Featured Song: 'Perfidia' and the Transcendent Beauty of the Bolero

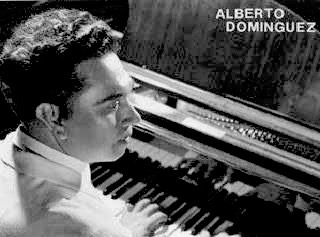

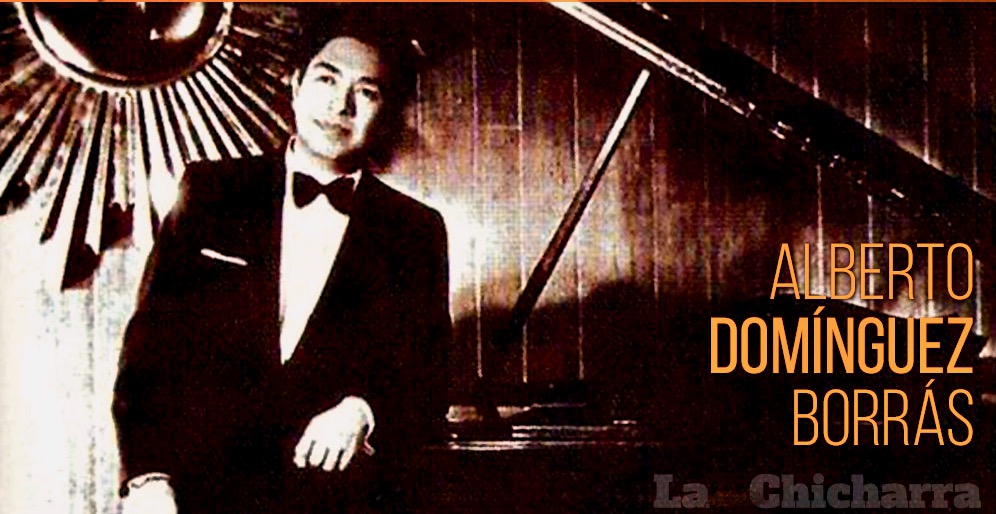

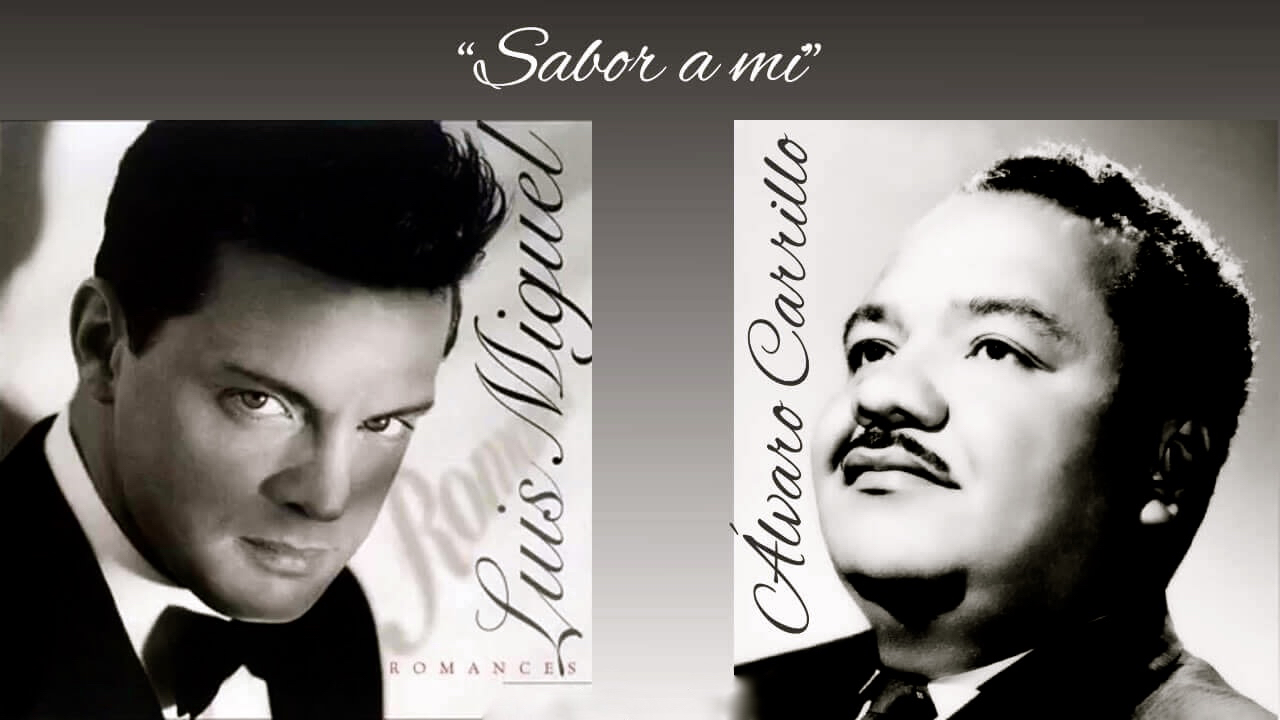

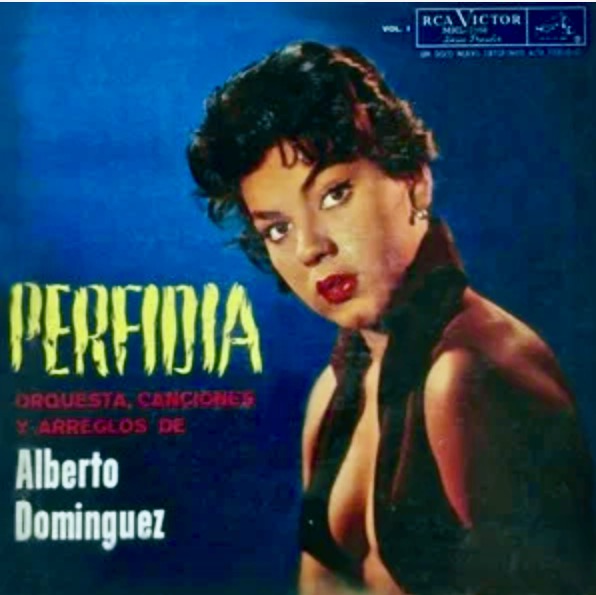

“Perfidia” has stood as one of the most cherished and enduring songs in the Latin American songbook. Composed more than 80 years ago by Mexico’s Alberto Dominguez, it is enshrined as one of those timeless standards that continues to inspire artists and resonate with music lovers, young and old.

“Perfidia” has stood as one of the most cherished and enduring songs in the Latin American songbook. Composed more than 80 years ago by Mexico’s Alberto Dominguez, it is enshrined as one of those timeless standards that continues to inspire artists and resonate with music lovers, young and old.

Recently, I heard the song’s memorable melody which watching a new movie on Netflix, the Spanish film Vivir Dos Veces (2019), by Barcelona-born director Maria Ripoll. The movie is about an aging math professor named Emilio, a lonely widower who finds himself sinking into the terrifying early stages of dementia. It explores how he and his small family, a take-charge daughter and precocious granddaughter, handle the crisis.

The more Emilio’s faculties slip away, the more he obsesses over the memory of a childhood infatuation. He drifts off into gauzy, sun-dappled flashbacks of casual encounters between him as a geeky, awkward boy and her, the lovely, vibrant young girl of his dreams. The classic bolero infiltrates his memories and floats through the film, infusing it with those emotional qualities that characterize so many of these old romantic songs – an almost immobilizing nostalgia, deep yearning for an unrequited love, and the aching sense of loss for what might have been.

The movie’s narrative revolves around Emilio’s seemingly quixotic quest to find and reconnect with the girl that still sparks his tantalizing memories, and awakens his undying need for true love.

“Perfidia” was a perfect song choice for the film’s themes of loss and longing. The original Spanish lyrics were also written by Dominguez, born Alberto Domínguez Borrás on Cinco de Mayo of 1906. He was part of a huge family (18 siblings!) from the charming, indigenous town of San Cristóbal de las Casas, one of Mexico’s so-called “pueblos mágicos,” located in the state of Chiapas.

