Los Lobos, Ritchie Valens, and the Day the Music Died

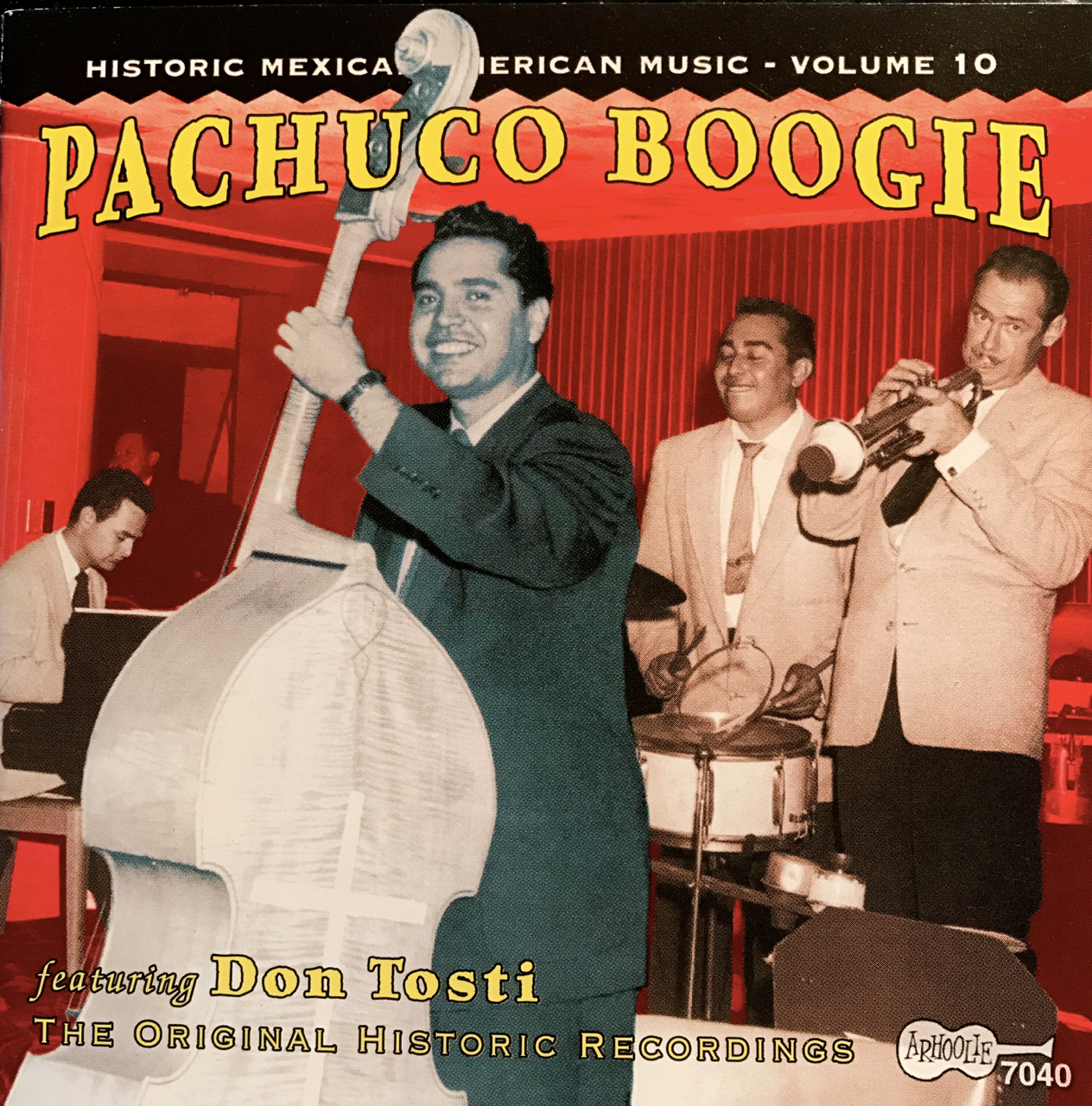

The Frontera Collection specializes in Mexican American music, especially the early, rural formats of norteño and conjunto groups from the first half of the 20th century. But beginning in the 1970s, new styles produced b y young Mexican Americans in large urban centers emerged, fusing traditional and modern genres. In Los Angeles the most influential and critically acclaimed band from that era was Los Lobos del Este de Los Angeles.

y young Mexican Americans in large urban centers emerged, fusing traditional and modern genres. In Los Angeles the most influential and critically acclaimed band from that era was Los Lobos del Este de Los Angeles.

