La Adelita, Part 1: Feminist Fighter or Chauvinist Creation?

Many countries have iconic images and unofficial anthems that capture the essence of the national spirit. In the United States, there’s the high-stepping tune “Yankee Doodle Dandy.” Sometimes, just a few words are enough to evoke a familiar cause and its historic significance. Rosie the Riveter. The suffragettes. The colonial minutemen. We can easily picture them in our mind’s eye, with any attendant nostalgia or national pride.

Many countries have iconic images and unofficial anthems that capture the essence of the national spirit. In the United States, there’s the high-stepping tune “Yankee Doodle Dandy.” Sometimes, just a few words are enough to evoke a familiar cause and its historic significance. Rosie the Riveter. The suffragettes. The colonial minutemen. We can easily picture them in our mind’s eye, with any attendant nostalgia or national pride.

In Mexico, one iconic female figure embodies that cultural and historic significance. La Adelita, a mythical composite persona, represents the thousands of unknown women who joined the Revolution of 1910, playing various key roles in the popular uprising that overthrew the Eurocentric dictatorship of Porfirio Diaz.

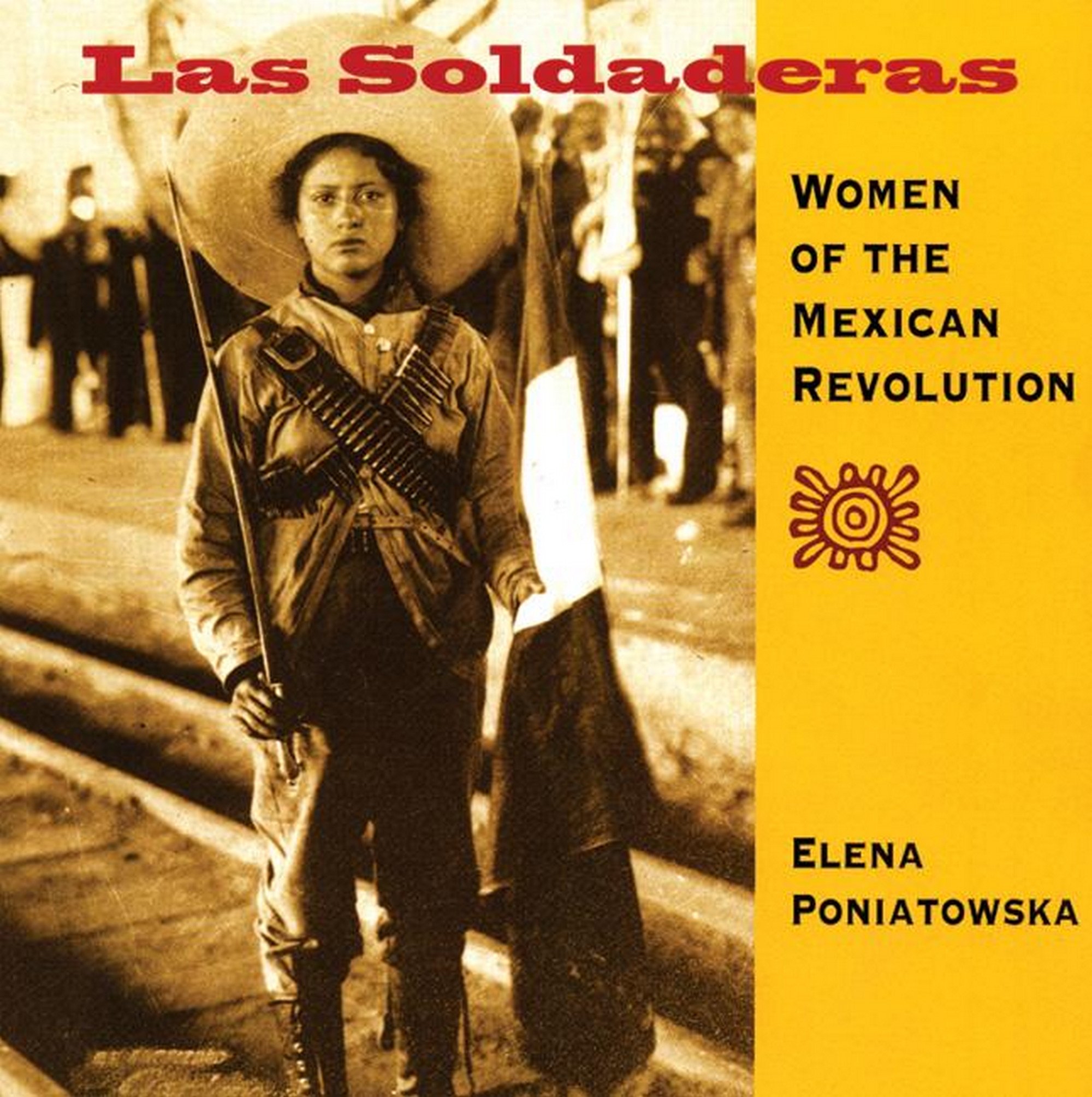

Historically, the women who fought during the Mexican Revolution were called soldaderas, a generic term for female soldiers. But their status as cultural icons came through a song that helped popularize their nickname. “La Adelita” is a corrido that strikes a chord with Mexicans of all political persuasions and social classes. It is as universally embraced as is a song such as “This Land Is Your Land” in the United States.

Yet, mystery still shrouds the origin of the song, and the person it purports to idolize. Controversy also surrounds the meaning of the song’s simple lyrics. On the surface, it is taken to be an ode to the brave but downtrodden women who fought for freedom and equality, an anthem for feminism itself. But a closer read reveals blatantly macho overtones, with a patriarchal perspective that treats women as the object of male desires and even as victims threatened with stalking, disguised as romantic pursuit.

