the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center,

the Arhoolie Foundation,

and the UCLA Digital Library

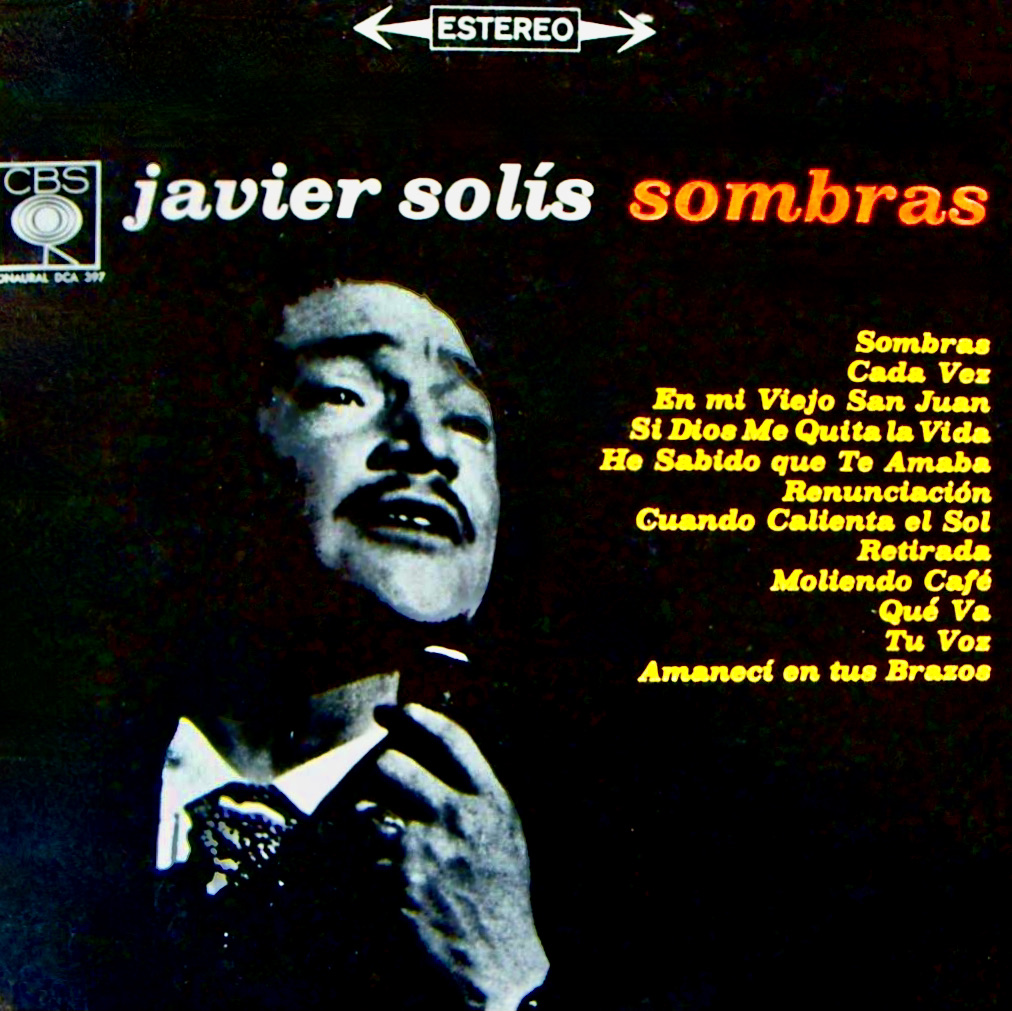

The bolero may not be what it used to be, but as they say in show business, it had a great run. Plus, a great revival or two.

In the first installment of my three-part series on the bolero, I offered an overview of the romantic genre and highlighted songs I had learned from my parents as a ch

In the first installment of my three-part series on the bolero, I offered an overview of the romantic genre and highlighted songs I had learned from my parents as a ch

In late 2019, Los Tigres del Norte released a live album that marked a milestone in their storied career. The two-CD set captured the band’s historic performance at Folsom State Prison, staged to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the legendary concert by country singer Johnny Cash at the same notorious penitentiary. The Tigres event was also filmed for a Netflix documentary, released along with the album on Mexican Independence Day.

