The Eternal Bolero, Part 1: Love Songs that Endure for Decades

The bolero is one of the top song styles from Latin America, as ubiquitous as the tango, the mambo, or the bossa nova. Among the genres identified in the Frontera Collection, the romantic bolero ranks No. 2, currently with more than 17,500 entries. That includes more than 70 sub-genres, such as bolero ranchero, bolero mambo, bolero rítmico, and criolla bolero, an outdated style featured on just three 78-rpm recordings.

The bolero is one of the top song styles from Latin America, as ubiquitous as the tango, the mambo, or the bossa nova. Among the genres identified in the Frontera Collection, the romantic bolero ranks No. 2, currently with more than 17,500 entries. That includes more than 70 sub-genres, such as bolero ranchero, bolero mambo, bolero rítmico, and criolla bolero, an outdated style featured on just three 78-rpm recordings.

Most people in the U.S., regardless of cultural background, have heard a bolero at some point, even if they can’t specifically identify a song as such. Some boleros have become major hits with English lyrics.

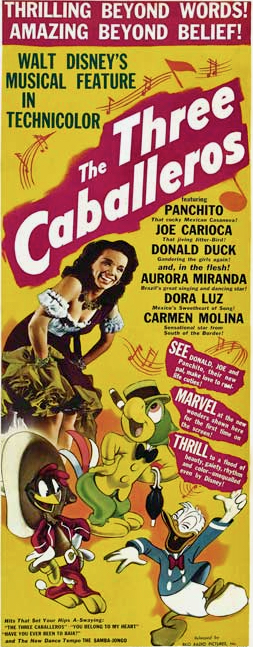

Agustín Lara’s world-renowned bolero “Solamente Una Vez,” written in 1941, was recorded four years later by Bing Crosby with Xavier Cugat as "You Belong to My Heart" and became a Top 10 hit for Decca Records. It was featured in the 1944 Disney film The Three Caballeros singing to Donald Duck, and was also on the soundtrack to the 2004 comedy Napoleon Dynamite, in a Spanish version by Trío Los Panchos.

María Grever’s 1934 classic, “Cuando Vuelva a Tu Lado," became a Top 10 smash in 1959 for Dinah Washington in her English rendition, “What a Diff'rence a Day Makes."

Many boleros have become standards in the Latin American Songbook. I have previously explored two of the most popular tunes on this blog as featured songs – “Perfidia” by Alberto Dominguez and “Sabor a Mí” by Alvaro Carrillo.

The bolero, as a song genre, should be distinguished from the 18th century Spanish dance of the same name, which formed the basis of Ravel’s famous “Boléro,” which premiered at the Paris Opera in 1928. Almost 100 years earlier, classical composer Frédéric Chopin wrote a piano work also titled “Boléro,” but with ambiguous origins sometimes attributed to the composer’s Polish roots, prompting the description boléro à la polonaise.

The modern bolero emerged in the late 18th century as a song style in Cuba, arising from the old trova tradition, which at times set poetry to music. “Tristezas” is considered the first bolero ever written and is widely attributed to the popular trova artist José "Pepe" Sánchez (1856–1918) from Santiago de Cuba, near Guatánamo. Located on Cuba’s eastern coast, Santiago was also the cradle of the seminal Afro-Cuban dance style known as son, a cornerstone of what later became salsa music. Early on, the bolero and the son blended in a hybrid style popularized by the legendary Trío Matamoros, catapulting the music to international fame.

In the 1940s, the bolero took root in Mexico which became the leading exponent of the genre through the 1950s and ’60s. The superstars of the era, propelled by Mexico’s powerhouse film industry, were bolero singers and songwriters, including Agustín Lara, Pedro Vargas, Gabriel Ruiz, Toña La Negra, and a talented transplant from Chile, Lucho Gatica. Others carried the romantic torch into the 1960s and ’70s, including bolero ranchero singer Javier Solis, mariachi megastar Vicente Fernandez, alluring vocalist Chelo Silva, and Mexico’s most important bolero composer of the modern era, Armando Manzanero.

The genre had top exponents from other countries, most notably Rafael Hernandez of Puerto Rico, Alfredo Sadel of Venezuela, Julio Jaramillo of Ecuador, and Libertad Lamarque of Argentina.

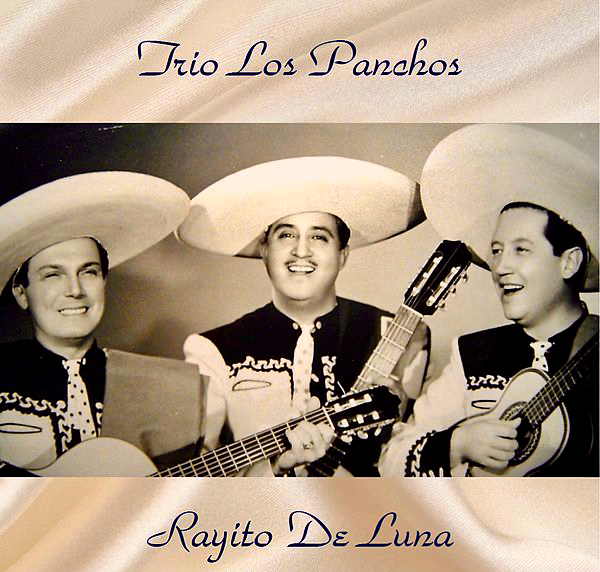

But Mexico remained the focal point, especially after Trío Los Panchos established the preferred bolero format of three-part harmonies and three guitars, with light percussion backing. Founded in New York in 1944, Los Panchos became the quintessential interpreters of romantic songs in the post-war era, recordings dozens of albums for Columbia Records and performing in concert worldwide. They gained new fans in the U.S. with a still popular series of recordings featuring vocalist Eydie Gormé, replete with a classic bolero repertoire.

