Featured Song: Romance and Revolution in “Sabor a Mí”

Among acculturated Mexican Americans, only a handful of Mexican songs have managed to gain wide popularity and a special cultural significance on this side of the border. A few become iconic songs, with lyrics and melodies memorized by the children and grandchildren of immigrants.

Among acculturated Mexican Americans, only a handful of Mexican songs have managed to gain wide popularity and a special cultural significance on this side of the border. A few become iconic songs, with lyrics and melodies memorized by the children and grandchildren of immigrants.

One of them, of course, is “La Bamba,” the traditional jarocho tune turned into a 1950s rock hit by Ritchie Valens, and later reprised by Los Lobos for the 1987 biopic of the teenaged Chicano singer from Pacoima, California. Another is “El Rey,” the mariachi classic by Jose Alfredo Jimenez, about a spurned, penniless vagabond who clings to his overblown pride and capricious ways, a monarch in his own mind.

There is only one song, however, that is so embedded in the bicultural community that it’s been dubbed the Chicano National Anthem. Surprisingly, it’s not a rousing number that stirs some sense of ethnic pride. It’s a beautiful yet sorrowful torch song about the lingering traces of a lost love: “Sabor a Mí.”

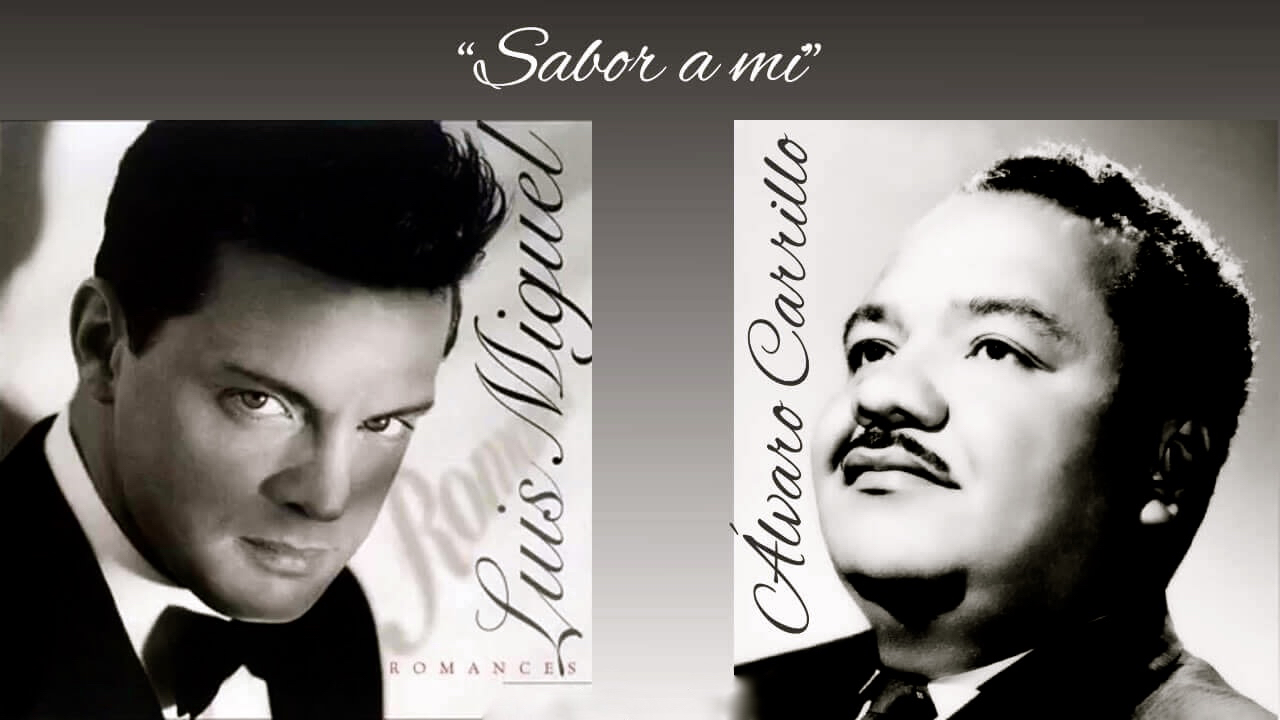

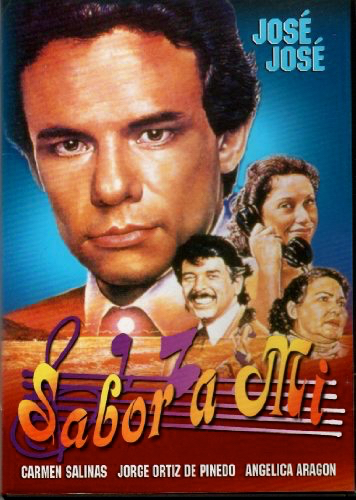

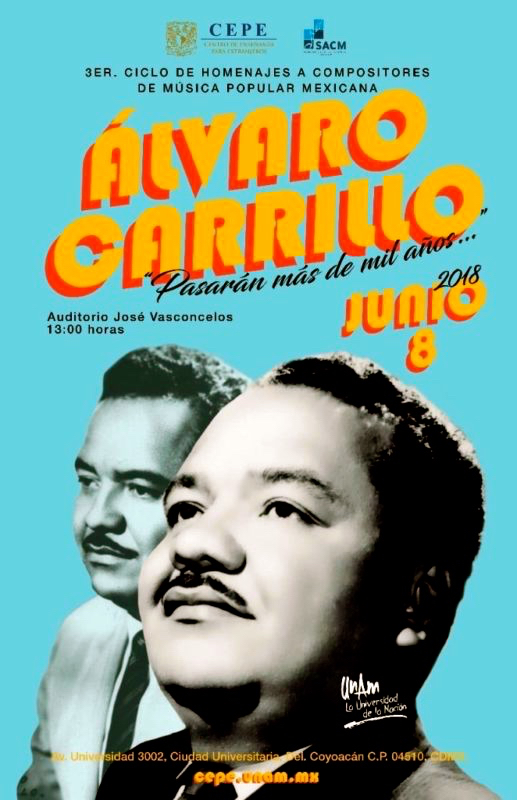

The tune was written in 1959 by Alvaro Carrillo, one of Mexico’s top composers during the golden era of the romantic bolero. Since then, it has been recorded scores of times by an array of stars in multiple languages and a variety of styles.