In late 2019, Los Tigres del Norte released a live album that marked a milestone in their storied career. The two-CD set captured the band’s historic performance at Folsom State Prison, staged to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the legendary concert by country singer Johnny Cash at the same notorious penitentiary. The Tigres event was also filmed for a Netflix documentary, released along with the album on Mexican Independence Day.

The music business is bloated with award shows that serve as mass marketing events, meant to magnify artist exposure and, hopefully, boost record sales. But there are certain honors that have a timeless impact beyond immediate commercial gain. These are tributes that, rather than publicity, bestow prestige on artists and serve to enhance the legacy of their recordings.

The music business is bloated with award shows that serve as mass marketing events, meant to magnify artist exposure and, hopefully, boost record sales. But there are certain honors that have a timeless impact beyond immediate commercial gain. These are tributes that, rather than publicity, bestow prestige on artists and serve to enhance the legacy of their recordings. Many countries have iconic images and unofficial anthems that capture the essence of the national spirit. In the United States, there’s the high-stepping tune “Yankee Doodle Dandy.” Sometimes, just a few words are enough to evoke a familiar cause and its historic significance. Rosie the Riveter. The suffragettes. The colonial minutemen. We can easily picture them in our mind’s eye, with any attendant nostalgia or national pride.

Many countries have iconic images and unofficial anthems that capture the essence of the national spirit. In the United States, there’s the high-stepping tune “Yankee Doodle Dandy.” Sometimes, just a few words are enough to evoke a familiar cause and its historic significance. Rosie the Riveter. The suffragettes. The colonial minutemen. We can easily picture them in our mind’s eye, with any attendant nostalgia or national pride.

In Mexico, one iconic female figure embodies that cultural and historic significance. La Adelita, a mythical composite persona, represents the thousands of unknown women who joined the Revolution of 1910, playing various key roles in the popular uprising that overthrew the Euro-centric dictatorship of Porfirio Diaz.

Music lovers who explore the Frontera Collection for their favorite hit songs may be occasionally disappointed or even perplexed. For example, how could a musical archive dedicated to Mexican American music fail to contain the celebrated albums by Eydie Gorme and Trio Los Panchos? Those Colombia titles were huge hits among Mexican Americans in the 1960s and have remained standards ever since.

Music lovers who explore the Frontera Collection for their favorite hit songs may be occasionally disappointed or even perplexed. For example, how could a musical archive dedicated to Mexican American music fail to contain the celebrated albums by Eydie Gorme and Trio Los Panchos? Those Colombia titles were huge hits among Mexican Americans in the 1960s and have remained standards ever since.