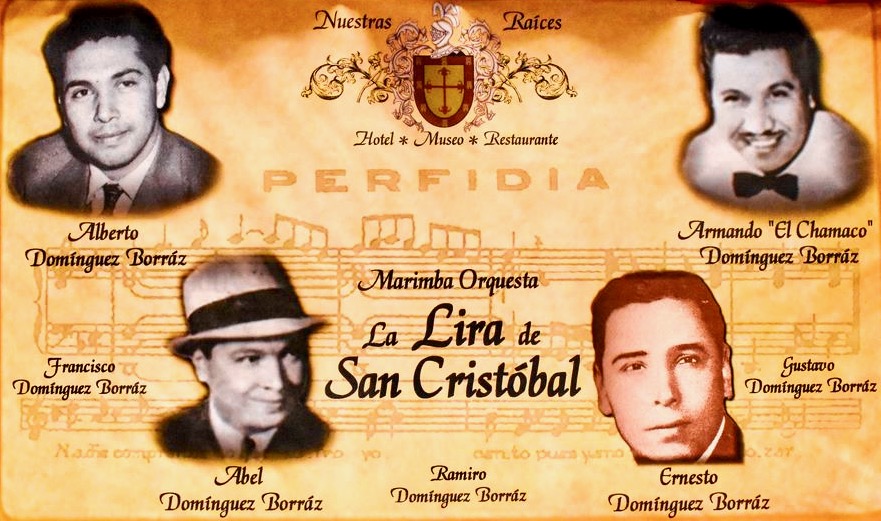

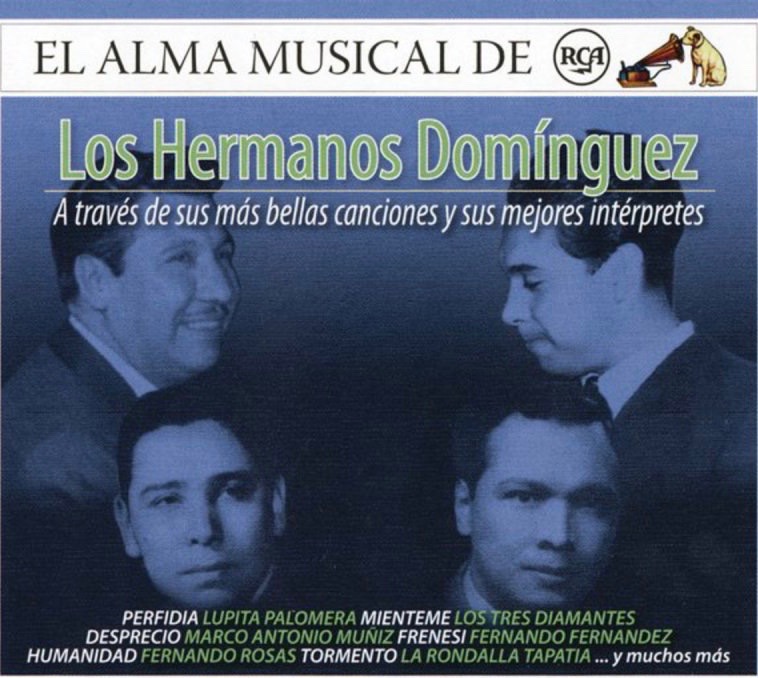

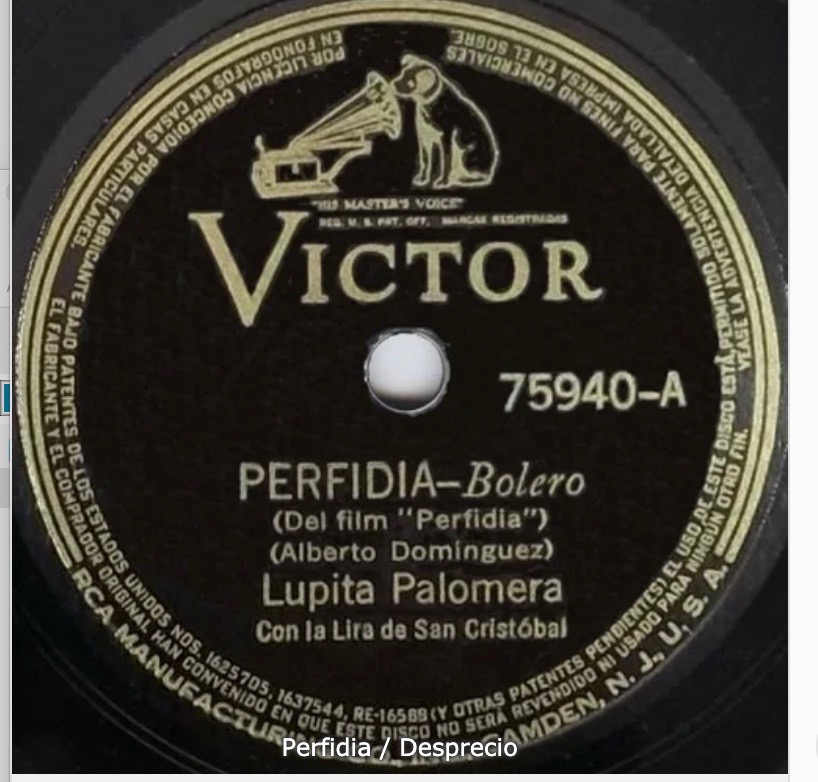

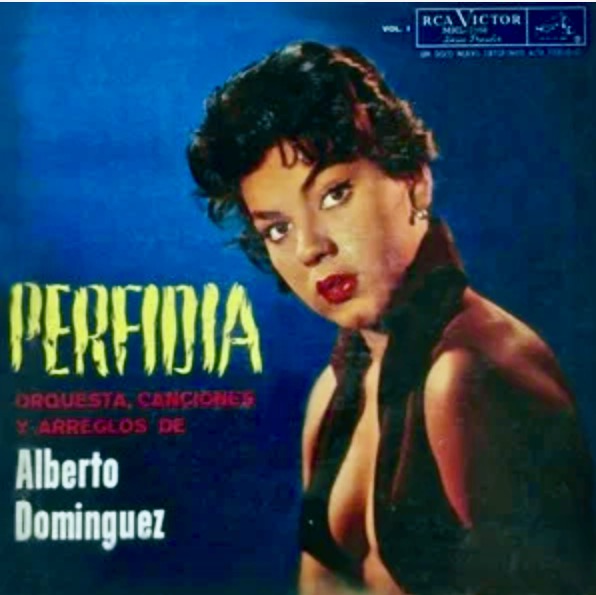

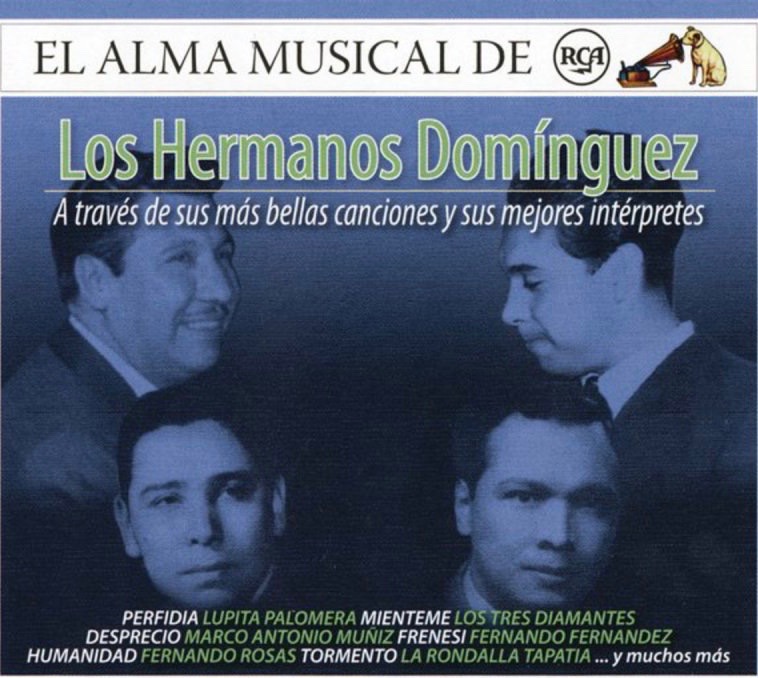

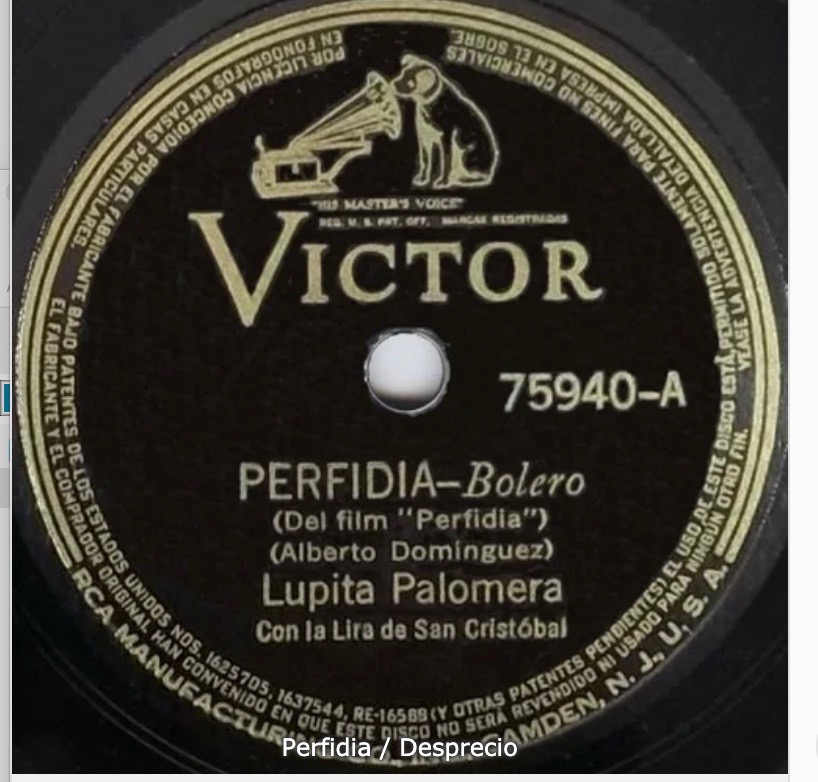

They were a talented clan, gaining early celebrity as Los Hermanos Dominguez. While still in their teens, several of the brothers formed a marimba orchestra known as La Lira de San Cristóbal, which would go on to record for RCA Victor. In addition to Alberto, three of the brothers also became composers credited with scores of romantic songs: Abel (“Óyelo Bien,” “Tormento”), Ernesto (“Adiós en el Puerto” “Buganbilia”) and Armando, known as El Chamaco Dominguez (“Miénteme,” “Sin Saber Porqué”).

They were a talented clan, gaining early celebrity as Los Hermanos Dominguez. While still in their teens, several of the brothers formed a marimba orchestra known as La Lira de San Cristóbal, which would go on to record for RCA Victor. In addition to Alberto, three of the brothers also became composers credited with scores of romantic songs: Abel (“Óyelo Bien,” “Tormento”), Ernesto (“Adiós en el Puerto” “Buganbilia”) and Armando, known as El Chamaco Dominguez (“Miénteme,” “Sin Saber Porqué”).

But it was Alberto who enjoyed the most success, propelled by two early compositions – “Perfidia” and “Frenesí.” Released almost back to back, they became popular around the world. By the time he was 35, he had skyrocketed to international fame