The Tango: Thriving Through Constant Renewal

The Argentine tango is one of a handful of song-and-dance styles – along with Spanish flamenco and the Cuban mambo – that emerged from cultural fusions in the Spanish-speaking world and gained global popularity in the 20th century. The tango craze that swept Europe and the U.S. during the first half of the last century may have faded. But the tango as an art form still thrives, in both traditional and contemporary forms.

The Argentine tango is one of a handful of song-and-dance styles – along with Spanish flamenco and the Cuban mambo – that emerged from cultural fusions in the Spanish-speaking world and gained global popularity in the 20th century. The tango craze that swept Europe and the U.S. during the first half of the last century may have faded. But the tango as an art form still thrives, in both traditional and contemporary forms.

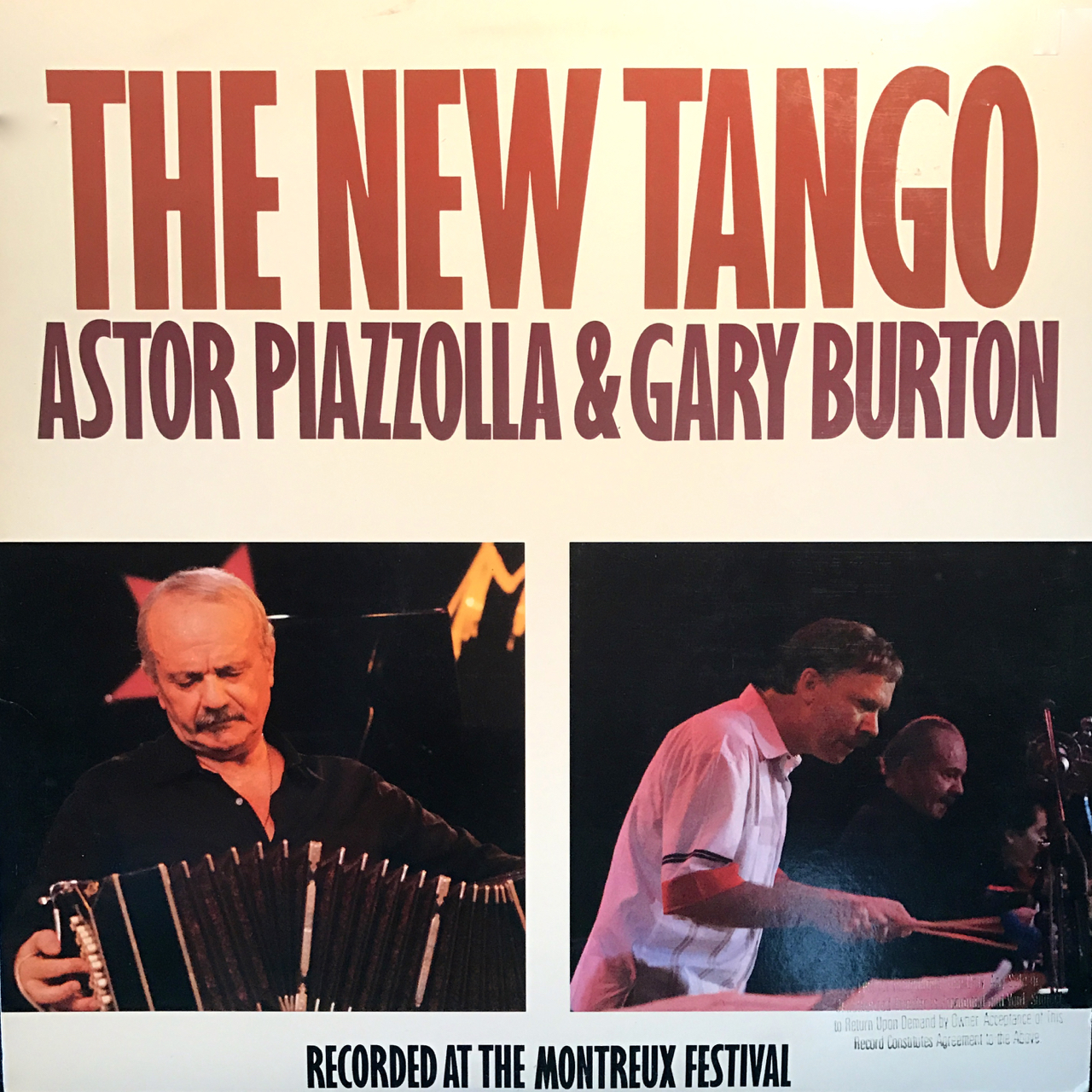

With a history that dates to the late 1800s, the tango has proven remarkably adaptable. The genre’s flexibility has allowed it to blend smoothly with jazz, flamenco, bolero, and salsa, not to mention American pop adaptations that, turned the tango into a rose-between-the-teeth stereotype. In the United States, the genre’s commercial success was propelled by both film and records, including many historic 78-rpm recordings made in New York by the top tango musicians of the day.

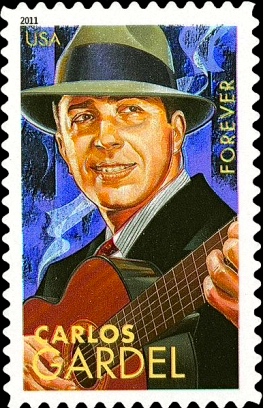

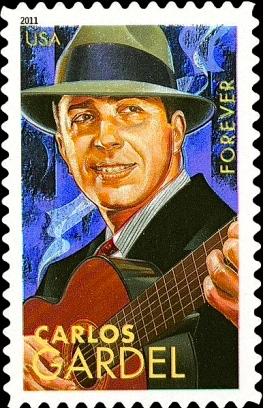

I was reminded of the tango’s transcendent qualities recently by a Facebook post written by my younger brother, Roberto Gurza, a clinical psychologist working in Colorado. In it, he happened to mention the classic tango “Nostalgias,” which evoked memories of our father’s penchant