While doing research for this album, I learned an important fact. The requinto, a distinctive guitar tuned higher and built smaller than normal, was created by Alfredo Gil, a founding member of Los Panchos. The requinto has been an essential component of trios ever since, employed for the genre’s trademark bright intros and nimble-fingered solos. Of course, the bolero is also versatile and suited to a variety of instrumentation, including a solo vocalist with guitar, a nightclub combo with piano, or a full orchestra with strings and horns.

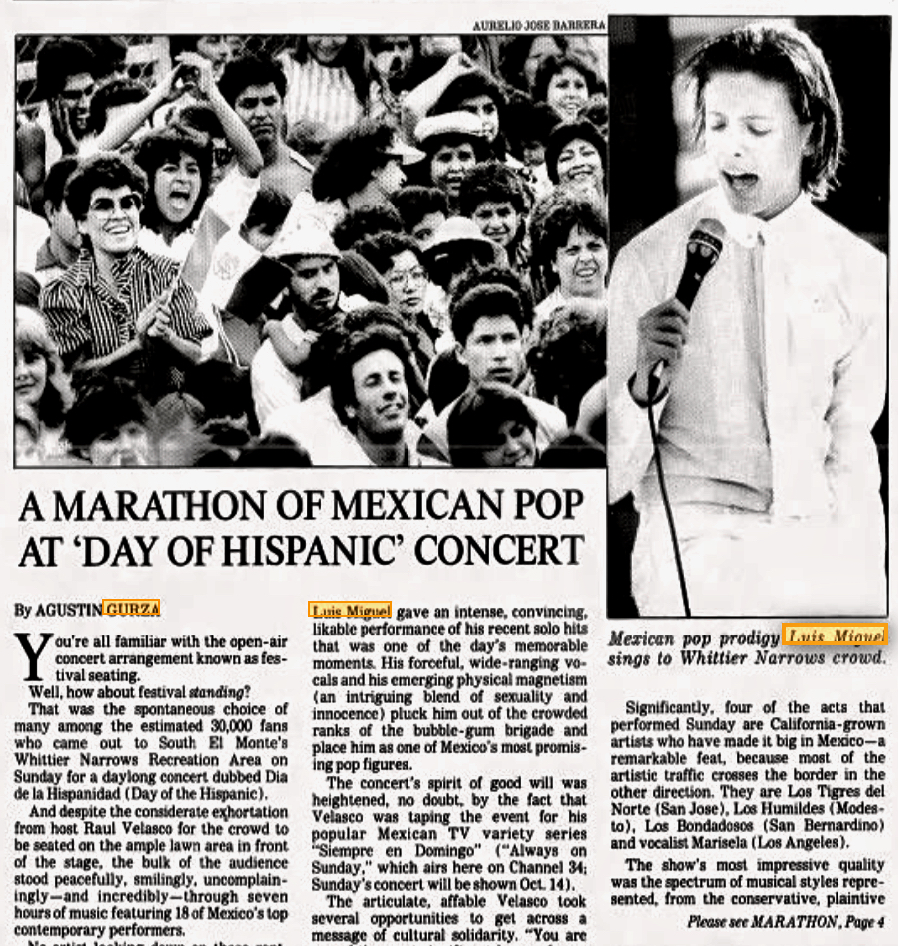

After a lull in popularity, the bolero saw a major resurgence during the 1990s with a series of four top-selling albums by pop vocalist Luis Miguel of Mexico. Although the titles are redundant, they reflect the essential subject of all boleros: Romance (1991), Segundo Romance (1994), Romances (1997), and Mis Romances (2001). Recorded mostly in Los Angeles for Warner Music’s domestic Latin labels, the LPs feature a total of 48 boleros from the 1930s through the 1980s, arranged by Argentine composer and conductor Bebu Silvetti. Singer-songwriter Armando Manzanero served as co-producer on the first three releases, but Luis Miguel flew solo on the last one, which proved the least commercially successful of the four.

After 10 years, apparently, fans had their fill of recycled boleros.