with these two beloved songs, both destined to become classics. During the 1930s and ‘40s, he made frequent trips to the United States, Europe, and the Caribbean, staying outside of Mexico for years at a time. During his life, he amassed a repertoire of 366 compositions, according to the Mexican composers society Sociedad de Autores y Compositores de México (SACM), of which he was co-founder in his youth and vice-president at the time of his death in 1975 at age 69.

“Perfidia” made its debut on the silver screen in a film of the same name, also released in Mexico in 1939, and in the U.S. the following year. Filmmakers would continue to feature the melody in their work over the coming decades. In the 1941 film, Father Takes a Wife, a young and dapper Desi Arnaz breaks into the chorus of “Perfidia” to spontaneously serenade an obviously impressed, though just married Gloria Swanson on her honeymoon on the deck of a ship. The following year, in the 1942 noir classic Casablanca, “Perfidia” plays while the characters Rick and Ilsa (Ingrid Bergman and Humphrey Bogart) dance cheek-to-cheek in the famous Paris flashback sequence. Fifty years later, a version sung by Linda Ronstadt is featured in the soundtrack to the 1992 film, The Mambo Kings, starring Antonio Banderas. (The composer’s other classic, “Frenesí,” was also used in its share of renowned movies, including two Oscar winners: Woody Allen’s Radio Days (1987) and Martin Scorsese’s Raging Bull (1980), with Robert de Niro.)

