the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center,

the Arhoolie Foundation,

and the UCLA Digital Library

The Frontera Collection is not a static library archive collecting digital dust. It is designed to be a dynamic, interactive cultural resource, open to contributions from researchers and music fans, as well as from friends and relatives of the thousands of artists represented in this incomparable record collection.

The Frontera Collection is not a static library archive collecting digital dust. It is designed to be a dynamic, interactive cultural resource, open to contributions from researchers and music fans, as well as from friends and relatives of the thousands of artists represented in this incomparable record collection.

Many Frontera followers have started offering feedback, comments, information, and appreciation. In some cases, their missives point us to hidden gems in the collection that otherwise may have gone unnoticed.

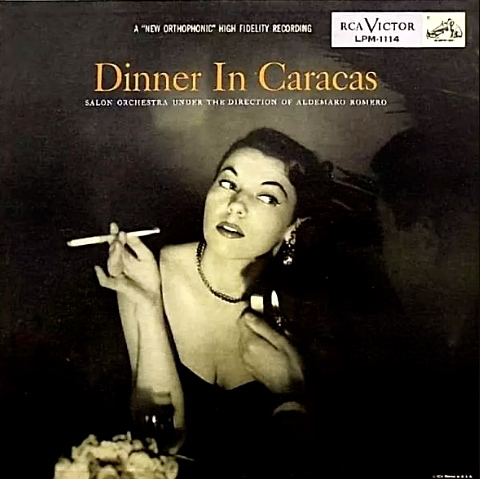

Such was the case last month when a music fan from Caracas, Venezuela, contacted us about a song called “Ay Trigueña!” by Dúo Espin – Guanipa, a guitar-and-vocal duet on a Victor 78-rpm disc. I had never heard of the artists, nor this lovely old-fashioned song about a man’s yearning for the love of a beautiful woman with a wheat-colored complexion.

The query piqued my interest.

I looked closer at the record label, by clicking on the image to enlarge it. And I found two clues to the song’s origin: It’s identified as a style known as “joropo,” and it was “Recorded in Venezuela.” Saying joropo in that South American country is like saying mambo in Cuba, or tango in Argentina. It’s not just a genre, it’s a national cultural symbol.

The man making the inquiry identified himself as Bernardo Bernal, music engraving assistant with a musical enterprise called El Libro Real, based in Caracas. The website offers a songbook of traditional Venezuelan compositions, with lyrics and musical notation, like printed sheet music distributed for centuries on paper and papyrus. The book identifies the composer of each song, and the genre. Bernal wrote to ask for the dates when songs were written or published, which we unfortunately could not provide since Frontera’s focus is on commercial recordings.

His request, however, spurred me to explore the Venezuelan music contained in our collection. Although it focuses primarily on Mexican and Mexican-American music, the Frontera Collection features a remarkable array of music from other countries and regions, including Argentina, Colombia, Cuba, Peru, Venezuela, Puerto Rico, and Spain. Each one has its own rich, regional music traditions. An unfiltered search for the term “Venezuela” yielded over 250 entries in our database.

I don’t consider myself an expert in Venezuelan music, far from it. But I know enough to appreciate it as one of the most fertile and diverse – and undervalued – schools of music on the continent. When you think of the musical powerhouses of Latin America, Venezuela doesn’t always get its due. Today, sadly, Venezuela is known more for its economic collapse and political turmoil than its musical culture. Even in more prosperous times, Venezuela was known for its productive oil fields, its stunning beauty queens, and handsomely produced telenovelas. Its native music, along with its native cuisine, have received less attention.

I don’t consider myself an expert in Venezuelan music, far from it. But I know enough to appreciate it as one of the most fertile and diverse – and undervalued – schools of music on the continent. When you think of the musical powerhouses of Latin America, Venezuela doesn’t always get its due. Today, sadly, Venezuela is known more for its economic collapse and political turmoil than its musical culture. Even in more prosperous times, Venezuela was known for its productive oil fields, its stunning beauty queens, and handsomely produced telenovelas. Its native music, along with its native cuisine, have received less attention.