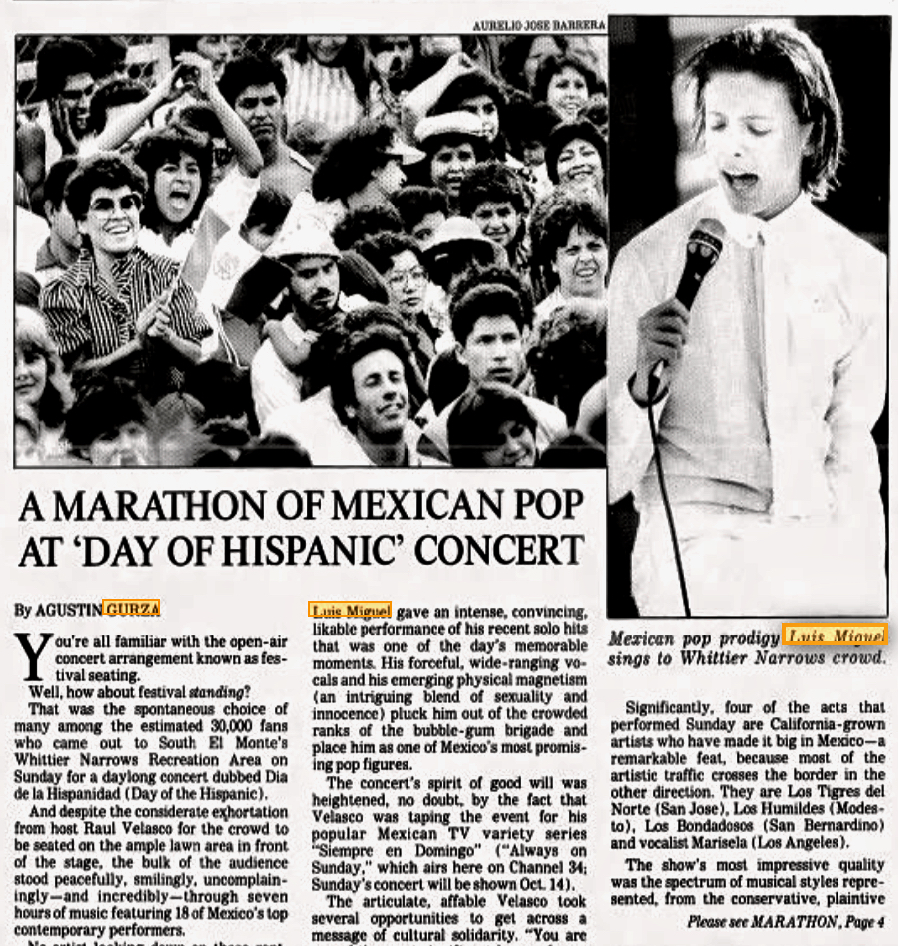

I was in Mexico in the early 1990s, and Luis Miguel love songs were everywhere. They could be heard on buses, in restaurants, and on city sidewalks wafting from storefronts. I was never a fan of those albums, although I acknowledged the former child star’s impressive vocal talents in my Los Angeles Times review of one of his earliest performances here in 1984, when he was just 14. The teenager had mucho charisma.

The problem with his bolero albums is over-production. The arrangements are fussy, intrusive, with too many frills and instrumental clutter. The songs are polished to a lifeless sheen, driven more by corporate calculations than creative corazón. It’s the same problem with the original Let It Be album by The Beatles, with Phil Spector’s suffocating wall of sound, later removed in the pared-down version, Let It Be Naked. A similar, simpler remix on the Luis Miguel records would help highlight the beauty of his vocals and the songs, but censors may object to a reissued Romance Desnudo.

On the positive side, the massive success of Luis Miguel’s Romance series underscored the enduring appeal of the bolero. To this day, those songs are finding new generations of fans through fresh interpretations by young artists, such as Mexico’s Natalia Lafourcade and L.A.-based Guatemalan singer Gaby Moreno.

How does a genre that’s more than 100 years old continue to inspire fans who weren’t even born when they were written, especially today when pop music is so disposable? I grew up in the United States, but I am somehow steeped in the bolero tradition, from my native Mexico to Cuba and elsewhere. I know those songs as thoroughly as I know the Beatles repertoire from my teenage years in San Jose.

My love of the bolero has lasted a lifetime. In the rest of this three-part exploration of the genre, I have selected songs from three phases of my life – my childhood, my college years, and mature adulthood. My goal is to show how I learned these songs from afar, made them part of my personal soundtrack, even played them at my wedding.

The bolero, like love itself, is eternal.

Songs My Parents Taught Me

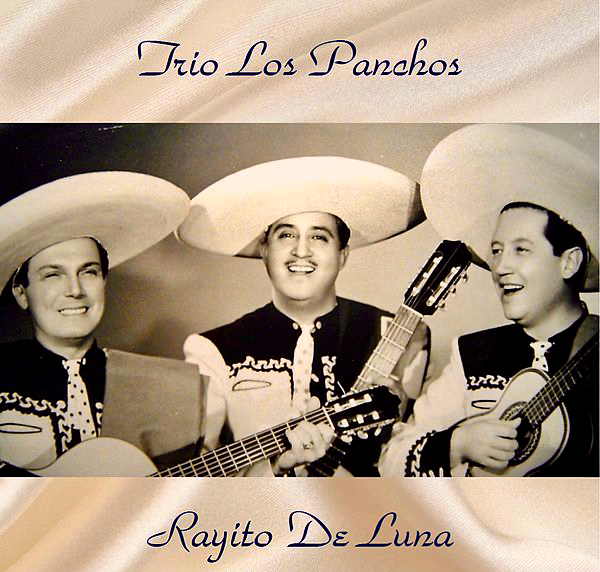

“Rayito de Luna” by Trio Los Panchos

As a kid, I would take my father’s albums by Los Panchos, squeeze behind his stereo console, and immerse myself in the romantic music of the 1940s and ’50s. I tried to hide because my older siblings would make fun of me for liking traditional music they considered corny in the early rock era. For some reason, I was the only one of eight siblings that developed a life-long obsession with the music my parents played at family gatherings where relatives were always sharing memories the music evoked. My dad’s large record collection became a portal to the Mexico I only knew through them.

As a kid, I would take my father’s albums by Los Panchos, squeeze behind his stereo console, and immerse myself in the romantic music of the 1940s and ’50s. I tried to hide because my older siblings would make fun of me for liking traditional music they considered corny in the early rock era. For some reason, I was the only one of eight siblings that developed a life-long obsession with the music my parents played at family gatherings where relatives were always sharing memories the music evoked. My dad’s large record collection became a portal to the Mexico I only knew through them.

Los Panchos, who have 473 tracks in the Frontera Collection, recorded dozens of boleros. The blissful “Rayito de Luna,” written by founding member Chucho Navarro, is the first one I remember. I was entranced by the three-part harmonies and the unabashed romanticism, with the image of love shining through the woman’s eyes as a little ray of moonlight, to rescue the swooning man’s errant life and lighten his path. The trio’s boleros were often accompanied by light percussion, with the pleasant clip-clop of a bongo or sharp crack of a timbal adding savory accents to the rhythmic breaks. The percussive pops struck a chord in me that perhaps primed my later interest in Afro-Caribbean music of all types.