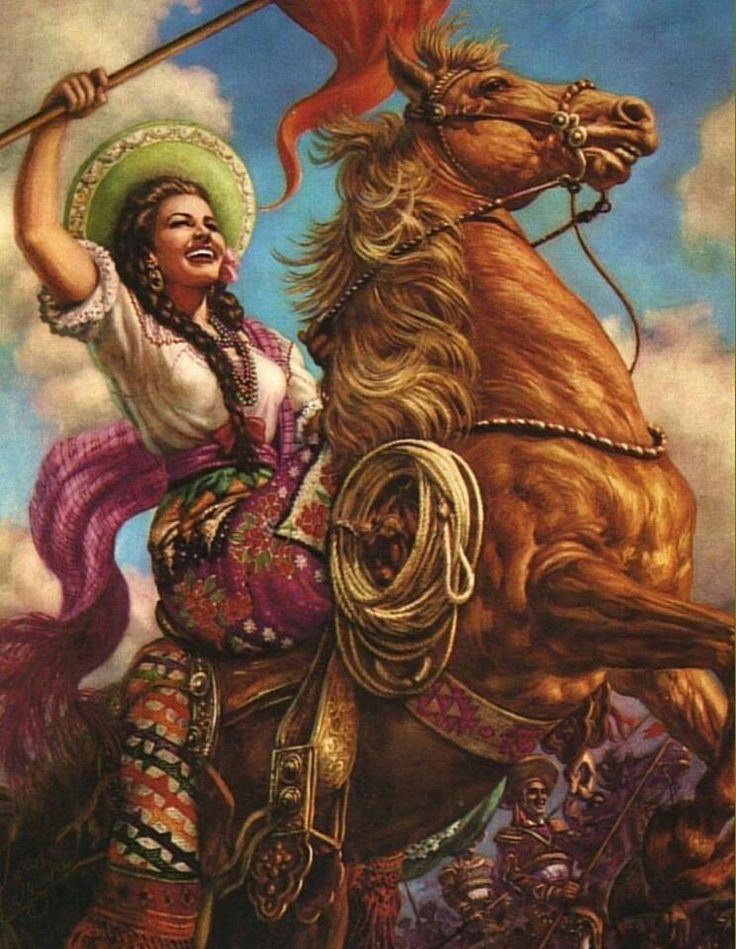

Today, thanks in part to analyses by feminist scholars, a new understanding has emerged of the corrido and its mythical meaning. Far from standing for women’s rights, these scholars say, La Adelita has become a romanticized, even sexualized, figure in popular culture, a figment of male imagination, not of true female liberation.

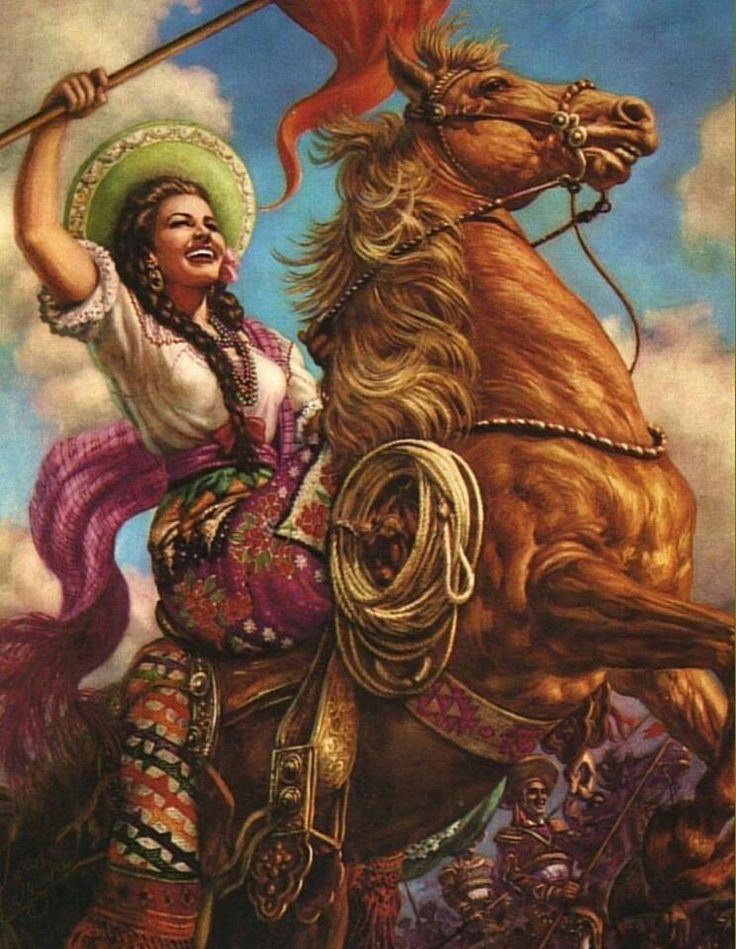

In popular culture – in calendars, comic books, music, and the movies – Las Adelitas are depicted as exotic warriors, wearing low-cut tops and bandoleers across their chests, with Mexican-made Mouser rifles on their backs, and a fiery look in their eyes of both seduction and menace.

“The figure of ‘La Adelita’ … underscores the beauty of woman, her youth, and her bravery in following the men to war. But at the same time, it clouds and complicates the recognition of the many real women who participated in the struggle,” states Gabriela Cano, researcher in gender studies at El Colegio de México, as quoted in El Informador in its coverage of the Centennial of the Mexican Revolution (1910-2010).

“The figure of ‘La Adelita’ … underscores the beauty of woman, her youth, and her bravery in following the men to war. But at the same time, it clouds and complicates the recognition of the many real women who participated in the struggle,” states Gabriela Cano, researcher in gender studies at El Colegio de México, as quoted in El Informador in its coverage of the Centennial of the Mexican Revolution (1910-2010).

Warriors Anonymous

So who were these revolutionary Adelitas who drove soldiers crazy with desire, and how did they get their lyrical name?

No one really knows, and that points to another major issue. Unlike the male leaders of the revolution who are internationally famous, especially Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata, La Adelita is entirely anonymous. She is simply a symbol for the entire group of female fighters, a stand-in for the legion of unnamed women warriors who were key to winning the rebellion.