for playing records on his 1950s stereo console. My brother compared two versions of the song: an old-school rendition by Carlos Gardel, Argentina’s tango singer par excellence, and a modern, flamenco-tinged version by Spanish singer Buika, with her smoldering, smoky jazz vocals. As a kid, he considered the former corny; the new version now made it meaningful for him.

I was reminded of the tango’s transcendent qualities recently by a Facebook post written by my younger brother, Roberto Gurza, a clinical psychologist working in Colorado. In it, he happened to mention the classic tango “Nostalgias,” which evoked memories of our father’s penchant for playing records on his 1950s stereo console. My brother compared two versions of the song: an old-school rendition by Carlos Gardel, Argentina’s tango singer par excellence, and a modern, flamenco-tinged version by Spanish singer Buika, with her smoldering, smoky jazz vocals. As a kid, he considered the former corny; the new version now made it meaningful for him.

My brother’s post reminded me of the first time I discovered the song, in a roundabout way through salsa music. I can’t pretend to be a tango expert, but I was always fascinated by the tango tunes that were occasionally included on albums from the salsa boom of the 1970s, when I was in college.

The version of “Nostalgias” I first heard was done bolero-style by eccentric salsa singer Angel Canales, whose vocals have some of the weird, word-mashing, nasal phrasing associated with Bob Dylan! It’s an offbeat take on the song, admittedly, but I was taken by the sheer, wrist-slashing heartbreak of the lyrics, an agony accentuated by Canales’s quirky, emotional flair. His version ends with his improvisations as the band kicks into a steady, slow-dance beat.