Yet, the country has managed to leave its mark on modern pop music, with internationally successful artists in various fields:

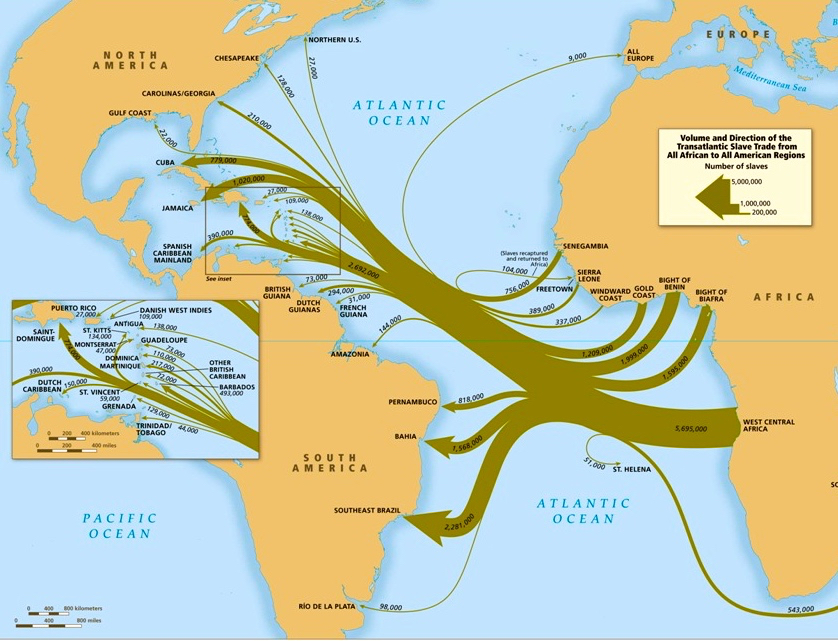

Like the other major musical strains in Latin America, Venezuela’s musical traditions share the multicultural roots that define the continent’s best sounds – a mix of European, African, and indigenous elements. It is no coincidence that some of the most rhythmic and irresistible music in the Americas comes from countries with significant black populations as a result of the Spanish and Portuguese slave trade.

Cuba, with its potent infusion of African rhythms and religious fervor, is the pulsating heart of this musical diaspora. Colombia and Venezuela, on the South American mainland, share similar traditions, along with common shores on the Caribbean Sea. Puerto Rico, Panama, and the Dominican Republic are also part of this rich tropical triangle.

Yet, it would be a mistake to lump these countries into the same musical bag. Though the roots are similar, each one has developed it own distinctive genres, with unique melodic structures, rhythmic patterns, and dance styles.