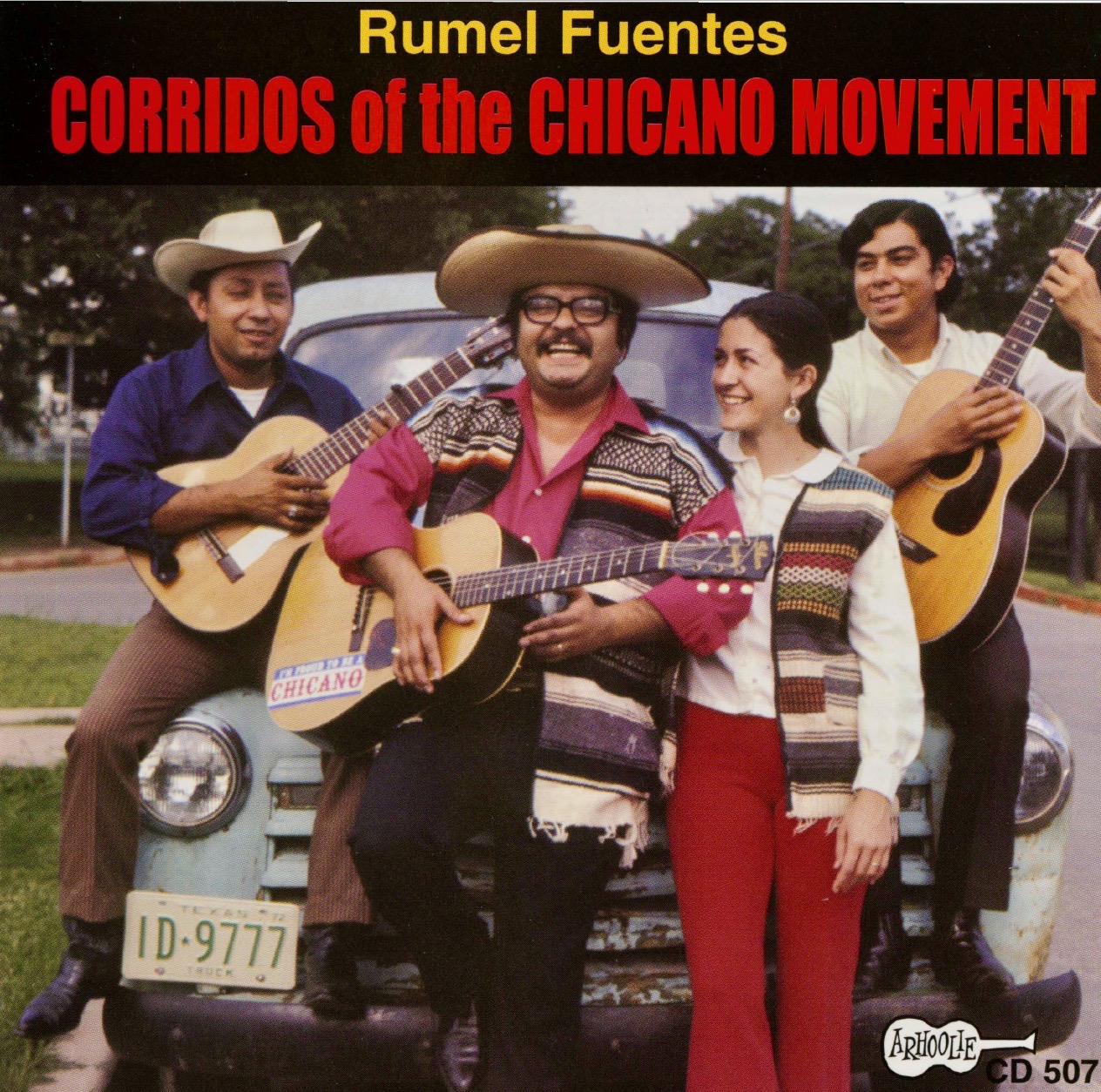

This year marked the 50th anniversary of the National Chicano Moratorium, the massive anti-war march in East Los Angeles held on August 29, 1970. The milestone inspired major media retrospectives on the impact of this galvanizing demonstration, citing inroads made by Chicanos in politics, higher education, journalism, and the arts.

This year marked the 50th anniversary of the National Chicano Moratorium, the massive anti-war march in East Los Angeles held on August 29, 1970. The milestone inspired major media retrospectives on the impact of this galvanizing demonstration, citing inroads made by Chicanos in politics, higher education, journalism, and the arts.

