A Single, Overlooked Recording Opens a World of Music

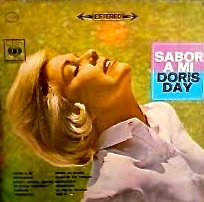

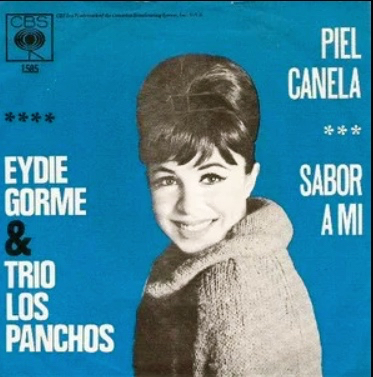

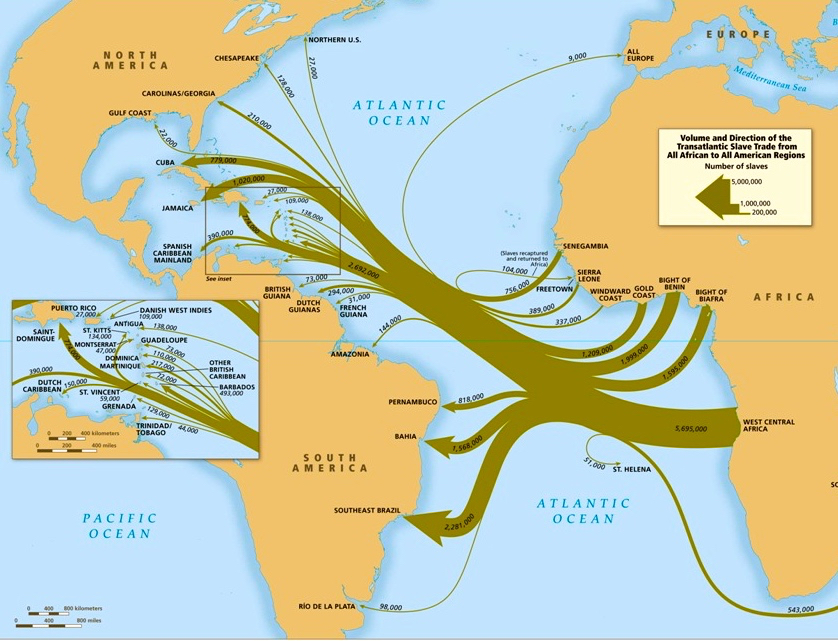

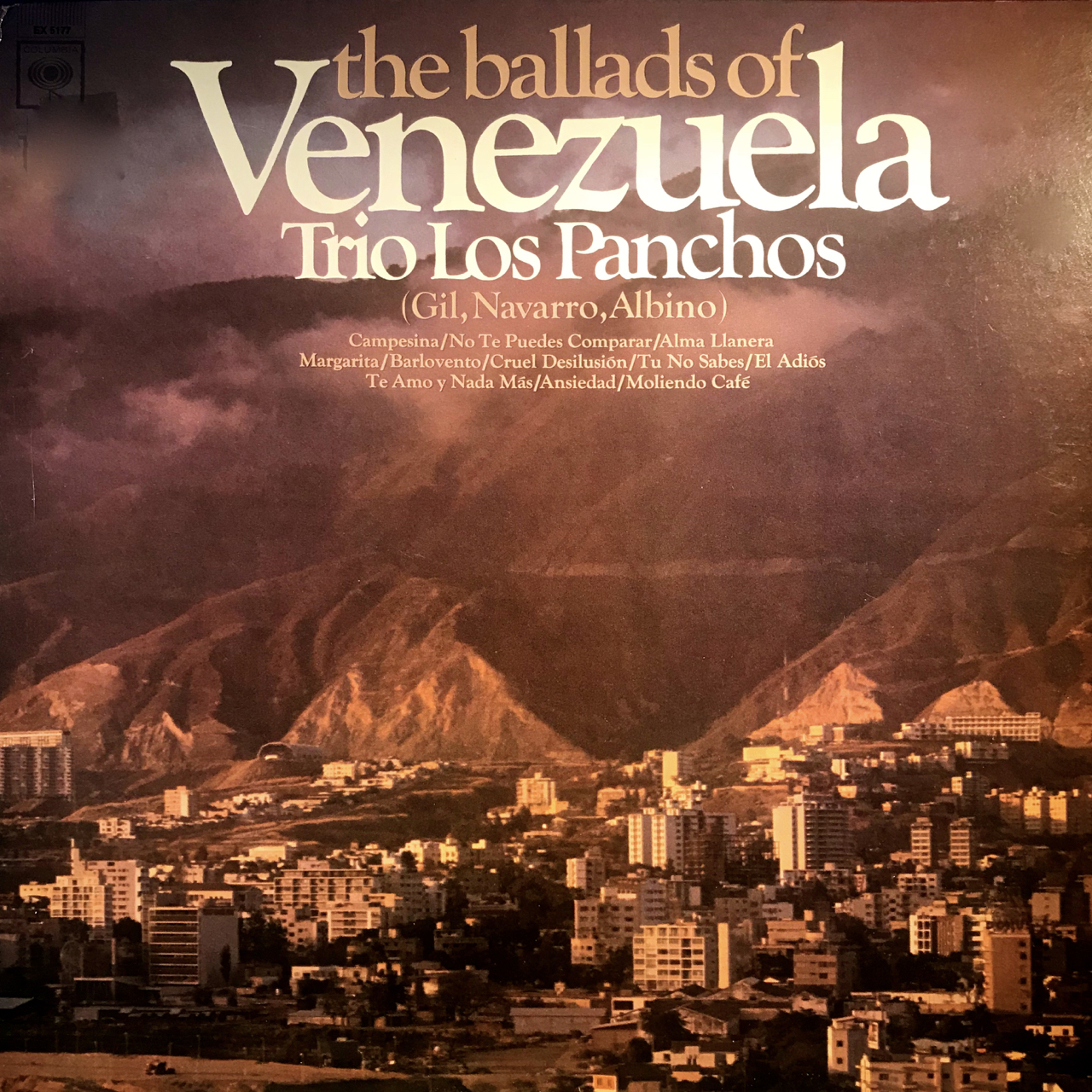

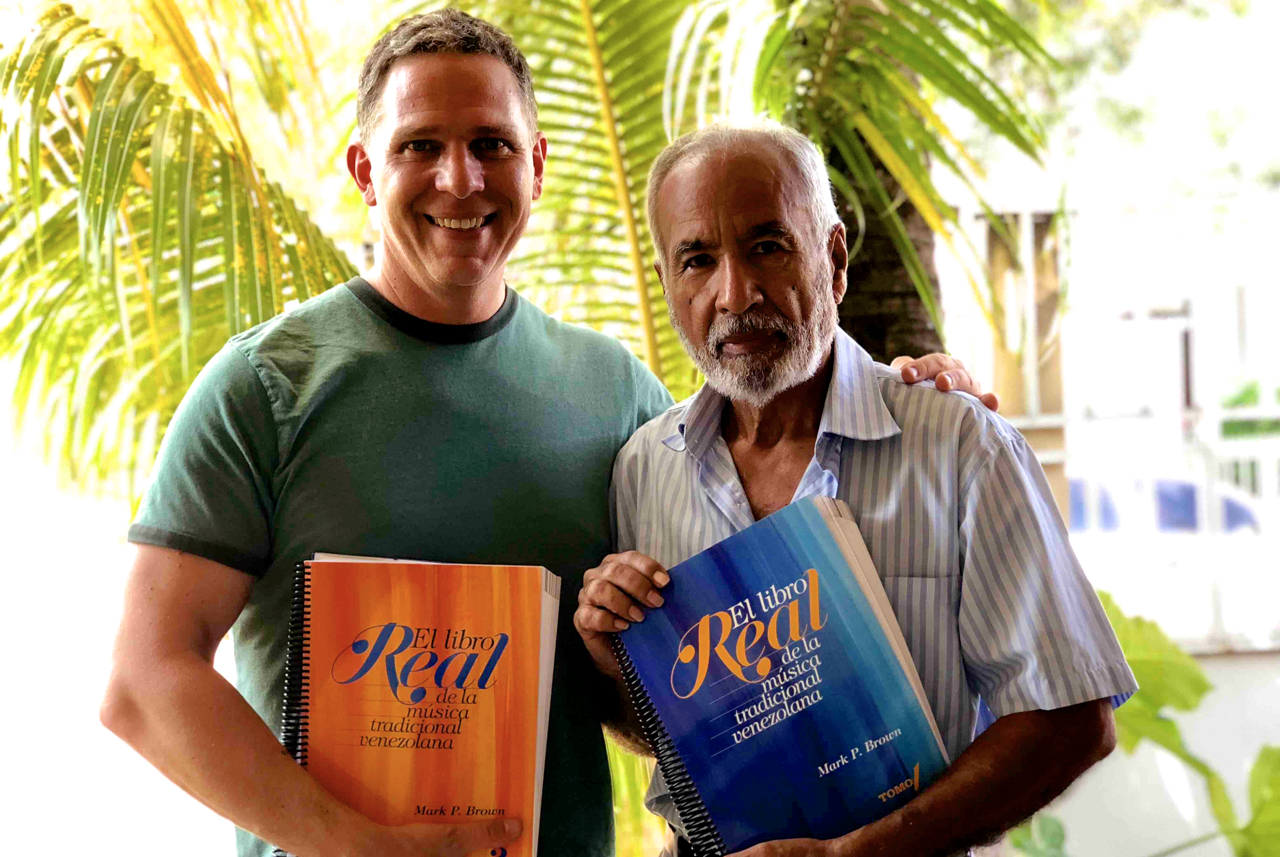