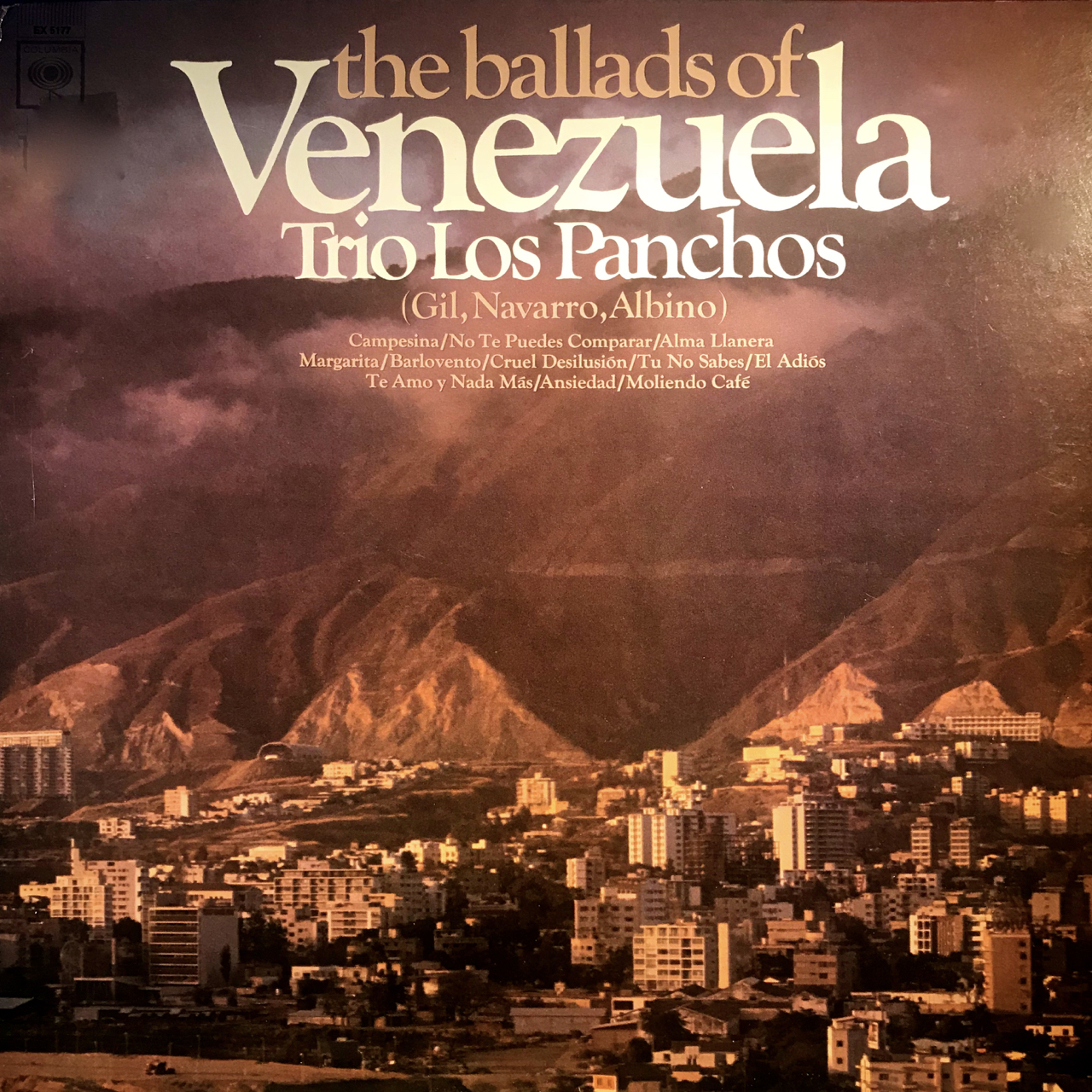

I grew up in the 1950s as a Mexican-American kid in San Jose, California, far from Venezuela both culturally and geographically. But I became aware of Venezuelan music through my father, who was an avid record collector and a big fan of Trio Los Panchos, the romantic Mexican guitar ensemble that was so popular in Mexico during the 1940s and ’50s.

One day I found an album that promised something a little different. The cover showed a bird’s-eye view of a city tucked against towering, cloud-shrouded mountains. It had a magical attraction. The title was in English, The Ballads of Venezuela, with big, bold, white lettering that stood out against the hazy, scenic backdrop.

One day I found an album that promised something a little different. The cover showed a bird’s-eye view of a city tucked against towering, cloud-shrouded mountains. It had a magical attraction. The title was in English, The Ballads of Venezuela, with big, bold, white lettering that stood out against the hazy, scenic backdrop.

The album became a favorite during my college years. The copy I now have is a U.S. release on Columbia, but it is undated and very sparsely annotated. That’s a shame, since records were always learning tools for me, a window on new music and cultures not only through the grooves, but also the liner notes. A Spanish Wikipedia page for Los Panchos lists a 1967 album titled En Venezuela, presumably the original release in Mexico.