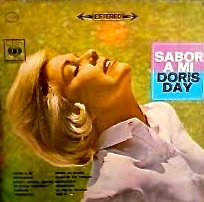

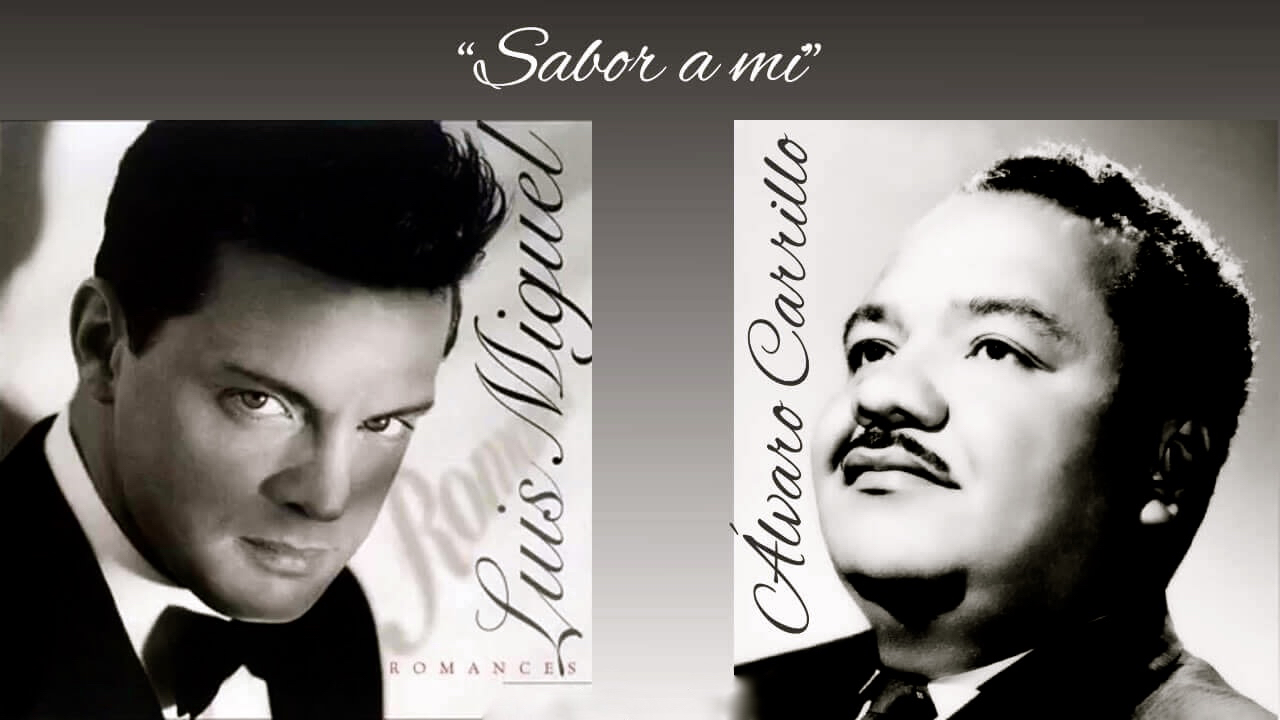

A YouTube search yields amazingly diverse interpretations: an instrumental by Cuba’s father/son piano duo Bebo and Chucho Valdés; a version with alternating vocals, in excellent Spanish, by the South Korean boy band Exo-K; a top-selling pop version by Mexican superstar Luis Miguel; a spare and wispy version by the young, Virginia-born Colombian-American singer Kali Uchis; a jazzy/folksy adaptation by the Bogotá-based band Monsieur Periné; an easy-listening rendition by soft-jazz saxophonist Kenny G; an accordion-accented, Tex-Mex version by American roots band The Mavericks; a low-key, bilingual version by 1950s singer and screen star Doris Day; a classic version by Chilean crooner Lucho Gatica with a Latin big-band sound; and a schmaltzy instrumental version by the Baja Marimba Band, from the 1960s Tijuana-Brass era.

A YouTube search yields amazingly diverse interpretations: an instrumental by Cuba’s father/son piano duo Bebo and Chucho Valdés; a version with alternating vocals, in excellent Spanish, by the South Korean boy band Exo-K; a top-selling pop version by Mexican superstar Luis Miguel; a spare and wispy version by the young, Virginia-born Colombian-American singer Kali Uchis; a jazzy/folksy adaptation by the Bogotá-based band Monsieur Periné; an easy-listening rendition by soft-jazz saxophonist Kenny G; an accordion-accented, Tex-Mex version by American roots band The Mavericks; a low-key, bilingual version by 1950s singer and screen star Doris Day; a classic version by Chilean crooner Lucho Gatica with a Latin big-band sound; and a schmaltzy instrumental version by the Baja Marimba Band, from the 1960s Tijuana-Brass era.

Believe it or not, there’s even a surprisingly tender take on the tune in English (“Close To Me”) by mass murderer Charles Manson, in a vocal style smacking of Willie Nelson.