“Perfidia” made its debut on the silver screen in a film of the same name, also released in Mexico in 1939, and in the U.S. the following year. Filmmakers would continue to feature the melody in their work over the coming decades. In the 1941 film, Father Takes a Wife, a young and dapper Desi Arnaz breaks into the chorus of “Perfidia” to spontaneously serenade an obviously impressed, though just married Gloria Swanson on her honeymoon on the deck of a ship. The following year, in the 1942 noir classic Casablanca, “Perfidia” plays while the characters Rick and Ilsa (Ingrid Bergman and Humphrey Bogart) dance cheek-to-cheek in the famous Paris flashback sequence. Fifty years later, a version sung by Linda Ronstadt is featured in the soundtrack to the 1992 film, The Mambo Kings, starring Antonio Banderas. (The composer’s other classic, “Frenesí,” was also used in its share of renowned movies, including two Oscar winners: Woody Allen’s Radio Days (1987) and Martin Scorsese’s Raging Bull (1980), with Robert de Niro.)

In Vivir Dos Veces, an exploration of the ravages of Alzheimer’s disease, the soundtrack’s haunting rendition is performed in a wistful, whispering voice by Maria Rodés, a singer/songwriter who’s also from Barcelona. Unlike past orchestral arrangements of the song with dramatic vocals, Rodés offers a spare, restrained rendition with a tinkling piano accompaniment.The movie itself – known by its English title as Live Twice, Love Once – got mixed reviews on Rotten Tomatoes, with only half of the critics giving it thumbs up. It fared better with moviegoers, with almost 80 percent giving it a fresh rating. The disapproving critics called it “predictable” and “unforgettable,” with “comedic and romantic payoffs (that) are limp.”

By contrast, consider some glowing comments (in Spanish) from people who saw the film and were inspired to seek out the theme song on YouTube:

“I came here to cry with the song after having cried with the movie.”

“I watched the film with a lump in my throat remembering the only true love I ever had. There are a lot of versions of this song, but this one goes straight to the heart.”

“I grew up listening to this song in the voice of my aunt, who suffered from senile dementia and died ten years ago. She forgot everything, except how to sing.”

These comments left me wondering about the impact of the song itself, which figures so prominently throughout the drama, on the reactions, pro or con, of individual movie-goers. “Perfidia” is one of those old boleros that gets under your skin at an early age, a melody that gets in the bloodstream, a lyric that lodges latent in memory, retrievable at any age. Maybe one likes the movie better if the song awakens those recuerdos, evokes that nostalgia, renews that romanticism.

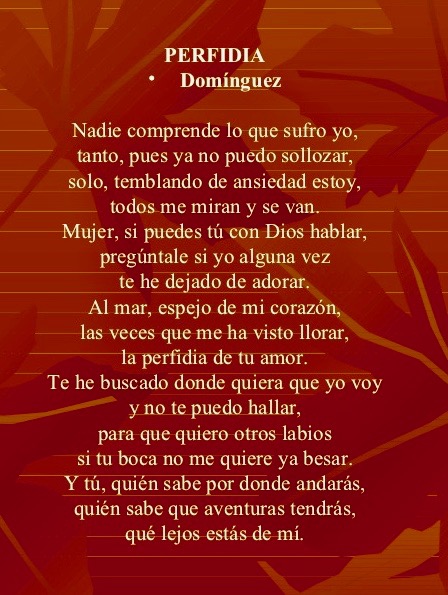

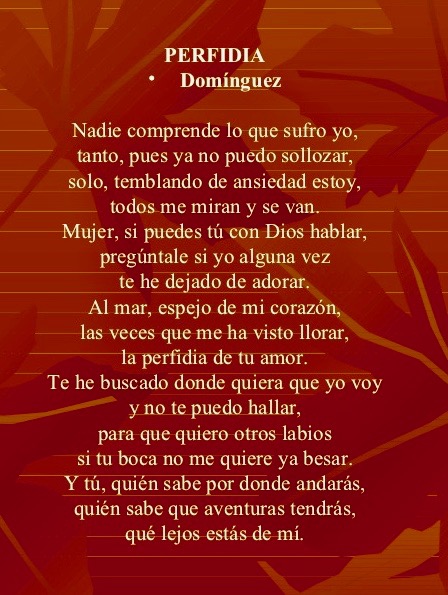

In Spanish, the lyrics conjure up a state of darkness and despair, part of a style known colloquially as “canciones corta-venas,” or songs to slit your wrists by. It describes a man so consumed by heartbreak and sorrow that people don’t want to be around him. "Perfidia," which literally means perfidy, is often translated as treachery or betrayal. But the song never actually says the woman cheated, or explains why she left. The man torments himself wondering where she may be and what adventures she may be having. Only God and the sea know the depths of his love and pain, he tells her.

In Spanish, the lyrics conjure up a state of darkness and despair, part of a style known colloquially as “canciones corta-venas,” or songs to slit your wrists by. It describes a man so consumed by heartbreak and sorrow that people don’t want to be around him. "Perfidia," which literally means perfidy, is often translated as treachery or betrayal. But the song never actually says the woman cheated, or explains why she left. The man torments himself wondering where she may be and what adventures she may be having. Only God and the sea know the depths of his love and pain, he tells her.