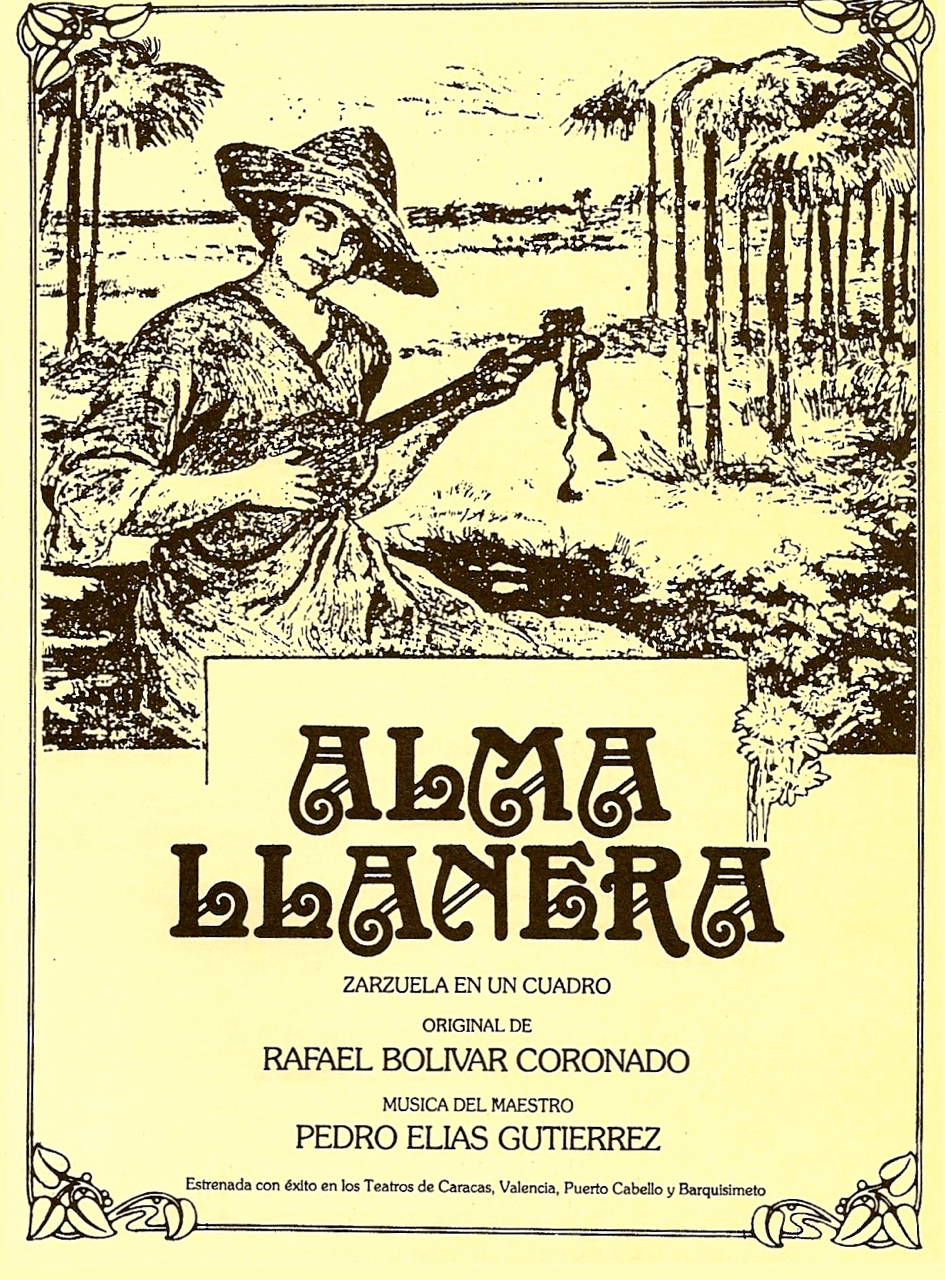

It’s not surprising that the trio would focus on songs of Venezuela. The group was popular worldwide, and Venezuela was among their fist stops on their earliest international tours in the late 1940s. Their album contains three Venezuelan songs that are standards in the Latin American songbook: “Alma Llanera” by Pedro Elías Gutiérrez, “Barlovento” by Eduardo Serrano, and “Moliendo Café” by Jose Manzo, although authorship is sometimes credited to his famous nephew, composer and arranger Hugo Blanco, who has 39 recordings in the Frontera Collection.

Those three essential songs could comprise the core of an introductory course on Venezuelan folk music. The Frontera Collection has several versions of each, linked above. They have in common a deep sense of place and identity, celebrating the beauty and customs of the country, and the countryside, always described idyllically.

“Alma Llanera” (Soul of the Plains) is a classic joropo considered a second national anthem by Venezuelans. Wikipedia has an informative description of the song and its meaning, including an English translation of the exuberant lyrics, with its catchy chorus of two-syllable verbs punctuated by full stops (“Canto, lloro, rio, sueño”), and its pastoral personification of nature providing a climactic finale (“Soy hermano de la espuma, de las garzas, de las rosas, y del sol”).

The Frontera Collection has 17 recordings of the song, in a variety of styles and arrangements. They include an almost symphonic mariachi, a guitar ensemble, a jarocho version with harp, one with refined, quasi-classical vocals, and another with a full studio orchestra.

My favorite from our list is the 78-rpm version by the Orquesta Tipica Venezolana of Manuel Briceño, on the SMC Pro-Arte label. The arrangement sparkles from the dramatic opening with a fluttering clarinet. It has a folkloric feel despite the sophisticated arrangement, which brings in the singer, Lorenzo E. Herrera, mid-way through the track. I guess it’s natural that the Venezuelans would be masters of their own music.