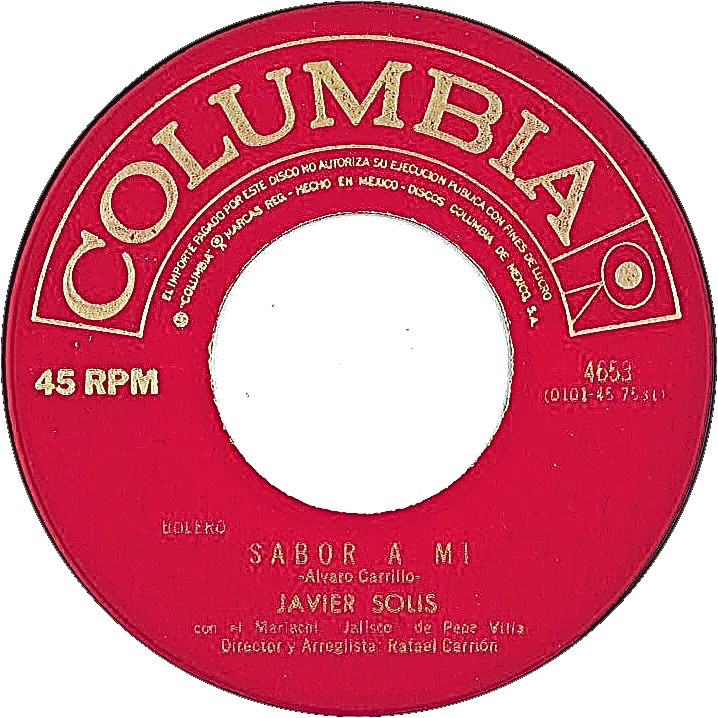

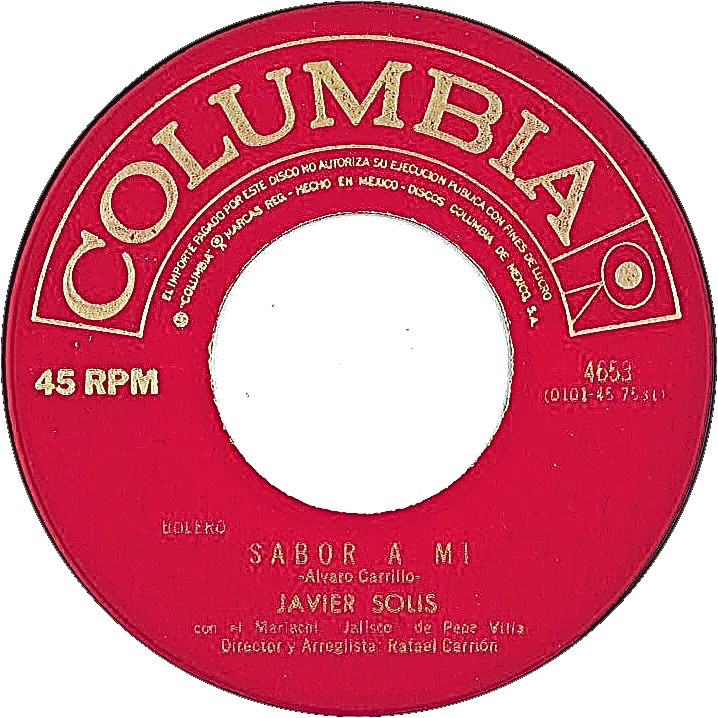

The Frontera Collection contains 25 recordings of the song, including a particularly noteworthy rendition by Mexico’s Javier Solis on Columbia (discussed further below).

“Sabor a Mí” has been recorded in French, Japanese, German, Mandarin, Portuguese, Russian, Italian, and the Zapotec language of Oaxaca, the composer’s home state. In the case of English, however, the lyrics lose their lyricism in a straight translation.

“Sabor a Mí” has been recorded in French, Japanese, German, Mandarin, Portuguese, Russian, Italian, and the Zapotec language of Oaxaca, the composer’s home state. In the case of English, however, the lyrics lose their lyricism in a straight translation.

Literally, the title means “a taste of me.” Yet, the word “sabor” suggests much more than “taste,” as one of the five senses. It connotes flavor, style, zest, gusto, and an intangible essence of something or someone. Music made with “sabor” has swing. Those who dance with “sabor” have flair and feeling. And of course, a chef with “sabor” has a passionate touch for tastiness.