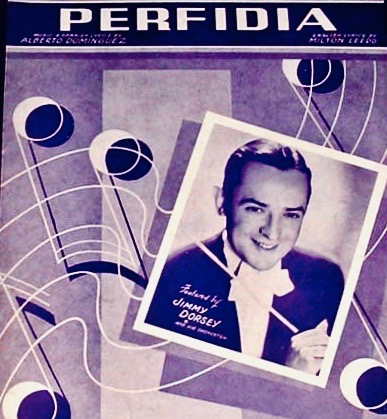

There are two versions in English, but they both lack the emotional power of the original. The most well-known is by Milton Leeds, born in Omaha, Nebraska, three years after his Mexican counterpart. It is more corny than “corta-venas.”

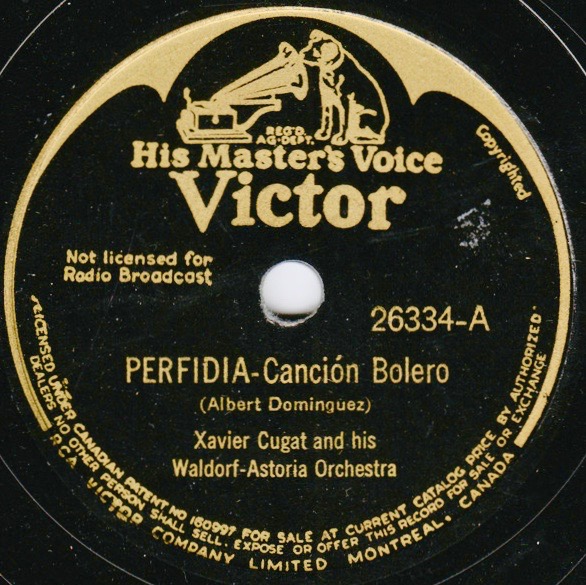

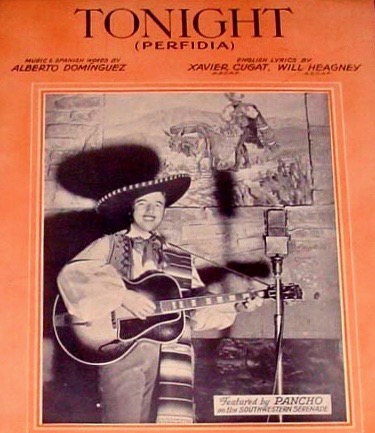

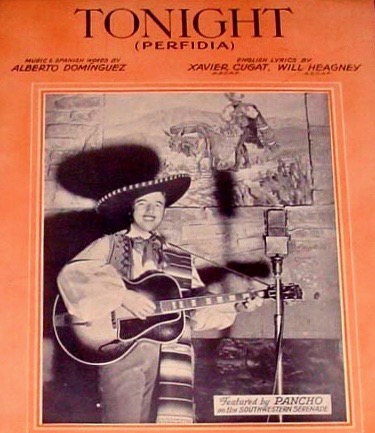

A more obscure version, published in 1939 under the title “Tonight,” is an old-fashioned love song credited to bandleader Xavier Cugat and Will Heagney, a successful songwriter and vaudevillian. Cugat had an early hit with “Perfidia” the following year, but as an instrumental. Ten years later, crooner Tony Martin recorded a bilingual version of “Tonight,” using the Cugat/Heagney lyrics. These English verses are much more graceful and literate than the Leeds rendition, although they also lack the element of deep sorrow and desperate loss.

A more obscure version, published in 1939 under the title “Tonight,” is an old-fashioned love song credited to bandleader Xavier Cugat and Will Heagney, a successful songwriter and vaudevillian. Cugat had an early hit with “Perfidia” the following year, but as an instrumental. Ten years later, crooner Tony Martin recorded a bilingual version of “Tonight,” using the Cugat/Heagney lyrics. These English verses are much more graceful and literate than the Leeds rendition, although they also lack the element of deep sorrow and desperate loss.

There are scores of recordings of this classic song, in both languages. I have more than 100 counted so far in my private collection. But I was still amazed at the wide variety of artists who have waxed the song over the years. There are versions in myriad styles, including bolero, jazz, rock, and cha cha cha. “Perfidia” was even performed a cappella in 1941 by a then-fledgling vocal group at Princeton University named the Nassoons, which to this day uses the Mexican composition as its signature song.

There are scores of recordings of this classic song, in both languages. I have more than 100 counted so far in my private collection. But I was still amazed at the wide variety of artists who have waxed the song over the years. There are versions in myriad styles, including bolero, jazz, rock, and cha cha cha. “Perfidia” was even performed a cappella in 1941 by a then-fledgling vocal group at Princeton University named the Nassoons, which to this day uses the Mexican composition as its signature song.

“Perfidia,” like “Bésame Mucho,” “Malagueña,” and many other Latin American standards, were popular among American audiences through the first half of the 20th century. The Spanish-language songs were completely integrated into the fabric of the music scene in the United States, part of the standard repertoire of many major artists.