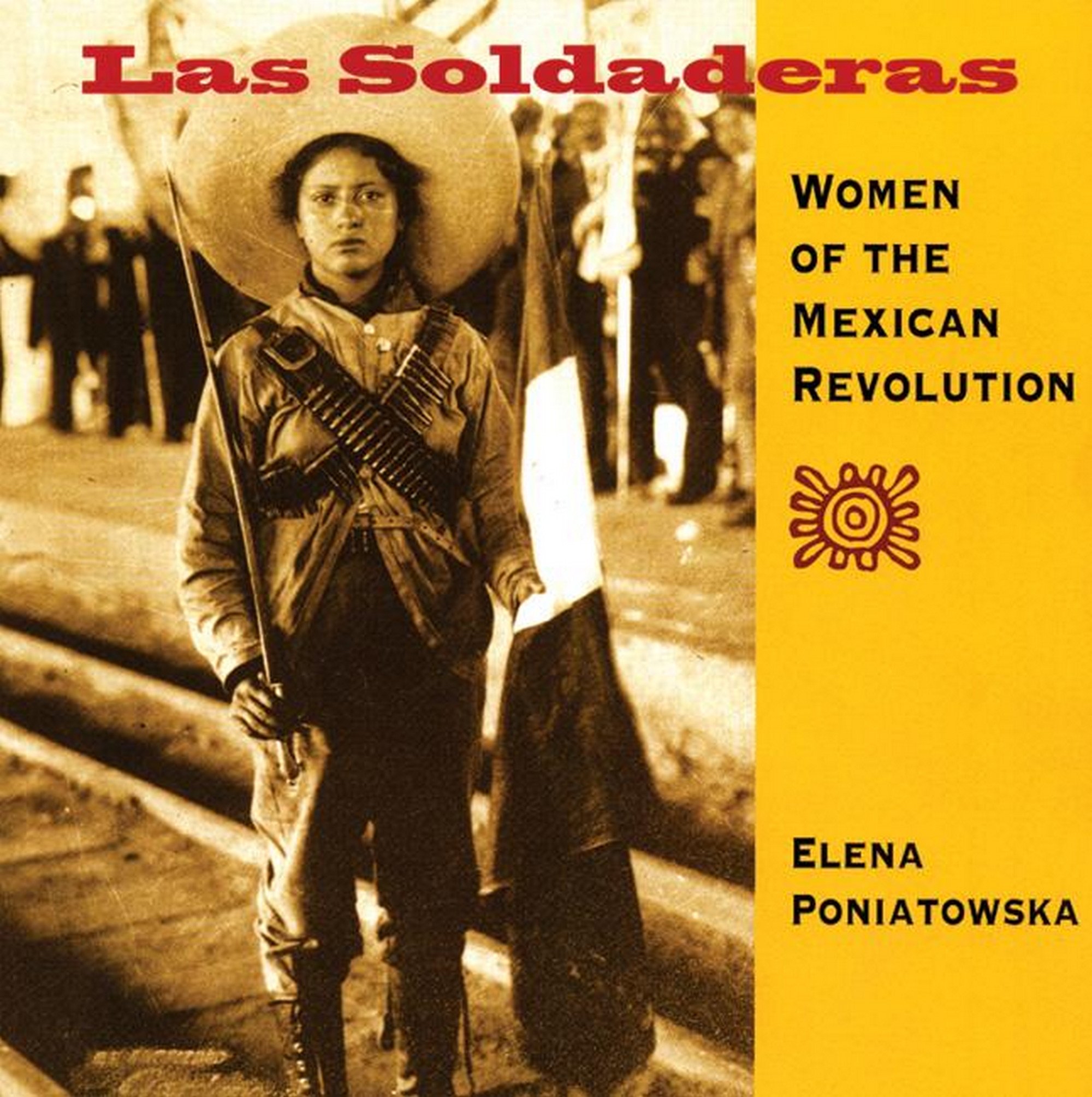

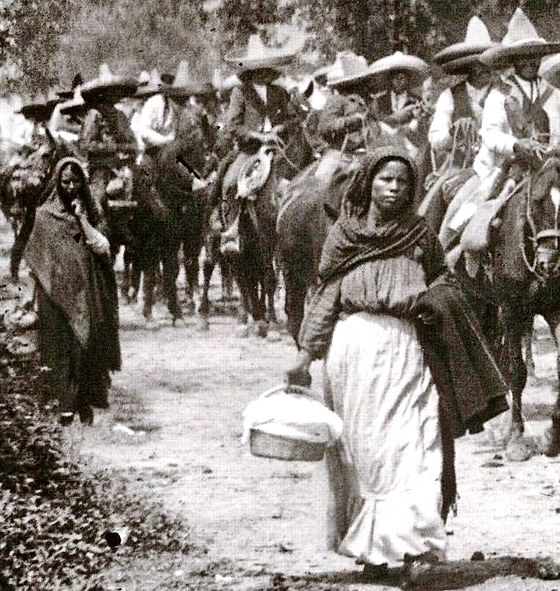

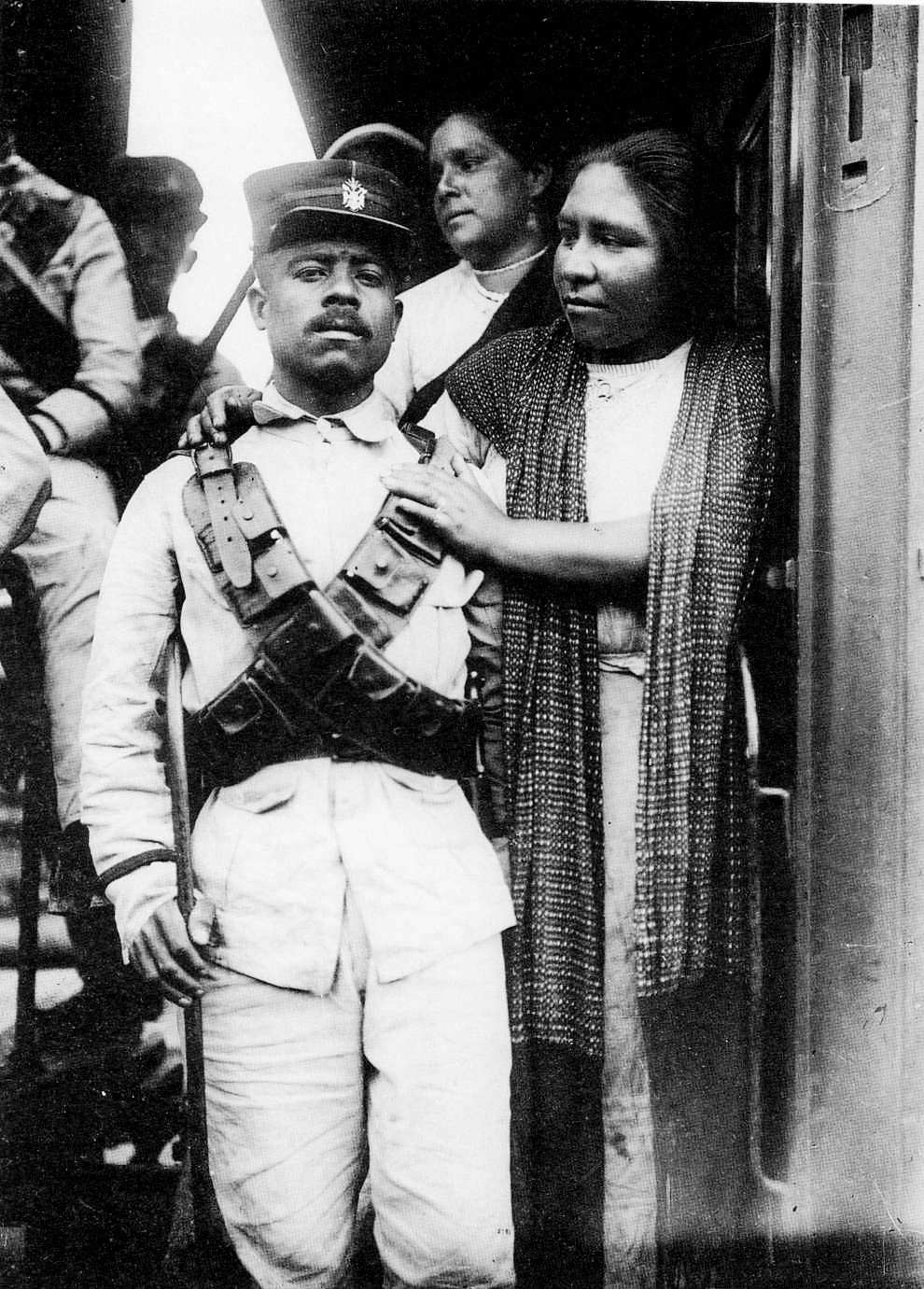

Historically, the memory of Las Adelitas has been kept alive thanks to the corrido, as well as the intrepid photojournalism of Agustín V. Casasola and other pioneering photographers. Often, their vivid images provide the only historical record of these mobilized women. Their grim, dark-skinned faces are captured by the camera lens like ghosts who then vanished.