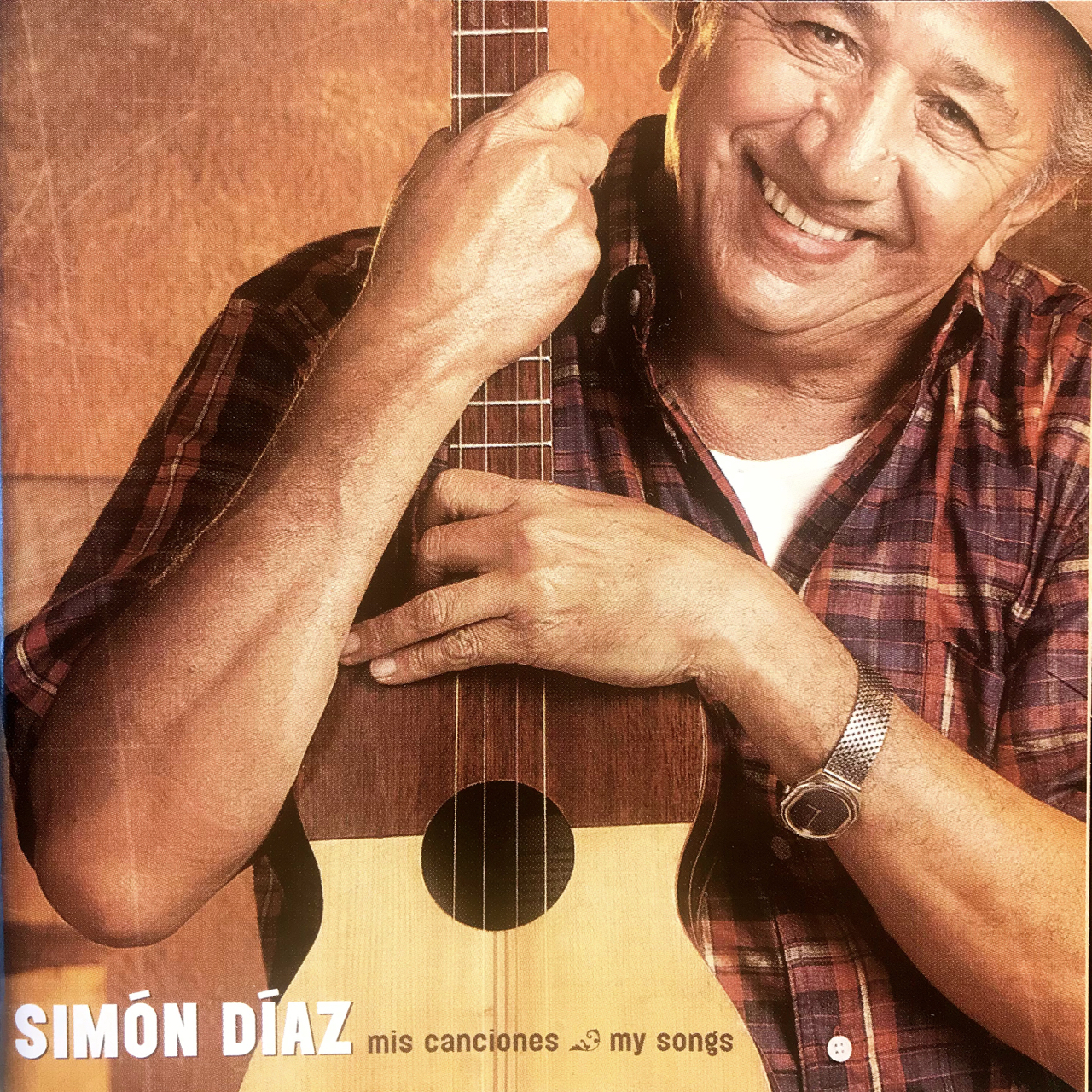

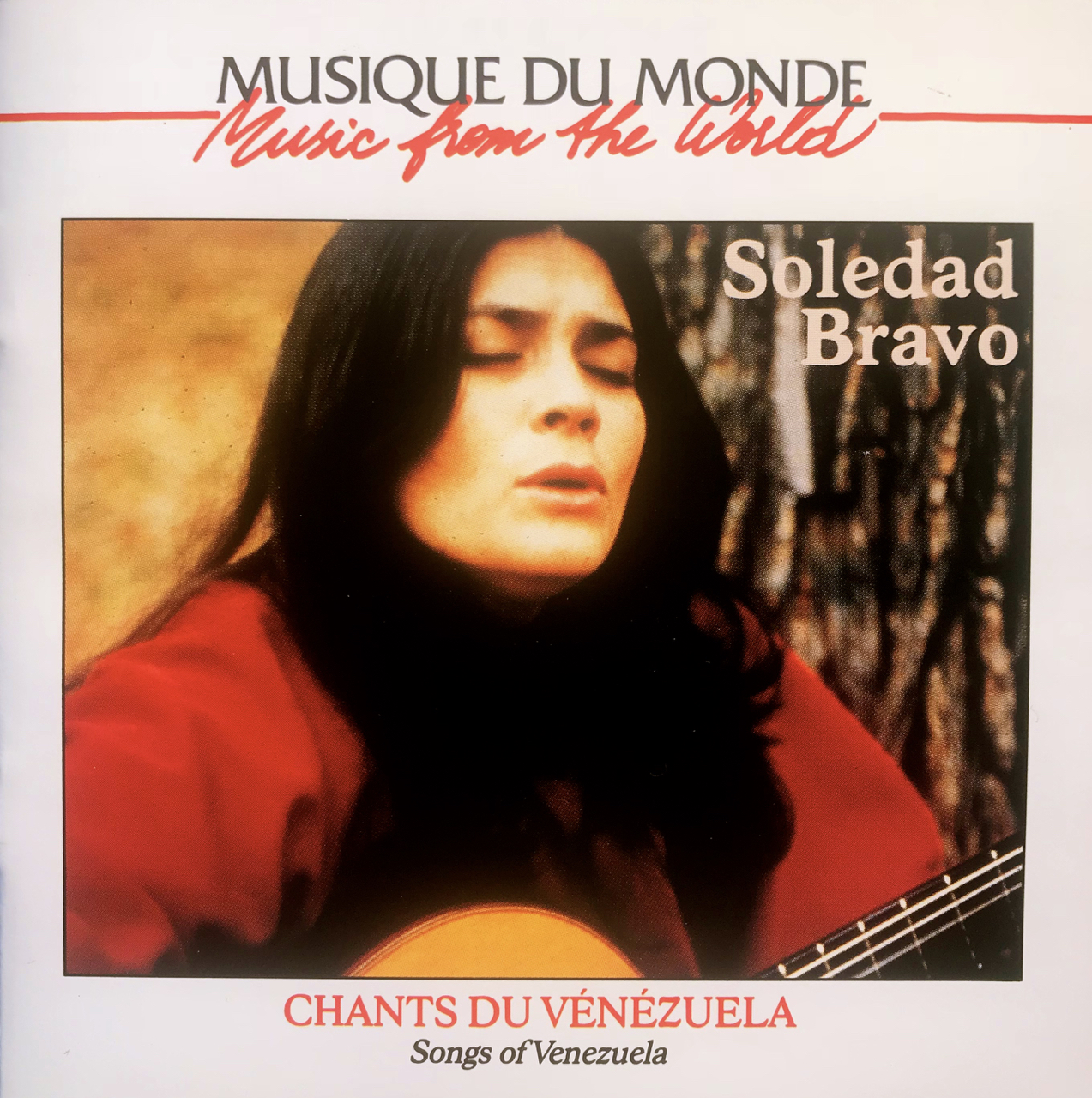

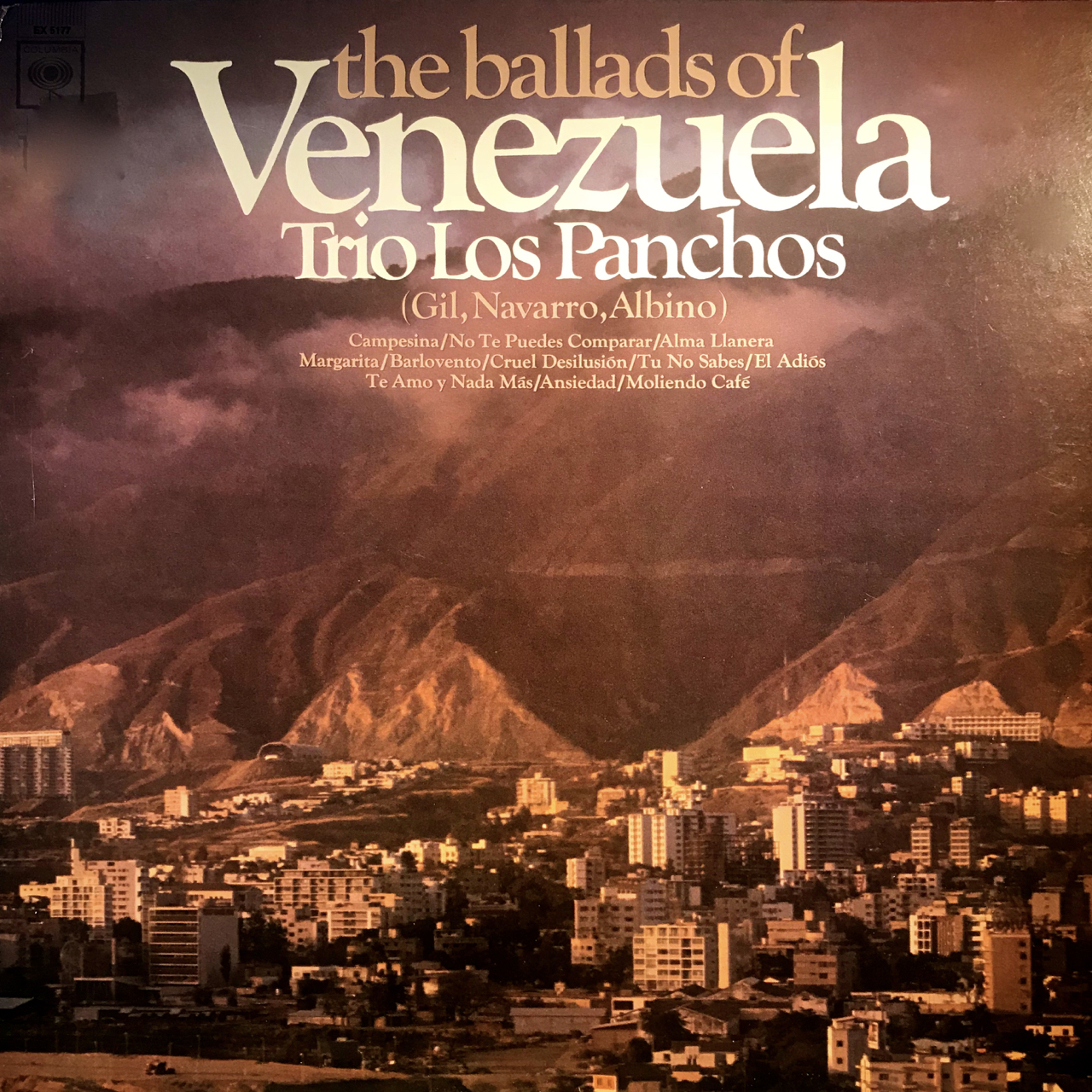

Music lovers who explore the Frontera Collection for their favorite hit songs may be occasionally disappointed or even perplexed. For example, how could a musical archive dedicated to Mexican American music fail to contain the celebrated albums by Eydie Gorme and Trio Los Panchos? Those Colombia titles were huge hits among Mexican Americans in the 1960s and have remained standards ever since.