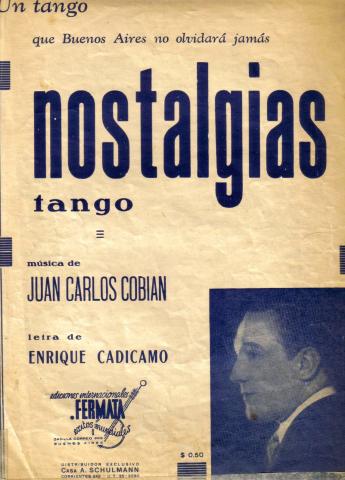

The Canales album does not credit the song’s famous composers: pianist Juan Carlos Cobían and his longtime collaborator, lyricist Enrique Cadícamo. Their tune was featured in the 1937 film, Así Es el Tango, a musical comedy made in Argentina. In this clip at the 40-minute mark, a heartbroken character plays the soon-to-be-famous melody on the piano for a friend. A year earlier, “Nostalgias” had been recorded by Charlo, a top tango artist, accompanied only by guitars, as were many early tangos. (Charlo also waxed a stunning version of the song with orchestra that can be heard on the specialty website TodoTango.com.) Three decades later, Libertad Lamarque, considered the first lady of tango, performed the song in the film El Hijo Pródigo, made in Mexico where Lamarque was a beloved figure.

The Canales album does not credit the song’s famous composers: pianist Juan Carlos Cobían and his longtime collaborator, lyricist Enrique Cadícamo. Their tune was featured in the 1937 film, Así Es el Tango, a musical comedy made in Argentina. In this clip at the 40-minute mark, a heartbroken character plays the soon-to-be-famous melody on the piano for a friend. A year earlier, “Nostalgias” had been recorded by Charlo, a top tango artist, accompanied only by guitars, as were many early tangos. (Charlo also waxed a stunning version of the song with orchestra that can be heard on the specialty website TodoTango.com.) Three decades later, Libertad Lamarque, considered the first lady of tango, performed the song in the film El Hijo Pródigo, made in Mexico where Lamarque was a beloved figure.

For comparison, consider this 1957 recording by American bandleader Freddy Martin, with “Nostalgias” translated as “My Lost Love.” In the video, a Lawrence Welk-style announcer introduces the number with a line suited for a mid-century ballroom: “Well, a dancing party wouldn’t be quite complete without the graceful beat of a tango.”