Historically, the memory of Las Adelitas has been kept alive thanks to the corrido, as well as the intrepid photojournalism of Agustín V. Casasola and other pioneering photographers. Often, their vivid images provide the only historical record of these mobilized women. Their grim, dark-skinned faces are captured by the camera lens like ghosts who then vanished.

No names, no captions, no gravestone to honor their service. Not even a Tomb of the Unknown Adelita.

“In the case of the Adelitas – where the majority were of humble origin, hacienda workers or campesinas – we do not know names and surnames, beyond the very few that appear in specialized history archives,” writes Ximena Rojo In the Mazatlán Post. “History textbook(s) do not talk much about them, beyond the anecdote of Adelita and the corrido. If it were not for the photos of the soldaderas of the Casasola Archive, or for the song of the Adelita, we would not know anything about the women in the Revolution.”

Some argue that minimizing the historical significance of the Adelitas was driven by Mexico’s entrenched social hierarchy determined by class, caste, and color. On the political front, women who took up the liberal fight against the dictatorship were mostly urban, educated, and middle-class. And many of them were known by name, like Hermila Galindo, a feminist who in 1915 founded the weekly magazine La Mujer Moderna that championed women’s right to vote.

On the battlefield, however, the soldaderas were mostly poor, rural, indigenous, and, in society’s eyes, forgettable. Not even the identity of the woman who inspired the famous corrido is known with historical certainty.

Who Is the Real Adelita?

According to popular yet unproven accounts, the song is based on the life of Adela Velarde Pérez, a teenage nurse from Ciudad Juarez. Born in 1900 to a wealthy family, Velarde joined revolutionary forces when she was just 13, much to her parents’ discontent. She hopped on a hospital train of the Mexican Red Cross, and eventually joined the forces of Pancho Villa.

According to popular yet unproven accounts, the song is based on the life of Adela Velarde Pérez, a teenage nurse from Ciudad Juarez. Born in 1900 to a wealthy family, Velarde joined revolutionary forces when she was just 13, much to her parents’ discontent. She hopped on a hospital train of the Mexican Red Cross, and eventually joined the forces of Pancho Villa.

There is no doubt that the young nurse existed. The issue is whether she was the woman who actually inspired the song’s composer, whose identity is also nebulous. An online video tour at the Museo de la Revolucion en la Frontera in Velarde’s hometown also claims she is La Adelita, but offers no more convincing information than that which is in common circulation.

The corrido’s creation story, at this point, begins to read more like a melodramatic movie script than an authentic piece of history. You can hear the film rolls unspool as this fantastic tale unfolds. The following account is from Jose Alberto Galindo Galindo, who wrote a 2009 biography of Velarde – Un Cielo de Metrallas: La Verdadera Historia de La Adelita (A Sky of Shrapnel: The True Story of La Adelita). Galindo, the town historian (cronista) of Zaragoza, Coahuila, near the Texas border, has given talks internationally on her life.

Soon after joining the revolution, Galindo states, Velarde fell in love with a young sergeant in Villa’s army named Antonio Gil del Rio Armenta. The romance was brief, a victim of the ubiquitous violence of the time.

It is 1914, the story goes, and the sergeant is struck by a hail of gunfire while crossing a street during a bloody battle in the town of Gómez Palacio, Coahuila, adjacent to Torreón. Adelita rushes to his side but cannot save him. Mortally wounded, Sgt. Del Rio asks her to retrieve a paper from his rucksack. On it are the lyrics of the song that would become famous. The bleeding soldier penned the words for her, but the song was unfinished. With his dying breath, he recites the final stanza to his lover, who dutifully writes them down before her soldier-poet expires.

Galindo’s stirring account appeared on April 23, 2018, in Del Rio Grande, a magazine published by the now-defunct Del Rio News-Herald. (The community newspaper was founded almost 100 years ago in the small border town of Del Rio, Texas, about 160 miles west of San Antonio, but was forced to close in November due to the pandemic.)

However, reports on the corrido’s composer are contradictory. Some sources claim the lyrics were actually written by Guadalupe Barajas Romero of Patazcuaro, Michoacan. However, his heirs deny that the song was inspired by the aforementioned nurse.

Neither of the alleged composers appear in a search of the Frontera Collection database, which contains 82 recordings of the song in a variety of styles. Nor do the purported composers appear in the comprehensive discography Ethnic Music on Records by Richard K. Spottswood, covering thousands of Spanish-language recordings made in the U.S. from 1893-1942. Neither can they be found in the online annals of the Sociedad de Autores y Compositores de México (SACM), the Mexican composer’s society.

As for the real Adela Velarde, the love-struck nurse, it’s known that she moved to Mexico City after 18 months on the battlefield and took a job in the post office. In 1965, she married Col. Alfredo Villegas, an officer who had served with Francisco Madero, the first revolutionary president. The couple settled in Del Rio, Texas, where Adela Velarde died of ovarian cancer in 1971, four days before her 71st birthday.

As for the real Adela Velarde, the love-struck nurse, it’s known that she moved to Mexico City after 18 months on the battlefield and took a job in the post office. In 1965, she married Col. Alfredo Villegas, an officer who had served with Francisco Madero, the first revolutionary president. The couple settled in Del Rio, Texas, where Adela Velarde died of ovarian cancer in 1971, four days before her 71st birthday.

