the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center,

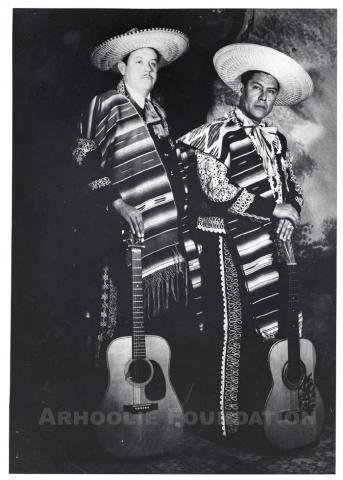

the Arhoolie Foundation,

and the UCLA Digital Library

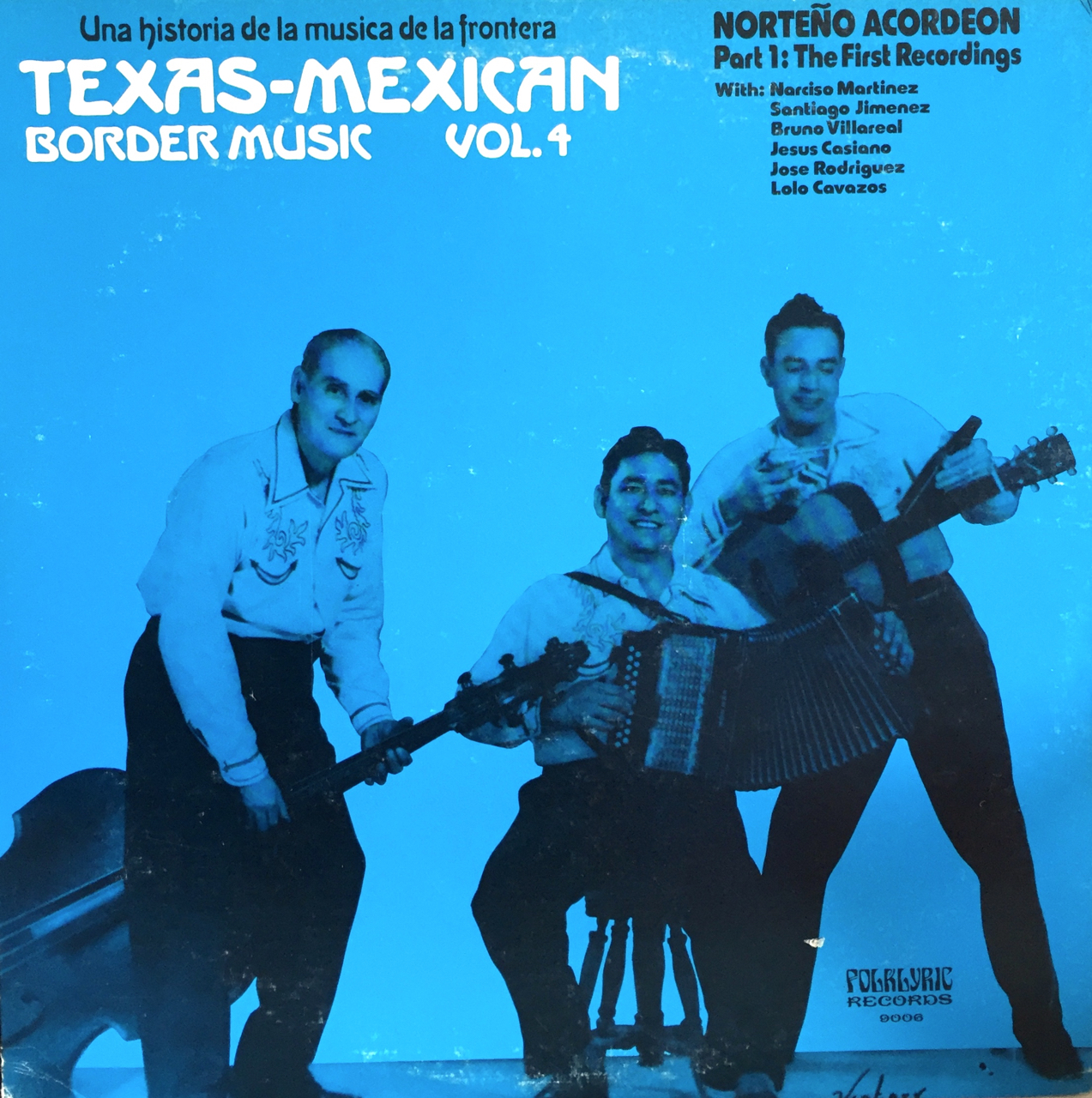

The first accordion was built in 1822 by Friedrich Buschmann (1805 –1864), a German musical instrument-maker also credited with inventing the harmonica. He called it a Ziehharmonika (zieh in German means pull). However it was Cyrill Damian who in 1829 in Vienna, Austria, began to mass-produce and adopt the name accordion for these instruments. (In Spanish, the name of the instrument is spelled acordeón.)

The first accordion was built in 1822 by Friedrich Buschmann (1805 –1864), a German musical instrument-maker also credited with inventing the harmonica. He called it a Ziehharmonika (zieh in German means pull). However it was Cyrill Damian who in 1829 in Vienna, Austria, began to mass-produce and adopt the name accordion for these instruments. (In Spanish, the name of the instrument is spelled acordeón.)

I’ve been listening to Latin music all my life, especially Mexican music. So it’s not every day that I discover a whole new genre, with its own special history. But that’s just what happened recently while I was researching disaster songs in the Frontera Collection. The genre I discovered completely by chance is called La Chilena. And though it’s named for the country in South America, the song and dance style actually come from the coastal area of southern Mexico known as La Costa Chica, along the states of Guerrero and Oaxaca.

I’ve been listening to Latin music all my life, especially Mexican music. So it’s not every day that I discover a whole new genre, with its own special history. But that’s just what happened recently while I was researching disaster songs in the Frontera Collection. The genre I discovered completely by chance is called La Chilena. And though it’s named for the country in South America, the song and dance style actually come from the coastal area of southern Mexico known as La Costa Chica, along the states of Guerrero and Oaxaca.