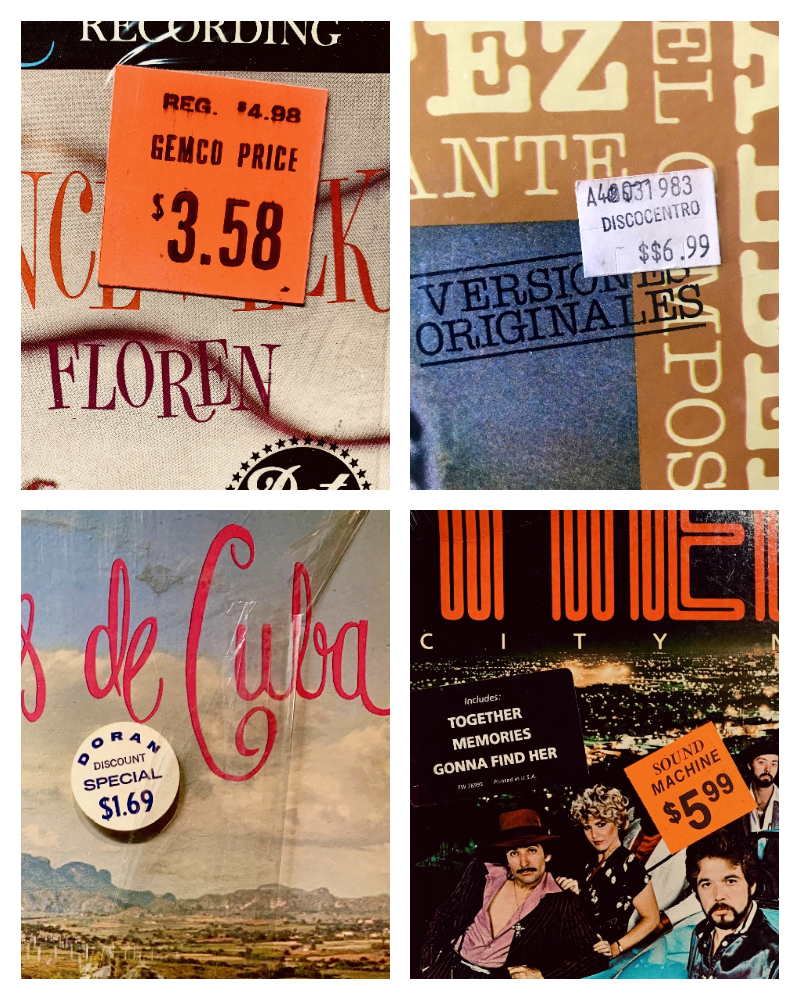

A true record collector is more than a mere music aficionado. Collectors are also part historians, part archivists, part treasure hunters, and part detectives. They look at records like archeological artifacts, analyzing them for clues to a particular culture and way of life, in a specific time and place.

A true record collector is more than a mere music aficionado. Collectors are also part historians, part archivists, part treasure hunters, and part detectives. They look at records like archeological artifacts, analyzing them for clues to a particular culture and way of life, in a specific time and place.

Even the common price sticker, for example, can offer a tantalizing glimpse into the life of a record, especially one that keeps circulating, passed lovingly (one hopes) from hand to hand. It tells you where that record made a stop on its road from manufacturer to market. And it allows you to imagine the details of that retail sojourn.

The recording career of Margarita La Chaparrita was modest and short-lived but remarkable, nevertheless. After struggling through a series of traumatic relationships and raising seven children with meager resources, the late-blooming performer decided to start her own band in the midst of middle age, when most other mothers are winding down to retirement.

The recording career of Margarita La Chaparrita was modest and short-lived but remarkable, nevertheless. After struggling through a series of traumatic relationships and raising seven children with meager resources, the late-blooming performer decided to start her own band in the midst of middle age, when most other mothers are winding down to retirement.

“I remember always hearing her singing in her kitchen while she was making dinner and I knew that music was a secret passion of hers,” said her daughter, Diana Benavides-Arredondo. “Once she finished raising all her children, she went for it. When she was in her late 40s and found herself an empty-nester, she started a small Mexican band and Margarita La Chaparrita y Su Conjunto was born.”

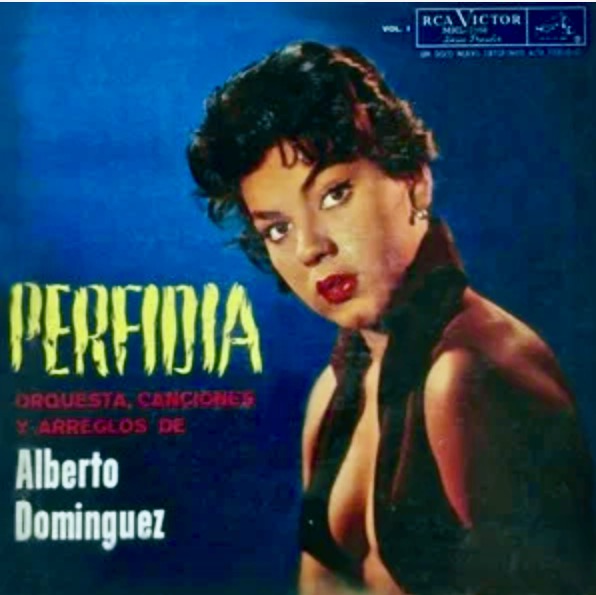

“Perfidia” has stood as one of the most cherished and enduring songs in the Latin American songbook. Composed more than 80 years ago by Mexico’s Alberto Dominguez, it is enshrined as one of those timeless standards that continues to inspire artists and resonate with music lovers, young and old.