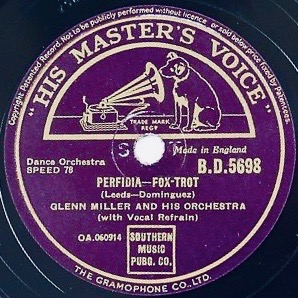

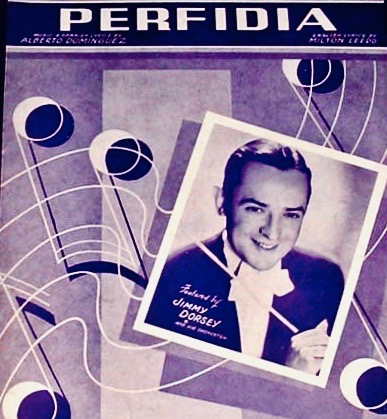

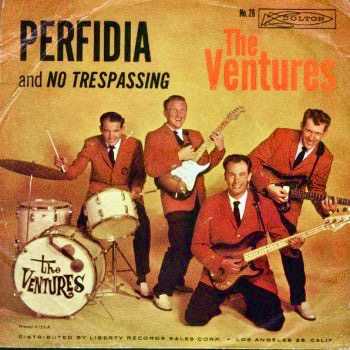

There were vocal versions of “Perfidia” by crooners Nat King Cole, Mel Tormé, and Julie London. Easy listening renditions by the orchestras of Lawrence Welk, Ray Conniff, and Percy Faith. Dance arrangements by the big bands of Glenn Miller, Benny Goodman, and the Dorsey brothers. Jazz interpretations by Charlie Parker, Dave Brubeck, and Manu Dibango. In 1960, the Ventures released a surf-rock version of "Perfidia," a twangy guitar instrumental that peaked at No. 15 on the Billboard Hot 100.

Not all versions hit the right note. A Swiss rockabilly band named Hillbilly Moon Explosion recorded a quirky, bilingual take of the tune in 2013. Tex-Mex singer Trini Lopez gave the song a dreadful, trivial pop treatment that makes it sound childish. And the popular vocal group The Four Aces harmonized on a finger-snapping rendition that’s a throwback to the 1940s swing era.

Not all versions hit the right note. A Swiss rockabilly band named Hillbilly Moon Explosion recorded a quirky, bilingual take of the tune in 2013. Tex-Mex singer Trini Lopez gave the song a dreadful, trivial pop treatment that makes it sound childish. And the popular vocal group The Four Aces harmonized on a finger-snapping rendition that’s a throwback to the 1940s swing era.

The song was also recorded by artists around the globe, such as Cuba’s Issac Delgado and Ibrahim Ferrer, Venezuela’s Alfredo Sadel, as well as European performers Nana Mouskouri (Greece), Andrea Bocelli (Italy), and Paco de Lucía (Spain).

Of course, since its inception it has also had countless interpreters in its native country. There are Mexican versions by crooners of all eras, including Elvira Ríos, Javier Solís, and Luis Miguel. By guitar trios, such as Los Tres Caballeros and Los Panchos. The song was even adapted by Mexico’s acclaimed alt-Latino band, Café Tacuba, released on its 1996 album, “Avalancha de Éxitos.” Across the border, U.S. Latin artists also got into the act, including Freddy Fender, Eydie Gorme, René Touzet, and the aforementioned Linda Ronstadt.

The earliest recordings of the song were also made by Mexican artists, although there is some debate about who was first. Two notable versions were released on the Victor label in 1939, the year the song was published. Singer Lupita Palomera delivered a heartfelt but elegant performance, released as a 10-inch single backed by none other than the Lira de San Cristóbal, of the Hermanos Dominguez. The image posted with this YouTube video displays the date 1937 in large type on the record label, although it’s almost certainly wrong and is definitely altered because release dates, when cited by record companies, always appeared in much smaller type. The other version recorded in 1939 is by Mexican crooner Juan Arvizú. It was also a Victor 10-inch single, recorded in Buenos Aires in October, and released the following year.

The earliest recordings of the song were also made by Mexican artists, although there is some debate about who was first. Two notable versions were released on the Victor label in 1939, the year the song was published. Singer Lupita Palomera delivered a heartfelt but elegant performance, released as a 10-inch single backed by none other than the Lira de San Cristóbal, of the Hermanos Dominguez. The image posted with this YouTube video displays the date 1937 in large type on the record label, although it’s almost certainly wrong and is definitely altered because release dates, when cited by record companies, always appeared in much smaller type. The other version recorded in 1939 is by Mexican crooner Juan Arvizú. It was also a Victor 10-inch single, recorded in Buenos Aires in October, and released the following year.

The Arvizú recording is one of about a dozen versions contained in The Frontera Collection, almost all 78s. Following are brief reviews of some of those recordings, which also represent a wide variety of styles:

- Juan Arvizú (Victor 83748)

Born in 1900 in the colonial city of Querétaro, Arvizú was part of that early cohort of male singing stars – Jorge Negrete, Pedro Vargas, José Mojica, Alfonso Ortiz Tirado, Pedro Infante – that dominated the early years of the nation’s recording industry. He is credited with discovering a young pianist and composer who accompanied the singer in the early years and emerged as a towering figure in Mexican pop music of the mid 1900s. His name was Agustín Lara. Arvizú’s exquisite version of “Perfidia” was recorded in New York on April 17, 1939, with the accompaniment of the Marimba Pan-Americana, featuring two marimbas played by five musicians. This is a truly sensitive and sophisticated rendition, riding on the singer’s range, control, and finesse. Listen to the high final note that he holds, as if from a cloud, and you’ll see why he earned the nickname El Tenor de la Voz de Seda.