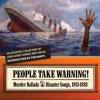

In my last blog, I looked at the history of disaster songs and cited some examples from the Frontera Collection. But, as it turns out, one of the most original and provocative songs of this genre is about a disaster that never happened.

Most people know that the worst natural disaster in California history was the San Francisco Earthquake of 1906. But which calamity ranks No. 2? That happened in Los Angeles in 1932: a catastrophic dam break that killed 600 people, wiped out neighborhoods all the way to the ocean near Ventura, and ended the career of William Mulholland, the famed engineer who had designed the water system for the new metropolis blooming in the Southern California desert.

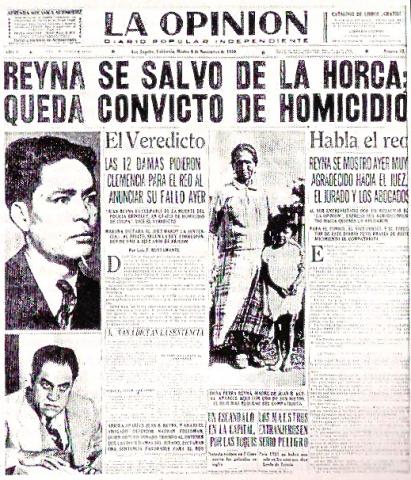

Recordings are more than just entertainment. They are windows on a culture. In the voice of artists, songs give us a glimpse into what people think and feel in a particular time and place. We hear it in Mississippi Delta blues, the Argentine tango, San Francisco ’60s rock, and a specialty of this archive, the Mexican-American corrido of the early 20th century in the Southwest United States.

Recordings are more than just entertainment. They are windows on a culture. In the voice of artists, songs give us a glimpse into what people think and feel in a particular time and place. We hear it in Mississippi Delta blues, the Argentine tango, San Francisco ’60s rock, and a specialty of this archive, the Mexican-American corrido of the early 20th century in the Southwest United States.

It’s not often that so-called millennials lead us back to music from the past century, especially Latin music. Showbiz today is all about being young, fresh, and new.

It’s not often that so-called millennials lead us back to music from the past century, especially Latin music. Showbiz today is all about being young, fresh, and new.

