico, one of the most seismically active areas on Earth. “A firm prediction of the occurrence time is not attempted,” states the report by an international team based at the Geophysics Laboratory of the University of Texas in Galveston. “However, a resumption of seismic activity in the Oaxaca region may precede a main shock.”

Clearly, the researchers were reluctant to pinpoint a specific date for the quake, but the press and the local rumor mill quickly supplied one. Soon enough, warnings of an imminent earthquake led to a hard-and-fast conclusion that it would hit Pinotepa on Sunday, April 23, 1978. The doomed region would also be swamped by a subsequent tsunami, according to the sensationalized forecasts.

That was enough to set off a significant exodus. Panicked residents sold off their homes and belongings at a loss, then fled for their lives. "The psychosis caused by the alarming news has induced them to sell their properties to the highest bidder,” wrote two professors of geophysics from the University of Mexico, Tomás Garza and Cinna Lomnitz. “One wonders: Who are these people picking up cheap real estate along the Oaxaca coast?"

The yellow press promptly provided some wild answers to that question. One Acapulco newspaper reported that “a foreign power” had embedded nuclear charges within the quake fault off the Oaxaca coast and planned to detonate them on April 23 by remote control from a passing plane. Most people dismissed that account as too bizarre to be believed. But many residents were convinced that oil or uranium reserves had been discovered in the area, and that foreign nationals were fueling the rumors to snap up cheap land leases.

Although the predicted quake did not hit on that day, the panic itself became the disaster. Property losses from the sell-off “were comparable to those sustained from an actual earthquake,” concluded Garza and Lomnitz in their study, The Oaxaca Gap: A Case History.

These “aftershocks” were primarily psychological. In the song by Los Andariegos, the lyric unleashes a bitter and blistering denunciation of the “idiot wise men” who misuse their knowledge, and the sensational press that traffics in gossip. The song, with guitar accompaniment and a mournful melody typical of the folk music of Oaxaca, opens with a blast at the “damned Yankees who announced in capital letters that Pinotepa would perish.”

Pongan cuidado, señores, lo que pasa en estos tiempos.

El ignorante la riega por su falta de talento.

Pero hay sabios que de plano son brutos de nacimiento.

Año del ’78, para que el mundo lo sepa,

Unos desgraciados yanquis anuncian con grandes letras

Que el día 23 de abril, se perderá Pinotepa.

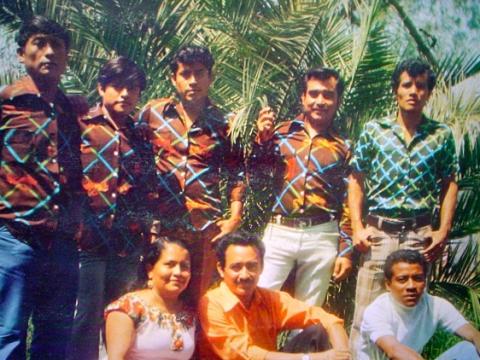

The song was written by the late Higinio Peláez Ramos, a respected composer and interpreter of the stirring and haunting folkloric music of the area. Peláez founded Los Andariegos and often sang accompanied by Fide Vera (born Fidela Vera Rodríguez), his wife and faithful musical partner. The two met in Pinotepa Nacional but had to elope to get married, slipping out of town in disguise to avoid the wrath of the bride’s father. They had several children, also musicians. Two of their daughters, Rodolfina and Fidela, are credited on the song about Pinotepa, identified in the Frontera database as “Rodi Y Fide Peláez Vera.”

The composer mercilessly skewers the press in his song, presaging the current climate of utter contempt for the media. He portrays reporters as backyard gossips who enjoy the sight of people suffering. He blames their “criminal” reporting – “without a modicum of conscience” – for driving people mad and leaving them destitute (“en la miseria”) after selling off their belongings. One verse paints a picture of mass hysteria: When the date arrived, the people were so traumatized by the spread of “exaggerated news” that even the buzzing of a fly made them nervous wrecks.

Y como si ver sufrir fuera una cosa bonita,

Los medios de difusión jugando a las comadritas

Anuncian que un maremoto se puntara a Costa Chica.

Esta criminal noticia, sin la mínima conciencia,

Provoca que mucha gente casi rayen en la demencia,

Y se queden en la miseria al vender sus pertenencias

Cuando la fecha llego, la gente traumatizada,

Hasta el zumbar de la mosca los nervios les destrozaba.

Esto hace la difusión de notas exageradas.

The composer’s parting shot carries a hint of anti-intellectualism, slamming “those who study” only to provoke unpleasantness. “I prefer being ignorant,” writes Peláez, “but not be a stupid wise man.”

En fin aquí me despido, atrás de este conducto,

Y maldigo a los que estudian para provocar disgustos.

Prefiero ser ignorante, pero no ser sabio bruto.