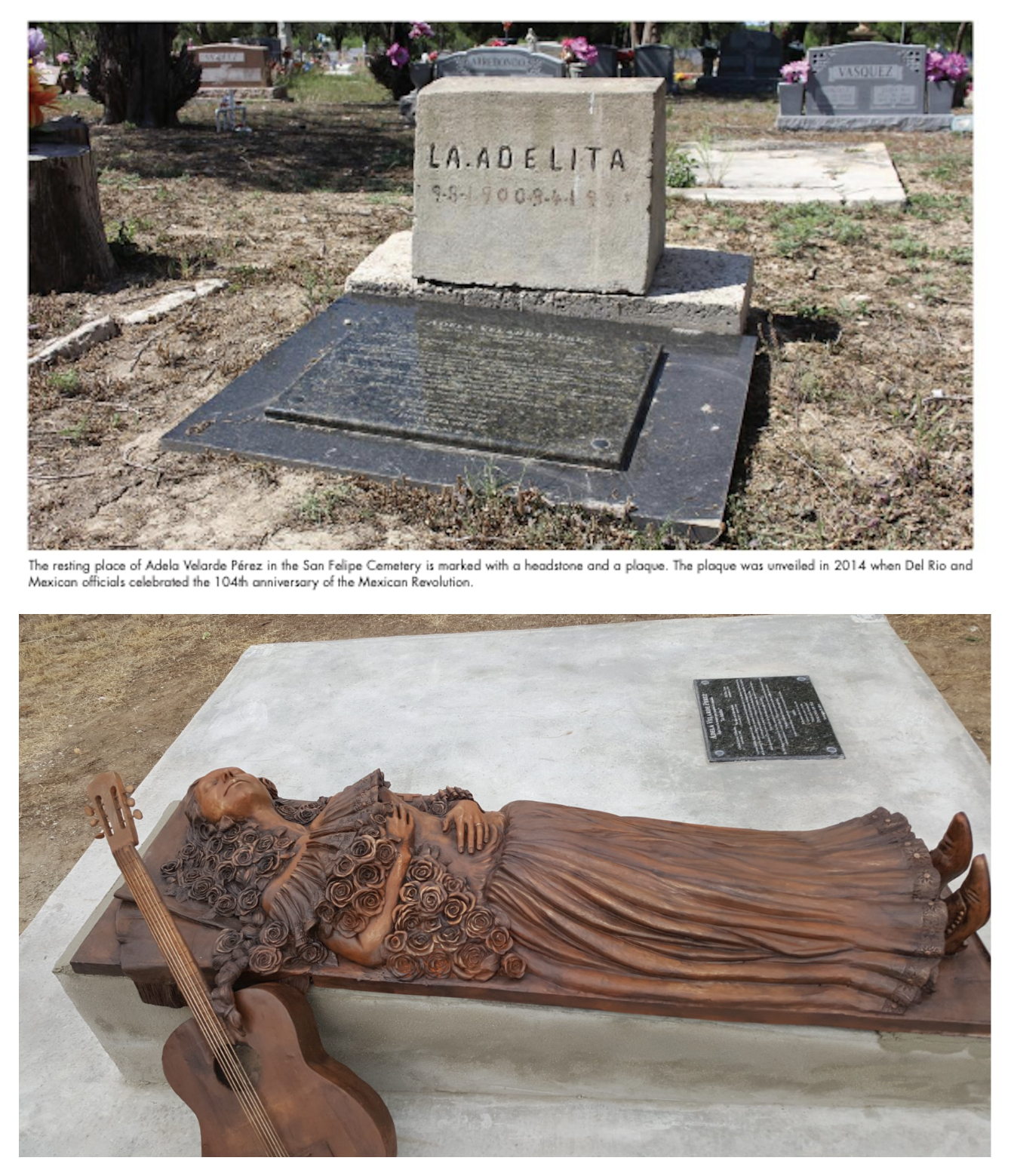

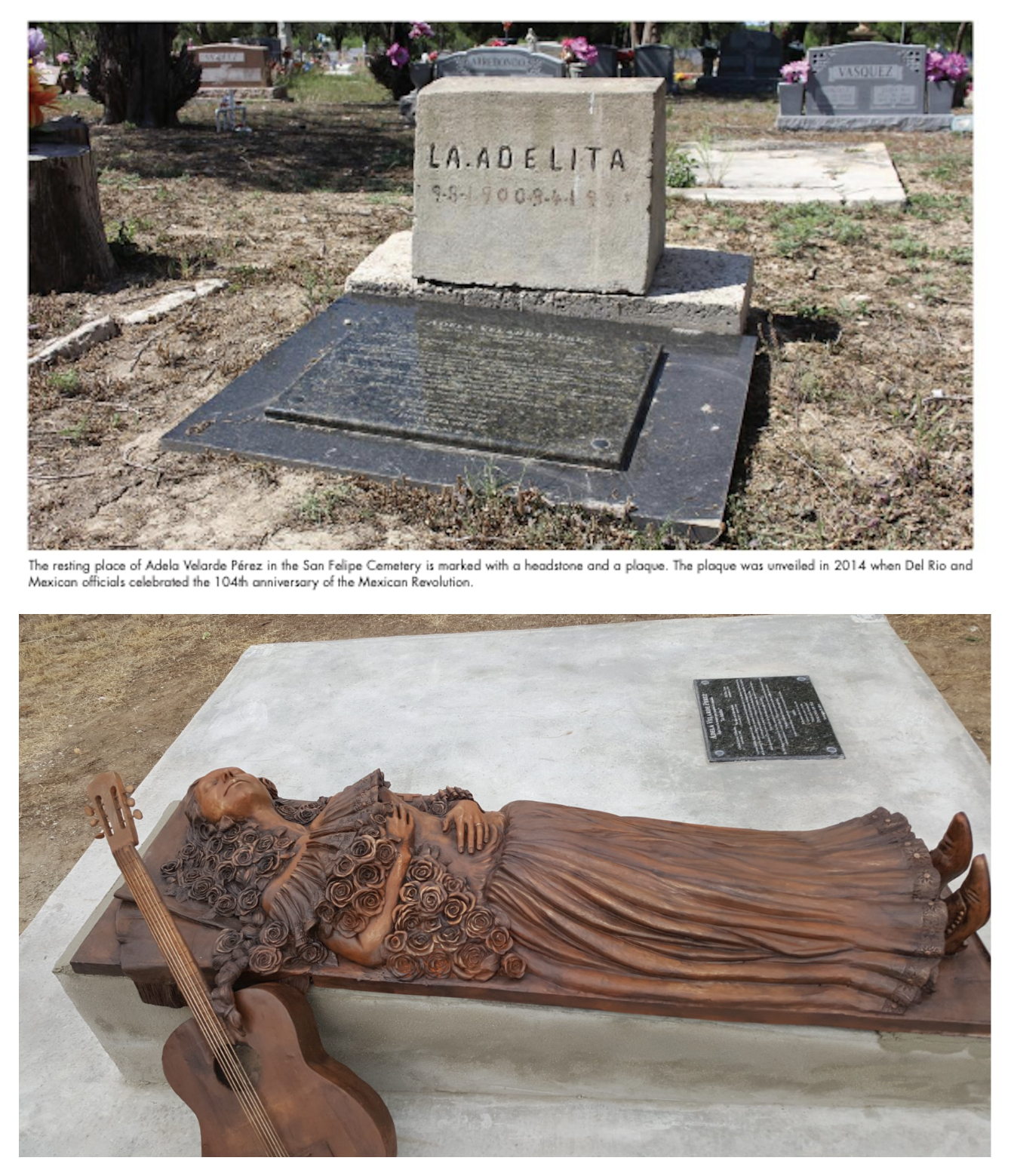

Velarde, who was officially recognized as a revolutionary veteran in 1941, is buried in Del Rio’s San Felipe Cemetery. Until recently, her grave was marked with a rustic, cement block crudely inscribed with her name and the relevant dates (Sep. 8, 1900 – Sep. 4, 1971), unartfully etched beneath it. It wasn’t until 43 years after her passing that the first formal official tribute was held at her gravesite, organized by Mexico’s Foreign Ministry and attended by some 100 people, according to Imagen Radio, a Mexican online news site. On that occasion in 2014, a plaque in her honor was placed at the foot of the tombstone, lying flat on the scruffy dirt plot.