Use of the Spanish article (“a”) in the title also makes a difference. Normally, the word “of” is translated as “de” in Spanish. The song “A Taste of Honey,” for example, could be translated as “sabor de miel,” as in literally savoring the sweet substance. But “sabor a miel” would be less specific, meaning something leaves a hint of honey, or has a flavor that evokes honey.

So “Sabor a Mí” does not mean you take a bite out of your boyfriend. It is not so much “a taste of me” as it is a sensual trace of a loved one’s ethereal memory, like perfume that lingers in the air, or a missing person’s aroma woven into the threads of their clothing. Sabor is the air of someone, an indefinable essence that triggers a physical yearning, a hunger for their lost love.

The composer, however, did not sweat over etymology to come up with the famous title. The word choice occurred to him by chance at a dinner party. In his blog, Con Sabor a Mi Padre, Carrillo’s son, Mario Carrillo Incháustegui, gives the following account of how the song was born, as told by his aunt, Guadalupe Incháustegui Guzmán, his mother’s sister.

In the spring of 1957, Alvaro Carrillo met his future wife, Ana María Incháustegui, through her cousin, who was secretly in love with her. The cousin planned to bring a serenata to Anita for her 24th birthday but without revealing his amorous feelings. So, knowing that she admired Carrillo’s love songs, he invited his friend, the composer, to help with the serenade. What he didn’t plan on was the outcome: It was love at first sight for the songwriter. By the end of that year, Alvaro and Ana María were engaged.

In December, the couple attended a Christmas dinner where Carrillo started drinking shots of whiskey. At one point, his betrothed complained that he was over-indulging, but the songwriter stubbornly continued to drink, and lean in for a kiss. He went on alternating shots and smooches through the night.

Finally, Ana María remarked that she was getting drunk from so many besos borrachos, drunken kisses. Although she wasn’t drinking, she told her fiancée that he was leaving the taste of whiskey (“sabor a whiskey”) in her mouth. The musician paused and said, “What you have in your mouth is not the taste of whiskey, but the taste of me…sabor a mí.”

The way the younger Carrillo tells it, a light went on simultaneously above his parents’ heads.

“Both of them, accomplices in composition, understood at that moment that the phrase arising from the complaint was a poetic expression that should be converted into song,” Mario Carrillo recalled. “My mother wrote it down like a homework assignment for my father. And, breaking her sobriety, she took a drink from his glass, and they toasted to what would become the biggest hit Alvaro Carrillo ever wrote.”

Tanto tiempo disfrutamos de éste amor,

nuestras almas se acercaron, tanto así,

que yo guardo tu sabor

pero tú llevas también... sabor a mí

Si negaras mi presencia en tu vivir

bastaría con abrazarte y conversar

tanta vida yo te di

que por fuerza llevas ya... sabor a mí

No pretendo ser tu dueño

no soy nada, yo no tengo vanidad

de mi vida, doy lo bueno

soy tan pobre, qué otra cosa puedo dar

Pasarán más de mil años, muchos más

yo no sé si tenga amor la eternidad

pero allá tal como aquí

en la boca llevarás... sabor a mí

Carrillo, a member of Mexico’s composers’ society, Sociedad de Autores y Compositores de México, registered the song on July 11, 1958, with publisher Promotora Hispano Americana de Música (PHAM). The publishing contract indicates the song was already set to be recorded by Los Tres Ases for RCA. In his blog, Carrillo notes his father’s composition was first recorded in 1959 but he doesn’t cite the artist.