For strikingly different interpretations of this song, check out the norteño rendition by Flaco Jimenez and the lush orchestral arrangement by Ray Vasquez with the orchestra of George Hernandez.

Other memorable boleros from the Panchos catalog:

The hopeful and uplifting “Flor de Azalea” by the Mexican songwriting team of Zacarías Gómez and Manuel Esperón; the pure love of “Contigo” by Mexico’s Claudio Estrada; the dark despondency of “Sin Ti” by Cuba’s Osvaldo Farrés; the hopeless loss of “Un Siglo de Ausencia” by the trio’s Alfredo Gil, another founding member; and the resigned goodbye of “Una Copa Mas” also by Navarro.

“Noche de Ronda” by Agustín Lara

Agustín Lara (1897-1970) is perhaps Mexico’s premiere composer of boleros, author of many songs that today are considered international standards. He embodied the bolero’s bohemian, desultory side. He was thin, almost skeletal, with a craggy, weathered face, a cigarette hanging from his lips, seated sideways at the piano, lamenting the latest of his lost loves. He was famously married to the glamorous María Felix but he often wrote of his illicit encounters with women of the night who broke his heart. In “Noche de Ronda,” you can picture him, alone, staring out the window onto his native Veracruz, begging the night to tell him where his lover has gone. The title is sometimes translated as “night rounds,” but the Spanish word has a deeper cultural meaning. A “ronda” can suggest barhopping but it also evokes a night of romantic serenading. Yet for Lara, nothing good can come of them: Que las rondas no son buenas/Que hacen daño/Que dan penas/Que se acaba/Por llorar.

The song would put a nostalgic, far-away look on my mother’s face. It clearly moved her, though she was extremely proper and Catholic. For her, I think, part of the appeal was her sympathy for the suffering Lara, nicknamed El Flaco de Oro. The artist’s wounded soul comes through on this recording, with his fragile piano introduction and his voice drenched in loneliness and yearning. There have been scores of covers, but nobody conveys the song’s deep heartache like Lara himself.

The Frontera database has a total of 34 editions of the song, including 11 on 78-rpm discs. Among them are two versions by the iconic Texas singer Lydia Mendoza, a haunting interpretation with her guitar on the Azteca label, and a Bluebird recording featuring her sister Maria Mendoza playing mandolin.

Also included is Agustín Lara’s own rendition – con su piano y sus ritmos – re-issued by RCA Victor on an LP entitled Rosa, featuring many of his most beloved compositions.