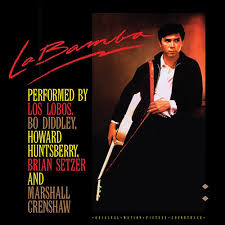

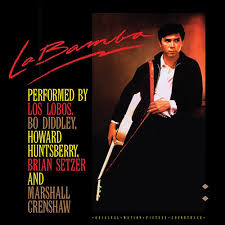

The East L.A. quartet hit its peak of popularity with the soundtrack to the 1987 biopic La Bamba, which tells the tragic life story of Ritchie Valens, the Chicano rock pioneer. This month marks the 58th anniversary of Valens’s death, along with two other early rock stars, Buddy Holly and The Big Bopper. While on a winter tour in Iowa in 1959, the trio perished in a plane crash, an event memorialized by singer-songwriter Don McLean as “the day the music died” from his 1971 hit “American Pie.” Holly, a respected pioneer of the emerging rockabilly scene, was the most famous victim. But for Chicanos in California, the loss of Valens, born Richard Steven Valenzuela, was a heavy blow because the young up-and-comer symbolized a cultural breakthrough in a musical field dominated by blacks and whites. Valens is considered the country’s first major Mexican-American rock star, preceding Carlos Santana by a decade, and predating the crossover success of Los Lobos by 20 years.

Many young Chicanos today are more likely to remember Valens from the movie, starring Lou Diamond Phillips and featuring a rousing soundtrack by Los Lobos that was a worldwide smash. The album sold 2 million copies in the U.S. alone, and the title tune went to No. 1 on Billboard’s Hot 100. The film’s cover version earned Los Lobos a nomination for Song of the Year at the 1988 Grammy Awards. And their festive “La Bamba” video – with its swirling, twirling images from a live performance intertwined with snappy film clips – also won a 1988 MTV Video Music Award.

Many young Chicanos today are more likely to remember Valens from the movie, starring Lou Diamond Phillips and featuring a rousing soundtrack by Los Lobos that was a worldwide smash. The album sold 2 million copies in the U.S. alone, and the title tune went to No. 1 on Billboard’s Hot 100. The film’s cover version earned Los Lobos a nomination for Song of the Year at the 1988 Grammy Awards. And their festive “La Bamba” video – with its swirling, twirling images from a live performance intertwined with snappy film clips – also won a 1988 MTV Video Music Award.

The movie, of course, tells the story of the fateful plane crash from Valens’ perspective. Tormented by a fear of flying, the young star won a coin toss that put him on the doomed plane during a blinding snow storm. The film, directed by Luis Valdez of Zoot Suit fame, reveals the singer’s working-class background, conflicts with his older brother (played in a breakout role by Esai Morales), and his crush on a high school sweetheart that inspired the hit ballad “Donna.”

In death, sadly, Valens earned a far more lasting legacy than he may have otherwise enjoyed. He was just 17 in the spring of 1958 when he was discovered by L.A. record producer, Bob Keane, intrigued by buzz about the Chicano rocker kids were calling The Little Richard of San Ferna ndo. That summer, Valens released his first hit single, “Come On Let’s Go,” issued by Keane’s Del-Fi Records. That was soon followed by another single with hits on both sides, “Donna” backed by “La Bamba.”

ndo. That summer, Valens released his first hit single, “Come On Let’s Go,” issued by Keane’s Del-Fi Records. That was soon followed by another single with hits on both sides, “Donna” backed by “La Bamba.”

Amazingly, those were the only two recordings Valens would see released during his lifetime. He was still 17 when he died early the following year, his lightening recording career having lasted just 10 months. His first studio album, “Ritchie Valens,” was released posthumously and peaked at No. 23 on the Billboard album chart.