The condition of the tomb was pathetic, whether the deceased Adela was the heroine of the corrido or not. The disgrace of her plain, pauper’s gravestone starkly underscored the historical neglect that haunted her fellow soldaderas.

Thankfully, the town of Del Rio has mobilized in recent years to revamp the gravesite and add a striking tribute. Organized as Friends of La Adelita – with the help of the business community, the local media, and the Mexican Consul in Del Rio – the group created a website and a Facebook page with the goal of raising $40,000 for a unique sculpture of the beloved Adelita.

Thankfully, the town of Del Rio has mobilized in recent years to revamp the gravesite and add a striking tribute. Organized as Friends of La Adelita – with the help of the business community, the local media, and the Mexican Consul in Del Rio – the group created a website and a Facebook page with the goal of raising $40,000 for a unique sculpture of the beloved Adelita.

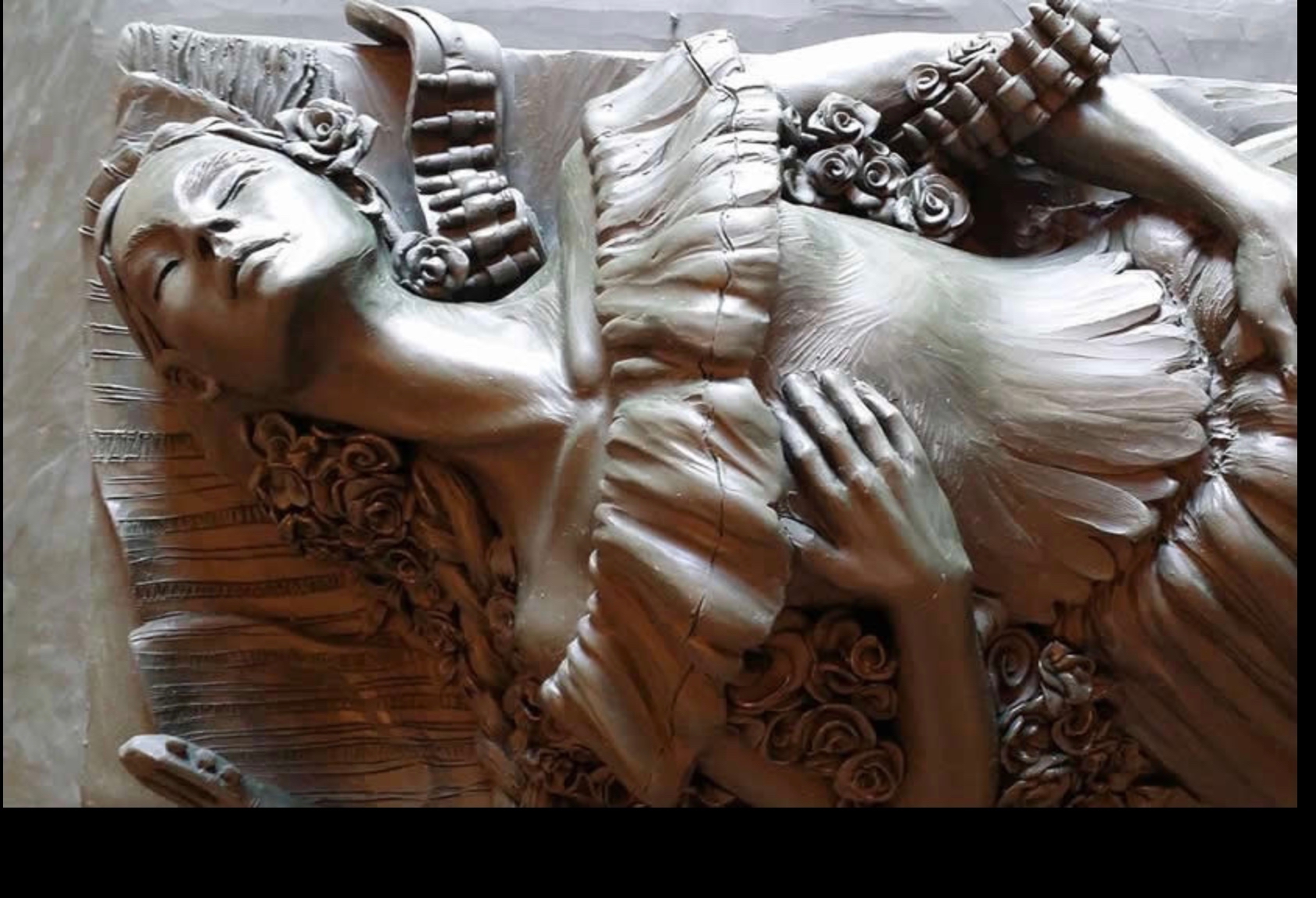

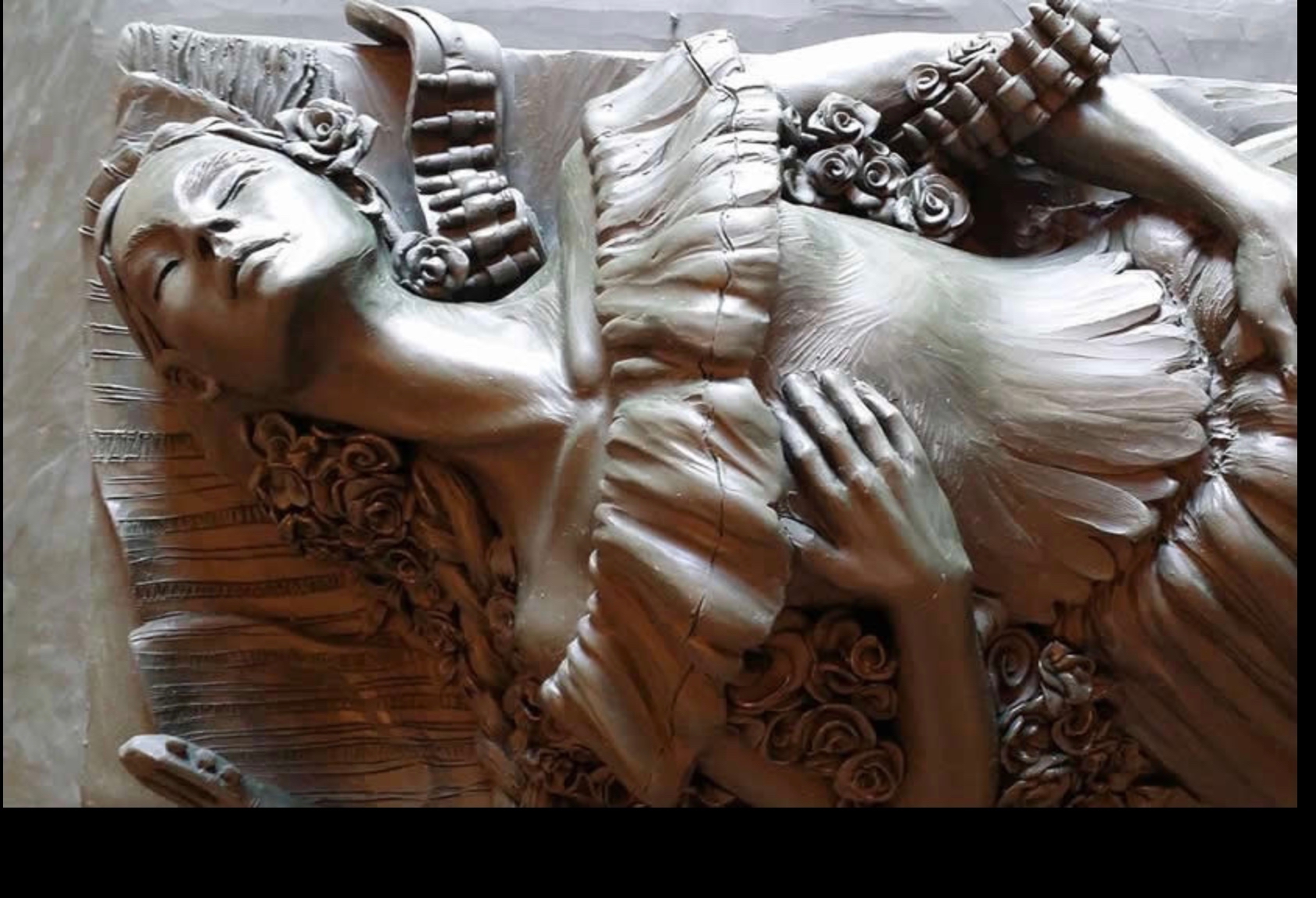

The stylized figure depicts the fallen soldadera lying in repose, draped in her traditional blouse and flowing skirt, shrouded in roses and a belt of bullets. It was created by sculptor Piti Luna of Saltillo, Coahuila.

The finished bronze figure, measuring more than eight feet long and weighing more than 550 pounds, was transported the 300 miles from Saltillo to Del Rio and unveiled at the cemetery on November 20, 2019, the 109th anniversary of the Revolution. The old eyesore of a headstone has been removed, replaced by a sleek concrete slab to accommodate the sculpture alongside the existing plaque.