It turns out, however, that the songwriter, as well as other Mexican critics, would have to eat their words to some degree. A major earthquake did in fact hit the Oaxaca region, but not on the day determined by unscientific speculation. A 7.5 magnitude quake came seven months later, on November 29, 1978. Fortunately, it caused relatively little damage. A team of seismologists from Caltech and the University of Mexico heeded that forecast and set up a system of sensors that were ready when it struck. They called it “Trapping an Earthquake.”

It was a unique opportunity for measuring a quake in real time, but it came with a warning about the still developing science of earthquake predictions. “What happened to the people of that area of Mexico as a result not only of this carefully evaluated scientific prediction but also of a widely publicized non-scientific prophecy related to it, could well be the script for what could happen under similar circumstances in, for example, southern California,” wrote the late Karen McNally, noted seismologist and former director of the Richter Seismological Laboratory at UC Santa Cruz. She also noted that this case led scientists to urge the public “to prepare for handling earthquake predictions as well as actual earthquakes.”

A decade later, McNally accurately predicted the devastating Loma Prieta quake of 1989 in Northern California, which killed 57 people. McNally was ready for that one too. Instruments were installed along the San Andreas Fault when the quake hit, so the resulting recordings were the best that had been obtained to date, providing valuable information about the faults and how they behave.

As you might expect, the Frontera Collection has songs about that disaster, too. “La Tragedia De San Francisco” by Los Rebeldes del Bravo de Moises Contreras (Joey 3184) refers to the moment that the Loma Prieta quake hit on October 17 at 5:04 p.m., just as Game 3 of the World Series was about to get underway. As luck would have it, the series pitted two teams from the hard-hit Bay Area, the San Francisco Giants and the Oakland Athletics. (Toda la atención estaba a ver quien iba a ganar / Entre Oakland y San Francisco en esa serie mundial.) Suddenly, the earthquake arose “from the bowels of the Devil (de la entrañas del Diablo),” as the song vividly describes.

As I mentioned last time, the Loma Prieta quake is also the subject of a song, “El Temblor De San Francisco,” by Tex-Mex artist Steve Jordan, who was on his way from Corpus Christi, Texas, to a concert in San Francisco when the quake hit, flattening the 880 freeway “like a tortilla,” and of course cancelling the tour.

The Frontera Collection also includes songs about quakes in Nicaragua, Guatemala, and the devastating Mexico City temblor of 1985. But searching for tunes about temblors is almost as complicated as predicting them. There are at least two ways to say earthquake in Spanish. A search under the term “temblor” produces ten separate recordings, and a search by the word “terremoto” yields another five.

The results include a few two-part corridos on 78-rpm discs. However, a close listen reveals that two of those are actually the same song about the same disaster, even though they have different titles. They are “Los Temblores De Oaxaca” (Brunswick 41287, parts 1 and 2) and “Los Temblores En Mexico” (Columbia 4441-X, parts 1 and 2), written by L. M. Bañuelos and both performed by Hermanos Bañuelos (identified on the Columbia label as “Bolaños”). But which earthquakes are they singing about? Like all good corridos, the lyrics provide a clue by giving the date: January 14. However, unlike other narrative ballads, this one does not give the year. By checking a Wikipedia list of earthquakes from the first half of the 20th century, when 78s were popular, we can deduce the song is referring to the 7.8 quake that hit Oaxaca on January 15, 1931.

Some quake songs do not appear under the common search terms because those terms, like temblor and terremoto, are not in all of the titles. But these other disaster songs show up when searching the word “earthquake” in English, because it appears in the explanatory notes for some songs. So the English search gives us titles like “Tragedia De Nicaragua,” “Dolor Y Tristesa (sic) En Mexico” and “Corrido De Guatemala.”

Still, you can’t judge every disaster song by its title. There’s one called “Earthquake” that won’t even shake up the dance floor. It’s a smooth, slow-tempo instrumental by Nuyorican bandleader Tito Rodriguez, arranged by famed Cuban musician Chico O’Farrill.

Then there’s the group called California Earthquakes, which have nothing to do with natural disasters, though musically they come close. Their bilingual novelty tune “Mexican Dinner,” for example, opens with the sound of a jet engine and a narrator announcing the destination. (“Y nos vamos a la Placita Olvera a Los Angeles, California.”) The tune, a blend of Tex-Mex and ’50s rock, quickly devolves into cornball food references, including double entendres about tamales and burritos. (“Hey, gringo, de veras you like Mexican dinner?”) One verse includes a not-so-veiled threat of violence if the “Mexican Dinner” is not served up pronto.

Si tu no me das Mexican Dinner,

Me pongo muy furioso,

Y no va ser curioso.

Yo voy a enloquecer,

Si no hay Mexican Dinner.

That may not be a disaster song. But it certainly qualifies as a catastrophe.

-Agustín Gurza

0 Comments

Stay informed on our latest news!

Add your comment