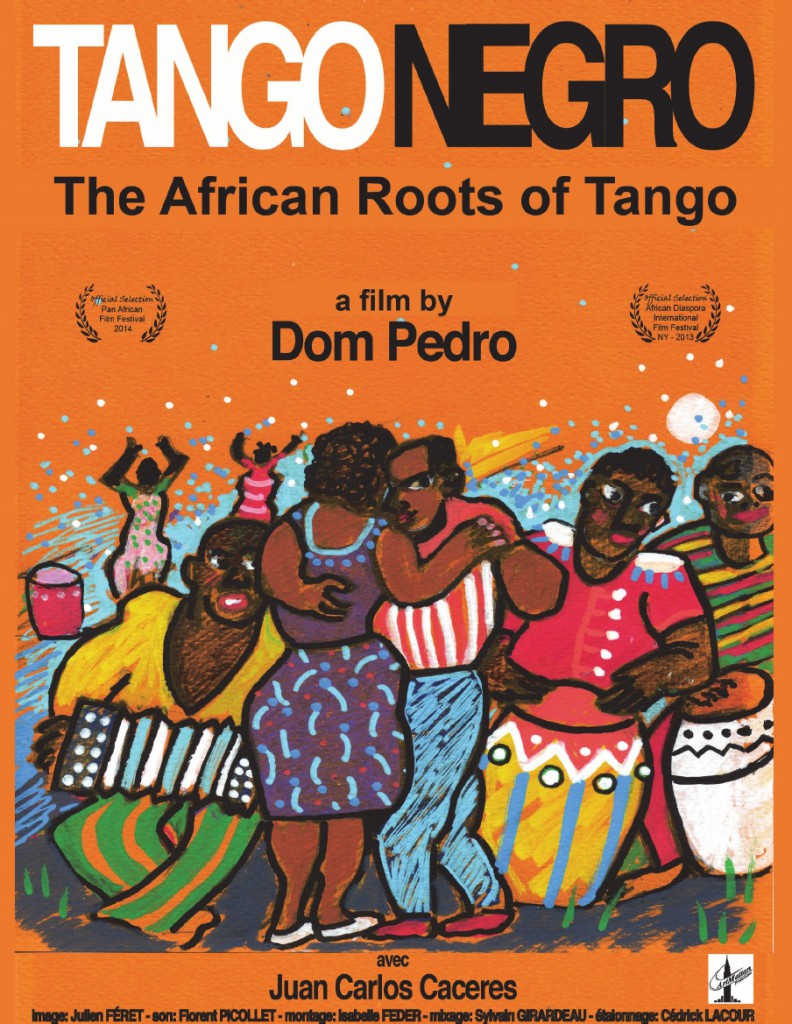

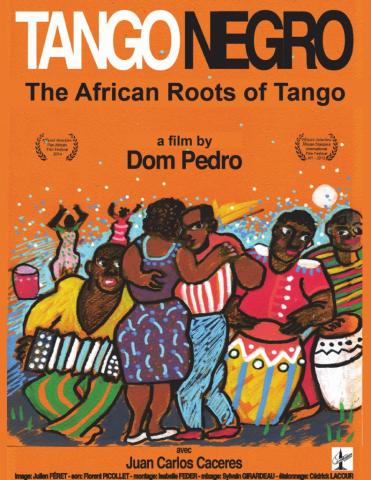

You can hear a vast difference in these interpretations. The American version is a little too march-like and metronomic. The authentic tango is much more modulated – fast and slow, loud and soft, high and low – like the Argentine speaking accent itself. The genre, however, is not exclusive to Argentina. Its roots extend through the region around the Rio de la Plata, which marks the border between Argentina and Uruguay. Montevideo is also a tango capital, and in fact, the style shares similar origins with the Uruguayan candombé, a folk genre with African roots.

Tango also shares its African and Spanish ancestry with those other aforementioned song-and-dance styles, flamenco and Afro-Cuban. Not surprisingly, all three were originally disdained as vulgar and immoral music of the unwashed lower classes. As with American blues, the scorned styles turned out to be revolutionary, and eventually emerged as a global, pop-culture force. (There are plenty of tango histories available, both in English and Spanish.)

Tango also shares its African and Spanish ancestry with those other aforementioned song-and-dance styles, flamenco and Afro-Cuban. Not surprisingly, all three were originally disdained as vulgar and immoral music of the unwashed lower classes. As with American blues, the scorned styles turned out to be revolutionary, and eventually emerged as a global, pop-culture force. (There are plenty of tango histories available, both in English and Spanish.)

In the United States, the tango became a commercial commodity, watered down for mass consumption. Audiences here are perhaps most familiar with the campy tango tune “Hernando’s Hideaway,” from the 1957 film, Pajama Game. The song, in its most popular rendition by Archie Bleyer, features Spanish castanets and the exclamation “Olé!”—neither of which have anything to do with tango, proving once again that cultural authenticity is not a Hollywood priority. There are versions of the song by The Everly Brothers (regrettably), Ella Fitzgerald (interestingly), and Harry Connick Jr (lamely) in a Broadway revival of the play.

In the U.S., fascination with the tango continued through the new millennium, with Broadway productions such as Tango Argentino (1985) and Forever Tango (1994), as well as Spanish director Carlos Saura’s sumptuous film Tango (1998). Then in 2002, a whole new incarnation, dubbed “el nuevo tango tecno,” was created by the band Bajofondo, led by Gustavo Santaolalla, the famed Argentine musician based in L.A.

A search of the Frontera Collection yields almost 1,000 tango recordings, and those are just the ones that are identified by genre on the record label or in the song title. The archive does not specify a genre if it’s not on the label. Thus, there are likely many more tangos in the collection than those that appear in a genre search.