In hindsight, I’ve reconsidered the version I first heard by Trio Los Panchos. (The Frontera version was recorded in Mexico by Columbia and released in the U.S. by the New York–based Seeco label.) It’s pleasant enough, but now it sounds commercially processed, and slightly soulless. The same is true for the trio’s version of “Barlovento,” a 78 released on Columbia de Mexico. On my domestic Columbia LP, the title is translated as “Windward.” Actually, the song refers to a region east of Caracas where Spaniards established cacao haciendas worked by African slaves.

By contrast, listen to the elegant yet folksy version by Briceño’s Orquesta Tipica Venezolana, which transports you to a magical, tropical time and place. The label, another SMC Pro-Arte 78, identifies the song as a merengue, although it’s very different from the Dominican dance style familiar in the United States. The Venezuelan merengue has a lighter, more lilting rhythm, popular in Caracas in the 1920s as a ballroom dance for couples.

By contrast, listen to the elegant yet folksy version by Briceño’s Orquesta Tipica Venezolana, which transports you to a magical, tropical time and place. The label, another SMC Pro-Arte 78, identifies the song as a merengue, although it’s very different from the Dominican dance style familiar in the United States. The Venezuelan merengue has a lighter, more lilting rhythm, popular in Caracas in the 1920s as a ballroom dance for couples.

Merengue is one of several distinctive musical genres native to Venezuela, which often reflect regional diversity. The joropo, for example, has roots in the central plains (los llanos), featuring a distinctive Venezuelan harp. It is sometimes referred to generally as “música llanera,” but even within the category there are variations.

For example, the Frontera Collection has a thrilling song titled “Joropo Tuyero,” written by Briceño and performed by an outstanding vocalist named Alfredo Sadel, who I recently discovered through his solo albums which I happily stumbled across in used record stores. The title refers to the Tuy Valley, an area south of Caracas with its own variety of steel-stringed harp. The archive has two other versions with different vocal stylings, by Lorenzo Herrera with his Orquesta Venezolana on Columbia, and by Vicente Flores on RCA, with accompaniment by the label’s Conjunto Venezolano Victor.