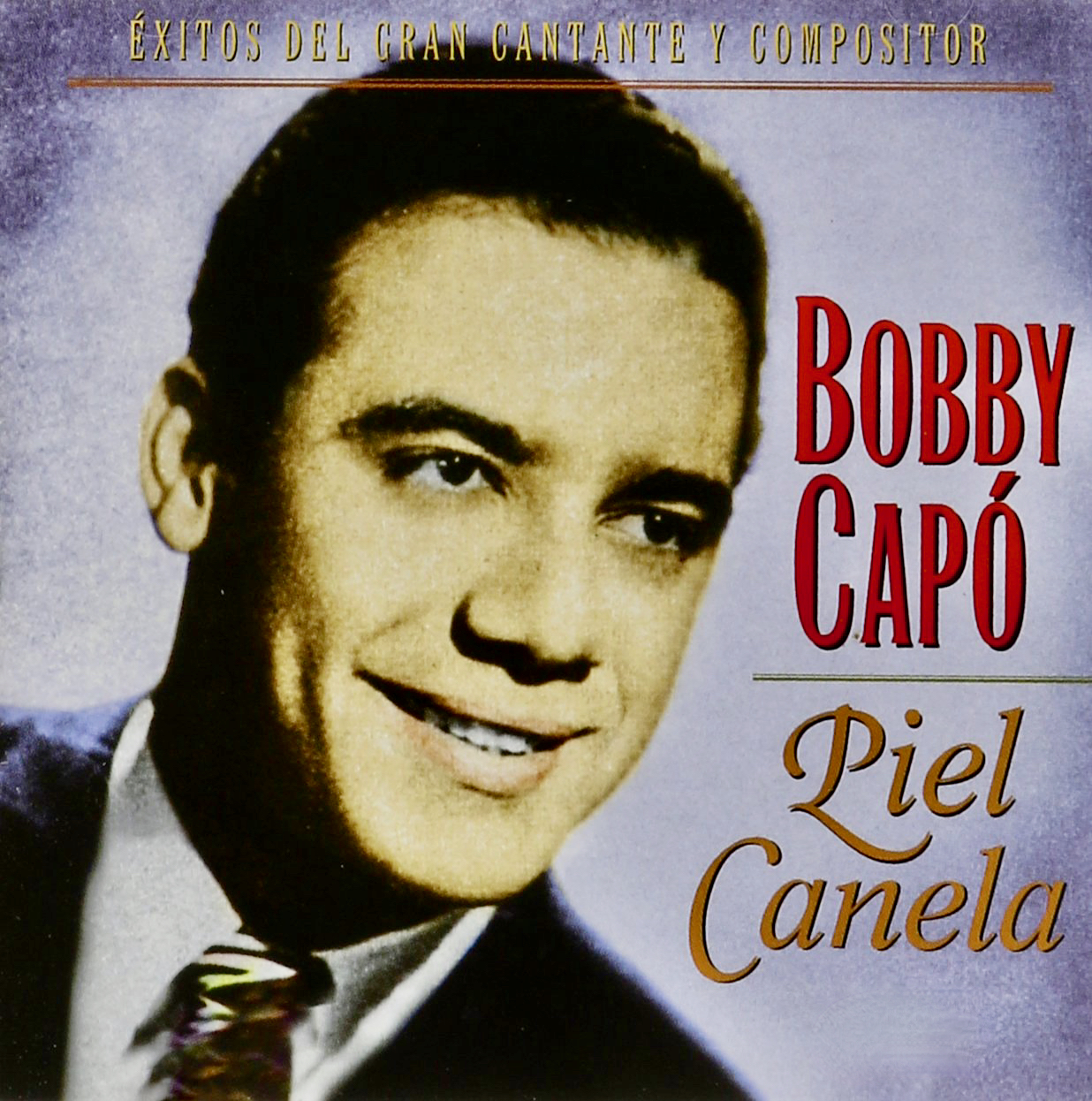

“Piel Canela” by Pedro Vargas

Pedro Vargas, the refined Mexican crooner with a honeyed tenor, performed a historic concert at Carnegie Hall in 1964, recorded live by RCA and released originally as a three-box set. My parents played, and displayed, that album whenever they had a chance. But my mother and father shared more than just musical appreciation. They shared a palpable pride in knowing one of their favorite artists was showcased on a prestigious New York stage. It was a big deal to them because the singer’s success, and the quality of his cosmopolitan music, counteracted the cheap stereotypes of Mexicans as uncouth and uncivilized, which they resented.

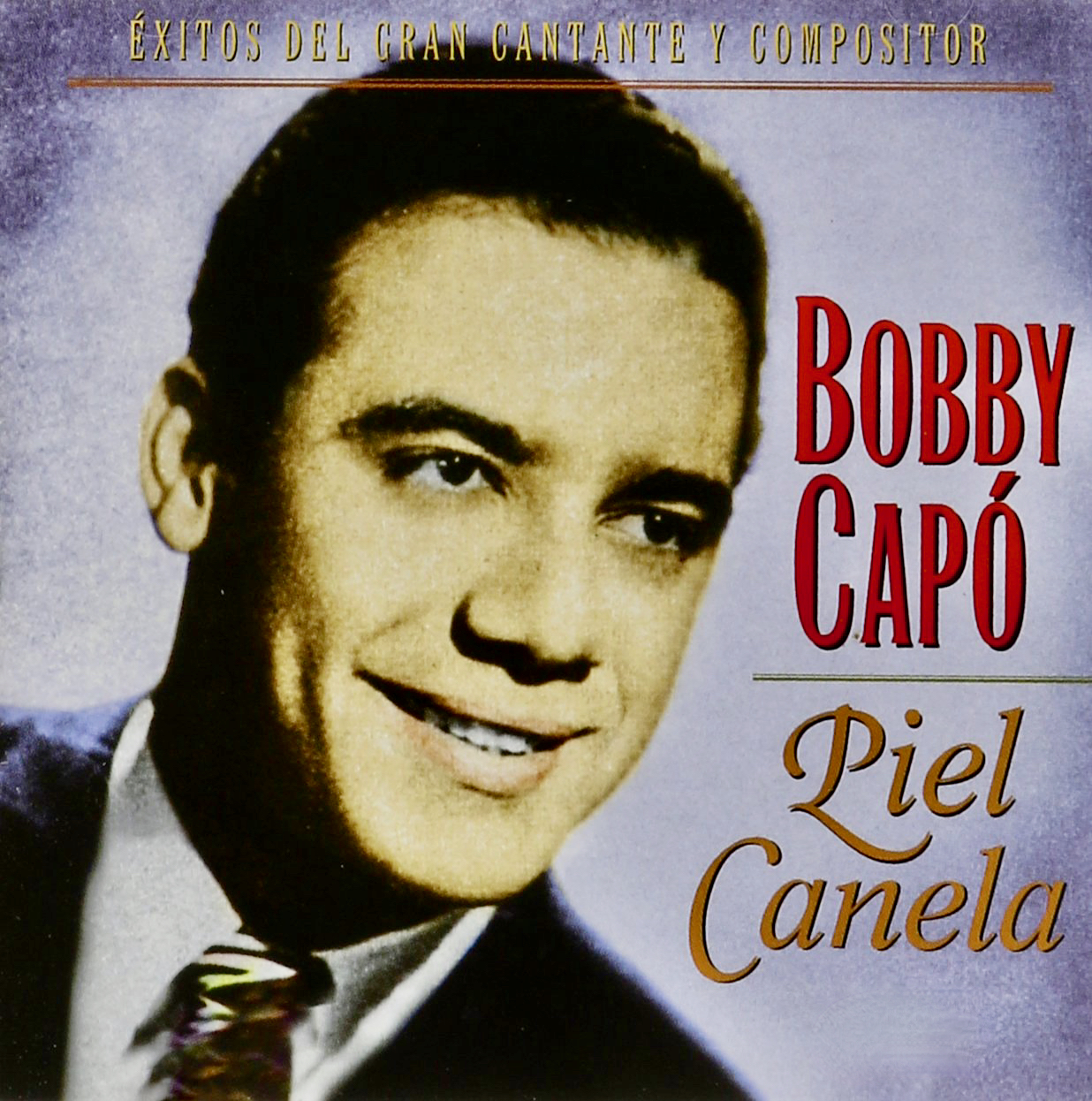

“Piel Canela” (Cinnamon Skin) is one of several famous boleros he sang during that concert, backed by the 26‐piece orchestra of Jesus “Chucho” Zarzosa and Mariachi Los Camperos from Los Angeles. This is an upbeat love song with lush poetic imagery, written by Bobby Capó, the famed singer-songwriter from Puerto Rico. The essential concept may be cliché: He loves her more than the sky and the sea, more than rainbows and flowers. But the way he expresses it is enchanting because he can live without Nature’s unfathomable beauty, but not without hers.