In retrospect, we have the impression that “La Bamba” was Valens’ biggest hit, but far from it, accor ding to Billboard chart archives. The singer’s twangy adaptation of the jarocho classic from Veracruz was actually the B-side of the single, and it peaked at No. 22. The A-side, the ode to Donna, was his biggest hit, reaching No. 2 on the Hot 100 the week of February 28, 1959.

ding to Billboard chart archives. The singer’s twangy adaptation of the jarocho classic from Veracruz was actually the B-side of the single, and it peaked at No. 22. The A-side, the ode to Donna, was his biggest hit, reaching No. 2 on the Hot 100 the week of February 28, 1959.

Both of the songs took off in sales only after the singer had died. Before that, they had been floating around the bottom half of the rankings for months. His first hit, “Come On Let’s Go,” had peaked at No. 42 in November of 1958, after 13 weeks on the chart. That early success may have been quite a shot in the arm for the nascent barrio star, but it was hardly setting the music industry on fire at the time.

So the truth is that the Chicano version of “La Bamba” did not become an international smash until Los Lobos re-recorded it for the movie. By then, Valens had been dead for almost 30 years. The Lobos track hit No. 1 in the summer of 1987, in the wake of the film’s success, and they followed up with a version of Valens’s “Come On Let’s Go,” also from the soundtrack, which peaked at No. 21 in the fall of that year.

Los Lobos, however, did not have to wait for the movie release to discover Ritchie Valens, or jarocho music for that matter. Before they broke through with their Chicano blues/rock fusion, they were “Just Another Band from East L.A.,” to borrow the subtitle of  their eponymous 1978 debut album. From the start, they were playing música jarocha and other Mexican folks styles, especially norteño music with accordion.

their eponymous 1978 debut album. From the start, they were playing música jarocha and other Mexican folks styles, especially norteño music with accordion.

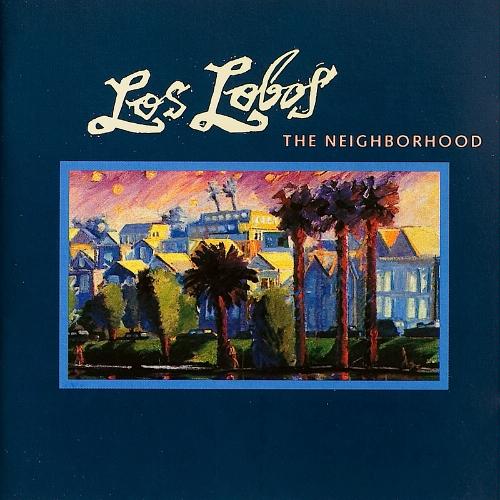

Over the years, Los Lobos have been acclaimed for their crossover album projects, much more than hit singles, which were rare for them. The Frontera Collection includes the complete cassette recording of their 1990 album The Neighborhood. But their hit recording of “La Bamba” is missing from the archives.

Among all the songs in the collection, however, “La Bamba” ranks No. 4 on the list of Top 10 most recorded tunes, according to my 2012 book about the Frontera archives. I found almost 90 recordings of the adaptable classic, from the most traditional, to one with a Tex-Mex twist, and a take by a romantic trio with refined cosmopolitan harmonies.

Unfortunately, the original Valens recording on Del-Fi Records is not included here, either. Instead, we find a scratchy, undated, 45-rpm on Eric Records, a New Jersey-based label specializing in re-issues. Just like the original Del-Fi release, this version also has “Donna” on the flip side. But it’s hard to tell if these are the identical tracks released by Del-Fi in 1958. The Eric label also released the two Valens sides on a 27-track compilation of oldies, titled Hard To Find Jukebox Classics 1959: Teen Pop Gold. The recording of “La Bamba” on that Eric album includes a notation: “rare STEREO single version.” (By the way, the compilation also includes “Chantilly Lace,” the big hit by The Big Bopper, the third doomed singer in the 1959 crash.)