Among Latin American music fans, perhaps the most widely known Venezuelan folk song is “Caballo Viejo,” written by revered singer and composer Simón Diaz, who died in 2014 at age 85. The song, about the irresistible force of a May-December romance, is sometimes identified as a pasaje, a slower, more lyrical version of the joropo. But it has been recorded scores of times in various styles, from salsa and cumbia to mariachi. Diaz himself delivers this engaging rendition, interspersed with poetry and dialog, in a live concert with a traditional folk backup band. But by far the most popular rendition is this 1981 recording by Cuban artist Roberto Torres in a novel format called charanga vallenata, a salsa fusion of Cuban and Colombian elements.

Another emblematic style, the gaita zuliana, comes from northwestern Venezuela in the region around the port of Maracaibo, in the state of Zulia. The gaita started as a grass-roots, improvised style that served as Christmas music. It gained national popularity in the 1960s, merging its melody and message with salsa and other styles, including protest music from the New Song movement.

The modern evolution of the genre is traced in a documentary telling the history of the aforementioned Guaco from Maracaibo, named for a local bird and originally known as Los Guacos de Zulia. The film title, Guaco: De Gaita Zuliana a Género Propio 1958-2004, suggests the band converted the gaita into its own, distinctive genre, incorporating elements of salsa, rock, jazz and funk without losing the Venezuelan essence.

“Gaita music was really the first, uniquely Venezuelan popular music that has a clear African-American … aesthetic foundation, although that aspect was not frequently recognized within the country,” says T.M. Scruggs, a professor of ethnomusicology at the University of Iowa who spent six years studying Venezuelan music and culture. “No one would exactly trumpet the fact, though it is clearly Afro-Venezuelan.”

Scruggs makes his comments in an informative interview published by Latino Life, a British cultural website. There are other online resources that explore Venezuelan music and culture in some depth. Smithsonian Folkways has a good introduction to música llanera, with a description of some typical instruments. The interactive music website Folk Cloud, which allows users to explore folk music worldwide by clicking countries on a map, provides samples of Venezuelan songs, with brief genre descriptions. The cultural website Carnaval.com and the travel site Venezuela Tuya both offer an overview of the music and artists, along with other cultural topics for travelers and music lovers alike.