Singer Eva Garza launched her singing career as a teenager in San Antonio, Texas, and emerged as one of the few Mexican-American artists to gain international acclaim throughout the Americas. An accomplished and seductive interpreter of the romantic bolero, she collaborated during the 1940s and ’50s with top figures in the field, including Mexico’s Agustin Lara and Cuba’s Isolina Carrillo.

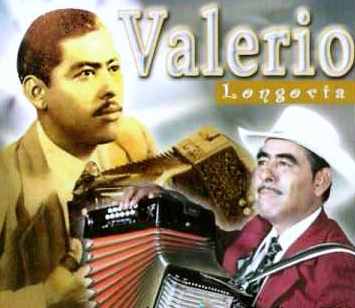

Singer Eva Garza launched her singing career as a teenager in San Antonio, Texas, and emerged as one of the few Mexican-American artists to gain international acclaim throughout the Americas. An accomplished and seductive interpreter of the romantic bolero, she collaborated during the 1940s and ’50s with top figures in the field, including Mexico’s Agustin Lara and Cuba’s Isolina Carrillo. Valerio Longoria is considered one of the most innovative conjunto musicians who shaped the music’s classic period in the post-World War II era, a group considered “la nueva generación,” the new generation. The son of migrant farmworkers, he is credited with a number of firsts in the Tejano genre during a career that spanned more than 60 years.

Valerio Longoria is considered one of the most innovative conjunto musicians who shaped the music’s classic period in the post-World War II era, a group considered “la nueva generación,” the new generation. The son of migrant farmworkers, he is credited with a number of firsts in the Tejano genre during a career that spanned more than 60 years.

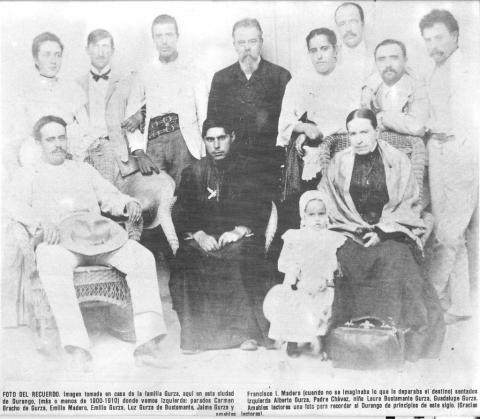

This past February 22 marked the 103rd anniversary of the assassination of Mexico’s first revolutionary president, Francisco Madero. And like other historic events, Madero’s tragic deposition and death are documented through historic reenactments that were recorded to give a pre-television public the sense of personally witnessing events. Today, we can listen to those recordings on our computers, thanks to digital copies of those 78-rpm discs found in the Frontera Collection.

This past February 22 marked the 103rd anniversary of the assassination of Mexico’s first revolutionary president, Francisco Madero. And like other historic events, Madero’s tragic deposition and death are documented through historic reenactments that were recorded to give a pre-television public the sense of personally witnessing events. Today, we can listen to those recordings on our computers, thanks to digital copies of those 78-rpm discs found in the Frontera Collection. One of the most important contributions of the Frontera Collection is the documentation of Mexican-American music, a cultural legacy that may have otherwise been lost or overlooked. Both as a writer and a record collector, I am often dismayed at how little information is available on artists and their recordings, not just Mexican Americans but Latino musicians in general.

One of the most important contributions of the Frontera Collection is the documentation of Mexican-American music, a cultural legacy that may have otherwise been lost or overlooked. Both as a writer and a record collector, I am often dismayed at how little information is available on artists and their recordings, not just Mexican Americans but Latino musicians in general.

Recently, an observant music fan noticed an error on this site and wrote to tell us about it. His concern is related to one of the most famous and recognizable compositions in the Latin American songbook, entitled “Malagueña” or “La Malagueña.”

Recently, an observant music fan noticed an error on this site and wrote to tell us about it. His concern is related to one of the most famous and recognizable compositions in the Latin American songbook, entitled “Malagueña” or “La Malagueña.”  In rock music, fans are often on a first-name basis with band members, like John, Paul, George, and Ringo. In salsa during the boom of the 1970s, fans started demanding musician credits on every album because, as with jazz, they followed the sidemen sometimes as much as the featured front.