Music lovers who explore the Frontera Collection for their favorite hit songs may be occasionally disappointed or even perplexed. For example, how could a musical archive dedicated to Mexican American music fail to contain the celebrated albums by Eydie Gorme and Trio Los Panchos? Those Colombia titles were huge hits among Mexican Americans in the 1960s and have remained standards ever since.Almost every barrio home with a record player had a copy of “Amor: Great Love Songs In Spanish” from 1964, the first in a series of collaborations between the Bronx-born Jewish vocalist and the wildly popular Mexican guitar trio. The binational act released two more successful albums in rapid succession – “More Amor” in 1965 (also issued as “Cuatro Vidas” in Mexico, with a different song sequence), and “Blanca Navidad / Navidad Means Christmas” in 1966.

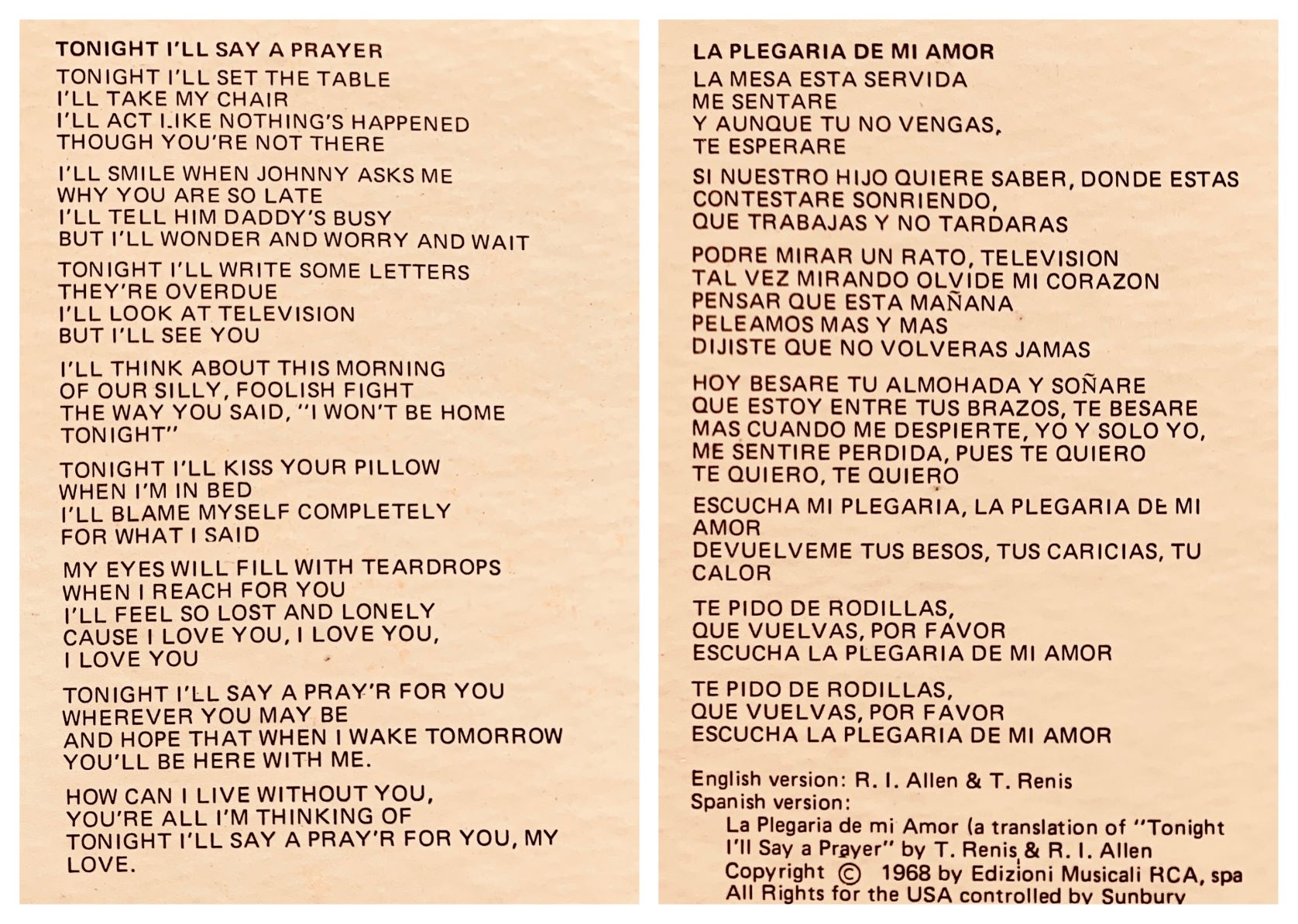

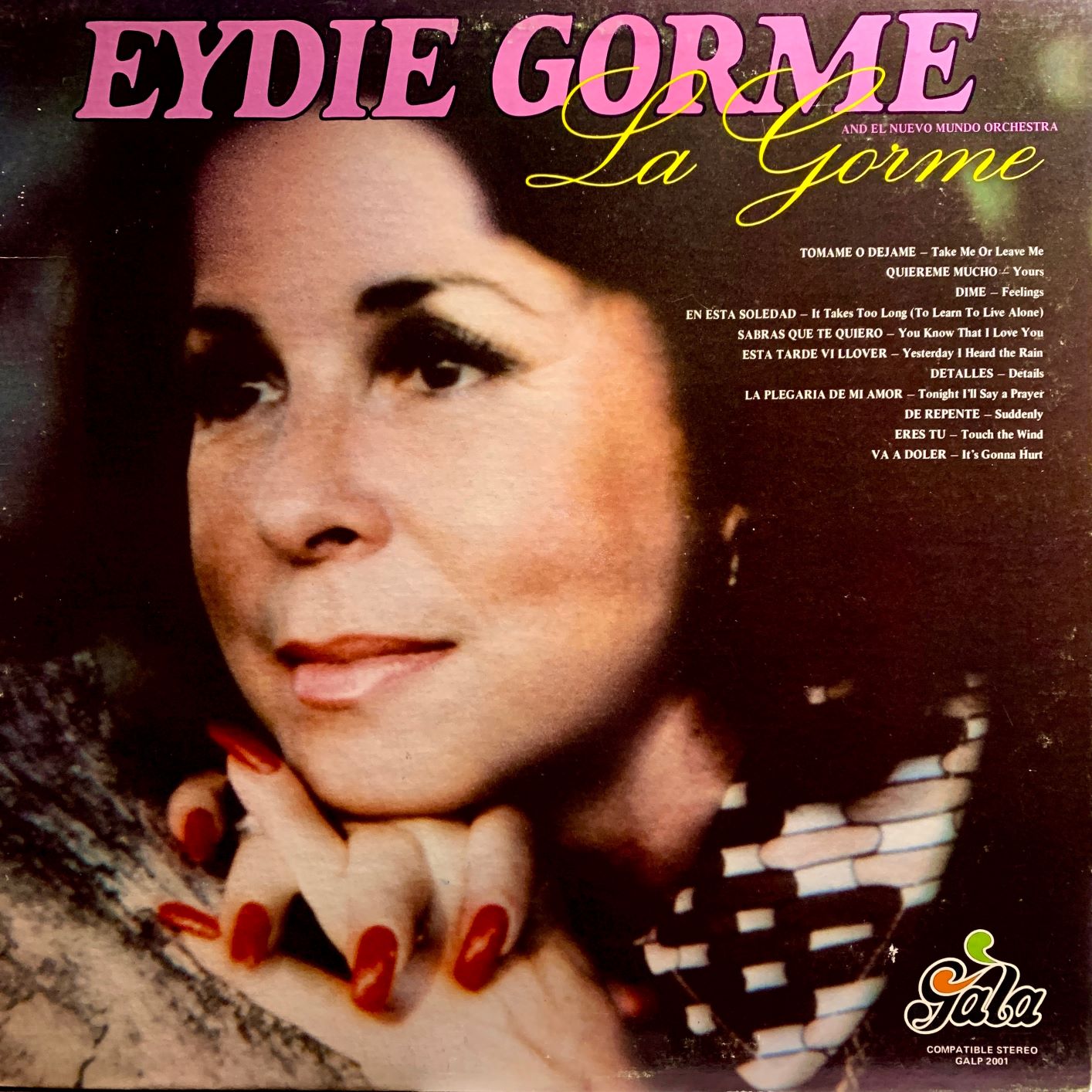

The Frontera Collection has a trove of Los Panchos discs, but not those. Gorme is also represented in the collection, although barely. There is only one recording of hers in the archive, a 45-rpm single (Gala Records GALF9001) featuring “La Plegaria De Mi Amor,” backed by the classic bolero “Quiereme Mucho.

In fact, Gorme’s polished, cosmopolitan style is the opposite of the gritty, grassroots music that Strachwitz favored, including the blues, zydeco, bluegrass, New Orleans jazz, and Tex-Mex. He dismissed more refined, middle-of-the-road material as wimpy and soulless. He