The finished bronze figure, measuring more than eight feet long and weighing more than 550 pounds, was transported the 300 miles from Saltillo to Del Rio and unveiled at the cemetery on November 20, 2019, the 109th anniversary of the Revolution. The old eyesore of a headstone has been removed, replaced by a sleek concrete slab to accommodate the sculpture alongside the existing plaque.

The Adelita of All Trades

Regardless of La Adelita’s true identity, the individual names and stories of the vast majority of these female fighters may remain forever buried with them. Yet, their deeds as a group during the Revolution have been amply documented. In fact, these women played a critical role – actually multiple roles – in the violent upheaval that shaped modern Mexico.

"Without the soldaderas, there is no Mexican Revolution,” stated famed Mexican writer Elena Poniatowska. “They kept it alive and fertile, like the earth."

"Without the soldaderas, there is no Mexican Revolution,” stated famed Mexican writer Elena Poniatowska. “They kept it alive and fertile, like the earth."

The myth of La Adelita suggests that the women took up arms and fought for the revolution shoulder-to-shoulder with the men. While that is partially true, most of these female revolutionaries never fired a gun in battle.

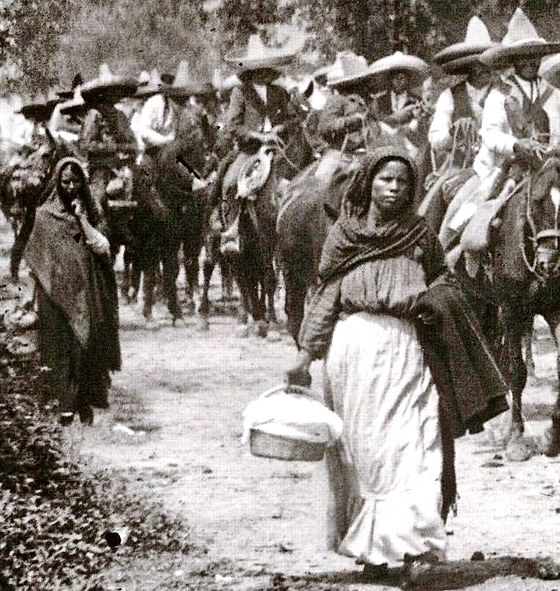

In fact, most joined the rebellion not by choice but out of fear and for lack of better options, according to historians. A substantial number of them were kidnapped from their hometowns to serve the men, either as companions, caretakers, or camp followers. Others joined the revolutionary ranks as a survival strategy, reckoning they were safer in the company of soldiers than in defenseless villages with the other women left behind.