Que se quede el infinito sin estrellas

O que pierda el ancho mar su inmensidad

Pero el negro de tus ojos que no muera

Y el canela de tu piel se quede igual.

The bridge diverges into a simple, repetitive, almost childlike refrain:

Me importas tú, y tú, y tú

Y solamente tú, y tú, y tú

Me importas tú, mi cielo, tú, y tú, y tú

Y nadie mas que tú.

The song then returns with an irresistible swell to the song’s soaring lyricism and lovely melody. Here, the composer underscores the color of his lover’s features (Ojos negros, piel canela, Que me llegan a desesperar), affirming it as an anthem to mestizo beauty.

The song’s tropical feel is no doubt due to Capó’s Caribbean roots, showcased on this Seeco 78 in the archive, backed by Cuba’s Sonora Matancera. The Frontera Collection also features other notable 78-rpm renditions, including one by Trío Los Panchos, an oddly arranged version by Nuyorican bandleader and crooner Tito Rodriguez on Tico Records, and a bouncy take by the celebrated Los Madrugadores del Valle with accordion and a polka-like feel. There’s also a more recent, upbeat version by Pedro Vargas on an RCA Victor LP, this time with the strings and horns of the orchestra, led by Mexico’s renowned bandleader Mario Ruiz Armengol, who thankfully sublimated the instruments to Vargas’s rich vocals.

“Cenizas” by Toña La Negra

My father loved Toña La Negra, an elegant Afro-Mexican singer also from Veracruz, thus nicknamed La Sensación Jarocha. Dr. Gurza wasn’t as articulate as my mother about his musical tastes, but he had many of the artist’s records on RCA. Born María Antonia del Carmen Peregrino Alvarez, she was a leading interpreter of Agustín Lara, with a warm, intimate vocal style that ranged from a throaty tenor to a pure, high-pitched warble. Her cabaret cachet is well-suited to this song about a woman’s love left in ashes, hence the title. She addresses the man who broke her heart and sings like she’s talking only to him. The cad has come back after suffering his own heartbreak (desventura), but she’s not resentful because, as she explains, there is no rancor left when love has died. (Has de saber, que en un cariño muerto, no existe el rencor.) Then she delivers the line that, if words could kill, would be the death of any hope he could have had of reconciling:

My father loved Toña La Negra, an elegant Afro-Mexican singer also from Veracruz, thus nicknamed La Sensación Jarocha. Dr. Gurza wasn’t as articulate as my mother about his musical tastes, but he had many of the artist’s records on RCA. Born María Antonia del Carmen Peregrino Alvarez, she was a leading interpreter of Agustín Lara, with a warm, intimate vocal style that ranged from a throaty tenor to a pure, high-pitched warble. Her cabaret cachet is well-suited to this song about a woman’s love left in ashes, hence the title. She addresses the man who broke her heart and sings like she’s talking only to him. The cad has come back after suffering his own heartbreak (desventura), but she’s not resentful because, as she explains, there is no rancor left when love has died. (Has de saber, que en un cariño muerto, no existe el rencor.) Then she delivers the line that, if words could kill, would be the death of any hope he could have had of reconciling:

Y si pretendes remover las ruinas

Que tú mismo hiciste,

Sólo cenizas hallarás

De todo lo que fue mi amor

Though the anger may have died with the relationship, the song still conveys a sense of enormous sadness and loss. It was written by Manuel (Wello) Rivas Ávila, from Mérida, Yucatan, also on the Gulf of Mexico. Rivas, born 1913, is part of a stellar generation of romantic Mexican artists, including fellow composers Guty Cárdenas (1905), Gabriel Ruiz (1908) and Consuelo Velázquez (1916) – who wrote the internationally famous “Bésame Mucho.” The era’s singers include Toña La Negra (1912), Pedro Vargas (1906), and all three founding members of Los Panchos: Navarro (1913), Gil (1915), and Avilés (1914).

My father, born in 1918, was their contemporary and biggest fan.

There’s another famous version of the song, by Mexican superstar Javier Solis, known as El Rey del Bolero Ranchero. The Frontera Collection has 16 recordings of the song, including four by Toña La Negra on three different labels. Other notable versions include a catchy mid-tempo rendition by Salomon Prado with a conjunto norteño, a tender mariachi interpretation by Chelo with expertly tailored harmonies, and an affected, overly adorned trio version by Los Tres Ases which can be heard on this YouTube video.