even created a nickname for it that reflected his disdain. He called it “mouse music.” Hence, the title of the 2014 feature-length documentary: This Ain't No Mouse Music! The Story of Chris Strachwitz and Arhoolie Records, directed by Maureen Gosling and Chris Simon.

Of course, one man’s mouse music might be another man’s masterpiece. Which brings us to the reason for today’s topic. That solitary, scratchy single by Gorme might have easily escaped my attention had it not been for an interested fan who surfaced it from Frontera’s deep well of recorded sound.

Earlier this year, a user named Butch Tuohey posted the following message on the page for “La Plegaria De Mi Amor,” the A-side of Gorme’s Gala single:

“Hello: I have been trying to find the Spanish lyrics to this song somewhere on the web. They are not available anywhere. Do you have these lyrics, or can you let me know where I may find them? Thanks!”

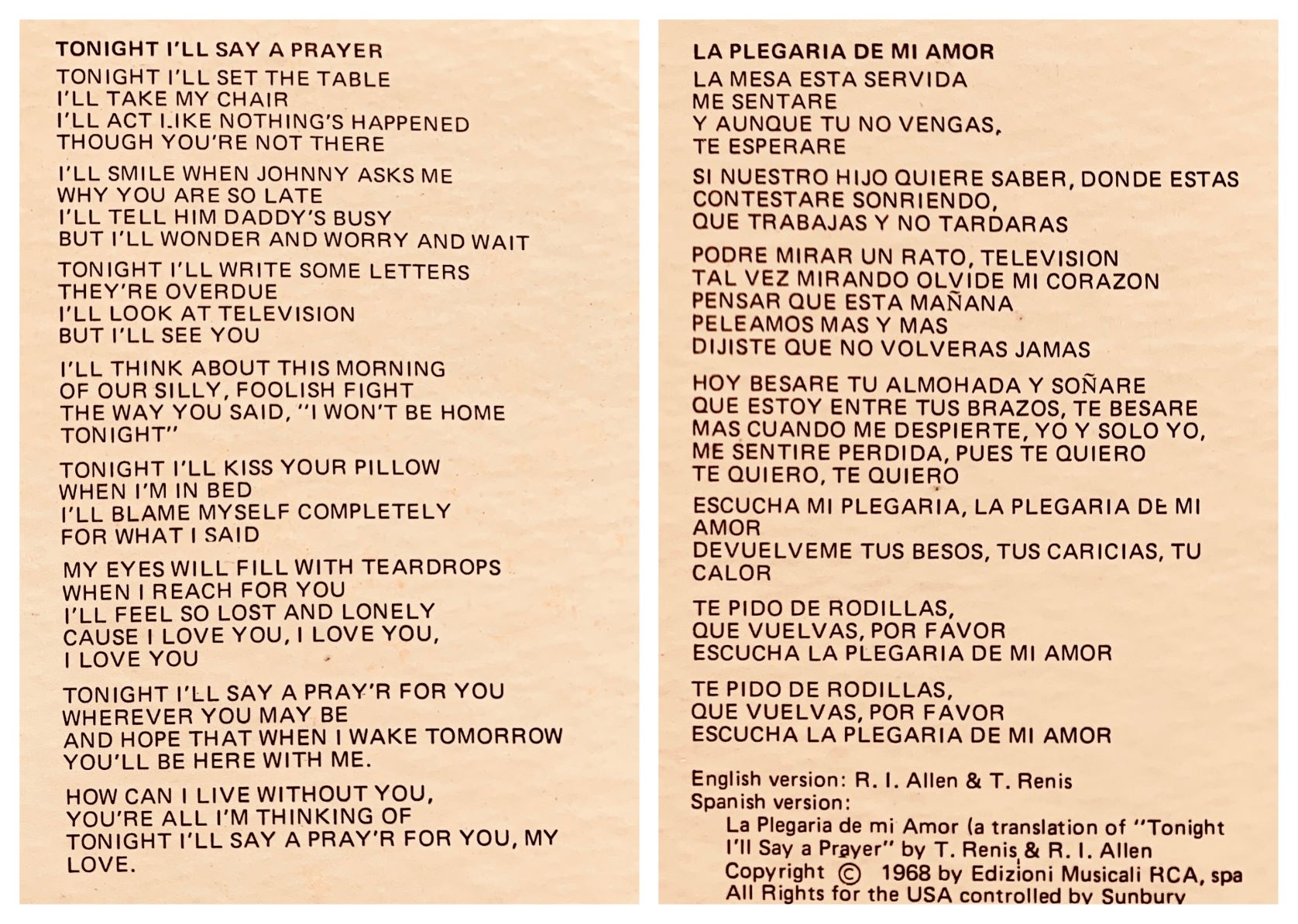

The answer is yes, you’ve come to the right place. I found the lyrics in my private record collection, as I explained to Mr. Tuohey in my response: “I happen to know the owner of the label, Gala Records, that originally released (the single) back in 1976. Like you, I could not find anything online about it. But as luck would have it, I own the original album by Eydie Gorme that includes this number. So I went to my garage and, lo and behold, the album features a gatefold cover with all the lyrics printed inside, in BOTH Spanish and English.”