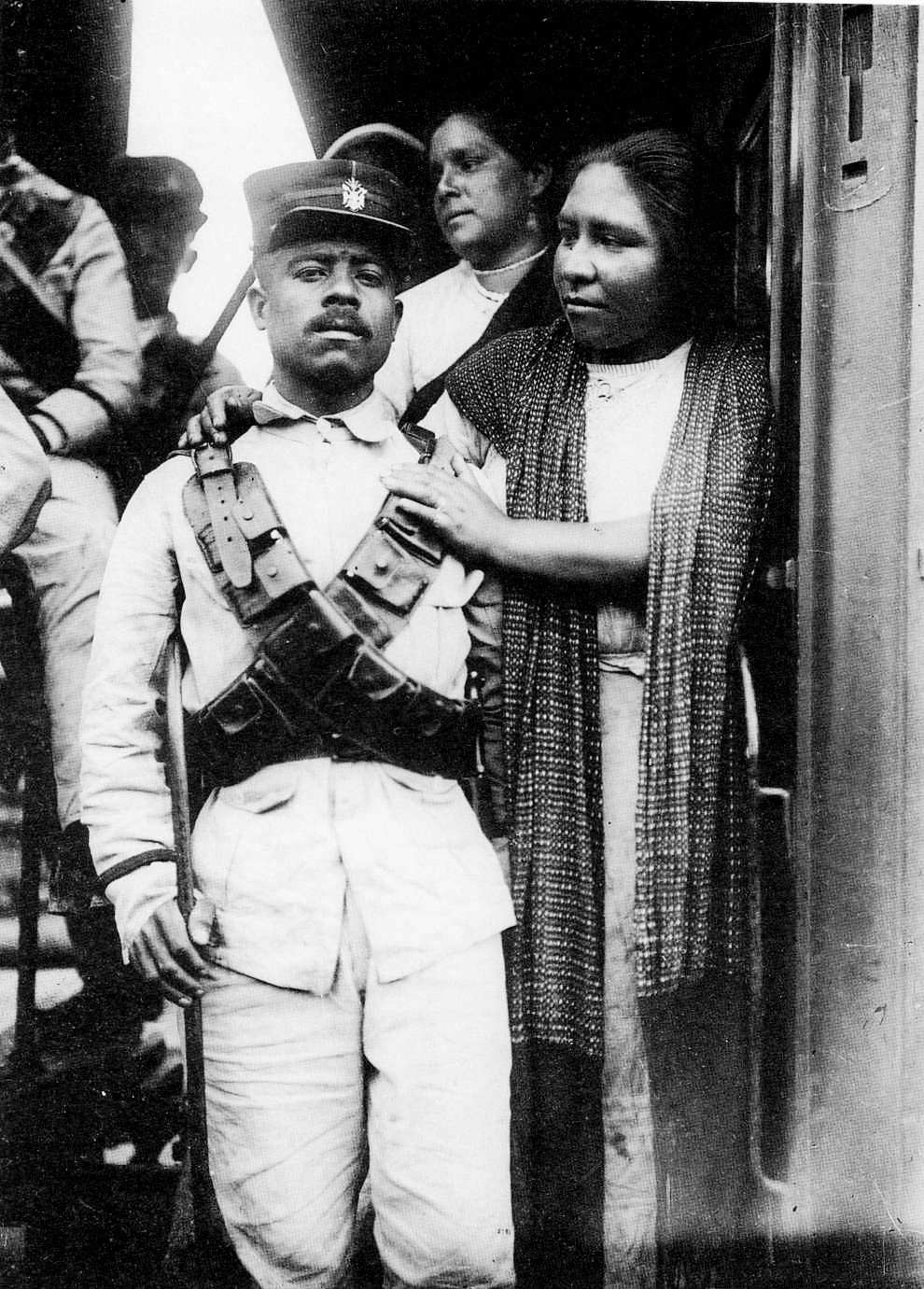

Still others joined to support their husbands, not on the battlefield but in military logistics: foraging for food, cooking meals, setting up tents, acquiring munitions, providing medical care. The women had to improvise in order to make up for regular supply lines that were inadequate or inconsistent, including for the ill-prepared and under-manned Mexican Army.

The women’s tasks were not as simple as everyday housekeeping. Despite their girlish, diminutive nickname, Las Adelitas had to be as strong and wily as survivalists. They learned to cook and make tortillas while riding on top of moving trains. In their constant hunt for food, they would enter towns after soldiers had left, loot stores for supplies, and search dead bodies for weapons and other valuables.

The soldaderas “hesitated at nothing to put together a meal,” writes Andrés Reséndez Fuentes in his essay, “Battleground Women: Soldaderas and Female Soldiers in the Mexican Revolution” (The Americas, April 1995). “The pressure to feed the troops was always great so the methods used to procure victuals were often extreme.”

The women were colloquially called “pateras,” or hoofers, because they would trudge ahead on foot to set up the next camp. Some did the heavy lifting even while pregnant, or while carrying their children along with pots and pans on their backs.

The women were colloquially called “pateras,” or hoofers, because they would trudge ahead on foot to set up the next camp. Some did the heavy lifting even while pregnant, or while carrying their children along with pots and pans on their backs.

“That they move as quickly as they do is a miracle,” wrote British journalist H. Hamilton Fyfe, a special correspondent for the London Times, in a dispatch on May 1, 1914. “Whatever the day’s march may be, they are always on the camping ground before the men arrive. They rig up shelters, they cook tortillas and frijoles (maize cakes and beans), they make coffee. You see them mending their husbands’ coats, washing their shirts, roughly tending flesh wounds. Without these soldaderas the army could not move.”

When it came to tending to the sick and wounded, the role of Las Adelitas as battlefield nurses was critical. Military medical care, like basic provisions, was not always available in an organized, reliable fashion. For some fallen soldiers, these women provided their only chance for survival.

If a hospital was nearby, the women were charged with transporting the injured by pulling them in oxcarts. When soldiers died, they carted the cadavers to burial.

Beyond cooking, cleaning, and nursing the sick, however, a few daring women carried out dangerous cloak-and-dagger assignments.

Some acted as spies, infiltrating enemy ranks disguised as camp followers to gather intel on the other side. Others personally delivered urgent messages among their own top commanders. Still others smuggled weapons and ammunition, especially from the U.S., exploiting the chauvinism that degraded their value. Since they were perceived as harmless, they were rarely suspected as smugglers, according to Reséndez. They hid ammunition under their skirts, sometimes hanging hundreds of rounds from belts that dropped to their knees.

Although Las Adelitas have come to represent the revolutionary spirt, not all of them fought on the rebel side. Many joined the Federales, the government forces fighting to put down the rebellion. The women were needed by both sides, not only for their support functions, but for what historians call “promoting social cohesion.”

Although Las Adelitas have come to represent the revolutionary spirt, not all of them fought on the rebel side. Many joined the Federales, the government forces fighting to put down the rebellion. The women were needed by both sides, not only for their support functions, but for what historians call “promoting social cohesion.”

In the context of the Mexican Revolution, “promoting social cohesion” meant one thing: keeping the men satisfied.

Even reluctant generals and macho revolutionaries who openly opposed the presence of women in the ranks – for tactical, philosophical, or misogynistic reasons – came to see that the so-called fair sex was essential to the fight. When women and children were allowed to accompany the fighting forces, morale went up and rates of rape and desertion went down.

The extensive use of trains to move troops, especially in the North, made it much easier for women and children to accompany men to the battlefields. While the men and horses travelled inside the trains, the women rode on top or stood sandwiched in the spaces between boxcars. Some even hung by ropes under the trains, or clutched precariously to cowcatchers, the V-shaped metal structures on the front of locomotives used to clear tracks and prevent derailments.

Observers, both foreign and domestic, were impressed by the way Las Adelitas performed under extremely arduous circumstances. In her well- researched honors thesis, historian Maria Leland noted that the women carried out their wartime duties with “tremendous ingenuity and resource.”

Their value and valor on the battlefield were not lost on one foreign observer, Ivar Thord-Gray, a Swedish mercenary who had joined Villa's forces.

“The women camp followers had orders to remain behind, but hundreds of them, hanging onto the stirrups, followed their men on the road for a while,” he wrote in 1911. “Some other women carrying carbines, bandoleers, and who were mounted, managed to slip into the ranks and came with us. These took their places in the firing lines and withstood hardship and machine gun fire as well as the men. They were a brave, worthy lot. It was a richly picturesque sight, but the complete silence, the stoic yet anxious faces of the women was depressing, as it gave the impression that all were going to a tremendous funeral, or their doom.”

̶ Agustín Gurza

Continue to "La Adelita Part 2, From Pop Commodity to Historic Hero"

Blog Category

Tags

Images