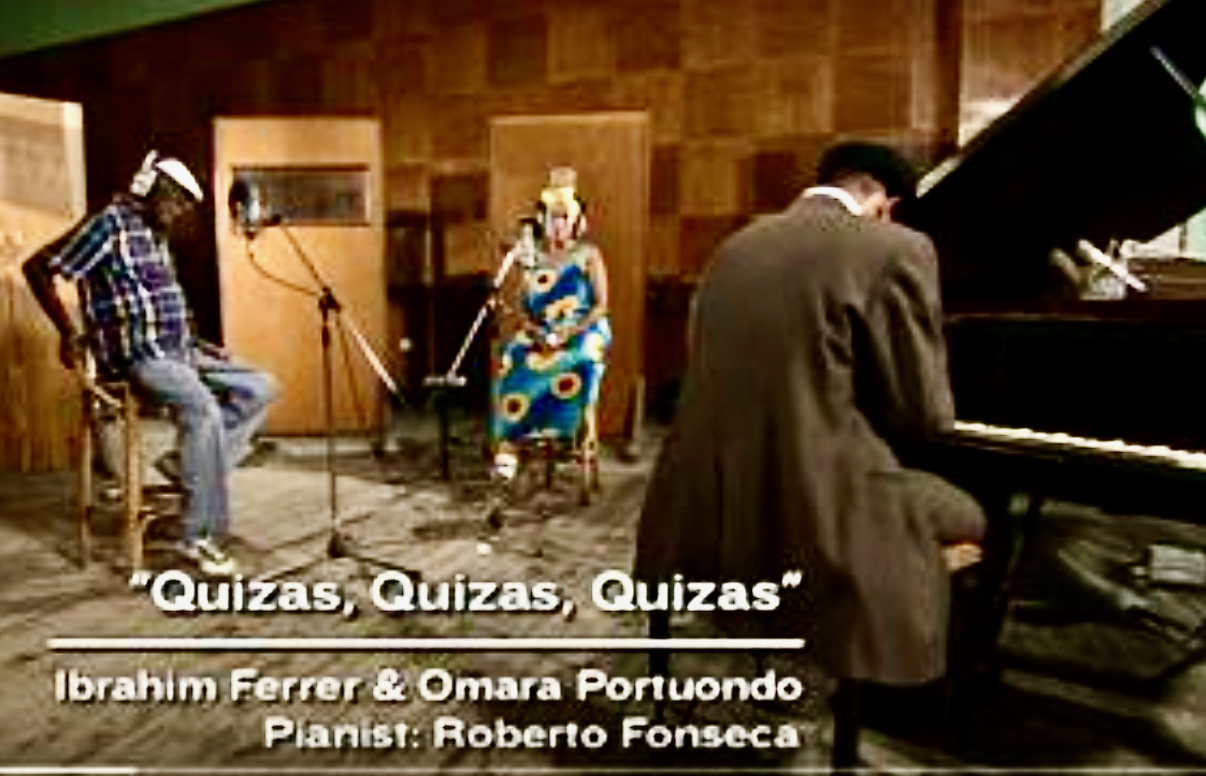

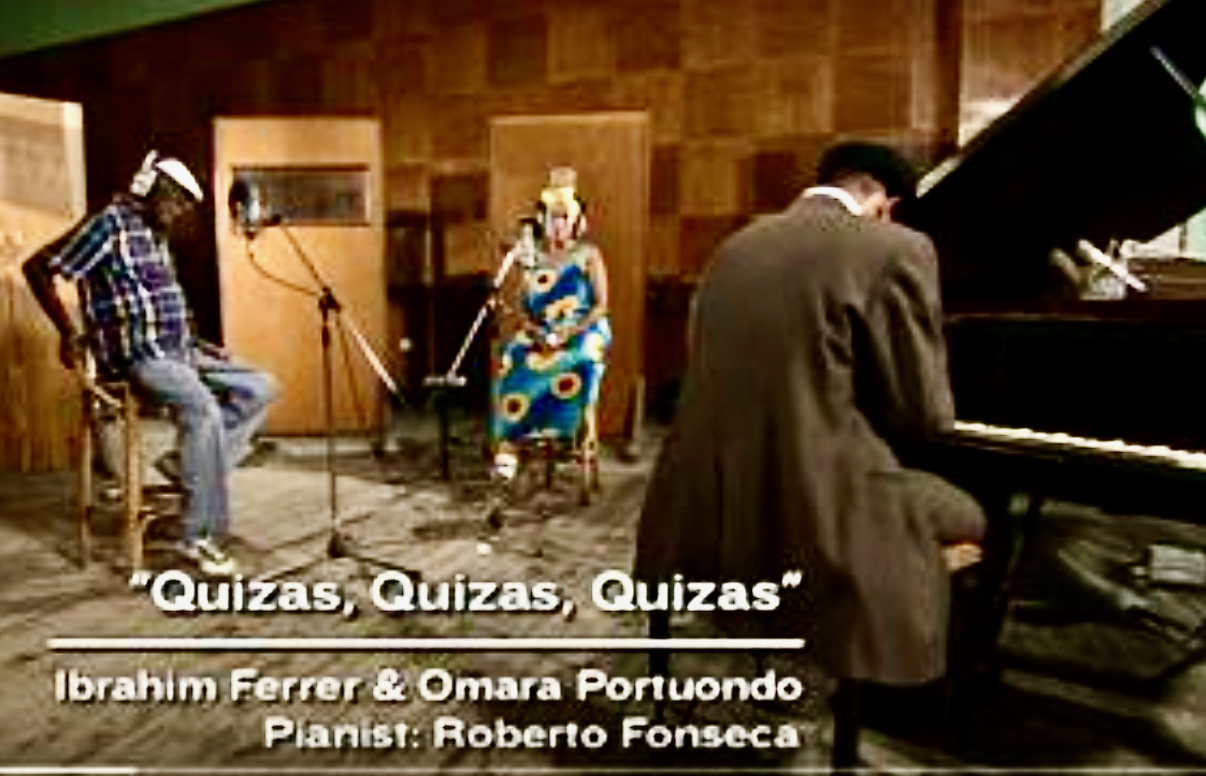

“Quizás, Quizás, Quizás” by Omara Portuondo and Ibrahim Ferrer

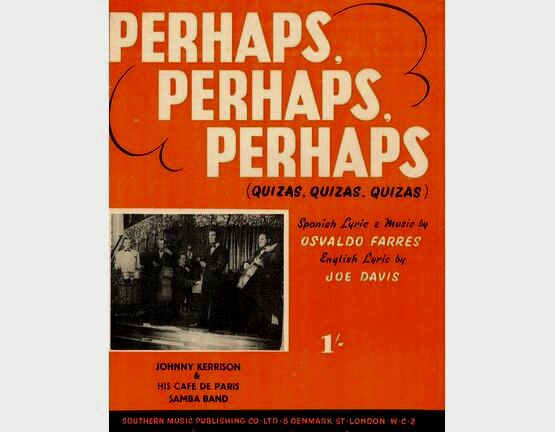

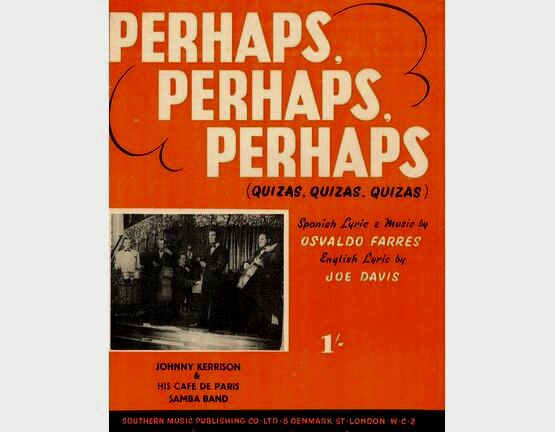

This is certainly one of the most widely recognized boleros of all time, thanks to the multiple renditions of the song in Spanish and English. The first recording of the bolero is credited to Trio Durango, issued December 1947 on Peerless (No. 2417), then Mexico’s leading independent record company. The Peerless label uses a common variation of the title, “Quiza, quiza,” with no “s,” no accent, and no triple “quiza.”

The first English version was recorded in 1948 by Cuban-born actor and musician Desi Arnaz for RCA Victor, featuring an intricate, cosmopolitan arrangement. Literally translated by Joe Davis as “Perhaps, Perhaps, Perhaps,” the song is actually performed bilingually by Arnaz, with alternating verses in English and Spanish. The side-by-side verses underscore how closely the translation hews to the original in sentiment and meaning, albeit less artfully.

Many other major stars followed, with recordings in both languages: Bobby Capó (1952), Xavier Cugat (1952), Nat King Cole (1958), The Ames Brothers (1958), Ben E. King (1961), Doris Day (1964), Connie Francis (1960), Trio Los Panchos (1960), Sarita Montiel (1963), Trini Lopez (1964), Celia Cruz (1964), Chucho Valdés & Irakere (1996), Cake (1996), Buena Vista Social Club (Live 2008), Andrea Bocelli with Jennifer Lopez (2008), Natalie Cole (2008), Pussycat Dolls (2008), Pink Martini (2013), and Oscar D'León (2014).

Many other major stars followed, with recordings in both languages: Bobby Capó (1952), Xavier Cugat (1952), Nat King Cole (1958), The Ames Brothers (1958), Ben E. King (1961), Doris Day (1964), Connie Francis (1960), Trio Los Panchos (1960), Sarita Montiel (1963), Trini Lopez (1964), Celia Cruz (1964), Chucho Valdés & Irakere (1996), Cake (1996), Buena Vista Social Club (Live 2008), Andrea Bocelli with Jennifer Lopez (2008), Natalie Cole (2008), Pussycat Dolls (2008), Pink Martini (2013), and Oscar D'León (2014).

The most recent version I could find is also among the quirkiest - a fanciful, jazzy version by Montana’s versatile dance band, The Big Sky Mudflaps, known to play with a washtub bass.