- Pedro Vargas (Victor 76074)

The smooth, honeyed tenor of the operatically trained Pedro Vargas caresses the lyrics of this classic bolero. Vargas (1906-1989), who later gained fame as a ranchero singer, started his career as a cosmopolitan crooner with early success in Latin American recording capitals, from Havana to Buenos Aires. He displays masterful control and phrasing, without letting technique diminish the feelings of sadness and loss. The arrangement is meticulously tailored, at first restrained behind his vocals, then blossoming during the instrumental break, coming to a very soft landing. The label indicates the song is from the movie, with accompaniment by the accomplished Cuban group, Orquesta Havana – Riverside (not to be confused with Havana Cosmopolitan discussed below). The orchestra has featured some of Cuba’s top musicians, accounting for its polished and professional sound.

- Pérez Prado (Victor LPM-1459)

This is a stark example of how a distinctive musical style is not well-suited for all songs. Pérez Prado, crowned El Rey del Mambo, had big hits in the US with his crossover Cuban music, especially high-energy numbers like Mambo No. 5. The bandleader helped popularize Latin dance music, with a brash, bombastic sound, and a showy stage style. On this lovely bolero, however, the Prado sound works against the feeling. The horn section is too cute and bouncy to convey the misery of being left in the dark by the one you love. It makes the arrangement, included here on an RCA 33-rpm album, sound corny and gimmicky. To paraphrase the bandleader’s signature exclamation: “Ugh!”

- Xavier Cugat (Victor 26334)

This is a lush and polished arrangement that evokes the era of big-bands and elegant ballrooms. Though the label doesn’t specify, the rich arrangement was likely written by Cugat, a trained violinist who was born in Spain and grew up in Cuba. After coming to the U.S., the flamboyant bandleader found national celebrity as he helped introduce Americans to Latin dance styles, especially the tango, mambo, and cha cha cha. According to the Discography of American Historical Recordings, Cugat first recorded “Perfidia” in 1939 with the Waldorf-Astoria Orchestra (named for the famed New York hotel), which Cugat directed for approximately 16 years, starting in 1933. It soon became a big hit for the band. Cugat’s instrumental performance is highly refined, with piano, percussion, violins, marimbas, guitar, and muted trumpets interlacing their parts in textured layers. It may be considered “easy listening” (the soft, mood music of the pre-rock era), but it is by no means easy to make music at this level. It is lovely and timeless.

- Javier Solis (Columbia ES-1728)

Taken from an album of Latin standards titled “Javier Solís en New York,” this track was recorded by the Mexican singing star during a tour of the United States. The international repertoire, and the dapper fedora he wears in the cover photo, signal a departure for Solís, who gained famed as a mariachi singer. The delicate arrangement by orchestra director Chuck Anderson seems perfectly tailored to Solís’s breathy and sensuous vocals, punctuated with his trademark bursts of power and passion. That stylistic duality, between country and cosmopolitan, would define the rest of his short career. The so-called “Rey del Bolero Ranchero” died in 1966, just six years after recording his mournful version of this sad song. He was just 34.

- Los Violines De America (ARV Records, ARVLP-1010)

Although released on a Texas-based label that was part of the legendary House of Falcon, this instrumental recording was licensed from Discos Virrey in Lima, Peru, where it was produced. It’s actually a medley of two songs that starts with another Lain standard, “Siempre en Mi Corazón” (Always in My Heart), written in 1942 by world-renowned Cuban composer Ernesto Lecuona. Like “Perfidia,” which completes the medley, Lecuona’s tune was also translated to English (by Kim Gannon) and featured in a film of the same title, Always in My Heart (1942), earning an Oscar nomination for Best Original Song. The two pieces merge well together in this arrangement featuring occasional accordion touches. This is easy listening par excellence, what some condescendingly call elevator music. Think Lawrence Welk, and you will see the champagne bubbles float before your eyes.

- Orquesta Havana Cosmopolitan (Coast Records 7006)

This standard instrumental version adds nothing new nor special to the song’s interpretation. The arrangement is pedestrian and the musicianship is just competent. It makes you wonder about the origins of the orchestra, which sounds neither cosmopolitan nor habanera. I searched diligently for information, but found only one reference to the band on a Chicago-based music website, Wholesome, by a blogger who was equally stumped. This group “is basically a mystery,” he writes in reviewing the orchestra’s recording of “Bruca Maniguá,” the flip side of “Perfidia” on the Los Angeles-based Coast label. “It may, or may not, have been recorded in Cuba,” the blogger continues, adding that “the band also had a 78 on the Mexican Peerless label.” He liked the band’s performance – “quite beautiful and powerful!” – a lot more than I did.

- Antonio Vera (Decca 21032A)

This orchestral version was also recorded in New York in 1939, according to Richard K. Spottswood’s discography, Ethnic Music on Records. It was part of a July 20 Decca session with Vera’s orchestra that included a total of six songs – four boleros, a conga, and a rumba – all featuring vocalist López Prado. Vera (1929-1996) was a famed Cuban composer who wrote dozens of songs with his longtime composing partner Giraldo Piloto, famously credited as the writing team of Piloto y Vera. Vera’s version of “Perfidia” has a distinct, yet subtle tropical feel, with violin accents throughout that are quite unusual. As expected of an accomplished Cuban group, the musicianship is superb, and the tender tenor closes the number with a sustained flourish.

– Agustín Gurza

Blog Category

Tags

Images