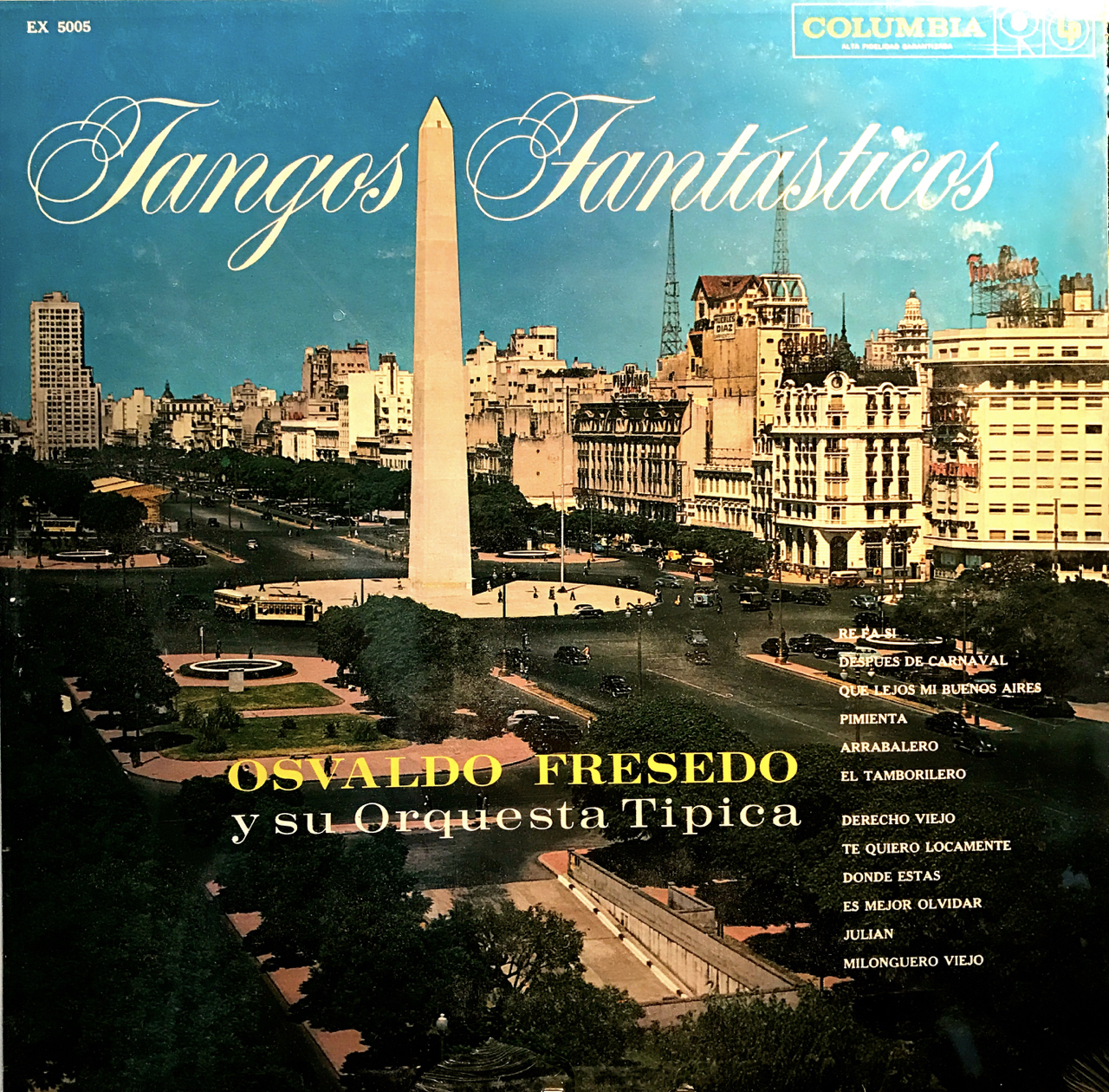

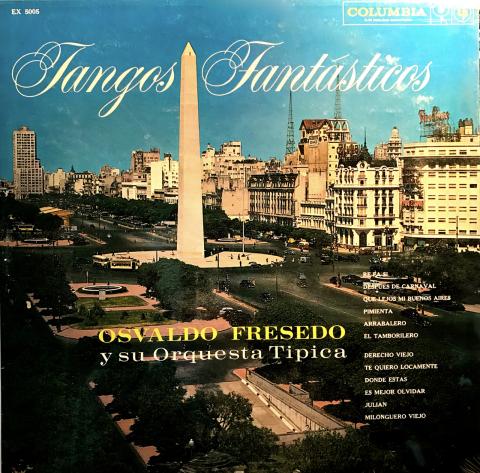

Searching by artist reveals dozens of recordings by major tango stars, including Juan D’Arienzo, Anibal Troilo, Francisco Canaro, Osvaldo Fresedo, Hugo del Carril, Libertad Lamarque, and Carlos Gardel.

Searching by artist reveals dozens of recordings by major tango stars, including Juan D’Arienzo, Anibal Troilo, Francisco Canaro, Osvaldo Fresedo, Hugo del Carril, Libertad Lamarque, and Carlos Gardel.

A search by song title yields many recordings of tangos that have become Latin standards – “Adios Muchachos,” “Cuesta Abajo,” “El Choclo,” “La Cumparsita” – interpreted by artists ranging from the great Gardel with bandoneón, the classic tango instrument similar to an accordion, to Flaco Jimenez with his Tex-Mex squeezebox. Gardel’s tango “Por Una Cabeza” was used in the dance scene from Scent of a Woman, starring Al Pacino.

The Frontera Collection also contains an entire album of tangos by Agustín Lara, the Cole Porter of Mexico, entitled “Tangos De Agustin Lara 1929-1939: Grabaciones Originales.” And, as another example of genre-crossing, there’s a whole album of Mexican rancheras done tango-style, complete with orchestra and Argentine inflections, entitled “Las Mas Bonitas Canciones Mexicanas Al Estilo Pampero,” by Alfredo Antonio.

I was surprised to find in the archive a song by one of my favorite Puerto Rican groups from the ’70s and ’80s: Haciendo Punto en Otro Son, part of a musical wave that revived the island’s folkloric roots. The song, simply called “Tango,” is a parody that uses slapstick lyrics about underwear to mock the genre’s melodrama. It was not a coincidence that the Caribbean group’s lead singer, Tony Croatto, was an Argentine transplant to the island.