The website SecondHandSongs lists a total of 215 versions in six languages, including Finish (“Kenties, kenties, kenties), French (“Qui sait, qui sait, qui sait”), German (“Wer weiß? Wer weiß? Wer weiß?”), Italian (“Chissà, chissà, chissà”), and Japanese (キサス、キサス).

Written by celebrated Cuban composer Osvaldo Farrés (1903-1985), the song’s initial languid pace and melancholic tone is interrupted by the staccato repetition of the three-word title, giving way to an energetic chorus with a lilting sway. The changes in mood and movement lends a touch of playfulness to the song, leading to pop-ditty renditions that miss the point: the song is about a forlorn suitor left dangling on a string due to elusive love, perpetually unrequited but always dangled as a possibility – perhaps!

I prefer the version featured above by two veteran Cuban vocalists, Omara Portuondo and Ibrahim Ferrer, veterans of Cuba’s bolero traditions. Their performance is pared down to fundamentals: harmonizing voices backed by the solo piano of Cuba’s brilliant Roberto Fonseca. There is no playfulness in this performance. It is all heart and soul. By stripping away any excess, they lay bare the key ingredients of every great song: the lyrics and the melody. And the singers perfectly express the emotional essence of this touching bolero: longing for a cherished loved one who will always remain just out of reach.

I prefer the version featured above by two veteran Cuban vocalists, Omara Portuondo and Ibrahim Ferrer, veterans of Cuba’s bolero traditions. Their performance is pared down to fundamentals: harmonizing voices backed by the solo piano of Cuba’s brilliant Roberto Fonseca. There is no playfulness in this performance. It is all heart and soul. By stripping away any excess, they lay bare the key ingredients of every great song: the lyrics and the melody. And the singers perfectly express the emotional essence of this touching bolero: longing for a cherished loved one who will always remain just out of reach.

American listeners will recognize this elderly duo as members of the famed Buena Vista Social Club, the 1997 group whose albums sparked a worldwide boom in traditional Cuban music.

More about the boleros of Buena Vista in Part 3 of this series.

̶Agustín Gurza

Also in this series:

Blog Category

Tags

Images