The answer is yes, you’ve come to the right place. I found the lyrics in my private record collection, as I explained to Mr. Tuohey in my response: “I happen to know the owner of the label, Gala Records, that originally released (the single) back in 1976. Like you, I could not find anything online about it. But as luck would have it, I own the original album by Eydie Gorme that includes this number. So I went to my garage and, lo and behold, the album features a gatefold cover with all the lyrics printed inside, in BOTH Spanish and English.”This isn’t luck. It’s an essential part of the collector’s raison d'être, to have and hold that one rare item for when you need it. This example also speaks to the superiority of analog discs, artistically wrapped in their album covers with liner notes, lyrics, production credits, and more. Digital doesn’t compare. Original albums provide the music and, often, the story behind it.

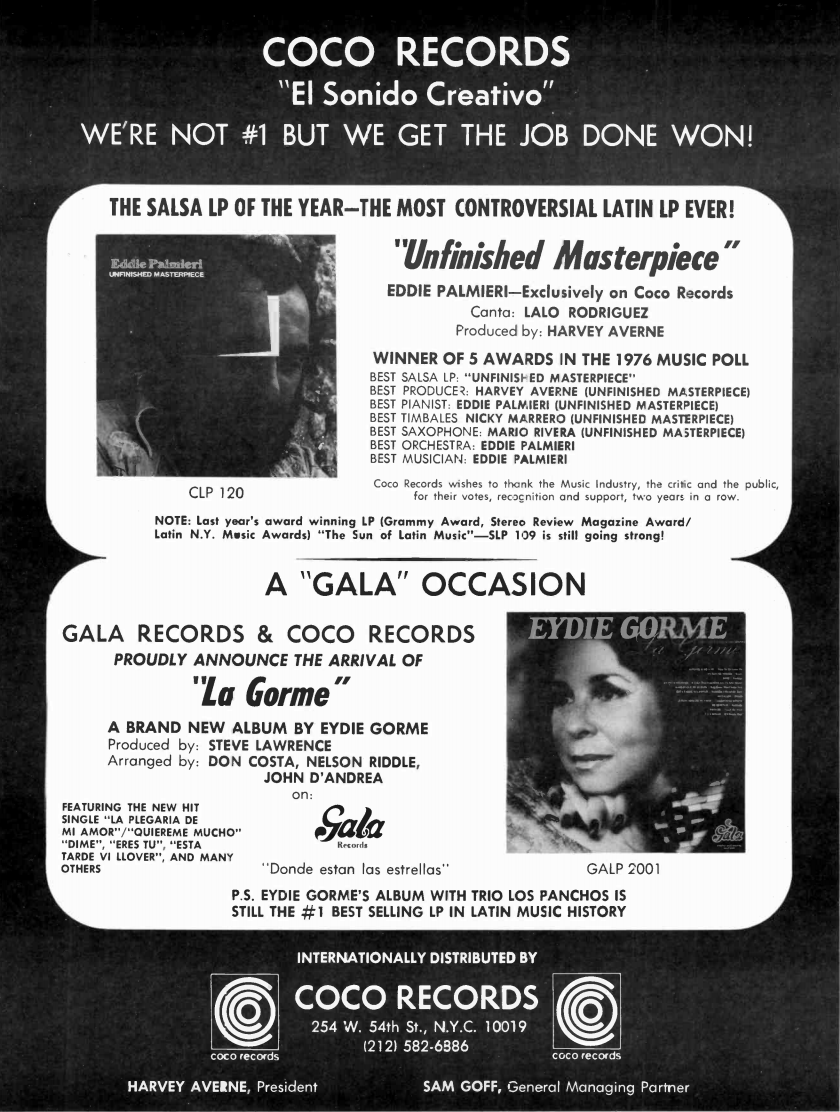

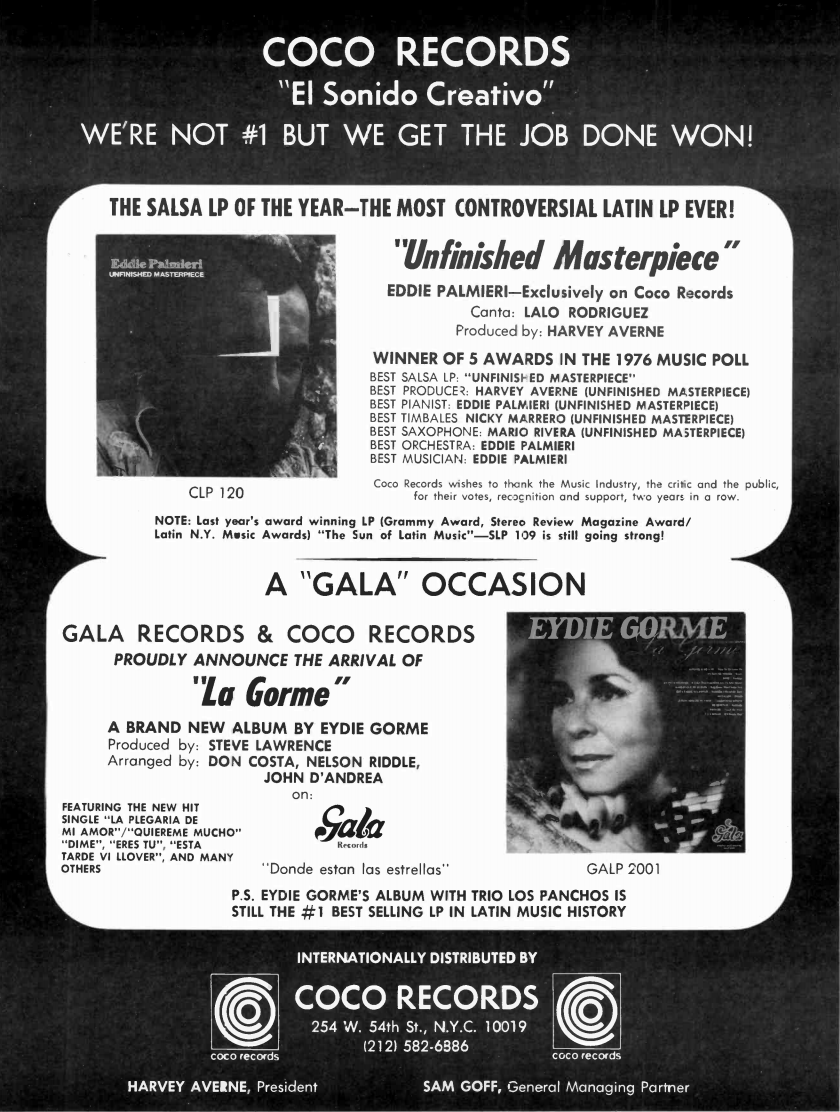

The story of this Eydie Gorme recording starts with my friend Harvey Averne, a musician, producer, and label executive from New York. We first met in the mid-1970s when he was running Coco Records, his Manhattan-based boutique label that made a splash with two Grammy-winning salsa albums by avant-garde pianist and bandleader Eddie Palmieri, which won the first two Grammy Awards ever granted for Latin music, in 1975 and 1976. In those days, I was a cub reporter for Billboard Magazine, the music trade journal based in Los Angeles, and a die-hard salsa fan.