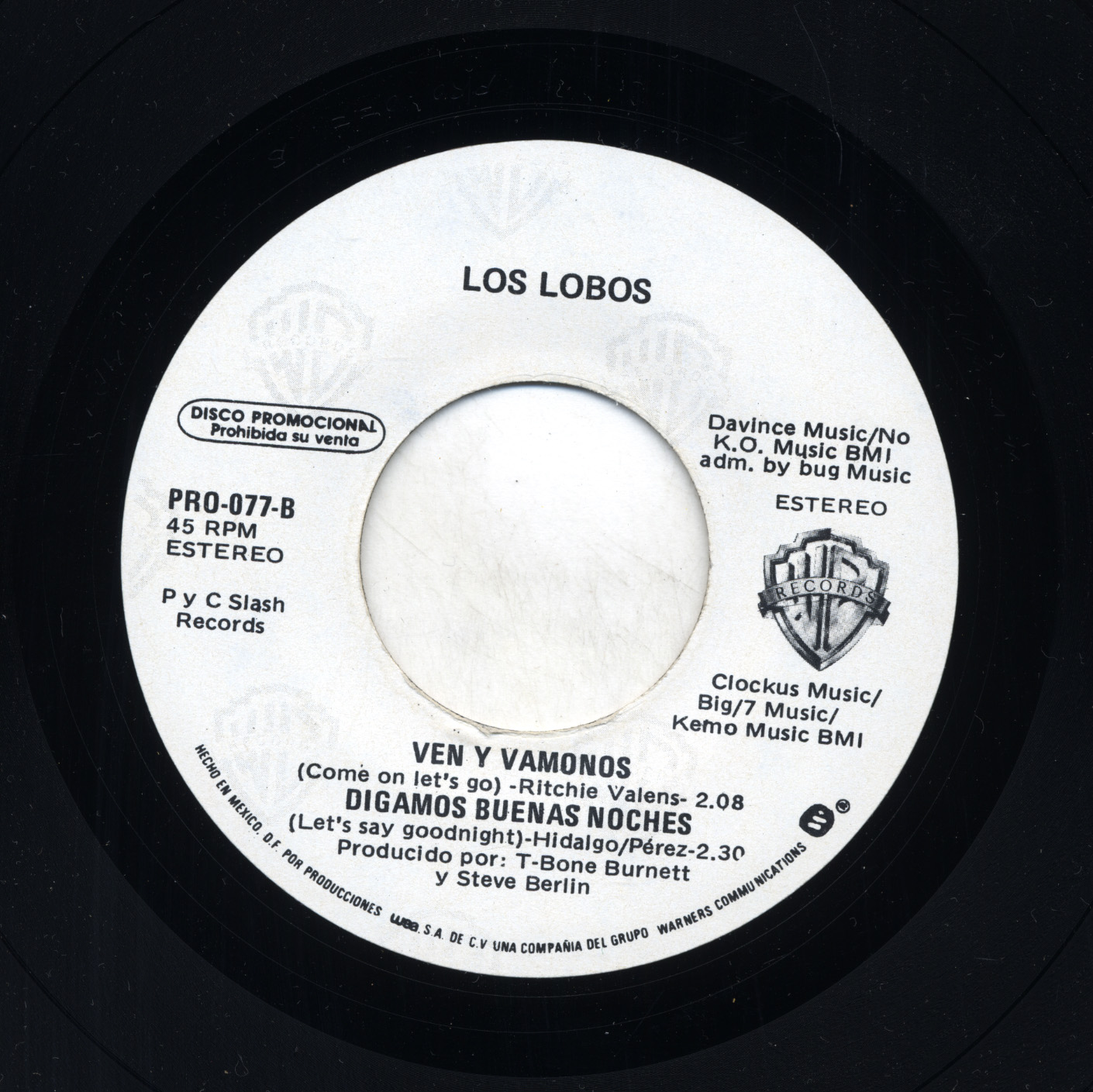

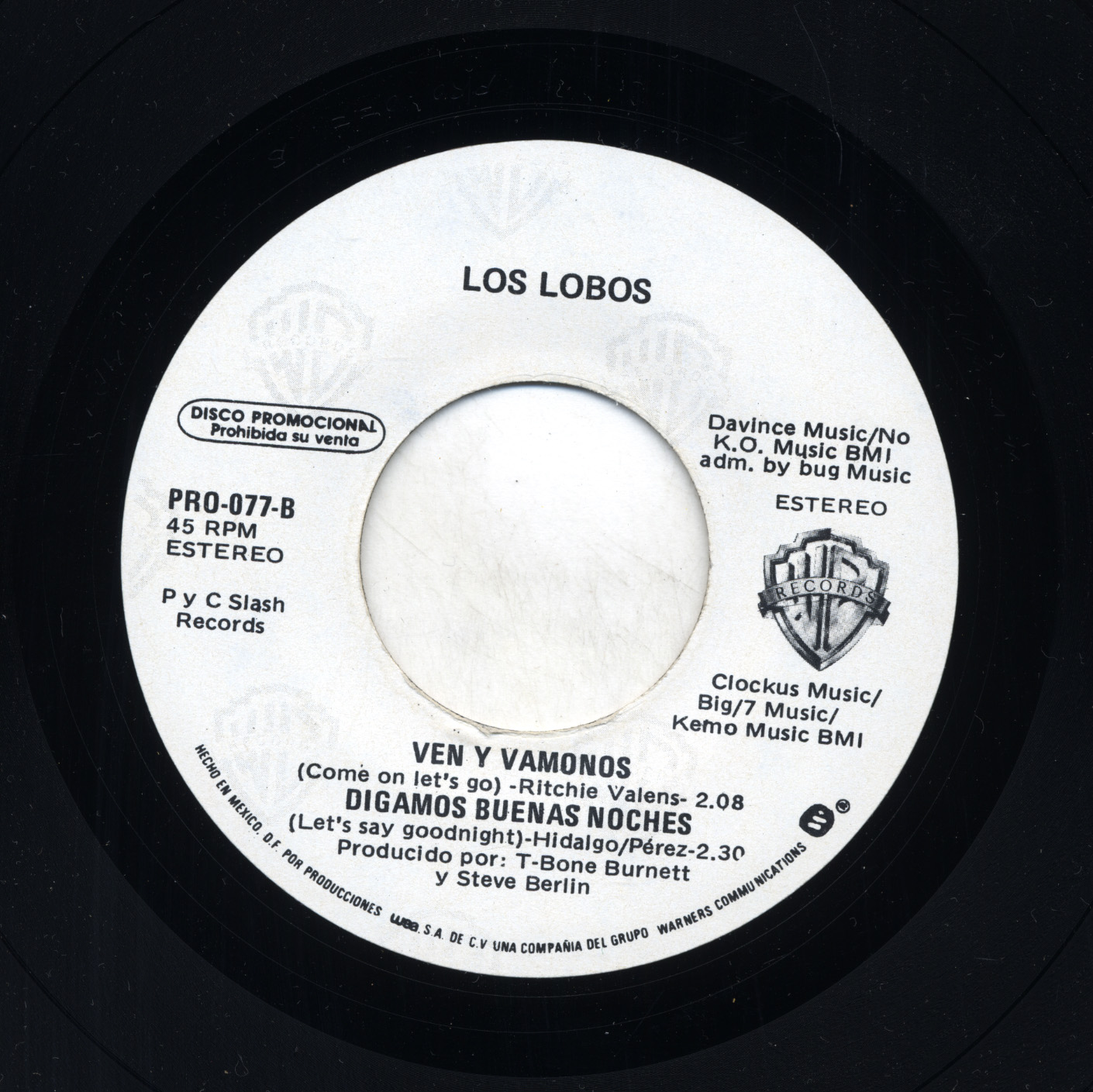

The Frontera Collection includes one other recording of note from Los lobos. It’s a 4-track EP with songs from their debut crossover record, ... And a Time to Dance, released in 1983 by Warner Bros. on the Slash label. What’s interesting is that this is a rare Mexican release of those tracks, including a song titled in Spanish “Ven Y Vamonos.” The translation in parentheses identifies it as that original Ritchie Valens hit, “Come On Let’s Go.”

The Frontera Collection includes one other recording of note from Los lobos. It’s a 4-track EP with songs from their debut crossover record, ... And a Time to Dance, released in 1983 by Warner Bros. on the Slash label. What’s interesting is that this is a rare Mexican release of those tracks, including a song titled in Spanish “Ven Y Vamonos.” The translation in parentheses identifies it as that original Ritchie Valens hit, “Come On Let’s Go.”

That recording, coming five years before the movie, provides proof that Los Lobos were already hip to the Valens legacy. They well knew the cultural importance of seeing a local Mexican American on the mainstream pop charts. And their success, in turn, allowed them to put a spotlight on the fleeting success of an Americanized Chicano kid, who died so young but left an enduring inspiration for generations to come.

-- Agustín Gurza

Tags

Images