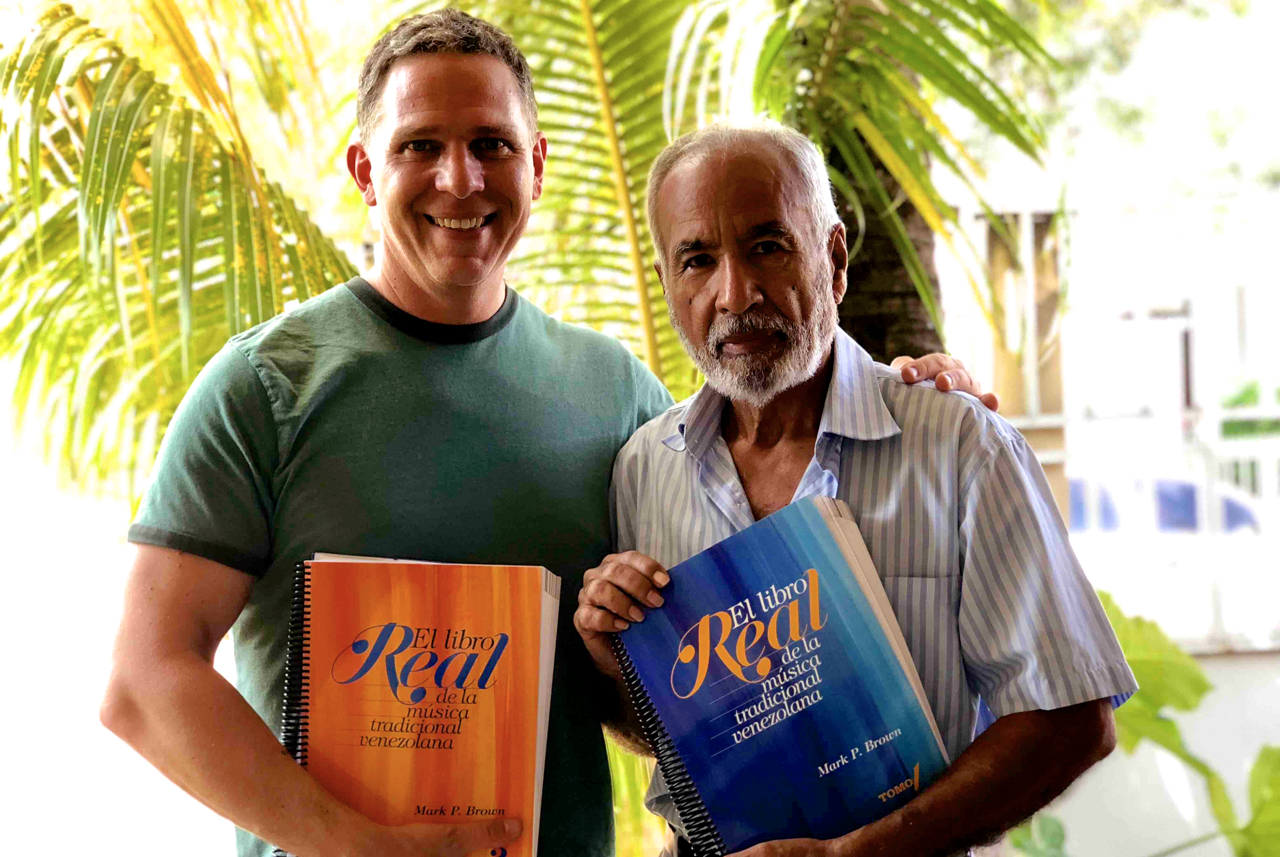

Then, of course, there’s the website that got us started on this journey. El Libro Real was founded by Mark P. Brown, a musician and instructor who was born in Queens and moved to Venezuela with his family when he was nine. He started the project of transcribing folk songs because of the dearth of published music in the country. His desire to get the most authentic renditions drove him to seek out the living composers and document their original works, a quest that took him from one side of Venezuela to the other.

Then, of course, there’s the website that got us started on this journey. El Libro Real was founded by Mark P. Brown, a musician and instructor who was born in Queens and moved to Venezuela with his family when he was nine. He started the project of transcribing folk songs because of the dearth of published music in the country. His desire to get the most authentic renditions drove him to seek out the living composers and document their original works, a quest that took him from one side of Venezuela to the other.

“The primary motive for publishing El Libro Real is to leave a record of the richness and diversity of traditional Venezuelan music … so that these pieces can be read, learned and interpreted by new generations of Venezuelan musicians,” Brown’s website states. “At the same time, it aims to recognize the valuable work of those who, through their compositions, have helped construct an essential part of Venezuela’s cultural legacy.”

That same educational mission and spirit of preservation is shared by the Frontera Collection, through its digital archive of priceless recordings representing an array of musical genres from throughout the Spanish-speaking world.

-- Agustín Gurza

1 Comments

Stay informed on our latest news!

Es realmente triste que la música folclórica de Venezuela haya s

by farandulard (not verified), 02/20/2023 - 01:35Es realmente triste que la música folclórica de Venezuela haya sido olvidada. Esta música es una parte importante de la identidad cultural del país y su pérdida es una gran pérdida para la historia y el patrimonio musical de Venezuela. Sería maravilloso que se hicieran esfuerzos para preservar y difundir esta música, de manera que las nuevas generaciones puedan conocer y apreciar su rica tradición musical

https://farandulard.net/