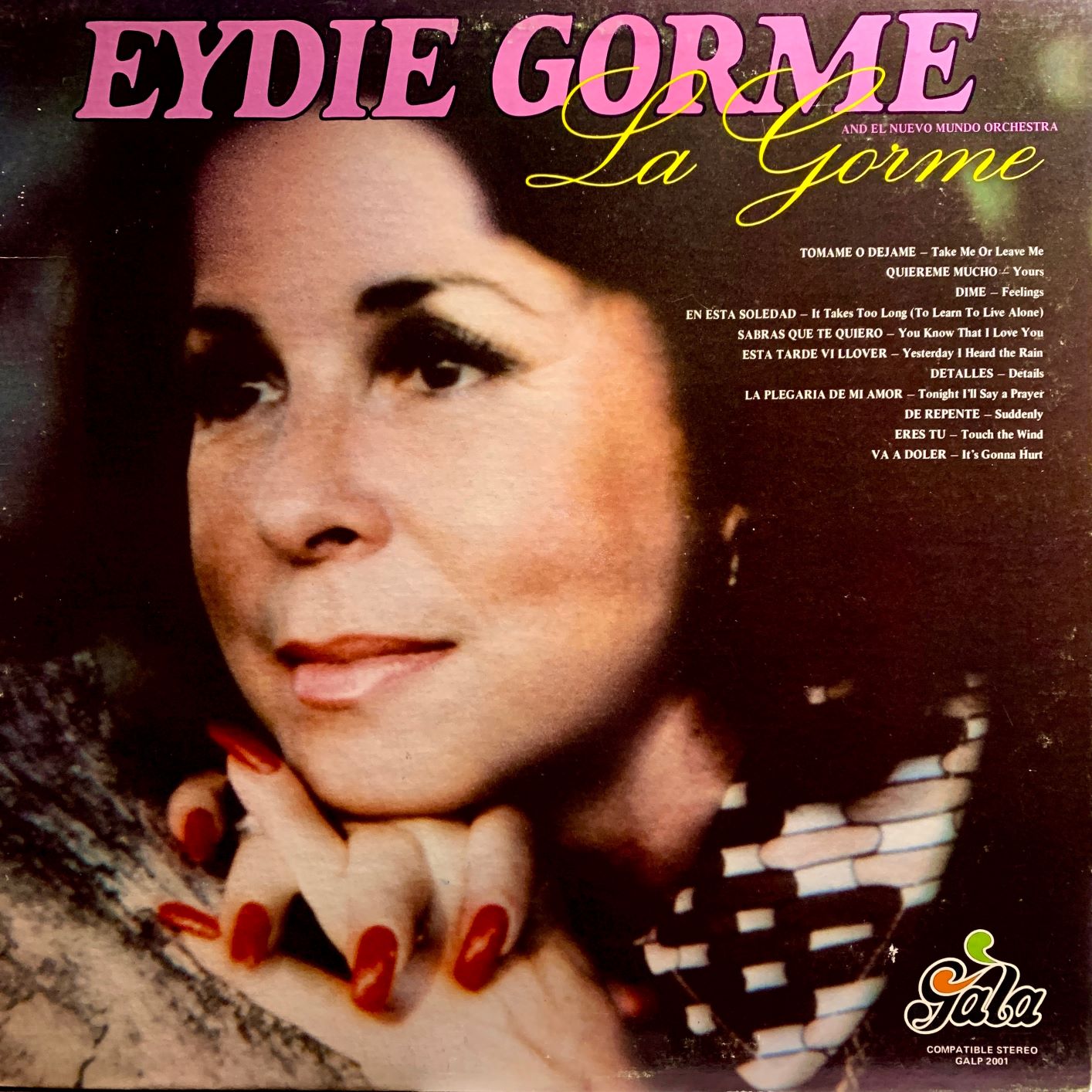

Averne, now 84, was keen to share the story of how he made the leap from hard-edged progressive salsa to the romantic, easy-listening pop of his first Gala Records LP, which was dubbed “La Gorme.” I had not formally interviewed him in more than 40 years, but he was easy to track down, since we’re friends on Facebook.

We spoke by phone in a planned half-hour interview that ran for an hour and a half. We were like two veterans swapping war stories. Yet, even after all this time, I discovered new aspects of his work with Eydie Gorme and the making of their first recording.

The singer and the producer were born in neighboring New York boroughs, eight years apart. The late Gorme (nee Edith Gormezano) was born in the Bronx to Sephardic Jewish parents who spoke Ladino at home. Averne (born Avrutsky, son of a Russian immigrant father) hailed from Brooklyn where he attended Thomas Jefferson High School with Steve Lawrence, the crooner who, in one of life’s fortuitous turns, would become Gorme’s husband and performing partner.

The singer and the producer were born in neighboring New York boroughs, eight years apart. The late Gorme (nee Edith Gormezano) was born in the Bronx to Sephardic Jewish parents who spoke Ladino at home. Averne (born Avrutsky, son of a Russian immigrant father) hailed from Brooklyn where he attended Thomas Jefferson High School with Steve Lawrence, the crooner who, in one of life’s fortuitous turns, would become Gorme’s husband and performing partner.

Steve Lawrence and Eydie Gorme were a popular singing duo in the 1950s and ‘60s who frequently appeared on television and recorded many albums together in English. In 1976, the couple was planning Gorme’s return to Latin music, following her mid-1960s peak with Los Panchos. At that same time, they got a call out of the blue from Harvey Averne, who had just seen one of their specials on television and wanted to pitch a deal.

Averne was fresh off his success with a milestone album he had produced for Eddie Palmieri, The Sun of Latin Music, which won the very first Grammy Award in the freshly minted Latin Music Category in 1975. In the business, the award was a door-opener.

Averne was fresh off his success with a milestone album he had produced for Eddie Palmieri, The Sun of Latin Music, which won the very first Grammy Award in the freshly minted Latin Music Category in 1975. In the business, the award was a door-opener.

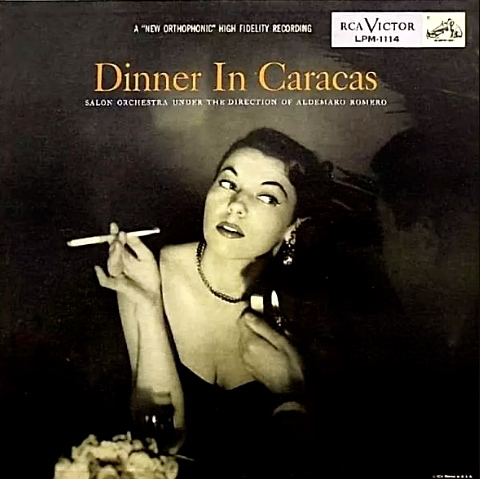

He got the meeting with Steve and Eydie at their Beverly Hills home the very next day. The independent producer, who had started his small label just four years earlier, found himself in the room with two heavyweight competitors, executives from RCA and Columbia Records. The three rivals – two Goliaths and a David – took turns making their pitches to win the business of Eydie Gorme and Gala Records, her fledgling label created for Latin music projects.

With the two other contenders in the room listening, Averne gave it his best shot.

“I don’t have the muscle that RCA and Columbia have,” he recalls saying. “But I have something they don’t have. If we work together, I have to sell Eydie Gorme records to survive. I don’t have a lot of artists, and I don’t want a lot of artists. We’d like to devote all our attention to half a dozen superstars.”

The next day, the deal was sealed.