In rock music, fans are often on a first-name basis with band members, like John, Paul, George, and Ringo. In salsa during the boom of the 1970s, fans started demanding musician credits on every album because, as with jazz, they followed the sidemen sometimes as much as the featured front.  Judging from the title alone, you’d think “Betty Ford” by Mariachi Continental De Miguel Diaz was about a former First Lady. The song is an instrumental, so there are no lyrics telling us a story. The genre, however, gives us a clue to its subject. It’s listed in the Frontera Collection as a pasodoble, the theatrical but graceful style of song typically played at bullfights, especially during the entrance of the matadors.

Judging from the title alone, you’d think “Betty Ford” by Mariachi Continental De Miguel Diaz was about a former First Lady. The song is an instrumental, so there are no lyrics telling us a story. The genre, however, gives us a clue to its subject. It’s listed in the Frontera Collection as a pasodoble, the theatrical but graceful style of song typically played at bullfights, especially during the entrance of the matadors.  Library archives can seem like dusty old places, even in today’s digital world. It’s usually the job of historians and ethnomusicologists to rummage around the artifacts of a bygone era, like the many 78-rpm records from the first half of the last century that can be found in the Frontera Collection. Researchers must find a way to help us understand those pre-modern recordings and the social context in which they were made.

Library archives can seem like dusty old places, even in today’s digital world. It’s usually the job of historians and ethnomusicologists to rummage around the artifacts of a bygone era, like the many 78-rpm records from the first half of the last century that can be found in the Frontera Collection. Researchers must find a way to help us understand those pre-modern recordings and the social context in which they were made.  Eva Quintanar was a prolific composer, instrumentalist, singer, and musical director during the 1940s and ’50s in Los Angeles, and one of the few women to take leadership roles in the male-dominated music industry of her day. She appeared regularly with her own orchestra at renowned downtown venues, especially the Million Dollar Theatre, and gained a reputation as a first-rate accompanist for internationally known stars from Mexico, such as Pedro Infante and Pedro Vargas. She also served as director of the Taxco Records Orchestra, conducting recording sessions for local and international artists.

Eva Quintanar was a prolific composer, instrumentalist, singer, and musical director during the 1940s and ’50s in Los Angeles, and one of the few women to take leadership roles in the male-dominated music industry of her day. She appeared regularly with her own orchestra at renowned downtown venues, especially the Million Dollar Theatre, and gained a reputation as a first-rate accompanist for internationally known stars from Mexico, such as Pedro Infante and Pedro Vargas. She also served as director of the Taxco Records Orchestra, conducting recording sessions for local and international artists.

To read the full bio, go here.

A new feature, the Q&A, makes its debut on the Frontera Blog this week. First up is this informative conversation with John McGowan, the son of Eva Quintanar, a composer, pianist, and orchestra director who had a successful career in Los Angeles during the 1940s and ‘50s. (Read her Artist Biography here.) McGowan, professor emeritus of liberal studies at California State University, Dominguez Hills, has worked to preserve his mother’s legacy and collect her recordings, many contained in the Frontera Collection. Still active in her art as a centenarian, Quintanar is one of the few surviving musicians from an era that featured a particularly productive music scene within the local Mexican American community in Los Angeles. In this interview with Frontera website editor Agustín Gurza, McGowan, 70, provides personal recollections of his mother’s life and times.

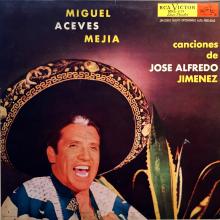

Miguel Aceves Mejía (1915-2006) is one of the leading exponents of Mexican folkloric music, with a gifted, versatile voice that made him a star throughout the Spanish-speaking world. During a career that spanned half a century, the singer and actor recorded more than 1000 songs on 90 discs and starred in over 60 films.

Miguel Aceves Mejía (1915-2006) is one of the leading exponents of Mexican folkloric music, with a gifted, versatile voice that made him a star throughout the Spanish-speaking world. During a career that spanned half a century, the singer and actor recorded more than 1000 songs on 90 discs and starred in over 60 films.

Stay informed on our latest news!