The following year, young Mexican singer Javier Solis had the first big hit with the tune. Some 40 years later, Solis’ 1960 rendition on Columbia was among the inaugural recordings inducted into the 2001 Latin Grammy Hall of Fame, along with other timeless singles such as "Bésame Mucho" by Pedro Vargas (RCA 1941), "El Día Que Me Quieras" by Carlos Gardel (RCA/Victor 1935), "El Reloj" by Lucho Gatica (Odeón Chilena 1959), "The Girl From Ipanema" by Antonio Carlos Jobim (Verve 1963), "Mambo #5" by Pérez Prado (RCA Victor 1950), and "Oye Como Va" by Santana (Columbia 1970).

The following year, young Mexican singer Javier Solis had the first big hit with the tune. Some 40 years later, Solis’ 1960 rendition on Columbia was among the inaugural recordings inducted into the 2001 Latin Grammy Hall of Fame, along with other timeless singles such as "Bésame Mucho" by Pedro Vargas (RCA 1941), "El Día Que Me Quieras" by Carlos Gardel (RCA/Victor 1935), "El Reloj" by Lucho Gatica (Odeón Chilena 1959), "The Girl From Ipanema" by Antonio Carlos Jobim (Verve 1963), "Mambo #5" by Pérez Prado (RCA Victor 1950), and "Oye Como Va" by Santana (Columbia 1970).

Alvaro and Ana María were married on July 21 of that same year. And they stayed together for almost a decade until a tragic car crash took their lives on April 3, 1969. The composer, who was 47, left a legacy of more than 300 compositions, including other enduring gems such as “La Mentira (Se Te Olvida),” “El Andariego,” “Luz de Luna,” and “Sabrá Dios.”

Today, more than half a century after its debut in Mexico City, “Sabor a Mí” is still popular among young Mexican-Americans, often played at weddings, quinceañeras, anniversaries, or backyard parties. It is one of a handful of Spanish-language tunes that consistently appear among sets of English-language oldies, the Fifties-era rock, doo-wop, lowrider, and R&B tunes so popular among young Chicanos.

In a 2009 reader’s poll conducted by the culture blog LA Eastside, “Sabor a Mí” was nominated as one of the songs that best “embodies the broad richness and historical flavor” of East Los Angeles. Coincidentally, the poll was published the year the composition marked its 50th anniversary. The blog was new at the time, launched the year before by Al Guerrero (aka AlDesmadre), an artist and one-time UCLA student who was born in Ciudad Juarez and raised in East L.A. since age two.

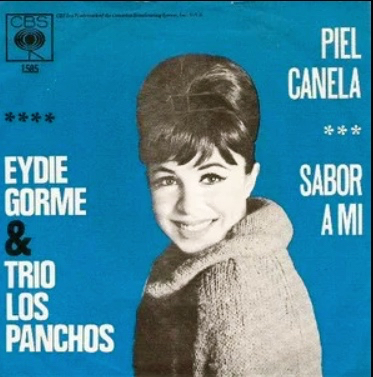

The version picked by Eastside’s readers was recorded in New York in 1964 by Trio Los Panchos and Eydie Gormé. It was included in the album Amor, the first in a series of top-selling Columbia LPs pairing the popular Mexican guitar trio with the Bronx-born pop singer, performing Latin American pop standards.

The enduring appeal of their version among second- and third-generation Mexican Americans may be due to the binational and bicultural quality of the act itself. Los Panchos represented the strong Mexican identity of the generation that came of age in Mexico during the 1940s and ’50s. And Eydie Gormé, the daughter of Sephardic Jews who came from Italy and Turkey and spoke Ladino at home, represented the acculturated immigrant still tentatively tied to ancestral roots. Chicanos may have perceived the faint hint of an Anglo accent in her pronunciation of Spanish lyrics, making them both sympathetic and simpatico. The singer became so closely identified with Latinos that she earned the affectionate nickname, La Gormé.

During the 1970s, “Sabor a Mí” gained new fans as a young generation of L.A. bands recorded fresh versions with modern inflections. This came during a turbulent era of the Chicano Movement, when Mexican Americans were demanding their rights and reclaiming their cultural roots. This one bolero was embraced as part of that cultural resurgence, which also produced Santana’s Latin-rock style and the brown-eyed soul explosion spearheaded in L.A. by bands such as Tierra and Thee Midniters.