I was surprised to find in the archive a song by one of my favorite Puerto Rican groups from the ’70s and ’80s: Haciendo Punto en Otro Son, part of a musical wave that revived the island’s folkloric roots. The song, simply called “Tango,” is a parody that uses slapstick lyrics about underwear to mock the genre’s melodrama. It was not a coincidence that the Caribbean group’s lead singer, Tony Croatto, was an Argentine transplant to the island.

In a few cases, songs in the archive are identified as tango fusions even if the tango is hard to hear. The conga tango by Mexico’s Toña La Negra is all conga, and the tango flamenco by La Niña de Los Peines is straight-up flamenco. (The gypsy genre actually includes a palo, or sub-category, called tango, though it’s not even close the South American variety.) There’s also this strange mutation called “Inca Tango” by Los Castilians, with its snake-charming flute and passages that smack of paso doble.

My brother will find a few more renditions of “Nostalgias” in this collection. There’s a traditional instrumental version with orquesta tipica, one with mariachi on the Texas-based Falcon label, and a lovely performance by San Antonio singer Eva Garza, with the orchestra conducted by famed composer/arranger Manuel S. Acuña. Garza’s version – with her subtle blend of Mexican and Argentine sensibilities – is identified as a canción tango on the 78’s blue Decca label.

My brother will find a few more renditions of “Nostalgias” in this collection. There’s a traditional instrumental version with orquesta tipica, one with mariachi on the Texas-based Falcon label, and a lovely performance by San Antonio singer Eva Garza, with the orchestra conducted by famed composer/arranger Manuel S. Acuña. Garza’s version – with her subtle blend of Mexican and Argentine sensibilities – is identified as a canción tango on the 78’s blue Decca label.