I was surprised to learn that the first Gala release, La Gorme, was already in the can when Averne came on board. He told me that the album had been originally conceived as a collaboration between Gorme and Chilean singer Lucho Gatica, whom I profiled in a two-part biography here on the Frontera Collection blog. However, Gatica had by then entered middle-age and his splendid tenor had begun to fade.

“Lucho’s pipes were gone,” Averne says bluntly.

Nevertheless, Lucho Gatica is credited on the Gala LP as “project coordinator.” His young nephew, Humberto Gatica, who would go on to become a sought-after engineer in the music industry (Michael Jackson, Barbra Streisand, Elton John), supervised the studio work for the Gorme LP at Kendun Recorders, the fabled studio in Burbank.

That’s where Averne got to work with Don Costa, a major figure in the mid-century music business who had discovered Paul Anka and served as orchestra leader and arranger for Frank Sinatra and many other stars. Averne and Costa, who died of a heart attack in 1983, became close friends.

That’s where Averne got to work with Don Costa, a major figure in the mid-century music business who had discovered Paul Anka and served as orchestra leader and arranger for Frank Sinatra and many other stars. Averne and Costa, who died of a heart attack in 1983, became close friends.

Averne gets no artistic credit on the La Gorme LP, though his Coco Records is credited as international distributor. The album, produced by Steve Lawrence, was almost complete when Averne arrived at the Burbank studios.

“I helped button it up, but La Gorme was 90 percent finished,” he says.

Averne does take credit for finessing the studio mix to his taste, working with Costa who shared arrangement duties with Nelson Riddle, another celebrated orchestra leader, and John D’Andrea.

Specifically, Averne was not a fan of the recording style he says was used by pop stars of that era, with the vocals projecting prominently in the mix. Averne wanted more of a balance between the vocals and the orchestra.

“Everything was voice,” he says of recordings by Sinatra and others. “The orchestra was always way in the back of the mix. So I convinced them that the marriage, the balance, of the voice and the orchestra could be much closer. I want to feel every note of every instrument.”

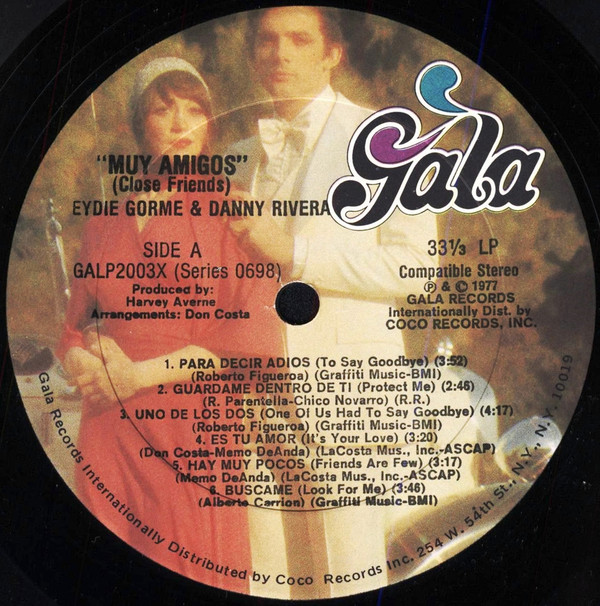

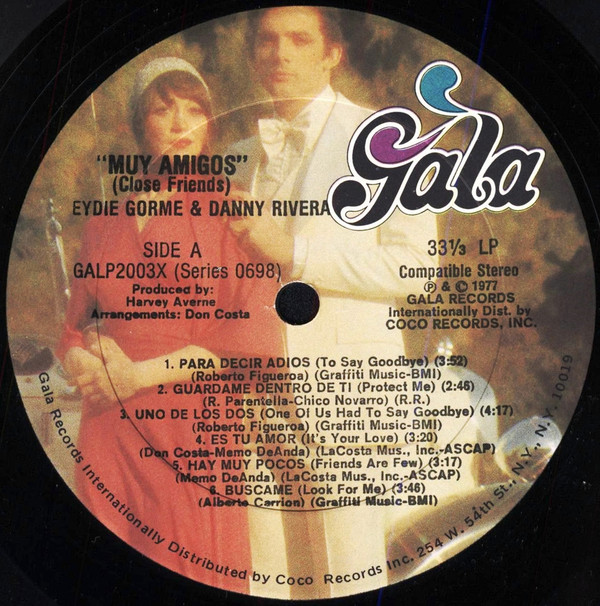

Averne’s tinkering with the sound was limited to a couple of unfinished tracks. But he was able to apply his studio strategy more fully as producer of the label’s follow-up recording, Muy Amigos / Close Friends, an unlikely collaboration he conceived between Gorme and Puerto Rican singer Danny Rivera that yielded the smash duet “Para Decir Adios.” Released in 1977, the album was arranged and conducted by Don Costa, who also co-wrote five of ten tracks, and mixed by Averne at the same Kendun Recorders.

(Musical Trivia: Averne says he convinced a reticent Costa to perform on the album, something the famed arranger had not done for decades, although he had started his career as a session musician in the late 1940s. Without notice, Costa arrived in the studio with his guitar the next day, ordered the engineer to cue up “Para Decir Adios,” and spontaneously overdubbed the song’s Spanish guitar intro to the already finished recording, "And he never played again," Averne asserts.)

(Musical Trivia: Averne says he convinced a reticent Costa to perform on the album, something the famed arranger had not done for decades, although he had started his career as a session musician in the late 1940s. Without notice, Costa arrived in the studio with his guitar the next day, ordered the engineer to cue up “Para Decir Adios,” and spontaneously overdubbed the song’s Spanish guitar intro to the already finished recording, "And he never played again," Averne asserts.)

Costa had also arranged several tracks from Gorme’s inaugural Gala album, including “La Plegaria de Mi Amor,” the song for which the Frontera user requested lyrics. As it turns out, the tune had a trail of translations that required some backtracking, from Spanish to English and finally the Italian original.

The song is based on an Italian composition entitled “Il Posto Mio” (My Place), with lyrics by Alberto Testa and music by Tony Renis, who debuted the number in February 1968 at the 18th annual Sanremo Music Festival (Festival di Sanremo), a live competition featuring previously unreleased songs. Since then it has been covered by more than a dozen artists, including an instrumental version by jazz vibraphonist Lionel Hampton who also appeared on the festival stage that year in Sanremo, a coastal city in northern Italy, about an hour east of Nice, France.

Two years later, Gorme recorded her solo rendition of the song in English, “Tonight I’ll Say a Prayer,” which served as the title song of her 1970 LP on RCA. The English version was penned by American pop composer Robert I. Allen, whose other credits include hits by major stars such as Dean Martin, Tony Bennett, Perry Como, and Sarah Vaughn.

The English lyrics have a different tone and meaning than the Italian original. Allen’s verses are a plea from a wounded wife and mother longing for her husband’s return following a marital spat. The Spanish version recorded six years later by Gorme faithfully traces Allen’s sad story, but the album credits do not name the translator.

In the end, it’s fascinating how a fan’s simple inquiry about a marginal database entry can lead to a musical journey across decades and continents. It goes to show that, despite its name, the Frontera Collection really has no boundaries.

– Agustín Gurza

Tags

Images