Los Lobos, the most critically acclaimed Chicano band of that era, recorded “Sabor a Mí” for their 1978 debut album, Just Another Band From East L.A. Except for a guitar solo with jazzy touches, and some cool background harmonies, they delivered a mostly traditional, trio-style treatment, sung competently by Cesar Rosas. This was the early, folk-oriented phase of Los Lobos, who would go on to experiment with rock, blues, and Latin fusions in the 1980s.

But by far the most emblematic version for Mexican Americans was the one by an East L.A. band whose name represented both the people and the movement – El Chicano. The bolero appeared on the group’s second album, Revolución, released in 1971. Once again, the lead vocalist was a woman, Ersi Arvizu, a former boxer and FedEx driver, also raised in East L.A.

But by far the most emblematic version for Mexican Americans was the one by an East L.A. band whose name represented both the people and the movement – El Chicano. The bolero appeared on the group’s second album, Revolución, released in 1971. Once again, the lead vocalist was a woman, Ersi Arvizu, a former boxer and FedEx driver, also raised in East L.A.

In his book, Barrio Rhythm: Mexican American Music in Los Angeles, UCLA musicologist Steven Loza writes that this recording by El Chicano “is still remembered as one of the most important musical legacies of its period in East Los Angeles.”

Evidence of that enduring legacy appears on the Internet, where the group’s version of the song has tallied almost 6 million views on YouTube, and more than 1,600 comments. The video was posted in 2007 on a Chicano oldies channel that has racked up almost half a billion views in 12 years.

One of the commenters is none other than Arvizu herself.

“When I learned this song by Eydie Gormé and recorded it with El Chicano, never in my wildest dreams did I imagine that this would become my ‘signature song,’ ” the singer wrote, when the video had half its current views. “Here it is over 3 million plays, WOW!! I'm truly humbled by your love and support of this song. I'm no longer with El Chicano, but realize that it took everyone in the group to make this song what it is today. Peace, love and music.”

The question remains: Why did this specific song, above all other boleros, strike a chord with Chicanos?

The question remains: Why did this specific song, above all other boleros, strike a chord with Chicanos?

Dionne Espinoza, professor of Women's, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at Cal State Los Angeles, argues that El Chicano’s rendition with Ersi Arvizu is not simply a romantic song. She calls it “a representation of the politics and aesthetics of the Chicano Movement in East Los Angeles,” as she wrote in an essay that borrows the song’s opening phrase, “ ‘Tanto Tiempo Disfrutamos…’ Revisiting the Gender and Sexual Politics of Chicana/o Youth Culture in East Los Angeles in the 1960s.”

“In the case of ‘Sabor a Mí,’ the reclaiming of the bolero connected its listeners historically to the music that had been the background to their parents’ and grandparents’ daily lives. Yet the song’s rendering by El Chicano as a hybrid music spoke to the community’s cultural complexity,” writes Espinoza in her essay, published in 2003 in the collection Velvet Barrios: Popular Culture and Chicana/o Sexualities, edited by Alicia Gaspar de Alba and Tomas Ybarra-Frausto.

Almost four decades later, as I recount in my story for the Los Angeles Times, Arvizu was coaxed out of retirement by roots-music musician Ry Cooder, best known for his work with Cuba’s Buena Vista Social Club. In 2008, Cooder produced the singer’s first solo album, Friend for Life, mostly featuring songs she wrote. Arvizu was 59 at the time.

Cooder was impressed by both the timeless quality of Arvizu’s style, and the enduring nature of the song that had first made her famous.

"They never forgot that song, that 'Sabor a Mí,’ ” he said in a 2008 interview with the San Francisco Chronicle. “It was a million-seller, ferchrissake. In East L.A., they don't forget. The tune is still there for them.”

– Agustín Gurza

Blog Category

Tags

Images