But the database also contains several unrelated songs with the same title. In fact, there is an entirely different tango named “Nostalgia,” an instrumental performed by Lacalle’s Tango Orchestra on a Columbia 78. Adding to the confusion, Cobían’s original composition is alternately listed also in the singular, “Nostalgia.”

The redundant titles are not so surprising since nostalgia – a yearning for the good old days and memories of the old barrio (el arrabal) – are essential themes in tango music. Songs also touch on positive values that rise above low social status: honesty, family, friendship, respect for mothers, and sidestepping the temptations of gambling, drinking, and sex. On the downside, the tango also wallows in the suffering of amorous betrayal, lost love, despondency, solitude, and even death.

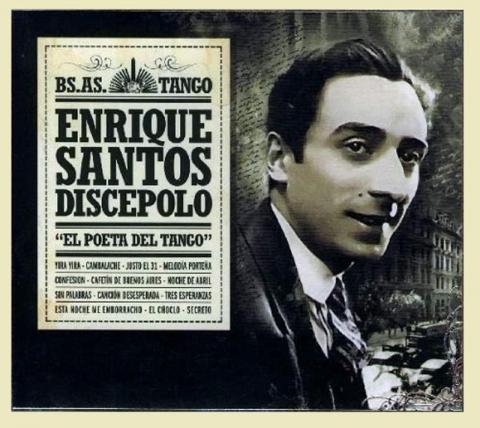

For those who think of tango as just a sensuous and vivacious dance, such morbid and depressing themes may seem misplaced. Yet, they are at the heart of tango culture. In the words of prolific composer Enrique Santos Discépolo, “A tango is a sad thought that dances.” Case in point: His most famous tango, “Cambalache,” a bleak, nihilistic assessment of the human condition in the 20th century.

For those who think of tango as just a sensuous and vivacious dance, such morbid and depressing themes may seem misplaced. Yet, they are at the heart of tango culture. In the words of prolific composer Enrique Santos Discépolo, “A tango is a sad thought that dances.” Case in point: His most famous tango, “Cambalache,” a bleak, nihilistic assessment of the human condition in the 20th century.

Those themes resonated with salsa artists arising from the downtrodden barrios of New York in the turbulent 1970s. Salsa singer Ismael Miranda, a member of the Fania All Stars, introduced me to two classic tangos performed with his salsa orchestra. One is the tearjerker “La Cama Vacía,” or the empty bed. It’s about an ailing man who pens a letter to a friend from his deathbed, begging for a visit because nobody has come to see him. Filled with compassion, the friend rushes to the hospital at the first opportunity, but it’s too late. He finds only the empty bed of the title. Miranda’s melodramatic version features an assertive horn section, and a Santana–like rock guitar as it fades out. By contrast, the Frontera Collection contains a 78-rpm version by the song’s composer, Gregorio Ayala, backed only by a trio of guitars.

The other tango, equally depressing and pessimistic, is entitled “Las Cuarenta,” performed by Miranda as a bolero with a stunning arrangement by Marty Sheller. Written by Roberto Grela with gripping lyrics by Francisco Gorrindo, the song was first recorded in 1937. It paints a grim portrait of a defeated man who returns to his barrio where he ‘took his first steps” and is now embittered by the harsh lessons of life.

Aprendí todo lo malo, aprendí todo lo bueno.

Sé del beso que se compra, sé del beso que se da;

Del amigo que es amigo siempre y cuando le convenga,

Y sé que con mucha plata uno vale mucho más.

Three decades and 5,000 miles separate this tango’s origin in Buenos Aires from its salsa revival in the Bronx. But what ties them together is the same barrio way of life, notes César Miguel Rondón in his socio-cultural analysis, El Libro de La Salsa. The despair and disappointment of poverty, writes the Venezuelan author and critic, “were transported exactly, without any problem, from one extreme of the continent and of Latin American life to the other … . That is why salsa could absorb the tango.”

I had always wondered why young salsa stars chose to interpret tangos. It took 40 years, and a Facebook post, for me to finally understand the common context and connection.

--Agustín Gurza

Blog Category

Tags

Images