“Perfidia” has stood as one of the most cherished and enduring songs in the Latin American songbook. Composed more than 80 years ago by Mexico’s Alberto Dominguez, it is enshrined as one of those timeless standards that continues to inspire artists and resonate with music lovers, young and old.

Recently, I heard the song’s memorable melody which watching a new movie on Netflix, the Spanish film Vivir Dos Veces (2019), by Barcelona-born director Maria Ripoll. The movie is about an aging math professor named Emilio, a lonely widower who finds himself sinking into the terrifying early stages of dementia. It explores how he and his small family, a take-charge daughter and precocious granddaughter, handle the crisis.

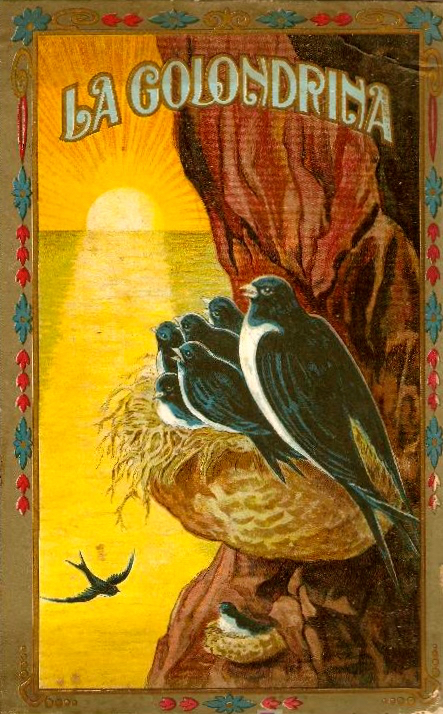

During the funeral services of Mexico’s beloved pop singer José José this month, a tune was played that surely touched the hearts of most Mexicans, especially those watching from afar. The song is titled “La Golondrina” (The Swallow), a veritable hymn that for more than a century has added a note of nostalgia to moments of loss, departure, and exile.

During the funeral services of Mexico’s beloved pop singer José José this month, a tune was played that surely touched the hearts of most Mexicans, especially those watching from afar. The song is titled “La Golondrina” (The Swallow), a veritable hymn that for more than a century has added a note of nostalgia to moments of loss, departure, and exile.

Part of the frustration of building a musical archive like the Frontera Collection is the lack of reliable and readily available information for every recording. Key data – such as release dates, accompaniment, musician credits, and studio locations – is often missing or simply beyond the reach of researchers.

Part of the frustration of building a musical archive like the Frontera Collection is the lack of reliable and readily available information for every recording. Key data – such as release dates, accompaniment, musician credits, and studio locations – is often missing or simply beyond the reach of researchers.

Until her recent death, singer Rita Vidaurri (1924–2019) stood as the last surviving star of what is considered a Golden Age of female vocalists from San Antonio, during the 1930s and ’40s. Like her contemporaries Eva Garza (1917-1966), Rosita Fernandez (1919-2006), and Lydia Mendoza (1916-2007), Vidaurri relied on the Alamo City’s vibrant Mexican-American music scene to launch an international career, sharing world stages with superstars such as Nat “King” Cole, Pedro Infante, and Celia Cruz.

Until her recent death, singer Rita Vidaurri (1924–2019) stood as the last surviving star of what is considered a Golden Age of female vocalists from San Antonio, during the 1930s and ’40s. Like her contemporaries Eva Garza (1917-1966), Rosita Fernandez (1919-2006), and Lydia Mendoza (1916-2007), Vidaurri relied on the Alamo City’s vibrant Mexican-American music scene to launch an international career, sharing world stages with superstars such as Nat “King” Cole, Pedro Infante, and Celia Cruz.

Los Donneños, a duet formed in the late 1940s in the Rio Grande Valley of South Texas, were pioneers in the evolution of norteño music during the 1950s. They went on to become one of the first Tex-Mex acts to find major success on both sides of the border.

The historic duet was formed by two musicians, Ramiro Cavazos on guitar and Mario Montes on accordion. They both hailed from the Mexican border state of Nuevo Leon, but they met only after moving to the U.S. side of the Rio Grande.

Stay informed on our latest news!